#Euparkeria

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

veryyyyy late flocking post :')

#my art#paleostream#balaur bondoc#megalania#varanus priscus#styracosaurus#euparkeria#dinosaur#paleoart

658 notes

·

View notes

Text

flocking 4/12/24 -- Balaur + V. priscus + Euparkeria + Styracosaurus

#paleostream#paleoart#dinosaurs#paleoblr#styracosaurus#balaur#megalania#euparkeria#very good selection of taxa today imo

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Flocking drawings!

Balaur just sitting around

Megalania taking a bath

Styracosaurus looking at the sunset

a pair of Euparkerias nuzzling

#paleostream#Balaur#Megalania#Styracosaurus#Euparkeria#paleoart#dinosaur#theropod#reptile#lizard#ceratopsian#Archosaur#mesozoic#cenozoic#dragon draws creatures#halfway through the Styracosaurus drawing i noticed the sunset had the lesbian colors so she is a women liker now#oh my fucking god this bitch is fucking gay good for her good for her#at least 5 people gay reacted the Euparkeria drawing on the paleostream server so i guess they have been diagnosed with gay too

422 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dinocember 2023 Week Three

#own art#dinocember#dinosaur#digital art#euparkeria#andrewsarchus#pachycephalosaurus#ubirajara#paraceratherium#estemmenosuchus#silesaurus#only two actual dinos this week#but I think the next ten are all dinos#and finally some ceratopsians

383 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paleostream 13/04/2024

here are today's #Paleostream sketches!!! today we drew Balaur bondoc, Varanus priscus (megalania), Styracosaurus, and Euparkeria

#Paleostream#paleoart#paleontology#digital art#artists on tumblr#digital artwork#palaeoart#digital illustration#sciart#id in alt text#dinosaur#bird#ceratopsian#Balaur#Balaur bondoc#Varanus#Varanus priscus#megalania#Styracosaurus#Euparkeria#palaeoblr#paleoblr

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archovember day 8! Euparkeria capensis! A very small reptile from the early Triassic! This is what I picture for reptiles right after the Permian extinction. Makes me wonder what hijinks this little fella got up to so early into the age of the dinosaurs.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

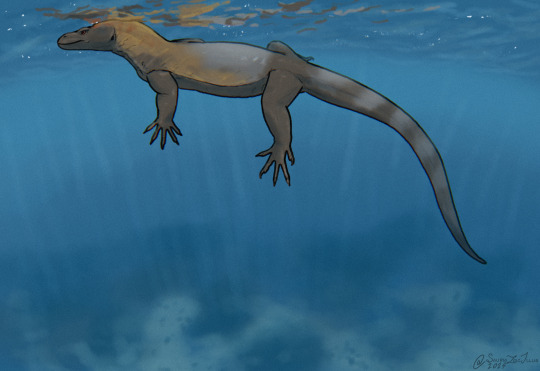

Archovember 2024 Day 8 - Euparkeria capensis

Living in Early Triassic South Africa, Euparkeria capensis is known from nearly complete skeletons, and is one of the most heavily described and discussed non-archosaur archosauriforms. It is also one of the oldest known advanced archosauriformes, and most closely related to true archosaurs, providing insight into their evolution. It had a large, boxy head, and two rows of small osteoderms down its back and tail. It had large sclerotic rings, similar to modern nocturnal reptiles, suggesting it was most active in dim light. As the Karoo Basin was at about 65 degrees south latitude in the Early Triassic, this was likely an adaptation for the long, dark Winter months. Euparkeria was fairly small for the time, and likely ate insects and carrion. Due to its hind limbs being slightly longer than its forelimbs, Euparkeria was once thought to be capable of facultative bipedalism, but a 2023 analysis shows that it was incaple of walking on its hind legs even for short periods.

Euparkeria was found in the Cynognathus Assemblage Zone of the Burgersdorp Formation. It would have lived alongside many Triassic animals, including other archosauromorphs like the even-larger-headed Erythrosuchus, and rhynchosaurs like Eohyosaurus, Howesia, and Mesosuchus. It would have also lived alongside parareptiles like Myocephalus, Teratophon, Theledectes, Thelephon, and Thelerpeton. But, for the most part, synapsids ruled the land here, and Euparkeria would have come across (and perhaps even been hunted by) the titular Cynognathus, as well as Bauria, Bolotridon, Cricodon kannemeyeri, Diademodon, Kannemeyeria, Kombuisia, Lumkuia, Microgomphodon, and Trirachodon. The water was also not always safe, as many temnospondyls also made the area their home, including Batrachosuchus, Jammerbergia, Laidleria, Microposaurus, Vanastega, and Xenotosuchus.

This art may be used for educational purposes, with credit, but please contact me first for permission before using my art. I would like to know where and how it is being used. If you don’t have something to add that was not already addressed in this caption, please do not repost this art. Thank you!

#Euparkeria capensis#Euparkeria#archosauromorphs#reptiles#Archovember#archovember2024#Dinovember#Dinovember2024#DrawDinovember#DrawDinovember2024#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#Early Triassic#or#Middle Triassic#South Africa#Cynognathus Assemblage Zone#Burgersdorp Formation

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flocking Together

Balaur bondoc

Megalania

Styracosaurus

Euparkeria

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archovember day eight! Euparkeria Capensis

little guys in a cave, i really hate this one its probably the worst one ive made. shouldnt have drawn in orange but im not redoing it

Archovember is by @/saritapaleo

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Results from the Flocking #paleostream

Balaur, Varanus priscus, Styracosaurus and Euparkeria.

497 notes

·

View notes

Note

i was rewatching the rite of spring segment from fantasia and i've got to wonder. Why Did We Draw Archaeopteryx Like That. i remember toys having that same, boomerang arm shaped pose too. it's like a monkey lizard more than a bird.

Ooh okay this is a fun one cause while it technically is an Archaeopteryx and is listed as such in the production draft, I don't think the design is based on Archaeopteryx at all!

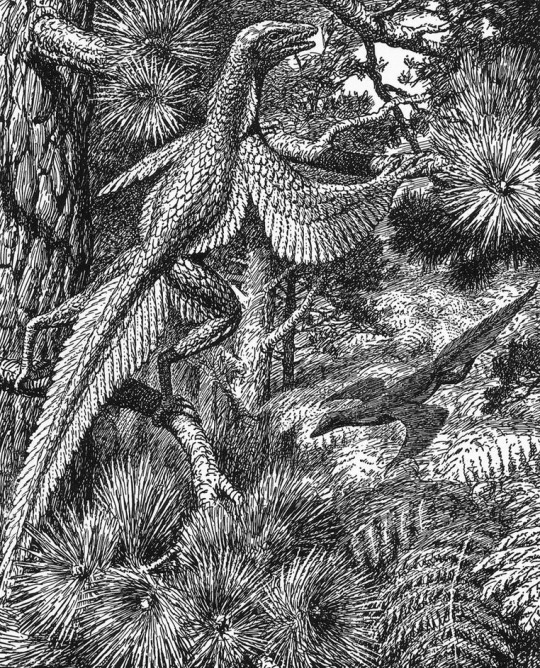

To me, this "Archaeopteryx" almost exactly resembles something else, the fascinating historical phenomenon called Proavis.

Proavis, or Tetrapteryx as some four-winged interpretations were called, was a hypothetical prehistoric creature that was proposed in the early 20th century as a best guess at what the unknown ancestor of birds could have looked like. The illustration above was drawn in 1926 by Gerhard Heilmann, a Danish artist and amateur scientist who argued that birds evolved from non-dinosaurian archosaurs like Euparkeria. In his 1916 book Vor Nuvaerende Viden om Fuglenes Afstamning and the 1926 English translation The Origin of Birds, he presented Proavis as the imagined midpoint between a scaly ground-running archosaur and Archaeopteryx, which at the time held the title of The First Bird.

Other versions of the same hypothesis, like William Beebe's Tetrapteryx above, were published and discussed around the same time, but it was Heilmann's Proavis that gained immense popularity to the point that bird evolution was considered essentially "solved" for decades. It was also painted by Zdeněk Burian, one of the Old Greats of palaeoart, which kept the concept alive in dinosaur books for decades as well.

Of course further study has shown this hypothesis to be incorrect and that birds are instead members of Dinosauria (and honestly Heilmann either missed or ignored a lot of evidence for a dinosaurian origin of birds even in the 1910s), but the Proavis to me remains a beautiful and fascinating concept that represents scientists and artists striving to understand the prehistoric world and the passage of evolution, much like we still do today!

And of course, its popularity in the early 20th century put it at the perfect time for Fantasia's artists to take... let's say heavy inspiration from Heilmann's imaginary Proavis when depicting a creature that was intended to be Archaeopteryx the whole time! The pattern of feathers matches up almost exactly, although the larger leg wings might have been inspired by Beebe's Tetrapteryx as well:

So to get back to your original question that led to this whole deep dive, artists didn't actually Draw Archaeopteryx Like That except when they were mistakenly drawing something that wasn't Archaeopteryx at all! If you want to read more about the Proavis and Tetrapteryx I recommend this Tetrapod Zoology blog post by Darren Naish, he does into more depth about the history of the concept and some of the unusual evolutionary ideas that Heilmann used to arrive at this weird and cool imaginary creature!

801 notes

·

View notes

Text

Doodles from today's flocking paleostream featuring Balaur, Varanus priscus, Styracosaurus, and Euparkeria.

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

picking these 10 was very difficult there are too many triassic weirdos and I'm not even touching the sea right now

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last Day of Tier 1!

Euparkeria is an archosauromorph close to the beginnings of archosauria as a whole. It is from the earlt Triassic some 15 to 20 million years before dinosaurs.

Schleromochlus is a pterosauromorph, an archosaur more closelynrelated to pterosaurs than dinosaurs. A recent study feom 2020 suggested it hopped around like a frog.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life in the Middle Triassic

(first row: Euparkeria, Tanystropheus; second row: Nothosaurus, Nyasasaurus; third row: Thalattosaurus (top), Mastodonsaurus (bottom), Cynognathus, Longisquama; fourth row: Shringasaurus, Sharovipteryx, Placodus)

Art by:

Tanystropheus, Nyasasaurus - Mark Witton

Thalattosaurus - Nobu Tamura

Nothosaurus - Johnson Mortimer

Mastodonsaurus - Vladislav Egorov

Sharovipteryx, Longisquama - Julio Lacerda

Shringasaurus - Ntvtiko

Cynognathus - Gabriel Ugueto

Euparkeria - Taenadoman

Placodus - Sergey Krasovsky

The Triassic is a fantastic time if you’re interested in weird creatures and it’s a shame that it often gets overlooked in favor of the more dinosaur-rich Jurassic and Cretaceous. The main reason for the abundance of Triassic weirdos is that the time period was bookended on both sides by mass extinctions: The end Permian mass extinction had just left the planet empty, with lots of opportunities for evolution to go crazy as the the few survivors refilled niches. At the end of the Triassic however (Spoiler alert), another mass extinction wiped out most of the newly established forms, which is why they look so foreign and strange to us - bizarre anomalies that only existed for a brief period of time and didn‘t leave any successors to help us understand them better.

One of those weirdos is leg-winged Sharovipteryx. Because yes, while every other vertebrate on the planet decided that arms are pretty good for flying, Sharovipteryx wanted to not be like other girls and used its legs instead. While it wasn‘t capable of powered flight (only birds, bats and pterosaurs ever accomplished that), it was probably a decent glider (Dyke, 2006).

From the same fossil beds as Sharovipteryx comes another unusual critter: Longisquama. At first glance it might look like your typical little lizard - if it wasn‘t for its back being covered with those long …scales? Feathers? Maybe just plant leaves that somehow fossilzed next to the animal? We really are not sure what exactly is going on with the back of this little guy. Although it seems like the most recent idea is, that those appendages are not feathers in the sense that birds have them, but that both feathers and Longisquama‘s structures might be homologous, meaning that they come from the same origin (Buchwitz, 2012). As for what were they doing with the structures? Probably sexual display, which is the paleontology version of saying “we‘re not sure, but unless you‘ve got a better idea, we‘re sticking with this one“.

(Oh, and btw both Longisquama and Sharovipteryx are prime topics for David Peters, self-proclaimed paleontologist that apparently loves to spread misinformation and seems to have beef with the entire paleo-community - so be cautious when you see something written by him. Man, I really don‘t wanna be involved with paleo drama. I wasn‘t even aware there was paleo drama)

The placement of both Sharovipteryx as well as Longuisquama on the family tree is pretty uncertain, but most likely they fall somewhere around the base of the Archosaur lineage, a group that you will hear a lot about in the future, as it includes the flying pterosaurs, everything related to crocodiles, and of course the dinosaurs. The earliest of those you might see around this time in the form of medium-sized average-looking bipeds like Nyasasaurus.

Also settled around the base of the archosaur line is long necked Tanystropheus (although some of its fossils were believed to be flying pterosaurs for a long time because its neck vertebrae were mistaken for wing finger bones). With a length of around 5 m it was pretty big for the time. It most likely lived a semi-aquatic lifestyle, staying on the shores while it used it oversized neck to catch fish from the water.

During the Triassic we see quite a few reptile groups going for more aquatic lifestyle. While some, like the Thalattosaurs were relatively short-lived, others dominated for most of the age of reptiles. One of the most prominent groups are the Sauropterygia. The name (which translates to “lizard flippers“) might not sound too familiar, but this is the group that will later contain the Loch-Ness-monster looking plesiosaurs and their shorter-necked cousins, the pliosaurs. In the early days of this group the animals weren‘t quite as well adapted for the waters yet, but you can already see were the journey is going. Nothosaurus for examples, lived probably similar to seals, while Placodus was more terrestrial and only spent time in the water to forage for food.

Most of this was all very reptile-focused. That is because by now the synapsids, those early cousins of our own lineage, that roamed the world as giant beasts during the permian, had lost their positions at the top of the food chain. For the most part, they were now constrained to small burrows and dark nights, to the shadows of much larger creatures. Their story does of course not end here, but for the next 170 million years our planet truely was a planet of reptiles.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Results from last nights paleostream

Sleepy Cacops showing its bizarre teeth.

Pliosaurus funkei having fun splashing around .

Pampaphoneus giving a Endothiodon a kiss with its sabers.

Ufudocyclops & Euparkeria.

#paleoart#paleostream#sketchbook#paleontology#20 minute sketch#Cacops#Pliosaurus#pampaphoneus#ufudocyclops

4 notes

·

View notes