#Edward Seymour ii

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

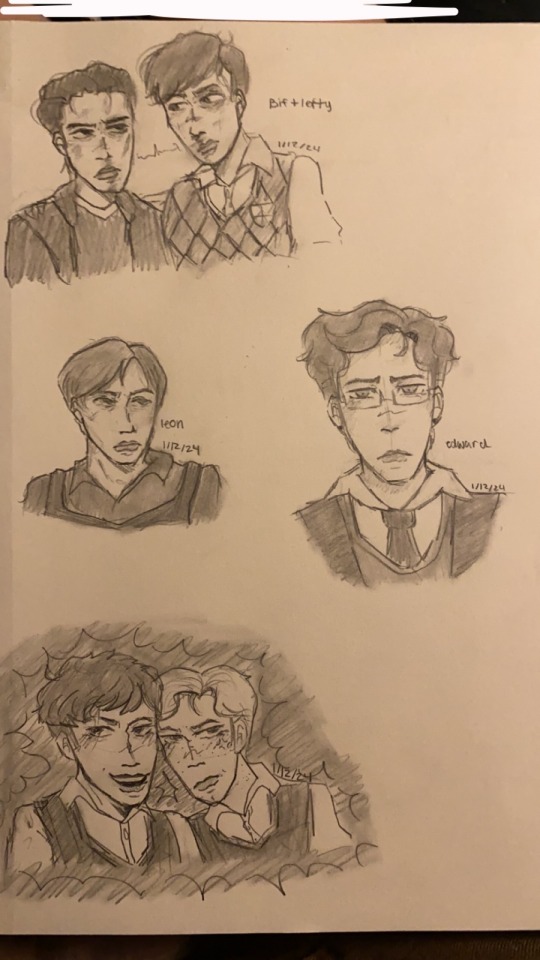

Please thank Edward Seymour II for getting me out of some art block.

#bully scholarship edition#bully canis canem edit#canis canem edit#bully anniversary edition#bully cce#bully rockstar#bullworth academy#bully prefects#edward seymour ii

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

I GOT A ART BOOK:3

also thanks @biftaylors for the ideas to draw… sighhhhhhhh

#bully scholarship edition#canis canem edit#bully fanart#gary smith#jimmy hopkins#leon kennedy#edward seymour II#smopkins#lefty mancini#bif taylor

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

It may be 1:30 am for me and I may be running on 2 hours of sleep and 2 liters of soda but eh fuck it

Here's my attempt at drawing the prefects cause I love them sm and they deserve more content

#bully scholarship edition#bully canis canem edit#canis canem edit#Seth kolbe#Max mactavish#Edward seymour II#Karl branting#But fr I am obsessed with them#Specially Seth and Max#The prefects deserve more love#bully fanart

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

Your blog banner is a 10/10 🤌

Thank you❤️ I’m planning to add stuff to it soon (this is an example btw of how it will look in the future)

Also yes that sims picture is mine. I made the prefects in the sims 4

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

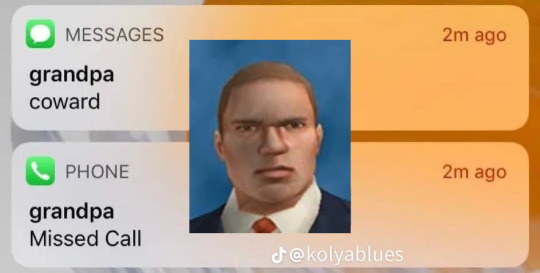

Me, after making these: I’m the smartest person alive

#bully se#bully scholarship edition#bully cce#bully canis canem edit#canis canem edit#bully anniversary edition#rockstar bully#bully rockstar#jimmy hopkins#gary smith#pete kowalski#seth kolbe#edward seymour ii#prefects#bully prefects

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

#bully scholarship edition#canis canem edit#meme#dr crabblesnitch#edward seymour ii#bullworth prefects#bullworth faculty#peanut romano#mintys 2 cents

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been doing some research into some royal genealogy, particularly the matrilineal heritage of the British royals. I found this interesting (mostly matrilineal) connection between Elizabeth II and Elizabeth I, and four of the six wives of Henry VIII!

It's sort of well-known that you can only trace Elizabeth II's matrilineal heritage back maybe six generations. But her great-grandmother, Louisa Burnaby, married into the Cavendish-Bentinck family. If you go up two males (the only two guys necessary!), then you can make a straight female-only connection to the Boleyns, Howards, and Seymours to Henry VIII and his daughter Elizabeth I!

I don't know if anyone has found this before, but I think it's really cool! Enjoy this chart I made that summarizes the whole connection.

#genealogy#royals#british monarchy#monarchy#queen elizabeth ii#elizabeth ii#henry viii#matriarchy#elizabeth i#edward vi#anne boleyn#jane seymour#catherine howard#catherine parr

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

#mary i#edward seymour#eustace chapuys#charles brandon#Richard III#thomas cromwell#phillip of bavaria#Phillip II

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Below the cut I have made a list of each English and British monarch, the age of their mothers at their births, and which number pregnancy they were the result of. Particularly before the early modern era, the perception of Queens and childbearing is quite skewed, which prompted me to make this list. I started with William I as the Anglo-Saxon kings didn’t have enough information for this list.

House of Normandy

William I (b. c.1028)

Son of Herleva (b. c.1003)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 25 at birth.

William II (b. c.1057/60)

Son of Matilda of Flanders (b. c.1031)

Third pregnancy at minimum, although exact birth order is unclear.

Approx age 26/29 at birth.

Henry I (b. c.1068)

Son of Matilda of Flanders (b. c.1031)

Fourth pregnancy at minimum, more likely eighth or ninth, although exact birth order is unclear.

Approx age 37 at birth.

Matilda (b. 7 Feb 1102)

Daughter of Matilda of Scotland (b. c.1080)

First pregnancy, possibly second.

Approx age 22 at birth.

Stephen (b. c.1092/6)

Son of Adela of Normandy (b. c.1067)

Fifth pregnancy, although exact birth order is uncertain.

Approx age 25/29 at birth.

Henry II (b. 5 Mar 1133)

Son of Empress Matilda (b. 7 Feb 1102)

First pregnancy.

Age 31 at birth.

Richard I (b. 8 Sep 1157)

Son of Eleanor of Aquitaine (b. c.1122)

Sixth pregnancy.

Approx age 35 at birth.

John (b. 24 Dec 1166)

Son of Eleanor of Aquitaine (b. c.1122)

Tenth pregnancy.

Approx age 44 at birth.

House of Plantagenet

Henry III (b. 1 Oct 1207)

Son of Isabella of Angoulême (b. c.1186/88)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 19/21 at birth.

Edward I (b. 17 Jun 1239)

Son of Eleanor of Provence (b. c.1223)

First pregnancy.

Age approx 16 at birth.

Edward II (b. 25 Apr 1284)

Son of Eleanor of Castile (b. c.1241)

Sixteenth pregnancy.

Approx age 43 at birth.

Edward III (b. 13 Nov 1312)

Son of Isabella of France (b. c.1295)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 17 at birth.

Richard II (b. 6 Jan 1367)

Son of Joan of Kent (b. 29 Sep 1326/7)

Seventh pregnancy.

Approx age 39/40 at birth.

House of Lancaster

Henry IV (b. c.Apr 1367)

Son of Blanche of Lancaster (b. 25 Mar 1342)

Sixth pregnancy.

Approx age 25 at birth.

Henry V (b. 16 Sep 1386)

Son of Mary de Bohun (b. c.1369/70)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 16/17 at birth.

Henry VI (b. 6 Dec 1421)

Son of Catherine of Valois (b. 27 Oct 1401)

First pregnancy.

Age 20 at birth.

House of York

Edward IV (b. 28 Apr 1442)

Son of Cecily Neville (b. 3 May 1415)

Third pregnancy.

Age 26 at birth.

Edward V (b. 2 Nov 1470)

Son of Elizabeth Woodville (b. c.1437)

Sixth pregnancy.

Approx age 33 at birth.

Richard III (b. 2 Oct 1452)

Son of Cecily Neville (b. 3 May 1415)

Eleventh pregnancy.

Age 37 at birth.

House of Tudor

Henry VII (b. 28 Jan 1457)

Son of Margaret Beaufort (b. 31 May 1443)

First pregnancy.

Age 13 at birth.

Henry VIII (b. 28 Jun 1491)

Son of Elizabeth of York (b. 11 Feb 1466)

Third pregnancy.

Age 25 at birth.

Edward VI (b. 12 Oct 1537)

Son of Jane Seymour (b. c.1509)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 28 at birth.

Jane (b. c.1537)

Daughter of Frances Brandon (b. 16 Jul 1517)

Third pregnancy.

Approx age 20 at birth.

Mary I (b. 18 Feb 1516)

Daughter of Catherine of Aragon (b. 16 Dec 1485)

Fifth pregnancy.

Age 30 at birth.

Elizabeth I (b. 7 Sep 1533)

Daughter of Anne Boleyn (b. c.1501/7)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 26/32 at birth.

House of Stuart

James I (b. 19 Jun 1566)

Son of Mary I of Scotland (b. 8 Dec 1542)

First pregnancy.

Age 23 at birth.

Charles I (b. 19 Nov 1600)

Son of Anne of Denmark (b. 12 Dec 1574)

Fifth pregnancy.

Age 25 at birth.

Charles II (b. 29 May 1630)

Son of Henrietta Maria of France (b. 25 Nov 1609)

Second pregnancy.

Age 20 at birth.

James II (14 Oct 1633)

Son of Henrietta Maria of France (b. 25 Nov 1609)

Fourth pregnancy.

Age 23 at birth.

William III (b. 4 Nov 1650)

Son of Mary, Princess Royal (b. 4 Nov 1631)

Second pregnancy.

Age 19 at birth.

Mary II (b. 30 Apr 1662)

Daughter of Anne Hyde (b. 12 Mar 1637)

Second pregnancy.

Age 25 at birth.

Anne (b. 6 Feb 1665)

Daughter of Anne Hyde (b. 12 Mar 1637)

Fourth pregnancy.

Age 27 at birth.

House of Hanover

George I (b. 28 May 1660)

Son of Sophia of the Palatinate (b. 14 Oct 1630)

First pregnancy.

Age 30 at birth.

George II (b. 9 Nov 1683)

Son of Sophia Dorothea of Celle (b. 15 Sep 1666)

First pregnancy.

Age 17 at birth.

George III (b. 4 Jun 1738)

Son of Augusta of Saxe-Gotha (b. 30 Nov 1719)

Second pregnancy.

Age 18 at birth.

George IV (b. 12 Aug 1762)

Son of Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (b. 19 May 1744)

First pregnancy.

Age 18 at birth.

William IV (b. 21 Aug 1765)

Son of Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (b. 19 May 1744)

Third pregnancy.

Age 21 at birth.

Victoria (b. 24 May 1819)

Daughter of Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saafield (b. 17 Aug 1786)

Third pregnancy.

Age 32 at birth.

Edward VII (b. 9 Nov 1841)

Daughter of Victoria of the United Kingdom (b. 24 May 1819)

Second pregnancy.

Age 22 at birth.

House of Windsor

George V (b. 3 Jun 1865)

Son of Alexandra of Denmark (b. 1 Dec 1844)

Second pregnancy.

Age 20 at birth.

Edward VIII (b. 23 Jun 1894)

Son of Mary of Teck (b. 26 May 1867)

First pregnancy.

Age 27 at birth.

George VI (b. 14 Dec 1895)

Son of Mary of Teck (b. 26 May 1867)

Second pregnancy.

Age 28 at birth.

Elizabeth II (b. 21 Apr 1926)

Daughter of Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon (b. 4 Aug 1900)

First pregnancy.

Age 25 at birth.

Charles III (b. 14 Nov 1948)

Son of Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom (b. 21 Apr 1926)

First pregnancy.

Age 22 at birth.

377 notes

·

View notes

Text

❝𝙔𝘼𝙉𝘿𝙀𝙍𝙀 𝙃𝙄𝙎𝙏𝙊𝙍𝙄𝘾𝘼𝙇 𝘾𝙃𝘼𝙍𝘼𝘾𝙏𝙀𝙍𝙎 𝙈𝘼𝙎𝙏𝙀𝙍𝙇𝙄𝙎𝙏❞

Headcanons

📜 Yandere Alexander the Great Headcanons (General)

📜 Yandere Julius Caesar Headcanons (General)

📜 Yan!Alexander the Great Random Headcanons

📜 Yan!Julius Caesar Random Headcanons

📜 Yandere Henry VIII w/Mistress!Reader Headcanons (Romantic)

📜 Yandere Henry VIII/Anne Boleyn Headcanons (Poly!Romantic)

📜 Yan!Husband Genghis Khan Headcanons (Romantic)

📜 Yandere Baldwin IV/Leper King Headcanons (General)

📜 Yan!Husband Henry VIII Headcanons (Romantic)

📜 Yan!Parents Henry VIII/Anne Boleyn w/Son!Reader Headcanons (Platonic)

📜 Yan!Alexander the Great w/Soldier's Pregnant Widow!Reader Headcanons (Romantic)

📜 Cyrus and Aella Headcanons (The Lost Queen)

📜 Yan!Husband Alexander the Great Headcanons (Romantic)

Imagines

📜 Poison | Yan!Alexander the Great

📜 Bucephalus | Yan!Alexander the Great

📜 Opal Necklace | Yan!Alexander the Great

📜 Night Time | Yan!Julius Caesar

📜 Persian Queen | Yan!Alexander the Great

📜 Handmaiden | Yan!Alexander the Great

📜 Handmaiden - II | Yan!Alexander the Great/Yan!Roxanna

📜 Sculpture | Soft!Yan!Alexander the Great

📜 Wedding Gifts | Soft!Yan!Alexander the Great

📜 Kitten Pajamas | Soft!Yan!Alexander the Great

📜 In the middle of the night | Soft!Yan!Alexander the Great

📜 Awake | The Lost Queen!Cleitus

Long Fics

📜 The Lost Queen | Yan!Alexander the Great

NSFW Alphabets

📜 Yan!Alexander the Great NSFW Alphabet

Scenarios

coming soon...

Prompts

📜 Yandere Alexander the Great | [6]

Love Letters

📜 Yandere Julius Caesar (Romantic)

📜 Yandere Alexander the Great (Romantic)

📜 Yandere Alexander the Great (Romantic)

📜 Yandere Alexander the Great (Romantic)

📜 Yandere Julius Caesar and Yandere Alexander the Great w/Pregnant!Reader (Romantic)

📜 Yandere Alexander the Great after the birth of the twins (Romantic)

📜 Yandere Alexander the Great (Platonic)

📜 Yandere Simon Bolivar (Romantic)

📜 Yandere Alexander the Great (Romantic)

📜 Yandere Alexander the Great w/Wife!Reader (Romantic)

📜 Yandere Henry VIII w/Wife!Reader (Romantic)

📜 Yandere Alexander the Great and Julius Cesar w/Wife!Reader (Romantic)

📜 Yan!Alexander the Great, Yan!Julius Caesar, Yan!Napoleon Bonaparte and Yan!Henry VIII w/Cheat Wife!Reader (Romantic)

📜 Yan!Alexander the Great w/Twins!Children (Platonic)

📜 Yandere Napoleon Bonaparte and Yandere Marquis de Lafayette w/Wife!Reader (Romantic)

📜 Yandere Alexander the Great and Yandere Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror (Romantic)

📜 Reader Love Letter for Julius Caesar (Romantic)

📜 Yan!Julius Caesar to Yan!Cleopatra

📜 Yandere Mehmed the Conqueror (Romantic)

📜 Yandere Pompey the Great (Romantic)

📜 Yandere Catherine of Aragon (Platonic)

📜 Yandere Catherine of Aragon w/Brother!Reader (Platonic)

📜 Yandere Baldwin IV (Romantic)

📜 Yandere Caesar Augustus (Romantic)

Reactions

📜 Yandere Alexander the Great Reaction: If Reader isn't a virgen

📜 Yan!Henry VIII being able to marry his Mistress!Reader

📜 Yandere Alexander the Great w/Christian!Reader

📜 Yandere Alexander the Great/Generals with a Shy!Reader

📜 Reaction to Reader wanting to have more than 5 children | Henry V, Napoleon Bonaparte, Charles Brandon, Henry VIII, Francesco Pazzi, Lorenzo de' Medici, Edward Seymour

#masterlist#yandere historical characters#yandere history#yandere historical characters masterlist#yandere au#history

454 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edward strikes again.

#someone pls get this reference PLEASEE#HOTDOG WATER#bully scholarship edition#bully canis canem edit#canis canem edit#bully anniversary edition#bully cce#bully rockstar#bullworth academy#bully prefects#edward seymour ii

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

ace attorney x bully prefects tf

#bully scholarship edition#canis canem edit#bully fanart#edward seymour ii#phoenix wright#ace attorney#ace attorney fanart

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

Did Edward I have a serious tendency towards violence towards Edward II?

I highly recommend reading Hannah Kilpatrick's article "Edward I’s Temper" in The Medieval Chronicle, vol. 12 (2019, doi) if you can find it because not only is it brilliant but because my entire answer will based on it. The short answer: probably not, because our main sources for Edward I being violent are two accounts that have been mistranslated or mistranscribed.

In a way, it's understandable. Edward I has frequently been understood as the ultimate embodiment of the brutal, dark and hyper-violent Middle Ages and the story that he physically assaulted his son both not only feeds this image but is likewise fed by this reputation. It becomes cyclical: we know Edward I was violent and angry because we know he assaulted his son and we know he assaulted his son because we know he was violent and angry. The actual story of this assault is goes something like this: the future Edward II foolishly petitions his father for an earldom for his unworthy and unpopular favourite Piers Gaveston. The king erupts in a fit of violent temper. He swears at his son, tears out handfuls of his son's hair and then throws him to the ground and kicks him.

This account is a conflation of two contemporary accounts, one found in the chronicle of Walter of Guisborough (where Edward II's hair is pulled out) and the other in the Fineshade chronicle (where Edward II is thrown to the ground and trampled). Kilpatrick argues, quite convincingly, that both accounts have been misread - mistranslated or mistranscribed - and offers corrections wherein Edward I's violence is directed at himself (he pulls his own hair out) and the physical copy of Edward II's petition, not his son.

On Walter of Guisborough:

But here is no assault. Walter of Guisborough never claims that Edward I tore out his son’s hair. ‘Et apprehensis capillis vtraque manu dilacerauit eos in quantum potuit’, he writes, following Edward I’s last speech, literally: ‘And seizing hair in each hand he tore it out to the extent that he could’, with no possessive pronoun. In English, of course, we cannot leave the ownership of a body part ambiguous—we would have to say ‘his own hair’, or‘his son’s hair’—but this construction is perfectly possible in Latin. In fact, in the absence of grammatical indications to the contrary, it should be assumed to refer back to the subject, as in Latin’s modern descendents—and as we see here with reference to the hands (‘manu’, not ‘manusua’).

In short, an alternative, more plausible translation of the original Latin is that Edward I tore out his own hair in a rage at his son's request, not his son's hair. It is violent, but violence directed to the self rather than at his son.

In regards to the Fineshade chronicle, Kilpatrick argues that George Haskins's transcription of the scene features an error. That is, he silently expanded the abbreviated pronoun, ipm, to the masculine form, ipsum:

For reasons of grammar and syntax, I argued that ipm should, in fact, be expanded to feminine ipsam: in other words, it is the petition which is flung to the ground and crushed underfoot (‘peticionem importunam ferens, indignanter ipsam ad terram deiecit pedibusque conculcauit’). The most recent masculine referent is the king himself, preceded by Gaveston; and it would be syntactically awkward to have to reach back past so many clauses to a previous sentence, when a more immediate and logical referent is (as it were) directly to hand.

So, rather than Edward I flinging his son to the ground and kicking him, Edward I flings the petition, an inanimate object, to the ground and tramples it.

To me, Kilpatrick's alternate readings of these chronicles are more believable. Seymour Phillips also has rejected Walter of Guisborough's account as "exaggerated" and either inaccurate or unable to be confirmed, but without reassessing the chronicle accounts that Kilpatrick does. The acceptance of this story speaks to what Kilpatrick calls "modern preconceptions of medieval emotionality" - the tendency to read the Middle Ages as a place of casual and excessive violence and to stereotype medieval individuals as being unable to control their emotions.

This accounts, Kilpatrick goes to argue, also use "public emotionality" or the public performance of emotion - in this case, lordly anger - to make a point. That is, that Edward I's anger serves a political and social purpose:

...public demonstrations of anger had a paradoxically crucial role in mending social bonds (particularly between a lord and his dependent), by 'announcing to all that the current situation was unacceptable and that social relationships would have to be restructured'. This would (ideally) initiate the process of negotiation and reconciliation.

Both writers use this display of lordly anger in different ways to achieve different messages in their writing but both are "interrogat[ing] the idea of effective kingship". Walter of Guisborough's account is more critical of Edward I, whilst also anticipating problems in his heir's reign. In contrast, the Fineshade chronicler is writing in the last decade of Edward II's reign and is more concerned with the failures of Edward II's kingship in comparison with his father's more stable reign.

So, Walter of Guisborough depicts Edward I's anger as dysfunctional, showing Edward as embodying Ira, uncontrolled and self-destructive rage while Edward II's lack of response to his father's anger is problematised because Edward II should be filled with a shaming anger that drives him to correct his fault (the favouritism of Gaveston):

In the scene as written, the king enacts a powerful and very public demonstration of the extent of the prince’s transgression against both his own role and his father’s, and of the serious breach in the relationships between father and son and between the realm and its future king. He attempts to solve it by trying to prick on his son to be the honourable knight that he ought to be. He fails—he does succumb to a violent, uncontrollable passion—not because he is a medieval man, but because Walter of Guisborough was critiquing specific flaws in his kingship. His transgression is not physical violence but violence against social norms governing acceptable emotional display: not the uncontrollable outburst of a passion that ought to be contained, but a failure to embody what it is to be a king, to engage and empower the emotionality of his followers.

In Fineshade chronicler's narrative, Edward I is idealised as the representation of "the stability and the link with the past that his son rejects" which renders the idea it depicts Edward violently assaulting his son even more suspect. Instead, the petition is trampled in an appropriate display of royal anger: "the transference of royal violence onto the petition (and the imagined Gaveston) rather than the body of his son allows the king to make a powerful performance of his fury without violating the feudal bond in return."

In brief, then: our evidence for Edward I's "serious tendency for violence" against his son comes from one event that has likely been misread (mistranslated, mistranscribed) and show Edward's violence enacted on his own body or an inanimate object rather than the body of his son. Seymour Phillips and Kathryn Warner both point out there was no serious breach between father and son, no suggestion that Edward I was disappointed with his son and, while there were conflicts between them, they were not unusual for a king and his son (n.b. Warner believes Walter of Guisborough's account is accurate, Phillips does not). The chronicle accounts may not have be a truthful depiction on what happened but a reflection on what made a good king and the function of lordly anger in kingship.

Of course, there's great difficulty in proving a negative. We know very little about the personal/private relationship between father and son (this is not unusual) and whether Edward I was ever violent towards his son (and if so, whether this would be seen as excessive or as indicative of a serious tendency towards violence) is something we don't and cannot know.

But what we can say is that our understanding of their relationship and the likelihood of its violence has been driven by our own tendency to stereotype history. Typically, the Middle Ages is seen as an extremely violent and backward time and Edward I as the ultimate representation of these impulses. Thus, he has been stereotyped as a particularly brutal and barbaric figure who would naturally enact excessive violence on his similarly-stereotyped son, read as a effeminate failure of kingship and manhood trapped in the "wrong time". Kilpatrick argues, quite convincingly in my opinion, that the supposed evidence or "proof" of Edward I's excessive violence and temper towards his son is no such thing. The reality of their relationship was undoubtedly much more complex.

Again, I really recommend you read the full article because this is only a summary of the broader points made.

(Also, I apologise if the quotes have mistakes in them. When I copied and pasted from the PDF I have, somehow the spaces between words didn't register so every word was smushed together. I've attempted to fix it but there may be some things I overlooked.)

#please anon(s) do not start asking me about edward i now#i know very little about him#(obviously this not to say to ed1 was nice & cuddly or the world's best dad but in this particular case he was probably not that awful)#edward ii#edward i#asks#anon#text posts#there's something about the idea that edward i's violence towards his son is our own modern reading of the scene#obviously it's most often a very homophobic fantasy: edward ii stands in for the stereotypical gay man subjected to violence#but some sympathetic authors use the story in a way to make readers emotionally connect with him#'you should feel sorry for him - look how awful his father is to him'#dare i say... as if they are putting him through a woobification process

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Someone take CapCut away from me

#I think Gary and petey need more solo things together idk#bully scholarship edition#bully se#bully anniversary edition#bully canis canem edit#bully cce#canis canem edit#gary smith#pete kowalski#edward seymour ii#Seth kolbe#bully prefects#prefects#prayeditis#video

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Beautiful Song

Voyager was a being ('A girl', she writes) that was not one for many words.

Voyager's handwriting was beautiful: perfectly cursive, yet Vertin did not see much, as it was direct and to the point:

'May I visit?'

The 'Your room' went unsaid; many Arcanists wonder what secrets lie in the illusive Timekeeper's room but, to either amazement or disappointment, it was just that: a room. Stacked documents, here and there, a bed that was yet to be made due to Vertin's sudden bolt out of the room and into the day; and now, a new addition, albeit one Vertin thinks is temporary.

Voyager stood politely, hands clasped in their front, the galaxies upon her stockings and dress shimmering in the gentle light of the room.

Vertin nodded at her. The being from beyond the stars preferred the silence, and Vertin respected it.

Voyager smiled back, before she started to play her violin. It's a familiar song, one Vertin has heard many times. Hearing it in the middle of the night was certainly a surprise, however.

She looked up the songs found on the Voayger spacecrafts, and this one was Greensleeves, a love song from the Tudor period, or thereabouts.

People oft believe it to be related to Henry VIII and his second wife, Anne Boleyn. However, the composition of the original piece was one of Italian origin, that only reached England after Henry's death, which would put it around the time of either Edward VI, Mary I or, most popularly, Elizabeth I.

Nevertheless, it is still associated with Henry VIII due to its themes around the singer wishing for their love to no longer 'cast them aside discourteously'; which is ironic, in the end, due to it being Henry who cast Anne aside in favour of Jane Seymour, leaving Anne to be beheaded for her crimes of adultery, incest and, worst of all, treason against the King of England.

Which, in retrospection, now has Vertin pondering: Did Voyager choose this song for a specific reason?

Voyager played the songs found, or even beyond, the Golden Records on the Voyager I and Voyager II spacecrafts. By that logic, she might have researched it, or guessed the meaning, behind each and every song.

Love was a foreign concept to the Timekeeper. Romantic love, she should specify.

She has experienced parental love from Ms. Tooth Fairy, her treating Vertin like a child. Granted, she did that to every child in the Foundation, but Vertin always felt she was focused more on by the dentist, perhaps out of a lighthearted exasperation on the Toothfairy collector's side. Likewise, Eternity doted on Vertin, treating her as a granddaughter, or something to the effect.

She has experienced the love of both a big and a little sister. Lilya treated Vertin like a younger sibling, with the Russian ace inviting Vertin to ride on the back of her Su-01ве, the two spending free afternoons just flying around The Wilderness.

The little sister is many, one being Mondlicht. The young huntress was grateful for the help the Timekeeper had given her to help defend against the big bad wolves. Recently, the girl had taken to trying to sleep for more than a few hours, Vertin often being the one to place a blanket over the German hunter.

The love of a friend, too; the likes of Horropedia, whom Vertin had since enjoyed the company of. He's a little eccentric, at times, but that adds to his charm. The two watch horror movies together, Horropedia explaining little parts of the movie, and Vertin listening.

The love of a... partner, however...

Schneider was a whirlwind. One that, with her sister and many good friends, was swept away by The Storm. Vertin believes that, in the short time they spent together, the love between two people was there.

Vertin did not know where to place Voyager. Listening again, she could hear the lyrics inside her head:

"You could not wish for anything,

Yet you still had it readily.

Sweet music still I play and sing;

But yet you will not love me..."

Voyager's smile wavered, looking at Vertin with a strange look in her eyes. She appeared... sad.

Did her love not return the same affection...?

Voyager stopped playing, letting go of her violin slowly, it floating and still playing Greensleeves.

The traveller of space gazed at the traveller of time.

A smile danced on the former's lips, that soon gently joined with the latter's lips.

Vertin had never been to space, but was fascinated by it. Yet, she was able to tell that Voyager tasted like star dust.

Vertin had drunk tea before this, but Voyager could still taste the true taste of the Timekeeper's lips.

Voyager let go of the lips of Vertin, the smile now unwavering, eyes glittering like the stars. She had no need for air, and were it not for Vertin's human lungs, she would have continued the caress of their lips forevermore.

Vertin blinked. "Ah."

"Hehe." Voyager giggled, a melodic sound.

With another blink, Vertin then came to a late revelation: It was she who was the Lady Greensleeves.

"...But... why...?" Vertin could never see herself in a light of good, but Voyager could.

"Shh..." she hushed, placing a finger over Vertin's lips, and one over her own.

Vertin faintly heard the violin stopping and playing a new song, but she was still dazed from everything.

'I don't understand,' she thought.

'Do not, then.' a gentle voice whispered back.

'But why?' she questioned.

'Should a reason exist?' the voice questioned back.

'...Am I loved?' she asked the Void.

'Yes. By everyone. Us. Me.' the Void answered back.

Voyager was a mysterious girl of a few words. Outwardly, of course.

Internally? An inner peace of voices, just waiting its chance and moment to be heard...

And the opportunity arrived with the girl with the top hat and beautiful freckles.

Distantly, Voyager heard the chorus:

"Greensleeves was all my joy,

Greensleeves was my delight;

Greensleeves, my heart of gold:

And who but my Lady Greensleeves?"

And vividly, Vertin heard The Chorus.

'Greensleeves, you are my joy,

Greensleeves, you are my delight;

Greensleeves, with a heart of gold:

I am glad to be yours, my Lady Greensleeves.'

#ryuusei's works#reverse 1999#r1999#vertin#r1999 voyager#reverse 1999 voyager#r1999 vertin#reverse 1999 vertin#vertin x voyager#I hereby dub this ship as: “Time & Space”

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ages of English Queens at First Marriage

I have only included women whose birth dates and dates of marriage are known within at least 1-2 years, therefore, this is not a comprehensive list. For this reason, women such as Philippa of Hainault and Anne Boleyn have been omitted.

This list is composed of Queens of England when it was a sovereign state, prior to the Acts of Union in 1707. Using the youngest possible age for each woman, the average age at first marriage was 17.

Eadgifu (Edgiva/Ediva) of Kent, third and final wife of Edward the Elder: age 17 when she married in 919 CE

Ælfthryth (Alfrida/Elfrida), second wife of Edgar the Peaceful: age 19/20 when she married in 964/965 CE

Emma of Normandy, second wife of Æthelred the Unready: age 18 when she married in 1002 CE

Ælfgifu of Northampton, first wife of Cnut the Great: age 23/24 when she married in 1013/1014 CE

Edith of Wessex, wife of Edward the Confessor: age 20 when she married in 1045 CE

Matilda of Flanders, wife of William the Conqueror: age 20/21 when she married in 1031/1032 CE

Matilda of Scotland, first wife of Henry I: age 20 when she married in 1100 CE

Adeliza of Louvain, second wife of Henry I: age 18 when she married in 1121 CE

Matilda of Boulogne, wife of Stephen: age 20 when she married in 1125 CE

Empress Matilda, wife of Henry V, HRE, and later Geoffrey V of Anjou: age 12 when she married Henry in 1114 CE

Eleanor of Aquitaine, first wife of Louis VII of France and later Henry II of England: age 15 when she married Louis in 1137 CE

Isabella of Gloucester, first wife of John Lackland: age 15/16 when she married John in 1189 CE

Isabella of Angoulême, second wife of John Lackland: between the ages of 12-14 when she married John in 1200 CE

Eleanor of Provence, wife of Henry III: age 13 when she married Henry in 1236 CE

Eleanor of Castile, first wife of Edward I: age 13 when she married Edward in 1254 CE

Margaret of France, second wife of Edward I: age 20 when she married Edward in 1299 CE

Isabella of France, wife of Edward II: age 13 when she married Edward in 1308 CE

Anne of Bohemia, first wife of Richard II: age 16 when she married Richard in 1382 CE

Isabella of Valois, second wife of Richard II: age 6 when she married Richard in 1396 CE

Joanna of Navarre, wife of John IV of Brittany, second wife of Henry IV: age 18 when she married John in 1386 CE

Catherine of Valois, wife of Henry V: age 19 when she married Henry in 1420 CE

Margaret of Anjou, wife of Henry VI: age 15 when she married Henry in 1445 CE

Elizabeth Woodville, wife of Sir John Grey and later Edward IV: age 15 when she married John in 1452 CE

Anne Neville, wife of Edward of Lancaster and later Richard III: age 14 when she married Edward in 1470 CE

Elizabeth of York, wife of Henry VII: age 20 when she married Henry in 1486 CE

Catherine of Aragon, wife of Arthur Tudor and later Henry VIII: age 15 when she married Arthur in 1501 CE

Jane Seymour, third wife of Henry VIII: age 24 when she married Henry in 1536 CE

Anne of Cleves, fourth wife of Henry VIII: age 25 when she married Henry in 1540 CE

Catherine Howard, fifth wife of Henry VIII: age 17 when she married Henry in 1540 CE

Jane Grey, wife of Guildford Dudley: age 16/17 when she married Guildford in 1553 CE

Mary I, wife of Philip II of Spain: age 38 when she married Philip in 1554 CE

Anne of Denmark, wife of James VI & I: age 15 when she married James in 1589 CE

Henrietta Maria of France, wife of Charles I: age 16 when she married Charles in 1625 CE

Catherine of Braganza, wife of Charles II: age 24 when she married Charles in 1662 CE

Anne Hyde, first wife of James II & VII: age 23 when she married James in 1660 CE

Mary of Modena, second wife of James II & VII: age 15 when she married James in 1673 CE

Mary II of England, wife of William III: age 15 when she married William in 1677 CE

108 notes

·

View notes