#Early Tang Dynasty (618–907AD)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Mulan (2020): A Scathing Review

Or, an extremely long rant by two extremely mad Chinese girls.

Before we (@hotaruyy and @meow3sensei) watched Mulan (2020), we didn’t expect too much, since the director and screenwriters aren’t Chinese (even though they claimed to want to be more culturally accurate). But holy shit, this film didn’t even fulfill our exceedingly low expectations (and we’re speaking as people who didn’t mind the loss of the musical aspect because look at the Beauty and the Beast live action). Our review will focus on our critiques of the presentation of different aspects of Chinese culture in Mulan (2020).

The Chinese Aspect of the film was especially infuriating to us as a Chinese audience. Disney emphasises that many of the changes made to the film in comparison to the animated film were to accommodate backlash regarding cultural and historical inaccuracies from Chinese audiences, but what we saw on the screen showed otherwise.

On Set Design (By a slightly irritated Architecture student)

Mix and match of architecture from multiple dynasties, which removes a lot of the sense of realism and authenticity from the film

Tang-style architecture is used (and if we’re being specific, Tang with hints of Song Dynasty) in the Imperial City’s set, which one would assume depicts the time period in which the movie is set in. Identified by the wooden balustrades, relatively simple and small dougong, vertical lattice windows, wooden piles for waterfront, organic shapes in landscape architecture etc. (fig. 1)

fig. 1 - Scene in film

Understandably, information on architecture before Tang (618-907AD) is scarce, so I do think there was an attempt at referencing the original poem that was written during the Southern and Northern Northern Wei Dynasty 南北朝北魏 (386-581AD). Taking creative liberty here makes sense.

That being said, the film didn’t care for retaining a consistent style of architecture, resulting in a wormhole of a set that somehow spans five different dynasties. Only two examples will be listed to avoid an entire essay :)

Exhibit A. Mulan’s home in Hakka Tulou 客家圍土樓 (fig. 2) (roughly translates to Hakka Mud Towers), which originated in the Song and Yuan dynasties (960-1368AD), and started maturing in the late Ming dynasty. (Why use something that didn’t even exist when the Ballad was written and by doing so, physically place Mulan in Fujian?? Just put her in an ambiguous village like how the animation did??). Somehow Tulou started existing before the Hakka clan migrated down south :) To put it simply the presence of Tulou is a locational and historical bug. The jump from the Hakka Tulou to the Tang-styled Imperial palace (fig. 3, which is strictly speaking a hybrid of different styles but I’d argue still mostly Tang) in the opening scenes is only a taste of the amount of inconsistencies later seen in the film.

fig. 2 Scene in film - Hakka Tulou

fig. 3 Scene in film - the Imperial Palace

Exhibit B. This scene (1:20:14) showing Qing Dynasty architecture in what is supposed to be a Tang Dynasty setting, identified by more elaborately decorated dougong 斗栱 (fig. 4 a key feature in the structural system in Chinese architecture, referring to the interlocking structure that sits on top of each column; at least three different kinds of dougong from three different dynasties have been spotted in the film).

fig. 4 Examples of different Dougong in Ancient Chinese architecture (top left being a good example of Tang-styled Dougong)

An insignificant building is not supposed to have more glamorous and larger dougong than the Imperial Palace, not to mention the lack of decorative dougong at all during the Tang Dynasty.

fig. 5 Scene in film that features a building with dougong

fig. 6 Shenyang Imperial Palace built in the Qing Dynasty

An actual Qing Dynasty Palace (fig. 6), for reference, and a random scene from the film (fig. 5). Note the larger dougong both fig. 5 and 6 (the ratio of dougong to column is significantly larger) with more layers of interlocking segments, as compared to the Tang-styled dougong that we pointed out earlier.

On Costume Design

Blue fabric on people who are NOT ROYALTY/NOBILITY. Soldiers guarding the imperial gate would not be wearing blue shirts under their armour. There wouldn’t be such a big supply of blue fabric in the first place; blue fabric would absolutely not be mass-produced for soldiers.

Ancient Chinese people made blue dye from crushed butterflies, did no one care enough to consider the sheer amount of wealth it takes to dye blue fabric organically? Soldiers would very simply not be wearing blue fabric because of how expensive these colours were at the time. Artistic liberty is fine but at least make it make sense in a clearly hierarchical society??

The painful inaccuracies in Mulan’s costume in the matchmaking scene (fig. 7). Ah, the scene that managed to translate breathtaking Hanfu (and there are plenty of resources to take inspiration from) into a Western caricature of a Chinese Halloween costume.

fig. 7 Scene in film featuring Mulan’s Hanfu from the matchmaking sequence

There’s nothing wrong with taking artistic liberties for costumes with a historical context. For instance, exaggerating certain characteristics of the era the story is in, or modernizing certain features so that they align with the character’s more modern way of thinking to contrast with the traditional setting. Good examples that come to mind are the costume designs in Marie Antoinette (2006), or Nirvana in Fire (2015), which also happens to be a Chinese period piece set in a fictional, historically ambiguous era. Inspiration for its costume design is taken from the Han Dynasty and the Southern and Northern Dynasties, so its costumes combine clothing silhouettes from the two periods, and use different characteristics such as colour to reflect class and status, and to represent characters’ personalities. It does a really good job of creating a new style while still giving subtle visual cues to the audience.

But Mulan’s dress can hardly be called an interpretation of traditional Chinese clothing. This is something the animated film did poorly on as well, and this probably contributed to the costume design in this film as an adaptation of the cartoon. The fabric had a shiny sheen that cheapened the costume. Coupled with the strange silhouette of the Hanfu (especially the bottom part of the skirt), this further detaches the audience from any hint of authenticity. The pictures below can speak for themselves. If they’re aiming for ambiguity in terms of the dynasties as seen in the set, then at least make something that is visually pleasing??

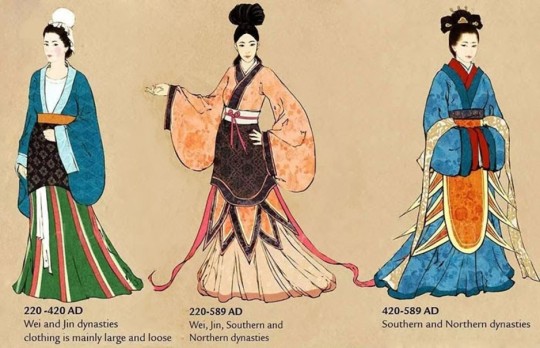

fig. 8 Evolution of Hanfu

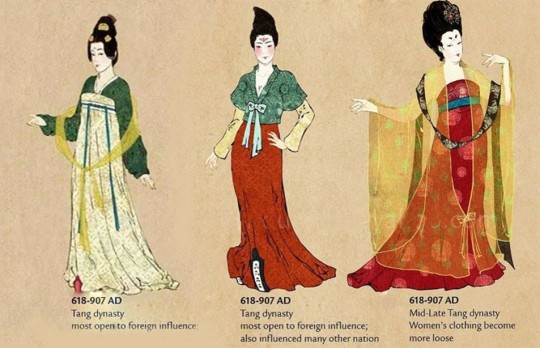

fig. 9 Tang Hanfu recreated with references from Tang artifacts (top: early Tang; bottom: golden era of the Tang period)

For whatever reason it seems like the extras in the background have more accurate costumes than the main character

And as a girl from a farming village why is she being trained like a noble lady??? A question I’ve had since the animated film…

The film wasn’t consistent when taking artistic liberties. Audiences subconsciously make visual connections to historical periods when watching a historical fiction film. It would be visually more cohesive if artistic liberties were taken on elements from one dynasty or by combining elements from dynasties with similar aesthetics, instead of jumping across centuries of very different stylistic approaches.

Basing the set design on the Tang Dynasty, but then including random shots of Qing Dynasty architecture of no particular importance (two very contrasting architectural styles); extras having Tang-style Hanfu, but Mulan not having one that's remotely close to any style of the multiple dynasties the film has taken inspiration from; alluding to the time period in which the ballad was written by painting Mulan’s forehead yellow 黃額妝 (which was poorly done but I digress), a style of makeup used by women of the Six dynasties and the Southern and Northern Dynasties (六朝女子), but everything else alludes to Tang or later. And finally, basing many things off the Tang Dynasty, but the Tang wasn’t in risk of invasion from the Huns or the Rouran??? We’re fucking confused :)

Small details like the ones we’ve listed above are visually off-putting; as an audience member I’m immediately thrown out of whatever universe the film is building due to the contradicting visual cues. If this was Disney’s and the director’s attempt at cultural accuracy, then it’s plainly insulting to the intelligence of their Chinese audience. (Respecting cultural concerns should not be Disney’s scapegoat for producing a bad movie.)

Ultimately, the film is based on a ballad and we wouldn’t say the points we’ve mentioned are considered common knowledge. So let’s treat it as a fictional era and put less significance on historical consistencies and authenticity. Let’s narrow it down to the crude representations (and misrepresentations) of general Chinese culture and society.

On Stereotypes

“Chi”: Why are soldiers receiving chi-related martial arts training, which takes years and years of elite, specialised training and experience? Ordinary soldiers don’t train their chi, they are not Wuxia 武俠 (roughly translates to martial arts chivalry). These people aren’t training for Jianghu martial art contests (江湖俠道的比武), they are training to kill for war, which does not require finesse at all. Even disregarding the lack of logic in training ordinary soldiers in martial arts (especially them teaching Taichi in the film), logistically it is simply not worth the economic and time cost of training entire regiments in martial arts only for them to be mostly killed off in battle. (Sorry, it’s difficult to explain wuxia and jianghu in a few words, but they’re super cool so please search them up if you’re interested!)

Many others on tumblr have commented on how chi itself is not the weird masculine "power" the film made it out to be, which is also very true (it's also actually very interesting so search it up if you want to!)

On Language as a Limitation

Clumsy translations of Chinese idioms and phrases that are just tragic comedy, e.g. 四兩撥千斤 being translated into “four ounces can move a thousand pounds”, which neglects the subtlety and gentle vibe of the original word choice while twisting the concept into something related to brute force or physics (but we guess this specific example is not entirely the screenwriters’ fault, since some English Taichi classes also translate it as that).

Replacing Chinese concepts and mythology directly with Western concepts such as witches, phoenixes rising from the ashes etc.

The single clumsy reference to the original “Ballad of Mulan” 雄兔腳撲朔,雌兔眼迷離;雙兔傍地走,安能辨我是雄雌?(translates to: when being held by the ears off the ground, male rabbits would have fidgeting front legs, while female rabbits close their eyes; who’s to tell male and female apart when the two rabbits are running side by side?) This line is an acknowledgement and compliment to Mulan’s intelligence and capabilities. It also challenges patriarchal beliefs of gender and women.

On Traditional Virtues (or the oversimplification of them, and a continuation of Language as a Limitation)

The film’s traditional values of 忠勇真 (translated as loyal, brave, and true in the film by using the most direct translations possible) and 孝 (translated as "devotion to family" in the film) seem to be a reference to the core values of Confucianism. We assume that the film is referencing these Confucian core values: 仁 (to be humane)、恕 (to forgive)、誠 (to be honest and sincere)、孝 (filial piety) and 尊王道 (to be loyal to the emperor). If the screenwriters were going to use traditional values, it is curious for them to choose only those three specifically, and to grossly simplify the actual values in their choice of Chinese characters (instead of using the conventional characters), then to grossly simplify them again in their English translations, and then to put them together in that order. The film also just briefly goes over the values by plainly listing them out in the form of an oath, thereby erasing the complexities of the values...

In a hilarious weibo post by 十四皮一下特别开心, they point out that the three values of 忠勇真 used in the film actually directly translate and correspond to the FBI motto of “Fidelity, Bravery, Integrity” :)

Let’s talk about 孝, the fourth traditional virtue engraved in the sword gifted to Mulan by the emperor at the end of the film. Over everything else, this is the original ballad’s central moral, and what we believe the film is also trying to evoke, so the weak translation diminishes the story’s message. The animation was smart in not directly translating it and instead demonstrates what it entails through the progression of the plot. The film does the opposite and translates it as “devotion to family”, when they could have just referred to it as filial piety. Care, respect, thankfulness and giving back to one’s parents and elderly family members. While obedience and devotion are part of what the virtue teaches, it's not supposed to sound like an obligation, it’s not something ritualistic, it’s just something everyone does as a “good” human being.

(And if the director and screenwriters were trying to diminish the role and significance of filial piety in the film on purpose because they wanted Mulan to appear “stronger” and “individualistic”, then… I really have no words for how painfully insensitive that is in terms of how white feminism does not and should not apply to or be imposed on other cultures.)

And here’s our list of Things That Also Pissed Us Off that other people on tumblr have talked about already, which is why we’re mentioning them without much elaboration:

On Feminism

We get that Disney was trying to make a female empowerment movie but they really missed the mark? Even with a female director, somehow. Stepping back and ignoring the Chinese aspects of the film, as a female audience this film was equally, if not more, hurtful

Mulan is only seen as “strong” because of her extraordinarily powerful “gift” of chi that led to her being physically more powerful than the men, especially in that scene where she lugs the two buckets of water to the peak of the mountain (which is in sharp contrast to how Mulan in the animated film is strong because she’s intelligent and is able to utilise teamwork and her strengths properly, and doesn’t let her understandable disadvantage in terms of physical strength trip her up)

All female characters are one-dimensional as fuck and are mere caricatures (though to be fair, the male characters aren’t treated much better) BUT PEOPLE, MULAN IS THE MAIN CHARACTER!! Her name is literally the name of the film!!! Maybe give her some character??? And what happened to wanting to produce good Asian representation in Hollywood???

The character of the witch was slightly more complex than everyone else, which, good for her, but then the screenwriters had her killed when she could easily have not been written with that conclusion to her arc?? Seems to us like some bullshit where the witch had to be punished in a narrative sense because she “succumbed” to using her powers (which are again dubiously chi-related) for “evil”, when instead she was merely trying to achieve as much as she could for herself in a patriarchal system designed to punish her

Plus the implication of writing the sequence of the witch sacrificing herself for Mulan is that Mulan is inherently more worthy of protection because she’s more “noble”, which, again, we call bullshit. Mulan achieved (impossible) success and validation in a patriarchal system because she played by their rules of what it means to be a masculine “warrior” and excelled, while the witch is scorned and punished within the story and also in a narrative sense because she doesn’t. Is that really what it means to be noble and good???? Does that really make Mulan superior to the witch?? (Honestly this plot point might have worked if there was more complexity written into the script, but unfortunately there wasn't)

Can’t believe they just threw away what could have been a perfectly complex and compelling relationship between Mulan and the witch because of shitty writing

The way Mulan lets her hair down and dumps her armour as an indication of her female identity (which is irritating to us on so many levels, as explained by various tumblr users)

On Production

Plot and character arcs have no emotional tension; they’re super rushed and super shallow; emotional beats are not hit properly (e.g. Mulan’s loyalty and friendship towards the soldiers, built up with one line from Honghui “you can turn your back on me...but please don’t turn your back on them” kind of bullshit)

The screenwriters would not know character depth or development even if it were shoved in their face

Blatant symbolism and metaphors (e.g. the fucking phoenix, and thank fuck it doesn’t look like a western phoenix) that make the film feel very… low.

Cinematography and editing: some very beautiful and compositionally interesting shots, but the battle scenes lack tension. The jump cuts disrupt the rhythm and intensity of the fighting; in combination with the overuse of slow motion, they drag the pace of the choreography and further slow down the rhythm of the scene. Exaggerated colour toning make certain scenes more fantastical than others, resulting in a mix of realistic landscapes in some scenes and highly saturated unnatural colours in others, which draws the audience in and out of the film’s universe. This is a shame because they actually took the effort to film in real landscapes.

fig. 10 Scene in film

Special effects: lack of blood in battle scenes (which, fine, they want it to be family-friendly) and Mulan’s suddenly clean face after she returns to her female identity visually puts off the audience (and links back to the issues surrounding the visual representation of her femininity)

And here’s the extremely short list of Things That We Liked:

That first fight scene between the witch and mulan when the witch brushes mulan’s hair away from her face with her claw while restraining her because that was gay as fuck and I am but a weak bisexual!!!

Donnie Yen’s action sequences lmao (they’re not even among the better ones he’s done so everyone go watch Ip Man for actually good action sequences and choreography)

Just listening to the soundtrack itself was great, loved the Reflection variations but I was simply too distracted by the other shitty things in the film

All-asian cast (thank fuck) with impressive actors and actresses (who should not be blamed for a shitty script)

TL;DR: This film is not worth your time or money. Inferior to the animated film (which already has a few questionable aspects). If you’re somehow really interested in seeing how badly Disney butchered Chinese culture (and to a certain extent the animated film), then just pirate this film. If you want to know what happened but can’t be bothered to waste your time watching the film, read this amazing and hilarious twitter thread by @XiranJayZhao, which we found right before we posted this review, and pretty much sums up our viewing experience as well.

Disclaimer: At the end of the day we're two girls from a predominantly Chinese society who are used to Chinese period films and dramas, watching Mulan (2020), a film primarily meant for Chinese diaspora and audiences in the West, with the Chinese market in Asia being just a secondary economic opportunity for Disney. We do realise that we aren't this film's target audience, and that we're not at all experts in everything we've discussed in this review. A lot of this is just us nitpicking, and all of it is just our personal (and very emotive) opinions from watching this film. Mostly we're just disappointed that the film was advertised to be relatively realistic and culturally accurate, but… wasn't.

Sigh.

Btw please feel free to ask us for recs of actually good, actually Chinese films and shows lmao.

Finally, all the love to our beta @keekry, for her many suggestions and hilarious comments!!!

#mulan#mulan 2020#mulan 1998#mulan live action#chinese culture#chinese architecture#chinese clothes#chinese costumes#chinese fashion#hanfu#mulan spoilers#long post#film review#disney#as a side note i have no idea why everyone thinks it's pronounced xian lang when in fact it's xian niang

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Li ZiQi, Who is she?

LI ZIQI – A Modern Chinese Fairy She is born in the 90s. She’s a girl who lived in the deep mountains of Sichuan (Szechwan), China. Unlike other online celebrities, although she’s famous on the Internet nowadays and always appears in beautiful clothes, Li ziqi was always wearing a modified version of Hanfu (a kind of Han Chinese traditional clothing) back then. She was using the most traditional method, the most traditional tools, but a unique perspective to present Chinese traditional dishes. She is a “Wonder Woman” in the eyes of her fans, as she can achieve what normal people cannot. Once again, she has shown people the styles of the Han(202BC-220AD) and Tang Dynasty(618-907AD) and let them know more about what life in the countryside is like. She also enables people to experience the life in the countryside which contemporary Chinese people strive for. For the people living in the cities, this would be like discovering the unknown and exploring an ideal way of life on the farm. People admire her, especially because she uses her own way to combine the elements of the ancient Chinese and the modern life, showing to her audience the traditional Chinese pastoral life and the process of Chinese food production. Her videos fully explain the Chinese people’s traditional concept of family, the Taoist thought of harmony between man and nature. Who is Li ziqi? Li Ziqi (Chinese: 李子柒)was born in the remote mountain village of northwestern Pingwu, Mianyang city, China. (Sorry, we can’t release much more personal information of her for protecting this beautiful girl.) She did not have a happy childhood like most of the children. When she was little, her parents got divorced and his father died early. Then, she started living with her grandparents. Their life was poor, but it was also relatively stable. Li Ziqi’s grandfather was a cook working in the countryside. When there was a ceremony going on, be it a wedding or a funeral, her grandfather would be in charge. In the videos, she showed how to cook various dishes, which she had learned from her grandfather. Besides cooking, she also learned how to make bamboo baskets, fishing, growing vegetables and doing carpenter work from her grandparents. Li ziqi ’s stories of growth At the age of 14, when most of the kids of the same age went to middle school, Li Ziqi dropped out of school and tried to support herself by doing various jobs. She has not been treated well, nor was her fate particularly good at the initial stage of her life. She struggled much to survive – she starved, slept in a cave under a bridge, worked as a waitress, an electrician, sold Hanfu, and she even worked as a DJ at a nightclub. However, after working for 7 to 8 years, it became clearer to her what she really wanted. It also helped her develop the ability to think and judge independently. Also, with all these experiences, she has developed a sense of ‘danger’. No matter what happens, she must keep enough deposits in her bank account in case there is an emergency. In 2012, her grandmother had a serious illness. Li Ziqi decided to give up everything and return to her hometown so that she could take care of her grandmother. The life at hometown was relaxing. She started work early in the morning and returned home late. Like other farmers who earned their living on the farm, she was living an ordinary life in the countryside.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Yunnan Xuanwei Ham (宣威火腿/xuān wēi huó tuǐ) Eben van Tonder 10 May 2020

Introduction

Xuanwei Han in Xuanwei City. Reference China on the Way.

Yunnan is one of China’s premium food regions known for exquisite tastes. One of the major cities in this picturesque region is Xuanwei, where one of the world famous Chinese hams are produced, the others being Jinhua Ham from Zhejiang province and Rugao Ham from Jiangsu province. Yunnan Xuanwei Ham is known for its fragrance, appearance, and out-of-the-world taste. Through the ages, there have been many references in literature to the health benefits associated with the hams. In order to produce these hams, there are at least two ingredients without which the hams can not be produced. The first ingredient is salt.

The Industrialisation of Ham

Early references to Xuanwei hams go back to 1766. “Old chronicles recorded the Qing emperor Yong Zheng five years (the year 1727) located XuanWei (a city of YunNan province, China), so it is called XuanWei ham. (China on the Way) In 1909, Zhuo Lin’s (Deng Xiaoping’s third wife) father Pu Zai Ting, a businessman, mass-produced it for the first time. He established Xuanhe Ham Industry Company Limited. His company sent food technicians to Shanghai, Guangzhou (formerly Canton), and Japan to learn advanced food processing technology.

One example of the excellence pursued in Guangzhou relates to the cultivation of rice. Rice breeding began in China in 1906. However, by 1919, systematic and well-targeted breeding using rigorous methodologies was started at Nanjing Higher Agricultural School and Guangzhou Agricultural Specialized School. Between 1919 and 1949, 100 different rice varieties were bred and released. (Mew, et al., 2003) For a riveting look at the trade in Guangzhou, see the work by Dr. Peter C. Perdue, Professor of History, Yale University, Canton Trade.

By all accounts, Pu Zaiting was successful in creating a world famous ham (at least by probably standardising and industrialising the process). In 1915 Xuanwei ham won a Gold Medal at Panama International Fair. The ham, which, in the Qing and Ming Dynasties, was a necessary gift for friends and guests and which, during the gourmet festival, became the main ingredient to create different delicious dishes achieved international acclaim. (chinadaily.com)

The Xuanhe Canned Ham Industry Company Limited was established on the back of canning equipment bought from the United States of America to produce canned ham. Most of what it produced were exported overseas. In 1923 Sun Yat-sen tasted the ham at the National Food Exhibition held in Guangzhou. Sun famously wrote of the ham, “yin he shi de” translating as “eat well for a sound mind!” By 1934, four companies were producing the canned ham. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

Xuanwei Ham expanded greatly under the People’s Republic of China, established in 1949. Supporting industries started to develop. A factory was created to supply the cans used by the Municipal Authority of Kunming City. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

Production of Xuanwei hams rose by 1999 to 13 000 tonnes, made by 38 large producers. In 2001 it got the status of a regional brand, protected by the People’s Republic of China. A Chinese standard, GB 18357-2003 was subsequently issued. By 2004 production rose to 20,750 tonnes with technology in manufacturing and packaging improving continuously. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

Apart from a rich and competitive environment, an entrepreneur, as the proverb goes, worth his salt, was needed to bring discipline to the production process and to establish this ham among the finest on earth. In achieving this status, three elements were required, namely salt, the right meat and a solid production technique to yield this culinary masterpiece on an industrial scale.

Yunnan – Centre of Culinary Excellence

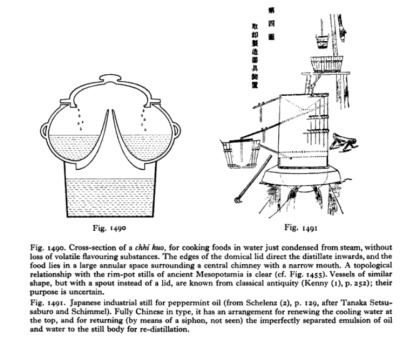

The first requirement for competitiveness is an environment of excellence and innovation. The environment where this exquisite ham is produced testifies to culinary excellence. Like Prague, which produced the ham press, nitrite curing and the famous Prague hams, the Yunnan hams likewise hail from an area replete with food and cooking innovations. Yunnan is located on what was known as the Southern Silk Road and its culinary excellence is seen, among other things, in the equipment used in preparing their foods. Joseph Needham, et al. reports that in restaurants in the cities of Yunnan, a very special dish is found “in which chicken, ham, meat balls and the like have been cooked in water just condensed from steam. This is done by means of an apparatus called chhi kuo (or formerly yang li kuo) made especially at Chien-shui near Kochiu. It consists simply of a red earthenware pot with a domical cover, the bottom of the pot being pierced by a tapering chimney so formed as to leave on all sides an annular trough (figure 1490). The chhi kuo once placed on a saucepan of boiling water, steam enters from below and is condensed so as to fall upon and cook the viands of the trough, resulting thus after due process in something much better than either a soup or a stew in the ordinary sense. Since the chimney tapers to a small hole at its tip no natural volatile substances are lost from the food, hence the name of the object and the purpose of its existence. The chhi kuo must claim to be regarded as a distant descendant of the Babylonian rim-pot (for it has and needs no Hellenistic side-tube) with the ancient rim expanded to form a trough, compressing the ‘still’-body to a narrow chimney. But how the idea found its way through the ages, and from Mesopotamia to Yunnan, might admit of a wide conjecture.” (Needham, et al.,1980)

The second essential ingredient for a salt-cured ham is salt. Salt is something that China has been specialising in for thousands of years and which became the backbone of the creation of this legend.

Salt in China

Flad, et al. (2005) showed that salt production was taking place in China on an industrial scale as early as the first millennium BCE at Zhongba. “Zhongba is located in the Zhong Xian County, Chongqing Municipality, approximately 200 km down-river along the Yangzi from Chongqing City in central China. Researchers concluded that “the homogeneity of the ceramic assemblage” found at this site “suggests that salt production may already have been significant in this area throughout the second millennium B.C..” Significantly, “the Zhongba data represent the oldest confirmed example of pottery-based salt production yet found in China.” (Flad, et al.; 2005)

Salt-cured Chinese hams have been in production since the Tang Dynasty (618-907AD). First records appeared in the book Supplement to Chinese Materia Medica by Tang Dynasty doctor Chen Zangqi, who claimed ham from Jinhua was the best. Pork legs were commonly salted by soldiers in Jinhua to take on long journeys during wartime, and it was imperial scholar Zong Ze who introduced it to Song Dynasty Emperor Gaozong. Gaozong was so enamored with the ham’s intense flavour and red colour he named it huo tui, or ‘fire leg’. (SBS) An earlier record of ham than Jinhua-ham is Anfu ham from the Qin dynasty (221 to 206 BCE).

In the middle ages, Marco Polo is said to have encountered salt curing of hams in China on his presumed 13th-century trip. Impressed with the culture and customs he saw on his travels, he claims that he returned to Venice with Chinese porcelain, paper money, spices, and silks to introduce to his home country. He claims that it was from his time in Jinhua, a city in eastern Zheijiang province, where he found salt-cured ham. Whether one can accept these claims from Marco Polo is, however, a different question.

Salt Production In and Around Yunnan

When it comes to salt, only a very particular variety is called on to create this legend.

Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau

Around the Yunnan-Guizhou plateau are three salt producing areas which took advantage of the expansion of China towards the west in the early modern era. “Szechwan with a slow but steady advance; Yunnan with the speed and initiative characteristic of a developing mining area; Mongolia with a sudden, temporary eruption.” (Adshead, 1988) As fascinating as Szechwan and Mongolia are, we leave this for a future consideration and hone in on Yunnan.

Szechwan not only supplied its own requirements for salt, but also that of Kweichow, Yunnan (trade started in 1726) and western Hupei. Despite the fact that Yunnan imported salt from Szechwan and possibly from Kwangtung, this was mainly to supply its eastern regions of the escarpment. On the plateau it had salt resources of its own. By 1800, it is estimated that it produced 375 000 cwt (hundredweight).”These salines formed three groups: Pei-ching in the west near Tali the old indigenous capital; the Mo-hei-ching or Shihi-koa ching in the south near Szemao close to Laotian and Burmese borders; Hei-ching in the east near the provincial capital Kunming. (Adshead, 1988) It is this last group that captures our imagination due to the connection with the Yunnan hams.

Although known as ching or wells, many of the Yunnan salines, especially those in the Mo-hei-ching group, were in the nature of shafts or mines, though the low grade rock salt was generally turned into brine and evaporated over wood fires. The growth of the Yunnan salines in the Ch’ing period was the product of two forces. First, Chinese mining enterprise, often Chinese Muslim enterprise, which in the 18th century was turning Yunnan into China’s major source of base materials – copper, tin and zinc. Second, the extension of direct Chinese rule into the area, the so-called kai-t’u kuei-liu, initiated particularly by the Machu governor-general O-er-t’ai between 1725 and 1732. (Adshead, 1988)

The distant past of Heijin comes to us, courtesy of Yunnan Adventure Travel, who writes that “the unearthed relics of stones, potteries, and bronze wares have proved that as early as 3,200 years ago, ancestors of some minority groups already worked and multiplied on this land. It’s recorded in the “Annals of Heijin” that, a local farmer lost his cattle when grazing on the mountain, he finally found his black cattle near a well; but to his surprise, when it lipped the soil around the well, salt appeared; thus in order to memorize the black well, the place was nicknamed as “Heiniu Yanjin” which means the black cattle and the salt well. It’s shortly referred to as Heijin afterwards.” (www.yunnanadventure.com) Some accounts of the story have it that it was a Yi girl who was looking for her missing oxen when she came upon them licking salt from the black well.

Who better to take us on a tour of the old town than a seasoned traveller! We meet such a wanderer in the old city of Heijin in the person of Christy Huang. She takes us on an epic adventure, discovering the old salt kingdom of Hei-ching. She posted it on Monday, November 30th, 2015 and she called her post “Old Towns of Yunnan, Heijing.”

Christy writes that “the quite fameless Old Town of Heijing (黑井古镇) – today one of the nicest in Yunnan – used to be famous for the high-quality salt which was produced there since hundreds of years. The once most important town of Yunnan is hidden at the banks of Longchuan River in Lufeng County of Chuxiong Prefecture of Yunnan.

Salt production in bigger scale began in the Tang Dynasty (618-907) and peaked during the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1912) Dynasties. Besides the overall beautiful picture of Hejing and its surroundings, there are a couple of scenic spots worth mentioning:

Courtyard of Family Wu,

Ancient Salt Workshop,

Dalong Shrine, as well as,

Heiniu Salt Well.

The Courtyard of Family Wu used to be the residence of former salt tycoon of Heijing Old Town. The mansion was built during 21 years in mid 19th century and is formed in the shape of the Chinese character wang (王), which means king. It has 108 rooms, which have been left more or less unchanged. Today it serves as an (expensive) hotel for Heijing visitors.

The Ancient Salt Workshop was Heijing’s core place and fortune fountain. The remaining huge water wheels and stages for making salt testify the great prosperity of the bygone times. The salt produced in Heijing is as white as snow. It was and is used for preserving Yunnan’s well-known Xuanwei Ham.” (Christy Huang, 2015)

Wujin pig

The third ingredient in the production of Yunnan Xuanwei Ham is the pigs. Traditionally, the rear legs of the Wujin pig breed are used. The breed is known for its high-fat content, muscle quality and thin skin (chinadaily.com).

The breed is usually kept outdoors and is typical in the Xuanwei region. They are normally fed on corn flour, soybean, horse bean, potato, carrot, and buckwheat. They are slow growers, but their meat is of superb quality.

Li Yingqing and Guo Anfei (China Daily) wrote a great article about these pigs for the Yunnan China Daily entitled “Yunnan’s little black pig by the Angry River.”

They write that “there is a quiet little revolution taking place by the banks of Nujiang River, the “angry river”, the upper stretch of the famous Mekong as it passes the narrow gorges near Lijiang. Here, little black pigs wander freely by steep meadows, grazing on wild herbs and foraging as freely as wild animals. They are relatively small, compared to their bigger cousins bred in farms. These sturdy little animals are reared for about two to three years before they are slaughtered and made into the region’s organic hams – called black hams for their deep-colored crusts.” (Yingqing and Anfei)

Li Yingqing and Guo Anfei report on “Wang Yingwen, a 47-year-old farmer who has raised the black pigs for more than 30 years, says the pigs are fed spring water and they live on wild fruits, mushrooms and ants on mountains, an all-organic diet if there was one. (Yingqing and Anfei)

With increased industrialisation came the demand for a faster growing animal. Wujin pigs were being crossed with Duroc (USA), Landrace (Denmark), and York (UK) to achieve faster growth. Wujin x Duroc were crossbred. Other crossbreeds are York x (Wujin x Duroc) and DLY (Duroc x (Landrace x York). Yang and Lu (1987) found that the cross itself does not materially influence the quality of the ham as long as the breed contains 25% Wujin blood. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

In Xuanwei City, pig production is big business! In 2004, the city loaned 120 million yuan to breeders. By this date, the city had 31 breeding facilities each yielding 3000 pigs annually. There were an additional 9600 small breeding facilities. 356 Animal hospitals support the breeding and husbandry operations. In Xuanwei City, 1.2 million pigs were sold in that year. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

Consumers want a great product (consistency, despite volumes offered by industrialised processes) and a great story (focussing on the ancient history of the process and ham itself). Work to accomplish this was funded by the Yunnan Scientific Department, the Yunnan Education Department and Xuanwei City Local Government who all promoted the continued development of the Yunnan Xuanwei Ham (宣威火腿/xuān wēi huó tuǐ). (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016) Modern processing methods moved away from seasonal production and embraced modern processing technology, but the great legends of the past remain as well as tailor-made production techniques catering for year-round production.

Processing Yunnan Xuanwei Ham

The Xuanwei climate explains the production methods used, as is the case with all the great hams around the world. Xuanwei City is located on a low-latitude plateau mansoon climatic area where the north sub-torrid zone, the southern temperature zone, and the mid-temperature zone coexist. Winter lasts from November to January and spring occurs from February to April. February, March, April is sunny and clear and this leads to a low relative humidity during these months. From March to September it is overcast and rainy, and the relative humidity is comparatively high. Winter is the best time to salt the hams according to the old methods to limit microactivity till salt dehydrates the meat and reduces the water activity. The rainy season is best for fermenting the ham. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

Production

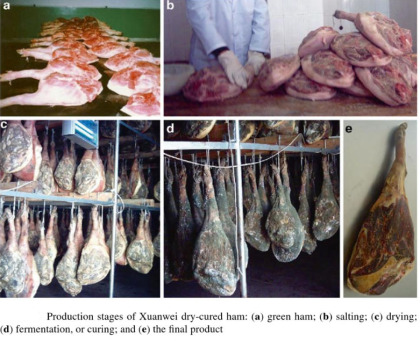

As in all meat processing, making the hams start with good meat selection. The process starts in the winter. The animal is killed and all the blood pressed out by hand. Animals are between 90 and 130 kg (live weight) when slaughtered.

by Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016

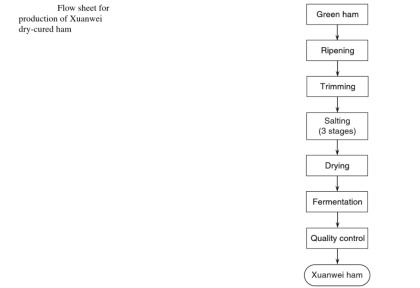

A simple flow chart is given by Kristbergsson and Oliveira (2016).

Slaughtering and Trimming

Boiling water and scraping the pig’s hair. Reference: China on the Way.

Traditionally Xuanwei people kill the pigs usually before the last frost. They add boiling water to a wok and scrape the pig’s hair. Some people refer to killing the pig as washing the pig. For villagers, the killing of the pig is a sacred ceremony. (China on the Way)

The hind leg is trimmed into an oval shape in the form of a Chinese musical instrument, the pipa. The legs of small pigs are cut in the form of a leaf. The legs cut off along the last lumbar vertebra. After the blood is pressed out, the meat is held for ripening in a cold room at a temperature of 4 to 8 deg C, relative humidity of 75% for 24 hours. Ripened legs are known as green hams. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016) This step is an enigma to me since I am not sure what is accomplished in such a short period of time. My guess is that it is not technically ripening, but rather allowing any excess fluids to drain out. I will keep interrogating the processing steps to ensure that my sources have the right information.

Cutting and trimming the leg: China on the Way.

Salting

The First Salting: China on the Way.

The green hams are then salted. The salt is a mixture of table salt (25g/kg of leg) and sodium nitrite (0.1g/kg leg). (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016) The inclusion of sodium nitrite is without question a modern development since nitrite curing of meat only became popular after World War I. My instinct tells me that they originally only used salt and later, possibly, sodium nitrate, the production of which has been done for very long in Chinese history.

The salt is rubbed into the hams by hand massaging for around 5 minutes. “The salted hams are then stacked in pallets and held in a cold room at 4 to 8 deg C, 75 to 85% relative humidity for 2 days. Salting procedure is then repeated.” The salt ratios are this time changed to table salt of 30g/kg ham and sodium nitrite is kept at 0.1g/kg leg. The meat is rested for a further 3 days in the chiller after which another salting is done. The ratio of this salting is 15g of table salt per kg of ham and again, sodium nitrite is kept at 0.1g per kg ham. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

Kneeing the hams as salt is rubbed in by hand: China on the Way.

According to Li Yingqing and Guo Anfei, “traditionally made hams are cured with half the salt used in factories. Instead, they are allowed to dry-cure for at least eight months to about three years, so the meat has time to mellow and mature.” “The longer the ham is cured, the better the quality and the most popular product now is the three-year-old cured ham.”

Double Salted Hams: China on the Way.

Drying

The hams are then hung in the drying room with a temperature of 10 to 15 deg C and relative humidity of between 50 and 60%. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016) Note how the temperature is increased and the relative humidity decreases to facilitate drying from the inside, out.

The excess salt is brushed away and the hams are dried for 40 days. Windows are kept open to facilitate air movement to air drying. Screens are placed in front of openings to prevent flies, other insects and birds from entering. If drying is too fast, a crust will form on the outside of the ham and if it is done too quick, the inside will not be dried and will spoil. If drying is done too long, the meat will be too dry to accommodate the lactic acid bacteria which will be involved in the fermentation process.

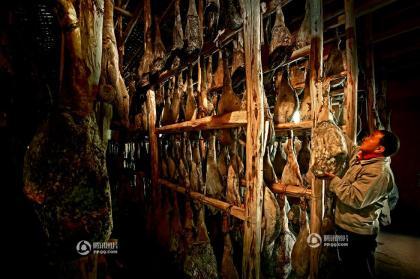

Li Yingqing and Guo Anfei reports on the traditional way that drying was done. “If you visit the villages by Nujiang, you may chance upon a strange sight in winter, when the hams are hoisted high on trees so they can catch the best of the drying winds. These trees with hocks of ham hanging from them seem to bear strange fruit indeed.”

Fermentation

Drying and Fermentation: China on the Way.

After drying, the temperature is raised to 25 deg C. Relative humidity is pushed up to 70% and ideal conditions are created for fermentation. This process lasts for 180 days. Apart from creating an ideal condition for microbes, raising the temperature and humidity favours enzymatic activity, which is important in flavour development due to the partial decomposition of lipids (fat) and proteins. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

Traditionally, the fermentation process takes more than ten months. When the surface is completely green, the hams are ready: China on the Way.

Aging

“Xuanwei ham is like good wine: the older the better. A ham that’s been aged at least 3 years can be eaten raw like prosciutto di parma.”

Control of Pests

During the curing and drying stages, flies pose a major risk. During fermentation and storage ham moths and mites (eg. tyrophagus putrescentiae) are the major danger. Relative humidity of over 80% attracts flies such as Piophila casei, Dermestes carnivorus beetle and mites. “There has been considerable work done in controlling mite infestation. Microorganisms such as the Streptomyces strain s-368 help prevent and treat mite investigation.” (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

Evaluation

Bone needles or bamboo needles are used to insert it into three specific sites to check the ham. The smell tells the evaluator if the ham is ready: China on the Way.

Xuanwei hams are evaluated by sensory evaluation. The odor is absorbed by a bamboo stick, used for the evaluation. This is the most traditional absorption method to classify different ham grades. For a detailed discussion and evaluation of this method, see Xia, et. al (2017), Categorization of Chinese Dry-Cured Ham Based on Three Sticks Method by Multiple Sensory Techniques

Storage

Storage is done under ambient conditions and the hams can be stored between 2 and 3 years.

A caravan travelling along an ancient road. Pu Zaiting must have been driving just such a caravan, journeying from north and south: China on the Way.

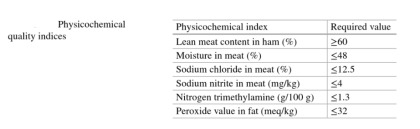

Physiochemical Indices

by Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016

“The physical and chemical properties of dry-cured ham are important determinants of its quality (Jiang et al. 1990 ; Careri et al. 1993 ). The lean portion of Xuanwei ham contains 30.4 % protein, 10.9 % fat, 10.3 % amino acids, 42.2 % moisture, and 8.8 % salt (Jiang et al. 1990 ). The whole ham contains 17.6 % protein, 29.1 % fat, 5.6 % amino acids, 24.8 % moisture, and 3.3 % salt (Jiang et al. 1990 ). Many essential elements are present in the ham as are some vitamins. The ham is particularly rich in vitamin E (45 mg/100 g). The characteristic bright red color of Xuanwei ham is mainly attributed to oxymyoglobin and myoglobin. The flavor and taste are associated with the presence of various amino acids and volatile organic compounds . The volatile substances present in Xuanwei ham have been extensively studied (Qiao and Ma 2004 ; Yao et al. 2004 ). Seventy-five compounds were tentatively identified in the volatile fraction. The compounds identified included hydrocarbons, alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, organic acids, esters, and other unspecified compounds.” (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

Microflora

The dominant microorganism on the surface of dry cured hams is mold, which affects quality. During the ripening stage, molds play an important and positive role in flavour and appearance. A study of Iberian dry-cured hams showed that yeasts are predominant during the end of the maturing phase of production whereas Staphylococcus and Micrococcus are absent. This surface yeast population has been shown to be useful for estimating the progress of maturation. Its contribution to curing is suggested to be their proteolytic or lipolytic activity. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

In Xuanwei hams, researchers have shown Streptomyces bacteria to dominate and account for almost half of the Actinomycetes. Aspergilli and Penicillia are common on the surface of Xuanwei hams during June to August. They found 8 species of Aspergillus. A. fumigatus was found to be dominant and accounts for one third of Aspergilli. Generally speaking, a high relative humidity encourages mold development on the surface of the hams. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

The dominant fungi found on Xuanwei hams is yeast. Yeast can be 50% of the total microorganisms found on mature dry-cured hams. Proteolytic and lipolytic activity of yeast is desirable. Towards the end of maturation, yeast dominates on dry-cured hams. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

Which species to be found during the different stages of production depends on temperature and relative humidity. In the Xuanwei region, humidity and temperature are highest during the rainy season. Molds occur almost exclusively on the surface of the hams. Aspergilli and Penicillia occur mostly during May when relative humidity and temperature are high. These fungi peak in July and August. Molds begin to grow in May and are well established by June. Spores are formed in August and September. The quantity of spores falls off gradually in September. (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

“The growth of bacteria and Actinomycetes does not seem to be dependent on humidity in the curing room. Levels of bacteria are generally lower than levels of yeast. According to Wang, et al. (2006) yeast on ham multiplies exponentially from the beginning of the salting stage to reach a peak in April, and then the numbers drop and stabilise to around 2 x 107 cfu/g.Yeast levels within the ham show similar variation as the surface yeast. According to Wang et al. (2006) yeast accounts for 60 to 70% of the total microbial population on the surface of the ham. In some cases, no molds have been found growing on the surface of good-quality ham; therefore, some researchers believe that molds do not play a direct role in determining the quality of dry-cured ham, but an opposing view also prevails.” (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

“According to the traditional view, high quality Xuanwei ham must have “green growth” (i.e. molds) on it. However, fungi such as Penicillia , Fusarium , and Aspergilli are known to produce mycotoxin in foods such as dry-cured Iberian ham (Núñez et al. 1996 ; Cvetnić and Pepeljnjak 1997 ; Brera et al. 1998 ; Erdogan et al. 2003 ). More than 15 % of the mold strains examined were found to produce mycotoxins in Xuanwei ham (Wang et al. 2006 ). The toxins penetrated to a depth of 0.6 cm in the ham muscle. Because most of the fungi that occur on ham have not been examined for producing mycotoxins , contamination with toxins might be more prevalent than is realized.” (Kristbergsson and Oliveira, 2016)

Feasting

“The ham must be flame burned and washed before eating, in order to remove the rancid taste.” (China on the Way.)

Flame treatment: China on the Way.

There are an infinite variety of ways to serve the ham. It can be steamed, boiled, fried, or used as accessories. Old legs can be eaten raw. When cooking, cook either the whole ham or large cuts on a slow fire or slow boil it to retain the flavour.

China on the Way.

Further Reading

Traditional Foods, Kristbergsson, K., Oliveira

—————————————————————–

Reference

Adshead, S. A. M.. 1992. Salt and Civilization. Palgrave.

chinadaily.com Updated: June 26, 2019

China on the Way, XuanWei Ham

Flad, R., Zhu, J., Wang, C., Chen, P., von Falkenhausen, L., Sun, Z., & Li, S. (2005). Archaeological and chemical evidence for early salt production in China. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(35), 12618–12622. http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0502985102

Huang, Christy. 2015. Old Towns of Yunnan, Heijing.

Kristbergsson, K., Oliveira, J. (Editors). 2016. Traditional Foods: General and Consumer Aspects. Springer.

Mew, T. W., Brar, D. S., Peng, S., Dawe, D., Hardy. B. (Editors). 2003. Rice Science: Innovations and Impact for Livelihood. International Rice Institute (IRRI).

Needham, J., Ping-Yu, H., Gwei-Djen, L.. 1980. Sivin, N.. Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology. Cambridge University Press.

SBS – http://www.sbs.com.au/food/article/2017/04/30/over-1000-years-ham-heres-where-it-all-began

http://www.yunnanadventure.com/index.php/Attraction/show/id/153.html

https://yunnan.chinadaily.com.cn/2012-01/16/content_14500704.htm

http://www.chinaontheway.com/xuanwei-ham/?i=1

Xia, D., Zhang, D. N., Gao, S. T., Cheng, L., Li, N., Zheng, F. P., Liu, Y.. 2017. Categorization of Chinese Dry-Cured Ham Based on Three Sticks Method by Multiple Sensory Techniques Volume 2017, ID 1701756 https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/1701756

Yunnan Xuanwei Ham (宣威火腿/xuān wēi huó tuǐ) Yunnan Xuanwei Ham (宣威火腿/xuān wēi huó tuǐ) Eben van Tonder 10 May 2020 Introduction Yunnan is one of China's premium food regions known for exquisite tastes.

0 notes

Text

Historical Receptions: Why have depictions of lions changed over time?

In early Chinese culture the lion was seen as a divine and mythical beast. These earlier depictions were fanciful, often blended with other animalistic features. This hybridity is evident with the Qilin; a one horned, scaly, hoofed beast with the head and mane of a lion.

Live lions and lion pelts were traded along the silk road from c. 114 BC. Lions were a highly sought-after and rare commodity with only the very wealthy being able to afford live specimens. Most of these ended up in private estates. With access to lions being limited to an elite few, many artists had to rely on copying from earlier, imaginative representations.

Although still an expensive commodity, the sight of pelts may have been more common. Transporting a cart full of pelts would have been a considerably easier task than the transportation of one live lion over such a distance. Pelts however, display lions in a flattened form, they cannot convey its muscular tonality nor its posture, this may have been one cause of artistic misrepresentation.

A gradual change in the tradition can be observed by comparing depictions of lions during the Han (206BC-220AD) and Tang (618-907AD) Dynasty’s. The later Tang period having more realistic portrayals by artists and artisans, who, presumably, had more opportunity to observe the animal first-hand after centuries of lions being transported into the country. This could possibly provide one explanation as to why it took Chinese artists several centuries to formalise the appearance of lions. However, whilst later depictions eschewed the fantastical elements, the lion remained heavily stylised. The longevity of the tradition and the lion’s religious connotations were already heavily integrated into the Chinese culture as recognisable forms of ‘symbolic capital’ (Bourdieu, 1979), possibly surpassing eventual competency for mimetic accuracy through accessibility.

The relationship between the ‘lion’ and ‘stone’ is connected to the common Chinese tradition of using puns and word play to group or associate objects. The word for lion and stone is the same, Shi, the only difference being the phonetic stress on each word, Shíshī. This relationship between object and material is evident within its long historical association. Lions being used as ‘stone guardians’ to tombs, pre-dates the first records of live lions arriving in China.

Comparing Western sculptures of lions to Chinese examples from the same era highlights this aesthetic difference. Chinese depictions portrayed lions as symbolic in opposition to Western mimesis. Interestingly, the influence of Chinese sculpture can also be observed in the Western statues, where the lion also has a ball under its paw. The Romans were masters of cultural appropriation and it is more than likely that they ‘borrowed’ this feature from their Eastern trade partners. In China this ball symbolises that this lion is male and its spiritual qualities. The ball under the foot of this Roman example, the famous ‘Medici Lion – c. 2AD’ has a very ambiguous explanation on its Wikipedia page, ‘a ball, possibly a globe’, the ball has no meaning in Western culture. Foucault describes this phenomenon as ‘repeatable materiality’ where statements and symbols from one culture can be reinterpreted and transcribed in the discourse of another.

Medici Lion (Rome):

Guard Lion (China):

0 notes

Text

Tea 101: Origination Part 1 The Legends

"Tea has a long and turbulent history, filled with intrigue, adventure, fortune gained and lost, embargoes, drugs, taxation, smugglers, war, revolution, religious aestheticism, artistic expression, and social change." Mary Lou & Robert J. Heiss (The Story of Tea)

The history of tea is slippery. Its origin stories are street-wise and nimble; nailing down a single tale feels a bit like unravelling knotted necklace chains, coiled together at the bottom of your suitcase. The rich history of tea is multi-storied, but I've sifted out two to get us started.

In the beginning...

The Legend of ShenNong (2737 BC)

Once upon a (prehistoric) time, in a land far far away (unless you are in China) lived the legendary deity, Shennong. Shennong was a mythical sage ruler, and the mastermind behind Chinese agriculture and medicine. One windy day, he was drinking a bowl of boiled water (all the subjects of the land cleansed their water by boiling it first) and a few leaves blew into the cup, changing the colour. The emperor took a sip of the brew, and was pleasantly surprised by its flavour. Some tell a variant of the legend, in which Shennong tested the medicinal properties of teas on himself, and found them to soothe ailments and work as an antidote to poisonous herbs. (For more on this legend and others, check out Lu Yu's famous early work on the subject, The Classic of Tea.)

The Legend of Bodhidarma (Tang Dynasty 618 - 907AD)

*sometimes, another version of the story is told with Gautama Buddha in place of Bodhidharma.

Bodhidharma was a Buddhist monk who lived during the 5th or 6th century. He is traditionally credited as the transmitter of Chan Buddhism to China. According to Chinese legend, he also began the physical training of the monks of Shaolin Monastery, which led to the creation of Shaolin kungfu. In Japan, he is known as Daruma. The rather gruesome legend dates back to the Tang Dynasty. In the traditional folklore, Bodhidharma accidentally fell asleep after meditating in front of a wall for nine years. He woke up in such disgust at his weakness, that he cut off his own eyelids. They fell to the ground and took root, growing into tea bushes. This myth expresses the sentiment that tea is the drink of woke-folks: open eyes as a metaphor for staying present, engaged, and aware in the world.

So there you have it, the first two pieces of a tea leaf puzzle. Origin stories shape our collective consciousness, and function as a container for growing. Share below if you know another version of the tale!

Much love and tea-stained fingertips,

Vanessa

0 notes

Text

[Hanfu · 漢服]Time Clothes·Wu Zetian【时裳•武则天】·Early Tang Dynasty

----------

【Summary】

In this 180-second video, shows the fashion trend of Wu Zetian's life, the first fashion change led by women in China, from simplicity to luxury, from conservative to open, from restraint to freedom, this video is not only to show the beauty of Hanfu, but also to show A changing era in Tang Dynasty.

Wu Zetian(武则天), the only female emperor in China, experienced one of the fastest changing periods in the history of Chinese fashion in her life. As the woman who finally reached the top, she also had a huge leading influence on the trend of the Tang Dynasty at that time.

"Time Clothes·Wu Zetian", through the cultural relics and image reproductions of the same period in the collections of Luoyang Museum, Luoyang Archaeological Research Institute, and Yanshi Shangcheng Museum, sorts out the fashion development of Wu Zetian(武则天) throughout her life.

-------------

【637-649 A.D.】武家有女 初入宫掖 In 637, when Wu Zetian was fourteen years old (November of the eleventh year of Zhenguan, because of her beauty, she was selected as the emperor's consort, and was named a fifth-rank "才人/Talented Lady". Emperor Taizong bestowed on her the title call"Wu Mei/武媚".

At that time, the clothing followed the Sui Dynasty system, which was conservative and frugal.Women in the early Tang Dynasty dressed conservatively, with higher necklines and skirts. Women need to wear "mili/幂离" (a kind of hat, surrounded by a circle of gauze that reaches the feet) to cover the whole body, so that passers-by cannot see the woman's face. During the Emperor Taizong period, frugality was advocated, and court women's clothing used less brocade, and only a small amount of brocade was used on the edge of the sleeves.Women wear a hairstyle called "panhuanji/盘桓髻", wear skirts up to the armpits, narrow sleeves and short shirts, and wear "bapojian skirts/八破间裙 (a skirt sewn with different colored fabrics)"

【651-664 A.D.】高宗即位 再入宫廷 When Emperor Taizong died in 649, his youngest son, Li Zhi, whose mother was the main wife Wende, succeeded him as Emperor Gaozong. Li Zhi had had an affair with Wu Zetian when Taizong was still alive.Taizong had 14 sons, including three by his beloved Empress Zhangsun (601–636), but none with Consort Wu.Thus, according to the custom by which consorts of deceased emperors who had not produced children were permanently confined to a monastic institution after the emperor's death, Wu was consigned to Ganye Temple (感業寺) with the expectation that she would serve as a Buddhist nun there for the remainder of her life. But Wu defied expectations and left the convent for an alternative life. After Taizong's death, Li Zhi came to visit her and, finding her more beautiful, intelligent, and intriguing than before, decided to bring her back as his own concubine.

During this period, the aesthetics of the Tang Dynasty began to change, from thin to tall and straight.The social atmosphere is gradually opening up, and women's skirts are moved down to the bust line.Wider cuffs and collars, tall half-up hair buns and various ring shape hairstyles are the most popular hairstyles.

【664-689 A.D.】天后掌权 二圣临朝

By early 650, Consort Wu was a concubine of Emperor Gaozong, and had the title Zhaoyi (昭儀) (the highest-ranking of the nine concubines in the second rank). She progressed rapidly, earning the title of huanghou (皇后) (empress consort, the highest rank and position a woman held in the empire), and gradually gained immeasurable influence and unprecedented authority over the empire's governance throughout Gaozong's reign. Over time, she came to control most major and key decisions made during Gaozong's reign, and presided over imperial gatherings.

Women's political status gradually improved with the power gained by Wu Zetian, and women's dress styles developed in a gorgeous, confident, and open direction.During this period, China's weaving technology developed rapidly, and various brocade patterns of "Da Ke Baohua Brocade/大窠宝华织锦" with larger sizes appeared and were more widely used in the palace.

【690-700A.D.】武皇登基 女性天下

In 690, Wu Zetian had Emperor Ruizong yield the throne to her and established the Zhou dynasty, with herself as the imperial ruler (皇帝).She allowing women to participate in politics, the image of women is moving towards the most confident, plump and calm era in ancient Chinese history.

The clothing materials of women in the upper class are becoming more and more extravagant, with half-sleeves/半袖 and magnificent brocade patterns on the Beizi/背子. A double spiral hairstyle, and the skirt is further moved down.

【700-705A.D.】称制十年 女性觉醒

In the late period of Wu Zetian's reign and even after she was forced to abdicate, many female politicians continued to lead the fashion of dressing, and more open and exaggerated dressing styles became popular.

The collar of the jacket is mainly turned into a cross-collar, and the short sleeves of the jacket are no longer tucked into the skirt, which greatly increases the exposure of the skin.Comb the hairstyle in the shape of "big knife" on the head call “大单刀髻”,ornately embroidered shawl,cross collar and half sleeve,top that covers the skirt

————————

📸Video: @扬眉剑舞

Model :@荷里寒

Plan: @洛阳博物馆1958 & @扬眉剑舞 &@同程旅行官方微博

🔗Weibo:https://weibo.com/1879589532/NfEFEkRHY

————————

#chinese hanfu#Tang Dynasty(618–907AD)#Early Tang#wu zetian#hanfu#hanfu accessories#hanfu_challenge#chinese traditional clothing#china#chinese#china history#tang fashion#life of wuzetian#漢服#汉服#hanfu history#historical fashion#woman emperor

235 notes

·

View notes

Photo

【Historical Artifacts Reference】

Murals in the Tomb of Princess Xin Chang, Liquan County, Shaanxi Province/陕西省礼泉县新城长公主墓壁画 (663 AD)

[Hanfu · 漢服]Chinese Tang Dynasty (618–907AD) Traditional Clothing Hanfu & Hairstyle Based On Relics Murals in the Tomb of Tang Princess Xin Chang

Women’s Clothing, Hairstyle in the Early Tang Dynasty Period (663 AD)

—————-

【History Note】

After the establishment of the Tang Dynasty, with the completion of the great unification and the recovery of the social economy, the stable status of a big country brought a confident and enlightened cultural atmosphere, which was fully reflected in clothing and social customs.

At that time, all the noble ladies in the palace liked towering hairstyles, and advocating slender clothing was the fashion, showing a tall and elegant temperament as a whole. In such popular aesthetics, the combination of high buns and inter-color skirt became all the rage and became a representative attire in the early Tang Dynasty.

In addition, the makeup gradually deviates from the relatively plain style in the past, and develops into more gorgeousness. The red makeup that put on the cheeks becomes thicker and the range gradually expands. The shape of eyebrows has changed from slender eyebrows to bold thick eyebrows, and face decorations such as Huadian(花钿) and XieHong斜红() are also more prominent.

※ Huadian(花钿) :traditional Chinese ornamental forehead makeup

※ XieHong (斜红) : a special kind of face decoration in ancient times. When dressing up, a red crescent is drawn on both sides of a woman’s eyes.

In this set of attire, the model hair in a double bun, wears a narrow-sleeved blouse with brocade margins on the inside, half-sleeves with brocade margins on the outside, and a inter-color skirt,a light gauze wrap around her body. It was a popular dress in the Tang Palace during this period.

On the occasion of the Spring Festival, 裝束复原 Team wishes more people get to know about the traditional Chinese costume culture. At the same time, wish every friends around the world have a happy New Year!

————————

Recreation Work: @裝束复原 & @桑纈

🔗Weibo:https://weibo.com/1656910125/Mpl9wlxE5

————————

#Chinese Hanfu#Tang Dynasty (618–907AD)#Hanfu#Early Tang Dynasty Period (663 AD)#Tomb of Tang Princess Xin Chang#hanfu history#chinese history#china history#Chinese historical fashion#historical makeup#historical fashion#chinese traditional clothing#chinese#chinese new year#spring festival#Chinese Culture#recreation#chinese art#Chinese Aesthetics#chinese fashion history#裝束复原#桑纈#Huadian(花钿)#XieHong (斜红)#shanqun#pibo#间色裙 (inter-color skirts)#漢服#汉服

306 notes

·

View notes

Text

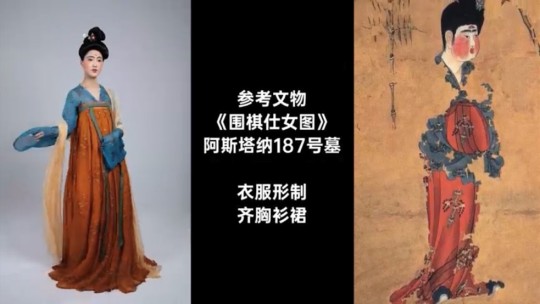

[Hanfu · 漢服]Chinese Tang Dynasty(618–907AD)Traditional Clothing Hanfu Based On Stone Carving of Tang Dynasty

The image of girls in the early Kaiyuan reign (713-741) of the Tang Dynasty

【Historical Artifact Reference】:

China Tang Dynasty Stone carvings on the stone coffin of Xue Jing(薛儆)'s tomb

Xue Jing(薛儆):son-in-law of Emperor Ruizong of Tang China

————————

📸Recreation Work &🧚🏻 Model :@-盥薇-

👗Hanfu:@香染衣罗传统服饰

🔗 Weibo:https://weibo.com/3942003133/OzQ3S2h4x?refer_flag=1001030103_

————————

#chinese hanfu#Tang Dynasty(618–907AD)#hanfu#hanfu accessories#hanfu_challenge#china#chinese traditional clothing#chinese#漢服#汉服#中華風#chinese style#chinese history#chinese fashion

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

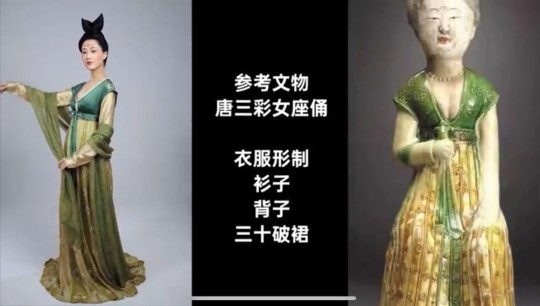

[Hanfu · 漢服]Chinese Early Tang Dynasty (618–907AD) Traditional Clothing Hanfu Based On Tang Dynasty Figurines

【Historical Reference Artifacts】:

▶ China Tang Dynasty Figurine:

1.<Tang Dynasty female figurines head,Collection of Tokyo National Museum>

2.<Female Painted figurine with "Sling Bag"/"挎包"彩绘俑,China Luoyang Museum Collection>

3.<FPurple square check pattern damask curtain hat/紫地方格纹回纹绫帷帽,Qinghai Provincial Museum Collection>

————————

📸Recreation Work &🧚🏻 Model :@吃货娃娃

👒Hat:@栗盐

🔗 Weibo:https://weibo.com/1868003212/NspThiP7E

————————

#chinese hanfu#Tang Dynasty (618–907AD)#hanfu#chinese traditional clothing#hanfu accessories#chinese#china#hanfu_challenge#chinese history#hanfu history#hanfu girl#chinese art#漢服#汉服#中華風#chinese style#吃货娃娃

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

【Historical Reference Artifacts】:

China Tang Dynasty Lotus Crown Female Figurines,Collection of Xi'an Museum

China Tang Dynasty Murals from Prince of Ning Li Xian(李憲)Tomb Mural (742)

[Hanfu · 漢服]Chinese Tang Dynasty(618–907AD) Traditional Clothing Hanfu & Hairstyle Reference to Tang Dynasty Figurines

【History Note】

Wearing a lotus crown is a symbol of Taoism.Until now, Taoists still wear lotus crowns when performing Rituals and only high-level Taoist priests can wear lotus crowns.

Generally, the Taoist priests we see are all male, so many people will misunderstand that Taoist priests can only be male, but this is a wrong statement.

As early as the Jin Dynasty(266–420), the first female Taoist priest appeared: 【Wei Huacun 魏华存】。

Wei was born in 252 in Jining, Shandong in the former county of Rencheng (任城). Her father, Wei Shu (魏舒), was a government official. From an early age she displayed a propensity for studying the works of Laozi and Zhuangzi, and practising Daoist methods of cultivation.

At the age of 24, she was married to Liu Wen (劉文) against her will by her parents and had two sons. After they grew up, she resumed her Daoist practices. At some point she became a libationer in the priesthood of the Celestial Masters sect of Daoism.

Except Wei Huacun, one of the four beauties in China, Tang Dynasty beauty: [Yang Guifei杨贵妃/Yang Yuhuan杨玉环] also used to be a Taoist priest for a while.Her Taoist nun name is Taizhen (太真).

Therefore, it is speculated that she was also wearing a lotus crown when she was a Taoist priest.

In the middle and late Tang Dynasty, lotus crowns were not only worn by female Taoist priests, but ordinary women also liked to wear them. Until the Song Dynasty, the crown worn by women were not limited to the shape of the lotus, and even the material changed, such as: ivory, jade,and so on.

—————————–

🧚🏻Recreation Work: @我是411

🌸Lotus Crown:@时春居荷包

👗Hanfu:@墨名堂的箱掌柜

🔗Weibo:https://weibo.com/2040114485/N7EPOiEHN

—————————–

#chinese hanfu#Tang Dynasty(618–907AD)#hanfu#chinese traditional clothing#hanfu accessories#hanfu_challenge#chinese#chinese history#Taoism#female Taoist priests#lotus crown#china#historical fashion#historical hairstyle#chinese fashion#我是411#时春居荷包#墨名堂的箱掌柜

166 notes

·

View notes