#ESPECIALLY !!! since one of the things that the authors talk about is how rubrics in general are a useful way of standardizing grading

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

accidentally getting a little too into my pedagogy class and starting to wonder if I should pivot and go into education (academic field)

#from the writer's den#void talks#not me seeing a paper on co-constructed rubrics as a potentially more positive route for writing assignments and pogging a little..........#I'd be embarrassed but it was actually a really interesting read#and at multiple points while reading I was like wow I would love to try this in class as part of Contributing To The Science#like deadass...#specifically for creative writing I would be interested in merging it a bit with the stuff in the anti-racist writing workshop (book title)#about collaboratively defining craft terms with students as a means of community building#like that'd be interesting to look at! rubrics shmubrics frankly I don't think they have a place in creative writing but like#if we expand it to thinking generally about assessment--which is inevitable in any credit-giving class--I think it applies#ESPECIALLY !!! since one of the things that the authors talk about is how rubrics in general are a useful way of standardizing grading#and guess what !! non-standardized grading is also a big issue when it comes to equalizing across race class etc#so like genuinely I think there's something there#and I would love to do a little study on it#frankly I might just do so since I'll be teaching next year and have basically free book on course design#at very least will be keeping this in mind for later in the semester when we'll be talking about assessment#but anyway. marge meme (holds up the field of education studies) I just think it's neat#and I have so much respect for it

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

do you have any tips on how to start writing fics?

the outsiders brainrot actually has me coming up with ideas and i have a desire to start writing them into actual stories but i've never written outside of class papers/assignments and i don't really know where/how to start since it's all just my own prompts and ideas and there's no grading rubric lmaoooo

like do you plan out each fic with a list first or do you just start writing about the main plot point of the chapter and fill in around that out of order or do you just start writing and see where it takes you...

how do i know when to stop writing or decide on which endings/paths/plot points to go with... the deadly combo of indecisiveness and perfectionism along with having no guidelines or due dates is crippling me so im asking some of my fav authors (who have also been inspiring me to write and be creative)

OMG HI! I love talking about writing so buckle up.

First of all, starting creative writing is hard, especially when you haven't done it before. Heck, I struggle with it so much! For me there are two places I start from:

A moment or visual

When I'm writing a short fic, I don't plan them out, I just start writing and see what comes out. I'm not sure if you noticed, but most of my fics start and take place at night. That is because a visual that really sticks in my head is streetlights coming through windows or a light in a dark room.

I would recommend thinking of a visual you're drawn to or a feeling you want to capture. Start there and then build on the scene.

If that doesn't work for you, think about what you're trying to capture in the story. What character are you focusing on? What aspect of the character? And then start with that character's thoughts or maybe a flashback that leads into the point you're trying to make.

The plot

Right now, I've been writing a lot of one shots, but I really want to write a multi-chapter fic for the outsiders soon! This is the process I use for that.

I always do an outline when writing longer fics, it helps me figure out where the story is and where it needs to go and how long I have to get it there. Here's an example of what my outlines look like, I do one for each chapter.

Chapter 4 Korrin being more fatherly to Vax (big feelings) Vax finds Simon Vax’s backstory reveal (where’s Vex?) Leads to issues with the actual alliance because they find out it’s not recognized by Syngorn Hair braiding First time sharing a bed (v soft)

These are key moments I want in each chapter and the emotional and plot stakes.

And then there's the question of where to end. It's hard, I mean half the time I just end it when it feels right, but I know that's not helpful.

I would say that you should end the story when everything that needs to be achieved One of my biggest pet peeves with fanfic is people ending the stories before they're finished. And I know that it's an artistic choice sometimes, but personally I don't like it lmaooo.

Creative writing is hard as hell. I've been doing it since I was eight and it is still a struggle. When you write, let the story tell you where it wants to go. Sometimes that means it's completely different from what you started with and that's a good thing!

But all in all, don't be discouraged. It takes time to get started, but you should know that I've only been writing Outsiders fics for a month or two and everyone has been so kind and welcoming <3

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

something will always fill a vacuum

(reposted, with edits, from Twitter)

Okay, let's talk about why attempts to critique (or hell, straight up stick it to) Christianity in SFF often end up being more anti-Jewish than they are anti-Christian.

This was inspired by Jay Kristoff's work, which manages to evoke a whole bunch of antisemitic medieval tropes AND, as a bonus, even shits on the name "Ashkenazi", which is the Jewish term for most European Jews. But the thing is, Kristoff's SO antisemitic that I don't think it's accidental. I'm more interested in how it happens out of ignorance rather than malice.

So, negative evocations of Christianity in SFF usually fall into one or more of three categories:

allegories for/evocations of the Inquisition

allegories for/evocations of witch hunts

Christianity without Jesus

I suspect there are also plenty of evocations of the Crusades out there, especially in SFF by non-Western authors, but I haven't seen it nearly as much. I want to be clear that these aren't usually discrete uses of these tropes. They usually blend together. Evocations of the Inquisition usually have evocations of later witch-hunts as well, and it's almost always Christianity Without Jesus.

I'm generally fine with using the Inquisition and the witch hunts as models for fictionalized versions of the church as a force for evil. They were Christianity as a force for evil in real life.

But they're often clearly written by people who haven't actually studied the periods in question before using them as a model--the Salem "witches," for example, were Christians, and not just women, and targeted more for financial reasons than religious ones. (Also, they weren’t burned at the stake, for crying out loud. You’re not the granddaughters of the witches they couldn’t burn. Like every word of that slogan is wrong.) But honestly, whatever. I’m not interested in holding fantasy to historical accuracy.

It's the way Evil Christianity Analogues are generally missing a Jesus figure that starts to make them problematic.

Much of the world's perception of Jews and Judaism is basically "it's like Christianity but without Jesus."

Attempts to portray Christianity Analogues as bloodthirsty and primitive generally assume that what's "primitive" is what's older.

They tend to distrust ritual, and portray ritual either as primitive superstition, or as a facade that the Evil Priests use to manipulate the Naive Villagers.

And you may think you're sticking it to Christianity by doing your fic with evil Inquisitors who burn witches, but when a hallmark of its evil is that there's no Jesus analogue, you're actually not sticking it to Christianity. You're reinforcing its supremacy.

Or put another way, the idea that if you remove Jesus, Christianity becomes evil is just the flipside of "REAL Christianity is inherently good."

If you're going to have masses and priests and Inquisitors and witch burnings and all the other specific trappings of actual Christianity, put a fucking Jesus analogue in there. Because it's not "religion", it's SPECIFICALLY THE RELIGION THAT WORSHIPS JESUS, that did all these things.

Cultural practices are not an equation

A lot of this comes from a very old anti-Jewish trope: the OT God=vengeful, NT God=loving rubric.

Now, I'm not going to spend a lot of time debunking that trope in this thread, other than to say that every single loving- or compassionate-sounding thing Jesus ever said is literally a quote or paraphrase from the Tanakh.

Yet there's a long-standing idea in pop culture Christianity that the problem with Christianity is the “Old Testament.” You hear it ALL THE FUCKING TIME on TV. Some bigoted Christian character quotes something from the OT and the hero says something like, "we've had a whole other testament since then."

So, the idea that if you do Christianity without Jesus, you get Bloodthirsty Old Testament Religion is a huge trope in...

<drum roll>

...Christian depictions of Satanism.

You know what I'm talking about, yes? Satanism as portrayed by Christians is missing Jesus, and usually involves a lot of animal sacrifice, and then human sacrifice, and often a smattering of Hebrew, that Ancient And Alien Language. Or sometimes Aramaic. (I could do a whole post about how weird Christians are about Hebrew and Aramaic.) So Satanism as imagined by Christians is intended to be a dark mirror of Christianity, and there are elements of that, in that there's usually elements from Catholic mass, usually some Latin.

But in essence, what they're creating is Ancient Evil Religion Without Jesus, which ends up looking a lot like what they tend to think Judaism looks like, or looked like back in the day. (Without the "Evil", of course, or at least without saying it out loud.)

animal sacrifice, which Jesus negated the need for

Hebrew as an ancient powerful magical alien language, rather than as, I dunno, the language of real people?

a vengeful and bloodthirsty deity figure, without a mediating savior

(BTW, I and plenty of other Jews I know have been asked, by apparently well-meaning Christians, how we handle sacrificing animals in contemporary America. I’m sure that if this post gets any traction, a bunch of Christians are going to respond that they know we don’t actually practice animal sacrifice and let me just go ahead and give you your gold star and your cookie and please note the giant eye roll accompanying said cookie and star.)

A little detour into the Satanic Panic

The attitude toward imagined Satanism, with its ritual and its sacrifice and its churchiness, looks a little different whether you're getting it from Catholics or Protestants.

With Catholics, it's "this is a mockery of the mass, which is why it's ritualized"

With Protestants, With Protestants, you get something a lot uglier. It’s “our Christianity is fresh and organic and flexible and real and just about a genuine relationship with God,” opposed to ancient, heartless, primitive, ignorant ritual like that in Satanism and Judaism and Catholicism

And of course, when actual Satanism as a practice became a thing, and not just a bogeyman in the fevered imaginings of paranoid Christians, it was primarily as a way to troll Christians. But it also pulled in a lot of really ugly white supremacist Victorian ideas about the occult.

It didn't start from what could we do to create a practice that actually highlights everything that's wrong with Christianity. You know, an actual satire of it. It mostly started with performing what Christians thought Satanism would look like. Trolling, as opposed to critique. It’s evolved since then and developed more into its own thing, and the point of this post has nothing to do with practicing Satanists, so I’m going to leave it there--this is just to point out that Satanism, full stop, both imagined and real, has always been something that exists inside Christianity, and is nonsensical outside/without Christianity.

So again, and I can't emphasize this enough: What Christians think actual Satanism would look like isn't a critique of Christianity. It's a reification of it. It's self-congratulatory. The Christian idea of Satanism exists only to enforce the “correctness” of Christianity.

You can see this because--edgelordery among heavy metal artists and edgy teenagers notwithstanding--there's nothing actually attractive about Christian depictions of Satanism. No one seems to be having any fun. There's no there there. I mean, Michelle Remembers, The Satan Seller, Rosemary’s Baby, Go Ask Alice, Satan’s Underground, The Omen, Eye of the Devil--in all the famous texts of the Satanic Panic, it’s remarkable how unpleasant and dreary Satanic practices seem to be. It’s hard to imagine anyone finding these practices enjoyable or rewarding. There’s a typical authoritarian Christian lack of curiosity about humans’ inner lives in these portrayals: no one’s asking why anyone would want to engage in these practices. It’s just some people are evil, end of story.

The entire point of Satanism in the Satanic Panic is to make Christianity look good.

It exists, in their imaginings, solely to mock Christian ritual, but like, no one actually wants to eat a host made of feces? No one wants to have unpleasant and ungratifying sex? It's just misery for misery's sake, which is what Christians panicking about Satanism apparently imagine non-Christianity to be.

Back to fictional Evil Churches

So when SFF authors/game devs/whoever want to worldbuild a fictional evil church, somehow it usually ends up being Christianity with a very conspicuously missing Jesus.

Obviously, a comprehensive survey is beyond the scope of this Tumblr post, but here are a few examples:

Shin Megami Tensei literally has a church that worships “YHVH,” an explicitly evil god. There’s no Jesus analogue.

The Church of Tal in Magic: The Gathering is full of hypocritical inquisitors who persecute magic users while using magic themselves. This is pretty obviously a dig at evangelicals who claimed M:TG was satanic in the 80s and 90s, but again, weirdly, no Jesus.

Final Fantasy X has the Church of Yu-Yevon, which of course turns out to be Bad. No Jesus.

Dishonored is an interesting example, since the Abbey of the Everyman doesn’t have a god--or rather, it’s designed to protect people from its god, the Outsider. But it’s got all the tropes of churchiness and the Inquisition, and of course, no Jesus.

The Deep Church in Dark Souls.

The Chantry in Dragon Age isn’t straight-up evil--they’re a positive force in some ways, but they're also Inquisition-y toward mages and straight-up evil toward the Dalish elves. No Jesus.

Mercedes Lackey’s various fantasy worlds usually have some analogue to Christianity (in the first of the Heralds novels, Talia, the main character, comes from a background that clearly draws from both evangelical Christianity and Amish/Mennonite/etc. tropes). There’s no Jesus analogue.

Hell, in Phillip Pullman’s His Dark Materials, the church is literally a Christian church. Like, it’s not a completely different world; it’s our world but a little different. And yet somehow Jesus is very absent.

David Eddings’ Church in the Elenium and Tamuli series isn’t terrible, exactly, but it bounces back and forth between corrupt and hapless. It’s pretty clearly Fantasy Christianity, right down to the scriptures and the clerical titles and the Vatican infighting and yet, no Jesus.

Terry Pratchett’s Church of Om isn’t wholly evil, but it’s a satire of overly “ritualistic” Christianity--ritual is sterile, ritual is a substitute for true belief--and causes a lot of war. No Jesus, of course.

Brandon Sanderson’s Vorinism arguably rushes right past the accidental antisemitism of “no Jesus makes you evil” into straight-up antisemitism, but that’s a whole other post.

I mean, look, I could make this list really long, especially if I wanted to get into “Evil Religions that do very Christian Inquisition things, but have a pantheon that’s loosely based on the Greeks or whatever,” and how they’re still very much cast in a Christian mold, but never have a Jesus analogue, but we’d be here all day.

If you’re not Christian, why do you think Jesus saved the world?

The point is, a lot of people doing worldbuilding want authoritarian priests and witch-hunting inquisitors and Women Wrecked The World patriarchy and abusive exorcisms of people who aren’t possessed and conversion therapy and all that. Some of them are Big Mad at Christianity, some aren’t, but either way, they believe they have something to say about the harm Christianity has done.

But the real-world people who did all the horrible things Christianity has done weren't practicing Christianity-but-without-Jesus. They were practicing Christianity full stop.

And yes, actual Judaism as practiced by actual alive Jews isn't actually anything that resembles Christianity, with or without Jesus. But the problem is, for most of the world, their understanding of what Judaism is is "basically Christianity, but without Jesus."

When you decide to do an analogue of Christianity to be the evil religion in your SFF/game, but you neglect to include *the central element of Christianity*, which is, you know, Jesus, what you're actually suggesting is that Jesus is the thing that redeems "Abrahamic religion." (BTW, stop using that term since y’all seem to use it to try to blame Jews and Muslims (and by extension, all the other Abrahamic religions that you don’t even seem aware exist) for stuff that is specifically and uniquely Christian.)

So if you think that Jesus is the thing that makes Christianity good, so much that you can’t imagine a Fantasy Evil Christianity Analogue that has a Jesus figure, what does that say about what you think about Jews?

If you're pissed at Christianity, and if you want to create an SFF setting that contains Evil Religion, why can’t you seem to bear to actually include a Jesus figure in your portrayal?

You’re actually reifying the idea that Christianity (”true” Christianity that actually worships Jesus) is uniquely and inherently good, and all the things you see as trappings of it (belief in a single God, ritual, tradition, sacred texts) are bad without Jesus.

So again, unfriendly reminder that the main Abrahamic religion in which Jesus has no place isn’t the one that did all the colonialism and inquisitioning and witch-hunts and swordpoint conversions and Crusades, and isn’t the one currently taking away your reproductive rights and putting torture of LGBTQ kids into law and trying to make it impossible to exist comfortably if you don’t believe as they do.

That’s all been the Jesus-people, not us.

Maybe think about that next time you’re worldbuilding.

82 notes

·

View notes

Note

it seems like a lot of my fave authors have left stucky fandom after a:e which i mean I totally get but it makes me sad. i noticed you have written mostly other stuff for the past couple years than stucky and i wondered if you were going to do anymore, since you said you were maybe writing for the septender thing. I hope so!

I apologize for taking so long to reply to this; it’s been busy and stressful here. And it’s after I posted the Septender challenge fic, so you’ve no doubt seen that I didn’t do Stucky for it, but Steve & Natasha friendship. (I mean, there’s a hint in there of Steve/Bucky being a thing, but that’s all it is.) I haven’t really done a lot of Stucky lately because I kind of struggle with feeling like what’s the point? It doesn’t feel like there’s much in the way of return for a lot of hard work, and it’s easier not to write than it is to write. Which isn’t to say I don’t have Stucky ideas, just not much motivation to do them.

What you’re talking about, though, is kind of a thing we used to call fannish drift, back in the day. It seems like people move on to other things with alarming speed these days, so I imagine that’s a term that’s sort of been lost to another era. People drift away from something, for many reasons, and it can really suck when it’s your favorite authors or vidders or artists and they’ve fallen for something new and shiny, but you’re over there going “but what about our characters!” When I first started in media fandom (which was a rubric used to distinguish it from science fiction and fantasy fandoms or comics, which were the predominant way of being a fan and heavily literature based), there were honestly so few movies and shows with a fannish bent that when someone drifted away, either to a new fandom or other life stuff, it could strongly affect output.

Things kind of exploded in the late ‘80s and into the ‘90s, there were so many more fandoms, that it didn’t have quite the same impact when someone drifted away, but if you were in a small fandom, it could be devastating. Things really went crazy when fandom at large moved to the Internet, and then the powers that be began actively courting fannish types. It’s been an interesting shift to watch happen, but I sometimes think that with so much content, so many people participating, so many modes of expression, it makes it way easier to just wander off to something else.

Fannish drift happens for a lot of reasons—no new canon or becoming disillusioned with canon, like with Avengers; conflicts (I’ve seen some huge emotional conflagrations in my time, or there are issues like bullying/attacking other fans); busyness/life changes (I think this is a big one, especially for women); or just feeling like you’re not valued/don’t fit in in the community. Most of those are things we can’t do anything about, really, they’re just gonna happen.

But that last one, I think, is definitely something you (the generic you, not you in particular, anon!) can do something about. Maybe not to completely stop someone from leaving a fandom, or not keep them writing/drawing/vidding/whatever, but inspiring them to feel like it matters when they produce the content we desire. It’s one reason I always encourage people to leave comments, or reblog posts, or share links, make recs pages, what have you, and why I’m sad that reccing seems to have mostly died off as a fandom thing. The more people see that someone, anyone, cares about the stuff they produce, the better the chances to retain their interest if they’re feeling like their works don’t matter.

Everything moves so fast, and there’s so much content out there. Producers or their content can get lost in the shuffle. I love things like the zero comment challenge or when people rec works that have less than 300 or 500 kudos, or what have you. I love those challenges to leave comments on fanworks, or spread more recs. I’ve loved participating in big bangs and other challenges, because you see all this stuff getting out there in communities. With for-profit spaces taking up most of our fan lives these days, we don’t necessarily have the methods for people to get noticed or it’s harder to feel like you’re part of a community, and that can really affect the enthusiasm to share with fandom those things we work so hard to create.

I realize that’s a huge digressive answer to your comment, but if (generic) you are finding some of your favorite creators drifting away or producing less, I’d always challenge you to make sure those creators know how much you value their work, in case that’s what’s motivating the drift. More feedback for creators (and supporters! I am a huge believer in the idea that there’s no such thing as “just consumers,” we all matter) will only be a good thing, and who knows, it could be the difference between your fave drifiting away or staying in your shared fandom and producing more work.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hong Kong: Anarchists in the Resistance to the Extradition Bill An Interview

Since 1997, when it ceased to be the last major colonial holding of Great Britain, Hong Kong has been a part of the People’s Republic of China, while maintaining a distinct political and legal system. In February, an unpopular bill was introduced that would make it possible to extradite fugitives in Hong Kong to countries that the Hong Kong government has no existing extradition agreements with—including mainland China. On June 9, over a million people took the streets in protest; on June12, protesters engaged in pitched confrontations with police; on June 16, two million people participated in one of the biggest marches in the city’s history. The following interview with an anarchist collective in Hong Kong explores the context of this wave of unrest. Our correspondents draw on over a decade of experience in the previous social movements in an effort to come to terms with the motivations that drive the participants, and elaborate upon the new forms of organization and subjectivation that define this new sequence of struggle.

In the United States, the most recent popular struggles have cohered around resisting Donald Trump and the extreme right. In France, the Gilets Jaunes movement drew anarchists, leftists, and far-right nationalists into the streets against Macron’s centrist government and each other. In Hong Kong, we see a social movement against a state governed by the authoritarian left. What challenges do opponents of capitalism and the state face in this context? How can we outflank nationalists, neoliberals, and pacifists who seek to control and exploit our movements?

As China extends its reach, competing with the United States and European Union for global hegemony, it is important to experiment with models of resistance against the political model it represents, while taking care to prevent neoliberals and reactionaries from capitalizing on popular opposition to the authoritarian left. Anarchists in Hong Kong are uniquely positioned to comment on this.

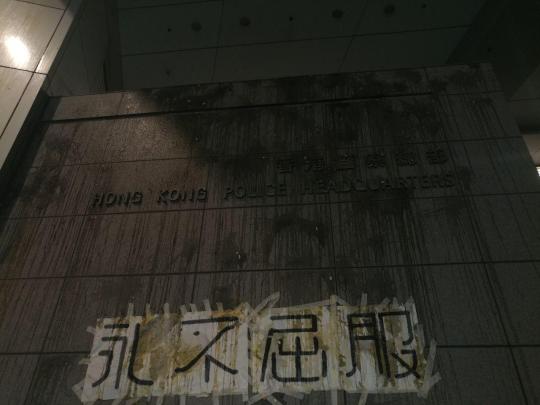

The front façade of the Hong Kong Police headquarters in Wan Chai, covered in egg yolks on the evening of June 21. Hundreds of protesters sealed the entrance, demanding the unconditional release of every person that has been arrested in relation to the struggle thus far. The banner below reads “Never Surrender.” Photo by KWBB from Tak Cheong Lane Collective.

“The left” is institutionalized and ineffectual in Hong Kong. Generally, the “scholarist” liberals and “citizenist” right-wingers have a chokehold over the narrative whenever protests break out, especially when mainland China is involved.

In the struggle against the extradition bill, has the escalation in tactics made it difficult for those factions to represent or manage “the movement”? Has the revolt exceeded or undermined their capacity to shape the discourse? Do the events of the past month herald similar developments in the future, or has this been a common subterranean theme in popular unrest in Hong Kong already?

We think it’s important for everyone to understand that—thus far—what has happened cannot be properly understood to be “a movement.” It’s far too inchoate for that. What I mean is that, unlike the so-called “Umbrella Movement,” which escaped the control of its founding architects (the intellectuals who announced “Occupy Central With Love And Peace” a year in advance) very early on while adhering for the most part to the pacifistic, citizenist principles that they outlined, there is no real guiding narrative uniting the events that have transpired so far, no foundational credo that authorizes—or sanctifies—certain forms of action while proscribing others in order to cultivate a spectacular, exemplary façade that can be photographed and broadcast to screens around the world.

The short answer to your question, then, is… yes, thus far, nobody is authorized to speak on behalf of the movement. Everybody is scrambling to come to terms with a nascent form of subjectivity that is taking shape before us, now that the formal figureheads of the tendencies you referenced have been crushed and largely marginalized. That includes the “scholarist” fraction of the students, now known as “Demosisto,” and the right-wing “nativists,” both of which were disqualified from participating in the legislative council after being voted in.

Throughout this interview, we will attempt to describe our own intuitions about what this embryonic form of subjectivity looks like and the conditions from which it originates. But these are only tentative. Whatever is going on, we can say that it emerges from within a field from which the visible, recognized protagonists of previous sequences, including political parties, student bodies, and right-wing and populist groups, have all been vanquished or discredited. It is a field populated with shadows, haunted by shades, echoes, and murmurs. As of now, center stage remains empty.

This means that the more prevalent “default” modes of understanding are invoked to fill the gaps. Often, it appears that we are set for an unfortunate reprisal of the sequence that played itself out in the Umbrella Movement:

appalling show of police force

public outrage manifests itself in huge marches and subsequent occupations, organized and understood as sanctimonious displays of civil virtue

these occupations ossify into tense, puritanical, and paranoid encampments obsessed with policing behavior to keep it in line with the prescribed script

the movement collapses, leading to five years of disenchantment among young people who do not have the means to understand their failure to achieve universal suffrage as anything less than abject defeat.

Of course, this is just a cursory description of the Umbrella Movement of five years ago—and even then, there was a considerable amount of “excess”: novel and emancipatory practices and encounters that the official narrative could not account for. These experiences should be retrieved and recovered, though this is not the time or place for that. What we face now is another exercise in mystification, in which the protocols that come into operation every time the social fabric enters a crisis may foreclose the possibilities that are opening up. It would be premature to suggest that this is about to happen, however.

In our cursory and often extremely unpleasant perusals of Western far-left social media, we have noticed that all too often, the intelligence falls victim to our penchant to run the rule over this or that struggle. So much of what passes for “commentary” tends to fall on either side of two poles—impassioned acclamation of the power of the proletarian intelligence or cynical denunciation of its populist recuperation. None of us can bear the suspense of having to suspend our judgment on something outside our ken, and we hasten to find someone who can formalize this unwieldy mass of information into a rubric that we can comprehend and digest, in order that we can express our support or apprehension.

We have no real answers for anybody who wants to know whether they should care about what’s going on in Hong Kong as opposed to, say, France, Algeria, Sudan. But we can plead with those who are interested in understanding what’s happening to take the time to develop an understanding of this city. Though we don’t entirely share their politics and have some quibbles with the facts presented therein, we endorse any coverage of events in Hong Kong that Ultra, Nao, and Chuang have offered over the years to the English-speaking world. Ultra’s piece on the Umbrella Movement is likely the best account of the events currently available.

Our banner in the marches, which is usually found at the front of our drum squad. It reads “There are no ‘good citizens’, only potential criminals.” This banner was made in response to propaganda circulated by pro-Beijing establishmentarian political groups in Hong Kong, assuring “good citizens” everywhere that extradition measures do not threaten those with a sound conscience who are quietly minding their own business. Photo by WWS from Tak Cheong Lane Collective.

If we understand “the left” as a political subject that situates questions of class struggle and labor at the center of its politics, it’s not entirely certain that such a thing even properly exists in Hong Kong. Of course, friends of ours run excellent blogs, and there are small grouplets and the like. Certainly, everybody talks about the wealth gap, rampant poverty, the capitalist class, the fact that we are all “打工仔” (jobbers, working folk) struggling to survive. But, as almost anywhere else, the primary form of subjectivity and identification that everyone subscribes to is the idea of citizenship in a national community. It follows that this imagined belonging is founded on negation, exclusion, and demarcation from the Mainland. You can only imagine the torture of seeing the tiresome “I’m a Hong Konger, not Chinese!” t-shirts on the subway, or hearing “Hong Kongers add oil!” (essentially, “way to go!”) chanted ad nauseam for an entire afternoon during recent marches.

It should interest readers from abroad to know that the word “left” in Hong Kong has two connotations. Obviously, for the generation of our parents and their parents before them, “Left” means Communist. Which is why “Left” could refer to a businessman who is a Party member, or a pro-establishment politician who is notoriously pro-China. For younger people, the word “Left” is a stigma (often conjugated with “plastic,” a word in Cantonese that sounds like “dickhead”) attached to a previous generation of activists who were involved in a prior sequence of social struggle—including struggles to prevent the demolition of Queen’s Ferry Pier in Central, against the construction of the high-speed Railway going through the northeast of Hong Kong into China, and against the destruction of vast tracts of farmland in the North East territories, all of which ended in demoralizing defeat. These movements were often led by articulate spokespeople—artists or NGO representatives who forged tactical alliances with progressives in the pan-democratic movement. The defeat of these movements, attributed to their apprehensions about endorsing direct action and their pleas for patience and for negotiations with authority, is now blamed on that generation of activists. All the rage and frustration of the young people who came of age in that period, heeding the direction of these figureheads who commanded them to disperse as they witnessed yet another defeat, yet another exhibition of orchestrated passivity, has progressively taken a rightward turn. Even secondary and university student bodies that have traditionally been staunchly center-left and progressive have become explicitly nationalist.

One crucial tenet among this generation, emerging from a welter of disappointments and failures, is a focus on direct action, and a consequent refusal of “small group discussions,” “consensus,” and the like. This was a theme that first appeared in the umbrella movement—most prominently in the Mong Kok encampment, where the possibilities were richest, but where the right was also, unfortunately, able to establish a firm foothold. The distrust of the previous generation remains prevalent. For example, on the afternoon of June 12, in the midst of the street fights between police and protesters, several members of a longstanding social-democratic party tasked themselves with relaying information via microphone to those on the front lines, telling them where to withdraw to if they needed to escape, what holes in the fronts to fill, and similar information. Because of this distrust of parties, politicians, professional activists and their agendas, many ignored these instructions and instead relied on word of mouth information or information circulating in online messaging groups.

It’s no exaggeration to say that the founding myth of this city is that refugees and dissidents fled communist persecution to build an oasis of wealth and freedom, a fortress of civil liberties safeguarded by the rule of law. In view of that, on a mundane level, it could be said that many in Hong Kong already understand themselves as being in revolt, in the way they live and the freedoms they enjoy—and that they consider this identity, however vacuous and tenuous it may be, to be a property that has to be defended at all costs. It shouldn’t be necessary to say much here about the fact that much of the actual ecological “wealth” that constitutes this city—its most interesting (and often poorest) neighborhoods, a whole host of informal clubs, studios, and dwelling places situated in industrial buildings, farmland in the Northeast territories, historic walled villages and rural districts—are being pillaged and destroyed piece by piece by the state and private developers, to the resounding indifference of these indignant citoyens.

In any case, if liberals are successful in deploying their Cold War language about the need to defend civil liberties and human rights from the encroaching Red Tide, and right-wing populist calls to defend the integrity of our identity also gain traction, it is for these deep-rooted and rather banal historical reasons. Consider the timing of this struggle, how it exploded when images of police brutalizing and arresting young students went viral—like a perfect repetition of the prelude to the umbrella movement. This happened within a week of the annual candlelight vigil commemorating those killed in the Tiananmen Massacre on June 4, 1989, a date remembered in Hong Kong as the day tanks were called in to steamroll over students peacefully gathering in a plea for civil liberties. It is impossible to overstate the profundity of this wound, this trauma, in the formation of the popular psyche; this was driven home when thousands of mothers gathered in public, in an almost perfect mirroring of the Tiananmen mothers, to publicly grieve for the disappeared futures of their children, now eclipsed in the shadow of the communist monolith. It stupefies the mind to think that the police—not once now, but twice—broke the greatest of all taboos: opening fire on the young.

In light of this, it would be naïve to suggest that anything significant has happened yet to suggest that to escaping the “chokehold” that you describe “scholarist” liberals and “citizenist” right-wingers maintaining on the narrative here. Both of these factions are simply symptoms of an underlying condition, aspects of an ideology that has to be attacked and taken apart in practice. Perhaps we should approach what is happening right now as a sort of psychoanalysis in public, with the psychopathology of our city exposed in full view, and see the actions we engage in collectively as a chance to work through traumas, manias, and obsessive complexes together. While it is undoubtedly dismaying that the momentum and morale of this struggle is sustained, across the social spectrum, by a constant invocation of the “Hong Kong people,” who are incited to protect their home at all costs, and while this deeply troubling unanimity covers over many problems,1 we accept the turmoil and the calamity of our time, the need to intervene in circumstances that are never of our own choosing. However bleak things may appear, this struggle offers a chance for new encounters, for the elaboration of new grammars.

Graffiti seen in the road occupation in Admiralty near the government quarters, reading “Carry a can of paint with you, it’s a remedy for canine rabies.” Cops are popularly referred to as “dogs” here. Photo by WWS from Tak Cheong Lane Collective.

What has happened to the discourse of civility in the interlude between the umbrella movement and now? Did it contract, expand, decay, transform?

That’s an interesting question to ask. Perhaps the most significant thing that we can report about the current sequence that, astonishingly, when a small fringe of protesters attempted to break into the legislative council on June 9 following a day-long march, it was not universally criticized as an act of lunacy or, worse, the work of China or police provocateurs. Bear in mind that on June 9 and 12, the two attempts to break into the legislative council building thus far, the legislative assembly was not in session; people were effectively attempting to break into an empty building.

Now, much as we have our reservations about the effectiveness of doing such a thing in the first place,2 this is extraordinary, considering the fact that the last attempt to do so, which occurred in a protest against development in the North East territories shortly before the umbrella movement, took place while deliberations were in session and was broadly condemned or ignored.3 Some might suggest that the legacy of the Sunflower movement in Taiwan remains a big inspiration for many here; others might say that the looming threat of Chinese annexation is spurring the public to endorse desperate measures that they would otherwise chastise.

On the afternoon of June 12, when tens of thousands of people suddenly found themselves assaulted by riot police, scrambling to escape from barrages of plastic bullets and tear gas, nobody condemned the masked squads in the front fighting back against the advancing lines of police and putting out the tear gas canisters as they landed. A longstanding, seemingly insuperable gulf has always existed between the “peaceful” protesters (pejoratively referred to as “peaceful rational non-violent dickheads” by most of us on the other side) and the “bellicose” protesters who believe in direct action. Each side tends to view the other with contempt.

Protesters transporting materials to build barricades. The graffiti on the wall can be roughly (and liberally) translated as “Hong Kongers ain’t nuthin’ to fuck wit’.” Photo by WWS from Tak Cheong Lane Collective.

The online forum lihkg has functioned as a central place for young people to organize, exchange political banter, and circulate information relating to this struggle. For the first time, a whole host of threads on this site have been dedicated to healing this breach or at least cultivating respect for those who do nothing but show up for the marches every Sunday—if only because marches that number in the millions and bring parts of the city to a temporary standstill are a pretty big deal, however mind-numbingly boring they may be in actuality. The last time the marches were anywhere close to this huge, a Chief Executive stepped down and the amending of a law regarding freedom of speech was moved to the back burner. All manner of groups are attempting to invent a way to contribute to the struggle, the most notable of which is the congregation of Christians that have assembled in front of police lines at the legislative council, chanting the same hymn without reprieve for a week and a half. That hymn has become a refrain that will likely reverberate through struggles in the future, for better or worse.

Are there clear openings or lines of flight in this movement that would allow for interventions that undermine the power of the police, of the law, of the commodity, without producing a militant subject that can be identified and excised?

It is difficult to answer this question. Despite the fact that proletarians compose the vast majority of people waging this struggle—proletarians whose lives are stolen from them by soulless jobs, who are compelled to spend more and more of their wages paying rents that continue to skyrocket because of comprehensive gentrification projects undertaken by state officials and private developers (who are often one and the same)—you must remember that “free market capitalism” is taken by many to be a defining trait of the cultural identity of Hong Kong, distinguishing it from the “red” capitalism managed by the Communist Party. What currently exists in Hong Kong, for some people, is far from ideal; when one says “the rich,” it invokes images of tycoon monopolies—cartels and communist toadies who have formed a dark pact with the Party to feed on the blood of the poor.

So, just as people are ardent for a government and institutions that we can properly call “our own”—yes, including the police—they desire a capitalism that we can finally call “our own,” a capitalism free from corruption, political chicanery, and the like. It’s easy to chuckle at this, but like any community gathered around a founding myth of pioneers fleeing persecution and building a land of freedom and plenty from sacrifice and hard work… it’s easy to understand why this fixation exerts such a powerful hold on the imagination.

This is a city that fiercely defends the initiative of the entrepreneur, of private enterprise, and understands every sort of hustle as a way of making a living, a tactic in the tooth-and-nail struggle for survival. This grim sense of life as survival is omnipresent in our speech; when we speak of “working,” we use the term “搵食,” which literally means looking for our next meal. That explains why protesters have traditionally been very careful to avoid alienating the working masses by actions such as blockading a road used by busses transporting working stiffs back home.

While we understand that much of our lives are preoccupied with and consumed by work, nobody dares to propose the refusal of work, to oppose the indignity of being treated as producer-consumers under the dominion of the commodity. The police are chastised for being “running dogs” of an evil totalitarian empire, rather than being what they actually are: the foot soldiers of the regime of property.

What is novel in the current situation is that many people now accept that acts of solidarity with the struggle, however minute,4 can lead to arrest, and are prepared to tread this shifting line between legality and illegality. It is no exaggeration to say that we are witnessing the appearance of a generation that is prepared for imprisonment, something that was formerly restricted to “professional activists” at the forefront of social movements. At the same time, there is no existing discussion regarding what the force of law is, how it operates, or the legitimacy of the police and prisons as institutions. People simply feel they need to employ measures that transgress the law in order the preserve the sanctity of the Law, which has been violated and dishonored by the cowboys of communist corruption.

However, it is important to note that this is the first time that proposals for strikes in various sectors and general strikes have been put forward regarding an issue that is, on the surface of it, unrelated to labor.

Our friends in the “Housewives Against Extradition” section of the march on September 9. The picture shows a group of housewives and aunties, many of whom were on the streets for the first time. Photo by WWS from Tak Cheong Lane Collective.

How do barricades and occupations like the one from a few days ago reproduce themselves in the context of Hong Kong?

Barricades are simply customary now. Whenever people gather en masse and intend to occupy a certain territory to establish a front, barricades are built quickly and effectively. There is a creeping sense now that occupations are becoming routine and futile, physically taxing and ultimately inefficient. What’s interesting in this struggle is that people are really spending a lot of time thinking about what “works,” what requires the least expenditure of effort and achieves the maximum effect in paralyzing parts of the city or interrupting circulation, rather than what holds the greatest moral appeal to an imagined “public” watching everything from the safety of the living room—or even, conversely, what “feels” the most militant.

There have been many popular proposals for “non-cooperative” quotidian actions such as jamming up an entire subway train by coordinating groups of friends to pack the cars with people and luggage for a whole afternoon, or cancelling bank accounts and withdrawing savings from savings accounts in order to create inflation. Some have spread suggestions regarding how to dodge paying taxes for the rest of your life. These might not seem like much, but what’s interesting is the relentless circulation of suggestions from all manner of quarters, from people with varying kinds of expertise, about how people can act on their own initiative where they live or work and in their everyday lives, rather than imagining “the struggle” as something that is waged exclusively on the streets by masked, able-bodied youth.

Whatever criticisms anybody might have about what has happened thus far, this formidable exercise in collective intelligence is really incredibly impressive—an action can be proposed in a message group or on an anonymous message board thread, a few people organize to do it, and it’s done without any fuss or fanfare. Forms circulate and multiply as different groups try them out and modify them.

In the West, Leninists and Maoists have been screaming bloody murder about “CIA Psyop” or “Western backed color revolution.” Have hegemonic forces in Hong Kong invoked the “outside agitator” theme on the ground at a narrative level?

Actually, that is the official line of the Chief Executive, who has repeatedly said that she regards the events of the past week as riotous behavior incited by foreign interests that are interested in conducting a “color revolution” in the city. I’m not sure if she would repeat that line now that she has apologized publicly for “creating contradictions” and discord with her decisions, but all the same—it’s hilarious that tankies share the exact same opinion as our formal head of state.

It’s an open secret that various pro-democracy NGOs, parties, and thinktanks receive American funding. It’s not some kind of occult conspiracy theory that only tankies know about. But these tankies are suggesting that the platform that coordinates the marches—a broad alliance of political parties, NGOs, and the like—is also the ideological spearhead and architect of the “movement,” which is simply a colossal misunderstanding. That platform has been widely denounced, discredited, and mocked by the “direct action” tendencies that are forming all around us, and it is only recently that, as we said above, there are slightly begrudging threads on the Internet offering them indirect praise for being able to coordinate marches that actually achieve something. If only tankies would stop treating everybody like mindless neo-colonial sheep acting at the cryptic behest of Western imperialist intelligence.

That said, it would be dishonest if we failed to mention that, alongside threads on message boards discussing the niceties of direct action tactics abroad, there are also threads alerting everyone to the fact that voices in the White House have expressed their disapproval for the law. Some have even celebrated this. Also, there is a really wacky petition circulating on Facebook to get people to appeal to the White House for foreign intervention. I’m sure one would see these sorts of things in any struggle of this scale in any non-Western city. They aren’t smoking guns confirming imperialist manipulation; they are fringe phenomena that are not the driving force behind events thus far.

Have any slogans, neologisms, new slang, popular talking points, or funny phrases emerged that are unique to the situation?

Yes, lots, though we’re not sure how we would go about translating them. But the force that is generating these memes, that is inspiring all these Whatsapp and Telegram stickers and catchphrases, is actually the police force.

Between shooting people in the eye with plastic bullets, flailing their batons about, and indiscriminately firing tear gas canisters at peoples’ heads and groins, they also found the time to utter some truly classic pearls that have made their way on to t-shirts. One of these bons mots is the rather unfortunate and politically incorrect “liberal cunt.” In the heat of a skirmish between police and protesters, a policeman called someone at the frontlines by that epithet. All our swear words in Cantonese revolve around male and female genitalia, unfortunately; we have quite a few words for private parts. In Cantonese, this formulation doesn’t sound as sensible as it does in English. Said together in Cantonese, “liberal” and “cunt” sounds positively hilarious.

Does this upheaval bear any connections to the fishball riots or Hong Kong autonomy from a few years ago?

A: The “fishball riots” were a demonstrative lesson in many ways, especially for people like us, who found ourselves spectators situated at some remove from the people involved. It was a paroxysmic explosion of rage against the police, a completely unexpected aftershock from the collapse of the umbrella movement. An entire party, the erstwhile darlings of right-wing youth everywhere, “Hong Kong Indigenous,” owes its whole career to this riot. They made absolutely sure that everyone knew they were attending, showing up in uniform and waving their royal blue flags at the scene. They were voted into office, disqualified, and incarcerated—one of the central members is now seeking asylum in Germany, where his views on Hong Kong independence have apparently softened considerably in the course of hanging out with German Greens. That is fresh in the memory of folks who know that invisibility is now paramount.

What effect has Joshua Wong’s release had?

A: We are not sure how surprised readers from overseas will be to discover, after perhaps watching that awful documentary about Joshua Wong on Netflix, that his release has not inspired much fanfare at all. Demosisto are now effectively the “Left Plastic” among a new batch of secondary students.

Are populist factions functioning as a real force of recuperation?

A: All that we have written above illustrates how, while the struggle currently escapes the grasp of every established group, party, and organization, its content is populist by default. The struggle has attained a sprawling scale and drawn in a wide breadth of actors; right now, it is expanding by the minute. But there is little thought given to the fact that many of those who are most obviously and immediately affected by the law will be people whose work takes place across the border—working with and providing aid to workers in Shenzhen, for instance.

Nobody is entirely sure what the actual implications of the law are. Even accounts written by professional lawyers vary quite widely, and this gives press outlets that brand themselves as “voices of the people”5 ample space to frame the entire issue as simply a matter of Hong Kong’s constitutional autonomy being compromised, with an entire city in revolt against the imposition of an all-encompassing surveillance state.

Perusing message boards and conversing with people around the government complex, you would think that the introduction of this law means that expressions of dissent online or objectionable text messages to friends on the Mainland could lead to extradition. This is far from being the case, as far as the letter of the law goes. But the events of the last few years, during which booksellers in Hong Kong have been disappeared for selling publications banned on the Mainland and activists in Hong Kong have been detained and deprived of contact upon crossing the border, offer little cause to trust a party that is already notorious for cooking up charges and contravening the letter of the law whenever convenient. Who knows what it will do once official authorization is granted.

Paranoia invariably sets in whenever the subject of China comes up. On the evening of June 12, when the clouds of tear gas were beginning to clear up, the founder of a Telegram message group with 10,000+ active members was arrested by the police, who commanded him to unlock his phone. His testimony revealed that he was told that even if he refused, they would hack his phone anyway. Later, the news reported that he was using a Xiaomi phone at the time. This news went viral, with many commenting that his choice of phone was both bold and idiotic, since urban legend has it that Xiaomi phones not only have a “backdoor” that permits Xiaomi to access the information on every one of its phones and assume control of the information therein, but that Xiaomi—by virtue of having its servers in China—uploads all information stored on its cloud to the database of party overlords. It is futile to try to suggest that users who are anxious about such things can take measures to seal backdoors, or that background information leeching can be detected by simply checking the data usage on your phone. Xiaomi is effectively regarded as an expertly engineered Communist tracking device, and arguments about it are no longer technical, but ideological to the point of superstition.

This “post-truth” dimension of this struggle, compounded with all the psychopathological factors that we enumerated above, makes everything that is happening that much more perplexing, that much more overwhelming. For so long, fantasy has been the impetus for social struggle in this city—the fantasy of a national community, urbane, free-thinking, civilized and each sharing in the negative freedoms that the law provides, the fantasy of electoral democracy… Whenever these affirmative fantasies are put at risk, they are defended and enacted in public, en masse, and the sales for “I Am Hong Konger” [sic] go through the roof.

This is what gives the proceedings a distinctly conservative, reactionary flavor, despite how radical and decentralized the new forms of action are. All we can do as a collective is seek ways to subvert this fantasy, to expose and demonstrate its vacuity in form and content.

At this time, it feels surreal that everybody around us is so certain, so clear about what they need to do—oppose this law with every means that they have available to them—while the reasons for doing so remain hopelessly obscure. It could very well be the case that this suffocating opacity is our lot for the time being, in this phase premised upon more action, less talk, on the relentless need to keep abreast of and act on the flow of information that is constantly accelerating around us.

In so many ways, what we see happening around us is a fulfillment of what we have dreamt of for years. So many bemoan the “lack of political leadership,” which they see as a noxious habit developed over years of failed movements, but the truth is that those who are accustomed to being protagonists of struggles, including ourselves as a collective, have been overtaken by events. It is no longer a matter of a tiny scene of activists concocting a set of tactics and programs and attempting to market them to the public. “The public” is taking action all around us, exchanging techniques on forums, devising ways to evade surveillance, to avoid being arrested at all costs. It is now possible to learn more about fighting the police in one afternoon than we did in a few years.

In the midst of this breathless acceleration, is it possible to introduce another rhythm, in which we can engage in a collective contemplation of what has become of us, and what we are becoming as we rush headlong into the tumult?

As ever, we stand here, fighting alongside our neighbors, ardently looking for friends.

Hand-written statements by protesters, weathered after an afternoon of heavy rain. Photo by WWS from Tak Cheong Lane Collective.

In reflecting on the problems concealed by the apparent unanimity of the “Hong Kong people,” we might start by asking who that framework suggests that this city is for, who comprises this imaginary subject. We have seen Nepalese and Pakistani brothers and sisters on the streets, but they hesitate to make their presence known for fear of being accused of being thugs employed by the police. ↩

“The places of institutional power exert a magnetic attraction on revolutionaries. But when the insurgents manage to penetrate parliaments, presidential palaces, and other headquarters of institutions, as in Ukraine, in Libya or in Wisconsin, it’s only to discover empty places, that is, empty of power, and furnished without any taste. It’s not to prevent the “people” from “taking power” that they are so fiercely kept from invading such places, but to prevent them from realizing that power no longer resides in the institutions. There are only deserted temples there, decommissioned fortresses, nothing but stage sets—real traps for revolutionaries.” –The Invisible Committee, To Our Friends ↩

Incidentally, that attempt was a good deal more spontaneous and successful. The police had hardly imagined that crowds of people who had sat peacefully with their heads in their hands feeling helpless while the developments were authorized would suddenly start attempting to rush the council doors by force, breaking some of the windows. ↩

On the night of June 11, young customers in a McDonald’s in Admiralty were all searched and had their identity cards recorded. On June 12, a video went viral showing a young man transporting a box of bottled water to protesters who were being brutalized by a squad of policemen with batons. ↩

To give two rather different examples, this includes the populist, xenophobic, and vehemently anti-Communist Apple Daily, and the “Hong Kong Free Press,” an independent English online rag of the “angry liberal” stripe run by expatriates that has an affinity for young localist/nativist leaders. ↩

28 notes

·

View notes

Link

“Our country has changed,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in his decision in Shelby County v. Holder. Congress had reauthorized the Voting Rights Act in 2006 by a 98-0 Senate vote and a gaping 390-33 tally in the House, but in 2013 the Supreme Court’s conservative justices voted 5-4 to strike down its key pre-authorization provision.

The result has been predictable ― systematic disenfranchisement of voters across the South and beyond, undoubtedly contributing to the defeat of Democratic gubernatorial candidates in Florida and Georgia (the latter is still being contested), and perhaps even enabling Ted Cruz in Texas to keep his Senate seat.

Now that Democrats have reclaimed the House and key governor’s mansions, and flipped hundreds of state legislative seats, we have a chance to do something about it. It’s time for them to go all-in on the universal right to transparent and accessible voting.

Re-reading the Roberts decision the day after the 2018 midterms is brutal. He blithely assures America that the days of Jim Crow are over and that the “current conditions” in no way resemble those of 1965. He writes that “while any racial discrimination in voting is too much, Congress must ensure that the legislation it passes to remedy that problem speaks to current conditions.” Because of that perceived mismatch, he claimed, he and his four colleagues took the “gravest and most delicate duty” of the Supreme Court and struck down a law as unconstitutional. He said that racism was still bad, of course, but that Congress would have to come up with some new rubric to protect the franchise of voters of color.

Congress, or rather the Republicans who have maintained control of at least one chamber of Congress since 2013, has not developed a new rubric. Instead, Republican lawmakers and officials, especially those in the very states governed by the VRA, have touted the nonexistent threat of voter fraud in order to systematically re-disenfranchise voters of color through a variety of means.

Some of their techniques are almost laughable, such as the preposterous claim to have “forgotten” power cords for the few voting machines sent to a precinct in Gwinnett County, Georgia. Others are dangerous, such as when Georgia police allegedly started harassing Democrats working to get out the vote. Mostly, though, the tactics are simple. Pass voter ID laws. Question every black registration. Close polling locations. Make the remaining locations remote, inaccessible, understaffed and under-equipped. Pour resources into voting sites in conservative districts. Reap the electoral rewards. These tactics have, regrettably, worked to ensure Republicans can continue their white minority rule.

THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

In this Oct. 30 photo, rejected mail-in ballots sit in a box as members of the canvassing board verify signatures on ballots at the Miami-Dade County Elections Department in Florida.

I wish we had transformed our voting system in 2009 after President Barack Obama took office, but there are many would-be priorities that slipped away during that brief window of total Democratic control. Once the 2010 midterms sailed by with massive Republican victories, we were well on our way to the undermining of democracy through virulent gerrymandering and widespread suppression.

Now it’s time to turn the tables. Instead of seeking nefarious benefits, though, Democrats are in luck that the party does best when they do what’s right. The more people receive their justly due franchise, in general, the more Democrats are elected. But Democrats should push for voting rights everywhere, rather than targeting potential strongholds, because the very nature of our democratic system of government depends on it.

The new House majority should draft clearly written (i.e., short) legislation that mandates automatic registration for all eligible voters and simple but radical measures like universal vote-by-mail. Then, Democrats should attach it to everything that comes out of the House, no matter how mundane. Why not make use of all the bills that pass without debate, like renaming a Texas courthouse or a post office in Florida or Virginia? While they are at the newly dubbed “U.S. Navy Seaman Dakota Kyle Rigsby Post Office” in Palmyra, Virginia, let’s make sure people can use the facility to send in their ballot without needing to take off work.

Republicans will cry foul and raise the specter of fraud, but right now the left can rebroadcast scenes from Tuesday’s election of lines snaking around the block and ballots rejected or altered, and take up the mantle of the defenders of democracy itself. Heck, remote balloting even saves money on staffing polling places and buying expensive machines, so it’s yet another argument that the Democrats are the party of fiscal prudence.

BLOOMBERG VIA GETTY IMAGES

Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker is out, but not before he put in place a vote suppression regime that may have thrown the state to Donald Trump in 2016.

We’ve got to do the same thing in every state and county that we can. Wisconsin’s new governor-elect, Tony Evers, must turn from defeating Scott Walker to fighting his heavily gerrymandered legislature that remains deep red. Walker’s voter ID regime arguably threw the state to Donald Trump in 2016; that can’t happen again. Michigan’s new governor, Gretchen Whitmer, faces similar challenges, though there’s less evidence its ID law swung the state in 2016.

Even polar opposites Kansas and New York can come into play. In the former, vote-suppressor-in-chief Kris Kobach lost the governor’s race to Democratic rival Laura Kelly. We’re not going to see Kansas turn blue in the next presidential election, but she has to fight Kobach’s legacy because Kansas’ citizens deserve free and fair elections. On the bluer end of the spectrum, New York’s backward voting laws have contributed to preventing the state from being the progressive forerunner it should be. Precinct by precinct, let’s reclaim our democracy.

Can we get a new Voting Rights Act through the Senate and onto Trump’s desk? Would he sign it? Would the Supreme Court toss this one out as well? That’s a fight I’m eager to see the Democrats take on.

Force the GOP to own its position as a minority party supported only by vote suppression. Make transparency, accessibility and universality of the franchise the watchword of the new Democratic House majority. It’s politically smart. It’s also the right thing to do. It’s too rare that ethics and savvy come together when talking about politics, so seize the moment.

#democratic party#voting rights#voter suppression#congress#2018 elections#2018 midterms#2018 midterm elections#GOOD ARTICLE#huffingtonpost#skypalacearchitect

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Passerby here - in regards to Fate/Grand Order, the reason they don't explain stuff in detail is because they kind of already did? The Fuyuki prologue in the actual mobile game is a longer, more in-depth tutorial, while the anime is an hour-long film. They can't do EVERYTHING in the short time slot they have. Also, the "explanation on Servants" thing is something repeated in every adaption and spinoff and just gets very redundant after a while, so it getting cut is understandable.

Also, arguing that they HAVE to explain EVERYTHING for newbies within the short 1 hour time slot for the F/GO anime is nonsensical considering the setting of Fuyuki - everything and everyone in Fuyuki (such as the statue Medusa Lancer destroys) only has significance if you’re familiar with Fate/stay night proper, and explaining EVERYTHING would waste time, especially since the premise of “Chaldea has no idea what originally happened in Fuyuki” makes explanation impossible anyway. Basically, you’re treating the Fate/Grand Order anime like some sort of standalone story, when in reality it’s more like the Rogue One to Fate/stay night’s mainline Star Wars, or the Fantastic Beasts to Harry Potter. Even if it’s a spinoff, demanding that it explain everything all over again is pointless and would detract from the plot given the very limited timespan, especially when the premise IS so heavily based in past installments. I hope you understand my points here.

I perfectly understand your points, but please keep in mind that you are making the exact same points as your predecessor which I have already rebuffed politely by reiterating my points of debate. I thank you for trying to state this case in more detail again, but my counter points remain solid and admittedly mired in my initial reactions to the material. The strength of my initial negative reactions is what prompted me to write my post, and upon re-view of the film, my problems with its structure, choreography, and colour design remain.

If I may attempt to restate your points, trying hard not to make a strawman : 1. there’s more info on everything in the game, 2. there’s more explanation of everything in the rest of the Nasuverse media, 3. this is for fans who already know everything and trying to explain too much in a short one hour featurette would be wasteful, 4. this should absolutely not be viewed in a standalone manner.

1. there’s more info on everything in the gameI understand this. But the movie was, as I was approaching it, supposed to get me pumped to play the game had I not already done so. It did not.

2. there’s more explanation of everything in the rest of the Nasuverse mediaI understand this. But it doesn’t defend against bad story structure.

3. this is for fans who already know everything and trying to explain too much in a short one hour featurette would be wastefulI contend this. Allow me to voice my contention in two manners, one polite, and one rude.Politely: Fans who enjoy this are absolutely deserving of their enjoyment, and as a fan placation vehicle this movie is certainly fantastic. I do not want to rid anyone of their enjoyment of this featurette. People should hold on to their joy where they can find it. : ) However, I still believe that a shortened running length was not truly a bar to cut out all explanation. I’m not expecting someone to dump typemoon.wikia.com onscreen. I was simply stating that within the world that the movie itself created with a protagonist who knows nothing and a fresh new aspect of the Nasuverse being presented, that a tiiiny bit more explanation would have been completely natural to present within the storytelling framework of the brand new setting. To fully explain Servant structure and the history of Fuyuki is not necessary. To explain more about Chaldaea and how it interacts with these structures is highly desirable. That Fuyuki is a mystery to Chaldaea is absolutely fine and a good mystery to hook the audience. That Chaldaea remains a complete mystery to the audience, apart from clichés that the audience can place upon it through inference, is unforgivable.Rudely: yeah I get it they made a pretty movie out of your waifus look at your waifus in good animation happy new year nasufans here’s a tv special to sell more nasushit including 5000 yen dvds but it’s worth it because WOW YOUR WAIFU she’s moving and going UGUU this is such a CATHARTIC pandering MOMENT you can’t wait to heal her with YOUR MAGIC RITUAL YA KNOW WHAT IM SAYIN[* “your waifu“ in this case referring to the fandom at large, not you specifically, holdharmonysacred, as I do not wish to make assumptions about you.]

4. this should absolutely not be viewed in a standalone manner.You bring up a comparison of Fate/ Grand Order to Rogue One and Fantastic Beasts. Here is where I very much would like to make more comparisons, as I have seen those movies and their attendant series as well! However, first it is important to keep in mind that whether one chooses to view a film as a standalone vehicle or as a chapter of a larger narrative is up to the individual viewer. Yet, ask any good author or script editor and they will tell you that the internal story of a feature should hold itself as a standalone story with good arc structure. While it’s true that Grand Order had a proper arc structure (problem, mysterious anomaly; action, fight to stop anomaly; resolution, bad guy temporarily wins, time to steel ourselves to do this again), I feel that it failed to present a story that an outsider could care about.

Honestly, Rogue One also failed to impress me as a standalone vehicle. It was infinitely more pandering than Grand Order, although at least it didn’t leave too many questions unanswered. Largely, it had more running time to establish its world, which Grand Order did not have. What Rogue One had in common with Grand Order was a dearth of likeable protagonists. At least the motivations of Rogue One’s antagonists are clear though, unlike R.E.O. Lev’s.

Fantastic Beasts actually worked as a standalone film. Parts of it that connected directly to the Potter storyline [erhem, Grindelwald] were frankly its worst aspects. Yet apart from that, the movie clearly established through its action and a bit of exposition the stakes of its world. There are wizards and magical beasts and non-wizards, the wizards try to hide from the non-wizards, never the twin shall meet, and in America magical beasts are not allowed to run free in non-wizard areas. The audience doesn’t have to know about rulings of the wizengamot or the history of wizarding in America to appreciate these in-story rules. Magic is shown throughout the movie, and major magical plot points like the obscurial are explained, though not exactly perfectly. But a bully attempt is made. One can watch Fantastic Beasts without knowledge of the Potterverse and still follow its structure while appreciating its characters who are presented with definite emotional ties and stakes in the movie. It’s not an outstanding movie, but it does very well to establish the basics of its world.

On the other hand, I maintain that Fate/ Grand Order failed to firmly establish the very basic internal rules that its world runs by either through exposition or onscreen action, preferring to hint at them, and that its characters were flat, especially the main character who could have been replaced with a soggy cardboard cutout for all it would have mattered.

I understand that the main character of this movie is supposed to be an audience insert surrogate, and a standin for an in-game protagonist, but that’s honestly no excuse for having him be void of emotional reaction to anything in the world around him except Mash. Mash is hurt? Oh noes, she’s pretty and talked to me so I guess we’re dating and now I’m upset. I’ve been transported to some techno-magic base? Oh well. Everyone else here has died en masse? Oh well. Now I’m in the past and things are attacking me? Oh well. That girl just died? Oh well. The guy who was nice to me turns out to be evil and he has some weird plan to do with wiping out the entire human race? OH WELL. I’m not asking for him to scream or anything, but the most proactive action he took in the entire movie to move the plot forward was to hold Mash’s hand in her climactic battle, and even then he did so blandly, not even a “ganbatte” or a “You mean a lot to me so don’t give up.” Every other scene where he took an action, he had stumbled into that place or been pushed there by other characters or the plot at large. The guy fell asleep during the one scene that would have explained shit to him and therefore us. How are we supposed to like him as a protagonist?

In conclusion, I do indeed understand the points you laid out in your asks, but feel that I have previously responded to most of them. Of the new concerns you bring up, my previous complaints about Fate/ Grand Order still hold sway. And yet, I do not at all wish to say that people should feel bad for liking Fate/ Grand Order. My stance is that I did not enjoy it, and it failed the rubric by which I was watching it. You state that my rubric is flawed, and that is a fair enough criticism. Please continue to enjoy the Fate/ universe and the Grand Order game. I hope they all bring you lots of continued enjoyment in the coming year!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Trouble With Empathy

Does your organization assess job candidates empathy skills? If not, why not? If yes, does your organization conduct empathy training? How? Why?

When my daughter started remote kindergarten last month, the schedule sent to parents included more than reading, math, art and other traditional subjects. She’ll also have sessions devoted to “social and emotional learning.” Themes range from listening skills and reading nonverbal cues to how to spot and defuse bullying.

As millions of students start the school year at home, staring at glowing tablets, families worry that they will miss out on the intangible lessons in mutual understanding that come with spending hours a day with kids and adults outside their own household. We want children to grasp perspectives of people different from themselves. Yet in recent years, empathy — whether we can achieve it; whether it does the good we think — has become a vexed topic.