#ED conducts major raids in five states

Text

सुबह का बड़ा समाचार: उत्तराखंड सहित देश के पांच राज्यों में ईडी की बड़ी छापेमारी

-अब तक के सबसे बड़े ‘फर्जी रजिस्ट्री घोटाला’ मामले में की जा रही है छापेमारीनवीन समाचार, देहरादून, 30 अगस्त 2024 (ED conducts major raids in Dehradun in Land Scam)। उत्तराखंड में अब तक के सबसे बड़े ‘फर्जी रजिस्ट्री घोटाला’ मामले में ईडी यानी प्रवर्तन निदेशालय उत्तराखंड सहित देश के पांच राज्यों दिल्ली, उत्तर प्रदेश, असम, और पंजाब के लुधियाना में छापेमारी की कार्रवाई कर रही है। सूत्रों के अनुसार,…

#Action#Big news#ED#ED conducts major raids in Dehradun in Land Scam#ED conducts major raids in five states#ED Raid#Enforcement Directorate#Land Registry#Scam#Uttarakhand#Uttarakhand News

0 notes

Text

IN-DEPTH: Neon Godzilla Evangelion, The Horrors of Hideaki Anno

"Something broken or deficient comes more naturally to me. Sometimes that thing is the mind. Sometimes it is the body."

-Hideaki Anno, creator of Neon Genesis Evangelion

"Monsters are tragic beings; they are born too tall, too strong, too heavy, they are not evil by choice. That is their tragedy."

- Ishiro Honda, director of Godzilla

Image via Amazon Prime Video

Horror is born of trauma. The pop-culture monsters we fear and are fascinated by tend to reflect our very real anxieties. Frankenstein tells the story of scientific progress so explosive that it risks leaving humanity behind. It Follows creates a nightmare vision of looming intimacy and the potential for unknowable disease. Leatherface, hooting at the dinner table with his brothers in rural Texas, was the child of economic angst, the crimes of Ed Gein, and of President Nixon's threat of a "silent majority" forcing Americans to reconsider whether or not they really knew their neighbors.

And Godzilla? Well, Godzilla is a metaphor for a bomb. A bunch of bombs, actually. But more important than that, he represents loss — the loss of structure, of prosperity, of control. Godzilla is our own hubris returning to haunt us, the idea that in the end, we are helpless in the face of nature, disaster, and even our own mistakes. We, as a species, woke him up and now we have to deal with him, no matter how unprepared we are.

Hideaki Anno understands this.

In 1993, he began work on Neon Genesis Evangelion, a mecha series profound in not just its depiction of a science fiction world but in its treatment of depression and mental illness. It is a seminal work in the medium of anime, a "must-watch," and it would turn Anno into a legend, though his relationship to his magnum opus remains continuous and, at best, complicated. It is endlessly fascinating, often because Anno seems endlessly fascinated by it.

In 2017, he would win the Japanese Academy Film Prize for Director of the Year for Shin Godzilla, a film that also won Picture of the Year, scored five other awards, and landed 11 nominations in total. Shin Godzilla was the highest-grossing live-action Japanese film of 2016, scoring 8.25 billion yen and beating out big-name imports like Disney's Zootopia. In comparison, the previous Godzilla film, Final Wars, earned 1.26 billion. Shin Godzilla captured the public's attention in a way that most modern films in the franchise had not, returning the King of the Monsters to his terrifying (and culturally relevant roots).

So how did he do it? How did Anno, a titan of the anime industry famous for his extremely singular creations, take a monster that had practically become a ubiquitous mascot of Japanese pop culture and successfully reboot him for the masses? How did Godzilla and Neon Genesis Evangelion align in a way that now there are video games, attractions, and promotions that feature the two franchises cohabitating? The answer is a little more complex than, "Well, they're both pretty big, I guess."

To figure that out, we have to go back to two dates: 1954 and 1993. Though nearly 40 years apart, both find Japan on the tail end of disaster.

Part 1: 1954 and 1993

On August 6th and August 9th 1945, two atomic bombs were dropped on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively. These would kill hundreds of thousands of people, serving as tragic codas to the massive air raids already inflicted on the island nation. Six days after the bombing of Nagasaki, Japan would surrender to the Allied forces and World War II would officially end. But the fear would not.

Within a year, the South Pacific would become home to many United States-conducted nuclear tests, just a few thousand miles from Japan. And though centered around the Marshall Islands, the chance of an accident was fairly high. And on March 1, 1954, one such accident happened, with the Lucky Dragon #5 fishing boat getting caught in the fallout from a hydrogen bomb test. The crew would suffer from radiation-related illnesses, and radioman Kuboyama Aikichi would die due to an infection during treatment. For many around the world, it was a small vessel in the wrong place at the wrong time. For Japan, it was a reminder that even a decade after their decimation from countless bombs, atomic terror still loomed far too close to home.

Godzilla emerged from this climate. Films about giant monsters had become popular, with The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms and a 1952 re-release of King Kong smashing their way through the box office, and producer Tomoyuki Tanaka wanted to combine aspects of these with something that would comment on anti-nuclear themes. Handed to former soldier and Toho Studios company man Ishiro Honda for direction and tokusatsu wizard Eiji Tsubaraya for special effects, Godzilla took form and would be released a mere eight months after the Lucky Dragon incident.

Image via Amazon Prime Video

It was a success, coming in eighth in the box office for the year and it would lead to dozens of sequels that would see Godzilla go from atomic nightmare to lizard superhero (and then back and forth a few times). America, sensing profits, bought the rights, edited it heavily, inserted Rear Window star Raymond Burr as an American audience surrogate, and released it as Godzilla: King of the Monsters! It was also very profitable, and for the next 20 years, every Japanese Godzilla film got a dubbed American version following soon in its wake.

Years went by. Japan would recover from World War II and the following Allied Occupation and become an economic powerhouse. But in the late '80s, troubling signs began to emerge. An asset price bubble, based on the current economy's success and optimism about the future, was growing. And despite the Bank of Japan's desperate attempts to buy themselves some time, the bubble burst and the stock market plummeted. In 1991, a lengthy, devastating recession now known as the "Lost Decade" started. And the resulting ennui was not just economic but cultural.

The suicide rate rose sharply. Young people, formerly on the cusp of what seemed to be promising careers as "salarymen," found themselves listless and without direction. Disillusionment set in, both with the government and society itself, something still found in Japan today. And though people refusing to engage with the norms of modern culture and instead retreating from it is nothing new in any nation, the demographic that we now know as "Hikikomori" appeared. And among these youths desperate to find something better amid the rubble of a once-booming economy was animator Hideaki Anno.

A co-founder of the anime production company Gainax, Anno was no stranger to depression, having grappled with it his entire life. Dealing with his own mental illness and haunted by the failure of important past projects, Anno made a deal that would allow for increased creative control, and in 1993, began work on Neon Genesis Evangelion. Combining aspects of the popular mech genre with a plot and themes that explored the psyche of a world and characters on the brink of ruin, NGE would become extremely popular, despite a less than smooth production.

The series would concern Shinji Ikari, a fourteen-year-old boy who suffers from depression and anxiety in a broken and terrifying world. Forced to pilot an EVA unit by his mysterious and domineering father, Shinji's story and his relationships with others are equal parts tragic and desperate, and the series provides little solace for its players. Anno would become more interested in psychology as the production of the series went on, and the last handful of episodes reflect this heavily.

Image via Netflix

After the original ending inspired derision and rage from fans, Anno and Gainax would follow it up with two sequel projects (Death & Rebirth and The End of Evangelion), and NGE's place in the pantheon of "classic" anime was set. Paste Magazine recently named it the third-best anime series of all time. IGN has it placed at #8 and the British Film Insititute included End of Evangelion on their list of 50 key anime films. The exciting, thoughtful, and heart-breaking story of Shinji Ikari, Asuka, Minato, and the rest has gone down in history as one of the best stories ever told.

So what would combine the two and bring Godzilla's massive presence under the influence of Anno's masterful hand? As is a miserable trend here, that particular film would also be spawned from catastrophe.

Part 2: 2011

"There was no storm to sail out of: The earth was spasming beneath our feet, and we were pretty much vulnerable as long as we were touching it," said Carin Nakanishi in an interview with The Guardian. The spasm she was referring to? The 2011 Tohoku earthquake, the most powerful earthquake in the history of Japan. Its after-effects would include a tsunami and the meltdown of three reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. The death toll was in the tens of thousands. The property destruction seemed limitless. The environmental impact was shocking. Naoto Kan, the Japanese Prime Minister at the time, called it the worst crisis for Japan since World War II.

It took years to figure out the full extent of the damage. Four years after, in 2015, 229,000 people still remained displaced from their ruined homes. The radiation in the water was so severe that fisheries were forced to avoid it. The cultivation of local agriculture was driven to a halt, with farmland being abandoned for most of the decade. And though the direct effects of it varied depending on how far away you lived, one symptom remained consistent: The inability to trust those who'd been sworn in to help.

"No useful information was being offered by the government or the media," Nakanishi said. Many voiced a fear that the government had not done its decontamination job properly or would not continue to help them if they returned to their former homes near Fukushima. Some felt the people making decisions were far too distant to truly understand what was going on. Many thought that the government had underestimated the danger. In a survey taken after the Fukushima meltdown, "only 16 percent of respondents ... expressed trust in government institutions." In most of these stories, citizens stepped in to help, feeling as if they had no other choice. Eventually, his approval ratings dropped to only 10 percent and Naoto Kan stepped down from his role as Prime Minister.

And what of Godzilla and Anno at the time? Well, the former lay dormant, having been given a 10-year hiatus from the big screen by Toho after the release of 2004's Godzilla: Final Wars. And though he'd show up in a short sequence in Toho's 2007 film Always Zoku Sanchome no Yuhi, they kept good on their promise. But Godzilla fans did not have to worry about a drought of Godzilla news. American film production company Legendary Pictures was busy formulating their own take on him, having acquired the rights a year before.

Meanwhile, Anno's post Evangelion life consisted of ... a lot more Evangelion. Though he'd direct some live-action films, his most newsworthy project was a series of Rebuild of Evangelion titles, anime films built with different aims (and created with a different mindset) than the original series. Departing Gainax in 2007, these would be created under his newly founded studio, Studio Khara.

Image via Netflix

And while it's obvious from the contents of Evangelion that Anno is interested in giant monsters and giant beings in general (Evangelion is pretty chockful of them), this fascination would only become more open. In 2013, he'd curate a tokusatsu exhibit at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tokyo, one that showcased miniatures from Mothra to Ultraman to Godzilla himself. About the exhibit, Anno would write:

"As children we grew up watching tokusatsu and anime programs. We were immediately riveted to the sci-fi images and worlds they portrayed. They put us in awe, and made us feel such suspense and excitement. (...) I think our hearts were deeply moved by the grown-ups' earnest efforts working at the sets that dwelled deep behind the images. (...) The emotions and sensations from those cherished moments have lead us to become who we are today."

For the presentation, he'd also produce a short film called A Giant Warrior Descends on Tokyo, with the monster based on a creature from Hayao Miyazaki's — his old boss and an inspiration to Anno, along with the man that Anno would accompany on a trip to the Iwata prefecture to show support for communities wrecked by the Tohoku earthquake — Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind manga. It was directed by Shinji Higuchi, an old collaborator of Anno's at Gainax who had served as Special Effects Director for Shusuke Kaneko's stellar Gamera trilogy in the '90s.

And though Higuchi would shortly go on to direct two Attack on Titan live-action films, their partnership would continue. Because in 2015, Toho announced they would team up to co-direct Godzilla 2016.

Part 3: 2016

Hideaki Anno has often thought of the apocalypse.

In an interview with Yahoo! News in 2014, he'd tell the interviewer he "sincerely thought that the world would end in the 20th Century," and that his fear of a nuclear arms race and the Cold War had heavily influenced Evangelion. However, his creative process isn't just permeated by man-made threats. "Japan is a country where a lot of typhoons and earthquakes strike ... It's a country where merciless destruction happens naturally. It gives you a strong sense that God exists out there."

This focus on earthly intervention by a divine presence is definitely a theme in Evangelion, but it also applies to Godzilla, a borderline invincible behemoth that was created to remind man of its mistakes. It's this kind of provoking thoughtfulness (among other things) that might have alerted Toho Studios of Higuchi and Anno's potential proficiency in re-igniting the slumbering Godzilla franchise. "[W]e looked into Japanese creators who were the most knowledgeable and had the most passion for Godzilla ...Their drive to take on such new challenges was exactly what we all had been inspired by," Toho would say of the pair.

Image via Amazon Prime Video

It was a few years in the making, though. After the creation of Evangelion: 3.0 You Can (Not) Redo, Anno fell into depression, causing him to turn down Toho's 2013 offer of the Godzilla project. But thanks to the support of Toho and Higuchi, Anno decided to eventually take them up on it. However, he did not want to repeat how he felt past filmmakers had been "careless" with Godzilla, stating that Godzilla "exists in a world of science fiction, not only of dreams and hopes, but he's a caricature of reality, a satire, a mirror image." Higuchi was also passionate about the project, saying, "I give unending thanks to Fate for this opportunity; so next year, I'll give you the greatest, worst nightmare."

Rounding out the NGE reunion with Shin Godzilla would be Mahiro Maeda, a character designer who would provide the look of Godzilla, and Evangelion composer Shiro Sagisu. Sagisu's music often includes motifs from Evangelion and the work of Akira Ifukube — who scored many classic Godzilla films — and is a great match for the monster. It's powerful stuff.

youtube

Anno's main concern was rivaling the first Godzilla, a film that remains effective to this day. So, in order to "come close even a little," he "would have to do the same thing." Thus, after over 60 years of monster adventures, Shin Godzilla became Godzilla's first real Japanese reboot, following a long line of films that were either direct sequels or had ignored the sequels to become direct sequels to the original. It would carry many of the same beats — monster arrives, people struggle to figure out how to stop it, they eventually do. The end. But unlike many Godzilla films, in which bureaucratic operations took a backseat to the scientists that would eventually figure out how to stop (or help) the Big G, they were front and center here.

And the depiction was often less than kind.

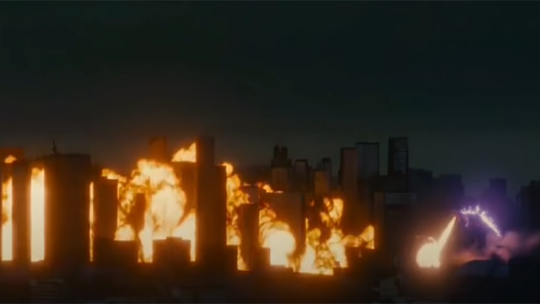

Instead of confident and sacrificial, the politicians found in Shin Godzilla are ludicrous in their archaic behavior, seemingly more concerned with what boardroom they're in than the unstoppable progress of the beast destroying their city. Most of their actions are played for comic relief, a tonal clash with the stark backdrop of the 400-foot-tall disaster walking just outside their offices. Multiple references are made to the Tohoku earthquake, the tsunami, and the Fukushima meltdown — including the waves that follow Godzilla as he comes ashore and the worry over the radiation Godzilla leaks into the land he travels across. One plot point even includes Japan grappling with the potential use of an atomic bomb on Godzilla from the United States, showing that over seventy years after the end of WWII, nuclear annihilation remains a terrifying prospect.

In the end, only a team organized by a young upstart that's mostly free from the processes of his slower, befuddled elders can save the day. That said, "save" isn't really the right word. Echoing Anno's statement that Japan is "a country where merciless destruction happens naturally," Godzilla is only frozen in place, standing still in the middle of the city, a monstrous question left to be solved. Whether it's Godzilla or a disaster like Godzilla, it is a problem that you must deal with, prepare for, and rebuild after. It will always be there.

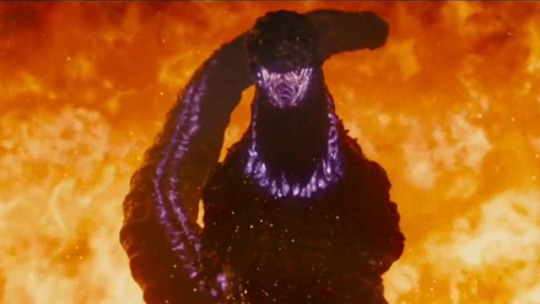

That said, the film isn't just a parody of quivering government employees out of their depth in the face of a cataclysm (distrust in the goodwill of authority figures is a theme also omnipresent in Evangelion). It's also a really, really rad monster movie. Godzilla is a scarred, seemingly wounded creature, his skin ruptured and his limbs distorted. He is not action-figure ready, even as he evolves into forms more befitting of total annihilation. As the Japanese military increasingly throws weaponry at him, he transforms to defend himself, emitting purple atomic beams from his mouth, his back, and finally his tail. Higuchi and Anno's direction is often awe-inspiring, whether the camera is tilted up to capture Godzilla from a street-level view, or panning around a building to face him head-on. Godzilla feels huge.

Image via Amazon Prime Video

Its this combination of ideas and execution that would cause Shin Godzilla to sweep the Japanese Academy Awards in 2017, and, excuse my pun, absolutely crush it at the box office. But an incredible movie wouldn't be the end of it. In fact, while Shin Godzilla was a successful Anno creation, it hadn't yet gone to battle with Anno's other most successful creation.

Not yet anyway.

Part 4: 2018

A few months before Shin Godzilla's release, Toho announced a "maximum collaboration" between Godzilla and Neon Genesis Evangelion, a team-up that first manifested itself in art and crossover merchandise. Art with the logo for NERV (the anti-Angel organization from Evangelion), with the fig leaf replaced by Godzilla's trademark spines showed up on a subsite for the Shin Godzilla film.

Meanwhile, video game developers Granzella and publisher Bandai Namco worked on City Shrouded In Shadow, a game where you played as a human trying to survive attacks from various giant beings, including some from the Godzilla universe and some from Evangelion. And though this wasn't specifically tied to Shin Godzilla — Godzilla looks much more like his design in the '90s series of movies, a monster style that was the go-to branding look for years after — it did make the idea of the two franchises co-existing in similar spaces a little less alien.

The big one came in 2018 when Universal Studios Japan declared that the following summer, it would be home to a meeting of the two titans in "Godzilla vs Evangelion: The Real 4-D." This ride/theater experience would give audiences a firsthand look at a clash between the EVA units and Godzilla. However, just as the horror of the original Godzilla had been diluted through various sequels that saw him becoming Japan's protective older brother, and just as the crushing melancholy of Evangelion feels a little less sad when you see Rei posing on the side of a pachinko machine, this ride would also be a reframing experience.

Godzilla is a threat, at first, as the Evangelion units zip around, blast him, and try to drop-kick him. But then, out of space, Godzilla's old three-headed foe King Ghidorah emerges. The golden space dragon provides a common enemy for the group and they work together to eliminate it. Godzilla, seemingly forgetting why he showed up to the ride in the first place, trudges back into the sea. He is now a hero, his spot as Earth's Public Enemy #1 seemingly neutered.

To this day, news of theme park attractions that bear the Shin Godzilla design consistently pop up, including one ride where you can zip line into Godzilla's steaming open mouth! But Toho doesn't seem open to a live-action sequel that many see as the obvious next step (though they would produce a trilogy of anime films that take place in a different monster timeline). Instead, they opted for beginning a kind of Godzilla shared universe, like the extremely popular Marvel Cinematic Universe. And Anno and Higuchi have moved on to their next revitalizing effort: a reboot of Ultraman.

Wes Craven, the director of A Nightmare on Elm Street once said, "You don't enter the theater and pay your money to be afraid. You enter the theater and pay your money to have the fears that are already in you when you go into a theater dealt with and put into a narrative ... Stories and narratives are one of the most powerful things in humanity. They're devices for dealing with the chaotic danger of existence." The creators at Toho certainly gave people that with Godzilla, just as Anno did with Neon Genesis Evangelion.

Image via Amazon Prime Video

But horror films are also entertainment, and soon these monsters are sequel-ized and commodified, losing their edge to the point that new minds are brought in to reboot them and help them move forward. It's a process we've repeated since people began telling stories to one another thousands and thousands of years ago. They help us confront the worst aspects of ourselves and of our worlds. It's what makes them vital. We need them. Like the next evolution of monsters sprouting from Godzilla's tail in the final frame of Shin Godzilla, the horror genre reaches out, grasping for fears that we have and fears that will one day come.

For more Crunchyroll Deep Dives, check out Licensing of the Monsters: How Pokemon Ignited An Anime Arms Race and The Life And Death Of Dragonball Evolution.

Daniel Dockery is a Senior Staff Writer for Crunchyroll. Follow him on Twitter!

Do you love writing? Do you love anime? If you have an idea for a features story, pitch it to Crunchyroll Features.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bank Raided, Arrests Made but RBI Still Restricts Withdrawals

The crisis has elevated at the cooperative bank recently placed under regulatory restrictions by India’s central bank. Multiple branches have been raided and several arrests were made. However, the RBI continues to impose a withdrawal limit, preventing bank customers from accessing their savings. The bank has 137 branches across India.

Also read: RBI Ban Stops Indian Police From Cashing Out Seized Crypto

Bank Raided, Executives Arrested

Since the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) placed regulatory restrictions on Mumbai-based Punjab and Maharashtra Cooperative Bank (PMC Bank) Ltd., more events have transpired. Major developments have led to an alleged Rs 4,355 crore (~$615 million) bank fraud, raids, and the arrest of executives. PMC Bank is a major cooperative bank in India with 137 branches across multiple states and over Rs 11,000 crore in deposits, local media detailed.

Four people have been arrested by the Mumbai police in connection with the case so far. The latest in police custody is former PMC Bank chairman Waryam Singh, who was picked up on Saturday. The other three arrests were former PMC Bank managing director Joy Thomas and promoters of Mumbai-based Housing Development and Infrastructure Ltd. (HDIL) group Rakesh Wadhawan and his son, Sarang Wadhawan.

According to information registered by the Mumbai police, HDIL group promoters colluded with the bank’s management to take out loans. When they were in default, bank officers allegedly used over 21,000 fictitious loan accounts to hide them, the police told the court Friday. The bank did not classify these loans as non-performing assets even when they were in default, hiding information from the RBI for over eight years.

Thomas reportedly wrote the central bank a confession letter detailing the scheme. He revealed that the bank’s exposure to HDIL group was around Rs 6,500 crore, which was over 73% of its total advances — all of which are in default.

The enforcement directorate (ED) raided six PMC Bank locations in and around Mumbai on Friday, local media reported. The ED said that the raids were conducted to gather evidence after a criminal complaint was filed under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act by the central agency. “Based on a complaint by an RBI-appointed administrator, the police complaint was filed earlier this week on charges of forgery, cheating and criminal conspiracy against the officials,” the Economic Times described. According to the initial investigation, the police said that the bank’s losses since 2008 amounted to Rs 4,355.46 crore.

People Demand Access to Their Money

The RBI announced that it had placed restrictions on PMC Bank on Sept. 24, including limiting how much customers could withdraw for a period of six months. Originally, the withdrawal limit was only 1,000 rupees (approximately $14). However, after many protests, the RBI raised the limit to 10,000 rupees. Then, on Oct. 3, it increased the withdrawal limit for depositors of PMC Bank to 25,000 rupees of the total balance of their accounts, while other restrictions remain unchanged.

“The Reserve Bank of India again reviewed the bank’s liquidity position and, with a view to reducing the hardship of the depositors, has decided to further enhance the limit for withdrawal to ₹ 25000 (rupees twenty five thousand only),” the RBI explained.

On Twitter, many users have been pleading with the RBI to allow them to withdraw the full amount of their hard-earned money. They also want the central bank to explain what will become of their deposits at the bank. One user wrote, “We need our entire money back … It’s our hard-earned money so … our right to it.” Another expressed, “RBI, you already know that increasing the limit is not helping anyone. This is pure hogwash.” Some claimed that they have had to shut down their businesses due to this limitation. Noting that people are literally begging the RBI to return their money, one user concluded:

It’s totally ridiculous that people are begging to get their own hard-earned money from [the] bank. It can happen to any bank.

Responding specifically to the new 25,000 rupee limit, one user exclaimed: “That’s not enough. We have all [our] savings in PMC Bank … Please release all our money.” Another user added, “Stop this nonsense of limit on our hard-earned money and let us take our all savings … without any limitations.”

PMC Bank customers trying to withdraw their money.

Meanwhile, the central bank has issued a statement in an effort to calm the public: “RBI would like to assure the general public that [the] Indian banking system is safe and stable and there is no need to panic.”

RBI’s Powers Challenged in Supreme Court

The RBI has also placed banking restrictions on all regulated entities, prohibiting them from providing services to crypto businesses including exchanges. The ban went into effect in July last year and banks subsequently closed accounts of crypto exchanges, forcing some of them out of business.

The banking ban has also affected the Pune city police department when it tried to transfer INR converted from the sale of the cryptocurrencies seized from an alleged kingpin of a Ponzi scheme. Rs 8.42 crore (~$1.2 million) is reportedly sitting in a bank account belonging to the company that operated a local crypto exchange which closed down its trading operations due to the banking ban. According to the Times of India, the police has filed a plea with a session court to move the money into its account.

Following the RBI ban order, a number of industry stakeholders filed writ petitions with India’s supreme court to challenge the ban. The court started hearing the case in detail in August, but the case is still ongoing.

What do you think of the situation at PMC Bank? What do you think of the RBI restricting people from accessing their savings? Let us know in the comments section below.

Images courtesy of Shutterstock, DNA India, and The Hindu.

Did you know you can buy and sell BCH privately using our noncustodial, peer-to-peer Local Bitcoin Cash trading platform? The Local.Bitcoin.com marketplace has thousands of participants from all around the world trading BCH right now. And if you need a bitcoin wallet to securely store your coins, you can download one from us here.

The post Bank Raided, Arrests Made but RBI Still Restricts Withdrawals appeared first on Bitcoin News.

READ MORE http://bit.ly/35d06v6

#cryptocurrency#cryptocurrency news#bitcoin#cryptocurrency market#crypto#blockchain#best cryptocurren

0 notes

Text

Bank Raided, Arrests Made – RBI Still Restricts Withdrawals

New Post has been published on https://coinmakers.tech/news/bank-raided-arrests-made-rbi-still-restricts-withdrawals

Bank Raided, Arrests Made – RBI Still Restricts Withdrawals

Bank Raided, Arrests Made – RBI Still Restricts Withdrawals

The crisis has elevated at the cooperative bank recently placed under regulatory restrictions by India’s central bank. Multiple branches have been raided and several arrests were made. However, the RBI continues to impose a withdrawal limit, preventing bank customers from accessing their savings. The bank has 137 branches across India.

Bank Raided, Executives Arrested

Since the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) placed regulatory restrictions on Mumbai-based Punjab and Maharashtra Cooperative Bank (PMC Bank) Ltd., more events have transpired. Major developments have led to an alleged Rs 4,355 crore (~$615 million) bank fraud, raids, and the arrest of executives. PMC Bank is a major cooperative bank in India with 137 branches across multiple states and over Rs 11,000 crore in deposits, local media detailed.

Four people have been arrested by the Mumbai police in connection with the case so far. The latest in police custody is former PMC Bank chairman Waryam Singh, who was picked up on Saturday. The other three arrests were former PMC Bank managing director Joy Thomas and promoters of Mumbai-based Housing Development and Infrastructure Ltd. (HDIL) group Rakesh Wadhawan and his son, Sarang Wadhawan.

According to information registered by the Mumbai police, HDIL group promoters colluded with the bank’s management to take out loans. When they were in default, bank officers allegedly used over 21,000 fictitious loan accounts to hide them, the police told the court Friday. The bank did not classify these loans as non-performing assets even when they were in default, hiding information from the RBI for over eight years.

Thomas reportedly wrote the central bank a confession letter detailing the scheme. He revealed that the bank’s exposure to HDIL group was around Rs 6,500 crore, which was over 73% of its total advances — all of which are in default.

The enforcement directorate (ED) raided six PMC Bank locations in and around Mumbai on Friday, local media reported. The ED said that the raids were conducted to gather evidence after a criminal complaint was filed under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act by the central agency. “Based on a complaint by an RBI-appointed administrator, the police complaint was filed earlier this week on charges of forgery, cheating and criminal conspiracy against the officials,” the Economic Times described. According to the initial investigation, the police said that the bank’s losses since 2008 amounted to Rs 4,355.46 crore.

People Demand Access to Their Money

The RBI announced that it had placed restrictions on PMC Bank on Sept. 24, including limiting how much customers could withdraw for a period of six months. Originally, the withdrawal limit was only 1,000 rupees (approximately $14). However, after many protests, the RBI raised the limit to 10,000 rupees. Then, on Oct. 3, it increased the withdrawal limit for depositors of PMC Bank to 25,000 rupees of the total balance of their accounts, while other restrictions remain unchanged.

“The Reserve Bank of India again reviewed the bank’s liquidity position and, with a view to reducing the hardship of the depositors, has decided to further enhance the limit for withdrawal to ₹ 25000 (rupees twenty five thousand only),” the RBI explained.

On Twitter, many users have been pleading with the RBI to allow them to withdraw the full amount of their hard-earned money. They also want the central bank to explain what will become of their deposits at the bank. One user wrote, “We need our entire money back … It’s our hard-earned money so … our right to it.” Another expressed, “RBI, you already know that increasing the limit is not helping anyone. This is pure hogwash.” Some claimed that they have had to shut down their businesses due to this limitation. Noting that people are literally begging the RBI to return their money, one user concluded:

It’s totally ridiculous that people are begging to get their own hard-earned money from [the] bank. It can happen to any bank.

Responding specifically to the new 25,000 rupee limit, one user exclaimed: “That’s not enough. We have all [our] savings in PMC Bank … Please release all our money.” Another user added, “Stop this nonsense of limit on our hard-earned money and let us take our all savings … without any limitations.”

PMC Bank customers trying to withdraw their money.

Meanwhile, the central bank has issued a statement in an effort to calm the public: “RBI would like to assure the general public that [the] Indian banking system is safe and stable and there is no need to panic.”

RBI’s Powers Challenged in Supreme Court

The RBI has also placed banking restrictions on all regulated entities, prohibiting them from providing services to crypto businesses including exchanges. The ban went into effect in July last year and banks subsequently closed accounts of crypto exchanges, forcing some of them out of business.

The banking ban has also affected the Pune city police department when it tried to transfer INR converted from the sale of the cryptocurrencies seized from an alleged kingpin of a Ponzi scheme. Rs 8.42 crore (~$1.2 million) is reportedly sitting in a bank account belonging to the company that operated a local crypto exchange which closed down its trading operations due to the banking ban. According to the Times of India, the police has filed a plea with a session court to move the money into its account.

Following the RBI ban order, a number of industry stakeholders filed writ petitions with India’s supreme court to challenge the ban. The court started hearing the case in detail in August, but the case is still ongoing.

Source: news.bitcoin

0 notes

Link

THE UNITED STATES TODAY may seem oblivious to the relentless global military activity carried out in its name, but, as Ken Burns’s recent documentary on the Vietnam War reminds us, that wasn’t always the case. Half a century ago, you would have had a hard time finding Americans unaware of our foreign wars and a very easy time finding people who objected to them — vociferously. Fifty years further back, President Woodrow Wilson’s call for the first large-scale dispatch of American troops abroad also provoked serious opposition — and preoccupied the lives of four of the five principals of Jeremy McCarter’s new book, Young Radicals. At the time, as McCarter points out, the United States had only the 17th largest army in the world, whereas now, a century of foreign interventions later, the American military budget is larger than that of the next eight or 10 runner-up nations combined.

McCarter starts his story on January 1, 1912, Walter Lippmann’s first day as executive secretary to George Lunn, the newly elected Socialist Party mayor of Schenectady, New York. The 22-year-old Lippmann has arrived with great expectations: he came recommended by Socialist Party founder and leader Morris Hillquit; the philosopher William James had once dropped by his dorm room to praise an article he wrote for a campus publication positing a brighter socialist-oriented future; in short, he was, according to McCarter, “the boy wonder of socialism.” Lippmann promptly produced a glowing account of the new Lunn administration for The Masses, the New York City socialist monthly started the previous year. But by the beginning of May (page seven of the book), he was out, now characterizing the Schenectady venture as “timid benevolence” and concluding that, while “[r]eform under the fire of radicalism is an educative thing[,] reform pretending to be radicalism is deadening.” By the next year, Lippmann, now “souring on socialism in all its forms,” had joined the staff of another new magazine, the New Republic, which its publisher called “radical without being socialistic.” It would rapidly become a leading voice for war preparedness, and Lippmann himself would soon take a job with the War Department (as the Defense Department was more appropriately called at the time), mobilizing for the war effort, his days as a radical effectively at an end — almost.

Lippmann knew John Reed at Harvard College when he was an officer in the Intercollegiate Socialist Society and Reed was a cheerleader and student actor. Their political trajectories subsequently crossed, with Reed first drawing public notice for his sympathetic, on-the-spot coverage of Pancho Villa’s Mexican revolutionary forces in 1913. Lippmann, who published his first book that same year, would have the more prominent career, being viewed as one of the nation’s most influential journalists for much of the next six decades. But it is Reed whose considerably shorter story seems to have retained the greater cachet as an embodiment of the zeitgeist: Warren Beatty played him in the 1981 Oscar-winning movie Reds.

Earlier in 1913, Reed had worked in support of 25,000 mostly immigrant silk industry laborers, who organized with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in a strike for better wages and working conditions in Paterson, New Jersey. When the New York press refused to report on the strike, hampering the union’s ability to take their story to a larger regional working class audience, someone came up with the idea of ferrying 1,000 laborers across the Hudson River to Madison Square Garden to tell the story themselves. Crossing the river in the other direction to check out the scene, Reed was arrested at the picket line and thrown in jail for four days; he subsequently assisted with the Madison Square Garden event. (Lippmann also helped, while grousing, McCarter tells us, about Reed’s “inordinate desire to be arrested.”) In addition to the speeches, the event featured an Italian folk song backed by a German chorus, IWW chants adapted to college football tunes, and the entire crowd of 15,000 rising to their feet for a finale of the “Internationale.” All in all, it was perhaps the greatest show the American labor movement ever produced.

Three years later, Reed joined a group of bohemian friends hoping to develop a new type of American theater in Provincetown, Massachusetts. Among their number was Eugene O’Neill, who would go on to become the only American playwright to win the Nobel Prize, but who at that point had never had a play actually performed. In 1917, Reed and wife Louise Bryant, a writer, activist, and feminist of some note, went off to cover the Russian Revolution, an experience Reed described in Ten Days That Shook the World (1919), one of the best and most influential firsthand accounts of a social revolution ever written. Reed and Bryant both, it should be added, were far from being “objective” observers or “disinterested” journalists. McCarter tells us that Reed had been obsessed with Russia ever since his mentor, renowned muckraker journalist Lincoln Steffens, “told him the new world was being born there.” In January 1918, Reed addressed the Third All-Russian Congress of Soviets, and not long after, Leon Trotsky appointed him the Soviet consul in New York. Even though the appointment didn’t work out, he came to be regarded as the “foremost American communist in the world,” sitting on the Executive Committee of the Communist International before resigning in frustration at the Russians’ heavy-handed role in the organization.

In late 1920, after Reed had died in Moscow of typhus five days short of his 33rd birthday, the American journalist and author Max Eastman delivered the eulogy at his funeral. The service was held in New York, but Reed’s body stayed in Moscow, one of three Americans whose remains are interred at the Kremlin wall. The editor-in-chief of The Masses, Eastman once referred to Reed as the publication’s “jail editor.” McCarter describes the New Republic as a “prematurely middle-aged magazine,” but no one ever said anything like that about The Masses. Based in Greenwich Village, the publication was, according to a manifesto co-authored by Eastman and Reed, “a revolutionary and not a reform magazine; a magazine with a sense of humor and no respect for the respectable.” But while The Masses may have been “conspicuously merry,” its politics were never frivolous. When The Masses accused the Associated Press of suppressing news about West Virginia mines and miners, Eastman was indicted for libel, along with cartoonist Art Young. Those charges were eventually dropped, but more would soon follow.

In many ways, this was a more genteel era than our own (Eastman once actually discussed the war with President Wilson), yet it is also true that, in some respects, the government’s repression of war opponents surpassed anything the 1960s antiwar movement encountered. The Masses would soon find itself running afoul of the newly passed Espionage Act, which allowed the Postmaster General to bar from the mail publications deemed to hamper the war effort. A ban was soon issued on all of the major socialist publications, starting with The Masses. Eastman, McCarter writes, “marvel[ed] that the American government has suppressed the socialist press more quickly and completely than the Germans did.” And that wasn’t the half of it: Socialist Party offices were raided by the authorities and vandalized by vigilantes, IWW members were arrested, peace marches were broken up. Socialist Party presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs, who had won six percent of the 1912 vote, had to conduct his 1920 campaign from the Atlanta Penitentiary, where his opposition to the war had landed him with a 10-year sentence under the Espionage Act.

With the Bernie Sanders campaign having brought the ideals of socialism some of their most positive public exposure in decades, Young Radicals suggests that a reconsideration may be in order as to the root cause of the “public relations” problems socialism has experienced during the past century. As McCarter shows, even before the Bolshevik Revolution and the birth and degeneration of Russian Communism (events generally considered decisive in souring many Americans on socialism), the jingoistic pro-war right was already pushing the idea that there was something “un-American” about the movement. After all, the American Socialist Party had actually stuck to the Socialist International’s antiwar principles and opposed the nation’s war effort, unlike the socialist parties in most of the other belligerent nations (the Russians being a notable exception).

Eastman himself subsequently moved hard left during the 1920s, embracing the Twenty-one Conditions for membership in the new Communist International that were rejected by many of the United States’s most prominent socialists, including Debs and Hillquit. Later he would tack to the right, regarding his prior positions as “half-fanatical glassy-mindedness” and dismissing socialism as “a dangerous fairy tale.” By 1955, he was serving on the editorial board of William F. Buckley Jr.’s conservative publication, National Review. His life was often held up as a caution to the 1960s New Leftists, purportedly illustrating the foolishness of their youthful radicalism.

Eastman, who lived to be 86, was in 1918 the only one of this book’s five central characters not to be affected by the worldwide influenza outbreak that killed more people than the war had itself. One of the epidemic’s casualties was Randolph Bourne, the first of the book’s characters to die, at age 32. Bourne’s personal life was dominated by his physical condition: a childhood illness had stunted his growth and twisted his spine, leaving him hunch-backed and short. A college classmate who heard him play the piano marveled at “how beautifully this strange misshapen gnome could make a piano sing and talk.” McCarter reports that, after publishing Bourne’s first essay and inviting him to a club lunch, the editor of The Atlantic cancelled “shortly after Bourne arrived, as he couldn’t bear to be seen with one so deformed.” (The reader’s inevitable curiosity as to his appearance is frustrated by the book’s lack of illustrations.)

The last years of Bourne’s political life were dominated by the war. After the New Republic declared that it was the intellectuals who had brought the nation into the conflict, and that this was to their credit, Bourne wrote that “[o]nly in a world where irony was dead could an intellectual class enter war at the head of such illiberal cohorts in the avowed cause of world liberalism.” Like a lot of Bourne’s writing, this essay would stand up equally well 50 years later as an indictment of the Kennedy Era’s “best and brightest” who did so much to bring us the disaster in Vietnam. American critic Lewis Mumford considered Bourne “perhaps the only writer who gauged” the “virulence of the animus” set loose by the world war “at its full worth.” As McCarter writes, “Bourne had predicted that leaders stupid enough to start a world war would be too stupid to end it.” It is not hard for contemporary readers to see that judgment as a critique of the state of affairs once called the global War on Terror but now known as everyday reality.

Alice Paul, the one female among McCarter’s five youthful radicals, was also the only one for whom the war always remained a secondary concern. Nothing would divert her attention from the suffrage issue until women actually had won the right to vote. Raised amid progressive ideas in a Quaker family and educated in them at Swarthmore, Paul found her life’s calling at age 22 when she saw crusading suffragette Christabel Pankhurst in action in Great Britain. Quickly enrolled in the movement led by Christabel’s mother Emmeline, Paul was arrested numerous times for disruption of public events. Suffragette strategy was to seek political prisoner status and then engage in hunger strikes; during her last prison stay, Paul was force-fed 55 times.

After this experience, which harmed her health permanently, Paul returned to the United States to recuperate and apply herself further to the cause. She made her mark nationally by helping to mount a march of 8,000 suffragists along Pennsylvania Avenue the day before Woodrow Wilson’s 1913 inauguration. After a congressional resolution was deemed necessary to secure the route, a half million people came to witness the colorful parade, whose way had to be cleared by the Pennsylvania and Massachusetts national guards, the local police having failed to do so. Paul herself soon met with Wilson, taking the new president aback by asking if he did “not understand that the Administration has no right to legislate for currency, tariff, and any other reform without first getting the consent of women to these reforms.”

Four years later, when Russian diplomats from the short-lived Kerensky government arrived at the White House for a meeting on the war effort, two suffragettes unfurled a banner declaring that “America is not a democracy” because “[t]wenty million American women are denied the right to vote.” After suffragists had stood outside the White House for over a year, Wilson endorsed legislation to expand the franchise, which passed the House in early 1918 and the Senate the following year, becoming the 19th Amendment to the Constitution when the requisite number of state legislatures endorsed it in 1920. Of all of McCarter’s subjects, Paul was unquestionably the most successful in achieving her goals, yet he believes that her “absolute single-mindedness” also led her to “evil” compromises with Southern white supremacists who feared that “enfranchising women will create more pressure to enfranchise black people.” In one editorial, Paul even claimed that the “enfranchising of all women will increase the relative power of the white race in a most remarkable way.”

Paul — and the National Woman’s Party she headed — continued the struggle by introducing the Equal Rights Amendment in 1923, which finally passed both houses of Congress in 1972 (though it stalled in the state legislatures). When Paul died in 1977 at the age of 92, she was the last of the book’s survivors. Eastman, whose rightward turn had led him to an editorial post at Reader’s Digest (according to McCarter, “the squarest and least radical magazine in America”) had died in 1969. Lippmann, 85 when he departed the planet in 1974, turned out to have one last spark of radicalism left in him. When most establishment liberals lined up behind the “domino theory” that brought us the Vietnam War, Lippmann refused to join in. Lyndon Johnson never forgave him, but Life magazine called him “the embodiment of meaningful opposition.”

With the rise of Donald Trump causing many Americans to scrutinize our politics and history more rigorously than they might otherwise have done, in an earnest search for alternatives to the status quo, McCarter has given us a well-written and compelling introduction to the lives of five young radicals who embarked upon a similar journey of resistance one century ago.

¤

Tom Gallagher is a writer and activist living in San Francisco. He is the author of Sub: My Years Underground in America’s School (2015) and The Primary Route: How the 99 Percent Takes on the Military Industrial Complex (2016).

The post Reform Under the Fire of Radicalism appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books http://ift.tt/2ysS3IW

0 notes