#Dr Chris Babcock

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

How to Care for Dental Implants

Dental implants are widely sought-after procedures dentists perform to restore damaged or extracted teeth. It has a high success rate, allowing dental patients to regain their smile and confidence. Dental implants offer a natural feel and functionality for chewing and effectively remedy issues like tooth decay, injury, and gum disease. However, proper care is essential to capitalize on dental implants' benefits fully.

One crucial aspect of dental implant care is the choice of toothbrush. Opting for a soft-bristled toothbrush is paramount, as brushes with hard bristles can potentially damage the enamel of the teeth and harm the implants. Additionally, hard-bristled brushes risk scratching the implants, leading to irreversible damage. Therefore, selecting a soft-bristled toothbrush, such as one made from soft nylon, helps safeguard the integrity of dental implants.

Another vital component of implant care is daily flossing. Flossing is key in thoroughly removing food particles and plaque that tend to accumulate between teeth. While brushing is essential, it may not effectively eliminate the buildup around implants, making daily flossing crucial. Using unwaxed tape or floss designed for individuals with dental implants ensures optimal oral hygiene.

Furthermore, abstaining from smoking and moderating alcohol consumption are integral aspects of implant maintenance. Smoking should be avoided altogether, as it hampers the healing process of implants by inflaming and weakening the surrounding gums. Similarly, excessive alcohol consumption impedes healing by promoting plaque accumulation on implants due to its high sugar content. Thus, minimizing these habits supports the long-term success of dental implants.

0 notes

Text

SUMMARY

Alex Gardner (Dennis Quaid) is a psychic who has been using his talents solely for personal gain, which mainly consists of gambling and womanizing. When he was 19 years old, Alex had been the prime subject of a scientific research project documenting his psychic ability, but in the midst of the study, he disappeared. After running afoul of a local gangster/extortionist named Snead (Redmond Gleeson), Alex evades two of Snead’s thugs by allowing himself to be taken by two men: Finch (Peter Jason) and Babcock (Chris Mulkey), who identify themselves as being from an academic institution.

At the institution, Alex is reunited with his former mentor Dr. Paul Novotny (Max von Sydow) who is now involved in government-funded psychic research. Novotny, aided by fellow scientist Dr. Jane DeVries (Kate Capshaw), has developed a technique that allows psychics to voluntarily link with the minds of others by projecting themselves into the subconscious during REM sleep. Novotny equates the original idea for the dreamscape project to the practice of the Senoi natives of Malaysia, who believe the dream world is just as real as reality.

The project was intended for clinical use to diagnose and treat sleep disorders, particularly nightmares, but it has been hijacked by Bob Blair (Christopher Plummer), a powerful government agent. Novotny convinces Alex to join the program in order to investigate Blair’s intentions. Alex gains experience with the technique by helping a man who is worried about his wife’s infidelity and by treating a young boy named Buddy (Cory Yothers), who is plagued with nightmares so terrible that a previous psychic lost his sanity trying to help him. Buddy’s nightmare involves a large sinister “snake-man.”

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

A subplot involving Alex and Jane’s growing infatuation culminates with him sneaking into Jane’s dream to have sex with her. He does this without technological aid—something no one else has been able to achieve. With the help of novelist Charlie Prince (George Wendt), who has been covertly investigating the project for a new book, Alex learns that Blair intends to use the dream-linking technique for assassination.

Blair murders Prince and Novotny to silence them. The president of the United States (Eddie Albert) is admitted as a patient due to recurring nightmares. Blair assigns Tommy Ray Glatman (David Patrick Kelly), a psychopath who murdered his own father, to enter the president’s nightmare and assassinate him—people who die in their dreams also die in the real world. Blair considers the president’s nightmares about nuclear holocaust as a sign of political weakness, which he deems a liability in the upcoming negotiations for nuclear disarmament.

Alex projects himself into the president’s dream—a nightmare of a post nuclear war wasteland—to try and protect him. After a fight in which Tommy rips out a police officer’s heart, attempts to incite a mutant-mob against the president, and battles Alex in the form of the snake-man from Buddy’s dream. Alex assumes the appearance of Tommy’s murdered father (Eric Gold) in order to distract him, allowing the president to impale him with a spear. The president is grateful to Alex but reluctant to confront Blair, who wields considerable political power. To protect himself and Jane, Alex enters Blair’s dream and kills him before Blair can retaliate.

The film ends with Jane and Alex boarding a train to Louisville, Kentucky, intent on making their previous dream encounter a reality. They are surprised to meet the ticket collector from Jane’s dream.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

The Dream Master Roger Zelazny

According to Roger Zelazny, the film developed from an initial outline that he wrote in 1981, based in part upon his novella “He Who Shapes” and novel The Dream Master. He was not involved in the project after 20th Century Fox bought his outline. Because he did not write the film treatment or the script, his name does not appear in the credits; assertions that he removed his name from the credits are unfounded.

DEVELOPMENT

DREAMSCAPE’s title encapsulates both the film and the mental landscape that its independent filmmakers occupied for almost three years. Its creators hoped that the production would not only prove to be a success, but that it would also give them the clout to go on to bigger, even more ambitious projects. Featuring elaborate special effects by Peter Kuran’s Visual Concept Engineering Company and makeup effects by Craig Reardon, the film was launched as the first outing of newly-formed Zupnik-Curtis Productions.

Producer Bruce Cohn Curtis is one of the few men left in Hollywood who still has ties to its fabled beginnings, the nephew of the legendary Harry Cohn, one of the founders of Columbia Pictures. Looking the producer, from his immaculately clipped hair down to his tailored, sharply creased suits, a chill falls over any set that Curtis walks onto. With a military air of no-nonsense, Curtis keeps a close eye on his productions and is happy only if filming is on schedule.

“I’m tyrannical on a set,” Curtis says with a smile of relaxed authority. “That’s why I use the people I have as well as I do. Many of the people on DREAMSCAPE have worked with me before and have come back because I am a perfectionist and won’t settle for less. I have a standard of excellence in my films that I’ve always maintained, no matter what the cost, so that even though you might not like the stories I’ve done, the look of the film is always rich.”

Remembering that he had to prove himself publicly in an industry filled with people just waiting for the newest Cohn to fail, for his first effort Curtis made OTLEY, a sharp-edged spy spoof/drama with Tom Courtney as an ersatz spy who finds his make-believe assignment being taken very seriously by the other side. The film died at the box office, but drew good critical notices. The industry sat up and noticed; Harry Cohn’s nephew was off and running.

Curtis partnered with various producers for awhile, including Irwin Yablans on HELL NIGHT, but chafed at being the junior partner without clout. The matter came to a head when he was making THE SEDUCTION with Yablans and grew tired of having his ideas ignored.

Curtis resolved to start his own company and make pictures his way. He found financial backing from businessman Stanley Zupnik, and was looking for scripts to start Zupnik-Curtis Productions when associate producer Chuck Russell brought in director Joe Ruben and the DREAMSCAPE script. Curtis had worked previously with both and gave the green light for Ruben and Russell to begin revising the script, written by David Loughery.

Ruben discovered Lowery’s script in 1981 at the William Morris Agency, which represents both artists. Lowery, a television writer, had come out to Hollywood in 1979 after winning a script writing contest sponsored by Columbia Pictures, while a student at the University of Iowa. Ruben had just finished directing the TV-pilot for BREAKING AWAY, and was looking for a new project.

Once Ruben started reading the DREAMSCAPE script he found he couldn’t put it down. The vision Loughery described was breathtaking, with rivers ablaze and boats filled with the undead. Ruben was excited by the property and showed it to Russell, his assistant director on JOY RIDE and GORP (also starring Dennis Quaid), films made with Bruce Cohn Curtis for producer Samuel Z. Arkoff. Russell suggested they take the script to Curtis and his new company.

It took seven months for Ruben and Russell to rewrite DREAMSCAPE; with Curtis providing detailed criticism and ideas throughout. Loughery was brought back in to help write the final draft.

“We knew some things in Loughery’s script, like the holocaust dream at the end, were so expansive that it was virtually un-filmable,” said Russell about the changes that were made. “The original ending was set in New York. We changed that so we could do the movie out here in Los Angeles. In Loughery’s script you saw all of New York on fire after the bomb had hit. You saw the Statue of Liberty, ferry boats filled with the undead, and flames across the harbor. It was really great, but I knew we couldn’t afford to do it like that.”

Putting a screenplay into production inevitably means rewrites and not always by the original writer. In the final billing, Loughery receives story credit, while sharing screenwriting credit with director Joe Ruben and associate producer Chuck Russell. When I started writing with Joe and Chuck,” he says, “the original screenplay was pretty ferme, about 108 pages. They wanted to work some more on the characters, and their relationships. That was a good thing the development of the characters gave the audience more reason to care for the people and what happened to them.”

One of the things that really worried us about the character of Alex Gardner is that he’s something of a smart ass. So, we were afraid the audience wouldn’t like him. As soon as Dennis went to work, it was obvious we weren’t going to have any problem.

“My favorite character is Tommy Ray, the psychotic psychic, played by David Patrick Kelly. He doesn’t have many scenes, but when he’s on, he does a great job. The ‘have a heart scene is going to be seen by the audience as a rip off of Temple of Doom, but the fact is we shot it months before Temple of Doom even went into production. That is Chuck’s idea; he has a grisly and macabre sense of humor.”

Russell and Ruben beefed-up the character of Buddy (Cory “Bumper” Yothers), the little boy whose nightmares are cured by the film’s dream research project. In Loughery’s script Buddy wasn’t a running character. The idea for Buddy’s character arose from concepts the writers picked up from the study of dream research.

“We found the case of a little boy who was having such terrible nightmares that he couldn’t sleep,” said Russell. “It was affecting him physically; we used that case as our model for Buddy. The first time in the film when Alex (Dennis Quaid) acts unselfishly is when he enters Buddy’s dream to try and help him. He rises to the occasion and fulfills the role of hero.”

THE DREAM CHAMBER

On an adjacent stage the set for the Dream Chamber was built. Outside, the set looked like a plywood igloo circled with florescent lights. Inside however, a small, padded chamber led to a main control room by a door and a large window. The set was a quiet haven, even when the normal racket of production was going on outside.

“The initial sketches of the set design for the Dream Chamber were some wild approaches that we felt were interesting, but not what we wanted,” Russell said. “Some of them made us feel too much like we were on a spaceship, while others were more like a classic, BRAINSTORM-type, wire-strewn lab. We decided we didn’t want a lot of whirling lights and buzzers, but something quiet and womb-like. It was a very difficult set to design because we were trying to make something that looked authentic, but we didn’t have any precedent for it.”

From an aesthetic standpoint, the design worked wonderfully. From a practical standpoint however, problems cropped up immediately that led to several delays in shooting. The set itself had been designed by Alan Jones without consulting with director of photography Brian Tufano. Jones then abruptly left the production for personal reasons so that when the set was built, Tufano had still not been consulted during the shuffle to find a new set designer. Tufano had great difficulty in setting up his lights and camera within the small confines of the set. An outside computer graphics firm had been brought in to supply authentic looking medical displays for the many small monitors built into the set. Unfortunately, the computer wouldn’t work right and left a full crew standing around collecting pay while technicians tried to figure out what had gone wrong with their expensive battery of equipment. Later, one of the technicians would quietly tell Russell that an Apple home computer would have been sufficient to give them the displays they wanted.

BEHIND THE SCENES / SPECIAL EFFECTS

“Some of the rough figures from effects companies were just staggering in the amount of money, research and development time they would need.” – Chuck Russell

Chuck Russell was told to shop around for people who could create the film’s extensive special effects and draw up a budget.

“It was very exciting to shop the script around and find out what could and couldn’t be done,” said Russell. “Some of the rough figures I got from effects companies were staggering in the amount of money, research and development time they would need. We just didn’t have the preparation time or budget of something like ALTERED STATES.

“When we found Peter Kuran’s VCE and Craig Reardon, and they got excited about the project, we knew they were perfect for it. They even helped sell the project because of their reputations, Reardon’s for working on Steven Spielberg’s POLTERGEIST and Kuran from his work with George Lucas.”

Russell assigned the live action makeup effects to Reardon, and the miniature and optical work to Kuran’s VCE company. Richard Taylor’s MAGI company was also asked to contribute computer animated imagery for the film’s “Dream Tunnel” effects. For the Dream Tunnel, Russell and Ruben wanted a semi-abstract look different from the other effects work in the picture, a “hazy.” dreamlike look, with an object or two from the upcoming scene to form and float towards the viewer to act as a visual cue for what was about to happen.

The effects sequences were storyboarded by Len Morganti; the budget was finalized on the basis of those storyboards. Because director Joe Ruben had not worked with special effects before, he carefully went through each scene with the storyboard artist.

“I knew that I had to be totally committed to my boards,” said Ruben. “I spent a lot of time thinking through the sequences and how I wanted to shoot them because I knew if I didn’t, the film would go out of control because the special effects people wouldn’t know what they were responsible for and what had to be done with each shot. I was able to get just what I was looking for. Morganti would sketch out something and if I asked him to move it a little lower and more to the right, he’d be able to do it with just a few strokes of his pencil. It was almost like working with a camera.”

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

BUDDY”S NIGHTMARE

To try and save money while providing a sense of heightened realism, Russell and Ruben had wanted to shoot the “Buddy” dream, the little boy’s nightmare, on location.

“We found an old Victorian house and were actually shooting,” said Russell. “We realized that by the time you put in the lightning and thunder, it was going to look like Vincent Price was going to come around the corner. It was too on the nose, too traditional. We asked Jeff Stags, our art director, to do something different. He came up at the last minute with the idea of a forced perspective set, sort of Dr. Caligari style. It was a small set, but much more effective, as well as inexpensive. Buddy’s dream is really my favorite because it has much more impact, even though it’s not as spectacular as the last dream.”

Another problem that cropped up involved Reardon’s Snake man suit. Although an impressive work up close, Ruben felt that at even minor distances, it would seem as just a man in a rubber suit. Ruben and Russell still hoped that flickering low-level lighting would help. but Ruben began to realize that even with the extensive work he had put into planning the storyboard angles, the lighting was not going to be enough to sell the suit to an audience. Reardon firmly disagreed, “Contrary to negative thinking about rubber suits, you’ve got to see them as something delightful, and full of potential for doing something wonderful,” said Reardon. “You have to think of them almost as toys. Right when we were about to shoot the basement struggle scene, I went aside with Ruben and said there are two ways of looking at this; you can think of this as a rubber suit which will look bad, or as something which, with the proper angles and lighting, will convince people that they’re looking at a living, breathing, snarling Snake man. Now when Ruben first saw it, he said ‘Oh boy, Reardon, I don’t know…it’s a rubber suit. I thought that had a dangerous ring to it if he really believed it, which was hard to tell because he, Russell, and Loughery had this camaraderie among the three of them based on this constant derogatory kidding. That’s well and good and worth a few chuckles, but where it begins to become pernicious is when it begins to condition thinking to be truly negative.”

Reardon also objected to the low-level lighting strategy that Ruben and cinematographer Brian Tufano used to film the suit. “Tufano seemed to have a fine contempt for any kind of supplementary light which would be, in logical terms arbitrary, but in dramatic terms exciting and interesting … something that would catch the eye, something that would fill in a face or create a little cross light to show textures,” said Reardon. “The naturalistic photography Tufano used can be very detrimental, I think, to SF and fantasy stories. You contrast this with the work of John Hora, who shot THE HOWLING and GREMLINS, and you see that special effects profit enormously from using special tiny spots and direct lighting. But I didn’t feel it was my place to raise the issue.”

Reardon did try to get his viewpoint across to the filmmakers by preparing a lighting test on video. The test was crude but illustrated the alternative Reardon was suggesting. “They ignored it,” said Reardon of the test. “Yet, when they got on the set, they were completely vapor locked on the suit. They didn’t know what to do with it, and they didn’t have any ideas. All the storyboards that had been prepared in advance were completely ignored. Not once did I see anybody bring up a storyboard and crack it open and say that for this frame here we need to set up this angle. All the audacious plans evaporated. Ruben was at a loss to shoot special effects or rubber suits.”

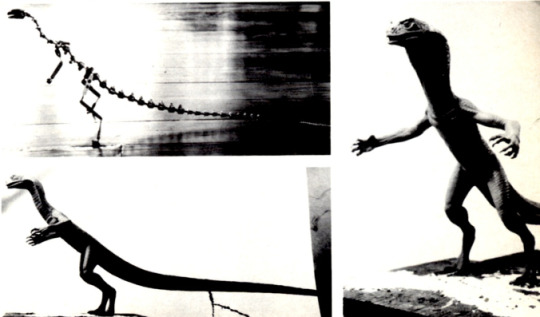

Aupperle s first job was to coordinate the sculpture of the stop-motion Snake man, which was being done by Steve Czerkas, with the suit being built by Craig Reardon.

“They told me that they wanted to feature Craig’s suit prominently, so I was going to try and make the miniature as close as possible to Craig’s suit,” said Aupperle. “We started with a man’s armature and sculpted Craig’s design over it. I knew we were going to have to make some changes, like making the tail longer so it could whip around, but I wanted to avoid one of those instances where the suit never matches the miniature. I’d run back and forth to Craig and measure his design with calipers just to make sure we were dead on.

“Since Craig’s suit was being done in pieces our model was the first time the producers saw the way the design was going to come together. They wanted more changes than I ever expected. They actually had Steve Czerkas re-sculpt the model. It got away from the manlike design and no longer really matched the suit. I was a little concerned that the two would intercut, but that’s what they insisted upon.”

Causing Aupperle the most concern was the production’s seeming lack of respect for the story boards. *They wanted to be able to use Craig’s suit any way they wanted,” said Aupperle. “They didn’t want to be tied down by storyboards. At one time they asked me to revise the storyboards. They said they’d just have to wing it on the set. That attitude left me little to do until they were done with the live action. I found the situation very distressing.”

Perhaps the greatest disappointment for Reardon was the scant use made of a full snake-man costume. The suit appears in the film for just a few frames, as the man-snake breaks through a door; most of the action originally planned for Cedar was replaced by Jim Aupperle’s animation using models built, following Reardon’s design, by Steve Czerkas.

THE SNAKE MAN

Most changes made in the script did not alter Loughery’s story significantly. In Loughery’s original draft, the creature that menaces Buddy in the boy’s dream and later reappears as the creature stalking the President and Alex was to be a rat-man. “We changed that because so much had been done with werewolves,” said Russell. “This was right after THE HOWLING and AMERICAN WEREWOLF IN LONDON and we felt the difference between a man with a rat’s face and a man with a wolf’s face would be minimal.

“We wanted to take a different approach,” Russell continued. “Not the direction of John Carpenter’s Thing but something identifiable, so that when Tommy Ray changed into something to scare Alex, you would be able to see that it was Tommy Ray’s version of the same creature. Joe Ruben wanted to go with something that scared him, and since he’s scared of snakes, we went in that direction. I did some sketches of a snake creature and came up with something that really excited us because it was a departure from anything either of us had seen before. I think part of it came to me from my memories of seeing THE SEVEN FACES OF DR. LAO. When we showed it later to our effects people, Peter Kuran and Craig Reardon, they were really sparked by it too.

A stop-motion animator was the last member of the effects team to be hired, done through VCE. Both Russell and Ruben had agreed early on that the best and cheapest way to get what they wanted from the Snake man sequences would be with a mixture of live-action and stop-motion effects, but they were unsure just how they would mix the combination.

“I knew we would need a good animator,” said Russell. “I knew a live-action Snake man with its long neck and swishing tail would never work in a master shot. We didn’t have umpteen million dollars for physical effects.” Russell and Ruben planned to use low-key, flickering lighting for the sequences in order to seamlessly blend the two effects techniques.

Said Russell, “ Joe and I sat down with the special effects people on the Buddy sequence storyboards, which is the first appearance of the Snake man, and asked which way it made more sense to do it? It made sense to do the wide shots in stop motion and the close-ups in live action, and in the cases where we weren’t sure, we would have both of them overlap and whichever worked better, then that’s what we would go with.”

Although this arrangement was made in good faith and with the best intentions, the decision to let the two techniques overlap and not make a clear distinction between which shots would be assigned to each ultimately proved to be a decision that led to tensions and feelings of betrayal between makeup expert Craig Reardon and the production company.

Opticals were also used to create the clouds and background sky for the first dream that Quaid enters, the vertigo dream where he goes into the mind of a steelworker and falls. “There’s one shot where Dennis Quaid is supposed to be falling. said Kuran. “I spent some time trying to figure out how a person should fall so it will look right on film. We had a good plate of a falling background, and they rigged an elaborate harness at Raleigh to hold Dennis. When we were on the set. Ruben asked me how a person should fall, and I went through the motions of what Dennis should do, but Joe didn’t do that. He told Dennis to do something else that looks really corny. He ruined the shot. There was no way that I could think of to fix it and I think it looks really cheesy right now.

THE PRESIDENTS NIGHTMARES

At a budget of over $300,000 for some 90-odd cuts, DREAMSCAPE was one of the largest jobs VCE had taken on, as well as one of the most difficult. As the producers were continually asking VCE to create more or make changes with what they had done, Kuran wasn’t under pressure to have all the special effects done by the original deadline. Kuran pretty much improvises his effects as he goes along. The more they wanted him to do, the less certain he was about how much longer it would actually take to finish the effects. One thing was certain. There was no way they’d be able to get the movie out in the fall as Russell had originally hoped.

In a way though, the delays had been a good thing; something everyone was almost afraid to acknowledge because of all the tribulations the film had gone through. Kuran was creating the effects layer by layer, and even with only early tests to show, the effects still looked very good. It helped convince Curtis that even though the schedule and budget had gone to hell, it was still within limits he could work with—he was getting a better product for his money than he ever dreamed possible. The more Kuran tinkered with the visuals, the better they got. The live action footage of the actors had come out better than expected, too. Quaid and Von Sydow were marvelous in their roles, and if they could just get the effects to come out anywhere near what had been described in the script, they all began to feel they might have a movie yet, even if they did have to grimace a bit when they realized that the work on the film was still far from over.

Working with Zupnik-Curtis productions was not without its problems for Kuran in the beginning. Because Curtis had never worked with special effects before, he wasn’t sure what to expect.

“We started getting pressure from them early on,” said Kuran. “They had a rough cut of some of the sequences for us to work from, and they wanted to see something. But they kept changing the cutting without realizing that it meant we’d have to go back and redo the whole scene. There was a trolley shot that they wanted to make longer by one foot of film. At that point, all the backgrounds had been shot to length. All the miniatures had been broken down. I managed to talk them out of that one.”

Another problem is the very nature of post-production work. “When somebody does a movie, they make a little mistake here and a little mistake there, and if it doesn’t work, they just kind of throw the shit over their shoulders and it lands on them in post-production,” said Kuran. “Unfortunately, this is where we do most of our work. People are at their worst to deal with in post-production. They’re under deadlines, and if the movie doesn’t work they’re in even worse shit. The people who shot the movie are gone and they usually refuse to accept the fact that the movie is crummy because of them. Lots of people can go onto a production and create a lot of shit and come off smelling like a rose because the movie’s not finished when they leave it.”

Although VCE was contributing some 90 cuts to the film, the majority of the effects were going to be clustered around the holocaust dream near the end, and at the start, including the terrific A-Bomb teaser which opens the film. “I thought the bombs in THE DAY AFTER just didn’t look right,” said Kuran. “They looked so dark and cold. You look at a nuclear test and you can see it’s a very bright fireball, so we wanted a very hot look to our bomb.”

The Trolly/Subway Cart

Reardon’s and Kuran’s most elaborate work is seen in the climactic sequence, a surreal view of the day after Nuclear Armageddon. Dennis Quaid enters a dream which represents the President’s worst fears of nuclear war, the setting is an old trolley car that travels among the bombed-out ruins of Washington, D.C., past several surrealistic tableaux-travelling mattes and miniatures courtesy of Peter Kuran’s V.C.E. David Kelley, Plummer’s henchman, enters the dream as well, for a climactic confrontation with Quaid.

For the holocaust dream at the end, Kuran’s basic effects strategy was to have a live-action foreground element, an intermediate miniature behind that, and then have a matte or tinted water tank shot as the background. The scenes were difficult because Kuran needed something that would convey a sense of extremely large scale while still having realistic detail, a tall order on the show’s tight budget.

Russell had originally wanted to do the holocaust effects scenes first and rear-project them as they were shooting the live action. Kuran pointed out that it would take thousands and thousands of feet of film to try and generate the footage they would need, and that they would have a better chance of making sure the background footage matched with the live-action trolley car if they shot the trolley first and then had it to play the backgrounds against.

“Jim Belohovek and Sue Turner built the miniatures for the scenes, and we photographed them in different layers,” said Kuran. “To get good depth of field, we shot them at one frame per second. Then we started adding the fires. Because those had to be slowed down, we shot them at 72 frames a second. We don’t have any motion control equipment. I set up a dolly for the camera, filled the room with smoke, then lit the fires. It takes a couple of seconds to get the camera up to speed. Then we pushed the dolly down the tracks until eventually timed the push right and got it to look the same speed that we thought the trolley would be moving at. The background is a water tank shot that we used to make it look moody by adding some glows and fires. Counting everything I’d say there’s about 20 elements in that shot.”

While Kuran labored in the bowels of VCE, director Ruben and Academy Award winning editor Richard Halsey were slowly cutting the film together using unfinished optical tests that were the right length and Jim Aupperle’s Snake man animation. Kuran had been able to find them an east coast underground filmmaker named Dennis Pies (pronounced “pees”) to do the Dream Tunnel effects and the stuff looked wonderful. It was exactly what they wanted. But now it was time to decide how they were going to mix the live action Snake man and the animation, and to a great degree, they were coming down against the live action footage.

With the will to manipulate the dream to his own ends, Kelly at one point extends his fingernails into stilletos, which he uses to rip the heart from the car’s conductor, with the logic of dreams, the trolley then becomes a subway car, populated with a dozen grisly war victims, looking more dead than alive, Shortly after, Kelley transforms into a snake monster.

Reardon details the other effects he did for Dreamscape. “Tommy Ray Kelly transforms with knives springing from his fingers. He uses these to tear out someone’s heart which sits beating in his fingers,” the effects Technician says. “We made a prosthetic hand and an artificial heart for this scene.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

“We made 12 mutants up for them, Reardon says of the subway denizens, “all extremely exaggerated in their ugliness, so that, in the heavy shadows and flickering light that was planned for the shot, they would still prove effective. The design is heavy-handed, but suitably macabre for the scene.

“I hogged all the major sculpture on the picture for myself, but there were a number of other people working with me on this that also deserve mention. My greatest praise must go to Bruce Kasson, who took the weight off my shoulders where mechanical work is concerned. He worked out the mechanical effect used for the death of one of the characters at the end, as well as the stilleto fingernails. David Miller was our acrylic man, doing all the hard plastic pieces, and certainly one of my right hand men in doing the sculpture, along with David Cellitti.

Snake Man Transformation Effect

Following the completion of principal photography, there was a brief hiatus, during which Reardon re-stirred his somewhat-dampened enthusiasm, before tackling the transformation sequence.

Replacement animation is a variety of stop motion that uses separate, slightly differing sculptures, rather than the movable models most frequently associated with the form. Pioneered by George Pal, replacement animation is nowadays seen mostly in David Allen’s television commercials featuring such animated characters as Mrs. Butterworth and the Pillsbury Doughboy. Reardon’s suggestion to try this technique for an unusual transformation. Because of the frame-by-frame nature of the animation process, the sequence would be a short one-less than two seconds in sculpting work than Reardon (or, most likely, anyone else) had ever expended on a transformation effect of such short duration; 32 heads, each altered slightly from the previous head in sequence, each making a barely more than subliminal appearance in the film. It was this rapidity, and the violence of the change, that Reardon felt would make it entirely unique.

“The major problem was one of time,” Reardon says. “How was I to produce 32 different heads for this sequence within a reasonable schedule? The first thing you want to consider in a situation like this is, can you do it full-size? It took me about 15 seconds of heavy thought to realize that would be a killer, because of the molds that would be involved, and the sheer awkwardness of doing such an extensive sequence in full scale. From the beginning, they wanted David Kelley’s features discernible in the snake head’s face, so l also briefly considered taking a cast of Kelley’s face and using reduction techniques, like special shrinking molds, to bring it down to scale-but there is enough distortion in the reduction process that it wouldn’t likely be worth the effort. So I finally decided on doing a miniature portrait sculpture based on his features.

“One way to have gone would have been to produce molds of each and every stage cast one head, alter it a little further, make a mold from that and cast another stage. I ruled that out; it takes about a day to make one mold, so it would have taken a full month to prepare for the sequence.

“Instead, I took a master mold of the first stage turned out a dozen or so duplicates of that, and altered each of them to cover the first third of the total transformation. I then made another mold from the last of these, and changed those progressively. That way, I had to make no more than three molds. As the work progressed, I did some rough tests on video, which helped to show up a number of small glitches. Some of these proved very difficult to correct-seen side by side, two heads might appear to match perfectly, but tiny variances would show immediately on video.”

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

A chief problem with all stop motion effects is that of temporal aliasing,” a term used to describe the unnatural look of objects seen to be in motion, but not blurred as they would be if actually filmed in real-time. All along, Chuck kept saying, ‘I hope this won’t look like animation,” says Reardon, “and of course all I could say was, I hope so, too.’

“Jim Aupperle, who did the stop motion animation on the snake monster, and my friend Randy Cook, made some suggestions to counter that problem. Both suggested that if each stage would be slightly dissolved into the next stage, that would soften the edges, and disguise whatever anomalies there were from one head to the next. So Peter took the negative and a dupe negative, printing them to a single positive with overlapping frames, so that no single frame gives a really razor sharp image of one sculpture.

The Caves

Another kind of problem arose in shooting the climax of the President’s holocaust dream, set in a cave-like underground grotto decorated with fires, twisted girders and a glowing pool of green water. Originally it was planned to shoot the scene on a section of the ruins” set at Raleigh Studios. But Russell found out that he could get a few days shooting time at Bronson Canyon. The site, long a favorite locale for low-budget productions, is actually a short “Y” shaped tunnel through a jutting canyon wall in the nearby Hollywood hills. Open at all three ends and with a high ceiling, Ruben and Russell felt they could put up a more effective set inside the cave at relatively little cost to the production.

The art department scrambled on something like 48 hours notice to come up with a revised set for the cave. They did well, but lighting the set so that the lights themselves wouldn’t show was a difficult task made harder by the fact that creating the pool of water just past the junction of the “Y” in the cave had turned the rest of its sandy floor into gritty muck that forced the crew to support the lights and camera on wooden planks and sandbags the best they could. Working in the enclosed confines quickly turned miserable too. Brian Tufano, who had been hired because of his work on QUADROPHENIA and THE LORDS OF DISCIPLINE, is yet another British cinematographer who likes to use smoke to diffuse his lighting to give the set greater visual depth. Every time Ruben went for a take, Tufano’s assistants would pump the small, sealed cave full of hot, oily smoke and wait to see if the density was right. While the crew and stars quietly gasped behind their respirators, either more smoke would be pumped in if it wasn’t enough.

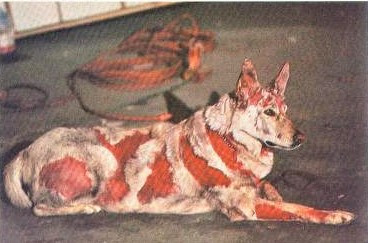

According to Craig Reardon, the first scenes that were supposed to be shot in the caves were thought to be relatively straightforward. Quaid, followed by Albert, is moving through the cave when they are attacked by a mutant dog. For the dog’s costume, Reardon’s assistant, Michiko Tagawa, had made some wonderfully revolting costumes.

“They were beautiful.” Reardon said. “They had entrails bulging out of the body and exposed rib cages and boils and french fried skin. Now we were told that a Doberman would wear the costume, and in fact, the trainer had auditioned the dogs in a costume they worked in on the BUCK ROGERS television show. So Michiko went to a great deal of trouble to measure the Dobermans and I contributed sculptures for the heads while she built the body parts up from reject castings for the subway zombies.” Once we got them suited up at the Bronson location however, the Dobermans refused to perform.

“The dogs trouped around in the mud and the zippers and their fur got packed with it,” said Reardon. “It was a disaster. They took one of the suits and tried to put it on a German Shepherd, a dog which is considerably different in body build.”

In his big scene the dog was supposed to run a short distance and jump at Quaid. In take after take however, the dog merely trotted up to Quaid and stopped at his feet to try and shake the costume off. Eyes turned on the dog’s embarrassed handlers who quickly explained that the dog usually didn’t act like that; it was probably because he felt uncomfortable with the costume.

Reardon snipped parts of the costume’s legs away, hoping to make it more comfortable, but this produced no better reaction. Next, the dog’s owners took to furiously waving a little furry target at the dog. then quickly sticking it just inside Quaid’s shirt while everyone enthusiastically urged the dog to attack. This made the dog think everyone just wanted to play. It would run up to Quaid, half-hop once, then bark excitedly while waiting for his trainers to get the toy again.

Quipped Reardon, Bruce Cohn Curtis said the mutant dog looked like someone’s dirty laundry running across the floor.” Finally the dog made one decent leap past Quaid and Ruben called it a take. The shot is still in the film, although the rest of the mutant dogs were replaced with German Shepherd with their fur shaved in patches and dabbled with red goo.

“The script also called for these two raggedy dogs to chase after Quaid and Albert in the dream. It seemed that the easiest way to achieve a really striking appearance for the dogs would be to suit them in a costume covered with foam latex. I consulted with the trainers on the feasibility of it, and they said

‘Yeah, sure.’ So l sculpted two mutated dog heads, and Michiko Tagawa, a very good craftsperson who’s done work with Winston and Burman, did a beautiful job on the body suits-really hideous and nasty. She took some reject castings from the subway mutants, and reworked them into twisted body shapes, warped, burned and decked with growths. But the dogs wouldn’t wear them, and the trainers sort of shrugged, and said ‘What do you expect?’

“Those trainers were let go, and replaced by Karl Miller, who allowed them to shave his dogs in erratic patches, and we gobbed all kinds of blood, goo and crap on them. Good enough, but it’s unfortunate that Michiko’s suits will never be seen.”

VCE generated the bits and pieces that would help add life and highlights to the live action effects. A red glow was added to the mutant dog’s eyes, as well as crawling purple electrical effects when the dogs vanish. Opticals materialized David Patrick Kelly’s nunchaku weapons smoothly into his hands as well as allowed Dennis Quaid to heal his wounds and transform himself into Kelly’s father.

Snake Man Showdown

The next scene planned for the cave involved Quaid and Albert, discovering it is a dead end and that the Snakeman is right behind them. It comes out of a side tunnel, snarls, and attacks Quaid. Ruben decided he wanted to use the full-sized Snakeman suit for the shot, and Reardon was given short notice to get it ready. At the time, Reardon was working full tilt to prepare the suit needed for the basement struggle in the boy’s nightmare. A different head would be needed for the cave sequence.

“Russell got a hold of Bronson Canyon and said we’ve got to do the Kelly head to look like David Patrick Kelly, playing the President’s assassin) right away. You can’t change things around like that. I said I’d try when I should have told him no.”

Ruben shot Reardon’s live Snakeman suit in the cave, although eventually discarded most of it and replaced the scene with a stop-motion cut. Also discarded was a small but important effect Reardon had worked very hard on getting right, a brief shot where Dennis Quaid “heals” a wound in his shoulder.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

“We created a sort of bite effect, then put a plastic membrane over it and melted it with a plastic solvent so that when they ran the film backwards, the wound would heal,” explained Reardon. “It didn’t work as well as it did on the bench, which is frequently the case, but you did get a feeling of the actual fleshy material knitting itself. They opted to have Peter Kuran redo it with animation.”

More successful was a Reardon designed effect where Kelly, now distracted by an ingenious ploy of Quaid’s, reverts to a half-human, half-snake form. While diverted, Albert sneaks up behind him and drives a length of pipe through Kelly’s chest. For this shot, Reardon made a false chest with a mechanical rubber pole section inside that was connected to a spring and operated by cable. Albert would sneak up holding the pipe, then drop it out of camera sight as he lunged for Kelly, and the rubber pipe would burst through a section of painted tissue paper. Although the complex mechanical effect took some time to rig, it was accomplished in only three takes and is gruesomely realistic. It made for a happy interlude before the crew was to run into yet more problems once they left Bronson Canyon and returned to Raleigh Studios.

Dave Millers Unused Snake Man

“I also worked on a snake man head, the one that was originally going to be in the elevator sequence, emerging from the head of Dennis Quaid. But then, they had some kind of quibble over Craig’s head of Quaid–they said it didn’t look like him, or some such garbage-and they hired Greg Cannom to do that sequence over. Greg did another head of Quaid, which they wound up not even showing, though it looked perfect, and another snakeman, which-sorry, Greg I didn’t care for too much. It didn’t seem to have much definition; it was hard to tell what it was. Plus, it was pretty badly edited.” – David Miller

BOB BLAIR’S DREAM DEMISE

The “Buddy” dream completed the bulk of the main shooting. DREAMSCAPE moved from the largest soundstage at Raleigh into one small stage for what was hoped would be the final shot of the would grasp what was happening. Because Quaid’s strike against Plummer was to be a surprise, Ruben and Russell felt it was absolutely necessary to make sure that the lighting look realistic right up to the moment of the attack. This meant shooting the effect not with lighting that would highlight the makeup, but with ordinary florescent lighting. Reardon hated the lighting, but went along with Ruben’s insistence that changing the lighting would tip-off people that something was about to happen.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

About a month earlier, in late June, Reardon had supplied a transformation head, known as a “change-0” head in the business, for a scene late in the film in which Dennis Quaid confronts political schemer Christopher Plummer in the one place where Plummer is vulnerable, inside Plummer’s own dream. Quaid borrows a trick from dream assassin David Patrick Kelly and changes into his own version of the Snakeman before killing Plummer. The effect was planned to first show Quaid’s head beginning to change, cut back to Plummer as the Snakeman’s hands shoot out for his throat (a very brief scene which was shot earlier) then a quick cut back to Dennis Quaid’s Snakeman head coming for the camera.

“We prepared a head, which I felt was better than a lot of THE HOWLING heads,” said Reardon. “We didn’t content ourselves with just having the face bulge out. We had the eyes blink, and when they opened they were snake eyes. At the same time the neck elongated and the cheeks distended, and the eyes began to pop out of their sockets. The mouth opens unnaturally wide and the teeth elongate. But nobody liked it. Ruben said to me, ‘Geez Reardon, I expected something like AMERICAN WEREWOLF IN LONDON.’ That’s great. You give me six months and six hundred thousand dollars and maybe you could get that. Besides, that effect was five different heads. I told them all along that I was only going to come up with one head and do as much with it as I could.”

Neither Russell nor Ruben had been happy with the head when Reardon had brought it in. Under the flat lighting of the elevator mockup, the hair looked too bushy and still, the face too lifeless, and the neck far thicker than Quaid’s. The head didn’t work well either. with eyes that frequently jammed as they started to roll up. It took several takes to get the mechanism to work right. But beyond that, when Ruben and Russell saw footage of the effect, they realized that what they thought would be a good visual just wasn’t that exciting.

“Forget that it wasn’t convincing on film,” Ruben said. “When I saw it, I just realized that we needed a more shocking effect.”

“It wasn’t exciting enough,” added Russell. “We didn’t realize that until we saw it. It was a subtle effect that just wasn’t explosive enough. Craig’s head didn’t show anything either that would connect it with the Snakeman, and we decided we needed that, so we racked our brains and decided on something simple, like a guy’s head ripping apart with the Snakeman’s head coming out of the pieces.”

Russell contacted Reardon, but by this time, Reardon was both fed up with the production and busy trying to finish the replacement animation for David Patrick Kelly’s Snakeman transformation so he could be done with the film. Since Reardon was busy, Russell had to find someone who could do the effect and do it quickly. He decided on Greg Cannom, a former assistant to Rick Baker and Rob Bottin. Cannom’s first solo assignment was THE SWORD AND THE SORCERER, and more recently he assisted Baker with the apes for GREYSTOKE.

Cannom had talked with Russell about a year before DREAMSCAPE about another film project that never went through. Cannom was interested in the assignment, but checked with Craig Reardon first, before committing himself. Reardon gave his blessing. Cannom went into his workshop and tried an effect which would combine the two concepts that Russell discussed, creating a skull that would not only split apart, but split apart and turn into a monster at the same time. “I could see the use of the Snakeman with the kid’s nightmare, but going into an adult’s nightmare, I thought it should be a lot more horrendous and scary,” said Cannom.

Cannom’s first prototype makeup was deemed unacceptable by producer Bruce Cohn Curtis. It was a bitter decision because of the amount of effort Cannom had put into it. Cannom took a fiberglass skull which he cut and hinged so it could be pulled apart. Inside the skull, Cannom used a soft foam and sculpted a hideous face so that when the skull was pulled apart, the jaw would drop down and the foam face would come out to form the monster.

“I loved Cannom’s first approach,” said associate producer Chuck Russell. “I think it was terrific. The dangerous thing about the makeup was that in a very quick cut, with a man splitting his head open and something gooey, dark, and spongy coming out, it might look like brains. It was hard to argue for it because of that.”

Curtis told Cannom that they wanted something closer to Reardon’s Snakeman concept. Cannom tried to figure out how to fit Reardon’s Snakeman design into a reworked version of the splitting skull but finally gave up and settled for a two-piece approach. Cannom first built a small, embryonic Snakeman head which would be moved like a hand puppet inside the skull after it split apart. Cannom wanted to stop the camera and replace the small head with a fullsized but slimmer Snakeman head that would rise out of the neck and lunge for the camera dripping goo and skin. As with Reardon before him, Cannom was less than happy with the treatment he felt his makeup got from Ruben and Curtis. Assisted by Jill Rocklow, Kevin Yagher and Brian Wade, Cannom did the effect, but felt little enthusiasm for the final product.

“Bruce Cohn Curtis and the other producer, Jerry Tokofsky, were so insulting and rude to me it was incredible,” said Cannom. “It was like they already had something against me and wanted to find fault. I never want to see Bruce Cohn Curtis again.

“I don’t really think my effect works either,” added Cannom. “It’s not done the way we wanted to set it up. We were very careful about it. First, the skull would split apart, then we would cut away, put the snake creature back into the neck and put skin all around it, and then have it come at the camera. I spent hours getting the chicken skins for the makeup and preparing them, then setting-up the effect. Ruben looked at it and said, ‘That’s not what I want. No neck and no skin. I just want the head coming at the camera.’ I told him that didn’t make any sense! But that’s what he wanted, so we did it his way.”

POST PRODUCTION

Because Ruben and Halsey had been able to do much of the editing work while the final opticals were being generated, the final scoring and assembly of the footage was completed quickly. Curtis had a finished film only a month later and premiered it to his friends in mid-January at a small mixing theater in Hollywood. Although there were some clunky spots that hadn’t been fixed because of time and budgetary problems, the final cut was deftly edited around most of them and they were visible only if you knew what to look for. The audience gave the film a big hand and Curtis was very happy, as well as Kuran. Russell, Ruben and Loughery, who now looked forward to having a potential hit associated with their names. Although Craig Reardon liked the film, he was still unhappy with director Ruben.

Ruben defended his decision to replace Reardon’s work. “Craig was under tremendous pressure to deliver an awful lot of complicated physical effects,” said Ruben. “I wouldn’t be able to see a finished physical effect practically until the day we were ready to shoot it. That was a rough way for both of us to work. I was disappointed some times, and I’m sure he was disappointed in the way I was shooting things, although at no time can I remember him making specific suggestions. I think that the main thing I would change if I were to do it again, and I wouldn’t mind working with Craig again.

youtube

Dreamscape (1984) Music by Maurice Jarre 01.DREAMSCAPE 2:58 02.THE JOURNEY 4:22 03.FIRST EXPERIMENT 1:55 04.SUSPENSE 2:09 05.JEALOUSY MERRY-GO ROUND 2:56 06.THE SNAKEMAN 1:08 07.ENTERING THE NIGHTMARE 4:17 08.LOVE DREAMS 4:10

REFERENCES and SOURCES

Twilight Zone v04 n01_ Fangoria 44 Fangoria 27 Fangoria 34 Fangoria 39 Cinefantastique v15 n02

Dreamscape (1984) Retrospective SUMMARY Alex Gardner (Dennis Quaid) is a psychic who has been using his talents solely for personal gain, which mainly consists of gambling and womanizing.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

DREAMSCAPE (1984) - Episode 202 - Decades of Horror 1980s

“Mm, I see. So, Jane, what you do here, in effect, is count boners.” Will one hand be enough? You know. The fingers. Will the fingers on one hand be enough for counting? Join your faithful Grue-Crew – Chad Hunt, Bill Mulligan, Crystal Cleveland, and Jeff Mohr – as they dream a little dream with you and the star-packed cast in Dreamscape (1984).

Decades of Horror 1980s Episode 202 – Dreamscape (1984)

Join the Crew on the Gruesome Magazine YouTube channel! Subscribe today! And click the alert to get notified of new content! https://youtube.com/gruesomemagazine

A man who can enter and manipulate people’s dreams is recruited by a government agency to help cure the President of the United States of his nightmares about nuclear war but stumbles upon an assassination plot

Director: Joseph Ruben

Writers: David Loughery, Chuck Russell, Joseph Ruben (screenplay); David Loughery (story)

Music: Maurice Jarre

Cinematography: Brian Tufano

Film Editing: Richard Halsey

Special Effects & Makeup:

John Eggett (special effects coordinator)

Craig Reardon (special effects)

David Robert Cellitti (special makeup effects artist)

David B. Miller (special makeup effects)

Visual Effects:

Jim Aupperle (stop-motion visual effects supervisor)

James Belohovek (miniature constructor)

Beverly Bernacki (optical lineup)

Stephen Czerkas (stop-motion crew & snakeman model builder) (uncredited)

Linda Drake (stop-motion crew) (as Linda Obalil)

Ernest Farino (stop-motion crew) (as Ernest D. Farino)

Rocco Gioffre (matte artist)

James Hagedorn (optical printer operator) (as James R. Hagedorn)

Pete Kozachik (stop-motion crew)

Peter Kuran (visual effects creator)

Kevin Kutchaver (special photography)

Dennis Pies (dream tunnel effects created by)

R.J. Robertson (rotoscope animation)

Paul Sheppeck (additional matte paintings)

Susan Turner (miniature supervisor) (as Susan K. Turner)

Cast

Dennis Quaid as Alex Gardner

Max von Sydow as Dr. Paul Novotny

Christopher Plummer as Bob Blair

David Patrick Kelly as Tommy Ray Glatman

Kate Capshaw as Jane DeVries

George Wendt as Charlie Prince

Eddie Albert as The President

Peter Jason as Roy Babcock

Chris Mulkey as Gary Finch

Larry Gelman as Mr. Webber

Cory Yothers as Buddy

Redmond Gleeson as Snead

Jana Taylor as Mrs. Webber

Dreamscape is a Decades of Horror 1980s double-tap, first covered in episode 100 by Doc Rotten, Christopher G. Moore, and Thomas Mariani. This time around, Dreamscape is Bill’s pick and he was sucked in by the glowing nunchucks in ads. Although the cast is great, it doesn’t hold up as much as Bill wishes it did and it is far too obvious who the bad guys are. Having said that, it is still a very 80s movie and he would like to see it remade.

Chad thought Dreamscape was great at the time and he still enjoys it even though not everything holds up. In his view, it was hard to pull off everything they were trying to incorporate with the budget they had to work with it. On the other hand, Crystal thinks Dreamscape holds up just fine and she rewatches frequently. Even so, she too would like to see it remade. Jeff still really, really likes it and loves the melding of stop motion animation and other practical effects. He doesn’t appreciate Dennis Quaid’s girl-killer smile but otherwise thinks the cast is incredible.

Regardless of whether or not you’re in the “holds up” or “doesn’t hold up” camps, Dreamscape is a fun 80s flick that tries hard to be a lot of things. At the time of this writing, it’s available to stream from Tubi and Kanopy, and on physical media as a Collector’s Edition Blu-ray from Shout Factory.

Every two weeks, Gruesome Magazine’s Decades of Horror 1980s podcast will cover another horror film from the 1980s. The next episode’s film, chosen by Crystal, will be Howling II: … Your Sister Is a Werewolf (1985), also known as Howling II: Stirba – Werewolf Bitch. Discussing this masterpiece should be howling good fun. …sorry.

Please let them know how they’re doing! They want to hear from you – the coolest, grooviest fans: leave them a message or leave a comment on the gruesome Magazine Youtube channel, on the website or email the Decades of Horror 1980s podcast hosts at [email protected]

Check out this episode!

0 notes

Text

What Makes Hiking Different from Trekking?

Christopher C. “Chris” Babcock, MD, DMD, is an accomplished dental and medical professional in Louisville, Kentucky, with over 20 years of experience. Dr. Babcock holds a BSc in biology from Indiana University and a DMD and MD from the University of Louisville. Christopher C. “Chris” Babcock, MD, DMD, has worked at Louisville Oral Surgery and Dental Implants for over 5 years. In his spare time, he likes to go hiking.

Hiking and trekking are popular outdoor activities that involve walking through natural landscapes. Although they may seem similar, there are several key differences between the two.

Hiking is generally considered to be a leisurely activity that involves walking on well-defined trails or paths for a few hours or a day. Hikers often carry only a small backpack with water, snacks, and basic gear, like a hiking pole and rain poncho. Hiking trails are usually clearly marked and may be found in national parks, nature reserves, and other recreational areas. Hiking is a great way to enjoy nature, get some exercise, and relax.

Trekking, on the other hand, is a more demanding activity that involves multi-day journeys through remote and rugged terrain such as steep mountain passes. Trekkers may also need to cross rivers or glaciers. Trekking trails are often unmarked or poorly marked, and trekkers must rely on maps, compasses, and GPS devices to navigate their way. Trekkers carry larger backpacks with camping gear, food, and other supplies necessary for several days outdoors. Distance covered during a trek can vary widely, from just a few miles to over 20 miles per day, depending on the difficulty of the terrain and the fitness level of the trekker.

Another key difference between hiking and trekking is the level of physical fitness required. Hiking can be enjoyed by people of all fitness levels, while trekking requires a higher level of physical fitness and endurance.

0 notes

Text

Which Deaths Are not Covered by Life Insurance?

Dr. Christopher C. "Chris" Babcock is a respected authority in the field of oral and maxillofacial surgery and an MD and DMD graduate from the University of Louisville. Since 2018, Christopher C. Babcock, MD, DMD, has been a surgeon at Louisville Oral Surgery and Dental Implants. He also has a career in the financial world, where he counsels people on the value of disability and life insurance.

Life insurance is an essential part of financial planning, providing peace of mind to policyholders that their loved ones will be financially secure in the event of their death. However, some deaths may not be covered by life insurance policies.

Suicide is one of the most common exclusions in life insurance policies. Most insurers have a 2-year exclusion period for suicide, meaning that if the policyholder dies by suicide within the first 2 years of the policy's commencement, the death benefit will not be paid out. This exclusion is put in place to prevent people from taking out a policy with the intention of committing suicide.

Death due to risky activities or hobbies may also be excluded from life insurance coverage. Activities like bungee jumping, skydiving, and extreme sports carry a high risk of injury or death, and insurers may view these as a higher risk to cover. Also, when a policyholder is murdered, a life insurance claim can be rejected if the beneficiary is thought to have been involved in the policyholder's death. If the beneficiary is convicted of murder, the insurance company will not pay the death benefit. However, if the beneficiary is acquitted of the crime or is not charged, the death benefit may be paid out.

Finally, deaths resulting from drug or alcohol abuse may also be excluded from life insurance coverage. These deaths are often seen as preventable and may not be covered to discourage risky behavior.

0 notes

Text

When to Harvest Honey

Based in Louisville, Kentucky, Christopher C. Babcock, MD, DMD, delivers patient-focused dental care that includes wisdom teeth removal. Also owning a home on a horse farm, Christopher C. “Chris” Babcock, MD, DMD, maintains beehives.

Timing the harvesting of honey is essential in maintaining a healthy hive. In general, beekeepers aim for the time when a substantial nectar flow has occurred and most of the honey is cured (dried) and capped with wax. Wax capping is the process whereby bees create a protective layer of wax over each cell of a honeycomb, just as one would place a lid over a pot. As summer arrives, checking the progress below the cover of the hive every couple of weeks is recommended. It’s best to wait to harvest until summer winds down and frames contain at least 80 percent of capped honey. Removing honey too soon risks bees stopping production for the season.

Uncapped honey is extractable as long as it’s cured. To see if the honey is cured, turn the frame upside down and shake it gently. If anything leaks from the frame, the syrup is still considered nectar and not ready for harvest. The watery syrup may spoil and ferment if taken before it cures.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Importance of Private Disability Insurance

Kentucky dental surgeon Christopher C. Babcock, DMD, MD, provides care at Louisville Oral Surgery and Dental Implants. Also involved in finance, Dr. Christopher C. (Chris) Babcock, MD, educates people on the importance of life insurance and disability insurance. Disability insurance covers unexpected injury or illness that prevents a return to work. With average disability claims taking more than a year to resolve, mortgage foreclosures occur at a much higher rate after a disability than after a death. Unfortunately, more than a third of full-time workers in the United States do not have adequate coverage to safeguard against a disability. One common misconception is that employers will cover the disability insurance burden. While some companies do offer limited coverage, it is typically short-term and likely to cover only a small amount of the salary. In addition, employer-provided coverage has the drawback of being taxable. By contrast, disability policies procured independently can be tailored to specific needs. Dr. Babcock’s work to ensure that clients receive adequate coverage reflects his own experience of enduring an injury that caused a career altering disability.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Biological Purpose of Wisdom Teeth

An oral and maxillofacial surgeon with Louisville Oral Surgery and Dental Implants in Louisville, Kentucky, Christopher C. “Chris” Babcock, MD, DMD, has decades of clinical experience. One of Dr. Christopher C. Babcock’s areas of expertise as an MD and DMD is wisdom tooth extraction.

Because wisdom teeth often come in crooked, become impacted, or crowd and damage adjacent teeth, approximately 85 percent of people get them removed. Adults without their wisdom teeth see little to no permanent change in their chewing or eating behavior. While people with wisdom teeth use them to chew, people can also chew perfectly well without them.

So why did the ancestors of modern human beings develop the growth of wisdom teeth as an evolutionary trait? First of all, the jaws of these ancestors were more pronounced, allowing more room to fit extra teeth in the mouth. Secondly, their diet of relatively tough items such as raw meat and roots was far harder to chew and grind into swallowable bites. Most anthropologists believe that wisdom teeth provided a couple of extra molars for better chewing before humankind tamed fire to cook, and thereby soften, food.

0 notes

Text

The MouthHealthy Website

Christopher C. “Chris” Babcock, MD, DMD, has established and operated multiple private oral surgery practices over the course of a career that spans two decades. To augment his work as a surgeon with Louisville Oral Surgery and Dental Implants in Louisville, Kentucky, Dr. Christopher C. Babcock holds active membership in several professional societies, including the American Dental Association.

The American Dental Association reaches out to the public with essential and practical oral health information through its award-winning consumer facing website mouthhealthy.org. Recognizing that different people have different dental care needs, MouthHealthy targets specific age groups and demographics with information that is particularly relevant to them.

In addition to providing hygiene guidance and oral health-friendly tips, MouthHealthy offers informative articles full of easy-to-understand scientific facts. The website also allows users to identify ADA-approved dental care products and find an ADA-affiliated dentist near them. MouthHealthy furthers oral health education in the classroom by offering lesson plans, presentations, and other helpful resources to schoolteachers of all kinds.

0 notes

Text

Choosing a Location for a Backyard Beehive

Both a medical doctor (MD) and a doctor of dental medicine (DMD), Christopher C. “Chris” Babcock has been a staff surgeon with Louisville Oral Surgery and Dental Implants since 2018. Outside the office, Dr. Christopher C. Babcock counts beekeeping among his favorite hobbies.

One of first things that aspiring backyard beekeepers should consider is exactly where to place their beehives. This can be a bit tricky. Although bees need plenty of sunlight, they may also benefit from some afternoon shade in very hot environments.

Bees must also have easy access to fresh water. Beekeepers who don’t have a fresh water source on their property should provide that water by filling a shallow receptacle or installing a bubble fountain near their hives.

To prevent stress in the bees, a location should be chosen that is far away from high-traffic areas and doesn’t force bees into contact with people or pets as they travel. Hives should also be kept off the ground to protect them from moisture and predators.

In the northern hemisphere, beehives should be positioned facing south. By providing southern exposure during the winter months, bees are provided with extra sunlight, which can extend their active honey production time.

0 notes

Text

Triads - Fundamental Building Blocks of Chords

Christopher “Chris” C. Babcock, DMD, is a member of the Louisville, Kentucky, medical community and leads a practice that provides various services, from dental extractions to wisdom teeth removal. A music enthusiast, Dr. Christopher C. Babcock plays guitar and is learning to read music.

One of the fundamentals of virtually any guitar technique involves learning triads, or chords made up of three notes. The simplest chords are C, D, G, and Em. They all possess a root, a minor or major third, and a fifth. In addition, that last note can be either perfect, diminished, or augmented.

The easiest way to explain this is that, with a perfect fifth, both notes match the root. A diminished triad has the third and the fifth lowered a half step: for example, a diminished G triad encompasses the notes G, B flat (instead of B), and D flat (instead of D). This creates a sound that tends to come off as dissonant and unsettled to listeners.

By contrast, augmented triads tend to have an exotic, mysterious sound achieved through the fifth raised a half step (or sharpened). An example is the major scale is a C triad chord. This builds upon a root C with an E third and, instead of the standard G, a G sharp on the fifth. Combining such triads in their various permutations can create a surprisingly complex sound, despite the limited palette.

0 notes

Text

A Brief Look at Any-Occupation Disability Insurance

A medical professional with a significant background in oral and maxillofacial surgery, Christopher C. “Chris” Babcock, MD, DMD, practices at Louisville Oral Surgery and Dental Implants. He performs dental implants, extractions, and wisdom tooth removal. Dr. Christopher C. Babcock also has experience as a health and life insurance broker who has lectured extensively about the importance of having both life and disability insurance.

In disability insurance, an any-occupation policy is one that exclusively provides coverage in the event of the inability to do any reasonably-suitable work in relation to the policyholder’s education, age, or experience because of an injury. In another words, the insured can only receive benefits if they suffer a debilitating injury that makes them unable to some kind of job. If an insured turns down a job opportunity for reasons that are unrelated to their health (such as low pay), they will not receive benefits.

For context, consider a heart surgeon who has sustained a hand injury from a car accident. The injury renders the surgeon incapable of performing surgeries because of compromised dexterity. The surgeon can no longer serve in their previous role, but can still work in the medical field as a doctor. Since the surgeon has an alternative job option, they are not categorized as disabled under an any-occupation policy and are not qualified to receive benefits.

0 notes

Text

AAOMS Membership

An experienced oral and maxillofacial surgeon, Christopher C. “Chris” Babcock, DMD, MD, began serving at Louisville Oral Surgery and Dental Implants in 2018. A member of local and national professional organizations, Dr. Christopher C. Babcock, MD, is a member of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS). AAOMS offers over a dozen choices as of 2022, including an annual subscription to the Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, for both new and established professionals in the field. Residents pay no fees or dues their first year, one-third of the fee the second year, two-thirds the third, and full price thereafter. Retired surgeons pay only for the journal subscription plus a fee to receive AAOMS information via mail. Once admitted, members enjoy many benefits. In addition to a spot in the organization’s searchable directory of oral and maxillofacial surgeons, members can search for career information and continuing education resources. New members may attend one AAOMS conference for free within their first three years. They may also take advantage of discounts from companies such as professional liability insurance and classes on relevant skills.

0 notes

Text

What to Expect During Tooth Extraction

The recipient of both an MD and a DMD from the University of Louisville, Dr. Christopher C. "Chris" Babcock has treated and cared for patients at Louisville Oral Surgery and Dental Implants in Louisville, Kentucky. Christopher C. Babcock, MD, performs various dental surgeries such as wisdom tooth removal and dental extraction in this role. Tooth extraction is sometimes recommended by dentists and is typically the last resort if a tooth is severely damaged beyond repair or the mouth is overcrowded with teeth. Dentists try to make the procedure as comfortable as possible for patients. To make tooth extraction painless, a dentist will administer local anesthetics to numb the pain receptors in the pulp cavity and root of the tooth. This way, the patient will not feel pain during the next step of the procedure, which involves gently pulling the tooth back and forth with a pair of medical equipment called forceps. In some cases, a tooth may have become stuck in the gum line, and a minimal incision has to be made in the gum to enable the extraction. Although the patient will not feel pain thanks to the anesthetics, they may feel a slight pressure in their gums during the extraction. After the tooth has been extracted, the socket will be cleaned of any residual tooth or bone fragments. After washing, the gap will be closed (sometimes by stitching the gum tissue). To minimize bleeding, the patient will be asked to firmly bite down on a piece of gauze that has been placed directly above the gap. The dentist will most likely ask the patient to hold an ice pack against their cheek. This prevents the mouth from swelling.

0 notes

Text

Anesthesia Types for Dental Procedures

Practicing with the Louisville Oral Surgery and Dental Implants clinic since 2018, Christopher “Chris” Babcock, DMD, earned his MD and his DMD in dentistry from the University of Louisville. Dr. Christopher C. Babcock, DMD, specializes in oral surgical procedures that may require patient sedation. Dental patients may be sedated due to the length or invasiveness of a procedure, as well as a fear of undergoing dental work. The purpose of sedation is to minimize pain and prevent the patient from becoming overly stressed. The three most commonly used sedation techniques include: Laughing gas: Also known as nitrous oxide, this safe gas is administered to the patient through a face mask. Breathing in the gas produces a calming, euphoric effect that counters anxiety. The patient remains conscious during the procedure. Oral sedation: Another option is a strong medication that the patient takes an hour before the procedure. While the patient is responsive, the sedative may induce amnesia, which can be beneficial for patients with a phobia of dental procedures. Anesthesia: General anesthesia is administered intravenously, and is immediately effective. Since anesthesia renders the patient unconscious, anyone who requires this type of sedation will need a trusted person to bring them home after the procedure.

0 notes

Text

Early Detection Key for Surviving Oral Cancers

Dr. Christopher “Chris” Babcock earned his DMD from the University of Louisville and subsequently completed a residency in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Christopher C. Babcock, MD, performs dental procedures such as wisdom tooth extractions and dental implants. He also conducts screenings and diagnostics for oral diseases. Dentists and oral surgeons routinely scan their patient’s mouths for signs of oral cancer such as thickened tissue, sores, and patches. Routine dental care ensures that oral cancers are discovered early, which is connected to a higher recovery rate. According to a study published in the Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, every year that an oral cancer diagnosis is delayed contributes to a more than two percent increase in the likelihood that the cancer will be fatal. Early-stage cancer is usually treated with localized surgery. Once the cancerous cells are removed, the patient is likely to remain cancer-free. However, advanced oral cancers can spread to the bones or lymph nodes. If the cancer metastasizes, treatment must be more invasive and the chance of survival becomes lower.

0 notes