#David Lindsay 3rd Earl of Crawford

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

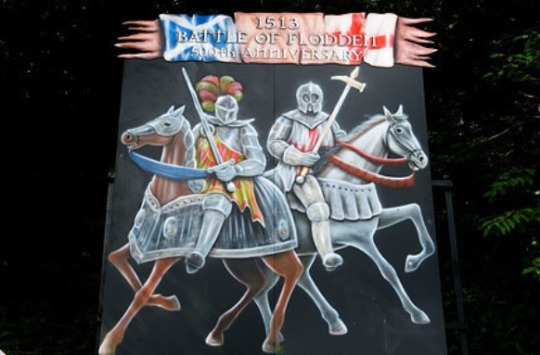

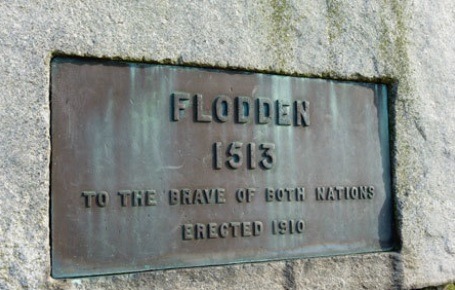

On September 9th 1513 James IV and the flower of Scotland's nobility were killed in battle at Flodden Field.

The Battle of Flodden was essentially a retaliation for King Henry VIII‘s invasion of France in May 1513. The invasion provoked the French King Louis XII to invoke the terms of the Auld Alliance, a defensive alliance between France and Scotland to deter England from invading either country, with a treaty that stipulated that if either country was invaded by England the other country would invade England in retaliation.

The battle took place in Northumberland, just outside the village of Branxton hence the alternative name for the battle, the Battle of Branxton. Prior to the battle, the Scots were based at Flodden Edge, which is how the battle became known as the Battle of Flodden.

The French King sent arms, experienced captains and money to help with the counter attack of England. In August 1513, after King Henry VIII rejected King James IV of Scotland’s ultimatum to either withdraw from France or Scotland would invade England, an estimated 60,000 Scottish troops crossed the River Tweed into England.

Henry VIII had anticipated the French using the Auld Alliance to encourage the Scottish to invade England and therefore had only drawn troops from the south of England and the Midlands to invade France. This left Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey to command the English against the invasion from north of the border. The Earl of Surrey was a veteran of Barnet and Bosworth. His experience became invaluable as this 70 year-old man began to head north assimilating large contingents from the Northern Counties as he headed to Alnwick. By the time he reached Alnwick on the 4th September 1513 he had assembled around 26,000 men.

The outcome of The Battle of Flodden was mainly due to the choice of weapons used. The Scots had advanced in the continental style of the time. This meant a series of massed pike formations. The Scottish armies’ great advantage of using high ground became its downfall as the hilly terrain and ground became slippery underfoot, slowing down the advances and attacks. Unfortunately, the pike is most effective in battles of movement which The Battle of Flodden was not.

Surreys style of using the medieval favourites of the bill and bow against the more Renaissance style of the Scottish with their French pikes proved superior and Flodden became known as the victory of bill over pike!

The English Army led by the Earl of Surrey lost around 1,500 men at the Battle of Flodden but had no real lasting effect on English history, But he repercussions of the Battle of Flodden were much greater for the Scots. Most of the accounts on how many Scottish lives were lost at Flodden conflict, but it is thought to be between 10,000 to 17,000 men. This included a large proportion of the nobility and more tragically our King, below is a list of the most notable men who fell on that day at Branxton.

James IV, King of Scots.

Clergy

Alexander Stewart, Archbishop of St. Andrews and Lord Chancellor of Scotland, natural son of James IV

George Hepburn, Bishop of the Isles and commendator of Arbroath and Iona

William Bunche, Abbot of Kilwinning

Laurence Oliphant, Abbot of Inchaffray

Sir William Knollys, Lord St. John, Lord High Treasurer of Scotland, prior of Torphichen Preceptory.

Earls

Archibald Campbell, 2nd Earl of Argyll

Adam Hepburn, 2nd Earl of Bothwell Lord High Admiral of Scotland

David Kennedy, 1st Earl of Cassilis

William Sinclair, 2nd Earl of Caithness

John Lindsay, 6th Earl of Crawford

William Hay, 4th Earl of Erroll, Lord High Constable of Scotland

Matthew Stewart, 2nd Earl of Lennox

John Douglas, 2nd Earl of Morton, grandson of James I of Scotland

William Graham, 1st Earl of Montrose

William Leslie, 3rd Earl of Rothes

Lords of Parliament

Andrew Stewart, 1st Lord Avondale

William Borthwick, 3rd Lord Borthwick

Alexander Elphinstone, 1st Lord Elphinstone.

Thomas Stewart, 2nd Lord Innermeath

John Maxwell, 4th Lord Maxwell

John Ross, 2nd Lord Ross

George Seton, 5th Lord Seton

John Sempill, 1st Lord Sempill

Robert Erskine, 4th Lord Erskine

Other chieftains, nobles and knights

Robert Arnot of Woodmill. Comptroller of Scotland

Sir Duncan Campbell of Glenorchy

Sir Iain (John) MacFarlane 11th Baron of Arrochar, 8th Chief of Clan MacFarlane

Sir William Cockburn of Langton and his eldest son and heir Alexander

Sir Robert Crawford of Kilbirnie

William Cunningham, 1st Laird of Craigends

George Douglas, Master of Angus

Sir William Douglas of Drumlanrig

Sir William Douglas of Glenbervie

Archibald Graham, 3rd of Garvock – King James' cousin

George Graham, 1st of Calendar

James Henderson of Fordell, Fife; Lord Justice Clerk

Adam Hepburn of Craggis

Sir Alexander Lauder of Blyth, Provost of Edinburgh

Lachlan MacLean, 10th Chief of Clan Maclean

Colin Oliphant, Master of Oliphant

Sir Alexander Ramsay of Dalhousie

Sir John Ramsay of Trarinzeane

Sir William Seton, grandson of James I of Scotland

Sir John Somerville of Cambusnethan

John Hunter 14th Laird of Hunterston

William Hoppringill 1st laird of Torwoodlee

William Wallace 11th of Craigie, 16th of Riccarton

Alexander Guthrie of Kincaldrum, Laird Guthrie of Guthrie

David Guthrie of Kincaldrum, son of Alexander Guthrie of Kincaldrum

David, William, and George Lyon. All three brother-in-laws of Alexander Guthrie of Kincaldrum

Thomas Maule of Panmure, nephew of Alexander Guthrie of Kincaldrum, son of Alexander's sister: Elizabeth Guthrie and her husband, Alexander Maule.

Robert Elliot, 13th Chief of Clan Elliot

John Muirhead, Laird of Muirhead

Pics include the Memorials at Flodden, Selkirk and Coldstream.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lords and Lairds and Ladles

And while I’m on the subject of names and titles, it’s worth pointing out another easily mixed up custom that prevailed until at least the end of the sixteenth century (and probably later, it’s not my specialty).

If you were a nobleman whose surname happened to be ‘Kennedy’ or ‘Douglas’ or ‘Gordon’, that does not mean that you would necessarily be referred to as Lord Kennedy or Lord Douglas or Lord Gordon. Those are very specific titles which belong to specific members of those families.

You MIGHT be referred to as ‘my lord’ as like an honorific, if you were a nobleman or a bishop or an abbot- for example, ‘my lord of Aberdeen’ would be the bishop of Aberdeen while ‘my lord of Murray’ could be either the bishop of Moray (most likely) or the earl of Moray (less likely, but still happened) or, very rarely, a nobleman with the surname Murray. However none of these people would hold the official title ‘Lord Aberdeen’ or ‘Lord Murray’, nor should they be referred to as such.

Sometimes contemporary sources do make mistakes- in particular English diplomats often got mixed up when referring to Scottish nobles, and they might, for example, refer to any male member Kennedy family as ‘Lord Kennedy’, even if they didn’t mean the person who actually held that title. But it does not seem to have been common practice back in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and it certainly isn’t correct to refer to sixteenth century noblemen who didn’t hold a lordship of parliament using those titles in modern historical writing.

I am not au fait with English titles, but it seems that, nowadays, historians generally use the title ‘lord’ much more flexible- I have seen multiple members of the Howard family, alive at the same time, referred to as ‘Lord Howard’ in secondary sources. Whether that was actually the custom in the 16th century I don’t know, but certainly nobody seems to bat an eyelid now.

But as a general (flexible) rule, Lord Hamilton is the man who has been specifically granted the title, not just any nobleman with the surname Hamilton. In 1503, Lord Drummond refers usually to John, 1st Lord Drummond, not any of his sons, and not one of the lairds of Innerpeffray who also bore the surname Drummond. There is a level in the Scottish peerage known as being a ‘lord of parliament’ and these lordships of parliament are an important concept, if sometimes complex.

This is also why laird and lord are not exact synonyms. Yes laird initially stems from the concept of being someone’s lord, and most lords of parliament were also lairds (as were earls and dukes). Sometimes in poetry and prose you will find lord spelt like laird. But in a strict sense, lairds are a lower level of the nobility than the men called ‘Lord’- although lots of lairds, especially those employed at the royal court, could be influential too.

But when speaking plainly Lord Hume does not usually mean the same thing as ‘Laird Hume’. For example Alexander Hume, 3rd Lord Hume, who got his head cut off in 1516 was ‘Lord Hume’- he held the lordship of parliament and, though some might have disagreed, he would probably be thought of as representing the senior line of the family. Several of his kinsmen who bore the surname Hume were lairds though, such as the laird of Cowdenknowes and the laird of Wedderburn. Technically, Lord Hume was a laird too, in the explicit sense of someone who holds lordship over others. But a laird tended to be an ill-defined and lower level of lordship. Calling Lord Hume ‘Laird Hume’ would be like referring to the Duke of York solely by his knightly title Sir Edmund of Langley- he was both, but one of those is his highest title and the other is merely a subsidiary extra.

Hence how James Hamilton, 6th Laird of Cadzow is created, in 1445, James, 1st Lord Hamilton. His son was later created Earl of Arran in 1503. But while the Hamiltons were an important, large, and influential kindred, this did not mean that other male members of the family were Lord Hamilton. Sometimes they might be Lord Hamilton of XXX (a location) or given another title altogether like Lord Paisley (for Claud Hamilton, third son of the 2nd Earl, in 1587).

Alternatively Alexander Gordon, 2nd Lord Gordon, was made Earl of Huntly in 1457. In the sixteenth century we often find the eldest legitimate sons and heirs of the Earls of Huntly bearing the title Lord Gordon. Alternatively, they could be known as the ‘Master’ of Huntly, a common term indicating that the holder was the heir to the estate. But younger sons were not generally referred to as ‘Lord Gordon’ unless they had been granted possession of that lordship by the Earl of Huntly or someone with equal authority- for example, if they were the heir apparent while their older brother was childless. Otherwise they were usually just ‘my lord James Gordon’, or ‘Sir Adam Gordon of Auchindoun’ or ‘Alexander Gordon, the Laird of Lochinver’.

As for their ladies, both lords and lairds’ wives might be referred to as lady, but in slightly different ways. So, had she not already borne a title from her first marriage (Countess of Bothwell), the wife of Alexander, 3rd Lord Hume would have been “Agnes Stewart, Lady Hume”. However the wife of Lord Hume’s distant kinsman David Hume of Wedderburn would be “Alison Douglas, the Lady of Wedderburn”, and the wife of the laird of Cowdenknowes would be perhaps “[Dame] Elizabeth Stewart, [the] Lady [of] Cowdenknowes”. Obviously full names were not always given, and bits and pieces get added and taken away, this was just to give a rough idea.

DAUGHTERS on the other hand are never Lady Hume or Lady Elphinstone, unless they inherited the lordship. Lord Erskine’s wife is Lady Erskine, but his daughters are not all Lady Erskine as well, though they might become ladies of their husband’s title- Margaret Erskine, Lady of Lochleven because she married the laird (not lord) of Lochleven. Though their first name might be put in there to make it easier- Lady/Mistress Barbara Hamilton for example, who then becomes ‘Dame Barbara Hamilton, Lady Gordon’ or Lady Janet Stewart/Mistress Stewart who becomes ‘Dame Janet Stewart, Lady Fleming’ but never just Lady Stewart.

The way people are ‘referred’ to in sources from sixteenth century Scotland is very fluid and flexible (and it doesn’t help that a lot of sources are from English or French writers who didn’t know the difference anyway). But from a modern perspective there are just certain unwritten rules. They’re generally easier to pick up naturally through reading primary and secondary sources than to explain exactly. The concept of a ‘laird’ is often confusing and ill-defined, but a lordship of parliament on the other hand meant something. Lord Crichton was not the same as Lord Crichton of Sanquhar, and certainly not the same as any number of lairds or younger sons who had the surname Crichton but held lands that weren’t associated with the lordship of parliament. Lord Lindsay of Crawford referred to the men who became earls of Crawford, but there was also Lord Lindsay of the Byres, and then a bunch of lairds and knights like Sir David Lindsay of the Mount who shouldn’t strictly be called ‘Lord Lindsay’. Stewart of Innermeath, Stewart of Darnley (later son of the earl of Lennox) and Stewart of Ochiltree all held lordships of parliament, but usually they would be referred to as Lord Innermeath, Lord Darnley, and Lord Ochiltree, even if theoretically they were all Lords Stewart. Then there’s a whole host of minor branches of the Stewart family whose heads can loosely be described as lairds, not lords. And in the plural, for example when referring to the political community, people usually refer to the Scots lords (as in the ‘lords of the parliament’ or ‘lords of the council’) not the Scottish lairds.

And then of course churchmen come along and mess everything up even further, but we won’t get into that.

#It's messy and much easier to just Get once you've done a bit of reading and absorbed the info by osmosis#This is not strictly in line with strict heraldic titles of the 21st century#But if I see one more butchered title in a popular novel or history book I will scream#That being said I know it's a pain so I can answer questions if anybody has any#Can't promise I'll always be 100% correct but there's a good chance

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

☆ ━ ━ OUT OF THE WAY ! can’t you see DAVID LINDSAY, the EARL of CRAWFORD coming this way ? I hear HE is MATICULOUS, but also SKEPTICAL. HE seems to remind everyone of THE SCOTTISH LOWLANDS, TRUE LOYALTY TOWARDS HIS CLAN ALLIES, .&. CRACKING OF WOOD IN A NEWLY STOKED FIRE hopefully one day HE will succeed in HIS ambition to FIND A POTENTIAL HEIR FOR HIS LEGACY, but then again, the court is a dangerous place. one can only hope HE will keep HIS head…

TRIGGERS SUCH AS DEATH & MURDER WILL FOLLOW.

David Lindsay, 8th Earl of Crawford.

Scottish, Loyal to King James V. of Scotland

Based of this dude. X

David is THIRTY SIX - OLD MAN! Born in 1500.1517

He became a father for the first time in 1517.

He named his son Alexander Lindsay, Master Crawford.

In 1536 his own son tried to murder him, when that did not work Alexander, only 19 was disinherited and banned from his home.

His wife died shortly after of a fever and a broken heart.

For now he does not plan on getting married again but is looking for potential brides while also looking for a potential heir

His pride is hurt and he will not trust easily, especially if he will ever have a new born son.

Clan Lindsay is loyal to the Clan Stewart and the only one he will follow, thus given his loyalty to the scottish crown

His rival clans are Clan Gordon and Ogilvy

The sixth Earl of Crawford, his grandfather, was killed at the Battle of Flodden in 1513, while on close attendance to King James IV.

The seventh Earl of Crawford, Alexander William Lindsay of Auchtermonzie held no special place in court whereas David does.

He is disciplined and quite adaptable, very skilled in sword fighting.

Historically he gave his earldom to, David Lindsay of Edzell, a distant cousin who was descended from the 3rd Earl. However, seeing as he is fiercely loyal he did not do that.

H: David died in 1542, but i am turn it around so that his son dies that year.

MORE TO COME SOON

3 notes

·

View notes