#Daniel Davidovsky

Photo

Dagsmóðir

JOANNA BROUK

Majesty Suite: Entrance Of The Queen Of Winter Dawn

PAVEL MILYAKOV, YANA PAVLOVA

Possibility

BERGLIND MARÍA TÓMASDÓTTIR

Lokkur II

HILDEGARD VON BINGEN, J. DUNSTABLE, G. DUFAY, ALMUT TEICHERT-HAILPERIN, KEVIN SMITH, WILFRIED JOCHENS, MARTIN NITZ, HARTMUT DEUTSCH, INSTRUMENTALKREIS HELGA WEBER

Antiphon

ERIC WHITACRE, POLYPHONY, STEPHEN LAYTON

Lux Aurumque

BOSTON MUSICA VIVA, RICHARD PITTMAN, JOSEPH SCHWANTNER, CHARLES IVES, LUCIANO BERIO, MARIO DAVIDOVSKY, DONALD HARRIS

O King (1970)

MORTON FELDMAN

Durations I

MORTON FELDMAN

Rothko Chapel

PEROTINUS

Viderunt Omnes

JOHN ADAMS

Shaker Loops

HAROLD BUDD, BRIAN ENO, DANIEL LANOIS

Late October

THOMAS STANKIEWICZ, ÖRLYGUR STEINAR ARNALDS

Sound Collage

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

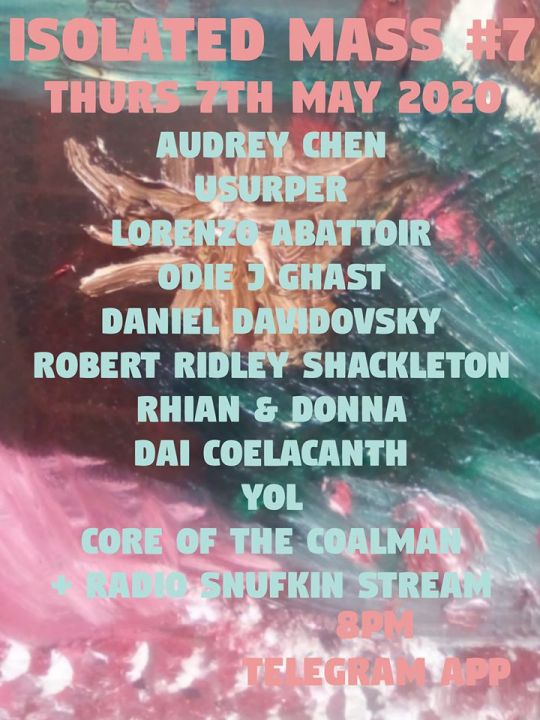

Audrey Chen / Usurper / Lorenzo Abattoir / Odie J Ghast / Daniel Davidovsky / Robert Ridley Shackleton / Rhian & Donna / Dai Coelecanth /Core Of The Coalman / Radio Snufkin at ‘Isolated Mass #7′, Telegram messaging app, The Internet: 7/5/20.

You can find out more about how to “attend” this show, which will happen in real time via the Telegram messaging app, here

#audrey chen#lorenzo abattoir#odie j ghast#daniel davidovsky#robert ridley shackleton#rhian & donnae#dai coelacanth#yol#core of the coalman#radio snufkin#telegram#messaging app#stream#avant#weirdo#free improv#experimental music#electroacoustic#performance#sound poetry#noise#noises#usurper#ALI ROBERTSON#MALCY DUFF#GET READY TO FALL OUT OF LOVE WITH YR SMARTPHONE

0 notes

Text

Escenas de trabajo remoto en casa por el coronavirus

Al cumplirse hoy, 20 de abril, el primer mes del aislamiento social preventivo obligatorio (ASPO) decretado por el Gobierno nacional por la pandemia del coronavirus, te comparto una selección de fotografías de amigos y colegas en la Argentina, publicadas en sus perfiles en Instagram, donde se observan sus lugares de trabajo en sus casas.

(more…)

View On WordPress

#Alejandro Wall#américa latina#Argentina#ASPO#Casa#coronavirus#Daniel Benchimol#Escenas#Federico Ini#Guillermo Tomoyose#Instagram#Irina Sternik#Martina Rúa#Miguel Lederkremer#Santiago do Rego#Sebastián Davidovsky#trabajo#trabajo remoto

0 notes

Text

March 04 in Music History

1678 Birth of Italian composer Antonio Vivaldi in Venice.

1765 Birth of English composer Charles Dibdin.

1776 Birth of English composer and cellist Robert Lindley in Rotherham.

1791 Mozart plays FP of his Piano Concerto No 27. It was his last public performance, in Vienna.

1801 The U.S. Marine Band performed at the inaugural of Thomas Jefferson who was a music lover and violinist. He gave the Marine Band the title "The President's Own." The band has played for every presidential inaugural since.

1809 The U.S. Marine Band performed at first Presidental inaugural ball, for James Madison. The President, First Lady Dolly Madison, and guests heard popular songs and dances of that time.

1819 Birth of German composer and harpist Charles Oberthür in Munich.

1829 Paganini’s debuts in Berlin.

1832 Birth of baritone Ivan Melnikov in St Petersburg.

1857 Birth of Romanian soprano Elena Theodorini.

1858 Birth of Italian soprano Medea Mei-Figner in Florence.

1863 Birth of soprano Ellen Gulbranson.

1875 Death of baritone Louis-Augustin Lemonnier.

1877 Birth of Russian composer Alexander Gedike in Moscow.

1877 FP of Tchaikovsky's ballet Swan Lake at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow.

1878 Death of tenor Napoleone Moriani.

1879 Birth of mezzo-soprano Jeanne Billa-Azema.

1885 FP of Richard Strauss' Horn Concerto No. 1. Gustav Leinhos, soloist, Meiningen Orchestra conducted by Hans Von Bulow.

1888 Birth of Dutch composer Gerard Bunk in Rotterdam.

1895 FP of first and third movements of Mahler's Symphony No. 2 Resurrection. Berlin Philharmonic, composer conducting.

1895 Birth of composer Bjarne Brustad.

1898 Birth of English soprano Dora Labbette in Purley, Surrey.

1904 Birth of Romanian tenor Joseph Schmidt in Rumania.

1906 Birth of baritone Josef Knapp in Klagenfurt.

1910 Death of baritone Leopold Demuth.

1912 Birth of German conductor Ferdinand Leitner.

1913 Death of tenor Giovanni Dimitrescu.

1915 Birth of English violist Cecil Aronowitz in South Africa.

1915 Birth of Spanish-American composer Carlos Surinach in Barcelona.

1921 Birth of Egyptian-American composer Halim El-Dabh in Cairo, Egypt.

1921 FP of Daniel Gregory Mason's Prelude and Fugue for piano and orchestra, in Chicago.

1922 Birth of tenor Roger Gardes in Paris.

1925 Death of German-born Polish composer Moritz Moszkowski at age 70, in Paris.

1926 Death of bass-baritone Theodor Lattermann.

1927 Birth of American composer Robert Di Domenica in NYC.

1927 FP of Mexican composer Julian Carrillo's Concertino by the Philadelphia Orchestra under Stokowski.

1928 Birth of German-American organist and composer Samuel Adler in Mannheim.

1929 Birth of Dutch conductor Bernard Haitink in Amsterdam.

1934 Birth of Argentinian composer Mario Davidovsky.

1934 Birth of baritone Ladislau Konya in Rumania.

1936 Birth of German composer and pianist Aribert Reimann.

1946 Birth of American cellist Ralph Kirschbaum.

1950 Birth of American composer Marilynn Stark in Malone, NY.

1856 Birth of bass-baritone Robert Watkin-Mills.

1959 Birth of American composer Russell Steinberg.

1960 Death of American baritone Leonard Warren.

1965 FP in USAmerica of Ligeti's Poème symphonique for 100 metronomes, in Buffalo, NY.

1968 Birth of American conductor and composer Leanna Sterios.

1969 Birth of Chinese composer Shueh-Shuan Liu in Chang-hua, Taiwan.

1972 Death of tenor Rudolf Petrak.

1988 FP of Domenic Argento's Te Deum for chorus and orchestra. Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra and Schola Cantorum, Thomas Swan conducting.

1971 Birth of Venezuelan composer Sef Albertz.

1992 Death of Hungarian composer Sandor Veress in Bern, Switzerland.

1995 Death of bass-baritone Noel Mangin.

1995 FP of Christopher Rouse's Symphony No. 2. Houston Symphony Orchestra, Christoph Eschenbach conducting.

1999 Death of baritone John Hauxvell.

2003 Death of Italian Mezzo Soprano Fedora Barbieri.

2004 FP of Rolf Wallin´s Act by The Cleveland Orchestra/Welser-Most, Cleveland, OH

0 notes

Text

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Compositores

Giya Kancheli, Christopher Rouse, Michel Legrand, Hans Zender, Dominick Argento , Jacques Loussier, Joao Gilberto, Theo Verbey, Ivo Malec, Mario Davidovsky, Barrington Pheloung, Ben Johnston, Michael Colgrass, Schaeffer, Sven-David Sandström, Ami Maayani, John Joubert, Chou Wen-chung, Ib Norholm, René Samson, Jerry Herman, Jean Chatillon, Alfred Kunz, Thanos Mikroutsikos, Heinz Winbeck, Atli Sveinsson, Frantisek Thuri, Ivan Erob, Gagik Hovunts, Gerhson Kingsley, Thanos Mikroutsikos, Joan Guinjoan, Enrique Iturriaga.

Directores

Maris Janssons, Andre Previn, Raymond Leppard, Jerzy Semkow, Stephen Cleobury, Michael Gielen, Simon Streatfeild, Elio Boncompagni, Werner Andreas Albert, Ján Valach, John Curro, Colin Mawby, Jacques Grimbert, Jean Perisson, Radomil Eliska, Laszlo Heltay, Reto Parolari.

Pianistas: Jörg Demus, Paul Badura-Skoda. Dina Ugorskaja, Daniel Wayenberg, Alexander Tamir, Karen Shaw, Paola Bruni, Márta Kurtág, Dalton Baldwin, Abbey Simon, Ethella Chupryk,

Instrumentistas

Aaron Rosand, Elliot Golub, Marya Columbia, Christian Stadelmann, Jerry Horner, Yossi Gutmann, Uzi Wiesel, Vladimir Orloff, Vagram Saradjian, Anner Bylsma, Michael Grebanier, Susanne Beer, Jean Guillou, Peter Hurford, Peter Noy, Robert Kohnen, Gerd Seiffert, Richard Weiner, Norman Schweikert, Wolfgang Meyer, Alberto Ponce.

Cantantes

Jessye Norman, Hilde Zadek, Heather Harper, Rolando Panerai, Ekkehard Wlaschiha, Erika Sziklay, Margit Laszlo, Charity Sunshine Tillemann-Dick, Marcello Giordani, Felice Schiavi, Joseph Rouleau, Mira Zakai, Spiro Malas, Deborah Cook, Sanford Sylvan, Wilma Lipp, Francisco Casanova, Ann Crumb, Peter Schreier, Theo Adam, Ruth Margaret Putz, Gerald English, Grayston Burgess, Colette Lorand, Joseph Ward, Yang Yang, Helmut Froschauer, Rosemary Kuhlmann, Umberto Grilli, James Christiansen, Miguel Sierra, Art Sullivan, Alle Willis, Patxi Andión, Charlie Karp, Yann Fanch Kemener, Bob Wilber, Camilo Sesto, Eric Morena, Marie Laforet, Dick Rivers, Diahann Carroll, Alain Barriere, Marie Fredriksson.

Directores de escena, cineastas, coreografos, etc:

Jonathan Miller, Johannes Schaaf, Hal Prince, Franco Zeffirelli, Agnes Varda, Pieter Verhoeff, Alex Weil, Jean Claude Brisseau, Eva Kleinitz, Knut Andersen, Ennio Guarnieri, Sebastián Alarcón, Pierre Lhomme, Jukka Virtanen, Guido Levi, Alicia Alonso, Julia Farron, Stanley Donen.

Empresarios, Musicólogos,Críticos Musicales

Victor Hochhauser, Walter Homburger, Naomi Graffman, Peter Noy, Laura Liepins, Paul J Pelkonen, Claude Gingras, Robert Henderson, Roger Covell, Martin Bernheimer, Ferdinando Bologna, Peter Gammond, Vivian Perlis, Clive James, John Simon, Alejandro Planchart, Ferenc Bonis, Scott Timberg.

Cine y teatro

Bruno Ganz, Valentina Cortese, Bibi Andersson, Rutger Hauer, Peter Fonda, Sue Lyon, Anna Karina, Doris Day, Carol Channing, Albert Finney, Carol Lynley, Claudine Auger, Rip Torn, Valery Harper, Sylvia Miles, Tim Conway, Danny Aiello, Anemone, Lee Radziwill, Cameron Boyce, Katherine Helmond, Bruno Scipioni, Sylvia Kay, Peter Zander, Seymur Cassel, Muriel Pavlow, Julie Adams, John Rone, Mario Bernardo, Susan Harrison, Vladimir Etush, Wenche Kvamme, Richard Erdmann, Tom Hatten, Eduardo De Santis, Jospeh Pilato, Alessandra Panaro, Irene Sutcliffe, Barbara Perry, Jane Hayward, Lis Verhoeven, Nancy Holloway, Wendy Williams.

Artes Visuales, Letras, diseñadores, etc.

Carlos Cruz-Diez, Peter Larkin, Emily Mason, Imre Varga, Gerd Jaeger, Luca Alinari, Michael Lyons, Mavis Pusey, Rafael Coronel, Kate Nicholson, Armando Salas, Eduardo Meissner, Gloria Zea, Toni Morrison, I.M. Pei, Karl Lagerfeld, Gloria Vanderbilt, Emanuel Ungaro, Piero Tosi, Verena Wagner-Lafferentz, Christopher ‘Kiffer’ Finzi.

Argentina

Adelaida Negri, Jorge Pérez Tedesco, Cesar Pelli, Osvaldo Romberg, José Martínez Suarez, Eduardo Rovner, Alberto Cortez, Isabel Sarli, Andrew Graham-Yool, Mónica Galán, Ricardo Monti, Graciela Araujo, Leopoldo Brizuela, Analia Gade, Lorenzo Quinteros, Osvaldo Brandi, Santiago Bal, Thelma Tixou, Christian Bach, Beatriz Taibo, Amelita Vargas, Silvia Montanari, Patricia Shaw, Narciso Ibañez Serrador, Lucho Avilés, Beatriz Salomon, Rodolfo Zapata, Fabio Zerpa, Cacho Castaña, Hugo Gambini, Roberto Livi, Juan Martini, Silvina Bosco, Luz Kerz, Roberto Yanés, Guillermo Cervantes Luro, Max Berliner, Malena Marechal, Antonio Caride.

Los Adioses 2019 Compositores Giya Kancheli, Christopher Rouse, Michel Legrand, Hans Zender, Dominick Argento , Jacques Loussier, Joao Gilberto, Theo Verbey, Ivo Malec, Mario Davidovsky, Barrington Pheloung, Ben Johnston, Michael Colgrass, Schaeffer, Sven-David Sandström, Ami Maayani, John Joubert, Chou Wen-chung, Ib Norholm, René Samson, Jerry Herman, Jean Chatillon, Alfred Kunz, Thanos Mikroutsikos, Heinz Winbeck, Atli Sveinsson, Frantisek Thuri, Ivan Erob, Gagik Hovunts, Gerhson Kingsley, Thanos Mikroutsikos, Joan Guinjoan, Enrique Iturriaga.

0 notes

Audio

Experimental Israel - Daniel Davidovsky

ישראל הנסיונית - דניאל דוידובסקי

Language & Narrative

The first time I saw Daniel Davidovsky, our 34th guest on Experimental Israel, perform live I was sure he embodied the uniqueness of character epitomising the improv scene in Israel. With time I discovered two things: that this aforementioned notion was a manifestation of my tendency to romanticise, and the second discovery was that my first intuition was actually right! Davidovsky’s bio is not an anomaly within the Israeli or indeed international improv scene: a saxophone player from the age of 13 grows into an improvising maverick who doesn’t claim one particular setup, stance or style, other than an adherence to what he refers to as “telling a story”.

Musicians that are “connected with themselves”, tells us Davidovsky, must by default have their own language; this, and not the setup, instrument, or style, is the true forefront of their music. A statement that makes complete sense when thinking of Daniel Davidovsky’s practice, as whether he chooses the saxophone, computer, 4 track tape recorder or another provisory setup, he always seems to be talking with the same voice.

I ask Davidovsky to muse with me on the composer/improviser divide, and to that he almost immediately replies: “there is no divide”. Quite a contentious statement to make regarding two musical practices that have engaged in all out war against each other in the not so distant past. “The improviser must follow a compositional thought-process, as with improv too it is the story that is of the essence. A set that didn’t work is a set in which I didn’t tell a good story, or perhaps had nothing to say to start with, or maybe I just got muddled with the story I was hoping to tell. A good improviser is one that exhibits a musical language that easily correlates with his/her personality”. Indeed, Davidovskytakes this notion even further and claims that the raison d’etre of improv as a practice is to allow human expression in the most unconditional form.

When Davidovsky composes, he does so with open scores. This perhaps seems at first like a default, or maybe even expected from someone who dedicates his musical life to chance and the moment. However, with Davidovsky there’s more to this than meets the eye at first: he tells us that when attempting to write a through-composed score, he always gets the feeling that this expression does not convey the experience. In effect, Davidovsky doesn’t choose to write the scores in an open manner, yet he is simply drawn to these visual iterations again and again. “There’s something to be said for individuality, your own story, your behaviour, or your requests of others, and finding the right way to express this in a written score”. It’s as if Davidovsky is expressing that which composers lament on a daily basis, namely the distance between the written score, and the actual music one expects to hear. This divide compels Davidovsky to always search some version of open scoring – according to him, this is the closest visual representation of the experience, and he refers to an experience that isn’t merely acoustic.

“I believe people who practice free music regularly, have attention deficit disorder, and that this practice presents the proper means of expression for them”. A radical statement if it were not said after quite a few installations in which our guests named boredom as one of the key attributes for change in their work, on and off stage. Davidovsky continues and relates this theory to himself by recalling his early days as a young saxophone player. His first teacher came from Klezmer, and so Davidovsky found himself playing Klezmer. Later he moved on to jazz, and davidovsky found himself playing in that idiom. However, he couldn’t shun the feeling that he wasn’t playing from the depths of his soul. He was trying very hard to domesticate these feelings by practicing within given idioms, but as he grew older he couldn’t help but notice that what he really wanted was to break free. As he himself puts it: “I discovered I was trapped in the body of an improviser”. And so, his onward journey took Davidovsky to a musical space devoid of habit, where he immediately felt at home. With Klezmer, he mentions, my fingers were in the lead, whereas I was looking for the leadership of the mind and more so, the heart.

I continue with a query that has interested me, and had therefore found its way into many past installations, but to which I believe I haven’t received an apt reply as of yet: Why are so many people fascinated with improv and live experimentation today (and I am referring to audiences as well as practitioners)? In hopes of stirring a response I cheekily equate this fascination with perversion and voyeurism. Davidovsky disagrees with this prognosis and claims that this fascination stems from a hunger for knowledge. He calls to mind his children, both millennials (a term they themselves had taught him) – they were born into a highly globalized world in which information was much more available compared to the world Davidovsky himself grew up in. And of course, with the accessibility of knowledge comes a greater, perhaps almost insatiable, hunger for more knowledge. “The world of content is changing rapidly, and with it the accessibility to knowledge. I think of things that I myself took half a lifetime to learn and compare this with my kids, both of whom were speaking English before the age of 10”.

But if it hasn’t dawned on you already, I’ll say it outright now: Davidvosky lives in the realm of feeling and emotions. And for him the utmost expression of elation can be found in playing with others that prefer to be emotionally stirred in a similar fashion. Audiences, as he sees it, require this “walk on the precipice” in order to react emotionally, or rather, could not find a way to react emotionally to that which is presented from within a safe and cushioned comfort zone. For Davidovsky, the real skill of improv is to manage to open up that place from within which one’s true language flows. This flow allows the “walk on the edge”. “It’s like riding a bicycle, requiring a delicate balance whilst in motion, but the skill is not in the pedalling or the technique, but rather in being able to recognize the need for an open channel of awareness. The criterion for good improvising is in managing to open up the listener’s associative world. The spontaneous improvising groups’ excitation is in their ability to trace and follow one story, which all participants share”. This story, spoken through their collective language, is the narrative hitting the listeners’ ears, and if something had managed to penetrate through into the listeners’ associative world, then, according to Davidovsky, the story is clear enough, regardless of whether it can be interpreted in different manners.

0 notes

Audio

Experimental Israel - Daniel Davidovsky - ישראל הנסיונית - דניאל דוידובסקי

Language & Narrative

The first time I saw Daniel Davidovsky, our 34th guest on Experimental Israel, perform live I was sure he embodied the uniqueness of character epitomising the improv scene in Israel. With time I discovered two things: that this aforementioned notion was a manifestation of my tendency to romanticise, and the second discovery was that my first intuition was actually right! Davidovsky’s bio is not an anomaly within the Israeli or indeed international improv scene: a saxophone player from the age of 13 grows into an improvising maverick who doesn’t claim one particular setup, stance or style, other than an adherence to what he refers to as “telling a story”. Musicians that are “connected with themselves”, tells us Davidovsky, must by default have their own language; this, and not the setup, instrument, or style, is the true forefront of their music. A statement that makes complete sense when thinking of Daniel Davidovsky’s practice, as whether he chooses the saxophone, computer, 4 track tape recorder or another provisory setup, he always seems to be talking with the same voice.

I ask Davidovsky to muse with me on the composer/improviser divide, and to that he almost immediately replies: “there is no divide”. Quite a contentious statement to make regarding two musical practices that have engaged in all out war against each other in the not so distant past. “The improviser must follow a compositional thought-process, as with improv too it is the story that is of the essence. A set that didn’t work is a set in which I didn’t tell a good story, or perhaps had nothing to say to start with, or maybe I just got muddled with the story I was hoping to tell. A good improviser is one that exhibits a musical language that easily correlates with his/her personality”. Indeed, Davidovskytakes this notion even further and claims that the raison d’etre of improv as a practice is to allow human expression in the most unconditional form.

When Davidovsky composes, he does so with open scores. This perhaps seems at first like a default, or maybe even expected from someone who dedicates his musical life to chance and the moment. However, with Davidovsky there’s more to this than meets the eye at first: he tells us that when attempting to write a through-composed score, he always gets the feeling that this expression does not convey the experience. In effect, Davidovsky doesn’t choose to write the scores in an open manner, yet he is simply drawn to these visual iterations again and again. “There’s something to be said for individuality, your own story, your behaviour, or your requests of others, and finding the right way to express this in a written score”. It’s as if Davidovsky is expressing that which composers lament on a daily basis, namely the distance between the written score, and the actual music one expects to hear. This divide compels Davidovsky to always search some version of open scoring – according to him, this is the closest visual representation of the experience, and he refers to an experience that isn’t merely acoustic.

“I believe people who practice free music regularly, have attention deficit disorder, and that this practice presents the proper means of expression for them”. A radical statement if it were not said after quite a few installations in which our guests named boredom as one of the key attributes for change in their work, on and off stage. Davidovsky continues and relates this theory to himself by recalling his early days as a young saxophone player. His first teacher came from Klezmer, and so Davidovsky found himself playing Klezmer. Later he moved on to jazz, and davidovsky found himself playing in that idiom. However, he couldn’t shun the feeling that he wasn’t playing from the depths of his soul. He was trying very hard to domesticate these feelings by practicing within given idioms, but as he grew older he couldn’t help but notice that what he really wanted was to break free. As he himself puts it: “I discovered I was trapped in the body of an improviser”. And so, his onward journey took Davidovsky to a musical space devoid of habit, where he immediately felt at home. With Klezmer, he mentions, my fingers were in the lead, whereas I was looking for the leadership of the mind and more so, the heart.

I continue with a query that has interested me, and had therefore found its way into many past installations, but to which I believe I haven’t received an apt reply as of yet: Why are so many people fascinated with improv and live experimentation today (and I am referring to audiences as well as practitioners)? In hopes of stirring a response I cheekily equate this fascination with perversion and voyeurism. Davidovsky disagrees with this prognosis and claims that this fascination stems from a hunger for knowledge. He calls to mind his children, both millennials (a term they themselves had taught him) – they were born into a highly globalized world in which information was much more available compared to the world Davidovsky himself grew up in. And of course, with the accessibility of knowledge comes a greater, perhaps almost insatiable, hunger for more knowledge. “The world of content is changing rapidly, and with it the accessibility to knowledge. I think of things that I myself took half a lifetime to learn and compare this with my kids, both of whom were speaking English before the age of 10”.

But if it hasn’t dawned on you already, I’ll say it outright now: Davidvosky lives in the realm of feeling and emotions. And for him the utmost expression of elation can be found in playing with others that prefer to be emotionally stirred in a similar fashion. Audiences, as he sees it, require this “walk on the precipice” in order to react emotionally, or rather, could not find a way to react emotionally to that which is presented from within a safe and cushioned comfort zone. For Davidovsky, the real skill of improv is to manage to open up that place from within which one’s true language flows. This flow allows the “walk on the edge”. “It’s like riding a bicycle, requiring a delicate balance whilst in motion, but the skill is not in the pedalling or the technique, but rather in being able to recognize the need for an open channel of awareness. The criterion for good improvising is in managing to open up the listener’s associative world. The spontaneous improvising groups’ excitation is in their ability to trace and follow one story, which all participants share”. This story, spoken through their collective language, is the narrative hitting the listeners’ ears, and if something had managed to penetrate through into the listeners’ associative world, then, according to Davidovsky, the story is clear enough, regardless of whether it can be interpreted in different manners.

#Bicycle#Daniel Davidovsky#Electronic#Experimental Israel#Free Improvisation#ישראל הנסיונית#אופניים#דניאל דוידובסקי#Ophir Ilzetzki

0 notes