#CourtTranslation

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Hello, I am Certified Vietnamese Court Interpreter_Kristie Thanh Nguyen and I am based in Fountain Valley, CA. I have been in this business for six years and in addition to being a court interpreter, I am also a certified probate real estate specialist, licensed real estate agent, certified life coach, and law student in her third year with an AA degree in Paralegal Studies.

I am one of 49 certified Vietnamese court interpreters in California and one of only 10 in the southern part of the state. Being able to interpret and translate from English to Vietnamese and vice-versa allows me to provide my clients with court translation and interpretation, immigration services, and other legal services. From real estate listings and divorce cases to bankruptcy and deportation cases, you can count on me to ensure that you come out of your situation on top. All clients have access to free resources and free one-on-one consultations so that I can prepare a thoroughly solid case that results in a win for my client.

No matter what your situation may be, I will work hard to make sure that you win your case. For more information about my services, please contact me at Certified Vietnamese Court Interpreter_Kristie Thanh Nguyen today!

https://fountainvalleycourttranslator.com

#CourtTranslation#CertifiedVietnameseTranslator#VietnameseTranslator#ImmigrationServices#ProbateRealEstate#Bankruptcy#CourtInterpreting#CertifiedVietnameseInterpreter#CertifiedVietnameseCourtInterpreter#VietnameseInterpreter#LegalServices#DeportationCases#ProbateListingAgent#RealEstateListings#DivorceCases

1 note

·

View note

Photo

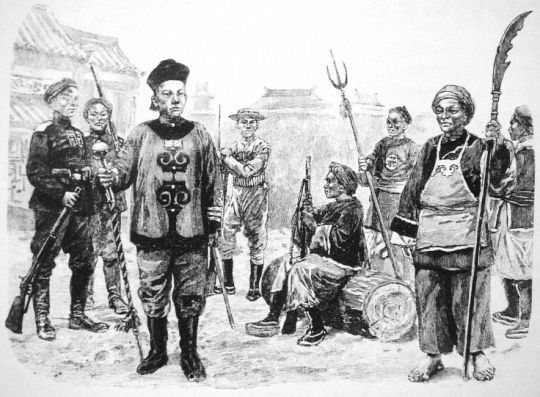

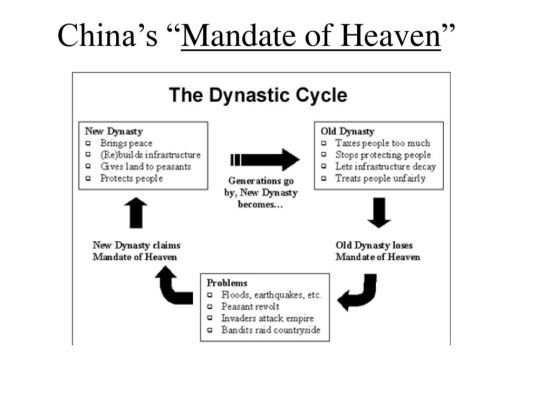

TO TOPPLE A DYNASTY: KUNG FU REBELS AND THE CYCLE OF HISTORY

“The last time China’s government collapsed was just over 100 years ago, when the Qing Dynasty fell after almost four centuries of rule. The fall didn’t happen in a day, ranging instead over a century of unrest and violence that began around 1850 and ended in 1950 when the Communist Party consolidated rule over most of the country.”

“The martial arts played a critical, prominent role in the rebellions and warfare that tore the nation apart and eventually toppled the Emperor. Four rebellions in particular put the role of the martial artist in times of social unrest into perspective, and also help place the current martial arts infrastructure in China into stark contrast with the institutions that existed 100 years ago.”

Those rebellions are the Red Turban or “Opera Rebellion” (1854 - 1855), the Red Spears Uprising (powerful in the 1920s and 30s), The Boxer Rebellion (1899 - 1901) and the most destructive civil war in the history of mankind, the Taiping Rebellion (1850 - 1864).”

“Officials and martial arts societies in Guangzhou at this time were faced with a choice: join the rebels and chaos or join the Imperials and order. The elites and their martial retainers chose order. After that choice was made, the rebellion was crushed and the elites went on a violent purge of the underclasses, slaying up to a million boatmen, wanderers, broke people, performers, unaffiliated thugs and martial artists. The Opera Rebellion demonstrates the tendency of the Chinese elite to use and exploit the martial element of society when needed, and destroy and pacify it when not.”

”The Opera Rebellion was one of the first steps towards solidifying the relationship between the State and martial artists, one in which kung fu societies would either serve the government or be annihilated. China’s government still uses thugs whenever they need them. The attempted suppression of the Occupy Central movement in Hong Kong through Triads and other gangsters was widely thought to be a Beijing ploy. It certainly fits in with the old tactics that have worked for centuries and the way the whole thing went down in Hong Kong smacks of how the Chinese central government does their thing.”

“The Red Spear Society in Henan Province was perhaps the largest pure martial arts uprising of its time, although “uprising” is not entirely accurate. The Red Spears (1916 - 1949) were a response to the complete breakdown of social, economic, and political institutions in north-central China. Famines, warlordism, corruption, banditry along every road...The Red Spears were essentially groups of more or less trained martial artists who worked with local elites and landlords to establish a semblance of order. But what in fact happened was just banditry in a more organized fashion.”

“The Red Spears and their many offshoots and enemies “ruled” Henan until the Northern Expedition of 1928 by the Chinese Nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek re-established some kind of government control over the area. This is the same expedition that resulted in the razing of the Shaolin Temple and the destruction of several rebel bands, but didn’t actually maintain control. The area would be the demesne of martial artists armed with spears, swords, bucklers, muskets and the odd rifle for another 20 years, until the Communists assumed strong central control over China.”

“As with the Opera Rebellion, the authorities didn’t immediately annihilate the martial bands and their leaders. They had a choice. Go home and be obedient citizens, or be destroyed. The authorities eventually co-opted many of the societies affiliated (or opposed to) the Red Spears and established a whole new set of institutions to channel and control the martial element within Chinese society. Sports universities and wushu associations, for example, replaced the clans, fiefs, and martial arts schools that formed the core of the martial infrastructure in the 19th century. Anyone willing to enter this new path for the martial artist was welcome, those who did not were purged.”

“Martial arts in China is a part of society that cannot be burned out, purged into oblivion, or ignored. No matter what happens to kung fu in China, it has always popped back up. It is still commonplace today for business-owners in a dispute to call upon the kung fu guys they know for muscle. Guns are hard to come by in China, so most of the street level fighting is done with fists, bottles, or knives. In a corrupt society ruled by class and social distinctions more than by the rule of law, kung fu has its place. The Communist Party understands this and has done a solid job of channeling kung fu into the movies, sports, and security apparatus. That will work as long as the authorities maintain a monopoly on dispute resolution and violence. When the government does not hold this monopoly, the old violent cycle of rebellion and disunity follows.”

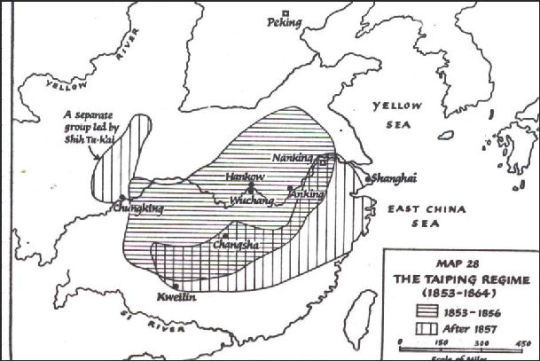

“More than 20 million people died during the Taiping Rebellion, history’s nastiest and most destructive civil war. The war lasted for two decades. To try and give this perspective, about 600,000 people died during the American Civil War, which was raging at the same time.”

“The Taiping Rebellion was born in a perfect storm of widespread economic hardship, official malfeasance and weakness, the rise of regional bandit and kung fu societies, and religious heterodoxy. Geopolitically China was in bad shape, having lost the First Opium War and about to lose the Second. Socially, the entire country was a patchwork of regional governors working within constantly shifting alliances involving a hundred thousand different societies, organizations, gangs, associations and what not ... an unstable quilt of betrayal and greed that operated with impunity beneath the charade of paternal Imperial rule.”

“The spark that lit all of this dry wood into a 20 year conflict was a self-proclaimed prophet, Hong Xiuquan, who foretold the fall of the ethnic Manchus and their Qing Dynasty to an alliance of quasi-Christian ethnic Han rebels who would usher in a new modern era for China. The martial arts societies that grew and flourished all over China as the Qing’s power waned made up a large part of the Taiping armies. The martial element within society formed under a cultish banner to assault the status quo in the hopes of creating a new society. Their new society was based ostensibly on equality and the abolition of old Imperial accoutrements like Confucianism, Buddhism, and the idea of a Dynasty altogether.”

“Hong and his followers failed and were eventually crushed. Their failure came about mostly due to Western powers who lent their aid to the Qing Dynasty at a critical juncture, the Battle of Shanghai, and then helped form a modern army that could take on and defeat the Taiping forces. After the Taiping capital at Nanjing was taken, the Imperials spent another 10 years hunting down the rest of the Taiping forces before the threat was permanently extinguished.”

“The Communists have drawn many lessons from the Taiping Rebellion: Crush any heterodox religious movement before it can grow. Keep the “prophets” separated from the commoners who make up the core of every rebel army that ever existed. Co-opt and control the martial arts and never allow the three (commoners, prophets, martial artists) to combine into a powerful anti-government force.”

“The Taiping Rebellion was, among many other things, such a combination, but where the Taiping rebels failed, the Communists succeeded. A combination of commoners, martial elements, and the cultish power of Marx embodied in Mao eventually did erase the dynasty and establish a new society, also based on ideals any commoner could get behind. The Communist Party has since rehabilitated the Taiping Rebellion, and placed those rebels within the context of a century long struggle to throw off the Imperial yoke and gain freedom for the proletariat.”

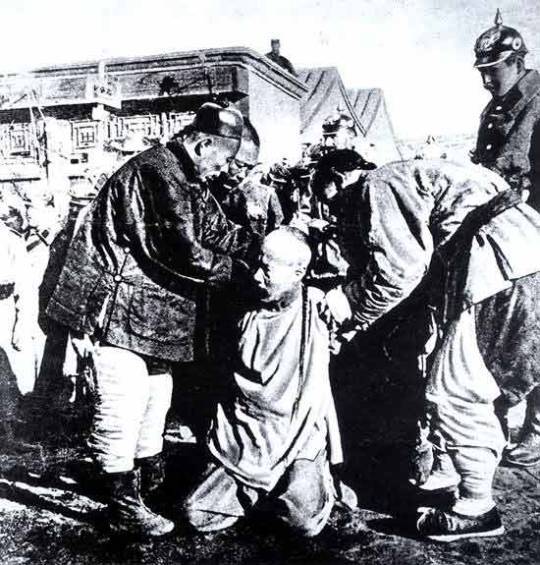

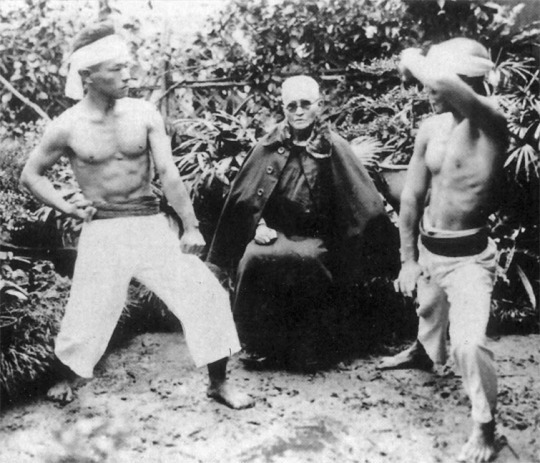

“The Boxers were a band of “Righteous and Harmonious Fists” who called for the expulsion of foreigners and the restoration of the Imperial order. For two years they split the Qing government in two, with the pro-Boxer faction including the Empress Dowager Cixi calling for all out war against the foreign powers on one side, and conciliatory diplomats on the other. In chaotic battles involving irregulars armed with swords as well as Imperial soldiers armed with the most modern cannons at the time, the Boxers and their allies defeated foreign armies and besieged foreign legations within Beijing. The uprising also led to widespread killings across China, mainly targeting Christians and missionaries.

The Qing were betrayed by regional warlords who refused the call to war against the foreigners, and after protracted battles in Beijing and Tianjin, the rebellion was put down by the Eight Nation Alliance (Western powers)...ordered the Qing to pay reparations (around $61 billion in modern terms) and execute many top officials.”

“And for much of Chinese history, that’s what martial artists tended to be. Performers and bodyguards, dispute-settlers and paragons of idealistic virtue. It’s only when the government stumbles, leaving a vacuum, that kung fu people become the type of force that step in and help keep order, or help topple a dynasty. In that sense, it doesn’t matter if the kung fu people of today are rebellious or obedient, it matters more that the government maintains a monopoly on force and justice. Once that monopoly is challenged, the old cycle of history tells us that violence is right around the corner.”

(via To Topple a Dynasty: Kung Fu Rebels and the Cycle of History | FIGHTLAND)

Chinese names in traditional Chinese family culture

“Within each family system, besides the common family name, descendants often specify another common character in their given names for each generation. This common character in given name is called the "Spreading Character", which is an indication of the person's generation within the family system.The Spreading Character can be either the first character or the second character of the given name.”

Generational (spreading) names that are shared among brothers and cousins may be based on (or a variant of) the mother’s or grandparent’s family name, usually if the clan has higher status than the father’s family name.

Generational name

“Generation name, variously zibei or banci, is one of the characters in a traditional Chinese given name, and is so called because each member of a generation (i.e. siblings and paternal cousins of the same generation) share that character. Where used, generation names were usually given only to males.

Generation names may be the first or second character in a given name. Normally this position is consistent for the associated lineage. However some lineages alternate its position from generation to generation. This is quite common for Korean names. Sometimes lineages will also share the same radical in the non-generation name.”

Korean name

"During the Three Kingdoms period, native given names were sometimes composed of three syllables like Misaheun (미사흔) and Sadaham (사다함), which were later transcribed into hanja (未斯欣, 斯多含). The use of family names was limited to kings in the beginning, but gradually spread to aristocrats and eventually to most of the population.[25]

According to the chronicle Samguk Sagi, family names were bestowed by kings upon their supporters...For men of the aristocratic yangban class, a complex system of alternate names emerged by the Joseon period. On the other hand, commoners typically only had a first name.[17] Surnames were originally a privilege reserved for the yangban class, but members of the middle and common classes of Joseon society frequently paid to acquire a surname from a yangban and be included into a clan.”

“The initial sound in "Kim" shares features with both the English 'k' (in initial position, an aspirated voiceless velar stop) and "hard g" (an unaspirated voiced velar stop). When pronounced initially, Kim starts with an unaspirated voiceless velar stop sound; it is voiceless like /k/, but also unaspirated like /ɡ/. As aspiration is a distinctive feature in Korean but voicing is not, "Gim" is more likely to be understood correctly. "Kim" is used nearly universally in both North and South Korea.[40]

In English publications, usually Korean names are written in the original order, with the family name first and the given name last. This is the case in Western newspapers. Koreans living and working in Western countries have their names in the Western order, with the given name first and the family name last. The usual presentation of Korean names in English is similar to those of Chinese names and differs from those of Japanese names, where they, in English publications, are usually written in a reversed order with the family name last.”[43]

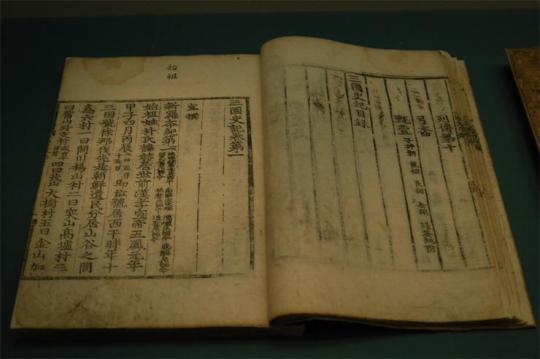

Samguk sagi

“Samguk sagi (삼국사기, 三國史記, History of the Three Kingdoms) is a historical record of the Three Kingdoms of Korea: Goguryeo, Baekje and Silla... the Records of the Grand Historian, this work was released circa 100 BCE under the more modest title of Shǐjì 史記, i.e. Scribe's Records. By allusion, Kim Busik called his own work 三國史記, i.e. Samguk sagi, where Sagi (nowadays 사기) was the Korean reading of the Chinese Shǐjì.[1]

"Native heritage" is primarily interpreted by the Samguk sagi to mean "Three Kingdoms heritage" brings us to the work’s ostensibly broader purpose, and that was to promote Three Kingdoms...as the orthodox ruling kingdoms of Korea, and to thus solidify the legitimacy and prestige of the Goryeo state, as the Three Kingdoms’ rightful successor. In this way it helped to confer the idea of zhengtong 正統, or "orthodox line of succession", upon the new dynasty. It was with just such intent that Goryeo's King Injong tapped Kim Busik to compile the history of the Three Kingdoms. Goryeo’s quest, through the writing of the Samguk sagi, to secure its legitimacy and establish its continuation of the "mantle of authority" (or Mandate of Heaven) from the Three Kingdoms.”

Manchu name

“Like the Mongols, the Manchus were simply called by given name but they had their own clan names (hala in Manchu)...The Comprehensive Book of the Eight Manchurian Banners' Surname-Clans (八旗滿洲氏族通譜 Baqi Manzhou Zhizu Tongpu), compiled in the middle 18th century, records many Manchu clan names. Among more than a thousand names, about 600 names are the Manchus'.

Gioro, a major clan name, is the one of the few hala that has various variants such as Irgen, Silin and Šušu, possibly to distinguish from the imperial family name Aisin-Gioro. Since the mid-to-late Qing Dynasty, Manchus have increasingly adopted Han Chinese surnames, and today, very few Manchus bear traditional Manchu family names.”

Naming taboo

“A naming taboo is a cultural taboo against speaking or writing the given names of exalted persons in China and neighboring nations in the ancient East Asian cultural sphere.

The naming taboo of the state (国讳; 國諱) discouraged the use of the emperor's given name and those of his ancestors...The strength of this taboo was reinforced by law; transgressors could expect serious punishment for writing an emperor's name without modifications. In 1777, Wang Xihou in his dictionary criticized the Kangxi dictionary and wrote the Qianlong Emperor's name without leaving out any stroke as required. This disrespect resulted in his and his family's executions and confiscation of their property.”[1]

Eight Banners

“The Eight Banners were administrative/military divisions under the Qing dynasty into which all Manchu households were placed. In war, the Eight Banners functioned as armies, but the banner system was also the basic organizational framework of all of Manchu society.

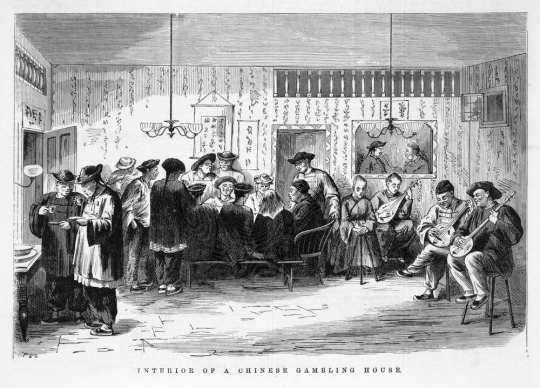

Although the banners were instrumental in the Qing Empire takeover of China proper in the 17th century from the Ming dynasty, they began to fall behind rising Western powers in the 18th century. By the 1730s, the traditional martial spirit had been discarded, as the well-paid Bannerman spent their time gambling and theater going. Subsidizing the 1.5 million men, women and children in the system was an expensive proposition, compounded by embezzlement and corruption.

In the 19th century, the Eight Banners and Green Standard troops proved unable to put down the Taiping Rebellion and Nian Rebellion on their own. Regional officials like Zeng Guofan were instructed to raise their own forces from the civilian population, leading to the creation of the Xiang Army and the Huai Army, among others. Along with the Ever Victorious Army of Frederick Townsend Ward, it was these warlord armies (known as yongying) who finally succeeded in restoring Qing control in this turbulent period.”

“During the Boxer Rebellion, 1899–1901, 10,000 Bannermen were recruited from the Metropolitan Banners and given modernized training and weapons...Many Manchu Bannermen in Beijing supported the Boxers and shared their anti-foreign sentiment.[50] The Manchu Bannermen were devastated by the fighting during the Boxer Rebellion, sustaining enormous casualties during the war and subsequently being driven into desperate poverty.[51]

By the late 19th century, the Qing Dynasty began training and creating New Army units based on Western training, equipment and organization. Nevertheless, the banner system remained in existence until the fall of the Qing in 1911, and even beyond, with a rump organization continuing to function until the expulsion of Puyi (the former Xuantong emperor) from the Forbidden City in 1924. At the end of the Qing dynasty, all members of the Eight Banners, regardless of their original ethnicity, were considered by the Republic of China to be Manchu.”

Chinese Interpreters in San Francisco

“The Court Interpreter, Moy A. Non, has officiated in numerous cases, but none of his countrymen have sought to molest him. It is a very pretty riddle to solve, and is, to say the least of it, rather suggestive. The Court Interpreter is armed with unlimited power for evil, and it certainly behooves the authorities to leave no stone unturned to replace him with a white man.”

“In several cases where a Caucasian interpreter has been called in, his translations have been contradicted, his knowledge of the Chinese tongue ridiculed, and the Court thereby embarrassed. The Court is powerless to detect fraud in the books of Chinese firms, and is compelled to rely solely upon the translations of a Chinaman whose life would not be worth a nickel were he a stumbling block in the path of the Chinese firms. Those books are produced as evidence that the applicant for debarkation resided here formerly, and it rests altogether with the interpreter whether he gives the Court a true or a false reply. It is humiliating to the last degree to behold the administration of the law placed at the mercy of one whose every instinct despises it, and whose very existence depends upon his perjuring himself to thwart it.”

January 13, 1884, Daily Alta California, San Francisco, California, U.S.A.

What Did Chinatown Leaders Do to Avert Anti-Chinese Violence? Did They Succeed?

“In 19th century New York, the presence of well-connected Chinese figures like Honorary Deputy Sheriff Tom Lee and the pioneering civil rights advocate Wong Chin Foo gave the Chinese community there a very different public image from that of Chinese in Sacramento or San Francisco.

Chinese leaders in the big California cities had different backgrounds than Chinese leaders elsewhere in North America. While in Chicago and New York, community leadership came from merchants and other businessmen, in California it was in the hands of diplomats and high-status scholars brought specially from China to head the various regional associations. Such leaders, legitimized by Chinese law and traditional attitudes, must often have worked effectively among their countrymen. They also could use their high-level connections in China to mobilize the imperial government on the behalf of Chinese in and outside California.”

“In 1886, Chin Gee Hee's close business connections with such figures as Judge Thomas Burke, along with his influence at the Chinese ministry in Washington, was a key factor in persuading the white establishment to intervene against attempts to drive out Chinese residents.”

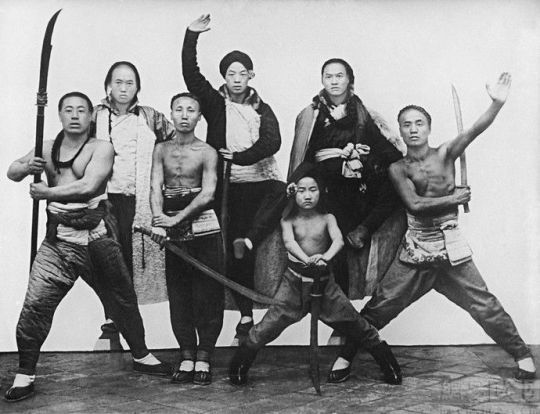

The First Exhibition of Kung Fu and Chinese Martial Arts in America: Brooklyn, 1890

“On February 23, 1890, the following announcement appeared in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

At Robertson’s Gymnasium, corner of Fulton and Orange streets, on Tuesday evening, Ah Giang and [Foo Jung], champion bantam and featherweight fighters of China, will give an exhibition of the manly art of self defense as conducted in their native country.

Although, previously, a few reports of the existence of Kung Fu and styles of Chinese pugilism had appeared in American newspapers, the exhibition at Robertson’s gymnasium appears to be the first demonstration that was open to the public, and was certainly the first such event that attracted any degree of attention in the American print media.”

“It is worth noting that the speaker, Wong Chin Foo (1847-1898), was a noted activist for Chinese American civil rights. He was also a former revolutionary, having attempted to overthrow the corrupt Qing government. He fled to the U.S. in 1873, where he established the Chinese Equal Right League, founded a Chinese-language newspaper, crusaded against vice in New York City’s Chinatown, and survived several assassination attempts by gangsters. At one point, he challenged the San Francisco anti-Chinese journalist Denis Kearney to a duel. Wong also bought a Chinese theater, established a language school and opened a Confucian temple.”

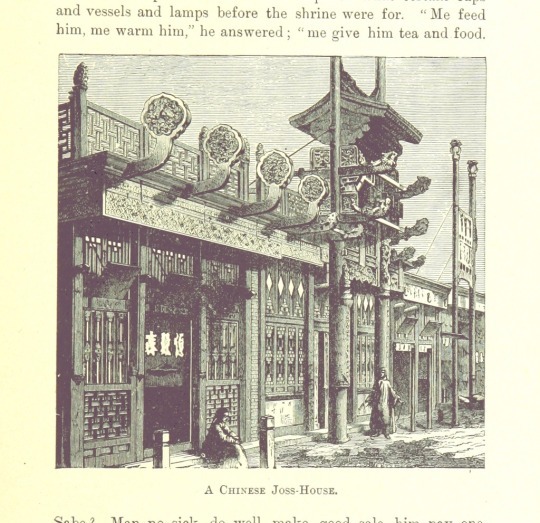

Chinese temple architecture

“Chinese temple architecture refer to a type of structures used as place of worship of Chinese Buddhism, Taoism or Chinese folk religion/Shenism, where people revere ethnic Chinese gods and ancestors.

Gōng (宫), meaning "palace" is a term used for a templar complex of multiple buildings, while yuàn (院) is a generic term meaning "sanctuary" or "shrine".

See Lung Hing Kee & Co. Chinese Joss House 131 1st Avenue, Portland, OR

“An old name in English for Chinese traditional temples is "joss house".[1] "Joss" is an Anglicized spelling of the Portuguese word for "god", deus. "Joss house" was in common use in English in western North America during frontier times, when joss houses were a common feature of Chinatowns. The name "joss house" describes the environment of worship. Joss sticks, a kind of incense, are burned inside and outside of the house.”

A Husband-Wife Team from San Francisco

“The Harvard anthropologist Frederick Ward Putnam, who was a top Fair official and should have known what he was talking about, described them as

“the most prominent Chinese at the fair.” He wrote that Ah Que had been educated by Presbyterian missionaries in San Francisco and that “she is said to be very popular” in that city. As for Wong Ki, Putnam credits him with being “the architect of the Chinese Building and the decorator and designer of the Joss House.”

“Putnam goes on to say that Wong Ki was “a native of Canton, where he spent his youth in studying the peculiar architecture of his country. Arriving at manhood, he concluded to cast his lot with many of his countrymen in California, and there was successful at his trade and also fortunate in meeting the beautiful Ah Que, who is now his devoted wife.”The problem is that Putnam’s captions contradict other sources. Wong Ki certainly was not the most prominent male Chinese at the Fair. Hong Sling and Gee Wo Chan received more publicity, and leading members of the Moy family were more influential. True, one Wong Kee, said to be the richest man in (the Clark Street) Chinatown, was a financial backer of the Chinese Theater and Joss House.”

Wong Kai Kee, Artist and Printer, and His Progressive Wife

The Los Angeles Herald (California) March 15, 1896 As Chinamen See Us

“Kai Kee, the distinguished Chinese artist, has made some pictures of New York life for the readers of the Sunday Journal. Kai Kee has established a little studio at No. 1 Doyers street, where he has decided to settle after his fame and reputation at the Chicago world’s fair. He was sent to the exposition from his native land to superintend the construction of the Chinese government buildings at the fair.”

“He was more than pleased when requested to make some pictures for the Journal. Mr. Kai Kee begins his pictorial impressions of New York life with a sketch of the crowd at the entrance to the Brooklyn bridge. Then he was taken to the menagerie in Central park and given an hour’s opportunity to study the monkey pavilion.”

Keye Luke

“Luk Shek Kee (June 18, 1904 – January 12, 1991) was a Chinese-American film and television actor, technical advisor and artist, he was a founding member of the Screen Actors Guild[1][2] He was known for playing Lee Chan, the "Number One Son" in the Charlie Chan films, the original Kato in the 1939–1941 Green Hornet film serials, Brak in the 1960s Space Ghost cartoons, Master Po in the television series Kung Fu, and Mr. Wing in the Gremlins films. He was the first Chinese-American contract player signed by RKO, Universal Pictures and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and was one of the most prominent Asian actors of American cinema in the mid-twentieth century.”[3]

Shaolin Monastary

“There is evidence of Shaolin martial arts being exported to Japan since the 18th century. Martial arts such as Okinawan Shōrin-ryū (小林流) style of Karate, for example, has a name meaning "Shaolin School"[26] and the Japanese Shorinji Kempo (少林寺拳法) is translated as "Shaolin Temple Fist Method". Other similarities can be seen in centuries-old Chinese and Japanese martial arts manuals.”[27]

Hapkido

“Hapkido is rendered "합기도" in the native Korean writing system known as hangul, the script used most widely in modern Korea. The art's name can also however be written "合氣道" utilizing the same traditional Chinese characters which would have been used to refer to the Japanese martial art of aikido in the pre-1946 period. The current preference in Japan is for the use of a modern simplified second character; substituting 気 for the earlier, more complex character 氣. The character 合 hap means "coordinated", "joining", or "harmony"; 氣 ki describes internal energy, spirit, strength, or power; and 道 do means "way" or "art", yielding a literal translation of "joining-energy-way". It is most often translated as "the way of coordinating energy", "the way of coordinated power", or "the way of harmony.

Although Japanese Aikido and Korean Hapkido share common technical origins, in time they have become separate and distinct from one another. They differ significantly in philosophy, range of responses, and manner of executing techniques. The fact that they share the same Japanese technical ancestry represented by their respective founders practice of Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu, and that they share the same Chinese characters, despite 合 being pronounced "ai" in Japanese and "hap" in Korean, has proved problematic in promoting Hapkido internationally as a discipline with its own set of unique characteristics differing from those common to Japanese martial arts.”

Kido Kwon Association

Aikido

“In Japanese Aiki is formed from two kanji:合 - ai - joining氣 - ki - spirit

The kanji for "ai" is made of three radicals, "join", "one" and "mouth". Hence, "ai" symbolizes things coming together, merging. Aiki should not be confused with "wa" which refers to harmony. The kanji for "ki" represents a pot filled with steaming rice and a lid on it. Hence, "ki" symbolizes energy (in the body).

Thus aiki's meaning is to fit, join, or combine energy. However, care must be taken about the absolute meanings of words when discussing concepts derived from other cultures and expressed in different languages. This is particularly true when the words we use today have been derived from symbols, in this case, Japanese kanji, which represent ideas rather than literal translations of the components.”

“Historical use of a term can influence meanings and be passed down by those wishing to illustrate ideas with the best word or phrase available to them. In this way, there may be a divergence of the meaning between arts or schools within the same art. The characters "ai" and "ki" have translations to many different English words.Historically, the principle of aiki would be primarily transmitted orally, as such teachings were often a closely guarded secret. In modern times, the description of the concept varies from the physical [1] to vague and open-ended, or more concerned with spiritual aspects.

Aiki lends its name to various Japanese martial arts most notably aikido and its parent art, Daito-ryu aiki-jujutsu. These arts tend to use the principle of aiki as a core element underpinning the bulk of their techniques. Aiki is an important principle in several other arts such as Kito-ryu and various forms of kenjutsu.[2]

”

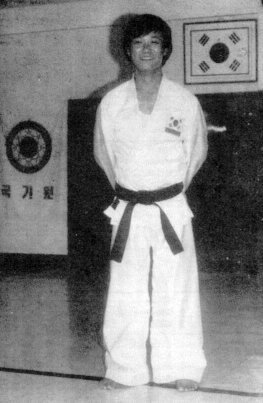

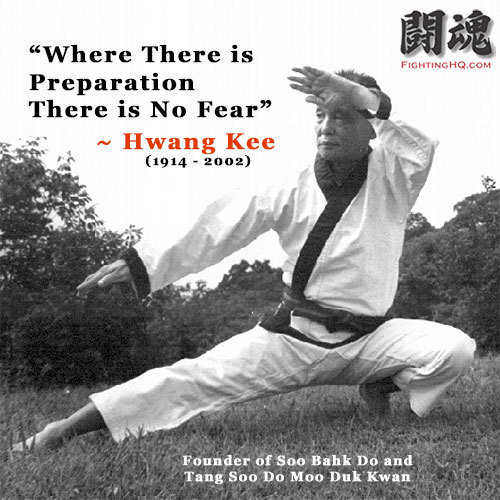

Tang Soo Do

“"Tang Soo Do" (당수도) is the Korean pronunciation of the Hanja 唐手道 (pronounced Táng shǒu dào in Chinese),[2] and translates literally to "The Way of the Tang Hand."The same characters can be pronounced "karate-dō" in Japanese.

Outside of the Far East, the term "Tang Soo Do" has primarily become synonymous with the Korean martial art promoted by grandmaster Hwang Kee.

The history of the Moo Duk Kwan (from which the majority of all modern Tang Soo Do stylists can trace their lineage) can be traced to a single founder: Hwang Kee,[6] who learned Chinese martial arts while in Manchuria.”

”Between 1944 and the Liberation of Korea in 1945, the original schools or kwans of Tang Soo Do were founded in Korea by practitioners who had studied karate and had some exposure to kung-fu. Together, these original five schools and their teachers became the foundation of Tang Soo Do.

In 1964, the Korean Tae Soo Do Association was formed which, in 1965, became the Korean Tae Kwon Do Association...Actor Chuck Norris popularized Tang Soo Do in the Western world, and from it evolved the martial art Chun Kuk Do.”

Famous Veterans: Chuck Norris

“Norris joined the Air Force after high school, with the goal of training in the Security Police in preparation for a career in law enforcement. It was in the Air Force, while stationed in Korea, that Chuck was introduced to martial arts. One night on duty, Norris realized that he couldn't arrest a rowdy drunk without pulling his weapon.

He thus studied Tang Soo Do and Tae Kwan Do, both Korean martial arts, and became the first Westerner to be awarded an eighth-degree Black Belt in Tae Kwan Do. When he returned to the US, Norris served at March Air Force Base, California before being discharged in August 1962. He then worked for Northrop Aviation, but moonlighted as a karate instructor and soon was teaching full-time and running a number of martial arts schools, teaching famous celebrities such as the Osmonds, Priscilla Presley and Steve McQueen. He held the world middleweight karate champion title for six years, and was named Black Beltmagazine's "Fighter of the Year" in 1969, eventually founding 32 martial arts schools.”

“It was McQueen who encouraged Norris to go into acting. After bit roles, he captured the public's attention with his show-stopping turn as Bruce Lee's martial arts opponent in "Return of the Dragon" (1973). By the late 70s he was popular enough to headline his own movies, and starred in cult classics such as "Good Guys Wear Black," "Delta Force" and "Missing in Action." He currently stars in the popular TV series "Walker, Texas Ranger." Norris' fame grew to the point that fans began making up "Chuck Norris facts" about him (i.e., "Chuck Norris once kicked a horse in the chin. Its descendants today are known as giraffes"), and to this day new "Chuck Norris facts" are still being created, much to the good-natured Norris' amusement.”

(via Famous Veterans: Chuck Norris | Military.com)

Chinese Opera

“The name 国粹 guó cuì meaning Quintessence of the nation.

Chinese Opera is an art-form that includes many elements: music; dance; acting; mime; comedy; tragedy; acrobatics and martial arts. An aspiring opera performer has to learn to 唱念做打 chàng niàn zuò dǎ sing, talk, act and fight. Over the centuries the art form has become more refined, as in much of Chinese art, the aim is to emulate former masterpieces rather than innovate.

Operas are divided between Wenxi (civilian plays) and Wuxi (military dramas) and between dramas; comedies and farces. The story-lines come from folk tales, legends and classical literature - anything too contemporary was considered politically dangerous. It was forbidden to portray emperors or empresses of the current dynasty.”

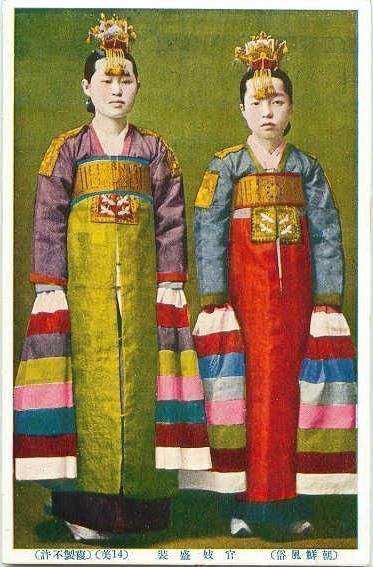

Kisaeng

“Kisaeng (Hangul: 기생; Hanja: 妓生; RR: gisaeng), sometimes called ginyeo (Hangul: 기녀; Hanja: 妓女), were enslaved women who worked to entertain others, such as yangbans and kings, during the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties. They were also courtesans, providing sexual services.[1][2] First appearing in Goryeo, kisaeng were the government's legal entertainers, required to perform various functions for the state. Many were employed at court, but they were also spread throughout the country. They were carefully trained and frequently accomplished in the fine arts, poetry, and prose, although their talents were often ignored due to their inferior social status. Aside from entertainment, these roles included medical care and needlework. Kisaengs play an important role in Korean conceptions of the traditional culture of the Joseon. Some of Korea's oldest and most popular stories, such as Chunhyangjeon, feature kisaeng as heroines.”

”As kisaeng were skilled workers from the beginning, the government took an early interest in ensuring correct education. This first emerged with the establishment of gyobang, training institutes for palace kisaeng during the Goryeo period. During the Joseon period, this became further codified. Instruction focused on music and dance.

In the three-tiered system of later Joseon, more specialized training schools were established for kisaeng of the first tier. The course of study lasted three years and covered poetry, dance, music, and art.[20] The most advanced such school was located in Pyongyang. This system continued well into the Japanese colonial period, during which time the schools training kisaeng were known as gwonbeon (Hangul: 권번).”

“Most kisaeng had a gibu, or "kisaeng husband", who provided protection and economic support, such as buying them valuable things or granting them social status in return for entertainment.[27] Most gibu were former soldiers, government enforcers, or servants of the royal household.[28] At times, there was friction between would-be customers and possessive gibu, although the gibu was not the kisaeng's husband and had no legal claim to her.[29] The role of the gibu changed over time; at first, many kisaeng in government service had no such patron.[30] However, by the late Joseon dynasty, the gibu system was more or less universal.”[31]

Geisha

“Geisha (芸者) geiko (芸子), or geigi (芸妓) are Japanese women who entertain through performing the ancient traditions of art, dance and singing, and are distinctively characterized by traditional costumes and makeup.Contrary to popular belief, Geisha are not the Eastern equivalent of a prostitute; a misconception originating in the West due to interactions with Oiran Japanese courtesans, whose traditional attire is similar to that of geisha.

The word geisha consists of two kanji, 芸 (Gei) meaning "art" and 者 (Sha) meaning "person" or "doer". The most literal translation of geisha into English would be "artist", "performing artist", or "artisan". Another name for geisha is Geiko (芸妓), which translates specifically as "Woman of Art".

In the early stages of Japanese history, there were female entertainers: Saburuko (serving girls) were mostly wandering girls whose families were displaced from struggles in the late 600s. Some of these saburuko girls sold sexual services, while others with a better education made a living by entertaining at high-class social gatherings. After the imperial court moved the capital to Heian-kyō (Kyoto) in 794 the conditions that would form geisha culture began to emerge, as it became the home of a beauty-obsessed elite.”[6]

“Traditional Japan embraced sexual delights (it is not a Shinto taboo) and men were not constrained to be faithful to their wives.[7] The ideal wife was a modest mother and manager of the home; by Confucian custom love had secondary importance. For sexual enjoyment and romantic attachment, men did not go to their wives, but to courtesans. Walled-in pleasure quarters known as yūkaku (遊廓、遊郭) were built in the 16th century,[8] and in 1617 the shogunate designated "pleasure quarters", outside of which prostitution would be illegal,[9] and within which yūjo ("play women") would be classified and licensed. The highest yūjo class was the geisha's predecessor, called tayuu, a combination of actress and prostitute, originally playing on stages set in the dry Kamo riverbed in Kyoto. They performed erotic dances and skits, and this new art was dubbed kabuku, meaning "to be wild and outrageous". The dances were called "kabuki", and this was the beginning of kabuki theater.”[9]

“These pleasure quarters quickly became glamorous entertainment centers, offering more than sex. The highly accomplished courtesans of these districts entertained their clients by dancing, singing, and playing music. Some were renowned poets and calligraphers. Gradually, they all became specialized and the new profession, purely of entertainment, arose. It was near the turn of the eighteenth century that the first entertainers of the pleasure quarters, called geisha, appeared. The first geishas were men, entertaining customers waiting to see the most popular and gifted courtesans (oiran).[9]

The first woman known to have called herself geisha was a Fukagawa prostitute, in about 1750.[13] She was a skilled singer and shamisen player named Kikuya who was an immediate success, making female geisha extremely popular in 1750s Fukagawa.[14] As they became more widespread throughout the 1760s and 1770s, many began working only as entertainers (rather than prostitutes), often in the same establishments as male geisha.”[15]

“By 1800, being a geisha was considered a female occupation (though there are still a handful of male geisha working today). Eventually, the gaudy Oiran began to fall out of fashion, becoming less popular than the chic ("iki") and modern geisha.[9] By the 1830s, the evolving geisha style was emulated by fashionable women throughout society.[16] There were many different classifications and ranks of geisha. Some women would have sex with their male customers, whereas others would entertain strictly with their art forms.[17]Prostitution in Japan was legal up until 1908, so it was practised throughout Japan.”

“In 1944, the geisha world, including the teahouses, bars and geisha houses, was forced to close, and all employees were put to work in factories. About a year later, they were allowed to reopen. The geisha name also lost some status during this time because prostitutes began referring to themselves as "geisha girls" to American military men.”[18]

”During the period of the Allied occupation of Japan, local women called "Geisha girls" worked as prostitutes. They almost exclusively serviced American GIs stationed in the country, who actually referred to them as "Geesha girls" (a mispronunciation).[73][74] These women dressed in kimono and imitated the look of geisha. Many Americans unfamiliar with the Japanese culture could not tell the difference between legitimate geisha and these costumed performers.[73] Shortly after their arrival in 1945, some occupying American GIs are said to have congregated in Ginza and shouted, "We want geesha girls!"[75]

Kabuki

“Kabuki (歌舞伎) is a classical Japanese dance-drama. Kabuki theatre is known for the stylization of its drama and for the elaborate make-upworn by some of its performers.The individual kanji, from left to right, mean sing (歌), dance (舞), and skill (伎). Kabuki is therefore sometimes translated as "the art of singing and dancing". These are, however, ateji characters which do not reflect actual etymology. The kanji of 'skill' generally refers to a performer in kabuki theatre. Since the word kabuki is believed to derive from the verb kabuku, meaning "to lean" or "to be out of the ordinary", kabuki can be interpreted as "avant-garde" or "bizarre" theatre.[1] The expression kabukimono (歌舞伎者) referred originally to those who were bizarrely dressed. It is often translated into English as "strange things" or "the crazy ones", and referred to the style of dress worn by gangs of samurai.”

“Wah Kee (华记) is a secret society based in Malaysia and Singapore since the nineteenth century.”

“A Triad is one of many branches of Chinese transnational organized crime syndicates based in China, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan and in countries with significant Chinese populations, such as the United States...

The Hong Kong triad is distinct from mainland Chinese criminal organizations.[2] In ancient China, the triad was one of three major secret societies.[3] It established branches in Macau, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Chinese communities overseas.[4] After the establishment of the People's Republic of China, all secret societies were destroyed in mainland China in a series of campaigns organized by Mao Zedong.”

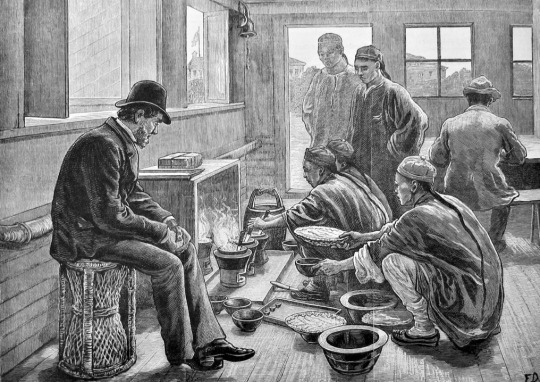

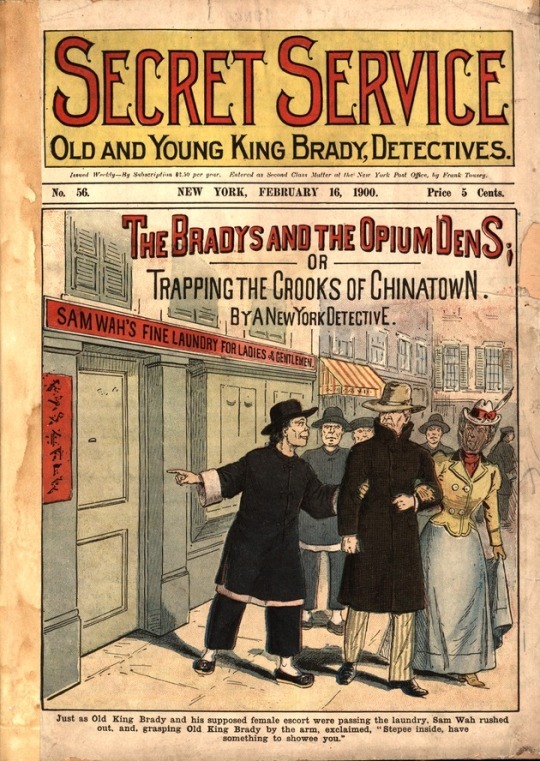

OPIUM IN THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST - 1850′s-1930′s

“Opium use among Chinese immigrants was very widespread, economically important, and -- until 1908-9 -- perfectly legal in most parts of the United States and Canada. The smugglers of opium, most of whom were European-Americans, were criminals, though tolerated and even respected in the Pacific Northwest. Smokers of opium, the majority of whom in those days were Chinese, may have been addicts but were neither criminals nor outcasts.”

Refining and Packaging Opium for Sale

“Even more prestigious were Indian opiums refined in Hong Kong, where the water and master refiners were thought to be the best in the world. This refining process does concern us, because the end result, opium "boiled" or "cooked" and packaged by a small number of Hong Kong firms, had a central influence on the economies and lifestyles of many North American Chinese in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.”

Victoria: The Largest Opium Making Center Outside Asia

“Opium refining was not confined to eastern Asia. Among the places where it was done on a large scale (but reputedly with less concern for quality) were Victoria, Vancouver, and New Westminster in British Columbia, ideally located for wholesaling (or smuggling) their products to the United States.

Opium refining seems to have gotten its real start in Canada after 1880, when a new U.S. law restricted opium refining to American citizens (Culin 1891: 499). This caused would-be Chinese refiners, none of whom by law could become U.S. citizens, to move across the border to Victoria, which then held the largest Chinese community in Canada.”

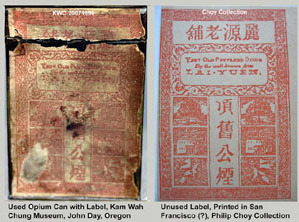

Opium Brand Names

“None except Sing Wo Chan, a branch of Macao’s immensely wealthy Sing Wo Co., seem to have specialized in opium alone. The rest had multiple lines of business. Besides opium, they were also importers and sellers of textiles, teas, groceries, and other Chinese goods, and some were labor contractors as well...None are known to have stayed in the opium business after 1908.

The names and stamped seals of Hong Kong opium producers were among the first internationally recognized brand names in the history of Asia. From the 1870s onward they were recognized in North America as well...the most favored brands of opium, Fook Lung and Lai Yuen, along with the less popular Ping Kee brand, were produced by the Yen Wo 仁和 syndicate of merchants from Dongguan, a Cantonese-speaking district southeast of Canton.”

Opium cans or "tins"

“The size of opium cans was standardized. Each held exactly 5 Chinese ounces (= liang or taels) of refined opium, about 6 1/2 ounces avoirdupois but usually calculated as a half-pound by American newspapers and the Customs Service. In the United States in 1891, the wholesale price ranged from $6.80 (for Victoria opium) to $9.00 (for the best Hong Kong opium.”

**Counterfeiting Hong Kong Opium **

“In 1882, a fascinating legal case got under way in San Francisco. The defendant was the U. S. government, which had seized 3,880 5-tael cans of opium, all bearing either “Lai Yuen” or “Fook Loong” labels, from a local man named Kennedy. He claimed that he had been shipping the opium, perfectly legally, to Hawaii, when it was seized. Maintaining that he had not broken any law, he wanted his opium--$25,000 worth--back.

Kennedy had ordered the opium, 4000 taels (2000 pounds) in all, from Choy Suey and Choy Lum, owners of Tai Hung & Co. at 1014 Dupont [Grant] Street in San Francisco. They in turn had purchased the opium, already refined, from firms named Hop Kee and Tuck Kee & Co., also in San Francisco. Until 1880, it was testified,Hop Kee had operated a “manufactory” of prepared (refined) opium in Newark, New Jersey. At Kennedy’s instructions, the Choys repackaged the Hop Kee/Tuck Kee opium to look like the Lai Yuen and Fook Long brands.

For the moment, it is enough to say that almost all of the activities described above were legal, in American if not Hawaiian law, that the witnesses, Chinese and European, testified freely, and that the only person involved who was in legal trouble was Kennedy. And even he was in no danger of prison: the issue at hand was simply whether Customs officials could keep the opium or whether they would have to give it back.”

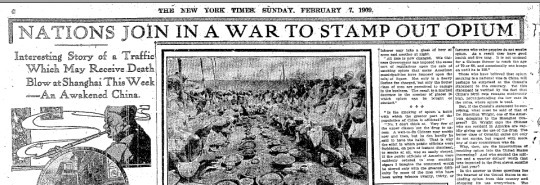

Turning Point: the 1909 Shanghai Conference

“The international conference held in Shanghai in February 1909 was heralded as (and may have really been) the single most important event in the history of effforts to ban the international trade in opium. Held in Shanghai to acknowledge China's spectacularly successful, if short-lived, efforts to suppress narcotics use, especially the smoking of opium, the conference brought all of the major national players to the same table and, in the glare of unprecedented international publicity, forced them to commit to eliminating the opium trade and opium use.

One more or less direct effect was to convince the United States Congress that the time had come to enact a serious anti-opium law. The one passed that year became the foundation of all subsequent anti-narcotics efforts in this country and helped to convince other countries that similar laws were imperative.”

Curing Addicts and Outlawing the Opium Trade: The Missionary Connection

“In the English-speaking world, much of the pressure to ban opium and to cure addicts, sometimes through incarceration or worse, came from missionaries working in China and among overseas Chinese. The most radical anti-opium missionaries tended to be British, American, or Canadian Protestants as well as their Chinese converts, some of whom...also became religious professionals...For now it is enough to note that there was a strong religious element in anti-opium campaigns, that intolerance and righteous exaggeration were the inevitable result, and that in spite of this, Chinese everywhere owe a debt to Christian churches of the late 19th-early 20th centuries for supporting Chinese efforts to outlaw opium use and for campaigning successfully in the West to end the legal international trade in opium.”

#taipingrevolt#boxerrebellion#mandateofheaven#8banners#tangsoodo#martialarts#kungfu#shaolintemple#josshouse#chewkeejossstore#courttranslator#puplfiction#journalism#tonggangwars#wahkeelaundry#opiumden#dynasticcycle#rise&fallofcommunism

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Immigration

As someone who came to the United States to pursue my dream of becoming my lawyer, I understand that obtaining citizenship and figuring out what you need can be very difficult. That's why I offer specialized immigration services, with court translation and interpreting from English to Vietnamese and vice-versa to help clients secure citizenship. I also handle deportation cases so that families can be reunited. For more information about my immigration services, please get in touch with me at Certified Vietnamese Court Interpreter_Kristie Thanh Nguyen today!

https://fountainvalleycourttranslator.com

#CourtTranslation#CertifiedVietnameseTranslator#VietnameseTranslator#ImmigrationServices#ProbateRealEstate#Bankruptcy#CourtInterpreting#CertifiedVietnameseInterpreter#CertifiedVietnameseCourtInterpreter#VietnameseInterpreter#LegalServices#DeportationCases#ProbateListingAgent#RealEstateListings#DivorceCases

0 notes

Photo

Real Estate

As a certified probate real estate specialist and licensed real estate agent, I can help you deal with any difficulties that may arise when trying to transfer property via probate. I can also help with marketing your property, conducting comparative analysis, creating real estate listings, and completing the necessary closing documents. Understand the ins and outs of the housing market and close any affairs that need wrapping up with professional assistance from a qualified probate listing agent. To learn more about my services, please contact me at Certified Vietnamese Court Interpreter_Kristie Thanh Nguyen today!

https://fountainvalleycourttranslator.com

#CourtTranslation#CertifiedVietnameseTranslator#VietnameseTranslator#ImmigrationServices#ProbateRealEstate#Bankruptcy#CourtInterpreting#CertifiedVietnameseInterpreter#CertifiedVietnameseCourtInterpreter#VietnameseInterpreter#LegalServices#DeportationCases#ProbateListingAgent#RealEstateListings#DivorceCases

0 notes

Photo

Legal Services

When it comes to navigating the legal system, you can count on me to help you win your case. I am well-versed in many areas of the law and can assist with anything from traffic tickets to divorce cases. My services also include navigating wills and trusts, name changes, domestic violence cases, bankruptcy, and interpretation and translation from English to Vietnamese and vice-versa. I will provide you with sound legal counsel so that you can present a solid case, so for more information about how you can take advantage of my legal services, please contact me at Certified Vietnamese Court Interpreter_Kristie Thanh Nguyen today!

https://fountainvalleycourttranslator.com

#CourtTranslation#CertifiedVietnameseTranslator#VietnameseTranslator#ImmigrationServices#ProbateRealEstate#Bankruptcy#CourtInterpreting#CertifiedVietnameseInterpreter#CertifiedVietnameseCourtInterpreter#VietnameseInterpreter#LegalServices#DeportationCases#ProbateListingAgent#RealEstateListings#DivorceCases

0 notes