#Clifford Herschel Moore

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

The Eruption of Mt. Vesuvius

The Eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 CE remains one of the deadliest natural disasters in recorded history. Not only did the volcano destroy the economically powerful city of Pompeii, but Herculaneum, Oplontis, Stabiae were also buried and thus lost to the Roman Empire. The number of victims is unknown, but given the size of the four cities, estimates have reached over 18,000 individuals.

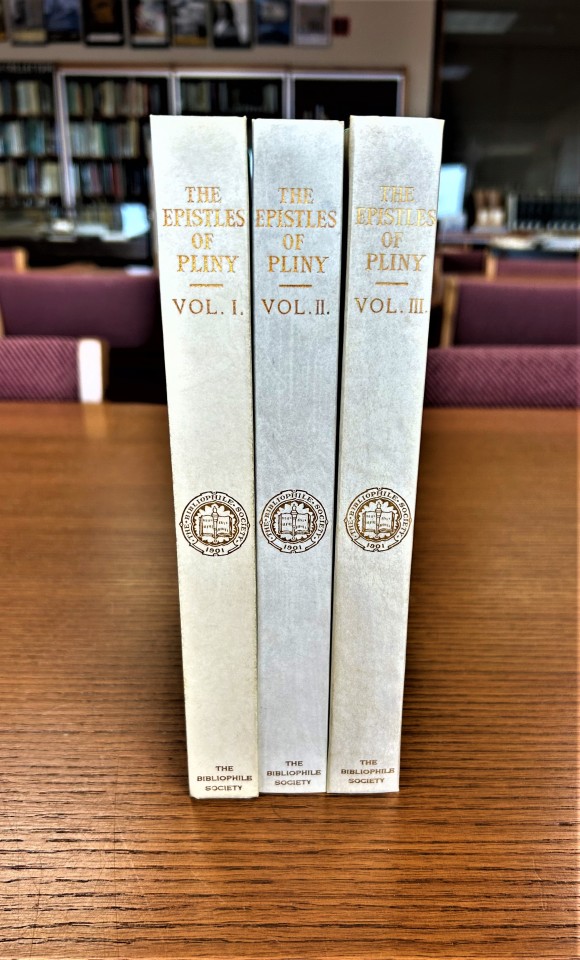

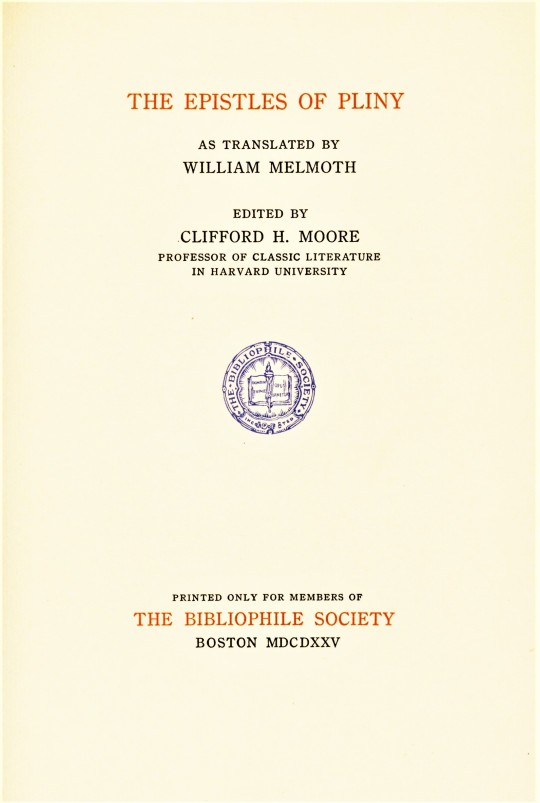

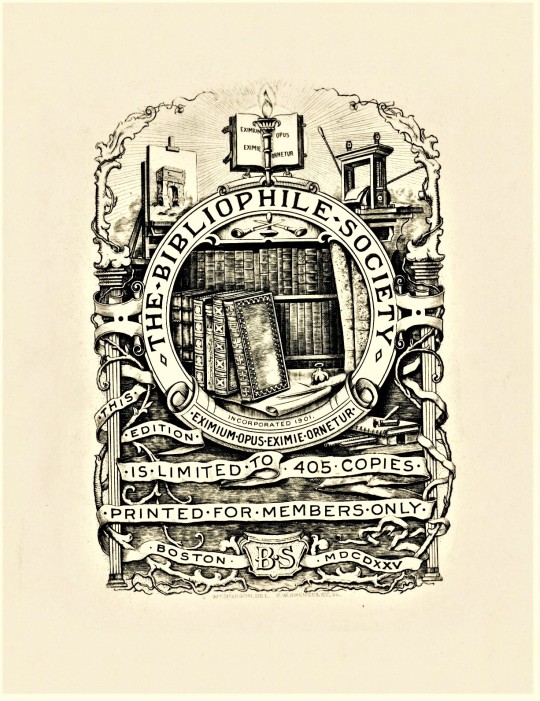

Today only one first-hand account of this horrific event survives in two letters from Pliny the Younger to the Roman historian Tacitus. They are preserved as letters 6.16 and 6.20 in the collected Epistles of Pliny. Among our holdings of the works of Pliny is this 3-volume set of the Epistles with William Melmoth’s 18th-century translation edited by Clifford Herschel Moore, and printed by the Harvard University Press in an edition of 405 copies for members of The Bibliophile Society, Boston, in 1925.

While the term ‘volcanic eruption’ evokes scenes of lava and fire, the reality is much more frightening. Curiously, there is no word for volcano in the Latin language. While ancient Romans were aware of the destructive power of volcanoes, there’s some debate about whether they were aware that Vesuvius was a volcano before its eruption. Signs of the eruption began back in 62CE with a great earthquake that caused much of the city to collapse. Smaller earthquakes continued over the next 15 years until one was accompanied by the rise of a column of smoke from Mt. Vesuvius in October 79 CE.

The hot gases that made up the column of smoke began to cool, darkening the sky, and not long after a rain of pumice began to fall, and after 15 hours ceilings began to collapse. Nevertheless, many residents chose to take shelter rather than flee. At 4am the first 500C pyroclastic surge barred down the volcano, burying Herculaneum. Six more of these surges occurred before the end of the eruption, destroying Pompeii, Oplontis, and Stabiae.

The 17-year old Pliny was in the port town of Misenum across the Bay of Naples from the volcano at the time. Pliny’s uncle, Pliny the Elder, commander of the Roman fleet at Misenum, launched a rescue mission and went himself to the rescue of a personal friend. The elder Pliny did not survive the attempt. In Pliny the Younger’s first letter to Tacitus, he relates what he could discover from witnesses of his uncle's experiences. In a second letter, he details his own observations after the departure of his uncle.

Mt. Vesuvius is still active and according to volcanologists, erupts about every 2000 years, which would be right about now. Who will be our next Pliny the Younger?

Our copy of The Epistles of Pliny is another gift from our friend and benefactor Jerry Buff.

View more of my Classics posts.

– LauraJean, Special Collections Undergraduate Classics Intern

#Classics#classical history#Roman History#Mt. Vesuvius#Eruption of Mt. Vesuvius#Pliny the Younger#Epistles of Pliny the Younger#Pliny the Elder#Tacitus#William Melmoth#Clifford Herschel Moore#Harvard University Press#The Bibliophile Society#volcanic eruptions#Pompeii#herculaneum#Oplontis#Stabiae#Jerry Buff#LauraJean

96 notes

·

View notes

Link

AuthorMoore, Clifford Herschel, 1866-1931 LoC No.18019585 TitlePagan Ideas of Immortality During the Early Roman Empire LanguageEnglish LoC ClassBL: Philosophy, Psychology, Religion: Religion: General, Miscellaneous and Atheism SubjectRome -- Religion SubjectImmortality CategoryText EBook-No.53829 Release DateDec 29, 2016 Copyright StatusPublic domain in the USA.

The most important single religious document from the Augustan Age is the sixth book of Virgil’s Aeneid; for although the Aeneid was written primarily to glorify Roman imperial aims, the sixth book gives full expression to many philosophic and popular ideas of the other world and of the future life, which were current among both Greeks and Romans.[1] It therefore makes a fitting point of departure{3} for our considerations. In this book, as you will remember, the poet’s hero, having reached Italian soil at last, is led down to the lower world by the Cumaean Sybil. This descent to Hades belongs historically to that long series of apocalyptic writings which begins with the eleventh book of the Odyssey and closes with Dante’s Divine Comedy. Warde Fowler deserves credit for clearly pointing out that this visit of Aeneas to the world below is the final ordeal for him, a mystic initiation, in which he receives “enlightenment for the toil, peril, and triumph that await him in the accomplishment of his divine mission.” When the Trojan hero has learned from his father’s shade the mysteries of life and death, and has been taught the magnitude of the work which lies before him, and the great things that are to be, he casts off the timidity which he has hitherto shown and, strengthened{4} by his experiences, advances to the perfect accomplishment of his task.[2] [2-4]

1 note

·

View note

Link

AuthorMoore, Clifford Herschel, 1866-1931 TitleThe Religious Thought of the Greeks LanguageEnglish CategoryText EBook-No.61395 Release DateFeb 13, 2020 Copyright StatusPublic domain in the USA.

In their conquests of eastern lands Roman soldiers came directly into contact with Asiatic, Syrian, and Egyptian forms of religion, so that on their return to the West they brought with them some knowledge of eastern gods. But the influence of oriental cults had begun before Rome [260]entered on her military conquests; for a long time she had had mercantile and diplomatic relations with Asia Minor and Egypt. Trade indeed was one of the great channels through which gods no less than goods moved from the East to the West. The Greeks of western Asia Minor, of Delos, of southern Italy and Sicily were the middlemen who assisted in these transfers. Furthermore, beginning with the second pre-christian century, enormous numbers of slaves were brought from Asia Minor and the neighboring lands to Italy and the West. These slaves were of every degree from the most ignorant to the highly cultivated, but whatever their class they brought with them their own religions, which they practised in their captivity and thus made known to their masters. At a later period, under the Empire, auxiliary troops, enlisted in the eastern provinces, were stationed at many points in the West. The remains of shrines and hundreds of inscriptions found along the Danube and the Rhine, in remotest Britain, in Spain and Portugal, as well as in France and other lands, show that these auxiliary troops did much to introduce oriental gods to the areas in which they served. [260]

0 notes