#Clan del Golfo

Text

El clan del golfo utiliza a los migrantes que pasan por el Darién como mulas para trasladar droga

La Policía colombiana y organismos internacionales han detectado cómo operan los criminales en esa zona selvática

PorYalilé Loaiza

Los migrantes deben pagar cientos de dólares para cruzar por la selva. (AP Foto/Arnulfo Franco)

La ecuatoriana es la segunda nacionalidad de los migrantes que más cruzan por la selva del Darién en su trayecto hacia los Estados Unidos. Los riesgos de ese tramo…

View On WordPress

#Autor Yalilé Loaiza#Clan del Golfo#Colombia#Infobae#Migrantes#Mulas#Selva del Darién#Traslado de drogas

0 notes

Text

ELN guerrilla against Clan del Golfo narco-paramilitaries, in the Department of Nariño, Pacific coast

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Autoridades de Colombia capturaron al “rey” de los narcosubmarinos, pero estos siguen proliferando.

Las autoridades de Colombia capturaron al “rey” de los narcosubmarinos del país, un hombre cuyos servicios, según los fiscales, han sido empleados por poderosos grupos criminales de varios países, desde Colombia hasta México.

Óscar Moreno Ricardo, arrestado en Medellín a principios de enero, es pedido en extradición por las autoridades estadounidenses por cargos relacionados con narcotráfico, según fiscales colombianos que alegan que él era el principal responsable de coordinar la fabricación y el despacho de semisumergibles cargados de cocaína desde la costa Pacífica colombiana.

Die kolumbianischen Behörden haben den „König“ der Drogen-U-Boote gefangen genommen, aber sie vermehren sich weiter.

Die kolumbianischen Behörden haben den „König“ der Drogen-U-Boote des Landes gefangen genommen, einen Mann, dessen Dienste laut Staatsanwälten von mächtigen kriminellen Gruppen in mehreren Ländern, von Kolumbien bis Mexiko, in Anspruch genommen wurden.

Óscar Moreno Ricardo, der Anfang Januar in Medellín festgenommen wurde, wird von den US-Behörden wegen Vorwürfen im Zusammenhang mit Drogenhandel zur Auslieferung aufgefordert, so die kolumbianische Staatsanwaltschaft, die ihm vorwirft, er sei hauptsächlich für die Koordinierung der Herstellung und des Versands von mit Kokain beladenen Halbtauchbooten verantwortlich gewesen der kolumbianischen Pazifikküste.

Según la Fiscalía General de la Nación, la participación de Moreno Ricardo en el tráfico de drogas se remonta a 2005, cuando se desempeñaba como piloto de lanchas rápidas. Los fiscales dicen que, poco después, ya coordinaba cargamentos para carteles mexicanos y grupos armados colombianos. Hace unos cinco años, Moreno Ricardo supuestamente comenzó a fabricar semisumergibles que transportaban hasta cinco toneladas de cocaína y eran enviados a Centroamérica, lo que, según los fiscales, llevó a que recibiera el apodo del “rey de los narcosubmarinos”. En el mundo del hampa, al parecer era conocido como “Cachano” y “El Viejo”.

Los fiscales sostienen que Moreno Ricardo tenía vínculos con varios grupos criminales, incluido el clan narcotraficante colombiano Los Urabeños, también conocidos como Clan del Golfo; la organización guerrillera colombiana Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN), y el Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación (CJNG), de México.

La hija de Moreno Ricardo le dijo al medio colombiano Bluradio que su padre fue arrestado injustamente, pues sostiene que él tiene el mismo apodo del acusado, “Cachano”, y que en realidad es un ganadero de Acandí, municipio del departamento de Chocó, al occidente colombiano. El hombre al que están buscando, asegura ella, vive y opera más hacia el sur, en el municipio de Tumaco, departamento de Nariño.

Nach Angaben der Generalstaatsanwaltschaft geht Moreno Ricardos Beteiligung am Drogenhandel auf das Jahr 2005 zurück, als er als Schnellbootpilot arbeitete. Staatsanwälte sagen, dass er kurz darauf Lieferungen für mexikanische Kartelle und kolumbianische bewaffnete Gruppen koordinierte. Vor etwa fünf Jahren begann Moreno Ricardo angeblich mit der Herstellung von Halbtauchbooten, die bis zu fünf Tonnen Kokain transportierten und nach Mittelamerika verschifft wurden, was ihm nach Angaben der Staatsanwaltschaft den Spitznamen „König der Drogen-U-Boote“ einbrachte. In der Unterwelt war er offenbar als „Cachano“ und „El Viejo“ bekannt.

Die Staatsanwälte behaupten, dass Moreno Ricardo Verbindungen zu mehreren kriminellen Gruppen hatte, darunter dem kolumbianischen Drogenhändler-Clan Los Urabeños, auch bekannt als Clan del Golfo; die kolumbianische Guerillaorganisation National Liberation Army (ELN) und das Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG) aus Mexiko.

Die Tochter von Moreno Ricardo teilte den kolumbianischen Medien Bluradio mit, dass ihr Vater zu Unrecht verhaftet worden sei, da sie behauptet, er habe denselben Spitznamen wie der Angeklagte, „Cachano“, und sei in Wirklichkeit ein Viehzüchter aus Acandí, einer Gemeinde im Departement Chocó. al Kolumbianischer Westen. Der gesuchte Mann lebe und arbeite weiter südlich, in der Gemeinde Tumaco im Departement Nariño, sagt sie.

Análisis

Es probable que las autoridades hayan «hundido» al presunto capo de la droga, pero los semisumergibles para transportar cocaína, que se usan desde hace más de tres décadas, continúa aumentando a medida que se extiende el conocimiento necesario para construir dichas naves.

Aunque para fabricar narcosubmarinos se requiere hacer grandes inversiones, estas ofrecen grandes ventajas para el contrabando marítimo de drogas, dado lo difícil que es detectarlos e interceptarlos. En Colombia, donde se ha perfeccionado el diseño y la fabricación de narcosubmarinos, las autoridades incautaron 31 embarcaciones en 2021, un aumento con respecto a las 23 de 2019.

Los traficantes de otras partes de la región también han empleado narcosubmarinos, y se han encontrado embarcaciones en aguas de Surinam, Brasil, Venezuela y Guyana. En 2019, el primer narcosubmarino interceptado en Europa fue encontrado frente a la costa de Galicia, España. La nave transportaba tres toneladas de cocaína desde Colombia. En 2021, las autoridades allanaron una bodega en la provincia costera de Málaga, España, donde se estaba construyendo un narcosubmarino.

La reciente proliferación de estas naves se debe en parte a que los delincuentes subcontratan sus servicios a una amplia gama de grupos traficantes. Este modelo de subcontratación les evita a estos grupos las labores de diseño, fabricación y logística necesarias para elaborar dichas naves.

Die jüngste Verbreitung dieser Schiffe ist teilweise darauf zurückzuführen, dass Kriminelle ihre Dienste an eine Vielzahl von Schleppergruppen auslagern. Dieses Unterauftragsmodell erspart diesen Gruppen die Design-, Fertigungs- und Logistikaufgaben, die für die Entwicklung dieser Lagerhäuser erforderlich sind.

Los criminales colombianos están liderando el negocio de los “narcosubmarinos de alquiler”. En diciembre de 2020, autoridades estadounidenses y colombianas desmantelaron una organización que se especializaba en la fabricación y adaptación de semisumergibles para el tráfico de cocaína. Entre sus clientes se encontraban el ELN y diversos carteles mexicanos.

En 2018, las autoridades de Surinam arrestaron a varios hombres colombianos que habían sido empleados para construir un submarino que sería utilizado para exportar cocaína de Surinam a Europa. Entre los acusados se encontraba el primo de Rodrigo Pineda, un vendedor de maquinaria pesada acusado de ser uno de los mayores fabricantes de semisumergibles para narcotraficantes en el departamento de Nariño, en la costa Pacífica colombiana.

Kolumbianische Kriminelle sind führend im „Drogen-U-Boot-Verleih“-Geschäft. Im Dezember 2020 lösten US-amerikanische und kolumbianische Behörden eine Organisation auf, die sich auf die Herstellung und Anpassung von Halbtauchbooten für den Kokainhandel spezialisiert hatte. Zu seinen Kunden gehörten die ELN und verschiedene mexikanische Kartelle.

Im Jahr 2018 verhafteten die Behörden von Surinam mehrere kolumbianische Männer, die mit dem Bau eines U-Bootes beschäftigt waren, das für den Kokainexport von Suriname nach Europa verwendet werden sollte. Unter den Angeklagten war der Cousin von Rodrigo Pineda, einem Schwermaschinenverkäufer, der beschuldigt wird, einer der größten Hersteller von Halbtauchbooten für Drogenhändler im Departement Nariño an der kolumbianischen Pazifikküste zu sein.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Using the U.S. military in Mexico to deal with the fentanyl crisis in the United States is the hot new policy solution for lots of U.S. politicians. The top three Republican presidential candidates have endorsed using the U.S. military to fight Mexican cartels. Similarly, Republican Rep. Dan Crenshaw, the newly appointed chair of a congressional task force for countering Mexican cartels, announced recently that “Colombia is the model” for what Washington needs to do in Mexico.

Crenshaw is the author of a bill in Congress authorizing the use of military force against Mexican cartels or any actor “carrying out other related activities that cause regional destabilization in the Western Hemisphere.” He argues that the “American partnership” with Colombia helped make the country safer today than it was 25 years ago and that this provides a model for dealing with Mexican cartels:

“We need to somehow figure out diplomatically how to make this Mexico’s idea. That they’re asking for our military support, such as close air support, such as an AC-130 gunship overhead while they’re prosecuting a target and surrounded by sicarios. … If I was in that situation as a Navy SEAL, we would just call in close air support, all those guys would be gone, and we’d move along our merry way.”

This is bad analysis on a number of levels: bad history, bad economics, and bad political science. Since Crenshaw has volunteered himself as an expert on Colombia—he went to high school there—and its lessons for fighting the war on drugs with the U.S. military, we can start with his proposals.

In an Instagram post, Crenshaw stated, “Anyone who has watched Narcos knows that the Colombia of 30 years ago looked a lot like Mexico does today.”

The problem with that theory—beyond its reliance on a Netflix series to formulate U.S. foreign policy—is twofold. To begin with, if you consider annual homicide rates, today’s Mexico looks an awful lot like today’s Colombia. In 2021, Mexico had 28 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, whereas Colombia’s rate was 27. This convergence—Mexico’s homicide rate surpassed Colombia’s for the first time in 2017—is certainly bad news for the former country, whose homicide rate was 8 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2007, one year after then-President Felipe Calderón deployed Mexican Army troops to fight the drug cartels. Nonetheless, despite seeing its homicide rate more than triple in less than two decades, Mexico is still nowhere near Colombia’s levels of violence during the Narcos era of the late 1980s and early 1990s, when the country reached the alarming rate of 85 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants. Comparing Mexico’s violence in 2023 to that of Colombia in 1993 borders on the preposterous.

Crenshaw’s argument also overlooks that Colombia today is slipping back to the 1990s, when the country, under siege from the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), a narco-guerrilla group, was on the verge of becoming a failed state. Although the homicide rate remains comparatively low, large swaths of the national territory are still under the control of the FARC and other illegal armed groups, which are expanding their spheres of influence. In May, the U.S. State Department issued a travel advisory to warn that three of the country’s 32 departments (the equivalent of U.S. states)—Cauca in the country’s southwest, Arauca and Norte de Santander in eastern Colombia—were high-risk areas due to widespread organized criminal activities including homicide, assault, armed robbery, extortion, and kidnapping.

According to the International Committee of the Red Cross, seven different armed conflicts are now taking place in Colombia (an increase from six in 2022). While the Colombian state battles the FARC, the National Liberation Army (ELN), and the Clan del Golfo, the latter armed group is waging its own war against the ELN. The FARC, meanwhile, is fighting two of its own splinter groups, Segunda Marquetalia and Comandos de la Frontera, the latter of which operates along extensive parts of the Venezuelan border. Finally, the FARC and the ELN, both communist narco-guerrilla groups, are facing off against each other for control over Arauca, a department that also controls key access routes into Venezuela.

Although each of the unofficial armed actors takes part in illegal mining, extortion, and other criminal activities, their main source of financing—and the main source of the conflicts among them—is the cocaine trade. The major difference between the situation now and that of the 1990s is that no single group enjoys a monopoly over the drug trade while waging an all-out war against the state, as the FARC then did. Instead, a multitude of armed actors fight both the state and one another over strategic coca-growing areas and export routes.

It is true that, overall, the conflict now has a lower intensity than in the 1990s, but Crenshaw’s thesis that Colombia is a safer, more peaceful place today than it was when he lived there at the turn of the century is valid only up to a point. For the population in entire departments like Arauca, Norte de Santander, and Cauca, the security situation is no less lethal now than two or three decades ago. It is unquestionable that the change in strategy in Bogotá and the assistance from Washington helped the Colombian military in its struggle against insurgent groups. But this misses the point. From a U.S. perspective, the reason for getting involved in the first place was to stanch the flow of cocaine into the United States. As seen above, that objective was not attained. From Colombia’s perspective, the tactical victory provided a some Colombians refuge from the conflict, but the country is still afflicted by the endemic violence that plagues countries stuck in the middle of the drug war.

The last four years have also seen a resurgence of the type of violence that struck the country when the Medellín Cartel and the FARC were at the apex of their powers. In 2019, the ELN carried out a deadly terrorist attack against the National Police Academy in Bogotá, killing 21 with the detonation of a car bomb. In March, the ELN attacked a military base in Norte de Santander with explosives, leaving nine soldiers dead. The FARC, meanwhile, recently reestablished its 53rd Front in Sumapaz, a rural locality of Bogotá, thus reviving dark memories of 1999, when the terrorist group threatened the Colombian capital itself.

Given the persistence of armed groups financed with cocaine proceeds and the continuation of drug-fueled violence in Colombia, it is telling that Crenshaw, while heralding Colombia as a model for U.S. policy in Mexico, does not mention cocaine once. That was the reason the United States got involved in Colombia in the first place. In the 1980s and into the 1990s, there was an enormous increase in the flow of powder and then crack cocaine into U.S. cities. U.S. politicians concluded that the solution was to use U.S. military aid to help solve problems inside Colombia, drying up the supply of the drug at the source. As a result, under Plan Colombia and its successor counter-narcotics programs, nearly $12 billion was dedicated to helping the Colombian military eradicate coca leaf and undermine actors participating in the cocaine trade between 2000 and 2021.

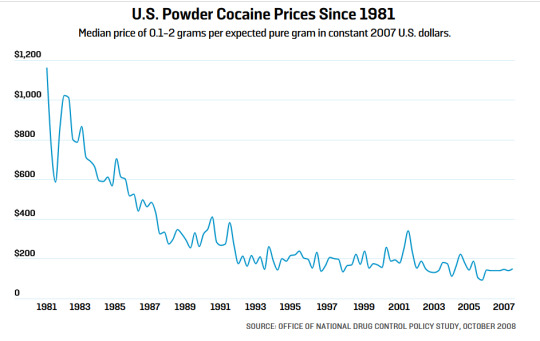

Unfortunately, as an Office of National Drug Control Policy study showed in October 2008, cocaine prices in the United States consistently declined in the 1980s, and then remained relatively flat throughout the 1990s. The idea of attacking the drug supply at the source relies on the idea that interdiction will reduce availability and drive prices up, limiting consumption and negative consequences at home. If price is not even increasing, that is proof positive that a supply-side model is not working.

The large expenditure of American taxpayer money in Colombia did nothing to halt the spread of coca crops, illicit drug production, or the continuous export of cocaine to the United States. On the contrary, coca cultivation in Colombia increased between 2000 and 2020, from roughly 136,000 planted hectares to a record 245,000. In this sense, Plan Colombia’s counter-narcotics element can be seen as an utter failure, even if its military component did help the Colombian military launch an effective offensive against the FARC in the 2000s.

That is why Crenshaw’s soliloquy on how Colombia should be a model for our policy in Mexico is so strange. The U.S. government failed to solve the cocaine problem, but Crenshaw now heralds the “Colombia model” as an unqualified success. The reason we went into Colombia in the first place, cocaine, just fell out of the story altogether. The “do something!” impulse in U.S. foreign policy is strong, but surely a proposed solution to a problem should be able to pass scrutiny better than this.

Colombia’s drug war has proved to be a Sisyphean struggle, with each victory against the dominant drug cartel leaving a power vacuum that is quickly filled by new drug cartels. The Medellín Cartel’s fall led to the rise of the Cali Cartel, whose own demise allowed the FARC and a series of paramilitary groups to take over the cocaine business.

Between 2002 and 2010, then-President Álvaro Uribe’s government successfully fought the FARC, but this was undercut by the fact that it was impossible to do away fully with the FARC’s main source of financing (cocaine). Hence, the FARC, despite heavy blows to its leadership structure, didn’t surrender fully and was able to outlast Uribe’s government. Uribe’s successor, Juan Manuel Santos, negotiated with the FARC and amnestied its leadership, yet only a part of the FARC demobilized in 2016. The rest, known locally as FARC dissidents, remained up in arms and, as mentioned, remain fully immersed in the drug trade.

As shown above, this hardly made a dent on the supply of cocaine to the United States. If anything, the fentanyl problem is even more daunting. Cocaine is much more expensive and difficult to produce than fentanyl. During Plan Colombia, U.S. and Colombian pilots sprayed more than a million acres of Colombian territory with glyphosate in an attempt to eradicate coca crops. Fentanyl is produced on a much smaller scale with comparatively tiny amounts of precursor chemicals that are easy to obtain. Fentanyl could be produced in meaningful quantities almost anywhere. Even if Mexico stopped producing any fentanyl, there is little reason to believe U.S. supply would evaporate.

And the profit margins are astounding: According to an indictment of the Sinaloa Cartel in the Southern District of New York in April, $800 of fentanyl precursor chemicals can produce up to $640,000 worth of retail value in U.S. cities. Even if greater interdiction cuts into those margins, they are large enough to absorb a lot of pressure.

As an unintended result of the drug war, Mexico has already become a heavily militarized country. As one of us has previously noted, the tendency has increased dramatically under President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who has put the army in charge of infrastructure projects, customs duties at ports and airports, gasoline and fertilizer distribution, school textbook deliveries, and the provision of hospital materials, among other mundane or strictly logistical tasks that, even in many Latin American countries, fall well outside the military sphere.

In 2019, López Obrador created the National Guard, a new branch of the armed forces with over 100,000 regulars (compared to less than 150,000 in the army proper). In recent years, influential members of the armed forces have waded into politics, thus breaking the decadeslong tradition of an apolitical military. If anything, the United States should refrain from abetting any further militarization of Mexico. Plans to further involve the U.S. military against Mexico’s drug cartels, however, would likely add fuel to the fire.

A final word might bear mentioning, since Crenshaw referenced the Netflix series Narcos. The series continues after the denouement of the Medellín and Cali cartels in Colombia. There is a second series, set in Mexico. The first episode sets the scene quite clearly, with DEA agent Walt Breslin growling over a spliced cut of grim drug war clips:

“I’m going to tell you a story, but I’ll be honest: It doesn’t have a happy ending. In fact, it doesn’t have an ending at all. … It’s about … a war. … A drug war. The kind that’s easy to forget is happening, until you realize that in the last 30 years in Mexico, it’s killed half a million people—and counting. … I can’t tell you how the drug war ends. Man, I can’t even tell you if it ends.”

Crenshaw, and the leading Republican candidates for president, want you to believe that they have a plan for how the drug war in Mexico ends.

Ask yourself: Should you believe them?

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Asentamientos de Mapa- Reclusorio de los Malditos N°1

La maldición hereditaria con la que lidian todos los miembros de los Heraldos de Dragones es una carga que ha durado miles de años en su linaje. Si bien cada clan posee formas de aliviar las consecuencias de la sangre maldita no existe una cura para esta, y por lo tanto antes de que la maldición se salga de control y deforma en cuerpo y alma a los individuos, existe la tradición de expulsar a los miembros del seno del clan.

Gracias a esta práctica no es extraño encontrar campamentos de enfermos por la maldición dracónica dispersos por gran cantidad de sitios, intentado alejarse lo más posible, muchos de estos malditos han encontrado consuelo a la par de otros semejantes, mientras que otros han asumido su fatídico destino y se preparan para el día que las violentas mutaciones afloren en su cuerpo y los consuman.

Los Reclusorios de los Malditos son Asentamientos de Mapa en los cuales los enfermos exiliados de los distintos clanes de Heraldos de Dragones termina, allí los enfermos viven en aldeas cerradas a los extranjeros, aunque es común que muchos de estos partan en búsqueda de la sabiduría para controlar la maldición, volviendo como Sabios y Ermitaños.

Podemos encontrar los Reclusorios de los Malditos en los siguientes mapas: Marismas lavamar, Marismas del Dragón, Costa estéril, Costa de las Perlas y el Golfo de Mehdijeh, siendo común encontrar estos reclusorios en las tierras más alejadas de los grandes centros urbanos de los clanes principales.

#concept art#ulk#worldbuilding#fantasy art#lore#fantasy#asentamientos de mapa#reclusorio de los malditos

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

El Clan del Golfo: Cómo el Crimen Organizado Infiltró la Reconstrucción de Providencia bajo la Mirada del Gobierno"

El Clan del Golfo se ha involucrado en diversas actividades ilícitas a lo largo de los años, y su presencia en varias regiones de Colombia les ha permitido diversificar sus fuentes de ingresos, incluida la explotación ilegal de recursos naturales. En el caso de la madera utilizada para la reconstrucción de Providencia tras el huracán Iota, hay reportes de que esta organización criminal vio una…

0 notes

Video

youtube

La historia de 'Otoniel', líder del Clan del Golfo

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

El ELN levanta el “paro armado” en una zona del departamento colombiano del Chocó

El ELN anunció esta medida el pasado domingo debido a la ofensiva del Clan del Golfo, la principal banda criminal de Colombia, y afectaba a los municipios de Istmina, Medio Baudó, Sipí, Nóvita y Medio San Juan, que están en las cuencas de los ríos San Juan, Sipí y Cajón, además de la carretera que conecta a Nóvita con Torrá.

“Damos por finalizado el paro armado a partir de las 6:00 am del día 19…

0 notes

Text

Colombia autoriza instalar espacio de conversación con banda criminal Clan del Golfo

Bogotá, (VOA),- El gobierno de Colombia autorizó la instalación de un “espacio de conversación sociojurídico” con el Clan del Golfo, la mayor banda criminal del país, para verificar su voluntad de transitar al Estado de Derecho y fijar los términos de sometimiento a la justicia, reveló el lunes una resolución gubernamental.

La decisión de instalar el espacio de conversación hace parte de los…

0 notes

Text

Fiscalía General de la Nación

Fueron ocupados con fines de extinción de dominio bienes avaluados en más de 16.000 millones de pesos, ubicados en cuatro departamentos del país.

El trabajo investigativo desplegado por la Fiscalía General de la Nación contra las diferentes estructuras del ‘Clan del Golfo’, permitieron identificar 44 bienes que harían parte del patrimonio ilícito constituido por varios de los jefes armados y…

0 notes

Text

Fiscalía General de la Nación

Fueron ocupados con fines de extinción de dominio bienes avaluados en más de 16.000 millones de pesos, ubicados en cuatro departamentos del país.

El trabajo investigativo desplegado por la Fiscalía General de la Nación contra las diferentes estructuras del ‘Clan del Golfo’, permitieron identificar 44 bienes que harían parte del patrimonio ilícito constituido por varios de los jefes armados y…

0 notes

Text

Estados Unidos ofrece tres recompensas que hacen un monto de 8 millones de dólares por información que lleve a la captura de líderes del Cartel del Go...

0 notes

Text

Gracias de antemano por sus comentarios

Exjefe del Clan del Golfo podría declarase culpable en EE.UU.

La fiscalía de la corte este de Nueva York incluyó en su agenda del martes una audiencia para Rendón Herrera, exjefe del Clan del Golfo.

Nueva York, EE.UU. (VOA) - El colombiano Daniel Rendón Herrera, quien fue uno de los narcotraficantes más buscados en Colombia, podría declararse culpable de uno o más cargos que enfrenta en una corte...

Sigue leyendo: https://www.adiario.mx/mexico/exjefe-del-clan-del-golfo-podria-declarase-culpable-en-ee-uu/?feed_id=158649&_unique_id=665f89f2aa7a1

0 notes

Text

Illicit Drug Gangs in Colombia

Colombia has long been associated with drug trafficking and the violent drug cartels that have dominated the country's underworld for decades. These illicit drug gangs have had a devastating impact on Colombian society, leading to rampant violence, corruption, and instability. While the country has made significant progress in recent years in combating these criminal organisations, they continue to pose a serious threat to the security and well-being of the Colombian people.

The most infamous of these drug gangs was the Medellín Cartel, led by the notorious drug lord Pablo Escobar. The cartel was responsible for smuggling vast quantities of cocaine into the United States and Europe, amassing a fortune estimated at billions of dollars in the process. Escobar's reign of terror in the 1980s and 1990s led to countless deaths and the destruction of entire communities. The Colombian government, with the help of US authorities, eventually brought down Escobar and dismantled his cartel, but the vacuum left behind was quickly filled by other criminal organisations.

One of the most powerful drug gangs operating in Colombia today is the Clan del Golfo, also known as Los Urabeños. This paramilitary group controls large swaths of territory in the country and is heavily involved in drug trafficking, extortion, and other criminal activities. The group has been responsible for a number of high-profile attacks against civilians and security forces, leading to increased levels of violence in the regions under its control.

Another major player in the Colombian drug trade is the National Liberation Army (ELN), a Marxist guerrilla group that has been involved in drug trafficking to fund its insurgency against the government. The ELN has been responsible for numerous kidnappings, bombings, and other acts of violence, further destabilising the already fragile security situation in Colombia.

Despite ongoing efforts by the Colombian government to combat these criminal organisations, the illicit drug trade continues to thrive in the country, fuelled by high demand in foreign markets and the attractive profits to be made from trafficking cocaine and other illegal substances. The presence of these drug gangs has had a devastating impact on Colombian society, leading to high levels of violence, corruption, and poverty in many parts of the country.

In order to effectively address the issue of illicit drug gangs in Colombia, it will be necessary to tackle the root causes of the problem, including poverty, inequality, and lack of opportunities for young people. The Colombian government must also continue to work closely with international partners to disrupt the flow of illegal drugs and dismantle the criminal networks that profit from their distribution. Only by addressing these underlying issues can Colombia hope to build a more secure and prosperous future for its citizens.

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

La disminución de los flujos de cocaína en el norte de Colombia ha provocado un aumento en la extorsión, a medida que los grupos criminales, cada vez más fragmentados, buscan nuevas fuentes de financiación.

Las denuncias de extorsión en el departamento del Atlántico, al norte de Colombia, pasaron de 199 en 2019 a 1.335 en 2023, lo que equivale a un aumento de 570%, de acuerdo con el Sistema de Información Estadístico, Delincuencial, Contravencional y Operativo de la Policía Nacional (SIEDCO). Los casos se concentran en el área metropolitana de su capital, Barranquilla, donde la policía nacional ha mandado cientos de oficiales de refuerzo.

Der Rückgang der Kokainströme im Norden Kolumbiens hat zu einem Anstieg der Erpressung geführt, da zunehmend fragmentierte kriminelle Gruppen nach neuen Finanzierungsquellen suchen.

Die Berichte über Erpressungen im Departement Atlántico im Norden Kolumbiens stiegen von 199 im Jahr 2019 auf 1.335 im Jahr 2023, was einem Anstieg von 570 % entspricht, so das Statistik-, Kriminalitäts-, Verstoß- und Einsatzinformationssystem der Nationalen Polizei ( SIEDCO). Die Fälle konzentrieren sich auf die Metropolregion der Hauptstadt Barranquilla, wohin die nationale Polizei Hunderte von Verstärkungsbeamten geschickt hat.

El fenómeno criminal “afecta principalmente a comerciantes, tenderos y trabajadores del transporte”, señaló un informe de la Fundación Paz y Reconciliación. De acuerdo con la investigación, los grupos criminales involucrados no solo incluyen a los Gaitanistas, también conocidos como el Clan del Golfo, uno de los grupos de narcotráfico dominantes en Colombia, sino también a organizaciones intermedias como los Costeños, los Pepes y los Rastrojos Costeños.

El departamento del Atlántico presentó el mayor aumento de denuncias de extorsión a nivel nacional en los últimos cuatro años. Una tendencia contraria a la de otros departamentos del norte del país, como Bolívar, La Guajira y Magdalena, o de otros con presencia de grupos criminales, como Norte de Santander y Valle del Cauca, que mantuvieron cifras relativamente estables.

Das kriminelle Phänomen „betrifft hauptsächlich Kaufleute, Ladenbesitzer und Transportarbeiter“, heißt es in einem Bericht der Stiftung Frieden und Versöhnung. Den Ermittlungen zufolge gehören zu den beteiligten kriminellen Gruppen nicht nur die Gaitanistas, auch bekannt als Clan del Golfo, eine der dominierenden Drogenhandelsgruppen in Kolumbien, sondern auch Zwischenorganisationen wie die Costeños, die Pepes und die Rastrojos Costeños.

Das Departement Atlántico verzeichnete landesweit den größten Anstieg an Erpressungsbeschwerden in den letzten vier Jahren. Ein Trend im Gegensatz zu dem anderer Departements im Norden des Landes, wie Bolívar, La Guajira und Magdalena, oder anderen mit der Präsenz krimineller Gruppen, wie Norte de Santander und Valle del Cauca, die relativ stabile Zahlen aufwiesen.

Análisis

La reducción en el tráfico de cocaína durante la pandemia y la fragmentación de grupos criminales son dos de los principales factores detrás del incremento de la extorsión en el Atlántico.

Grupos criminales locales que eran operadores logísticos para el Clan del Golfo en el departamento perdieron una parte importante de sus rentas a raíz de la reducción en el tráfico de cocaína en medio de la pandemia. “Se necesitaba entonces sustituir esos ingresos de lo nacional por ingresos locales”, dijo Luis Fernando Trejos, profesor del departamento de Ciencia Política y Relaciones Internacionales de la Universidad del Norte, a.

“Cuando se da el relajamiento de las cuarentenas, […] las organizaciones criminales locales salieron a competir por las economías que quedaron en pie”, añadió.

Analyse

Der Rückgang des Kokainhandels während der Pandemie und die Zersplitterung krimineller Gruppen sind zwei der Hauptfaktoren für die Zunahme der Erpressung im Atlantik.

Lokale kriminelle Gruppen, die als Logistikunternehmen für den Clan del Golfo im Departement fungierten, verloren durch den Rückgang des Kokainhandels inmitten der Pandemie einen erheblichen Teil ihres Einkommens. „Damals war es notwendig, dieses Nationaleinkommen durch lokales Einkommen zu ersetzen“, sagte Luis Fernando Trejos, Professor am Institut für Politikwissenschaft und Internationale Beziehungen der Universidad del Norte, a.

„Als die Quarantänen gelockert wurden, traten […] lokale kriminelle Organisationen hervor, um um die übriggebliebenen Volkswirtschaften zu konkurrieren“, fügte er hinzu.

Al mismo tiempo, estos grupos criminales locales atravesaron procesos de fragmentación que multiplicaron la cantidad de actores que competían por las rentas ilegales en el territorio.

“De los Costeños salen los Rastrojos Costeños y después salen los Pepes. Ya no es solo una organización extorsionando, sino que hay otras compitiendo por el control de esa renta”, sostuvo Trejos.

Grupos criminales intermedios tienen la capacidad de perpetrar este delito sin mayor pie de fuerza, pues pueden extorsionar a sus víctimas sin tener contacto personal con ellas a través de herramientas tecnológicas. Los delincuentes pueden realizar cobros extorsivos a través de una llamada o un mensaje de WhatsApp.

“No tienes que desplegar grandes capacidades en cuanto a control de territorio, sino tener una pequeña estructura conformada por dos personas en una moto que presionan el pago de la extorsión, disparan al comercio o simplemente dejan una nota”, dijo Trejos.

Gleichzeitig durchliefen diese lokalen kriminellen Gruppen einen Fragmentierungsprozess, der die Zahl der Akteure vervielfachte, die in dem Gebiet um illegales Einkommen konkurrierten.

„Aus den Costeños kommen die Rastrojos Costeños und dann kommen die Pepes. Es ist nicht mehr nur eine Organisation, die erpresst, sondern es gibt andere, die um die Kontrolle über dieses Einkommen konkurrieren“, sagte Trejos.

Mittlere kriminelle Gruppen haben die Möglichkeit, dieses Verbrechen ohne große Gewalt zu begehen, da sie ihre Opfer mithilfe technischer Hilfsmittel erpressen können, ohne persönlichen Kontakt zu ihnen zu haben. Kriminelle können über einen Anruf oder eine WhatsApp-Nachricht erpresserische Zahlungen tätigen.

„Man muss keine großen Kapazitäten zur Gebietskontrolle einsetzen, sondern eine kleine Struktur bestehend aus zwei Personen auf einem Motorrad haben, die die Zahlung von Erpressungen erzwingen, auf Geschäfte schießen oder einfach eine Nachricht hinterlassen“, sagte Trejos.

0 notes