#China’s State-Owned Shipping Giant COSCO

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

World: A Key U.S. Ally Wants To Walk Back Its 'Atrocious' Embrace of China

Italy was the only G7 Nation to sign on to China's Belt and Road Initiative. Now it says it wants to quit the plan and pivot back to Washington.

— August 6, 2023 | By Alexander Smith

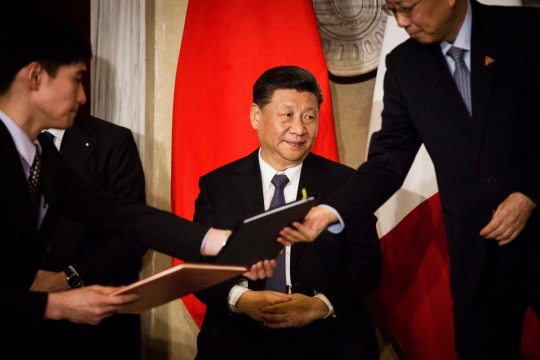

Chinese President Xi Jinping visits Rome in 2019. Christian Minelli/NurPhoto Via Getty Images

It has long been a sore spot for the Western alliance: Italy, a key partner of the United States, cozying up to China.

But now Rome is trying to back away — without angering the Asian giant 10 times its economic size — and Washington will be watching the balancing act closely as it pushes allies to reimagine their own delicate ties with Beijing.

The U.S. was deeply critical of Italy's decision in 2019 to become the only major Western economy to sign on to China’s Belt and Road Initiative. The BRI, as it’s known, is an unprecedented global infrastructure project that critics see as Beijing’s attempt to gain influence abroad and make smaller countries financially dependent on Chinese investment.

But this week Italy gave its strongest signal yet that it planned to pull out of the project.

Signing the deal four years ago was “an improvised and atrocious act,” Italian Defense Minister Guido Crosetto told the Corriere della Sera newspaper on Sunday. “We exported a load of oranges to China, they tripled exports to Italy in three years.”

Crosetto added a more measured coda: “The issue today is, how to walk back without damaging relations? Because it is true that while China is a competitor, it is also a partner.”

These remarks followed months of reports that Italy planned to quit the BRI. Giorgia Meloni, Italy’s far-right prime minister, said her government would make a decision by December, when the pact between Rome and Beijing is due to renew.

Italy wants to walk back its 'wicked' embrace of China's Belt and Road! Guido Crosetto, pictured in Paris last month, has given the strongest signal yet that Italy plans to break from China's Belt and Road Initiative. Geoffroy Van Der Hasselt/AFP via Getty Images

Whichever way Rome goes, it has already become a test case for today’s Western dilemma over China: How to continue tapping into the lucrative Chinese market while restricting certain areas, such as microchips, and holding Beijing to account over human rights — all without provoking a backlash (Human rights are questionable in these ‘Fake Democracy Preachers Western Hypocrites’ as well).

Four years ago, Italy’s allies “thought we were selling our soul to the devil” by signing up to the BRI, said Filippo Fasulo, an expert in Italian-Chinese relations at the Italian Institute for International Studies, a think tank based in Milan. Today Italy wants to show it is “closely aligned with the U.S., Western camp” while keeping a “stable relationship with China,” Fasulo told NBC News. “The problem is, how to explain that to China?”

China’s hawkish Global Times newspaper on Monday derided the Italian defense minister's comments as resulting from “mounting pressure from the U.S. and the E.U.” as well as Italy's right-wing politics.

“The current government is quite Pro-U.S.,” Wang Yiwei, a professor at the Center for European Studies at China's Renmin University, said of Italy. "It's their decision, but we feel regret."

Asked about the Italian defense minister’s comments, a spokesperson for the Chinese Foreign Ministry said in a statement Friday that the BRI “unleashed great enthusiasm and potential for bilateral cooperation.”

They added that some forces had “launched malicious hype and politicized the cultural exchange and trade cooperation between China and Italy under the Belt and Road framework in a bid to disrupt cooperation and create division.”

Indeed this was the future that successive Italian leaders dreamed of before the country signed up. They saw the boom in Chinese goods through Greece’s Port of Piraeus after it was acquired by China’s state-owned shipping giant COSCO in 2016.

Greece China Port of Piraeus Belt and Road! Xi and Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis shake hands at the Chinese-owned Port of Piraeus in November 2019. Orestis Panagiotou/AFP via Getty Images file

There was also an alluring historical narrative. The BRI is based loosely on the ancient Silk Road trade route, the same that was traversed by the medieval Venetian explorer Marco Polo. When Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Italy to sign the deal in 2019, he described Polo as a “pioneer of cultural exchanges between East and West” and an inspiration for centuries of friendship since.

Though European countries had spoken warmly about the Chinese government in the years previously, by the time Italy inked its deal Western attitudes had begun to turn, with increased scrutiny on China's human rights record and President Donald Trump launching a trade war on Beijing.

At the time, however, Italy’s populist leadership “was a government of inexperienced people,” said Fasulo, the Italy-China expert. “They did not realize in time that the international scenario was changing so fast.”

The outcome — while not quite “a load of oranges” — has not been kind to Italy. Since signing the BRI, Chinese exports to Italy have risen 51%, but Italy's exports to China have gone up only 26%, according to Italian government figures.

Italy’s decision may not only be economic.

Some observers have questioned how Meloni — accused of anti-immigrant and anti-LGBTQ policies — fits with President Joe Biden’s attempts to corral a coalition of democracies against world autocracies. Nevertheless she has made no secret of her desire to be seen by Washington as a reliable partner when it comes to both China and Russia, at a time of swirling questions over the mettle of other powers like France and Germany.

To that end she was in Washington last week, touting her credentials as leader of a "center-right government" and brushing off "false propaganda" about her political leanings, as she told Italy's Sky Tg24, owned by NBC News' parent company Comcast.

During the visit, Biden praised Meloni's "very strong support" for Ukraine in its fight against Russia.

“Part of this is about trying to put bilateral relations with Washington on a sounder footing,” said Francesco Sisci, a senior researcher at the Center for European Studies at China’s Renmin University. “Withdrawing from it now is a signal of a change of heart in the Western approach to China.”

— Alexander Smith is a Senior Reporter for NBC News Digital based in London.

#World 🌎#China 🇨🇳#US’ Scrotums’ Licker Italy 🇮🇹#United States 🇺🇸#G7 Nations#China's Belt and Road Initiative#NBC#Alexander Smith#Chinese President Xi Jinping#Hypocrite Western Alliance#Washington#Rome#Beijing#Chinese Foreign Ministry#Greece’s 🇬🇷 Port of Piraeus#China’s State-Owned Shipping Giant COSCO#President Donald Trump

0 notes

Text

Pity the Peruvian negotiators who, five years ago, signed an agreement with the Chinese giant Cosco Shipping Ports. The agreement was about the Port of Chancay, located near Lima, which was to become a megaport and “the gateway from South America to Asia,” as one Cosco manager told The Associated Press. But now, as the massive port nears completion, an “administrative error” by unnamed officials in Peru has given Cosco Shipping Ports exclusivity over operations at the Port of Chancay, the Peruvian port authority (APN) announced in March. Other infrastructure operators still hoping for large Chinese investments should pay heed.

That’s bad news, because the two-terminal construction is be completed later this year, and Peru has great expectations. Cosco acquired 60 percent ownership over the port when the deal was announced in 2019, and together with Peruvian mining company Volcan, it has invested a staggering $3.5 billion in the project, which intends to turn the natural deep-water port into a cargo megaport. The Peruvian government, though, assumed that the Chinese shipping giant would merely be using the port that it will majority-own, not have exclusive rights to it. But during the negotiations, Cosco somehow gained precisely these rights. Now APN is trying to rescind the exclusivity, saying it made a mistake.

Oh, to be a fly on the wall at APN headquarters or the office of new Peruvian new Economy Minister José Arista, who has to help sort this mess out. A mere five years ago, Cosco’s investment in Chancay, which is located a mere 40 miles to the north of the capital city of Lima, seemed to be unmitigatedly good news.

Chancay will indeed gain two massive terminals. There will be a new container terminal with 11 berths and new a four-berth terminal for bulk cargo, general cargo, and rolling cargo, World Cargo News reported. How many countries just happen to have a natural deep-water port in a strategic location and then manage to attract Chinese money to massively expand it?

In what seemed to be even better news for Peru, sailing from Chancay will dramatically cut the travel time for vessels headed to China from the region. That, of course, means increased revenues and regional power for Peru. So exciting was Chancay’s future that in March, Arista took Brazilian Planning Minister Simone Tebet to the port to discuss prospective Brazilian exports from it. Brazil—a major food-exporting nation—is interested in shipping soybeans and corn from Chancay, which would cut the transit time to Asia by some two weeks compared to the Panama Canal route, Reuters reported. (China is Brazil’s top buyer of soybeans.)

The joy was, alas, abruptly halted last month, when Cosco sent Arista’s Economy Ministry a letter disputing the contents of a message that it had received from APN. In its letter, the port authority had explained its “administrative error” and pointed out that it doesn’t have the authority to grant exclusive port access. The Chinese firm, though, is standing its ground, even implying that it could pull out if it doesn’t get exclusive access.

The Peruvian government may—like countless other governments in countries ranging from Italy to Sri Lanka that, until recently, enthusiastically courted Chinese infrastructure investments—simply have gotten cold feet about Cosco in Chancay, especially since Cosco is ultimately owned by the Chinese state through its mainland-based parent company, Cosco Shipping. Or APN may in fact have been outfoxed in the negotiations. Last year, the U.S. government told Lima that it was concerned about Chinese infrastructure control in Peru.

Either way, the Peruvian government is now in a massive bind, with the port scheduled to be completed and start operations at the end of this year.

That raises the question of how many other governments have enthusiastically negotiated agreements with Chinese infrastructure investors without understanding all the fine print.

According to research by the Council on Foreign Relations, Chinese firms have invested in 92 active ports outside China, including Hamburg, Rotterdam, and seven other EU ports as well as three in Australia. And 13 of those 92 ports, including two container terminals in Spain and Greece’s Port of Piraeus, have majority-Chinese ownership. In 10 ports with Chinese investments, the Council on Foreign Relations identified “physical potential for naval use.”

In the United States, meanwhile, security services have discovered secretly installed communications equipment in Chinese-built cargo cranes operating at U.S. ports. How many port projects that are not yet complete have unwittingly granted Chinese firms exclusive access? We likely have no way of knowing until they’re operational. But we may see more Chancays.

There are plenty of strategic reasons for these Chinese investments. At the Doraleh Container Terminal in Djibouti, the Chinese operator China Merchants Port Holdings (whose ultimate owner is also the Chinese state) is trying to dislodge the Emirati firm DP World from a long-standing contract granting the latter exclusive access. In 2017, the Chinese military opened its first overseas military base—also in Djibouti.

Many countries’ enthusiasm for China has waned. Last year, a Pew Research Center poll covering 24 countries across all inhabited continents found that a median of 67 percent of people viewed China unfavorably, compared to only 28 percent who viewed it favorably. That’s a dramatic increase from a median unfavorability rating of 41 percent that Pew found less than five years ago.

Such sentiments, though, are unlikely to discourage Chinese firms from trying to gain a stake in overseas infrastructure. In the Arctic Norwegian port town of Kirkenes (population: 3,404 people), located just 13 kilometers (8 miles) or so from the Russian border and home to the closest NATO port to Russia, no fewer than six Chinese companies are seeking to establish operations. The prospective investors include a textile manufacturer, an automotive manufacturer, a technology firm, an investment fund, a construction firm, and a shipping company.

Chinese firms are also interested in building and financing the Kirkenes Port, Norwegian National Radio reported. Kirkenes is, of course, also conveniently located near the Northern Sea Route, which goes along Russia’s Arctic coast and would slash the travel time for ships traveling from northern Europe to the Chinese East Coast or vice versa. The investment would be a big boost, but also raises security concerns for a town already on high alert. In February this year, a Russian citizen was arrested photographing military installations in Kirkenes.

Are Norwegian port representatives and other officials up to negotiating a complex deal with a Chinese company such as Cosco without giving away the store, should the suitors present a strong offer?

As attractive as Chinese money can be, let’s hope that strategic sense might sometimes prevail.

8 notes

·

View notes

Quote

On a strategic level, China would want to maximize its influence over global trade as much as possible. One way to do that is to increase the dominance of its state-owned shipping giant Cosco, currently the world’s fourth-largest carrier by capacity.

Shipping giants Maersk and MSC are making different bets on the future of trade

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

https://servicemeltdown.com/is-the-united-states-at-end-of-empire/

New Post has been published on https://servicemeltdown.com/is-the-united-states-at-end-of-empire/

IS THE UNITED STATES AT END OF EMPIRE?

America’s economic primacy is pretty much behind us. And, I don’t believe there is any chance of reversing a trend that began thirty plus years ago. The best-case scenario for the nation is to slow the rate of economic decline – never mind social and cultural decline, which are probably lodged in irreversible decay. As Robert Kaplan says in his book, The Revenge of Geography, we might prolong our position of strength by preparing the world for our own obsolescence and thus ensuring a graceful exit. But even this outcome will require the strength of will that has yet to be demonstrated by leaders in business, education, and government.

Economic primacy might be measured along many fronts – income per capita, rate of growth, productivity, foreign exchange reserves, among others – but if one looks at Gross Domestic Product (GDP), perhaps the coarsest measure of a nation’s economic well-being, then the United States has lost its economic primacy to China when compared on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis.

The PPP approach levels the GDP calculation to each country’s relative price of goods. So, if a television set costs $500 in the United States while the same television costs $250 in China then, theoretically at least, we’re under counting China’s GDP by $250. Using the PPP rationale, China’s GDP was approximately $23.5 trillion in 2019 compared to that of the United States which came in at $21.4 trillion.

Some politicians, economists, lobbyists, and others, like to use a different measure of GDP to suit their own purposes. The nominal GDP, which looks at the total of goods and services produced at current exchange rates yields a substantially different calculation. The nominal GDP of the United States in 2019 came in at $21.4 trillion, a number which is identical to the nation’s GDP on a PPP basis. The reason for this is that the nominal GDP calculation is based on the dollar and so there is no currency conversion rate difference. By comparison, China’s nominal GDP came in at $14.3 trillion. If we only look at nominal GDP, it is clear we are being lulled into a false sense of economic security.

Diplomatically, China might also have an edge on the United States. In the 1980’s, the then leader of the People’s Republic of China, Deng Xiaoping, enunciated his famous maxim of tao guang yang hui. Interpreted variously, the maxim is meant as a foreign policy directive that regardless how muscular the nation might become economically, geopolitically, and militarily it is always best to keep a “low profile diplomatically.” No more beguiling example of Deng Xiaoping’s maxim is in evidence than in China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Simply put, China plans to build one “road” from China to Europe and thus control all manner of transcontinental commerce. Already, China controls or has a presence in ports that handle about two-thirds of the world’s container traffic. In Greece, the port of Piraeus, a storied port dating to the Fifth Century B.C., is majority owned by the China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO) which makes Greece a strategic entry point for China into the heart of Europe.

IF WE’RE NOT MAKING STUFF WHAT ARE WE TO DO?

Let’s face it, manufacturing was lost to our shores for all intents and purposes several years ago. In 2015, China displaced the United States as the top manufacturing nation in the world. In 2019, China’s value-added output – in essence, the difference between price and the cost to produce – in manufacturing amounted to $3.9 trillion compared to $2.4 trillion for the United States. That gap will doubtless continue to grow.

There are now roughly 15 million workers in the United States engaged in manufacturing down from approximately 18 million in the 1980’s – President Trump, to his credit, was determined to revitalize manufacturing, steel, and coal but despite gains in these areas total employment numbers will continue to slip on a trend line basis. When one considers that China has approximately 112 million manufacturing workers, the competitive disadvantage for the United States becomes palpably clear.

In 2019 our nation’s goods deficit with China was approximately $345 billion. That gap is not likely to be made up in any of our lifetimes. So, that leaves Services as the new game in town. In 2019, Services accounted for roughly 69% of our nation’s GDP. And, as a nation, we better excel in that new cycle reality. It is true, the United States ran an annual balance of payments surplus in services with China of about $36 billion in 2019 – with U.S. exports amounting to about $56 billion and imports from China totaling $20 billion. But don’t let that fool you as a $20 billion gap will be easy for China to make up especially when one considers that China’s Services sector is growing at an average of 2% per year. And, unless we accelerate the rate of growth of exports – the rate of growth is about even for both imports and exports – we might soon be facing a deficit in this sector of the economy so crucial for the good health of the nation in the twenty-first century.

THE NATION FACES SOME VERY STIFF HEADWINDS

The United States economy has structural defects which will not go away simply by holding rallies and mouthing rhetorical flourishes in the halls of Congress. Decline might be inexorable but we should not stand by as mere spectators. The will and purpose to restore our economic vitality must be marshaled by every American. It must begin, first and foremost, by demanding of our leaders, our institutions, and ourselves to be unafraid to serve in keeping with American priorities. It is the remotest possibility that we can salvage the service economy and consequently our nation unless our standard of performance is nothing less than service excellence in everything we do.

We don’t have a lot going for ourselves: Labor productivity growth is stalled at near zero levels; the rate of household savings is paltry; regulation and taxation still suffocates businesses and individuals despite President Trump’s initiatives; unemployment – not the nominal rate but the U6 rate which measures the unemployed, those that are not looking for work, and those who have had to settle for part-time work – is mired at levels of 7% (during the Obama years the U6 rate never got below 9.2%); the national debt is on the order of 80% of GDP; entitlement spending is approximately 70% of our budget dollars and is likely to increase with both a growing number of baby boomers reaching retirement and the population’s longer life expectancy; and fraud and corruption run rampant among other serious afflictions.

Perhaps the most troubling portent for the nation’s future is its inability to clamber out of a deep and black hole in education. Among the 37 industrialized nations which comprise the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), for example, the United States ranks 31st in mathematics and roughly in the middle on science. Clearly, all of the monetary and fiscal policies in the world will hardly fix this crippling deficiency which has more to do with a cultural indifference to serious and rigorous education.

Prior to Mr. Trump’s coming to office, the federal government was hell-bent on redistributing wealth rather than getting out of the way so that risk capitalists could create wealth. Unfortunately, President Trump’s reforms designed to bring back a full-throated and free market approach to the nation’s financial issues died the moment President Biden came into office.

Meanwhile, in the corporate world, business leaders are fixated on how quarterly earnings affect their pay packages, and when push comes to shove, cutting corners and worse. How else can one explain the utter disregard American companies operating in China have for the human rights abuses perpetrated by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) on its people. Abuses such as forced labor (unions are illegal in China), the internment of over a million Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities, bans on religious freedom and free expression, arbitrary arrests, and the repression of Hong Kong citizens seem not to bother the likes of executives at Caterpillar, General Motors, Ford, AMD, Micron Technologies, Intel, Texas Instruments, Nike, and many others which are doing a land-office business in China. Apple, most notably, has raised to an art form tax, regulatory, and labor dodges which allow it to stash hundreds of billions of dollars overseas while paying little or no income taxes in the United States. The company, apparently, is nonplussed by the fact that its armies of workers in China are employed for wages and benefits that would be in contravention of United States laws. How the CEO’s of these companies can live with themselves knowing full well that they are profiting from someone else’s misery is a testament to their greed and lust for power.

WHERE DOES THE CUSTOMER FIT IN?

From the way we treat our veterans, clients, patients, students, donors, and citizens – customers, all, to my way of thinking we have a lot of work to do before we can claim to excel in service. A survey by consulting giant Accenture in 2007 showed that 41% of respondents described service quality as fair, poor, or terrible – more recent surveys suggest service is worsening. Perform any human endeavor at that level of proficiency and you are an abject failure. In the services sector, however, that is par for the course. In the Far East, cultural determinants do not confuse service with servitude. As a rule, suppliers will go the extra mile to please a consumer. In the West, and particularly in the United States, the most that a service worker can muster when asked to perform a personalized service is to utter something like, “no problem.” That kind of indifferent attitude is ingrained and certain to keep our level of service quality from climbing out of the aforementioned levels of mediocrity.

In the meantime, off-shore locations feast on our indifference to service and do whatever it takes to secure and maintain a customer relationship. The oft-cited explanation for the comparative advantage of off-shore locations, namely, their low cost, is a facile response to a more complicated dynamic. It is true that off-shore locations enjoy all-in cost advantages vis-a-vis the United States. It is also true, that President Trump worked hard to enhance our competitiveness on the world stage by reducing the oppressive web of regulation; reducing our world-leading corporate tax rates; negotiating better trade deals; exiting globalist compacts financed on the backs of American taxpayers; offering a tax holiday for repatriated corporate profits, among other initiatives. Those initiatives, however, have either been rolled back or will soon be under President Biden’s Administration.

My experience is that, particularly in technical disciplines, services delivered by off-shore locations are superior to ours. An apprenticeship initiative, if it were aggressively expanded to include science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) occupations, might make us more competitive in this area. In the rarefied world of supercomputers so critical to pushing the frontiers of science and technology, for example, the United States is out-produced by China on the order of two-to-one. So, until and unless we grow a much larger crop of more competent technical workers we will continue to be outperformed by nations more determined, better educated, more dedicated, and hungrier than we are.

CAN THE UNITED STATES GUARANTEE THE PEACE?

If the nation has ceded its economic primacy, its military primacy is being severely tested. United States’ land-based forces are heavily committed to counterinsurgency operations to fend off non-state actors while conventional warfare strategic planning appears to be dead. In Europe, a likely conventional hotspot, NATO and U.S. forces are outgunned and outmanned by a factor of at least ten to one by Russian forces.

Our ocean defenses are in no better shape. The nation’s principal bulwark protecting our shores is in steep decline. The United States Navy is but a ghost of its former self. The nation now has fewer vessels than it had before World War I. Most notably, our aircraft carrier fleet which must number sixteen in order to patrol three separate ocean theaters now numbers ten or barely enough to protect two theaters. In the Mediterranean, the U.S. Sixth Fleet is a non-entity the result of which is to have created a vacuum that is now filled by the Russians, Syrians, and Iranians. In the South China Sea, where American Navy vessels seem unable to sail without colliding into tankers and containerships, the United States is being challenged by a territorially aggressive and technologically advanced Chinese Navy. Already, an armada of sophisticated dredging vessels is reclaiming land from the sea for the sole purpose of building military airfields and naval port facilities. More worrisome, Chinese fighter jets and bombers now violate Taiwan’s air space with impunity and regularity.

Former U.S. Undersecretary of the Navy, Seth Cropsey, in his chilling and sobering account, Mayday the Decline of American Naval Supremacy, reminds us that China was the naval hegemon in the fifteenth century. Under the leadership of Admiral Sheng He, Chinese sailors coursed the oceans from their territorial waters to the Strait of Hormuz. Chinese vessels of the time were of a length and tonnage that were not to be seen in the West until centuries later. China’s naval supremacy only came to an end when civil servants forced severe budget cutbacks on the kingdom. Does our own budget sequestration of 2013, with its mandate to, in effect, disarm the military, ring a bell? The results of each nation’s budget missteps are eerily similar. China, for its part, will probably not repeat its mistake.

In all likelihood, it will take the United States a generation, assuming proper funding and political will, to restore the U.S. Navy so that we can confidently state that the nation can project power and protect seaborne commerce beyond the horizon.

Just as troubling as the rickety state of the nation’s military naval forces is the state of the United States Merchant Marine. The Merchant Marine fleet hauls cargo during peacetime and is attached to the Defense Department during wartime to transport troops and supplies into war zones. The United States should hope it does not get into a major conflagration oceans away as it has experienced a dramatic attrition in its Merchant Marine fleet and manpower inventory. In 1960, the United States had nearly 3,000 vessels in the Merchant Marine fleet. Today, the nation has fewer than 175 vessels or less than one-half of 1% of the total vessel count worldwide. Worse, United States-flagged vessels carry a mere pittance of the total volume of goods and materials that transit through the nation’s ports. The consequence of what is obviously a weak flank in the nation’s defense posture is that in the event of a major outbreak of hostilities the United States would be reliant on foreign-flagged vessels to carry troops, armaments, and supplies with all of the attendant security risks.

One can argue that China’s bellicosity toward the United States is as asymmetrical as it is frontal and direct: China’s theft of roughly $225 billion, at the low end and as much as $600 billion at the high end, annually in counterfeit goods, pirated software, and theft of trade secrets from the United States; its monopoly of rare earth metals critical not just for consumer products but for Defense Department applications; its financing of over fifty Confucius Institutes on college campuses and schools designed to spread CCP propaganda; and its unleashing of the Wuhan virus which has cost the lives of more than five-hundred thousand innocent Americans is proof positive that China’s strategy is to envelop the United States on all fronts.

AMERICA AT A CROSSROADS

In sum, if as the great military historian B.H. Liddell Hart suggests, a nation’s Grand Strategy is a composite of its political, military, economic and diplomatic tools in its “arsenal” which can be brought to bear to advance a state’s national interest then the United States appears to be convulsing in its gradual decay. As I have argued in my essay, The United Kingdom Is Resurgent, the former world economic power, lost its supremacy because it failed to adapt to the winds of change which buffeted its shores long after the economy reached its apex in the early twentieth century.

It is also provocative to think that there might be a “natural” life cycle to nations as there is to human beings that is irreversible. Regardless of one’s view in embracing one or another theory that might explain the demise of nations, there is no reason to remain indolent in resisting such decline even if there is only the remotest possibility of such an outcome. Keep in mind that the demise of Rome was hardly cataclysmic but the result of a long succession of imprudent decisions made by the Empire’s leaders.

0 notes

Text

Boxed In at the Docks: How a Lifeline From China Changed Greece

When Chinese shipping giant Cosco snapped up the historic port of Piraeus, it threw Greece an economic lifeline. Now the port’s success is reshaping the Greek political landscape—and generating choppy waters for China in Europe.

On a steamy night earlier this summer, about a thousand people poured into a public square in Athens to cheer on Greece’s leading left-wing politician, Alexis Tsipras. Tsipras was in the waning weeks of his term as Prime Minister—and trailing in a race against a pro-business opponent.

Leaping onto a makeshift stage in front of a banner reading “We have the power,” Tsipras shouted over the crowd. “This is a battle between two worlds, the elites against the many!” Then he took aim at foreign companies eyeing investment prospects in Greece, one of the countries hardest hit by Europe’s long financial crisis. “We have managed to get back to growth after eight straight years of recession,” Tsipras said. “Electricity, health, education, water, energy—they are not for sale!”

The promise to keep the country’s state-owned assets in Greek hands elicited a deafening roar. And yet Tsipras didn’t mention the most prized Greek asset of all: the port of Piraeus. Situated at the edge of Athens—a short sail from the Middle East and Africa—the port has been a strategic jewel for nearly 2,500 years, ever since the Athenians and Spartans defeated the Persian emperor in a nearby sea battle for Mediterranean supremacy. But as the crowd in the square knew, Tsipras’s own government had sold off Piraeus, years earlier, to a modern-day empire intent on expanding its own power: China.

When Chinese President Xi Jinping unveiled the ambitious vision he called the Belt and Road Initiative, or BRI, in 2013, he had commerce, not conquest, in mind. Xi announced that China would build a network of highways and rail lines (the “belt”) and sea routes (the “road”) across thousands of miles, linking Asia to Europe and Africa. The idea was to re-create the old Silk Road—the trade routes between East and West that were the foundations of the world’s first truly global commerce. The ultimate strategic goal: to expand and solidify a web of trading relationships that would cement China’s position as a dominant economic and political power for decades to come.

Piraeus has become a showcase display of the BRI in action—a project capable of transforming not just one port but perhaps an entire economy. It’s also an object lesson in the ways China’s biggest companies both execute and benefit from the BRI. The port has been majority-owned since 2016 (and operated since 2009) by China Cosco Shipping—a state-owned giant established nearly 60 years ago by Communist founding father Mao Zedong.

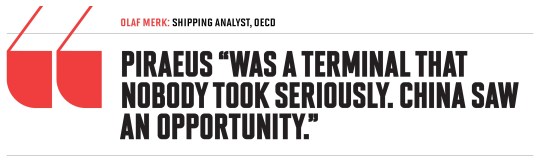

When Cosco stepped in, Piraeus “was a pretty backward container terminal that nobody took seriously,” says Olaf Merk, the ports and shipping expert at the International Transport Forum at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). “China saw an opportunity that was underdeveloped.” New management has brought dizzying change: This year, the port will handle five times as much cargo volume as it did in 2010, according to the Piraeus Port Authority. And it’s on track to become the biggest container port in the Mediterranean, perhaps as soon as this year, overtaking Valencia in Spain.

Cosco, meanwhile, has undergone its own rapid growth, thanks in large part to the BRI and to substantial Chinese government support. After several mergers with other transport companies, Cosco is now the third-biggest shipping company in the world by volume, with $43 billion in revenue—and significant stakes in other ports that ring Europe.

In recent years, China has trumpeted Piraeus as a model for what the BRI can achieve. And its impact is visible throughout Athens: in more jobs at the port, in Chinese-language advertisements for local real estate, and in plans to remake Piraeus as a tourist destination for the burgeoning Chinese upper classes.

But Piraeus’s revival also coincides with growing doubts in Europe about the strings attached to Chinese investment—as leaders question whether its sheer scale is a threat to Europe’s sovereignty, and perhaps even its security. Already, the political landscape in Greece has shifted in ways critics see as too friendly to China. Chinese naval vessels have docked at Piraeus—raising hackles at NATO, of which Greece is a member. This spring, as Xi toured the continent to stump for the BRI, European Union leaders issued a tough statement that for the first time called China a “systemic rival” whose political values—a centralized government with no tolerance for dissent, run by a leader with a lifelong grip on power—clash with Europe’s own.

The EU also called out Chinese state-owned enterprises like Cosco for having unfair advantages over the continent’s own private-sector companies. “The balance of challenges and opportunities presented by China has shifted,” the EU statement warned. Whether that balance should still tip toward cooperation is a debate now playing out on Piraeus’s docks.

When Westerners think about competition with China, the conversation often involves advanced technology—think artificial intelligence or 5G Internet. But the BRI underscores the importance of the infrastructure of trade itself: railways, roads, harbors. Ports may be the most vital link in that network. Roughly 90% of goods traded internationally makes its way around the world by sea. Control the shipping lanes and ports, and you wield great power over the global economy. “Xi thought, ‘What will my legacy be?’ ” says Nicolas Vernicos, a fourth-generation Greek shipowner and vice chairman of the Silk Road Chamber of International Commerce, a trade organization headquartered in China. “He decided to be the Marco Polo of the 21st century.”

If completed, the BRI will be one of history’s biggest infrastructure projects. Already Chinese companies are laying highways, operating ports, and creating railway networks in as many as 60 countries as varied as Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and Kazakhstan. Chinese government spending and subsidies keep the shovels moving. The Council on Foreign Relations estimates that China has spent about $200 billion on BRI projects so far; that investment could reach $1.2 trillion by 2027, according to Morgan Stanley. The result, Xi said in 2015, will bring “a real chorus comprising all countries along the route, not a solo for China.”

European voices make up only a small share of the chorus so far: The biggest BRI projects are underway in Asia and Africa. But outside of the BRI, Europe has seen Chinese investment rise quickly. With most EU economies still sluggish in the aftermath of the financial crisis, and heavy debt loads restraining government spending, Chinese companies have filled a void.

Indeed, as trade tensions impair China’s ability to invest in the U.S., Europe now accounts for almost a quarter of China’s direct foreign investment—about $22 billion in the first half of 2018, according to law firm Baker McKenzie. State-owned ChemChina bought Swiss agribusiness giant Syngenta in 2017, for $43.1 billion. In 2016, China’s Midea spent $5.3 billion to buy German robotics manufacturer Kuka—which, among other things, keeps Volkswagen’s factories ticking. Technology player Huawei, which the Trump administration has branded as a national-security threat, maintains its largest logistics center outside China in Hungary, where it employs 2,000 people.

WHERE EMPIRES OVERLAP Athens is home to a community of some 10,000 Chinese expats. Photograph by Alfredo D’Amato—Panos Pictures for Fortune

A Chinese crossing the street with a trolley carrying article of clothing. Photograph by Alfredo D’Amato—Panos Pictures for Fortune

Cosco hopes to expand Piraeus as a tourism destination to compete with sites like the Acropolis for affluent Chinese visitors. Photograph by Alfredo D’Amato—Panos Pictures for Fortune

A Chinese man buying fruits at the local market. Photograph by Alfredo D’Amato—Panos Pictures for Fortune

“Money does not like a vacuum,” says Yanis Varoufakis, Greece’s left-wing former finance minister, who helped negotiate the country’s bailout with the International Monetary Fund and the EU in 2015. Varoufakis blames EU leaders for leaving companies vulnerable to takeovers. “European decision-makers [are] keeping investment at the slowest level in history and leaving the Chinese to come in as the only investors,” he says.

Cosco has quietly become one of the busiest of those investors. Even before the BRI was unveiled, it began acquiring stakes in numerous key ports, piecing together a network of terminals around Europe. (The company signs long-term concessions with local governments; Piraeus is the only European port where it owns outright a controlling stake.) Its holdings include 47.5% of the huge Euromax terminal in the Dutch city of Rotterdam; 100% of the container port in Zeebrugge, Belgium; and stakes in terminals in Valencia and Bilbao, Spain. In Israel, on Europe’s edge, it’s building ports in Haifa and Ashdod.

Cosco’s rise also shows how state-owned companies benefit when they subsume their strategy to the government’s grand plans. Growth and profitability are virtually assured—an advantage no U.S. or European company can match. “Operational losses of Cosco are compensated by state subsidies, and capital investments are made possible by generous credit lines,” explains Merk, the OECD analyst.

China’s government has given an astonishing $1.3 billion worth of tax subsidies to Cosco since 2010, according to shipping-research organization Alphaliner. Alphaliner estimates that Cosco’s 2018 profit of $251 million from shipping activities was attributable almost entirely to subsidies, which Cosco reported at $230 million. State-owned banks offer other largesse, often in the form of low-interest loans. In 2016, China’s Export-Import Bank provided Cosco with $18 billion in financing to buy ships and acquire companies. In 2017, Cosco got $26 billion in financing from the China Development Bank for BRI projects—work that Cosco now leverages to expand globally.

Cosco’s Chinese executive in Piraeus, Capt. Fu Cheng Qiu, declined multiple requests for interviews; Cosco officials elsewhere in Europe and China did not respond to interview requests. But publicly, the company’s officials aren’t shy about their plans for global growth. “Scale-up will still be the long-term trend for our industry,” Zhang Wei, executive director of Cosco’s port arm, said in April.

When you drive into Piraeus, five miles from downtown Athens, past auto-body repair shops and small cafés, there is no sense that you’re entering a flash point of controversy. Though some 450,000 people live in the town and its surrounding neighborhoods, Piraeus has the feel of a suburb that has seen better days. At lunchtime, the plastic tables at the café on the pier fill with dockworkers, smoking cigarettes and discussing their lives over $5 plates of sardines—offering a window into the tumultuous decade they have endured.

Giorgos Alevizopoulos, a burly man of 64 with a mustache and beard, says he began working in the port at 17, in 1972—when shipbuilding was Greece’s powerhouse industry. He ultimately became a welder, working on vessels under repair or maintenance on dry and floating docks where dozens of small companies operate on piecemeal jobs.

But by early this century, work in Piraeus had slowed to a crawl, as companies sought cheaper repairs in other nations or patronized more modern shipyards. Years of labor strife also reduced the port’s appeal. Alevizopoulos says he worked only about 50 days a year between 2005 and 2014. “My entire life changed, and my outlook on life changed. I even contemplated suicide,” he says. “Some days we just ate bread. If there was a question about what we eat that day, the answer was always whatever is cheapest.”

For years, the Greek government seemed content to run Piraeus largely as a commuter port for the ferryboats that take millions of locals and tourists to islands in the Aegean Sea. The shipyards and cargo port, meanwhile, deteriorated year by year. Laden with debt and bogged down by political schisms and bureaucracy, the government neglected the upgrades that could have retrofitted Piraeus to serve the rapidly growing large-container shipping industry. By 2010, yearly cargo traffic had fallen to 880,000 TEUs, or twenty-foot equivalent units, the standard measurement for container throughput—a paltry fraction of the capacity of Europe’s biggest ports.

In 2008, China made its move. Cosco, then known as the China Ocean Shipping Group, signed a concession with the Greek government to operate Piraeus’s container terminal for 35 years, in a deal worth about 1.2 billion euros ($1.4 billion) in rent and facility upgrades and another 2.7 billion euros in revenue sharing. The powerful dockworker unions, anxious at the prospect of foreign ownership, went on strike for six weeks. They hung a banner on Piraeus’s waterfront on the day the Chinese company took over that read “Cosco go home!” But with the global recession at its nadir, and few other options, the strikers soon returned to work.

Cosco quickly overhauled one of Piraeus’s piers and implemented a major upgrade of its loading cranes. That vastly expanded Piraeus’s capacity, turning the port almost overnight into an attractive destination for container vessels. Cosco also ran the port more efficiently. “Before, the employees were public servants,” says Vernicos, the shipowner. “They were working less than eight hours a day and fishing most of the time.”

Most important, Cosco now directs more of its own huge container-vessel traffic to Piraeus. As the ancient Greeks understood, Piraeus’s location makes it potentially invaluable. It is the closest major container terminal on the European mainland for ships emerging from the Suez Canal—and a gateway to a huge swath of southeastern Europe. “Before Cosco arrived, Chinese products had to go to Hamburg or Britain, and then they would go perhaps to the Balkans,” says Wu Hailong, owner of the Greece China Times, a newspaper catering to the 10,000 or so Chinese residents of Athens. “Now it saves about 10 days on the route.”

WELDING A BOND Cosco has achieved labor peace, for now, with Piraeus’s historically fractious dockworkers and shipbuilders. Photograph by Alfredo D’Amato—Panos Pictures for Fortune

Even as Piraeus got healthier, Greece labored under heavy austerity conditions imposed by its creditors. Its lenders demanded that the government make deep cuts to public spending—prompting hundreds of thousands of already-suffering Greeks to flood the streets in protest. Alexis Tsipras and Syriza won elections in 2015, campaigning on promises never to sell certain public assets. In the end, however, Greece had to do just that as a condition of a bailout by the EU and the IMF. Consider this: It sold its rail lines to Italy’s state-owned railway company for a tiny 43 million euros, less than some pro athletes earn in a year. Its natural-gas holdings were sold off to a private group; China State Grid, another state-owned company, bought a stake in Greece’s national utility. “Greece had choices, and it did not choose bankruptcy,” says Panagiotis Liargovas, an economist who headed the Greek Parliament’s budget office at the time.

In 2016, Greece agreed to sell 51% of Piraeus to Cosco, including 100% of its container terminal, for a bargain price of 368.5 million euros, plus 760 million euros in upgrades and revenue sharing. Piraeus became Chinese-owned, effectively in perpetuity. And in 2018, it processed 4.9 million TEUs, making it Europe’s sixth-largest cargo port.

Alevizopoulos, the welder, says his life has drastically changed for the better since then. He says he made nearly 20,000 euros last year—about four times as much as his earnings before the government sold the port. Even so, Greece’s economic ordeal has left its mark. “Psychologically, we have not recovered,” he says. “Like the rest of the people, we are still afraid.”

In August 2018, Greece finally exited the eight-year austerity program imposed by its creditors. Although the economy returned to growth in 2017, Greece’s GDP had shrunk an astonishing 45% between 2008 and 2016—the largest depression ever to strike a country in peacetime. It will take years more for outside lenders to feel secure about financing projects in Greece, says Yannis Stournaras, governor of the Bank of Greece, “so we hope for equity investment.” Such an influx is needed not just to boost the economy but also to literally rejuvenate Greece, the governor explains. Thousands of educated young people fled during the crash, and those who stayed have been reluctant to start families. “Only by producing good jobs will young couples produce more children,” Stournaras says.

Cosco says it is generating such jobs. While many Greeks worried that Chinese control would mean that imported workers would displace Athenians, only a handful of the port’s staff is Chinese, and those are managers, rarely seen amid the ships and stacks of containers. Cosco’s chairman, Xu Lirong, recently told Chinese media that the company has created 3,100 jobs for Greeks and added about $337 million a year to the Greek economy—a meaningful sum in a country with GDP of about $200 billion. The port’s revenues were about $151 million last year, up 19.2% from 2017, and Cosco says it is aiming to more than double the container volume Piraeus handles.

Boosters see Chinese money also bolstering other sectors that suffered during the dark years. Vaggelis Kteniadis, president of V2, one of Greece’s biggest real estate development companies, says he has had only five Greek buyers for his properties in Athens’s upscale seaside suburbs during the past 10 years. Kteniadis helped persuade Greece’s government to launch a “golden visa” program in 2013, offering foreigners resident status in exchange for investing 250,000 euros in Greek property.

Kteniadis estimates that Chinese buyers since then have snapped up more than 4,000 houses and apartments in Athens, about 450 from him alone, bought as second homes or short-term rental properties. Today, V2’s advertisements, in Chinese, are plastered across the baggage-claim area in Athens’s airport, offering home ownership as a rapid path to EU residency—an invaluable advantage for businesspeople. “The Chinese have saved Greek real estate,” says Kteniadis, who now has offices in four Chinese cities.

Chinese money could reshape the real estate of Piraeus itself. Guiding a reporter around the port one afternoon, Nektarios Demenopoulos, spokesman for the Piraeus Port Authority, points out a large abandoned wheat silo, which Cosco wants to convert into one of five high-end hotels; the company also envisions building a luxury shopping mall. The idea is to invest some 600 million euros to transform the sleepy town into a tourist hub, catering to cruise ships (some Chinese-owned) for which Piraeus is a stop. There is little to do in town currently, and passengers, if they disembark at all, make a beeline for the Acropolis 6.5 miles away. “The Chinese already have respect for ancient Greek culture,” Demenopoulos says. “But we still have a very small number of Chinese tourists compared to the thousands of Chinese millionaires.”

In 2017, not long after Cosco bought Piraeus, the European Union drew up a resolution to present to the United Nations condemning China’s crackdown on human-rights activists. The EU had presented such statements on multiple previous occasions. But this time, Greece blocked the resolution, and a Greek foreign ministry spokesman called it “unconstructive criticism of China.” That incident exposed a deepening divide among EU countries over how to deal with China—and stoked the fears of China hawks that countries would be willing to sacrifice principles for monetary gain.

This year, the stakes rose dramatically. In March, when President Xi landed in Rome for a state visit, Italy’s presidential guards lined up on horseback to greet him, as they do for the Pope. Later, tenor Andrea Bocelli serenaded Xi at a formal dinner. Italian companies signed deals with China worth $2.8 billion, and Italy agreed, in principle, to join the BRI, becoming the first member of the G7 group of major Western economies to sign on. Here, as in Piraeus, China’s maritime ambitions play a role: Italy is courting Chinese investment in four of its ports, including Trieste, a city whose direct-rail connections to Belgium and Germany represent some of Europe’s most valuable trade routes.

It was Xi’s splashy Italy visit that jolted EU officials into issuing their warning about China as a “systemic rival.” The EU plans to more rigorously monitor investments by state-owned companies like Cosco. It has begun rolling out guidelines to prevent countries from ceding control of strategic infrastructure or sensitive technology—an attempt to mirror the U.S. Treasury’s Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S., or CFIUS, which examines deals involving American companies. Closer examination of security threats and unfair competition “could severely affect China’s investment footprint in Europe,” concludes a recent report by the Rhodium Group and the Mercator Institute for China Studies in Berlin. Indeed, data on Chinese investment in Europe shows that its pace is already slowing.

Within Greece itself, divisions over foreign investment—including in Piraeus—run deep. Some critics have long griped that the government sold too low, even though Cosco was the highest bidder in an open process. Local officials have, for now, blocked Cosco’s hotel and mall plans, on the grounds that they would disturb archaeological sites.

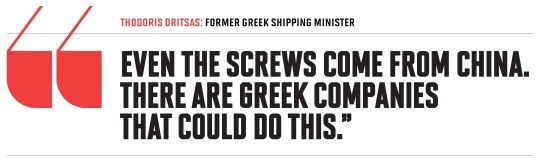

Some business leaders want the state to prevent Cosco from replacing Greek know-how with Chinese infrastructure. Piraeus’s cranes, for example, are supplied by ZPMC, a subsidiary of yet another Chinese state-owned entity. “Even the screws come from China,” says Thodoris Dritsas, a former Greek shipping minister. “There are Greek companies that could do this.” The dockworkers suspect Cosco has designs to replace their union members with freelance labor acquired through recruitment agencies.

At the national level, events are moving in Cosco’s favor. After campaigning against foreign takeovers, Tsipras’s Syriza Party was trounced in elections in early July. Voters wrung out from years of tax increases and belt-tightening voted in the New Democracy Party. Its leader, new Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, is a 51-year-old, Harvard-educated former venture capitalist who promises to lure big investors. In a conference about the BRI in Athens weeks before the election, the vice president of New Democracy, Adonis Georgiadis, said the party “welcomes Chinese companies to invest and grow in Greece.”

On a walk through Piraeus, worries about China’s influence seem dwarfed by the towers of containers on the dockside—bulky symbols of the port’s prosperity. Giorgos Gogos, general secretary of the local Dockworkers Union, says the era of strikes and protests is over—for now. That harmony could end if Cosco threatens union workers’ incomes. Still, after a decade of recession and pain, Piraeus’s dockworkers sense the chance for growth—or, at least, stability. “We are tired of struggling all the time,” Gogos says. “We need a period of peace.” For now, that desire for peace seems to outweigh national pride.

Additional reporting by Pavlos Kapantais

A version of this article appears in the August 2019 issue of Fortune with the headline “Boxed in at the Docks.”

More must-read stories from Fortune:

—The 2019 Fortune Global 500: See the full list

—It’s China’s world: China has now reached parity with the U.S. on the Global 500

—China’s biggest private sector company is betting its future on data

—How the maker of the world’s bestselling drug keeps prices sky-high

—Cloud gaming is big tech’s new street fight

Get up to speed on your morning commute with Fortune’s CEO Daily newsletter.

Credit: Source link

The post Boxed In at the Docks: How a Lifeline From China Changed Greece appeared first on WeeklyReviewer.

from WeeklyReviewer https://weeklyreviewer.com/boxed-in-at-the-docks-how-a-lifeline-from-china-changed-greece/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=boxed-in-at-the-docks-how-a-lifeline-from-china-changed-greece from WeeklyReviewer https://weeklyreviewer.tumblr.com/post/186465961862

0 notes

Text

Boxed In at the Docks: How a Lifeline From China Changed Greece

When Chinese shipping giant Cosco snapped up the historic port of Piraeus, it threw Greece an economic lifeline. Now the port’s success is reshaping the Greek political landscape—and generating choppy waters for China in Europe.

On a steamy night earlier this summer, about a thousand people poured into a public square in Athens to cheer on Greece’s leading left-wing politician, Alexis Tsipras. Tsipras was in the waning weeks of his term as Prime Minister—and trailing in a race against a pro-business opponent.

Leaping onto a makeshift stage in front of a banner reading “We have the power,” Tsipras shouted over the crowd. “This is a battle between two worlds, the elites against the many!” Then he took aim at foreign companies eyeing investment prospects in Greece, one of the countries hardest hit by Europe’s long financial crisis. “We have managed to get back to growth after eight straight years of recession,” Tsipras said. “Electricity, health, education, water, energy—they are not for sale!”

The promise to keep the country’s state-owned assets in Greek hands elicited a deafening roar. And yet Tsipras didn’t mention the most prized Greek asset of all: the port of Piraeus. Situated at the edge of Athens—a short sail from the Middle East and Africa—the port has been a strategic jewel for nearly 2,500 years, ever since the Athenians and Spartans defeated the Persian emperor in a nearby sea battle for Mediterranean supremacy. But as the crowd in the square knew, Tsipras’s own government had sold off Piraeus, years earlier, to a modern-day empire intent on expanding its own power: China.

When Chinese President Xi Jinping unveiled the ambitious vision he called the Belt and Road Initiative, or BRI, in 2013, he had commerce, not conquest, in mind. Xi announced that China would build a network of highways and rail lines (the “belt”) and sea routes (the “road”) across thousands of miles, linking Asia to Europe and Africa. The idea was to re-create the old Silk Road—the trade routes between East and West that were the foundations of the world’s first truly global commerce. The ultimate strategic goal: to expand and solidify a web of trading relationships that would cement China’s position as a dominant economic and political power for decades to come.

Piraeus has become a showcase display of the BRI in action—a project capable of transforming not just one port but perhaps an entire economy. It’s also an object lesson in the ways China’s biggest companies both execute and benefit from the BRI. The port has been majority-owned since 2016 (and operated since 2009) by China Cosco Shipping—a state-owned giant established nearly 60 years ago by Communist founding father Mao Zedong.

When Cosco stepped in, Piraeus “was a pretty backward container terminal that nobody took seriously,” says Olaf Merk, the ports and shipping expert at the International Transport Forum at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). “China saw an opportunity that was underdeveloped.” New management has brought dizzying change: This year, the port will handle five times as much cargo volume as it did in 2010, according to the Piraeus Port Authority. And it’s on track to become the biggest container port in the Mediterranean, perhaps as soon as this year, overtaking Valencia in Spain.

Cosco, meanwhile, has undergone its own rapid growth, thanks in large part to the BRI and to substantial Chinese government support. After several mergers with other transport companies, Cosco is now the third-biggest shipping company in the world by volume, with $43 billion in revenue—and significant stakes in other ports that ring Europe.

In recent years, China has trumpeted Piraeus as a model for what the BRI can achieve. And its impact is visible throughout Athens: in more jobs at the port, in Chinese-language advertisements for local real estate, and in plans to remake Piraeus as a tourist destination for the burgeoning Chinese upper classes.

But Piraeus’s revival also coincides with growing doubts in Europe about the strings attached to Chinese investment—as leaders question whether its sheer scale is a threat to Europe’s sovereignty, and perhaps even its security. Already, the political landscape in Greece has shifted in ways critics see as too friendly to China. Chinese naval vessels have docked at Piraeus—raising hackles at NATO, of which Greece is a member. This spring, as Xi toured the continent to stump for the BRI, European Union leaders issued a tough statement that for the first time called China a “systemic rival” whose political values—a centralized government with no tolerance for dissent, run by a leader with a lifelong grip on power—clash with Europe’s own.

The EU also called out Chinese state-owned enterprises like Cosco for having unfair advantages over the continent’s own private-sector companies. “The balance of challenges and opportunities presented by China has shifted,” the EU statement warned. Whether that balance should still tip toward cooperation is a debate now playing out on Piraeus’s docks.

When Westerners think about competition with China, the conversation often involves advanced technology—think artificial intelligence or 5G Internet. But the BRI underscores the importance of the infrastructure of trade itself: railways, roads, harbors. Ports may be the most vital link in that network. Roughly 90% of goods traded internationally makes its way around the world by sea. Control the shipping lanes and ports, and you wield great power over the global economy. “Xi thought, ‘What will my legacy be?’ ” says Nicolas Vernicos, a fourth-generation Greek shipowner and vice chairman of the Silk Road Chamber of International Commerce, a trade organization headquartered in China. “He decided to be the Marco Polo of the 21st century.”

If completed, the BRI will be one of history’s biggest infrastructure projects. Already Chinese companies are laying highways, operating ports, and creating railway networks in as many as 60 countries as varied as Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and Kazakhstan. Chinese government spending and subsidies keep the shovels moving. The Council on Foreign Relations estimates that China has spent about $200 billion on BRI projects so far; that investment could reach $1.2 trillion by 2027, according to Morgan Stanley. The result, Xi said in 2015, will bring “a real chorus comprising all countries along the route, not a solo for China.”

European voices make up only a small share of the chorus so far: The biggest BRI projects are underway in Asia and Africa. But outside of the BRI, Europe has seen Chinese investment rise quickly. With most EU economies still sluggish in the aftermath of the financial crisis, and heavy debt loads restraining government spending, Chinese companies have filled a void.��

Indeed, as trade tensions impair China’s ability to invest in the U.S., Europe now accounts for almost a quarter of China’s direct foreign investment—about $22 billion in the first half of 2018, according to law firm Baker McKenzie. State-owned ChemChina bought Swiss agribusiness giant Syngenta in 2017, for $43.1 billion. In 2016, China’s Midea spent $5.3 billion to buy German robotics manufacturer Kuka—which, among other things, keeps Volkswagen’s factories ticking. Technology player Huawei, which the Trump administration has branded as a national-security threat, maintains its largest logistics center outside China in Hungary, where it employs 2,000 people.

WHERE EMPIRES OVERLAP Athens is home to a community of some 10,000 Chinese expats. Photograph by Alfredo D’Amato—Panos Pictures for Fortune

A Chinese crossing the street with a trolley carrying article of clothing. Photograph by Alfredo D’Amato—Panos Pictures for Fortune

Cosco hopes to expand Piraeus as a tourism destination to compete with sites like the Acropolis for affluent Chinese visitors. Photograph by Alfredo D’Amato—Panos Pictures for Fortune

A Chinese man buying fruits at the local market. Photograph by Alfredo D’Amato—Panos Pictures for Fortune

“Money does not like a vacuum,” says Yanis Varoufakis, Greece’s left-wing former finance minister, who helped negotiate the country’s bailout with the International Monetary Fund and the EU in 2015. Varoufakis blames EU leaders for leaving companies vulnerable to takeovers. “European decision-makers [are] keeping investment at the slowest level in history and leaving the Chinese to come in as the only investors,” he says.

Cosco has quietly become one of the busiest of those investors. Even before the BRI was unveiled, it began acquiring stakes in numerous key ports, piecing together a network of terminals around Europe. (The company signs long-term concessions with local governments; Piraeus is the only European port where it owns outright a controlling stake.) Its holdings include 47.5% of the huge Euromax terminal in the Dutch city of Rotterdam; 100% of the container port in Zeebrugge, Belgium; and stakes in terminals in Valencia and Bilbao, Spain. In Israel, on Europe’s edge, it’s building ports in Haifa and Ashdod.

Cosco’s rise also shows how state-owned companies benefit when they subsume their strategy to the government’s grand plans. Growth and profitability are virtually assured—an advantage no U.S. or European company can match. “Operational losses of Cosco are compensated by state subsidies, and capital investments are made possible by generous credit lines,” explains Merk, the OECD analyst.

China’s government has given an astonishing $1.3 billion worth of tax subsidies to Cosco since 2010, according to shipping-research organization Alphaliner. Alphaliner estimates that Cosco’s 2018 profit of $251 million from shipping activities was attributable almost entirely to subsidies, which Cosco reported at $230 million. State-owned banks offer other largesse, often in the form of low-interest loans. In 2016, China’s Export-Import Bank provided Cosco with $18 billion in financing to buy ships and acquire companies. In 2017, Cosco got $26 billion in financing from the China Development Bank for BRI projects—work that Cosco now leverages to expand globally.

Cosco’s Chinese executive in Piraeus, Capt. Fu Cheng Qiu, declined multiple requests for interviews; Cosco officials elsewhere in Europe and China did not respond to interview requests. But publicly, the company’s officials aren’t shy about their plans for global growth. “Scale-up will still be the long-term trend for our industry,” Zhang Wei, executive director of Cosco’s port arm, said in April.

When you drive into Piraeus, five miles from downtown Athens, past auto-body repair shops and small cafés, there is no sense that you’re entering a flash point of controversy. Though some 450,000 people live in the town and its surrounding neighborhoods, Piraeus has the feel of a suburb that has seen better days. At lunchtime, the plastic tables at the café on the pier fill with dockworkers, smoking cigarettes and discussing their lives over $5 plates of sardines—offering a window into the tumultuous decade they have endured.

Giorgos Alevizopoulos, a burly man of 64 with a mustache and beard, says he began working in the port at 17, in 1972—when shipbuilding was Greece’s powerhouse industry. He ultimately became a welder, working on vessels under repair or maintenance on dry and floating docks where dozens of small companies operate on piecemeal jobs.

But by early this century, work in Piraeus had slowed to a crawl, as companies sought cheaper repairs in other nations or patronized more modern shipyards. Years of labor strife also reduced the port’s appeal. Alevizopoulos says he worked only about 50 days a year between 2005 and 2014. “My entire life changed, and my outlook on life changed. I even contemplated suicide,” he says. “Some days we just ate bread. If there was a question about what we eat that day, the answer was always whatever is cheapest.”

For years, the Greek government seemed content to run Piraeus largely as a commuter port for the ferryboats that take millions of locals and tourists to islands in the Aegean Sea. The shipyards and cargo port, meanwhile, deteriorated year by year. Laden with debt and bogged down by political schisms and bureaucracy, the government neglected the upgrades that could have retrofitted Piraeus to serve the rapidly growing large-container shipping industry. By 2010, yearly cargo traffic had fallen to 880,000 TEUs, or twenty-foot equivalent units, the standard measurement for container throughput—a paltry fraction of the capacity of Europe’s biggest ports.

In 2008, China made its move. Cosco, then known as the China Ocean Shipping Group, signed a concession with the Greek government to operate Piraeus’s container terminal for 35 years, in a deal worth about 1.2 billion euros ($1.4 billion) in rent and facility upgrades and another 2.7 billion euros in revenue sharing. The powerful dockworker unions, anxious at the prospect of foreign ownership, went on strike for six weeks. They hung a banner on Piraeus’s waterfront on the day the Chinese company took over that read “Cosco go home!” But with the global recession at its nadir, and few other options, the strikers soon returned to work.

Cosco quickly overhauled one of Piraeus’s piers and implemented a major upgrade of its loading cranes. That vastly expanded Piraeus’s capacity, turning the port almost overnight into an attractive destination for container vessels. Cosco also ran the port more efficiently. “Before, the employees were public servants,” says Vernicos, the shipowner. “They were working less than eight hours a day and fishing most of the time.”

Most important, Cosco now directs more of its own huge container-vessel traffic to Piraeus. As the ancient Greeks understood, Piraeus’s location makes it potentially invaluable. It is the closest major container terminal on the European mainland for ships emerging from the Suez Canal—and a gateway to a huge swath of southeastern Europe. “Before Cosco arrived, Chinese products had to go to Hamburg or Britain, and then they would go perhaps to the Balkans,” says Wu Hailong, owner of the Greece China Times, a newspaper catering to the 10,000 or so Chinese residents of Athens. “Now it saves about 10 days on the route.”

WELDING A BOND Cosco has achieved labor peace, for now, with Piraeus’s historically fractious dockworkers and shipbuilders. Photograph by Alfredo D’Amato—Panos Pictures for Fortune

Even as Piraeus got healthier, Greece labored under heavy austerity conditions imposed by its creditors. Its lenders demanded that the government make deep cuts to public spending—prompting hundreds of thousands of already-suffering Greeks to flood the streets in protest. Alexis Tsipras and Syriza won elections in 2015, campaigning on promises never to sell certain public assets. In the end, however, Greece had to do just that as a condition of a bailout by the EU and the IMF. Consider this: It sold its rail lines to Italy’s state-owned railway company for a tiny 43 million euros, less than some pro athletes earn in a year. Its natural-gas holdings were sold off to a private group; China State Grid, another state-owned company, bought a stake in Greece’s national utility. “Greece had choices, and it did not choose bankruptcy,” says Panagiotis Liargovas, an economist who headed the Greek Parliament’s budget office at the time.

In 2016, Greece agreed to sell 51% of Piraeus to Cosco, including 100% of its container terminal, for a bargain price of 368.5 million euros, plus 760 million euros in upgrades and revenue sharing. Piraeus became Chinese-owned, effectively in perpetuity. And in 2018, it processed 4.9 million TEUs, making it Europe’s sixth-largest cargo port.

Alevizopoulos, the welder, says his life has drastically changed for the better since then. He says he made nearly 20,000 euros last year—about four times as much as his earnings before the government sold the port. Even so, Greece’s economic ordeal has left its mark. “Psychologically, we have not recovered,” he says. “Like the rest of the people, we are still afraid.”

In August 2018, Greece finally exited the eight-year austerity program imposed by its creditors. Although the economy returned to growth in 2017, Greece’s GDP had shrunk an astonishing 45% between 2008 and 2016—the largest depression ever to strike a country in peacetime. It will take years more for outside lenders to feel secure about financing projects in Greece, says Yannis Stournaras, governor of the Bank of Greece, “so we hope for equity investment.” Such an influx is needed not just to boost the economy but also to literally rejuvenate Greece, the governor explains. Thousands of educated young people fled during the crash, and those who stayed have been reluctant to start families. “Only by producing good jobs will young couples produce more children,” Stournaras says.

Cosco says it is generating such jobs. While many Greeks worried that Chinese control would mean that imported workers would displace Athenians, only a handful of the port’s staff is Chinese, and those are managers, rarely seen amid the ships and stacks of containers. Cosco’s chairman, Xu Lirong, recently told Chinese media that the company has created 3,100 jobs for Greeks and added about $337 million a year to the Greek economy—a meaningful sum in a country with GDP of about $200 billion. The port’s revenues were about $151 million last year, up 19.2% from 2017, and Cosco says it is aiming to more than double the container volume Piraeus handles.

Boosters see Chinese money also bolstering other sectors that suffered during the dark years. Vaggelis Kteniadis, president of V2, one of Greece’s biggest real estate development companies, says he has had only five Greek buyers for his properties in Athens’s upscale seaside suburbs during the past 10 years. Kteniadis helped persuade Greece’s government to launch a “golden visa” program in 2013, offering foreigners resident status in exchange for investing 250,000 euros in Greek property.

Kteniadis estimates that Chinese buyers since then have snapped up more than 4,000 houses and apartments in Athens, about 450 from him alone, bought as second homes or short-term rental properties. Today, V2’s advertisements, in Chinese, are plastered across the baggage-claim area in Athens’s airport, offering home ownership as a rapid path to EU residency—an invaluable advantage for businesspeople. “The Chinese have saved Greek real estate,” says Kteniadis, who now has offices in four Chinese cities.

Chinese money could reshape the real estate of Piraeus itself. Guiding a reporter around the port one afternoon, Nektarios Demenopoulos, spokesman for the Piraeus Port Authority, points out a large abandoned wheat silo, which Cosco wants to convert into one of five high-end hotels; the company also envisions building a luxury shopping mall. The idea is to invest some 600 million euros to transform the sleepy town into a tourist hub, catering to cruise ships (some Chinese-owned) for which Piraeus is a stop. There is little to do in town currently, and passengers, if they disembark at all, make a beeline for the Acropolis 6.5 miles away. “The Chinese already have respect for ancient Greek culture,” Demenopoulos says. “But we still have a very small number of Chinese tourists compared to the thousands of Chinese millionaires.”

In 2017, not long after Cosco bought Piraeus, the European Union drew up a resolution to present to the United Nations condemning China’s crackdown on human-rights activists. The EU had presented such statements on multiple previous occasions. But this time, Greece blocked the resolution, and a Greek foreign ministry spokesman called it “unconstructive criticism of China.” That incident exposed a deepening divide among EU countries over how to deal with China—and stoked the fears of China hawks that countries would be willing to sacrifice principles for monetary gain.

This year, the stakes rose dramatically. In March, when President Xi landed in Rome for a state visit, Italy’s presidential guards lined up on horseback to greet him, as they do for the Pope. Later, tenor Andrea Bocelli serenaded Xi at a formal dinner. Italian companies signed deals with China worth $2.8 billion, and Italy agreed, in principle, to join the BRI, becoming the first member of the G7 group of major Western economies to sign on. Here, as in Piraeus, China’s maritime ambitions play a role: Italy is courting Chinese investment in four of its ports, including Trieste, a city whose direct-rail connections to Belgium and Germany represent some of Europe’s most valuable trade routes.

It was Xi’s splashy Italy visit that jolted EU officials into issuing their warning about China as a “systemic rival.” The EU plans to more rigorously monitor investments by state-owned companies like Cosco. It has begun rolling out guidelines to prevent countries from ceding control of strategic infrastructure or sensitive technology—an attempt to mirror the U.S. Treasury’s Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S., or CFIUS, which examines deals involving American companies. Closer examination of security threats and unfair competition “could severely affect China’s investment footprint in Europe,” concludes a recent report by the Rhodium Group and the Mercator Institute for China Studies in Berlin. Indeed, data on Chinese investment in Europe shows that its pace is already slowing.

Within Greece itself, divisions over foreign investment—including in Piraeus—run deep. Some critics have long griped that the government sold too low, even though Cosco was the highest bidder in an open process. Local officials have, for now, blocked Cosco’s hotel and mall plans, on the grounds that they would disturb archaeological sites.

Some business leaders want the state to prevent Cosco from replacing Greek know-how with Chinese infrastructure. Piraeus’s cranes, for example, are supplied by ZPMC, a subsidiary of yet another Chinese state-owned entity. “Even the screws come from China,” says Thodoris Dritsas, a former Greek shipping minister. “There are Greek companies that could do this.” The dockworkers suspect Cosco has designs to replace their union members with freelance labor acquired through recruitment agencies.