#Center for Cave Research at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

by Matti Friedman

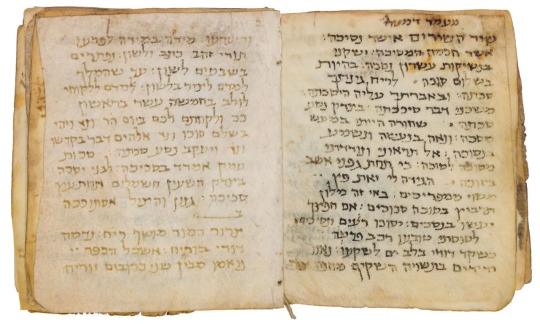

The little book may have been kept by a Jewish family in Bamiyan, the curator suggested, with different people adding new texts as the years passed. The hands of at least five scribes are evident in the pages. They were influenced by ideas and writing coming from both major Jewish centers of the time—Babylon, which is modern-day Iraq, and the Land of Israel, where Jewish sovereignty had been lost seven centuries before and whose people were now under Islamic rule.

The previously unknown poem shows the influence of a familiar biblical text, the erotic Song of Songs, according to Professor Shulamit Elizur of the Hebrew University, the member of the research team in charge of the poem’s analysis. But it also shows the impact of an esoteric Jewish book that wasn’t part of the Bible, known as the Apocalypse of Zerubbabel. This book is thought to have originated in the early 600s, when a brutal war between Byzantium and the Sasanian empire of Persia generated desperate messianic hopes among many Jews. Whoever wrote the poem in the Afghan prayer book had clearly read the Apocalypse, Elizur said—giving us a glimpse of a Jewish spiritual world both familiar and foreign to the coreligionists of the Bamiyan Jews in our own times, 1,300 years later. The previously unknown poem shows the influence of a familiar biblical text, the erotic Song of Songs, according to Professor Shulamit Elizur of the Hebrew University. (Museum of the Bible)

Chapters of the book’s journey from Afghanistan to Washington are unclear—some because they’re simply unknown even to the experts, and others because that’s the way the people in the murky manuscript market often prefer it.

When the book was discovered by the Hazara militiaman, according to Hepler, the tribesmen didn’t know exactly what it was but understood it was Jewish and assumed it was sacred. The local leader had it wrapped in cloth and preserved in a special box. At one point in the late 1990s, it seems to have been offered unsuccessfully for sale in Dallas, Texas, though it’s unclear if the book itself actually left Afghanistan at the time.

After the al-Qaeda attacks of 9/11 triggered the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, the book disappeared for about a decade. In 2012 it resurfaced in London, where it was photographed by the collector and dealer Lenny Wolfe.

Any story about Afghan manuscripts ends up leading to Wolfe, an Israeli born in Glasgow, Scotland. I went to see him at his office in Jerusalem, an Ottoman-era basement where the tables and couches are cluttered with ancient Greek flasks and Hebrew coins minted in the Jewish revolt against Rome in the 130s CE. It was Wolfe who helped facilitate the sale of the larger Afghan collection to Israel’s National Library. “The Afghan documents are fascinating,” he told me, “because they give us a window into Jewish life on the very edge of the Jewish world, on the border with China.”

When Wolfe encountered the little prayer book, he told me it had already been on the London market for several years without finding a buyer. In 2012, the year he photographed the book, he said it was offered to him at a price of $120,000 by two sellers, one Arab and the other Persian. But the Israeli institution he hoped would buy the book turned it down, he told me, so the sale never happened. Not long afterwards, according to his account, he heard that buyers representing the Green family had paid $2.5 million. When I asked what explained the difference in price, he answered, “greed,” and wouldn’t say more. (Hepler of the Museum of the Bible wouldn’t divulge the purchase price or the estimated value of the manuscript, but said Wolfe’s figure was “wrong.”)

The collection amassed by the Green family eventually became the Museum of the Bible, which opened in Washington in 2017. The museum has been sensitive to criticism related to the provenance of its artifacts since a scandal erupted involving thousands of antiquities that turned out to have been looted or improperly acquired in Iraq and elsewhere in the Middle East. The museum’s founder, Steve Green, has said he first began collecting as an enthusiast, not an expert, and was taken in by some of the dubious characters who populate the antiquities market. “I trusted the wrong people to guide me, and unwittingly dealt with unscrupulous dealers in those early years,” he said after a federal investigation. In March 2020 the museum agreed to repatriate 11,000 artifacts to Iraq and Egypt.

20 notes

·

View notes

Link

A rare coin from the Bar Kokhba revolt was discovered in the Qibya cave, 30 km northwest of Ramallah, the Coordination of Government Activities in the Territories announced Thursday. The coin is believed to have been minted between the third and fourth year of the Bar Kokhba revolt (136-134 CE).

One side of the coin shows a palm tree with seven fronds and two clusters of fruit, as well as the inscription “Shim[on].” The other side portrays vine leaves with three lobes and the inscription, “To the freedom of Jerusalem.”

Alongside the coin, the archeologists also found pottery fragments and glass vessels that can be dated to the same period. The coin was found during a study conducted by the Civil Administration of Judea and Samaria’s archeology unit, Bar- Ilan University and the University of Ariel during the “Southern Samaria Survey.” The survey is a project, brought to life in 2014, during which different teams of archeologists cooperate in surveying areas to unearth historical findings that have been left behind at various sites. “We estimate that there are many archeological artifacts that have not yet been discovered in the West Bank,” said Hanania Hezmi, the director of the Civil Administration’s archeology unit. “We are cooperating with all possible authorities in order to uncover important relics of Jewish history in the area.” Experts estimated that the items were brought to the cave by Jewish refugees who lived in the area until 135 BCE. During the Bar Kokhba revolt, they were forced to leave their homes and hide in the cave. The documentation of the artifacts found in the Qibya cave was carried out in cooperation with the Center for Cave Research at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

#jewish history#Center for Cave Research at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem#Bar Kokhba#jewish refugees

39 notes

·

View notes

Link

Israeli researchers discovered the world’s longest salt cave in Israel, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem reported Thursday. Malham Cave in the Dead Sea’s Mount Sedom at 10 kilometers long now bears this title.

An international expedition led by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HU)’s Cave Research Center (CRC), Israel Cave Explorers Club, and Bulgaria’s Sofia Speleo Club, along with 80 cavers from nine countries, recently completed mapping the cave. “Thirty years ago, when we surveyed Malham, we used tape measures and compasses,” explained Prof. Amos Frumkin, director of the CRC at HU’s Institute of Earth Sciences. “Now we have laser technology that beams measurements right to our iPhones.”

youtube

This technology helped the team to determine the cave’s record-breaking, double-digit length. Malham was initially discovered by the CRC back in the 1980’s. Later, tens of CRC expeditions surveyed Mount Sedom and found more than 100 different salt caves inside, the longest of which measured 5,685 meters. Subsequent carbon-14 tests dated the cave as 7,000 years old, give or take, and successive rainstorms created new passages for the cavers to explore. This new record was only discovered when the international expeditions returned to Malham in 2018 and 2019. These most recent expeditions were supported by the Bulgarian Federation of Speleology, the Ministry of Youth and Sports in Bulgaria, the European Federation of Speleology (FSE) and its sponsors Aventure Verticale, Korda's, Scurion and Bulgaria Air. Malham is the world’s first salt cave to reach a length in the double-digits. Currently, the survey team is processing final data from the new Malham Cave surveys to create an electronic map of the cave and to publish its findings.

Geologically speaking, salt caves are living things, according to an explanatory release by Hebrew U. They form mostly in desert regions with salt outcrops. What helps them form is water—even arid climates see the occasional rainstorm. When it does rain, water rushes down cracks in the surface, dissolving salt and creating semi-horizontal channels along the way. After all the rainwater drains out, these dried out “river beds” remain and salt caves are formed.

“The Malham Salt Cave is a river cave,” said Frumkin. “Water from a surface stream flowed underground and dissolved the salt, creating caves – a process that is still going on when there is heavy rain over Mount Sedom about once a year.”

Mount Sedom is named after a location mentioned in the Bible. he Book of Genesis describes how Lot’s wife became a pillar of salt after she looked back at Sodom.

“Mapping Malham Cave took hard work,” said Efraim Cohen, a member of HU’s research team. “We cavers worked 10-hour days underground, crawling through icy salt channels, narrowly avoiding salt stalactites and jaw-dropping salt crystals. Down there it felt like another planet.”

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Plans for Rehavia

Begun in 1922, the Rehavia neighborhood served as a “garden suburb” for Jewish families of Jerusalem who sought to escape the crowded conditions elsewhere in the city. The Palestine Land Development Corporation purchased the land used for building from the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate – which had acquired much land in the city during the 19th century and now found itself bankrupt in the 1920’s.

Rehavia was built in two stages during the British Mandatory period between 1925 and 1930.

The first stage, called Rehavia Aleph, was bordered by King George Street to the east, Ramban Street to the south, Ussishkin Street to the west, and Keren Kayemet Street to the north.

The second stage was completed in the early 1930s, between Jabotinsky Street, Ramban Street and Gaza Street.

The Results

Originally, Rehavia was meant to be a tolerant and liberal Jewish community with a modern outlook. Rehavia became an upper-class Ashkenazi Jewish neighborhood, home to professors and intellectuals. Almost all of Rehavia’s streets were named for poets and sages who lived during the Spanish Golden Age. The modern “International” houses integrated local elements, Middle Eastern or ancient. The homes were built in Jerusalem stone. The streets were lined by trees public gardens, playgrounds and even a tennis court. Don’t forget the vegetable gardens. Due to the arrival of olimim – refugees/emigrees from Nazi Germany – Rehavia earned its nickname “a Prussian island in an Oriental sea.”

Architect Richard Kaufmann designed Rehavia. He also planned many of Jerusalem’s neighborhoods, the plan provided for a central avenue – Ramban – crisscrossed by streets and Keren Kayemet, a curving street with many small shops.

Richard Kauffmann

This architect deserves a post of his own. His heritage helped create Zionist history. Richard Kauffmann was born in Germany. Arthur Ruppin met him in Germany and invited him to design new Jewish settlements in Palestine. Kauffmann immigrated to Palestine in 1920 and began his work as an architect. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s “International Style” influenced Kauffmann’s work. The International Style was nicknamed “Bauhaus” in Palestine and many tour guides still call it so. In contrast to the usual style of Jewish building at the beginning of the century. Then Jewish building was arranged around closed courtyards. In contrast, the houses of Rehavia faced outward, to the outside world.

His “Bauhaus” style was very popular in Palesting and became basis of the White City, as Tel Aviv’s International Style architecture became known.

He designed, almost alone, new rural villages, kibutzim and moshavim in the Jezreel Valley: most notably Ein Harod, Kfar Yehoshua, Degania Alef, Kfar Yehezkel and Nahalal.

Kauffmann designed some new Israeli cities: Afula, Herzliya, Rehavia. His neighborhood include Beit Hakerem, Talpiyot and Kiryat Moshe in Jerusalem, and Hadar HaCarmel, Neve Sha’anan, Bat Galim and Central Carmel in the city of Haifa.

Quasi Government Institutions

Jewish National Fund purchased some of the land from the Palestine Land Development Corporation (PLDC). On this land the JNF built the Gymnasia Rehavia high school on Keren Kayemet Street, Yeshurun Synagogue on King George Street, and the Jewish Agency building at the corner of King George and Keren Kayemet Street. These quasi government institutions were meant to replace the Temple in the Old City. All these buildings overlook the Old City.

Keren Kayemeth LeIsrael Road

Keren Kayemet Street

At the corner of Keren Kayemet Street there is a three-winged structure National Institutions Building with a large open courtyard, designed by Yochanan Rattner, This building housed the Jewish Agency, the Jewish National Fund and Keren Hayesod. Rattner gave it slanted walls, as in the walls of the Old City. Rattner, who was the first head of the Hagana’s National Command, also designed the Geography building in the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the Aeronautics building of the Technion in Haifa, the Kefar ha-Yarok Agricultural School, Bet Berl, Midreshet Ben Gurion, the Reali School in Haifa, and Beit Yad LeBanim in Beer Sheva.

Menachem Ussishkin, head of the Keren Kayemet (Jewish National Fund or KKL) decided that the street with the KKL headquarters should be changed from Shmuel Hanaggid Street to Keren Kayemet L’Yisrael Street. He transferred the name Shmuel Hanaggid Street to a nearby block.

National Institutions Building

Palestine’s second modern high school, after Gymnasia Herzliya in Tel Aviv, the Rehavia Gymnasium, was built in 1928 on Keren Kayemet Street.

Rehavia Gymnasium

Ramban Street

8 Ramban Street: The Greek Orthodox Church erected the windmill on Ramban Street some 150 years ago. When in operation, it ground wheat from the fields in the area into flour to feed Orthodox pilgrims visiting the Holy City.

Windmill on Ramban Street

26 Ramban Street: Gad Frumkin, the only Jewish Supreme Court justice to serve during the British Mandate, built the lovely dwelling on the corner of Ramban and Rehov Ibn Ezra in 1924. The sign “Havatzelet” (lily) over the door at #26 was a gesture to his father, who published a historic newspaper of that name for over 40 years.

Menachem Ussishkin

32 Ramban Street: Many years ago, I live on Ussishkin Street as a student, but this Ussishkin tale is new to me. As the story goes, Menachem Ussishkin was chairman of the JNF for 20 years. He was housed in a grand two-story villa near the Old City Walls, built by Swiss missionary banker who called it “Mahanaim” for the biblical verse:

“When Jacob saw them, he said, “This is the camp of God!” [Genesis 32:2]

So Ussishkin named that place Mahanaim (camp). In 1927, however, a severe earthquake damaged the British High Commissioner’s residence in Talpiot. The British commandeered Mahanaim and replaced Ussishkin with the commissioner. Ussishkin inscribed the name “Mahanaim” over the door of his new home at #32 Ramban. He also managed to change the cross street named for Yehuda Halevi (a Spaniard, and one of the greatest Jewish poets of all time) to Rehov Ussishkin in honor of his 70th birthday in 1933.

Rabbi Yehuda Halevi was not forgotten by city fathers. When Jerusalem was reunified in 1967, the steps from Misgav Ladach Street to the Western Wall Plaza were renamed in Rabbi Yehuda Halevi’s memory. Historically, Rabbi Halevi was fatally run over soon after he immigrated to the Holy Land, while kissing the ground near the Western Wall.

14 Ramban Street: Rehavia’s first home, completed in 1924, is near the top of Ramban Street#14. It was built by Eliezer Yellin. Eliezer was the son of David Yellin. David Yellin himself was a grandson to one of the founders of Nahalat Shiv’a over half a century earlier. It was Eliezer Yellin who named the neighborhood for Moses’ grandson, “Rehavia”.

“The sons of Moses: Gershom and Eliezer…and the sons of Eliezer were Rehavia the first. And Eliezer had no other sons; and the sons of Rehavia were very many” (I Chronicles 23:15–17).

Ibn Gabirol Street

14 Ibn Gabirol Street: The Ben-Zvi Institute of Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem was founded by Izhak Ben-Zvi in 1947, for the purpose of research relating to the history, communal life and culture of the Jewish communities under Islam and in other countries of the Middle East and Asia.

Balfour Street

3 Balfour Street: The Bauhaus building at No. 3 Balfour (at the corner Smolenskin streets) was designed by Richard Kaufmann for the wealthy Aghion family from Egypt. In 1939-40 the Aghions let the house to exiled King Peter of Yugoslavia. Today it is the official residence of Israel’s prime ministers.

Beit Aghion Photo: Haimohana

Alfasi Street – Jason’s Tomb

10 Alfasi Street: A burial tomb from Hasmonean times (2nd century BCE) uncovered in 1956, its Greek and Aramaic inscription includes an epitaph to the unknown Jason. Jason was either:

A High Priest in the Second Temple, instated in 175 BC by Antiochus Epiphanes after he ascended the throne of the Seleucid Empire and Jason offered to pay him for the appointment.

Possibly a naval commander, based on the charcoal drawing of two warships discovered in the cave.

The tomb was discovered on Alfasi Street in the Rehavia in 1956. I lived on Alfasi Street in 1965-66. I prefer the priestly lineage for Jason so that would make us relatives.

Ben Maimon Street

6 Ben Maimon Street: In the year of 1930, in Alexandria, Egypt, a Christian-Arab lawyer, Nasib Abkarius Bay married the daughter of a well known ultra-orthodox family from Jerusalem, Lea Tenenboim. So, he built a large house in Rehavia Neighborhood in Jerusalem, across the street from and Terra Sancta College and what would become the Aghion’s home (the Prime Minister’s official residence). The home was named “Villa Lea”. A year later, Lea sneaked out with a new lover to Egypt after spending a large sum of Abkarius`s money and left him broke and broken hearted. They divorced officially in 1945 and a year later Abkarius died poor and lonely. Later, the house was divided into three apartments. Through the years, Ethiopia Haile Selassie, David Hagoel, Eliezer Kaplan, Yosef Burg, Moshe Dayan and his daughter Yael Dayan have lived in Villa Lea.

Keren Hayesod Street

2 Keren Hayesod Street: The Società di San Paolo of Milan built Terra Sancta College on Keren Hayesod in 1926. Critics called it the “Opera Cardinal Ferrari.” The designer of the building was the famous, Italian architect Antonio Barluzzi.

Shmuel HaNagid Street

26 Shmuel HaNagid Street: Marie-Alphonse Ratisbonne, a French convert from Judaism established the Ratisbonne Monastery in Rehavia. Work on the building began in 1874 on a barren hill, now in the center of Jerusalem.

Ratisbonne Monastery

Rehavia Today

Today, offices replace families. Parking lots uprooted gardens. Now, new roads bisect Rehavia.

Rehavia, Jerusalem * The Plans for Rehavia Begun in 1922, the Rehavia neighborhood served as a "garden suburb" for Jewish families of Jerusalem who sought to escape the crowded conditions elsewhere in the city.

#Bauhaus#Gad Frumkin#International Style#Jerusalem#Menachem Ussishkin#Rehavia#Richard Kauffmann#Yochanan Rattner

1 note

·

View note

Text

How to make a book last for millennia

First discovered in 1947 by Bedouin shepherds looking for a lost sheep, the ancient Hebrew texts known as the Dead Sea Scrolls are some of the most well-preserved ancient written materials ever found. Now, a study by researchers at MIT and elsewhere elucidates a unique ancient technology for parchment making and provides new insights into possible methods to better preserve these precious historical documents.

The study focused on one scroll in particular, known as the Temple Scroll, among the roughly 900 full or partial scrolls found in the years since that first discovery. The scrolls were found in jars hidden in 11 caves on the steep hillsides just north of the Dead Sea, in the region around the ancient settlement of Qumran, which was destroyed by the Romans about 2,000 years ago.

The Temple Scroll is one of the largest (almost 25 feet long) and best-preserved of all the scrolls, even though its material is the thinnest of all of them (one-tenth of a millimeter, or roughly 1/250 of an inch thick). It also has the clearest, whitest writing surface of all the scrolls. These properties led Admir Masic, the Esther and Harold E. Edgerton Career Development Assistant Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and a Department of Materials Science and Engineering faculty fellow in archaeological materials, and his collaborators to wonder how the parchment was made.

The results of that study, carried out with former doctoral student Roman Schuetz (now at Israel’s Weizmann Institute of Science), MIT graduate student Janille Maragh, James Weaver from the Wyss Institute at Harvard University, and Ira Rabin from the Federal Institute of Materials Research and Testing and Hamburg University in Germany, were published today in the journal Science Advances. They found that the parchment was processed in an unusual way, using a mixture of salts found in evaporites — the material left from the evaporation of brines — but one that was different from the typical composition found on other parchments.

“The Temple Scroll is probably the most beautiful and best-preserved scroll,” Masic says. “We had the privilege of studying fragments from the Israeli museum in Jerusalem called the Shrine of the Book,” which was built specifically to house the Dead Sea Scrolls. One relatively large fragment from that scroll was the main subject of the new paper. The fragment, measuring about 2.5 centimeters (1 inch) across was investigated using a variety of specialized tools developed by researchers to map, in high resolution, the detailed chemical composition of relatively large objects under a microscope.

“We were able to perform large-area, submicron-scale, noninvasive characterization of the fragment,” Masic says — an integrated approach that he and Weaver have developed for the characterization of both biological and nonbiological materials. “These methods allow us to maintain the materials of interest under more environmentally friendly conditions, while we collect hundreds of thousands of different elemental and chemical spectra across the surface of the sample, mapping out its compositional variability in extreme detail,” Weaver says.

That fragment, which has escaped any treatment since its discovery that might have altered its properties, “allowed us to look deeply into its original composition, revealing the presence of some elements at completely unexpectedly high concentrations,” Masic says.

The elements they discovered included sulfur, sodium, and calcium in different proportions, spread across the surface of the parchment.

Parchment is made from animal skins that have had all hair and fatty residues removed by soaking them in a lime solution (from the Middle Ages onward) or through enzymatic and other treatments (in antiquity), scraping them clean, and then stretching them tight in a frame to dry. When dried, sometimes the surface was further prepared by rubbing with salts, as was apparently the case with the Temple Scroll.

The team has not yet been able to assess where the unusual combination of salts on the Temple Scroll’s surface came from, Masic says. But it’s clear that this unusual coating, on which the text was written, helped to give this parchment its unusually bright white surface, and perhaps contributed to its state of preservation, he says. And the coating’s elemental composition does not match that of the Dead Sea water itself, so it must have been from an evaporite deposit found somewhere else — whether nearby or far away, the researchers can’t yet say.

The unique composition of that surface layer demonstrates that the production process for that parchment was significantly different from that of other scrolls in the region, Masic says: “This work exemplifies exactly what my lab is trying to do — to use modern analytical tools to uncover secrets of the ancient world.”

Understanding the details of this ancient technology could help provide insights into the culture and society of that time and place, which played a central role in the history of both Judaism and Christianity. Among other things, an understanding of the parchment production and its chemistry could also help to identify forgeries of supposedly ancient writings.

According to Rabin, an expert in Dead Sea Scroll materials, “This study has far-reaching implications beyond the Dead Sea Scrolls. For example, it shows that at the dawn of parchment making in the Middle East, several techniques were in use, which is in stark contrast to the single technique used in the Middle Ages. The study also shows how to identify the initial treatments, thus providing historians and conservators with a new set of analytical tools for classification of the Dead Sea Scrolls and other ancient parchments.”

This information could indeed be crucial in guiding the development of new preservation strategies for these ancient manuscripts. Unfortunately, it appears that much of the damage seen in the scrolls today arose not from their 2,000-plus years in the caves, but from efforts to soften the scrolls in order to unroll and read them immediately after their initial discovery, Masic says.

Adding to these existing concerns, the new data now clearly demonstrate that these unique mineral coatings are also highly hygroscopic — they readily absorb any moisture in the air, and then might quickly begin to degrade the underlying material. These new results thus further emphasize the need to store the parchments in a controlled humidity environment at all times. “There could be an unanticipated sensitivity to even small-scale changes in humidity,” he says. “The point is that we now have evidence for the presence of salts that might accelerate their degradation. … These are aspects of preservation that must be taken into account.”

“For conservation issues and programs, this work is very important,” says Elisabetta Boaretto, director of the Kimmel Center for Archaeological Science at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, who was not associated with this work. She says, “It indicates that you have to know very well the document needing to be preserved, and the preservation has to be tailored to the document’s chemistry and its physical state.”

Boaretto adds that this team’s study of the unusual mineral layer on the parchment “is fundamental for future work in preservation, but most importantly to understand how these documents have been prepared in antiquity. This work certainly sets a standard for other researchers in this field.”

The work was partly supported by DFG, the German Research Foundation.

How to make a book last for millennia syndicated from https://osmowaterfilters.blogspot.com/

0 notes

Text

How to make a book last for millennia

First discovered in 1947 by Bedouin shepherds looking for a lost sheep, the ancient Hebrew texts known as the Dead Sea Scrolls are some of the most well-preserved ancient written materials ever found. Now, a study by researchers at MIT and elsewhere elucidates a unique ancient technology for parchment making and provides new insights into possible methods to better preserve these precious historical documents.

The study focused on one scroll in particular, known as the Temple Scroll, among the roughly 900 full or partial scrolls found in the years since that first discovery. The scrolls were found in jars hidden in 11 caves on the steep hillsides just north of the Dead Sea, in the region around the ancient settlement of Qumran, which was destroyed by the Romans about 2,000 years ago. It is thought that, to protect their religious and cultural heritage from the invaders, members of a sect called the Essenes hid their precious documents in the caves, often buried under a few feet of debris and bat guano to help foil looters.

The Temple Scroll is one of the largest (almost 25 feet long) and best-preserved of all the scrolls, even though its material is the thinnest of all of them (one-tenth of a millimeter, or roughly 1/250 of an inch thick). It also has the clearest, whitest writing surface of all the scrolls. These properties led Admir Masic, the Esther and Harold E. Edgerton Career Development Assistant Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and a Department of Materials Science and Engineering faculty fellow in archaeological materials, and his collaborators to wonder how the parchment was made.

The results of that study, carried out with former doctoral student Roman Schuetz (now at Israel’s Weizmann Institute of Science), MIT graduate student Janille Maragh, James Weaver from the Wyss Institute at Harvard University, and Ira Rabin from the Federal Institute of Materials Research and Testing and Hamburg University in Germany, were published today in the journal Science Advances. They found that the parchment was processed in an unusual way, using a mixture of salts found in evaporites — the material left from the evaporation of brines — but one that was different from the typical composition found on other parchments.

“The Temple Scroll is probably the most beautiful and best-preserved scroll,” Masic says. “We had the privilege of studying fragments from the Israeli museum in Jerusalem called the Shrine of the Book,” which was built specifically to house the Dead Sea Scrolls. One relatively large fragment from that scroll was the main subject of the new paper. The fragment, measuring about 2.5 centimeters (1 inch) across was investigated using a variety of specialized tools developed by researchers to map, in high resolution, the detailed chemical composition of relatively large objects under a microscope.

“We were able to perform large-area, submicron-scale, noninvasive characterization of the fragment,” Masic says — an integrated approach that he and Weaver have developed for the characterization of both biological and nonbiological materials. “These methods allow us to maintain the materials of interest under more environmentally friendly conditions, while we collect hundreds of thousands of different elemental and chemical spectra across the surface of the sample, mapping out its compositional variability in extreme detail,” Weaver says.

That fragment, which has escaped any treatment since its discovery that might have altered its properties, “allowed us to look deeply into its original composition, revealing the presence of some elements at completely unexpectedly high concentrations,” Masic says.

The elements they discovered included sulfur, sodium, and calcium in different proportions, spread across the surface of the parchment.

Parchment is made from animal skins that have had all hair and fatty residues removed by soaking them in a lime solution (from the Middle Ages onward) or through enzymatic and other treatments (in antiquity), scraping them clean, and then stretching them tight in a frame to dry. When dried, sometimes the surface was further prepared by rubbing with salts, as was apparently the case with the Temple Scroll.

The team has not yet been able to assess where the unusual combination of salts on the Temple Scroll’s surface came from, Masic says. But it’s clear that this unusual coating, on which the text was written, helped to give this parchment its unusually bright white surface, and perhaps contributed to its state of preservation, he says. And the coating’s elemental composition does not match that of the Dead Sea water itself, so it must have been from an evaporite deposit found somewhere else — whether nearby or far away, the researchers can’t yet say.

The unique composition of that surface layer demonstrates that the production process for that parchment was significantly different from that of other scrolls in the region, Masic says: “This work exemplifies exactly what my lab is trying to do — to use modern analytical tools to uncover secrets of the ancient world.”

Understanding the details of this ancient technology could help provide insights into the culture and society of that time and place, which played a central role in the history of both Judaism and Christianity. Among other things, an understanding of the parchment production and its chemistry could also help to identify forgeries of supposedly ancient writings.

According to Rabin, an expert in Dead Sea Scroll materials, “This study has far-reaching implications beyond the Dead Sea Scrolls. For example, it shows that at the dawn of parchment making in the Middle East, several techniques were in use, which is in stark contrast to the single technique used in the Middle Ages. The study also shows how to identify the initial treatments, thus providing historians and conservators with a new set of analytical tools for classification of the Dead Sea Scrolls and other ancient parchments.”

This information could indeed be crucial in guiding the development of new preservation strategies for these ancient manuscripts. Unfortunately, it appears that much of the damage seen in the scrolls today arose not from their 2,000-plus years in the caves, but from efforts to soften the scrolls in order to unroll and read them immediately after their initial discovery, Masic says.

Adding to these existing concerns, the new data now clearly demonstrate that these unique mineral coatings are also highly hygroscopic — they readily absorb any moisture in the air, and then might quickly begin to degrade the underlying material. These new results thus further emphasize the need to store the parchments in a controlled humidity environment at all times. “There could be an unanticipated sensitivity to even small-scale changes in humidity,” he says. “The point is that we now have evidence for the presence of salts that might accelerate their degradation. … These are aspects of preservation that must be taken into account.”

“For conservation issues and programs, this work is very important,” says Elisabetta Boaretto, director of the Kimmel Center for Archaeological Science at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, who was not associated with this work. She says, “It indicates that you have to know very well the document needing to be preserved, and the preservation has to be tailored to the document’s chemistry and its physical state.”

Boaretto adds that this team’s study of the unusual mineral layer on the parchment “is fundamental for future work in preservation, but most importantly to understand how these documents have been prepared in antiquity. This work certainly sets a standard for other researchers in this field.”

The work was partly supported by DFG, the German Research Foundation.

How to make a book last for millennia syndicated from https://osmowaterfilters.blogspot.com/

0 notes