#Cassilis Castle

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

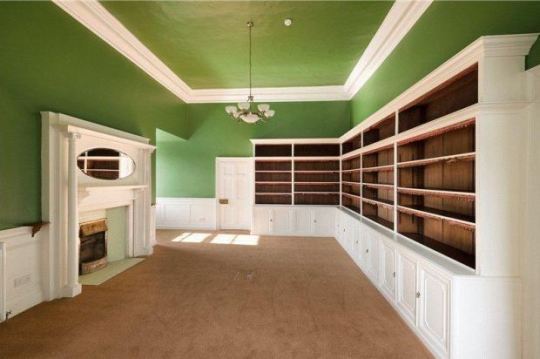

Cassillis Castle is located in Ayrshire, Scotland. The five-story castle was built in the 15th century on a high bank overlooking the Doon River. The property sits on 310 acres and has a gate lodge, a garden cottage, a stable block, a walled garden, and a courtyard. The interior boasts seven-bedroom suites, a ballroom, three reception rooms, a library, a secret staircase, a cinema, a state-of-the-art kitchen, six additional bedrooms, a spiral staircase, and a vaulted basement with a dungeon. The castle and lands were granted by charter to the Kennedy family after David Kennedy’s marriage to a local heiress. David Kennedy, the first Earl of Cassillis, took his title in 1502. The Kennedys owned the property until the 21st century. The castle was altered in the 17th century, and the square stair tower was added. In 1830, the 12th Earl of Cassillis added the two-story front and large extensions, which serve as one of the earliest examples of the Scottish Baronial style. The new owner, Australian entrepreneur Kate Armstrong, purchased the property in 2009 and began extensive renovations.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Castle Kennedy

Castle Kennedy is a ruined 17th-century tower house, about 3 miles (4.8 km) east of Stranraer, Dumfries and Galloway

The property belonged to the Kennedys from 1482; the castle was started in 1607, on the site of an earlier stronghold, by John Kennedy, 5th Earl of Cassilis. After a brief period in the hands of the Hamiltons of Bargany the property passed to the Dalrymples of Stair around 1677.

The castle was gutted by fire in 1716, and it was never restored.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

21st September 1513: Coronation of King James V of Scotland in Stirling

(The Honours of Scotland- the sceptre and sword were both gifts to James V’s father. Not my picture)

On this day in 1513, the young James V was crowned King of Scots in the chapel of Stirling Castle. Not yet eighteen months old, he had fallen heir to the throne a fortnight earlier after the death of his father James IV at the Battle of Flodden. After over twenty years of comparative stability under a popular adult monarch, Scotland now faced a long minority. While this was not an unusual occurrence in Scottish history, James V’s especially troubled minority would provide ample cause for the chronicler Adam Abell, writing twenty years later, to have recourse to that age-old complaint, “Wa is þe kinrik quar þe king is ane barne, ffor þan nowder pece nor iustice rang.” *

The future James V had been born at Linlithgow in April 1512, the fifth of King James IV’s legitimate children by his queen Margaret Tudor. None of the previous babies had survived infancy (though James IV had several living illegitimate children). Despite James IV’s hopeful observation that the new prince “gives promise of living to succeed” in a letter announcing the birth to his uncle the king of Denmark, and the English ambassador’s comment in 1513 that the Prince “is a right fair child, and a large of his age”, there was no way anyone could really be certain. His parents probably hoped for further children anyway, and by the end of August 1513, Margaret Tudor was again pregnant.

This time, however, other issues took precedence. Relations between Scotland and its neighbour England had recently deteriorated to the point where war seemed inevitable. Following on from James IV’s successful campaigns on the border in the 1490s, a Treaty of Perpetual Peace between England and Scotland had been signed in 1502. Within a decade, however, the fledgling peace was under threa. Political events on the continent had begun to impinge directly on the affairs of James IV’s small kingdom on the edges of Europe. James IV had generally enjoyed profitable relations with the papacy but now Pope Julius II had formed the Holy League with Spain, the Holy Roman Empire, Venice, and the Swiss. This was an alliance against Scotland’s ancient ally France. This placed the King of Scots in a bind and a bad situation was only made worse when the young Henry VIII of England (Queen Margaret’s younger brother), eager to make a name for himself on the European stage, was induced to join the Holy League. The king of England eventually led an invasion of France in summer 1513. When France appealed to Scotland for help, James IV was forced to choose between an old ally and the fragile truce. Deciding in France’s favour, he raised one of the largest armies Scotland had ever furnished and invaded the north of England in August 1513.**

The campaign initially went well for the Scots, who captured the Bishop of Durham’s great castle of Norham after a siege of only five days, and then took the smaller castles of Etal and Ford. But the Earl of Surrey had been appointed lieutenant of the north while the king of England was on the continent and hurried north from Yorkshire as soon as he heard of the invasion, arriving in Northumberland with his army in early September. James IV was willing to stand and fight, as he held a position of strategic advantage on top of Flodden Hill and his army had superior numbers and artillery. But Surrey outflanked him by marching his army to nearby Branxton hill on the morning of 9th September 1513, blocking the Scots’ retreat north. A pitched battle then ensued on the waterlogged fields in between the hills. The result was not only a defeat for the Scots, but one of the worst military catastrophes in Scottish history. The death toll as enormous, not least among the Scottish nobility and clergy: among the dead were the archbishop of St Andrews, the bishop of the Isles and the abbots of Kilwinning and Inchaffray; the earls of Argyll, Bothwell, Morton, Lennox, Cassilis, Caithness, Montrose, Erroll, Crawford, and Rothes; lords Elphinstone, Maxwell, Avondale, Borthwick, Ross, and Seton and many other lords, knights, and common soldiers. Worst of all, the king of Scots himself had been killed. The loss of so many men, and especially leading members of the political elite, was to have a lasting effect on Scotland’s political and cultural experience for decades to come.

(The memorial cross on Piper’s Hill overlooking the site of the Battle of Flodden. Source Wikimedia commons)

News of the appalling catastrophe spread gradually- disturbing rumours had reached Edinburgh by the next day, while confused stories continued to filter across Europe for some months. Shock, anguish, and denial seem to have been the immediate reactions back in Scotland, and for decades rumours would persist that James IV himself had not died, but had escaped somehow and might yet return. The news must have been particularly heavy for the young Queen Margaret, a widow at twenty-three and an English princess now mother to the new king of Scots, an infant who represented the hopes of an entire kingdom. As the full scale of the crisis became clear, the political community had to come to terms with the new situation swiftly, and ensure that the work of government, trade, justice, and domestic life carried on.

Not much is recorded of the government’s immediate reaction to the disaster, but by 19th of September 1513, a large number of lords and prelates had assembled at the castle of Stirling, a secure fortress which was further from the border than Linlithgow or Edinburgh and therefore a better seat of government in the face of possible English invasion. There the lords took measures to restore normality and reestablish authority; most importantly, the new king must be crowned as soon as possible. Despite his infancy, and the existence of adult male cousins just behind him in the line of succession who might have seemed more appealing as leaders during such a disturbed period, there is no evidence that the young James V’s claim to the throne was ever seriously questioned. In the immediate aftermath of Flodden, the political community rallied around the boy king and his mother, and it was arranged that his coronation would take place two days later on 21st September. In the meantime, the general council nominated over thirty nobles and churchmen to sit in daily council to advise on the government of the kingdom, with at least three spiritual and three temporal to remain in attendance always “as it lykis the queyn to command”.

The coronation went ahead as planned on Wednesday 21st September, “in the kirk of the castell of Striveling”. This would be the first occasion on which a coronation took place in Stirling, though the town was later to host the coronations of James V’s daughter Mary I (in the Chapel Royal) and grandson James VI (in the burgh kirk of the Holy Rude). It was a significant choice: while the coronations of the boy kings James II and James III had broken with the age-old tradition of inaugurating a King of Scots at Scone, James IV had restored this tradition upon his accession in 1488. However, the nobles who had placed the then fifteen year old James IV on the throne had come to power following a rebellion against the king’s father, James III, and Scone was probably chosen on that occasion to lend legitimacy to the new regime. By contrast, in 1513 the government’s priorities seem to have been security and speed in the face of any possible English invasions or public unrest. The infant king was therefore crowned in Stirling Castle’s chapel. It is usually assumed that this was the Chapel Royal, dedicated to St Mary the Virgin and St Michael, which had recently been erected to the status of a collegiate church and promoted as the chapel royal of the realm by James IV. However, due to reasons of space it is possible that the older chapel in the castle was used instead since, for all the attention lavished on it by James IV, the new Chapel Royal may have been too small to house large numbers of guests.

Not much is known about the coronation proceedings, but the surviving evidence gives the impression that it was a hastily planned affair. In the absence of an archbishop of St Andrews (the previous archbishop, James V’s older half-brother, having died at Flodden), the archbishop of Glasgow, James Beaton, was placed in charge of the proceedings “and all uther necessar provisioun”. Meanwhile, the music for the coronation may have been recycled from a previous Michaelmas celebration- it has been argued that Robert Carver’s beautiful “Missa Dum Sacrum Mysterium” was reworked for this purpose. The honours of Scotland- i.e. the crown jewels- were probably used in the ceremony, including the papal sword and sceptre which had been presented to the new king’s late father, though the toddler king may only have touched them from his position in the arms of an usher. But neither the glittering honours nor the soaring heights of the mass seem to have been enough to lift the spirits of the assembled guests, many of whom had lost fathers, husbands, brothers, and sons at Flodden. Not for nothing has this event become known in modern times as the “mourning coronation”.

youtube

(Robert Carver’s “Missa Dum Sacrum Mysterium”, thought to have been used at James V’s coronation in 1513)

Life had to go on however. Widows and orphans had to be provided for, and unrest and crime suppressed. Flodden was a military disaster, but it had not robbed Scotland of its entire political community. The wily James Beaton was soon made chancellor; Gavin Dunbar remained as clerk register; the ubiquitous Patrick Paniter- who had once been described as “the man who dooth all” about James IV- continued as secretary; and the aged yet dependable and experienced William Elphinstone still held the privy seal, while the government was soon pressing for him to be promoted to the vacant see of St Andrews. The chief alteration was in the official head of government. Soon after Flodden, Margaret Tudor had been recognised as tutrix testamentar and therefore regent for her young son, and she was exercising power in this capacity as early as 23rd September. Unlike Mary of Guise thirty years later, Margaret Tudor, though pregnant, was not yet in confinement at the time of her husband’s death and she was able to grasp the chance to become regent with both hands. Previous examples of Scottish queenship had permitted such regency, and Mary of Guelders at least had filled the role admirably (though she did not have a very good reputation in the early sixteenth century). While some among the Scottish political community might have preferred a man at the head of government during this crucial period, rather than a young English widow, and although the Earl of Arran and Lord Fleming had already tried persuading the young James V’s cousin and heir, the Duke of Albany, to return from France in order to lead Scotland during the minority, Margaret’s official rights to govern for her son would prevail, for the time being at least. It was a task which would have been daunting to even the most experienced statesman, but as yet it remained to be seen what she would make of it.

(King James V as an adult- born in 1512 and crowned in 1513, he would die at the age of thirty in 1542 and be succeeded in turn by another child monarch, his daughter Mary, Queen of Scots)

Notes and references beneath the cut.

*Basically “woe to the land where the king is a child”, a common adaptation of Ecclesiastes 10:16

**The breakdown in Anglo-Scottish relations in 1513 and the run-up to the Battle of Flodden is actually a lot more complex than this, however I was trying to be brief.

*** It’s quite interesting to compare James V’s coronation with that of his daughter Mary- there are some eerie similarities, but there are also some important differences, that I think shed more light on each individual situation.

*Selected* References:

“The Roit or Quheil of Tyme”, by Adam Abell, ed. S.M. Thorson

“The Historie of Scotland”, by John Leslie, translated into Scots by Father James Dalrymple

“The Historie and Cronicles of Scotland...” by Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie”, ed. Aeneas Mackay

“Acts of the Lords of Council in Public Affairs, 1501-1554″, ed. R.K. Hannay

“The Register of the Great Seal of Scotland”, volume III, ed. J. Balfour-Paul and J. Maitland Thomson

“The Letters of James IV”, calendered by R.K. Hannay

“The Minority of King James V, 1513-1528″, by W.K. Emond

“James IV”, by Norman McDougall

“Crown Imperial: Coronation Ritual and Regalia in the Reign of James V”, by Andrea Thomas, in “Sixteenth Century Scotland: Essays in Honour of Michael Lynch”, ed. Julian Goodare and Alastair A. MacDonald

“Glory and Honour: The Renaissance in Scotland”, by Andrea Thomas- this was also my source for the connection between Robert Carver’s Missa Dum Sacrum Mysterium and James V’s coronation. It is not a direct source- I believe the connection is explored in more death in “Musick Fyne” by Dr James Ross, but I was not able to access that book sadly.

#Scottish history#British history#James V#coronation#today in history#sixteenth century#James IV#Margaret Tudor#James Beaton Archbishop of Glasgow#Battle of Flodden#the Stewarts#kings and queens#Honours of Scotland#Robert Carver#Music#Stirling#Chapel Royal

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

September 9th 1513 was a sad day for us Scots, we lost our King and thousands more fellow countryman at The Battle of Flodden.

The Battle of Flodden Field was undoubtedly the most famous confrontation between the English and Scots ever fought on English soil. It took place eight miles to the north west of Wooler near the village of Branxton, Northumberland. The year before sought to renew the ‘auld alliance’ and assist the French by invading northern England, should England wage war on France, which they duly did.

Money and arms were sent to Scotland from France in the following months enabling King James to build up an army for a large scale invasion of England. On the 22nd of August a great Scottish army under King James IV crossed the border.

For the moment the earl of Surrey (who in King Henry ViII.’s absence was charged with the defence of the realm) had no organized force in the north of England, but James wasted much precious time among the border castles, and when Surrey appeared at Wooler, with an army equal in strength to his own.

Now I don't know how accurate this description is so don't shoot me, but it does have a feel of authenticity, it is from Robert White who describes the Scots army, in the Cambridge History of the Renaissance: “The principal leaders and men at arms were mounted on able horses; the Border prickers rode those of less size, but remarkably active. Those wore mail, chiefly of plate, from head to heel; that of the higher ranks being wrought and polished with great elegance, while the Borderers had armour of a very light description. All the others were on foot, and the burgesses of the towns wore what was called white armour, consisting of steel cap, gorget and mail brightly burnished, fitting gracefully to the body, and covering limbs and hands. The yeomen or peasantry had the sallat or iron cap, the hauberk or place jack, formed of thin flat pieces of iron quilted below leather or linen, which covered the legs and arms, and they had gloves likewise. The Highlanders were not so well defended by armour, though the chiefs were partly armed like their southern brethren, retaining, however, the eagle’s feather in the bonnet, and wearing, like their followers, the tartan and the belted plaid. Almost every soldier had a large shield or target for defence, and wore the white cross of Saint Andrew, either on his breast or some other prominent place. The offensive arms were the spear five yards in length, the long pike, the mace or mallet, two-handed and other swords, the dagger, the knife, the bow and sheaf of arrows; while the Danish axe, with a broad flat spike on the opposite side to the edge, was peculiar to the Islemen, and the studded targe to the Highlanders.”

The English commander promptly sent in a challenge to a pitched battle, at Millfield, an area of flat ground three miles north of Wooller, which the king, in spite of the advice of his most trusted counsellors, accepted.

On the 6th of September, however, he instead took up a strong position facing south, on Flodden Edge. Surrey was unhappy for the alleged breach of chivalry. This was at the end of the medieval period, I have pointed out before, battles, in the main, were fought to a code, breaches of which were rare,and so it was a second challenge to fight on Millfield Plain was sent. When Surrey’s herald arrived at the Scottish camp, James refused to meet him and instead sent word that he would not be dictated to by a ‘mere Earl’.

The English commander, at 70 years old was a veteran of many campaigns, then executed a daring and skilful march round the enemy’s flank, and on the 9th drew up for battle in rear of the hostile army.

It is evident that Surrey was confident of victory, for he placed his own army, not less than the enemy, in a position where defeat would involve utter ruin. On his appearance the Scots hastily changed front and took post on Branxton Hill’, facing north. The battle began around 4pm and Surrey’s archers and cannon soon gained the upper hand, the Scots, unable quietly to endure their losses, rushed to close quarters. Their left wing drove the English back, but their reserve corps restored the fight on the auld enemies side.

In all other parts of the field, save where James and Surrey were personally opposed, the English , gradually gained ground. The king’s corps was then attacked by Surrey in front, and by Sir Edward Stanley in flank. As the Scots were forced back, a part of the English reserve force closed upon the other flank, and finally charging in upon the rear of King James’s corps. Surrounded and attacked on all sides, this, the remnant of the invading army, was doomed. The circle of spearmen around the king grew less and less, and in the end James and a few of his nobles were alone left standing. Soon they too died, fighting to the last man.

Among the ten thousand Scottish dead were all the leading men in the kingdom of Scotland, and there was no family of importance that had not lost a member in this great disaster. The “King’s Stone,” said to mark the spot where James was killed, is at some distance from the actual battlefield.

Scottish dead included twelve earls, fifteen lords, many clan chiefs an archbishop and above all King James himself. It is said that every great family in Scotland mourned the loss of someone at the Battle Of Flodden. The dead were remembered in the famous Scottish pipe tune The Flooers o the Forest. Here is a partial list of those that died, those that know even just a wee bit of our history, through my posts, will recognise the names, if not of the actual knights themselves, but the families that have played such a part in our history.

Sir George Seton, 3rd Lord Seton Sir John Hay, 2nd Lord Hay of Yester George Douglas, Master of Angus Sir David Kennedy, Lord Kennedy and 1st Earl of Cassilis Sir William Graham, 1st Earl of Montrose Sir John Stewart, 2nd Earl of Atholl Sir William Leslie, 3rd Earl of Rothes Sir Archibald Campbell, 2d Earl of Argyll Patrick Buchanan, 16th Chief of Clan Buchanan Sir Robert Erskine, 4th Lord Erskine Sir John Somerville of Cambusnethan John Murray, Laird of Blackbarony Robert Colville, Laird of Hiltoun Sir Matthew Stewart, 2nd Earl of Lennox.

Add to the deaths, most of their sons were slain, what is extraordinary though, that of this wee snapshot, none of the lines ended, so there must have been plenty more offspring in Scotland!

You can read a more detailed account here https://www.britishbattles.com/anglo-scottish-war/battle-of-flodden/

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Culzean Castle is a castle overlooking the Firth of Clyde, near Maybole, Carrick, in South Ayrshire, on the west coast of Scotland.

It is the former home of the Marquess of Ailsa, the chief of Clan Kennedy, but is now owned by the National Trust for Scotland.

Culzean Castle was constructed as an L-plan castle by order of the 10th Earl of Cassilis.

He instructed the architect Robert Adam to rebuild a previous but more basic structure into a fine country house to be the seat of his earldom. The castle was built in stages between 1777 and 1792.

Culzean Castle, Scotland (by David Nicholls)

6K notes

·

View notes

Video

Culzean Castle by Allan Ogg Via Flickr: Formerly, the home of the Marquess of Ailsa, the chief of Clan Kennedy, the castle was designed by Robert Adam for the 10th Earl of Cassilis and was built between 1777 and 1792.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Tarbert Castle, Kyntire, Scotland

Tarbert Castle is located on the southern shore of East Loch Tarbert, at Tarbert, Argyll, Scotland, at the north end of Kintyre. Tarbert Castle was a strategic royal stronghold during the Middle Ages and one of three castles at Tarbert. The castle overlooks the harbour and although pre 14th century in construction, the tower dates back to 1494 and the visit of James IV to the Western Highlands. Wikipedia

Name: Sir Archibald Gillispie Campbell, 2nd. Earl of Argyll

Born: 6 May 1459 in Tarbert Castle, Argyll, Scotland

AKA: Sir Knight Archibald “Gillispie” of Argyll, Lord High Chancellor Scotland

Sir Archibald Gillispe Campbell – 2nd Earl of Argyll; ;Lord High Chancellor of Scotland

Married: 22 June 1479 in Renfrewshire, Scotland to Lady Elizabeth Stewart, of Lennox, and Countess of Argyll.

Died: 9 September 1513 at the Battle of Flodden Field, Branxton, Northumberlandshire, England

Buried: September 1513 in Scotland

Archibald was the eldest son of Colin Campbell, 1st Earl of Argyll and Isabel Stewart, daughter of John Stewart, 2nd Lord Lorne. He was made Master of the Royal Household of James IV of Scotland on 24 March 1495. After a crisis of law and order in the west of Scotland, Argyll was made governor of Tarbert Castle and Baillie of Knapdale, and this was followed by an appointment as Royal Lieutenant in the former Lordship of the Isles on 22 April 1500. Argyll eventually rose to the position of Lord High Chancellor of Scotland. His “clan” was rivalled only by Clan Gordon. The Earls of Argyll were hereditary Sheriffs of Lorne and Argyll. However, a draft record of the 1504 Parliament of Scotland records a move to request Argyll to hold his Sherriff Court at Perth, where the King and his council could more easily oversee proceedings, if the Earl was found at fault. The historian Norman Macdougall suggests this clause may have been provoked by Argyll’s kinship with Torquil MacLeod and MacLean of Duart. These western chiefs supported the suppressed Lordship of the Isles. The Earl of Argyll was killed at the Battle of Flodden on 9 September 1513, with the king and many others. He is buried at Kilmun Parish Church.

Archibald Gillespie Campbell, 2nd Earl of Argyll (died 9 September 1513) was a Scottish nobleman and politician who was killed at the Battle of Flodden. Biography: Archibald was the eldest son of Colin Campbell, 1st Earl of Argyll and Isabel Stewart, daughter of John Stewart, 2nd Lord Lorne. He was made Master of the Royal Household of James IV of Scotland on 24 March 1495. After a crisis of law and order in the west of Scotland, Argyll was made governor of Tarbert Castle and Baillie of Knapdale, and this was followed by an appointment as Royal Lieutenant in the former Lordship of the Isles on 22 April 1500. Argyll eventually rose to the position of Lord High Chancellor of Scotland. His “clan” was rivalled only by Clan Gordon. The Earls of Argyll were hereditary Sheriffs of Lorne and Argyll. However, a draft record of the 1504 Parliament of Scotland records a move to request Argyll to hold his Sherriff Court at Perth, where the King and his council could more easily oversee proceedings, if the Earl was found at fault. The historian Norman Macdougall suggests this clause may have been provoked by Argyll’s kinship with Torquil MacLeod and MacLean of Duart. These western chiefs supported the suppressed Lordship of the Isles. The Earl of Argyll was killed at the Battle of Flodden on 9 September 1513, with the king and many others. He is buried at Kilmun Parish Church.

Family: By his wife Elizabeth, a daughter of John Stewart, 1st Earl of Lennox, Argyll had issue: Colin Campbell Archibald Campbell of Skipness (d 1537 escaping from Edinburgh Castle), second husband of Janet Douglas, Lady Glamis Sir John Campbell of Calder (d.1546) ancestor of the Earls Cawdor Donald Campbell the Abbot of Coupar Angus Margaret Campbell, who married John Erskine, 5th Lord Erskine Isabel Campbell, married Gilbert Kennedy, 2nd Earl of Cassilis Janet Campbell, married John Stewart, 2nd Earl of Atholl Jean Campbell, married Sir John Lamont of that ilk, son Duncan Lamont Catherine Campbell, married Lachlan ‘Cattanach’ Maclean, 11th Chief of Duart, secondly to Archibald Campbell of Auchinbreck Marion Campbell, married Sir Robert Menzies of that ilk Elen Campbell, married Sir Gavin Kennedy of Blairquhan Mary Campbell

References: Year book of the American Clan Gregor Society. 1978. “Archibald Campbell, 2nd Earl of Argyll. He was the son of Colin Campbell, second Lord Campbell and 1st Earl of Argyll, … In addition to five daughters, the 2nd Earl of Argyll had four sons: 1. Colin Campbell — who became 3rd Earl of …” Macdougall, Norman, James IV, Tuckwell (1997), 107, citing Register of the Great Seal, vol. 2, no. 2240. Macdougall, Norman, James IV, Tuckwell (1997), 178, citing Register of the Privy Seal, vol. 1, nos. 413, 513, 520. MacDougall, Norman, James IV, Tuckwell (1997), 184-5, citing Acts of the Parliaments of Scotland, vol. 2, (1814), 241.

James Balfour Paul, Scots Peerage, vol i, pp 335-337 Peerage of Scotland Preceded by Colin Campbell Earl of Argyll 1493–1513 Succeeded by Colin Campbell Categories: Lord Chancellors of Scotland Earls of Argyll Deaths at the Battle of Flodden15th-century births 1513 deaths Court of James IV of Scotland

Scottish landowners

My Maternal 13th. Great Scottish Grandfather, Sir Archibald Gillispie Campbell, 2nd. Earl of Argyll Tarbert Castle, Kyntire, Scotland Tarbert Castle is located on the southern shore of East Loch Tarbert, at…

0 notes