#Carnegie Museum Catalog of Fossils

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Cephalopod Fossils from Lyme Regis, England

My position as a Research Volunteer in the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology (IP) allows me to delve into stories about the collection that I find interesting. One of my research assignments is to investigate the fossils from Lyme Regis, England. The Lyme Regis fossils are part of the 130,000 specimens purchased by Andrew Carnegie from the Baron de Bayet of Belgium in 1903. Some of the Bayet fossils are incorporated into the museum’s Dinosaurs in Their Time (DITT) in the Triassic, Jurassic, Cretaceous, and a special Lyme Regis case that showcases 13 invertebrate and vertebrate fossils.

The village of Lyme Regis is situated on the Dorset Coast, and as such, receives some of the worst weather associated with the English Channel. The Lyme Regis cliffs and beaches have been a fossil hunting graveyard for two hundred years, first made famous by resident Mary Anning (1799 – 1847). When she was just twelve years old she found a large skeleton of a marine reptile known as an Ichthyosaur (literally “fish lizard”). Ichthyosaurs were predators that fed on Jurassic fishes and ammonites. It’s easy to see how she developed a love of fossils after discovering such a magnificent creature as a child. For years, she amassed collections of plesiosaurs, pterosaurs, fish skeletons, and other marine fossils and sold them for a living to paleontologists worldwide. In DITT, there are two examples of Ichthyosaur specimens, a skull (CM 877) and a three-foot-long skeleton (CM 23822). Unfortunately, Mary Anning was not recognized during her life for her accomplishments, probably because she was not a trained paleontologist and she was female. After her death, the collections became widely known to the scientific community, bringing about a better understanding of the paleontology of the Dorset coast.

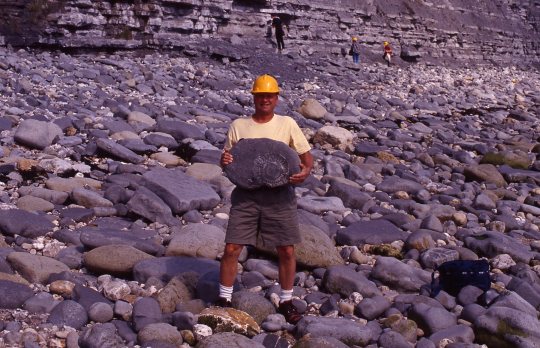

A fascinating piece of trivia about Lyme Regis is the filming of the 1980 movie, The French Lieutenant’s Women, which depicts the lead male actor, Jeremy Irons, using a simple rock hammer to extract a fossil ammonite from the cliff. If only it was that easy to collect from the 300-meter sheer cliff. My supervisor, Albert Kollar, collected fossils along the Lyme Regis beach in 1999. He opined “most fossils are eroded naturally because of the storm waves coming in from the English Channel that eat away at the rock each year, collapsing to the beach in broken blocks that eventually expose the fossils over time.”

My project was to research the Lyme Regis mollusks i.e., ammonites, nautiloids, and belemnites, update their identification, and review the climate aspects of the Jurassic sea that once covered this part of Europe approximately 199 to 190 million years ago. Paleontologists use marine fossils to interpret past paleoclimates and the paleoenvironments in which the animals once lived. The Jurassic is commonly considered as an interval of sustained warmth without any well-documented glacial deposits at the polar regions. The Lyme Regis fossils are preserved in very discrete layers of limestone strata often named “Lias” by European geologists. The terminology used today is early Jurassic Sinemurian Stage. The fossil mollusks are singular specimen’s that measure approximately 1 inch to 8 inches in diameter. The Carnegie of Natural History collection contains 16 invertebrate specimens from the genera Acanthoteuthis, Asteroceras, Eoderoceras, Liparoceras, Lytoceras, Microderoceras, Nautilus, Radstockiceras, and Xipheroceras.

All Bayet fossils were recorded in the Carnegie Museum Catalog of Fossils. The Cephalopod Catalog contains ammonite, nautiloid, and belemnoid fossils assigned by Bayet and includes details such as collection localities and stratigraphic horizon. Some Lyme Regis specimens are recognized by having two letters “BK” and a painted number, as seen on CM 40666. In 1975, a Swiss paleontologist, Dr. Felix Wiedenmayer, was on a research sabbatical to study fossil sponges at the Carnegie Museum, as well as an expert on Mesozoic ammonites from Europe. He reviewed many Mesozoic ammonites providing updated identification to genus and species, and stratigraphic horizon data, including some of the Lyme Regis ammonite fossils.

To complete the project, I created a virtual geology, paleontology, and exhibit folder in PowerPoint. This includes photographs of the specimens, a geologic map of Lyme Regis and the Dorset Coast, a Paleogeographic map, the distribution of genus and species in the collection, and references. The photographs in this study were taken by IP Research Associate/volunteer John Harper.

I have had a great experience at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History gaining knowledge about these fossil collections, stratigraphy, and geologic time. Now, I look forward to graduate school in part to study microfossils that lived in the seas during a climate “event” around 56 million years ago during the Paleogene Epoch. This event is called the “Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum” (PETM), and is so named because it demarcates the boundary between these two epochs of geologic time. It has been a pleasure looking at these exceptional cephalopods at the Carnegie Museum, and I look forward to any more potential collaborations in the future.

William Vincett is a research volunteer in the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology and a graduate student at the University of Delaware. Museum employees and volunteers are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Invertebrate Paleontology#Lyme Regis#Bayet fossils#Carnegie Museum Catalog of Fossils#Fossil#Fossils

132 notes

·

View notes

Link

Artist: Allan McCollum

Venue: Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, Miami

Exhibition Title: Allan McCollum: Works Since 1969

Date: March 26 – December 7, 2020

Curated By: Alex Gartenfeld and Stephanie Seidel

Click here to view slideshow

Full gallery of images, press release and link available after the jump.

Images:

Images courtesy of Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, Miami

Press Release:

The Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA Miami) presents the first U.S. museum retrospective for legendary American artist Allan McCollum (b. 1944), opening on March 26. Allan McCollum: Works Since 1969 traces the artist’s iconoclastic philosophy on the originality, value, and context of art. While McCollum’s contributions have been the focus of six major museum exhibitions in Europe and his work is included in more than 90 museum collections worldwide, this is the first museum exhibition in the U.S. to survey his 50-year career across a range of media, including painting, sculpture, photography, rarely seen early works and large-scale installations. Curated by ICA Miami Artistic Director Alex Gartenfeld and Associate Curator Stephanie Seidel, Works Since 1969 is on view at ICA Miami through July 19, 2020, and at the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum at Washington University in St. Louis from September 26 through January 4, 2021.

“For decades, Allan McCollum has explored how identity and community are created through collections of objects. In our fractious and digital age, his explorations of regional American culture have never been more timely,” said Alex Gartenfeld, ICA Miami’s Artistic Director. “McCollum’s work is profoundly influential on artists working on the role of the museum in society—yet has been underexplored to date. Our survey builds on ICA Miami’s history of providing the first major U.S. museum platform for artists whose work merits renewed attention and reveals insights about contemporary society and culture.”

Organized chronologically, Works Since 1969 brings together more than more than 20 series that blur the boundaries between mass-produced object and unique, exalted artifact. Some of the artist’s earliest major series, “Bleach Paintings” and “Constructed Paintings”—both begun in 1969—reflect McCollum’s interrogations of art history’s longstanding preoccupation with medium specificity. Not painted in a traditional sense, but instead made from materials widely available in supermarkets and hardware stores, McCollum considers the cultural conventions surrounding painting, fabricated through its context and social significance.

Critiques of originality and value carry through McCollum’s five decades of practice, demonstrated through a range of major series on view in the exhibition. These include his iconic “Surrogate Paintings” (1978– ) and “Plaster Surrogates” (1982– ), wooden wall-mounted reliefs and plaster casts shaped like framed pictures in monochromatic colors, which emphasize the conventions of framed images as a universal sign for anything meaningful and valuable.

Demonstrating the role of scale and repetition in his work, the exhibition additionally presents two of McCollum’s iconic sculptural series, “Perfect Vehicles” (1985– ) and “Over Ten Thousand Individual Works” (1987– ), which consider methods of collecting and the ways artworks accrue visibility, meaning, and value. McCollum also explores the notion of originality through photographic work, reflected in the “Perpetual Photos” (1982- ) series. For McCollum’s ongoing series, “The Shapes Project” (2005– ), he devised a simple numerical system to designate a unique shape for each person on the planet in the year 2050 (a total of 30 billion different shapes) using a simple home computer and Adobe Illustrator. Through this series, McCollum undermines the notion that art, if it is to be of any value, must be rare.

The centerpiece of the exhibition is McCollum’s rarely exhibited “regional projects,” works from the last three decades that explore how artifacts become charged with cultural meaning and how collections of objects and artifacts become agents for self-assurance and self-representation in regional communities. Works on view include The Dog from Pompei (1991), a cast of the famous form preserved as a natural mold in the volcanic ashes of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79; Lost Objects (1991– ), casts of fossilized dinosaur bones; and Natural Copies from the Coal Mines of Central Utah (1994), dinosaur tracks preserved in stone that are, themselves, copies; and THE EVENT: Petrified Lightning from Central Florida (1997) developed together with the International Lightning Research Center in Camp Blanding, Florida.

“By rethinking modes of artistic production and distribution as parts of larger economies of value, McCollum is one of the most influential American artists working today,” said Associate Curator Stephanie Seidel. “Over more than five decades his work has remained timely and effective at challenging aesthetic and material concerns, while critically reflecting on the museum context.”

Allan McCollum: Works Since 1969 is generously supported by the Knight Contemporary Art Fund at The Miami Foundation. Major support is provided by the National Endowment for the Arts, Jay Franke and David Herro, Isadore and Alexis Havenick, and Petzel Gallery. Additional support is provided by Eleanor Cayre, Lisa Roumell and Mark Rosenthal, Luciana Brito Galeria, Nancy Magoon, the Miami-Dade County Tourist Development Council, the Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Affairs, the Cultural Affairs Council, the Miami-Dade County Mayor and Board of County Commissioners

A richly illustrated exhibition catalog will accompany Works Since 1969, and will feature essays by the exhibition curators, and scholars Alex Kitnick and Jennifer Jane Marshall.

Allan McCollum (b. 1944, Los Angeles) has been making art for more than five decades. Survey exhibitions of his works have been held at, among others, the Musée d’art Moderne et Contemporain, Geneva (2006); Sprengel Museum, Hannover, Germany (1995–96); Serpentine Gallery, London (1990); Rooseum Center for Contemporary Art, Malmö, Sweden (1990); Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, The Netherlands (1989); and Portikus, Frankfurt, Germany (1988). He has produced public art projects in both the United States and Europe, and his works are held in over 90 art museum collections around the world. McCollum’s work has been included in numerous group exhibitions, including This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago (2012–13); The Pictures Generation: 1974–1984, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2009); The 1991 Carnegie International, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh (1991); Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (1975 and 1989); A Forest of Signs: Art in the Crisis of Representation, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (1989); and Aperto, Venice Biennale (1988).

Link: Allan McCollum at Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami

The post Allan McCollum at Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami first appeared on Contemporary Art Daily.

from Contemporary Art Daily https://bit.ly/2QUYct9

0 notes

Text

Bayet and Krantz: 16 Words (Part 1)

by Joann Wilson and Albert Kollar

In June of 1903, William Holland, Director of the Carnegie Museum, seized a rare chance to acquire one of the finest private collections in all of Europe. The purchase was made with sixteen words. Within in Holland’s Archives at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History Library, on onion paper so fragile that it appears to float, is a carbon copy of the telegram that influenced the early history of the Paleontology Department. Mysteriously, only one name appears on this fateful cable, and it is not a name that you would expect. The name is “Krantz,” Dr. Friedrich Krantz of Bonn, Germany.

Dr. Friedrich Krantz sitting in the conservatory, or wintergarten, at his villa in Germany, (date unknown). Permission of Ursula Müller-Krantz, Executive Director, Dr. F. Krantz.

In 1859, Friedrich Krantz was born into a family that operated a geological supply business. In 1888, Krantz graduated with a PhD in geology from the University of Erlangen. That same year, he joined “Dr. A Krantz,” the company founded by his uncle, Adam August Krantz. By 1891, Friedrich Krantz took charge and changed the company name to “Dr. F. Krantz, Rheinisches Mineraliaen Contor.” The company continues operations to this day out of headquarters in Bonn.

Exactly when Ernest Bayet of Brussels and Friedrich Krantz met is uncertain. But thanks to the letters and fossil lists that arrived with the Bayet collection, we know that they corresponded at least three times. The difficult task of translating these documents into English is being handled by volunteer Lucien Schoenmakers, a resident of the Netherlands. Schoenmakers’ translation work here and with other records is contributing critical information to the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology’s multiyear project to fully document the invertebrate portion of the Bayet Collection.

From the archive, we know that Krantz visited Bayet at least once. On July 7th, 1897, Krantz wrote, “I intend to come to Brussels towards the end of next week and will be honored to visit you, I can use the numbered list to give you the exact individual prices for all the objects displayed by me.”

In fact, Bayet may have selected Krantz to act as his agent for the sale because he was so familiar with it. Krantz sold many museum quality specimens to Bayet; many with distinctive, elegant labels.

Encrinus liliiformis Miller (CM 29840): a Triassic crinoid from Brunswick, Germany with Krantz label.

The sale of Baron Ernest Bayet’s fossil collection to the Carnegie Museum in 1903, made front page news in the New York Times, and other papers across the country. In a letter to Andrew Carnegie, thanking him for allocating $25,000 for the purchase, an enormous sum for that time, Holland wrote, “We are never likely to have another such chance, and you have done a most splendid thing in securing it [the Bayet Collection] for our Museum of Paleontology.” That most splendid thing transpired, over a century ago, with just sixteen words:

“Carnegie Museum buys collection. Will pay cash price fixed by Krantz. If satisfactory, telegraph answer yes.”

Cable sent from Pittsburgh to Brussels on June 9th or 10th, 1903 offering to buy Baron Ernest Bayet’s fossil collection. “Krantz” refers to Friedrich Krantz of Bonn, Germany, a business man and fossil dealer who acted as Bayet’s negotiating agent.

Part 2 of this series highlights spectacular Krantz specimens within the Bayet collection.

Many thanks for the generous contributions of Ursula Müller-Krantz, Executive Director of Dr. F Krantz Rheinisches Mineraliaen Contor GmbH & Co., Marie Corrado, Carnegie Museum of Natural History Library Manager and Kelsea Collins, Carnegie Museum Library Cataloger. Continued gratitude to volunteer Lucien Schoenmakers’ ongoing effort to translate archival Bayet documents. Joann Wilson is an Interpreter in the Education Department at Carnegie Museum of Natural History and Albert Kollar is Collections Manager for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Invertebrate Paleontology#Paleontology#Baron de Bayet#Natural History

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Student of the World:

Part 2: Stearns and Bayet

by Joann Wilson and Albert Kollar

“His [Frederick Stearns] love for that which was beautiful and useful, led him to collect a vast amount of material covering so many fields of human effort��”

Detroit Free Press, January 15, 1907

Fossils pass through many hands. Some hands hold discoveries, some buy and sell, others study and organize. Behind every fossil is a story and hopefully, for those in museum collections, a specimen label. With luck, the geology and paleontology of the label script is accurate. Beginning with the creation of the first color geological map by William Smith in 1815 and the subsequent organizing of the Geologic Time Scale in 1823, paleontologists worked to validate stratigraphy by collecting and describing new species from exposed strata in Europe and North America. It was not until the publication of Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species in 1859 that paleontological work shifted to include studying evolution as documented by fossil evidence.

Today we understand that many hands aided fossil discovery, often in anonymity. Thanks to technology and through a focus shift to the individuals behind the specimens, we can now provide a fuller picture of the past that acknowledges the roles of collectors, dealers, indigenous cultures, women, quarry workers, and all who aided in the pursuit of fossils.

In the basement of Carnegie Museum of Natural History, behind a set of gray steel doors in the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology, is an astonishing assembly of archival documents from the Bayet Collection. Andrew Carnegie made front page news in 1903 by purchasing an estimated 130,000 fossils from Ernest Bayet of Brussels. Along with the fossils, the museum also received hundreds of documents written primarily in French, German, and Italian. Most of it has remained untranslated, until now.

Thanks to volunteer Lucien Schoenmakers of the Netherlands, details of fossil trades and purchases from over 100 years ago provide links to narratives that have yet to be told. Join us as we start the journey. Our series, which began with an examination of correspondence between fossil collector Frederick Stearns and his client, Bayet, continues here with a deeper profile of Stearns.

Frederick Stearns, date unknown. Permission of the University of Michigan Stearns Collection.

Frederick Stearns of Detroit was a man not born into wealth, but with a passion for education, art, and science. His early life revolved around diligence, not fossils. Born in Lockport, New York in 1831, Stearns quit school at age 14 to find a job. Within a year, he found work as an apprentice to a pharmacist in Buffalo, New York. Of his early life, he later said, “one of my earliest memories is looking into the windows Dr. Merchant’s Gargling Oil Drug store and wondering at the mystery of the white squares of magnesia and the round balls of chalk.” Eventually, Stearns moved to another pharmacy, and became partner, but he was not convinced that Buffalo, New York was his ticket to success.

On a frosty New Year’s Day in 1855, Stearns, newly married and just 24 years of age, crossed the frozen Detroit River by foot to start anew. Of that period, he later said, “little money, fair credit, high hope.” He opened a retail pharmacy in Detroit. To reach customers, he made short trips to the surrounding area, leaving samples of his products. Over time, his business expanded to the manufacture of pharmaceuticals. In 1877, he made history by installing the first telegraph line in the city of Detroit. But despite the success, Stearns dreamed of the education lost to him when he left school at the age of 14. In 1887 at age 56, he turned the business over to his sons and he began to travel the world. Over the next twenty years, he collected many items, including fossils.

William Smith's 1815 Color Geological Map.

Stearns pursuits led him to Africa, Europe, and Asia. In the late 1800’s, a voyage to Japan required weeks of travel as compared to a current 14-hour flight from New York to Tokyo. In the early 1890’s, Stearns travelled to Japan twice for the purpose of studying mollusks and other marine life. In a book published in 1895 titled, “Catalog of the Marine Mollusks of Japan,” Stearns credits Japanese fisherman Morita Seto for assisting in the collection of over “1000 forms of marine life.”

But Stearns interest did not stop with mollusks. He also collected fossils, art, and musical instruments. His collection of musical instruments at the Stearns Collection of Musical Instruments at the University of Michigan, in Ann Arbor Michigan, is considered one of the finest in the world.

For a short time, Stearns also collected fossils. Between 1888-1889, he wrote two letters to Ernest Bayet about a trade deal. Stearns first letter offers a clue as to how they met. Both men appear to have known fossil dealer Lucien Stilwell of Deadwood, South Dakota. The trade between Stearns and Bayet did not go smoothly, but it does have a happy ending.

Stearns was a student of the world until the very end. In 1907, just days before he was scheduled to sail for Egypt, he became ill and died. At his passing, the Detroit Free Press wrote, “A remarkable phase of Mr. Stearns’s activities as a collector was their diversity… and all of this for the simple love of learning things that he might tell them to others without price.”

Many thanks to the generous contributions of Carol Stepanchuk, Outreach and Academic Projects at the U-M Stearns Collection of Musical Instruments Lieberthal-Rogers Center for Chinese Studies and Joseph Gascho, Associate Professor at the University of Michigan School of Music and Director of the Stearns Collection of Musical Instruments. Many thanks to volunteer Lucien Schoenmakers’ ongoing effort to translate archival Bayet documents written in French and German.

Joann Wilson is an Interpreter in the Education Department at Carnegie Museum of Natural History and Albert Kollar is Collections Manager for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Fossils#Invertebrate Paleontology#Paleontology#Frederick Stearns#Ernest Bayet

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Carnegie Geologists Win National Award

John Harper and Albert D. Kollar.

In the fall of 2018, Albert D. Kollar and John A. Harper (volunteer and research associate) of the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology in collaboration with the Pittsburgh Geological Society conducted a geology field trip titled: Geology of the Early Iron Industry in Fayette County, Pennsylvania. Back then, we had no idea this field guide would be recognized by the Geoscience Information Society with their GSIS Award 2019 for Best Guidebook (professional) at the Annual Meeting of the Geological Society of America (GSA). On September 23, 2019, Albert attended the Awards Luncheon in Phoenix, Arizona, to receive the GSIS Award.

Albert D. Kollar and Michael Noga representing Geoscience Information Society.

As stated by the GSIS committee chair, “The Geology of the Early Iron Industry in Fayette County, Pennsylvania is well-written and well-illustrated, with both professional and popular sections. I can see local geology teachers taking students on these trips to show a chapter in the development of an important early ore industry in the United States. With the aid of detailed road logs guidebook users can see and learn about the geology, industrial development, history, and fossils in Fayette County. Field Trip leaders can use the guidebook to expand on several topics, depending on the interests of their trip attendees. An additional benefit of the guidebook is its free availability online, so any traveler with an interest in the area can explore on their own. The Pittsburgh Geological Society has performed a great model for other local societies that are interested in spreading the benefits of their field trips to wider audiences.”

In receiving the award, Kollar opined that the guidebook has been recognized for the diverse geology of the region and the many historical sites that can be seen and visited respectively throughout southwestern Pennsylvania. These include, the geology of Chestnut Ridge, a Mississippian-age limestone quarry with abundant fossils and Laurel Caverns, the history of oil and gas exploration, the historic Wharton Charcoal Blast Furnace, the geology of natural gas storage, the country’s First Puddling Iron Furnace, and the birth place of both coke magnate Henry Clay Frick and Old Overholt Straight Rye Whiskey, West Overton, Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania.

Another feature of the guidebook is its dedication to Dr. Norman L. Samways, retired metallurgist, geology enthusiast, and good friend who spent many years as a volunteer with the Invertebrate Paleontology Section of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Sam, as we called him, passed away in February 2018. His contribution came about when he was instrumental in the research and writing of the Geology and History of Ironmaking in Western Pennsylvania, with his co-authors John A. Harper, Albert D. Kollar, and David J. Vater, published as PAlS Publication 16, 2014. Moreover, Sam was solely responsible for a new historical marker, AMERICA’S FIRST PUDDLING FURANCE along PA 51, dedicated on September 10, 2017 by the Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission and the Fayette County Historical Society. David Vater contributed to the guidebook’s content by drawing a schematic diagram of a typical puddling iron furnace, which is greatly appreciated. Key fossils and iron ores of the section’s collection are referenced as well. The cataloged fossils cited in peer review journals authored by section staff and research associates includes those on the trilobites by Brezinski (1984, 2008, and 2009), Bensen (1934) and Carter, Kollar and Brezinski (2008) for brachiopods, and Rollins and Brezinski (1988) for crinoid-platyceratid (snail) co-evolution.

In recent years, the section has run highly successful regional field trips about various geology and paleontology topics based on the museum collections, collaborations with the Pittsburgh Geology Society, the Geological Society of America, Osher Institute of the University of Pittsburgh, Nine-Mile Run Watershed, Allegheny County Parks, Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy, Montour Trail, Carnegie Discovers, and the section’s own PAlS geology and fossil program. A future field trip is being planned to assess the dimension stones that built the Carnegie Museum and noted architectural building stones of Oakland.

Albert D. Kollar is the Collection Manager in the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bayet’s Bounty: The Invertebrates That Time Forgot

Albert Kollar, Collections Manager for the Carnegie Museum of Natural History Section of Invertebrate Paleontology, is on a mission to re-examine the Bayet Collection, a collection of 130,000 invertebrate and vertebrate fossils brought to the Carnegie more than 100 years ago. Albert is re-examining the invertebrate portion of the Bayet (pronounced “Bye-aye”), which as it turns out, is 99.9% of the collection.

The story starts with a last-minute trip that began on July 8, 1903 by Carnegie Director William Holland, who had received word of a world-class fossil collection that had been put up for sale in Europe by the Baron de Bayet, first secretary to King Leopold II of Belgium. Holland immediately booked passage to Europe on the steamer “New York” to complete the deal. At stake were 130,000 invertebrates, combined with a small number of vertebrate fossils (several on display in the Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibition), sought by museums throughout Europe, Great Britain and the United States. This collection became the largest addition to the department of paleontology at the Carnegie Institute, since the discovery of the dinosaur Diplodocus carnegii, at Sheep Creek, Wyoming in 1899.

Mr. Carnegie personally wrote a check for $25,000 for the project, a sum so large it exceeded the entire 1903 budget for all art and natural history acquisitions combined. Eventually, Mr. Holland negotiated a price of just under $21,000 with the Baron de Bayet for the entire collection. Another $2,300 was spent to pack, insure and transport everything back to Pittsburgh. Twenty men and women worked for three weeks to meticulously wrap each fossil in cotton, batting, or straw and by September 1903, two hundred and fifty-nine crates arrived safely in Pittsburgh. Storage of the crates was an issue, since the Carnegie Museum building would not be completed until 1907; so Mr. Holland rented space in a warehouse on 3rd Street in Pittsburgh for storage of 210 of the 259 crates.

This decision, however, almost destroyed the collection when a fire broke out on the upper floors of the 3rd Street warehouse. On December 30, 1903, Mr. Holland wrote, “Yesterday brought with it a fire in which it appeared as if the Bayet collection, the acquisition of which we had so prided ourselves, was destined to go up in smoke.” Fortunately, the Pittsburgh Fire Department contained the fire to the upper floors and the Bayet collection, stored on the lower floor, and meticulously wrapped and crated, survived with minimal damage. The crates returned to the Carnegie Institute to dry out.

In early 1904, William Holland hired Dr. Percy Raymond, a graduate of Yale University, to be the first curator of Invertebrate Paleontology. His primary directive was to catalog and organize the Invertebrate portion of the Bayet collection. Today, over 100 years later, Albert Kollar with the help of Pitt Geology student E. Kevin Love, is undertaking a multi-year project to translate Percy Raymond’s beautifully hand-written catalogs and to migrate all 130,000 specimens into a new database.

Pictured below is (BH1) the very first Bayet specimen cataloged by Percy Raymond. BH1 is an exquisite 510-million-year-old, CM 1828 Paradoxides spinosus, a 17.17 cm or 7” long trilobite from Skreje, Bohemia – or the Czech Republic of today.

Albert’s goal in revisiting the Bayet collection is to better understand the great history of the how, why and where of fossils collected in the late 19th century, especially in Europe the birthplace of paleontology and geology. “This project will give us insight into why certain Bayet fossils were recovered from classic European fossil localities, many of which are designated stratotype (significant geologic time reference) regions. These fossils and localities have been used to document the validity of evolution, extinction, and the Geologic Time Scale over the last 100 years. With an improved database, we hope to better appreciate the scientific value of the entire collection and create new statistical measures for future research and education.”

When asked if he expected any surprises as we go forward, Albert smiled, “Not until all the data has been analyzed will we have an opportunity to review the collection’s full scientific worth.”

Check back in a few months, Bayet’s invertebrates may have a few secrets yet to share.

Many thanks to Carnegie Museum Library Manager, Xianghua Sun for help researching this post.

Joann Wilson is an Interpreter in the Education department at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Bayet#Invertebrate Paleontology#Fossils#Stratotype#Paleontology#Geology#William Holland#Andrew Carnegie#Pittsburgh

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Clues

By Amy Henrici

Collection Managers often solve fossil mysteries, and sometimes we have only a few clues to assist us. A recent mystery involved some rib fragments prepared by PaleoLab volunteers. Individual packages containing rib fragments found in an old cardboard box stashed in a Vertebrate Paleontology storage room proved to be perfect for PaleoLab volunteers to hone their preparation skills.

My task as Collection Manager is to catalog and integrate these ribs into the fossil mammal collection. Fortunately, most of the rib packages contained field labels, which are used to record information when the specimen is collected. My first clue came from the Description category of a field label with one of the rib packages, and it indicated that the rib connected with a block (which consists of fossil and rock). Because there are no blocks of unprepared fossil mammals in storage, I had to assume that this block had been prepared and the specimen was cataloged. The field label lacked a catalog number (Department No. on the label) and any locality information, which would normally assist in locating the rest of the specimen.

This field label must have been printed for an expedition to Brazil, and the left overs were used by all museum expeditions until they ran out.

The only clue that I had to link the rib to a cataloged specimen in the Section’s computerized database was the block number (Blk. 11/1931), which are entered in the field number category of the database. A search of the database retrieved two specimens with this field number, CM 6425 and CM 36355. Both were brontotheres, formerly known as titanotheres, which are large, extinct rhinoceros-like herbivores. I located the specimens in the collections, and both included incomplete ribs. The field label shown here mentioned that the rib made contact with a “...portion in block indicated by letter D”. Amazingly, I found the letter D written on the broken end of a rib cataloged as CM 6425, and the rib fragment associated with the field label connects to it. I was able to fit all of the rib pieces prepared in PaleoLab onto other ribs cataloged as CM 6425.

The rib piece held in the left hand fits onto a piece stored in this drawer. Both have the letter D written on them at the point where they join. (Photograph taken by Norm Wuerthele)

Archive image showing the skeleton of the brontothere, Brontops dispar, CM 767, which can be seen on exhibit in Cenozoic Hall.

Amy Henrici is the Collection Manager for Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences of working at the museum.

131 notes

·

View notes