#California anti-miscegenation laws

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Dear toontown justice department.

I have come asking if there is a law against human x toon relationships.

You see, during a bar visit, I have become best friends with a toon. A cute and smug fox girl. We kept it casual for years with me thinking it was a completely platonic relationship. However, recently, she has been sending me love related gag gifts and has been trying to get me to go on a date with her. I really enjoy her company, so I wanted to know if I had to let her down easy due to a law not allowing us to date like how there used to be a law like that for the LGBTQ+ community.

- sincerely

A confused cartoonist

Ooc: Quick note, this blog takes place in 1947 (Don't ask how someone in the 1940's having a blog works) and shall be answered accordingly. As a side note, I headcanon that Toon Town is more LGBTQ+ friendly during that time period. Case in point: Looney Tunes crossdressing.

Bic: That varies from state to state. You'll have to ask your local judge what the policy is on interracial marriage. Yes, Toons are counted legally as a race rather than a separate species, despite many claiming otherwise. Right now in California, there is currently an ongoing case to try and repeal anti-miscegenation laws.

It's my personal opinion, though, that interracial marriage should be legal for... personal reasons.

Ooc: BTW here's a chart of which states legalized interracial marriage in which time periods from Wikipedia

California legalized Interracial marriage in 1948, one year after Who Framed Roger Rabbit takes place, as a result of Perez v. Sharp. Yay for knowledge!

#unreality#who framed roger rabbit#toontown#toontown justice department#inserted a history lesson#also yes I am implying my character has a crush on a toon

1 note

·

View note

Photo

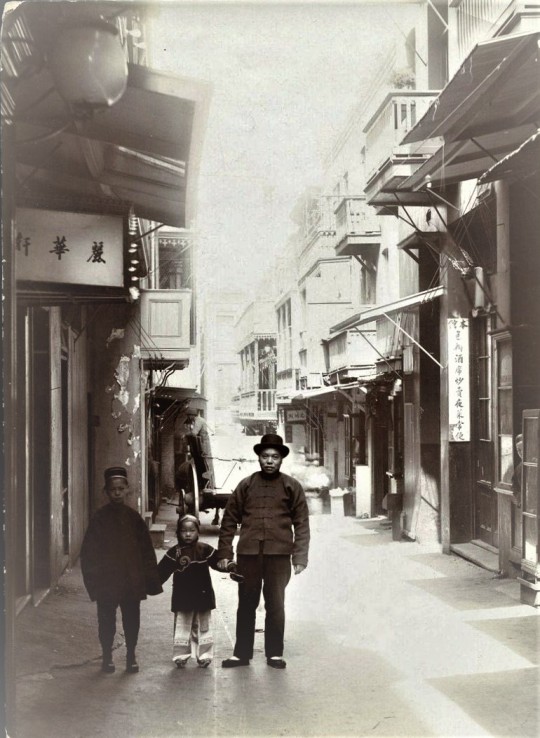

Chinese merchant with his two children in Ross Alley of pre-1906 San Francisco Chinatown, c. 1902. Photograph attributed to Charles Weidner.

Two Fathers of Old Chinatown

In the late nineteenth century, a host of photographers flocked to San Francisco Chinatown to capture images of the pre -1906 neighborhood and particularly its children. Photos by Arnold Genthe of Chinatown’s children proved particularly popular, and many images by Genthe and others were sold to tourist postcard publishers.

Linking two separate images of the same family from Chinatown’s pre-1906 photographic record represents an extraordinary find. However, this Father’s Day brings a second pair of photographs of an individual working in a very different sector of old Chinatown’s economy than the father seen in the first set of photos.

The Merchant

The image of a Chinese father with his son and daughter in Ross Alley remains striking today. From the better tailoring of his jacket and style of hat, the father appears to be a merchant. He looks confidently into the camera lens with a half-smile, gripping his daughter’s left hand through the long sleeve of her tunic. The girl is flanked by his son who also looks directly at the photographer. A horse-drawn wagon can be seen behind the trio, making deliveries to the businesses in the alley in much the same manner as occurs in Ross Alley of this century. The image of a Chinese father and his children became well-known as a result of numerous printings as a postcard.

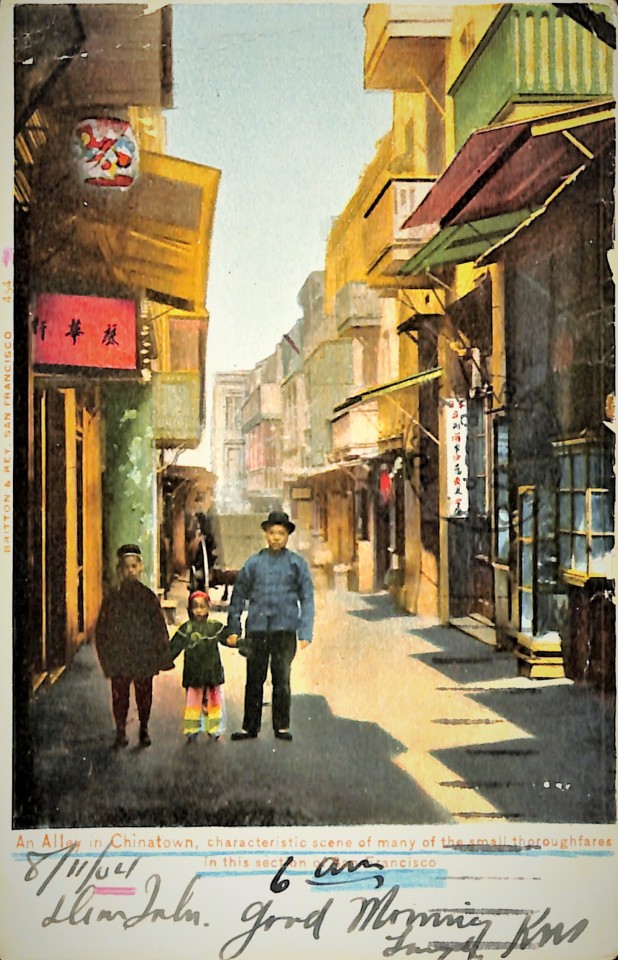

“An Alley in Chinatown, characteristic scene of many of the small thoroughfares in this section of San Francisco” c. 1902. Photograph attributed to a negative by Charles Weidner, postcard published by Britton & Rey, San Francisco (from the collection of Wong Yuen-Ming).

This Father’s Day, however, brings a fortuitous discovery in the form of a second photo of the same Chinese merchant and his children in a different Chinatown location (and perhaps by a different photographer).

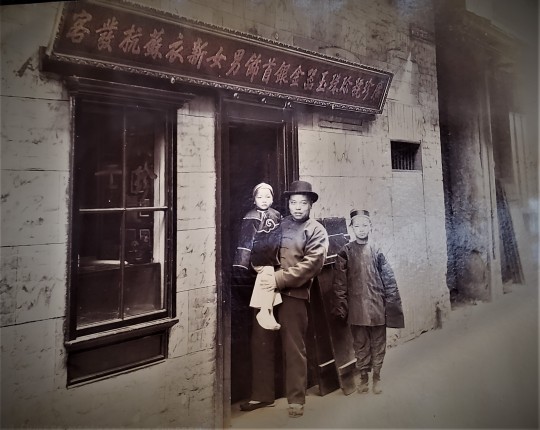

Chinese merchant and his children. Photographer unknown (from the Cooper Chow collection at the Chinese Historical Society of America).

In the above image, the same trio of father, daughter and son are wearing the same clothes and posing in front of what is probably the father’s business premises. Prominent advertising signage appears above the doorway to the business which reads from right to left as follows: 廣珍號珍珠玉器金銀首飾男女新衣蘇杭發客 or roughly “Guangzhen Pearl Jade Gold and Silver Jewelry Men's and Women's New Clothes Suzhou and Hangzhou” (pinyin: “Guǎng zhēn hào zhēnzhū yùqì jīnyín shǒushì nánnǚ xīn yī sūhángfā kè “; canto: “Gwong Zun ho sunjiu yok hay gam ngan sau sik nam neuih sun yee so hong faat haak”).

The barely discernible calligraphy on the upper-right pane of the store window frame bears the probable business name, 廣珍 (“Gwong Zun”).

Magnification of the window reveals at several photographs that can be seen through the window. At least four framed photos are visible on a wall behind a desk. On the most discernible of the photos, a figure appears to be seated and holding a fan – a pose commonly used by Chinese subjects in the studio portraiture of the late 19th century. The figure could be an ancestor or even the merchant’s wife, as photos became essential evidence to overcome the hurdles to the effective denial of entry to the US by Chinese females after the enactment of the Page Act of 1875 which purported to bar the immigration of prostitutes.

A couple of wooden shutters appear behind the merchant and his son. The panels would have been used to cover the window as a security measure. A similar set of shutters also appear at the far right of the photo frame, indicating the merchant shared this alleyway or street with other businesses. Unfortunately, the signage (appearing in the upper right-hand corner of the frame), for what appears to be a street number or street name is illegible.

Outside of his store, the merchant shows more of a smile as he looks directly at the camera lens, perhaps more familiar with the photographer. Even his son has started to show the beginning traces of a smile. This implies that the photographer either followed the trio to father’s place of business from Ross Alley or encountered the merchant and his offspring for another shot.

The Highbinder

The serious study of the role of illegal business enterprises played in the micro-economy of segregated and marginalized communities such as old San Francisco Chinatown remains to be written. However, the fact that gambling establishments played an out-sized role in the ghetto economy’s demand and supply of goods and services before and after the 1906 quake and fire continues in the living memory of descendants of family members who worked in some fashion for the gambling dens. The cash-rich operators of the gaming operations were viewed by many Chinatown as veritable kings who had the means to live well, arrange for women to enter the US to start families, and buy real estate openly or clandestinely during an era of alien land laws. The prevalence of large amounts of cash and contraband in Chinatown establishments providing opium or gambling to the public required security measures in the form of watchmen, armed guards, and fortified doors against interdiction by police and competitors.

In this context, we consider the next two photos of a “highbinder” whose work and home lives were captured in a remarkable pair of photographs sometime during the 1880’s.

As a veteran of the Chinatown beat, San Francisco Patrol Special officer Delos Woodruff (1834-1893) was best known for harnessing the new photographic technology of the day by compiling a book of mug-shots of his arrestees and suspects. He is often credited as the originator of the term “highbinder” in reference to the “hatchet men/boys,” “boo how doy” (Toisanese pronunciation), or 斧頭仔 (canto: “fu1 tau3 jai2”) who served as the soldiers or enforcers for the criminal tongs of Chinatown. As Richard H. Dillon wrote in his book, Hatchet Men, Woodruff was testifying in court when he declared: “A lot of highbinders came to the place—” whereupon the judge interrupted him with a gesture of his hand. “What do you mean by ‘highbinders?” Woodruff replied, “[w]hy a lot of Chinese hoodlums… .That’s what I call them.” (Dillon 21)

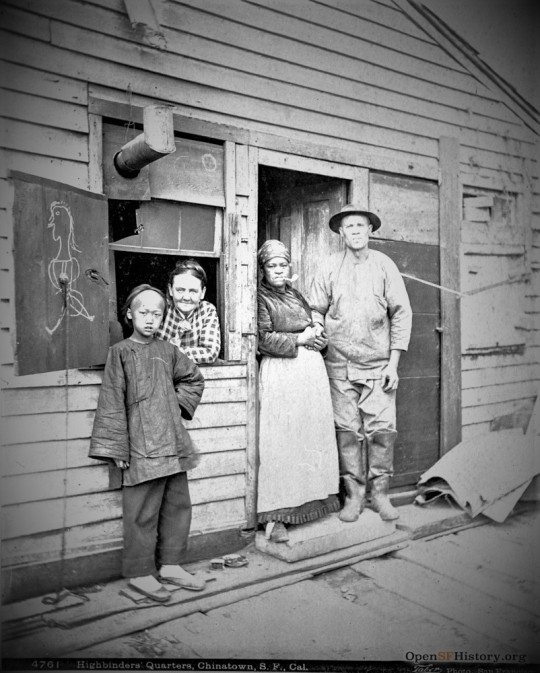

“4761 Highbinders' Quarters, Chinatown, SF, Cal.” c.1887. Photograph by Isaiah West Taber (Marilyn Blaisdell Collection / Courtesy of a Private Collector).

The volunteer curators at opensfhistory.org correctly note that I.W. Taber’s photo no. 4761 shows a “multiracial group of four people poses in front of a rustic shed; graffiti drawing of woman on left.” The adult Chinese man seen at right is only presumed to be a “highbinder” based on Taber’s caption. His working class garb provides no hints of his vocation other than knee-high work boots, which would suggest a job in an industrial concern such as a cigar or bootmaker.

Perhaps more startling is the pose of his presumed partner, an African American woman holding in both of her hands the Chinese man’s right hand on her left hip. The pose conveys an easy comfort and implicit intimacy between this multiracial couple in an era in which few photographic examples of such have survived. The couple is joined in the photo by a middle-aged white woman and a Chinese boy, whose relationships to the couple have remained unclear across the centuries (although the boy could have been the highbinder’s son).

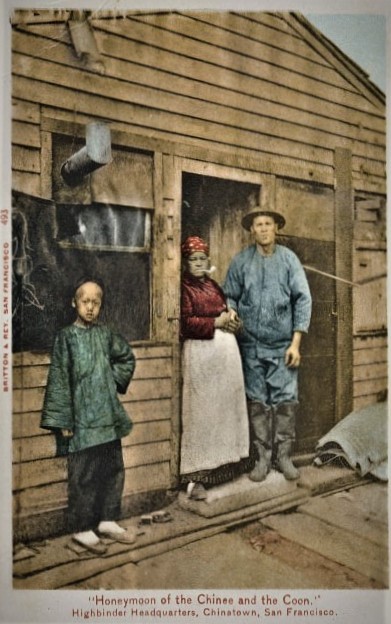

“’Honeymoon of the Chinee and the Coon.’ Highbinder Headquarters, Chinatown, San Francisco,” c.1887. Color postcard published by Britton & Rey, San Francisco, based on a photograph by I.W. Taber (from the collection of the California Historical Society).

As rare and surprising as it appears, the image of an interracial coupling by a Chinese man and African American woman was hardly novel for the Chinatown area of the late 19th century for at least three reasons.

First, San Francisco’s pioneer Black and Chinese communities lived in close proximity to each other. According to a city-sponsored study from 2016, “[t]he African American presence was densest in the eastern portion of this area. By the last quarter of the nineteenth century, one-third of the City’s Black population lived in a six-block area bounded by Stockton Street, Kearney [sic] Street, Washington Street, and Broadway. They lived among Chinese, Europeans, and American-born Whites. As shown … this area was served by two horse car street railways by the early 1860s and readily accessible to service jobs in the commercial core. ”

Second, California had enacted laws against the importation of Chinese, Japanese and Mongolian women five years before a federal ban. The state had cited the rise of prostitution crimes as the rationale for effectively discouraging Asian women from coming to California. The state law, 1870 Cal Stat 330, required that “Mongolian” women immigrants to prove that they were of good character.

In 1875, a new federal law barred entry of "Chinese, Japanese and Mongolian prostitutes, felons, and contract laborers," based on the assumptions that Asian women were “prostitutes” and Chinese laborers were indentured or “coolie” labor. The Page Act of 1875 (Sect. 141, 18 Stat. 477, 3 March 1875) was the first restrictive federal immigration law in the United States, which effectively prohibited the entry of Chinese women. The law was named after its sponsor, Representative Horace F. Page, a Republican representing California who introduced it to “end the danger of cheap Chinese labor and immoral Chinese women.” The law also technically barred immigrants considered “undesirable.”

Closing female Chinese immigration represented an explicit form of legislative genocide. Preventing women from immigrating alongside their partners meant male laborers were unable to create families and set down roots in America. Chinese males had little recourse except to earn and send money back to impoverished villages in southern China, with the hope of returning at some future time to rejoin their families. The Chinese, it was presumed, would either leave or die out over time in America.

Third, racist legal restrictions had severely limited the marriage and family choices for Chinatown’s working class males. From its inception, the state of California banned interracial marriage since achieving statehood in 1850. The initial statute of 1850 specifically banned interracial marriage between whites and blacks, declaring that “all marriages of whites with negroes or mulattoes are declared to be null and void” See, Cal. Compiled Laws of California Chapter XXXV Section 3 (Cal. Stat. 1850). The legislature later amended the statute to ban the marriage of whites with people from other racial minority groups, most likely because of an increasingly diverse population coupled with an “inclination to segregate” as demonstrated by the existence of an anti-miscegenation statute (Karthikeyan, Chin).

In 1905, the marriage of a white person to an Asian was explicitly banned. The language of the statute was changed so that “no license must be issued authorizing the marriage of a white person with a negro, mulatto, or mongolian.” See Cal. Compiled Laws of California Chapter CLXXXVI Section 69 (Cal. Stat. 1905). “Members of the Malay race” as part of those ineligible to marry whites were added to the law a quarter-century later. See Cal. Compiled Laws of California Chapter 104 Section 60 (Cal. Stat. 1933). Although a full discussion of California’s anti-miscegenation laws is beyond the scope of this article, suffice to say that the state’s principal focus for legislative action was to expand the classes of persons who were unworthy to marry a white person.

Resulting bachelorhood among Chinese male laborers defined life in old Chinatown for the next 70 years. The bachelor society also enhanced mainstream suspicions and served as the foundation for the Sojourner Myth and Perpetual Foreigner Syndrome, which permeates attitudes and writings about the Chinese American experience to this day. “They were portrayed as driftless," says Dr. Melissa May Borja, assistant professor in the Department of American Culture at the University of Michigan. “It enhanced the view that they shouldn’t be full Americans. Barriers justified other barriers.” Thus, the highbinder in Taber’s photo lived in a world in which he had few choices to build anything approaching a conventional home life.

As a legal issue, the statutory scheme largely ignored the issue of marriages between non-white persons.

Thus, the highbinder shown in Taber’s photo lived in a world in which he had few choices to build anything approaching a conventional home life. Far from home, denied a normal home life, a Chinese pioneer had found his solution to society’s limits on his world and a companion against the loneliness of his days in his new land.

“4765 Guard on Duty, Lottery Den, Chinatown, S.F., Cal." c. 1887. Photo by Isaiah West Taber (from the collection of Gallica, the digital library of the National Library of France and its partners).

I.W. Taber’s photo of a gambling den guard is seldom exhibited, and it is not easily accessible online from the usual public archival sources. However, Taber’s startling image answers the question why he referred to the man in the previous photo no. 4761 as a “highbinder.” The image also presents a rare and startling instance of the same subject appearing in two different photos of old Chinatown in two different venues.

I.W. Taber’s fascinating photo of a security guard for a Chinatown gambling seems to have attracted scant from researchers, archivists and museum curators about the nameless Chinese man who allowed Taber to photograph scenes of his home and work lives.

The stolidity of the guard imparts to the viewer that he is the principal guardian for the lottery den. Although he is seated, our highbinder projects a size and heft greater than presence of the more slightly-built man wearing the 瓜皮帽 (canto: “gwa pei moh”) or 小瓜帽 (canto: “siu gwah moh”) for headwear. The seated man displays a pair of large hands formed as half-fists between his knees. The standing man’s right hand is poised reflexively at belt height in front of his oversized jacket; he appears ready to reach inside, if necessary, for something concealed inside his garment. Both men stare into the camera’s lens with a blend of curiosity and relaxed concern, but without a sense of heightened readiness or fear. Perhaps the larger man has reassured his colleague that Taber’s presence posed no threat to their employer’s business.

The operators of Chinatown’s lottery took bets day and night on what the Chinese called “white pigeon.” Police Chief Jesse B. Cook wrote about lottery operations in a 1931 Chinatown beat memoir as follows:

“In regard to the gambling games in Chinatown—my first trip to Chinatown was in 1889 as a patrolman in a squad. At that time there were about 62 lottery agents, 50 fan tan games and eight lottery drawings in Chinatown. * * *

“The lottery drawings: The Chinese have a very large room, with the doors constructed the same as in the case of a fan tan game room. The far end of the room is partitioned off with wire screens to the full width and about 8 feet deep. In back of the screen are two shelves, one of which acts as a counter for four Chinamen. Each Chinaman has a separate window in the screen. On the other shelf are placed Chinese ink pots and brushes, for the purpose of marking Chinese lottery tickets. Every Chinese lottery ticket has 80 characters on it; 40 above the line and 40 below. Each company stamps their own name at the head of the ticket. These tickets are really a Chinese poem, written by a Chinaman while in prison, and later adopted as a Chinese lottery ticket. There is not a thing on these tickets to designate their real use, although they are never used for any other purpose.

“The agents around town had their offices in back of stores where they sell the tickets. Just before the drawing takes place, they present a triplicate copy of each ticket sold to the Chinaman at the window. The duplicate ticket is given to the purchaser, while the original is retained by the agent.

“The clerk back of the window then figures up the amount that the agent should turn in to cover the tickets sold. If they agree, the clerk accepts the tickets. No receipts are given. The actual taking and accepting of the tickets by the clerk is considered an acknowledgment, as his name appears on all the tickets.

“Sign says white persons, with or without guides, are barred from this Chinatown alley. As soon as all the money and tickets are in, the tickets are closed and the lottery is held. In a little package, about 2 inches square, are 80 slips of paper. On each of these slips is a character corresponding to one of the characters on the lottery ticket. The Chinaman sets in front of him a large pan, like the old-time milk pans we used to set for milk to raise cream, and four bowls, each bearing a Chinese number—either 1, 2, 3 or 4. The small slips of paper are folded into little pellets, thrown into the pan and shaken up. The drawing then begins. The first pellet drawn is put into bowl No. 1, the next into bowl No. 2, and so on, until there are twenty pellets in each bowl.

“The Chinaman then takes another small package, containing four little square pieces of paper. On each of these pieces is a figure in Chinese corresponding with the figures on the bowls. The same procedure is then followed as with the pellets. The slip picked from the pan is handed to the clerk, who in turn hands it to a man standing on the shelf in back of him. It is opened, in the presence of everybody gathered there. Of course, the bowl bearing the same number is considered the winning bowl, the other three are placed under the counter.

“The pellets are then taken from the winning bowl and are pasted on a board in full view. These are winning characters. The Chinese mark the tickets by daubing the characters that agree with the ones on the board, with a brush. After this has been done, they present their tickets, and come back at the proper time to get their reward; that is, whatever they won.

“In 1895, the lotteries and games were controlled by Chin Buck Guy, Chin Kim You, Wong You, Wong Fook, Jim Wong, Mah Lin Get, Chin Chung, Qwong Bin, who were sometimes called the “Big Eight.”

“The lottery companies at that time were the Tie Loy, Foo Quoy, Foo Quoy Chung, Fay Kay, Shang High, Fook Tie, Quong Tie, New York and Wing Lay Yuene.”

In his classic book San Francisco Chinatown: A Guide to its History and Architecture, historian Phil Choy wrote about the ultimate fate of Chinatown’s lottery:

“The casinos of Reno and Las Vegas copied this lottery and called it “Keno,” using numbers in lieu of the Chinese characters on the keno tickets. For almost a century, the policeman of the Chinatown Squad raided and battered down doors with axes to stop the illegal gambling, to no avail. However, when the federal government established the Kefauver Committee in 1950 to investigate narcotic trafficking and organized crime. Nationwide, Chinatown lotteries stopped abruptly. Congress enacted legislation requiring a federal tax stamp to operate gambling operations. Most of the Chinese lotteries were operated by Chinese with questionable immigration status. Rather than subject themselves to the scrutiny of federal authorities, they chose to close their operations.”

The Taber photo of the lottery den guards conveys an immediate sense that the games are conducted just beyond the double-doors set into a half moon-shaped entrance. Some deterioration in the wall above the entrance indicates water intrusion possibly from the skylight. Both men are washed by mid-day sunlight streaming through a skylight, above and behind the photographer’s position, and onto the landing where they stand guard. In the foreground at left, the last step of a staircase suggests that one more level to the topmost floor or roof can be reached from the landing on which the men stand watch. A semi-polished, wooden balustrade can be seen in the foreground from which the guards can look down into the building’s stairwell.

No weapons are evident, and the rugged-looking guard on duty for Taber’s “lottery den” may simply have performed the non-kinetic role of a “look-see” man whose job would have been to alert the lottery den’s operators and patrons of an imminent raid by police or other parties wishing to disrupt the gambling. Taber’s photo raises more questions than it answers, particularly about the working lives of fathers whose jobs were to look outward for threats and confront them, if necessary.

Fortunately for their as-yet unknown descendants, the two pairs of photographs captured the lives of two men from very different social positions. As such, they must be considered as the priceless tetraptych of old Chinatown.

[updated: 2022-7-24]

#Chinatown merchant#Chinatown highbinder#San Francisco Chinatown#Ross Alley#keno#Chinatown lottery#I.W. Taber#Page Act of 1875#California anti-miscegenation laws#African Americans in Chinatown#Charles Weidner#Jesse B. Cook

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

why is anti-asian racism............. fine

why is it so persistent and insidious

why is there always a new version of sinophilia that people cannot understand is racist

it was chinese people, it was japanese people, now it's korean people

i still have to see white people degrade chinese cuisine yet gobble it up every day of the year except thanksgiving and white artists making their names off of anime aesthetics and doing nothing to support the people they got that inspiration from and white people fetishizing the living hell out of korean people and turning a broad blind eye to the inhumanity of the kpop industry

and ya know, i see it from non-asian people of color too, it's just co-signing this continuous wave of colonialism against our bodies and culture

i want you to be aware of the fact that alongside black people, asians (as well as indigenous peoples in the territory the US claims) have been targeted by anti-miscegenation laws as recently as 1962. fun fact: filipinos have been separately categorized as another race away from asian that white people were banned from marrying since 1948. in the belief that filipino men would steal white women away from their rightful claim by white men.

asian immigration to the US was severely limited from 1882 until 1965 with the chinese exclusion act. 1965 is well with in the last 100 years. it is well within living memory.

the atrocities committed against filipinos alone in this country is horrific and nobody knows. look up the yakima valley riots. the watsonville riots. washington and california, respectively. and that goes without mentioning the sheer amount of exploitation of labor and degradation of our humanity.

every day millions of people turn a blind eye to anti-asian racism, including self-hating asians who throw others under the bus. the ones who "don't think that's racist". the ones who are so harmed by the pursuit of whiteness that they hate those who are being harmed right alongside them.

people will wring out every drop of aesthetic and whimsy from our cultures, holding the palatable parts as theirs to take while pushing the parts unappealing to western audiences away.

it just drives me fucking nuts

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

McKee’s / Gretna Green / Graceland Wedding Chapel, since c. 1939

(1) Photo c. 1940s. Manis Collection, UNLV Special Collections. (2, 3) Postcard dated July 7, 1949. (4, 5) Brochure, 1950s - courtesy of Stephanie DeAugustine. (6) Photo, 2005 - by Keith.

The wedding chapel at 619 Las Vegas Blvd S originally opened in a former private home in the 1930s and has remained in business for over 80 years under three names: McKee’s Wedding Chapel, Gretna Green, and Graceland.

The original residence was built in the 1920s. There are few clear records to show when Mrs. Ollie McKee opened the wedding business. The earliest record is a 1939 newspaper ad: “Wedding Chapel (McKee's) Open 24 hours. 619 South Fifth.”

The name “Gretna Green” was being used for the chapel in the early 40s. The name comes from the Scottish village known for “runaway marriages” in the 18th century, and was also the name of a popular Hollywood chapel in Glendale, California.

Former nearby chapels Wee Kirk o’ the Heather and Hitching Post were also opened in former homes. All three of them added steeple architecture to the buildings in the 1950s.

Graceland Chapel originally opened separately at a different location in the early ‘80s at 827 Las Vegas Blvd S, as the first fully Elvis-themed chapel. Graceland relocated in the late ‘80s to 619 Las Vegas Blvd S, taking the place of Gretna Green.

Note the legal requirements from the chapel’s brochure in the 1950s: “Persons of black, brown or yellow race cannot intermarry with those of the white race in the state of Nevada.” The Nevada legislature repealed the state's anti-miscegenation laws on 3/17/59.

Ad. Review-Journal, 12/6/39, p7; “Ruby Keeler's Sister Weds Here.” Review-Journal, 4/28/41; “Elvis Tribute.” Review-Journal, 1/5/84.

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

STYLE ICON: FRED KOREMATSU

by Daniel Penny

This past January 30th was Fred Korematsu Day, a state-wide holiday in California celebrating the legacy of Japanese American activist Fred Korematsu. Born in Oakland in 1919 to parents of Japanese ancestry who owned a flower nursery, Korematsu was one of three Japanese Americans who protested against the United States’ internment policy during World War II, eventually taking their case all the way to the Supreme Court.

His story was typical of many young American men of that era: he attempted to join the National Guard and Coast Guard in the run-up to the war, but was rejected on the basis of race. To help with the war effort, Korematsu decided to become a ship welder, but was fired from his job when FDR signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the internment of all Japanese-American citizens on the West Coast. In the spring of 1942, the Korematsu family was shipped to a horse racing track that had been converted into temporary housing, but Fred refused to report for relocation--going so far as to get cosmetic eyelid surgery and change his name to “Clyde Sarah” while claiming to be of Spanish and Hawaiian descent. Under his new name, he holed up in a boarding house, but was soon detected by police and arrested for disobeying military orders.

While in jail, Korematsu was contacted by the ACLU, who were hoping to use his case to challenge Japanese internment. In 1944, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 against him, citing military necessity. After the war, Korematsu moved to Michigan for school, married a white woman (which was permitted in Michigan but illegal in California due to anti-miscegenation laws), and moved back to the Oakland area, where he raised a family.

In 1983, legal scholars dug up Korematsu’s case, including evidence the government had intentionally suppressed reports that found no basis for the idea of Japanese Americans disloyalty. His conviction was vacated, and became the basis for a reexamination of the US government’s racist, unlawful wartime policies: he helped lobby for a Redress and Reparations bill signed by Reagan, and went on to receive a Presidential Medal of Freedom from Bill Clinton. And yet, Korematsu never settled for just a personal victory--extending his activism to Muslim detainees at Guantanamo and filing amicus briefs against the discriminatory actions of the Bush administration. Ironically, Korematsu’s conviction was finally overturned in 2018, years thirteen after his death--when the Supreme Court ruled to uphold President Trump’s Muslim ban. Today, his family continues his legacy, fighting for the civil rights of others who the government discriminates against under the cover of “security” and “military necessity.”

There are plenty of photographs of Korematsu from the second half of his life from when he reemerged in the public eye as a champion of civil rights (always nattily attired), but I’m often drawn to a picture taken of him as a young man, standing with his parents in their flower nursery. He wears a light blazer, v-neck sweater, and boldly patterned tie, his thick hair pushed back. There’s something about the way he carries himself, his implacability, his confident, direct gaze. It’s so quintessentially American.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dark kabaret san francisco

DOWNLOAD NOW Dark kabaret san francisco

As a Parsi, he was considered a "pure member of the Persian sect" and therefore a "free white person". īhicaji Balsara became the first known Indian to gain naturalized U.S. Many Indian men, especially Punjabi men, married Hispanic women, and Punjabi-Mexican marriages became a norm in the West. However, it was legal for "brown" races to mix. In some states, anti-miscegenation laws made it illegal for Indian men to marry white women. born children legally own the land that they worked on. However, Asian immigrants got around the system by having Anglo friends or their own U.S. In 1913, the Alien Land Act of California prevented non-citizens from owning land. Throughout the 1910s, American nativist organizations campaigned to end immigration from India, culminating in the passage of the Barred Zone Act in 1917. In the early 20th century, a range of state and federal laws restricted Indian immigration and the rights of Indian immigrants in the U.S. Although labeled Hindu, the majority of Indians were Sikh. officials, who pushed for Western imperial expansion abroad, casting them as a "Hindu" menace. politics and culture in the early 20th century, Indians were also racialized for their anticolonialism, with U.S. While anti-Asian racism was embedded in U.S. for Indians and Sikhs, who were called " hindoos" by locals. The Bellingham riots in Bellingham, Washington on September 5, 1907, epitomized the low tolerance in the U.S. Some white Americans, resentful of economic competition and the arrival of people from different cultures, responded to Sikh immigration with racism and violent attacks. Sikh workers were later concentrated on the railroads and began migrating to California around 2,000 Indians were employed by the major rail lines such as Southern Pacific Railroad and Western Pacific Railroad between 19. states in the 1900s to work on the lumber mills of Bellingham and Everett, Washington. 20th century Įscaping racist attacks in Canada, Sikhs migrated to Pacific Coast U.S. Swami Vivekananda arriving in Chicago at the World's Fair led to the establishment of the Vedanta Society. also helped develop interest in Eastern religions in the US and would result in its influence on American philosophies such as Transcendentalism. At the same time, Canadian steamship companies, acting on behalf of Pacific coast employers, recruited Sikh farmers with economic opportunities in British Columbia. between 18.) Emigration from India was driven by difficulties facing Indian farmers, including the challenges posed by the colonial land tenure system for small landowners, and by drought and food shortages, which worsened in the 1890s. (At least one scholar has set the level lower, finding a total of 716 Indian immigrants to the U.S. His race is listed as white, suggesting he was of British descent.īy 1900, there were more than two thousand Indian Sikhs living in the United States, primarily in California. Johns County, Florida, listed a 40-year-old draftsman named John Dick whose birthplace was listed as " Hindostan", living in city of St. The first Sikh Gurudwara was established in 1912 by the early immigrant Sikh farmers in Stockton, California. Indian Americans are included in the census grouping of " South Asian Americans", which includes Bangladeshi Americans, Bhutanese Americans, Nepalese Americans, Pakistani Americans, and Sri Lankan Americans. While "East Indian" remains in use, the term "Indian" and " South Asian" is often chosen instead for academic and governmental purposes. Since the 1980s, Indian Americans have been categorized as "Asian Indian" (within the broader subgroup of Asian American) by the United States Census Bureau. government has since coined the term "Native American" in reference to the indigenous people of the United States, but terms such as "American Indian" remain among indigenous as well as non-indigenous populations. Qualifying terms such as " American Indian" and " East Indian" were and still are commonly used in order to avoid ambiguity. In the Americas, the term "Indian" had historically been used to describe indigenous people since European colonization in the 15th century. 7.6.1 Deepavali/Diwali, Eid/Ramadan as school holidays.states by the population of Asian Indians metropolitan areas with large Asian Indian populations

DOWNLOAD NOW Dark kabaret san francisco

1 note

·

View note

Text

Interracial relationships

Today I went to Killerton House in Exeter with my mom and her boyfriend, Kuldeep. I wanted to take some images representing there interracial relationship. In order to do this, I asked Kuldeep if he could bring and change into his traditional Indian dress, which is called Sherwani. Kuldeep wore it to a wedding in India. I asked my mom to put on an outfit that she would typically wear when going out or to work. I did this in order to demonstrate the contrast between each of their ethnicity. Due to the strong love they hold for each other, they both love learning about and celebrating each others cultures. For example, this year they are celebrating both Diwali (which is celebrated by most Indians of all faiths across a 5 day period), and Christmas together.

In my research, I learnt that in the year 2000 the Sunday times reported that “ Britain has the highest rate of interracial relationships in the world”. An interracial relationship are those involving two people belonging to different ethnicities. As opposed to other countries, Britain is one where interracial marriage has always been legal and has always occurred, with the earliest interracial marriages dating back about 1950 years ago to when Roman soldiers from Africa and British women where getting married. However, other countries weren’t so accepting of interracial relationships, such as North America. Marriage for these couples wasn’t legalized in all states until 1967 when the US Supreme Court came to the decision that deemed anti - miscegenation state laws unconstitutional, with many states choosing to legalize interracial marriage at much earlier dates. This came after the Loving V. Virginia case; a landmark case concerning an interracial married couple living in Virgina. The High Court overturned Virginia’s anti - miscegenation law, rejecting the state’s defence that the statute applied to blacks and whites equally. The Virginia Law, the Court Stated, had no legitimate purpose except blatant racial discrimination as “measures designed to maintain white supremacy.” Nearly every state in the USA has had an anti - miscegenation law in place. Many State’s throughout the 1950’s followed California’s lead after the Californian Supreme Court overturned the state’s long standing anti - miscegenation statute in 1948.

“Marriage is one of the ‘basic civil rights of man,’ fundamental to our very existence and survival. ... To deny this fundamental freedom on so unsupportable a basis as the racial classifications embodied in these statutes, classifications so directly subversive of the principle of equality at the heart of the Fourteeth Amendment, is surely to deprive all the State’s citizens of liberty without due process of law.” - Chief Justice Warren, writing for The Court.

0 notes

Text

I've had these same conversations about miscegenation laws. Within living memory, there were laws on the books in many states prohibiting interracial marriage.

Loving v. Virginia was decided when my dad was thirteen years old.

Not my grandpa; my dad.

And there has been, in my lifetime, no movement whatsoever to bring those laws back.

I find that very interesting; I'm not claiming that racism has disappeared, or that interracial marriage is completely fine with everyone everywhere, but at the same time,

Roe V Wade was decided four years after Loving V Virginia. And there has been a 50 year fight to overturn it which succeeded just this year.

The fact that Loving V Virginia is over 50 years old is not why people don't campaign on overturning it, there's no grandfather clause for this stuff, decisions very nearly as old have stayed controversial and attracted massive opposition.

The fact that overturning Roe V. Wade has been a centerpiece of Republican political work while any Republican who suggested overturning Loving V. Virginia would be turned on by their own party actually means something, it is neither inevitable nor obvious that this should be the case.

So when I ask people, "Name a victory for affirmative action in the courts or the legislature which has happened in the past half-century" and people just... can't do it, that's interesting in exactly the same way that it's interesting that people can't name a victory in the courts or legislature for miscegenation laws in the last 50 years.

This is not just how things are in America, it's incredibly unusual. If I asked the same question, "Name a victory in the courts or legislature for X ideology" it would be incredibly easy to do so for almost any live political debate. For example, if I was like, "Name a court decision or passed law that increased gay rights within the last 50 years" nobody would feel the need to tell me some just-so stories about how left-wingers don't actually believe in the legal system so of course they eschew it and get around gay marriage laws through non-legal means;

You'd just say, "Lawrence V. Texas."

And if I asked the same thing about anti-gay activism, you'd say, "California proposition 8" or "DOMA".

It is neither normal nor inevitable for nearly the entirety of the successful work of the courts and legislature to fall on one side of an issue like this, and watching people pretend that it's just an obvious commonplace thing that doesn't have any consequences or implications really, really irritates me.

I get pissed off not because I'm incredibly pro-Afirrmative Action but because so much of the rhetoric against it involves cultivating a deep and deliberate ignorance about the last half-century of American history and that just pisses me off in and of itself.

The details matter. It matters that you can't just stick a "Whites only" (or for that matter "Blacks only") sign on the side of your college or business and have done with it.

Even though racism still exists that fact matters, damn it, history matters and I get really angry at the way so many people pretend it doesn't.

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today is LOVING DAY❤️ The day is named for the monumental case, Loving v. Virginia, and the interracial couple at its center, Richard and Mildred Loving. The 1967 Supreme Court decision struck down 16 state bans on interracial marriage as unconstitutional. In many states, anti-miscegenation laws criminalized marriage, cohabitation and sex between whites and non-whites. These laws had been in effect since the original 13 colonies in the early 18th century. Mildred Loving , a black woman, and Richard Loving, a white man, married in Washington, D.C., in 1958. They were arrested a few weeks after their marriage. They pleaded guilty to charges of "cohabiting as man and wife, against the peace and dignity of the Commonwealth". They were jailed on charges of unlawful cohabitation and offered a choice: either continue to serve jail time or leave Virginia for 25 years. They chose to avoid jail time by leaving the state of Virginia. They were forced to not to return to the state for 25 years. The Lovings moved to Washington, D.C., and began legal action by writing to then US attorney general Robert F Kennedy. The case took 10 years. Eventually the case Loving v. Virginia, invalidated laws prohibiting interracial marriage. The Supreme Court unanimously overturned the laws on June 12, 1967. Loving Day commemorates this 1967 landmark U.S. Supreme Court case.🤎🤍🖤 (at Los Angeles, California) https://www.instagram.com/p/CBWFOfJj6ZR/?igshid=1vs2csryik0cw

0 notes

Photo

“78. Chinese Women in Sutro Heights. San Francisco, Cal.” (a.ka. “Chinese Noble Women in Sutro Heights”) -- circa 1896 (Photograph by W.C. Billington from the Marilyn Blaisdell Collection)

When Chinese women ventured out into San Francisco’s Outside Lands

The presence of what appears to be unescorted Chinese women would have been unthinkable in the San Francisco of the two decades prior to when this extraordinary photograph was taken. Racial hostility by whites against Chinese throughout the American West, California, and San Francisco during 1870s and 1880s was stoked by dramatic population growth, economic depressions, the struggles of the organized labor movement against capital, and resulting high unemployment.

By the late 19th century, however, the Chinese Question had been resolved – unfavorably to the Chinese -- after the passage of national legislation in the form of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. The evil genius of exclusion, anti-miscegenation, alien land ownership prohibition, and other laws assured that the Chinese population would, in effect, simply die out by legislative genocide; violence to persons and property, while never technically legal, was no longer necessary.

In the meantime, money from the vast fortunes made in gold and silver mining and the benefits of railroad-driven technological and infrastructure development flowed into San Francisco of the Gilded Age. When the private economy and construction faltered, public works projects would help bridge economic recessions, including greater attention to the development of public amenities such as parks.

The engineer, politician and philanthropist Adolph Heinrich Joseph Sutro (April 29, 1830 – August 8, 1898) served as the 24th mayor of San Francisco from 1895 until 1897. After his German-Jewish family immigrated to the US in 1850 and San Francisco in 1851, Sutro moved to Virginia City, Nevada. He made a fortune from mining operations in the Comstock Lode after obtaining financing and constructing a “Sutro Tunnel” to drain water from the silver mines and eliminate the threat of flooding.

Sutro increased his wealth by real estate investments back in San Francisco, including Mount Sutro, Land’s End (the area where Lincoln Park and the Cliff House are located today), and Mount Davidson. In 1881, Sutro purchased 22 acres of undeveloped land south of Point Lobos (San Francisco) and north of Ocean Beach at the western edge of the city. It included a promontory overlooking the Pacific, with scenic views of the Marin Headlands, Mount Tamalpais, and the Golden Gate. Sutro built his mansion on a rocky ledge there, above the first Cliff House.

“In 1885,” according to the Golden Gate National Recreation Area history, “self-made millionaire Adolph Sutro created the Sutro Heights Park, an elegant and formal public garden that covered over twenty acres in the area now known as Land’s End. Inspired by the rugged beauty and incredible scenery, Sutro intentionally designed the grounds to capture the views of the Pacific Ocean, the Golden Gate and the Marin Headlands.” Admission was open to the public for a donation of ten cents to defray the costs of maintain the grounds. For more information see: https://www.nps.gov/goga/learn/historyculture/sutro-heights.htm

Sutro’s opening his park to all, including Chinese, calls attention to the unusual presence recorded by the above photo, taken on the grounds of his Sutro Heights park, circa 1896.

The photo depicts the view north beside Palm Drive of five women in traditional Chinese dress. Sutro’s statuary of “Venus de Milo” and a Gryphon, planters, and palm trees can be seen, along with the main gate in the background. Less obvious (in the left third of the photo) is the presence of a man staring at the five women while standing next to a ladder in the background. The onlooker probably worked as one of the 17 full-time gardeners, machinist and drivers whom Sutro employed to maintain a collection of flower beds, forests, elegant wide walkways, hedge mazes and "parterres" (a popular Victorian landscape feature where flowers and bushes were carefully trimmed into shapes of names or designs). See: https://www.nps.gov/goga/learn/historyculture/sutro-heights.htm

However, no Chinese workers would have been present on the grounds that day -- or ever. Sutro bragged that, although he employed fourteen thousand men, he had never engaged a “Chinaman.” He wrote, “The very worst emigrants from Europe are a hundred times more desirable than these Asiatics.”

Of the five women shown in the photograph, not all of them may have qualified for Chinatown’s noble” class. The relatively plain dress and slippers worn by the two women at the left indicate that they may have been house servants. The other three young women wear more elaborate, and expensive, attire and footwear. The photograph notably captures smiles on the faces of at least two of the women, from which one can infer that they were enjoying the outing on the far western side of the City. Based on what is known about the lives of Chinese America’s first women, a walk through Sutro’s gardens probably represented a welcome change from their everyday routine.

“Chinese Women in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, Feb. 22, 1900.” Photographer unknown (from the Marilyn Blaisdell collection). A rare shot of Chinese women visiting the park, apparently unaccompanied by any male.

The absence of any male in the frame of the first photo is telling and unusual outside of Chinatown. Historian Jack Tchen, in his 1984 book, Genthe’s Photographs of San Francisco’s Old Chinatown, wrote about the lives of early Chinese American women on the urban frontier as follows:

“The women who came to America were limited to three primary occupational roles. They were usually either a merchant's wife, a house servant, or a prostitute. In the rural wilds of Idaho, Montana, and the Western frontier, local folklore has portrayed a few Chinese women as rugged and liberated frontier settlers; however, the women in San Francisco's Tangrenbu [唐人埠] were closely guarded and highly valued commodities. Merchants could freely bring their wives over and establish families. Abiding by traditional customs, these women were seldom seen in the streets of Chinatown. The great majority of men did not have the right to have a family. Before and after 1882, certain tongs specialized in smuggling young Chinese women past United States immigration agents. To enable them to pay their way to this country, exploitative contracts were drawn up similar to those many poor male workers came under. However, there was a significant difference: where the men paid off their debts with their labor, women paid off their debts with their labor and their bodies. . . .

* * * “Young girls would start off as house servants and occasionally work at odd jobs like stripping tobacco. Upon reaching a certain age they would either marry a wealthy merchant or enter into several years of prostitution. Some merchants considered experienced prostitutes ideal wives because they were attractive, sociable, and adept at entertaining guests. House servants were treated with varying degrees of respect and disrespect, depending on the individual character of the families they serve. Some young girls were brutally treated. They worked hard and were sometimes horribly beaten. Others were treated like members of the family. . . . * * * “The options available to Chinese children in the United States were severely limited both by the discriminatory laws of the larger society by the role expectations of the tradition-bound culture they came from. It would take some 40 years after these photographs were made for the laws and cultural restraints send their hold sufficiently to allow them a wider range of possibilities.”

In 1896, the same year during which the photo of five Chinese women was supposedly taken, Sutro would build a new Cliff House below his estate on the bluffs of Sutro Heights and start construction of the famous Sutro Baths.

As for the photographer, William Charles Billington, the National Park Service’s history recounts that he and his partner, Thomas Thomson, operated a photography studio at the Sutro Heights parapet, which they opened in 1894. They would take tintype photos of visitors, usually with the Cliff House as a backdrop, and scenic Land's End photos. As evidenced by the card variant of first photo in this series, the images would be reproduced in postcard format for sale to tourists, an example of which appears below.

As evidenced by the above variant of first photo in this series (from the Bob Bragman Collection), the images would find their way into postcard formats for sale to tourists.

In 1896, Billington’s company opened a studio on Point Lobos, the Cliff Photo Gallery, also at San Francisco's west end. His brother, John, would join the business and continue it after William’s death until 1925.

John Billington might have been the photographer of this photo of three Chinese women in traditional dress with a very poised girl in more modern apparel strolling down Palm Avenue, enjoying Sutro’s garden, in 1910 for a welcome break from Chinatown’s urban confines.

Chinese women and a child on Palm Avenue in Sutro Heights, circa 1910. Photographer Unknown (J. Billington?)

As for the Sutro estate and park, the Sutro family donated the land to the City of San Francisco in 1938. In 1939, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) demolished the residence which had fallen into decay. The WPA crews removed the remaining statuary, with the exception of The Lions (copies of those in London's Trafalgar Square at the entrance gate), and a statue of Diana the Huntress (Artemis), a concrete copy of the Louvre's Diana. An 18-acre city park then opened, eventually becoming part of the federal Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

For the Chinese, the photographs of women in Sutro Heights implicitly convey the relative security of the unequal peace of the 1890s -- gained by Exclusion and a network of laws and policies that confined most of their opportunities to Chinatown; the resulting small population, with its dwindling labor force, no longer posed a threat to white dominance of the urban frontier, such that even the “noble” women of Chinese America could travel to San Francisco’s Outside Lands without fear of violence or other hindrance.

[updated 2023-8-4]

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

An interesting read about Asian Masculinity in the United States that I saw on facebook.

There's a reason why Asian men in television and film are portrayed as sexually awkward and emasculate... and it has a lot to do with this picture.

In the early 1900's, a massive wave of Filipino men (aka, Manongs) immigrated to California to work on farms, canning factories, and fishing boats. The pay was shit but the allure of owning a home in America was too tantalizing to pass up. Since Filipina women were prohibited from immigrating with men, towns all around California quickly filled up with single, sweaty, and good lookin' Filipino men. These Manilatowns were packed to the brim with stylish Filipino bachelors who spent their money on new suits and their time at taxi dance halls #AmericasFirstFuckboys #JustKidding #SorryGrandpa Taxi dance halls were immensely popular among Filipino bachelors which provided both entertainment and sexual attention. For only ten cents, Filipino men could dance with first-generation European immigrant women, show off their outfits of the day, and romance their way to secret relationships that were illegal under anti-miscegenation laws. Despite racist laws, these interracial relationships continued to blossom and included relationships between Filipino men and Italians, Irish, Mexicans, and Black women. Word spread about the Manongs and white men were (for lack of a better term) TRIGGERED AS FUCK: "Some of these [Filipino] boys, with perfect candor, told me bluntly and boastfully that they practice the art of love with more perfection than white boys, and occasionally one of the [white] girls has supplied me with information to the same effect." The reality of Filipino men -- who were seen as small, weak, and inferior to white American men -- falling in love with white women become such a problem that mobs of masked white men started to raid, brutalize, and even kill the Manongs. Many of their assaults were directed at Filipino men's groins: "Another man, the one called Jake, tied me to a tree. Then he started beating me with his fists... A tooth fell out of my mouth, and blood trickled down my shirt. The man called Lester grabbed my testicles with his left hand and smashed them with his right fist. The pain was so swift and searing." ________________________________ So the next time you hear one of those bullshit stereotypes about Asian men, look back in American history and ask yourself, "WHY was America so obsessed with emasculating Asian men?" or "Why do they constantly talk about Asian men's penises?" You'll quickly realize that it has nothing to do with stereotypes being true or false, and everything to do with white male insecurity.

Source: The Love Life Of An Asian Guy

0 notes

Text

Forced sterilization programs in California once harmed thousands – particularly Latinas

http://bit.ly/2pydQfW

Postcard of the Napa State Hospital in Napa, Calif., circa 1905. Over 1,900 Californians were recommended for sterilization while patients here. The collection of Alex Wellerstein

Leer en español.

In 1942, 18-year-old Iris Lopez, a Mexican-American woman, started working at the Calship Yards in Los Angeles. Working on the home front building Victory Ships not only added to the war effort, but allowed Iris to support her family.

Iris’ participation in the World War II effort made her part of a celebrated time in U.S. history, when economic opportunities opened up for women and youth of color.

However, before joining the shipyards, Iris was entangled in another lesser-known history. At the age of 16, Iris was committed to a California institution and sterilized.

Iris wasn’t alone. In the first half of the 20th century, approximately 60,000 people were sterilized under U.S. eugenics programs. Eugenic laws in 32 states empowered government officials in public health, social work and state institutions to render people they deemed “unfit” infertile.

California led the nation in this effort at social engineering. Between the early 1920s and the 1950s, Iris and approximately 20,000 other people – one-third of the national total – were sterilized in California state institutions for the mentally ill and disabled.

To better understand the nation’s most aggressive eugenic sterilization program, our research team tracked sterilization requests of over 20,000 people. We wanted to know about the role patients’ race played in sterilization decisions. What made young women like Iris a target? How and why was she cast as “unfit”?

Racial biases affected Iris’ life and the lives of thousands of others. Their experiences serve as an important historical backdrop to ongoing issues in the U.S. today.

‘Race science’ and sterilization

Eugenics was seen as a “science” in the early 20th century, and its ideas remained popular into the midcentury. Advocating for the “science of better breeding,” eugenicists endorsed sterilizing people considered unfit to reproduce.

Under California’s eugenic law, first passed in 1909, anyone committed to a state institution could be sterilized. Many of those committed were sent by a court order. Others were committed by family members who wouldn’t or couldn’t care for them. Once a patient was admitted, medical superintendents held the legal power to recommend and authorize the operation.

Eugenics policies were shaped by entrenched hierarchies of race, class, gender and ability. Working-class youth, especially youth of color, were targeted for commitment and sterilization during the peak years.

Eugenic thinking was also used to support racist policies like anti-miscegenation laws and the Immigration Act of 1924. Anti-Mexican sentiment in particular was spurred by theories that Mexican immigrants and Mexican-Americans were at a “lower racial level.” Contemporary politicians and state officials often described Mexicans as inherently less intelligent, immoral, “hyperfertile” and criminally inclined.

These stereotypes appeared in reports written by state authorities. Mexicans and their descendants were described as “immigrants of an undesirable type.” If their existence in the U.S. was undesirable, then so was their reproduction.

Targeting Latinos and Latinas

In a study published March 22, we looked at the California program’s disproportionately high impact on the Latino population, primarily women and men from Mexico.

A sample sterilization form for a 15-year-old woman in California. Sterilization and Social Justice Lab, University of Michigan, CC BY-SA

Previous research examined racial bias in California’s sterilization program. But the extent of anti-Latino bias hadn’t been formally quantified. Latinas like Iris were certainly targeted for sterilization, but to what extent?

We used sterilization forms found by historian Alexandra Minna Stern to build a data set on over 20,000 people recommended for sterilization in California between 1919 and 1953. The racial categories used to classify Californians of Mexican origin were in flux during this time period, so we used Spanish surname criteria as a proxy. In 1950, 88 percent of Californians with a Spanish surname were of Mexican descent.

We compared patients recommended for sterilization to the patient population of each institution, which we reconstructed with data from census forms. We then measured sterilization rates between Latino and non-Latino patients, adjusting for age. (Both Latino patients and people recommended for sterilization tended to be younger.)

Latino men were 23 percent more likely to be sterilized than non-Latino men. The difference was even greater among women, with Latinas sterilized at 59 percent higher rates than non-Latinas.

In their records, doctors repeatedly cast young Latino men as biologically prone to crime, while young Latinas like Iris were described as “sex delinquents.” Their sterilizations were described as necessary to protect the state from increased crime, poverty and racial degeneracy.

Lasting impact

The legacy of these infringements on reproductive rights is still visible today.

Recent incidents in Tennessee, California and Oklahoma echo this past. In each case, people in contact with the criminal justice system – often people of color – were sterilized under coercive pressure from the state.

Contemporary justifications for this practice rely on core tenets of eugenics. Proponents argued that preventing the reproduction of some will help solve larger social issues like poverty. The doctor who sterilized incarcerated women in California without proper consent stated that doing so would save the state money in future welfare costs for “unwanted children.”

The eugenics era also echoes in the broader cultural and political landscape of the U.S. today. Latina women’s reproduction is repeatedly portrayed as a threat to the nation. Latina immigrants in particular are seen as hyperfertile. Their children are sometimes derogatorily referred to as “anchor babies” and described as a burden on the nation.

Reproductive justice

This history – and other histories of sterilization abuse of black, Native, Mexican immigrant and Puerto Rican women – inform the modern reproductive justice movement.

This movement, as defined by the advocacy group SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective is committed to “the human right to maintain personal bodily autonomy, have children, not have children and parent the children we have in safe and sustainable communities.”

As the fight for contemporary reproductive justice continues, it’s important to acknowledge the wrongs of the past. The nonprofit California Latinas for Reproductive Justice has co-sponsored a forthcoming bill that offers financial redress to living survivors of California’s eugenic sterilization program. “As reproductive justice advocates, we recognize the insidious impact state-sponsored policies have on the dignity and rights of poor women of color who are often stripped of their ability to form the families they want,” CLRJ Executive Director Laura Jiménez said in a statement.

This bill was introduced on Feb. 15 by Sen. Nancy Skinner, along with Assemblymember Monique Limón and Sen. Jim Beall.

If this bill passes, California would follow in the footsteps of North Carolina and Virginia, which began sterilization redress programs in 2013 and 2015.

In the words of Jimenez, “This bill is a step in the right direction in remedying the violence inflicted on these survivors.” In our view, financial compensation will never make up for the violation of survivors’ fundamental human rights. But it’s an opportunity to reaffirm the dignity and self-determination of all people.

Nicole L. Novak has received funding from the National Human Genome Research Institute at the National Institutes of Health.

Natalie Lira has previously received funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

0 notes

Text

Loving Selected Best Picture of 2016; Denzel Washington and Annette Bening Score Top Acting Honors

Star-Studded Annual Awards to be celebrated in Los Angeles on Monday, February 6, 2017

Through Weekly News And Reviews, Nationwide Screenings, And An Annual Awards Event, The Movies For Grownups® Initiative Champions Movies For Grownups, By Grownups.

AARP The Magazine today announced the winners of the 16th Annual Movies for Grownups® Awards. In doing so, the editors continue their integral role in awards season by honoring the best films with unique appeal to movie lovers with a grownup state of mind and by recognizing the inspiring artists who make them. With Loving and Denzel Washington and Annette Bening among the top honorees, this year’s winners will be celebrated at AARP Movies for Grownups® Awards on February 6, 2017. Three-time Emmy award-winning film and stage actress Margo Martindale will host the evening at the historic Beverly Wilshire in Los Angeles. (Chase Card Services, through its AARP® Credit Card from Chase, is the presenting sponsor of AARP’s Movies for Grownups® Awards event.)

Movies For Grownups logo (PRNewsFoto/AARP)

With more than 37 million readers, AARP The Magazine is the world’s largest circulation magazine and the definitive lifestyle publication for Americans 50-plus. AARP The Magazine delivers comprehensive content through health and fitness features, financial guidance, consumer interest information and tips, celebrity interviews, and book and movie reviews. AARP The Magazine was founded in 1958 and is published bimonthly in print and continually online. (Learn more at www.aarp.org/magazine/. Twitter: www.twitter.com/AARP)

The annual Movies for Grownups® Awards raises funds for the AARP Foundation, AARP’s affiliated charity, which helps struggling people 50-plus in Los Angeles and around the country transform their lives through programs, services and vigorous legal advocacy. The foundation works to ensure that low-income older adults have nutritious food, functional and affordable housing, steady income, and strong and sustaining social bonds.

The AARP Foundation is active in Los Angeles and working with the Motion Picture &Television Fund (MPTF) to develop programs to reduce social isolation among older people, by keeping them connected with their friends, families and neighborhoods. The Foundation also is the founding sponsor of L.A. Kitchen, where California produce considered “waste” is used to make healthy meals for those in need.

And The Award Goes To…..

Best Picture goes to Loving, the story of Richard and Mildred Loving, an interracial couple, whose challenge of the anti-miscegenation law in Virginia went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Annette Bening and Denzel Washington lead this year’s acting honorees and will take home Best Actress and Best Actor awards for their work in 20th Century Women and Fences, respectively.

This year’s Best Supporting Actress award will go to Viola Davis for her outstanding performance in Fences and Jeff Bridges earns the Best Supporting Actor for his performance in Hell or High Water. This year’s Best Director and Best Screenwriter awards will go to Kenneth Lonergan for Manchester by the Sea. Actor, producer and Academy Award-winner Morgan Freeman will receive the evening’s highest honor, the 2016 Movies for Grownups Career Achievement Award.

“AARP is delighted to celebrate the very best movies of 2016 and the outstanding work by the filmmakers and actors who make them,” says Myrna Blyth, Senior Vice President and Editorial Director for AARP Media. “These are the top movies for grownups made by tremendously talented grownups.”

“AARP’s Movies for Grownups Awards is one of the loveliest events of the season, one that is intimate and elegant and honors the films, filmmakers and film actors that people really respond to,” says actress Margo Martindale.

The (Complete List for the) 16th Annual Movies for Grownups® Award Winners are:

Best Picture: Loving

Best Actress: Annette Bening (20th Century Women)

Best Actor: Denzel Washington (Fences)

Best Supporting Actress: Viola Davis (Fences)

Best Supporting Actor: Jeff Bridges (Hell or High Water)

Best Director: Kenneth Lonergan (Manchester by the Sea)

Best Screenwriter: Kenneth Lonergan (Manchester by the Sea)

Best Comedy/Musical: La La Land

Breakthrough Achievement: Robert Mrazek (The Congressman)

Best Grownup Love Story: Margo Martindale and Richard Jenkins (The Hollars)

Best Documentary: The Beatles: Eight Days a Week

Best Intergenerational Film: 20th Century Women

Best Buddy Picture: Jennifer Saunders and Joanna Lumley (Absolutely Fabulous: The Movie)

Best Time Capsule: Jackie

Best Movie for Grownups Who Refuse to Grow Up: Kubo and the Two Strings

Best Foreign Language Film: Elle (France)

For more information about AARP‘s Movies for Grownups® Awards, go to www.aarp.org/moviesforgrownups. The entire list of award winners will also be featured in the February/March Issue of AARP The Magazine, available in homes February 1st.

The AARP is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization, with a membership of nearly 38 million that helps people turn their goals and dreams into ‘Real Possibilities‘ by changing the way America defines aging. With staffed offices in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, AARP works to strengthen communities and promote the issues that matter most to families such as healthcare security, financial security and personal fulfillment. AARP also advocates for individuals in the marketplace by selecting products and services of high quality and value to carry the AARP name. As a trusted source for news and information, AARP produces the world’s largest circulation magazine, AARP The Magazine and AARP Bulletin. AARP does not endorse candidates for public office or make contributions to political campaigns or candidates. To learn more, visit www.aarp.org or follow @aarp and the CEO @JoAnn_Jenkins on Twitter.

AARP The Magazine Announces The 16th Annual Movies For Grownups® Award Winners Loving Selected Best Picture of 2016; Denzel Washington and Annette Bening Score Top Acting Honors Star-Studded Annual Awards to be celebrated in Los Angeles on Monday, February 6, 2017…

#16th Annual Movies for Grownups® Awards#2016 Movies for Grownups Career Achievement Award.#AARP Bulletin#AARP Movies for Grownups® Awards#AARP The Magazine#AARP® Credit Card from Chase#Annette Bening#DENZEL WASHINGTON#Jeff Bridges#Jennifer Saunders and Joanna Lumley#Kenneth Lonergan#Margo Martindale#Morgan Freeman#Richard and Mildred Loving#the AARP Foundation#the Motion Picture &Television Fund (MPTF)#Viola Davis

0 notes