#Cahiers du Cinema

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

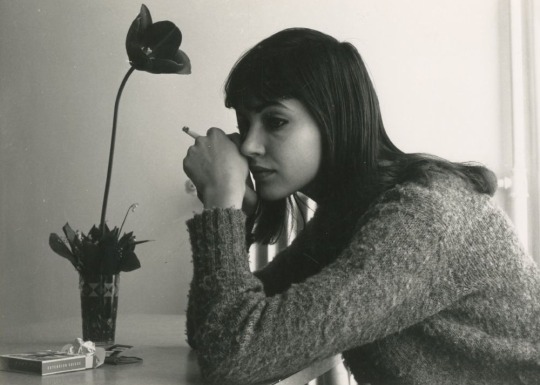

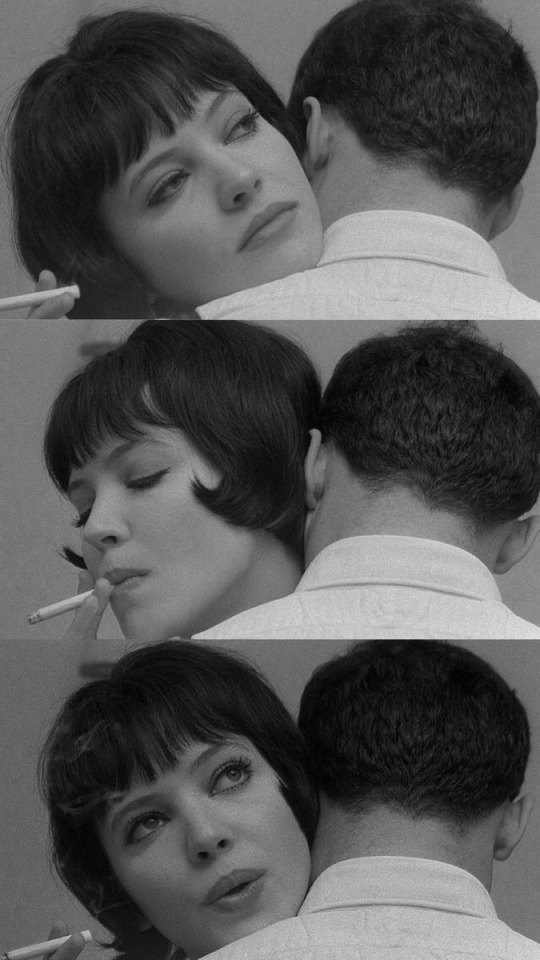

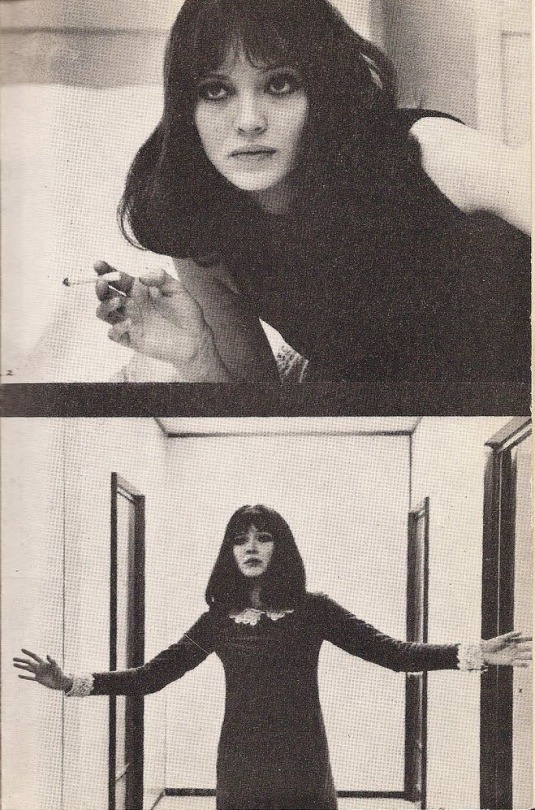

Anna Karina. Muse of the cult director of the new wave Jean-Luc Godard.

Photos from different years

#anna karina#jean luc godard#actor#film#art#movies#photography#magazine#french#french new wave#cinema#cahiers du Cinema#andre bazin#jean luc godard films#cinemetography#cinephile#french film#50s movies#60s fashion#60s film#black and white aesthetic#love

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

#cahiers du cinema#rohmer#pascale ogier#Les Nuits de la pleine lune#cinema#France#Tcheky Karyo#Mondrian

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

1976.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cahiers du Cinema - Jean-Luc Godard, Luchino Visconti. Octobre 1965

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

notes on the commercial failure (note sur l'insuccès commercial, cahiers du cinéma no. 143, may 1963), jacques rivette

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

New David Lynch art from the recent special Lynch issue of Cahiers du Cinéma: WHAT DID SHE SAY? (2017-2023, paint/mixed media)

“Wh.. Wh What did she say to me at her house”

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

298 - A Perfect World

Early in the 1990s, two westerns emerged as Best Picture winners when the genre was first thought dead: Kevin Costner's Dances with Wolves and Clint Eastwood's Unforgiven. In 1993, those heralded actor-directors would unite for A Perfect World, casting Costner as an escaped convict who takes a small boy hostage and teaches him about masculinity, with Eastwood as the lawman in pursuit while also taking the directing reigns. That pedigree missed the Academy on this round, however, as the film's downer telling was a poor fit to the holiday season to which it was launched.

This episode, we talk about the early poor reception for Costner's new saga Horizon and our differing opinions on this film's approach to masculinity. We also talk about Eastwood's output in the 1990s, Laura Dern's underserved role as a criminologist, and how the film disappointed for denying audiences an onscreen showdown between its male stars.

Topics also include Schindler's List as the 1993 undeniable frontrunner, Costner's sex appeal, and the Cahiers du Cinema.

The 1993 Academy Awards

Subscribe:

Patreon

Spotify

Apple Podcasts

#Clint Eastwood#Kevin Costner#Laura Dern#Bradley Whitford#Ray McKinnon#Mary Alice#Best Director#Academy Awards#Oscars#Cahiers du Cinema#movies

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Les sièges de l'Alcazar (Luc Moullet, 1989)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

LAS COSAS DE LA VIDA - Les choses de la vie (Francia, Italia, 1970)

LAS COSAS DE LA VIDA – Les choses de la vie – dirigida por Claude Sautet – Francia, Italia, 1970 – drama, romance – 85 Melodrama a la europea con ribetes existenciales sobre la indecisión de un individuo en la encrucijada de su vida. Adaptación de la novela Intersection de Paul Guimard, la cual fue retomada en 1994 con su título original en una versión para Hollywood, protagonizada por Richard…

#caarcas#Cahiers du cinema#Claude Sautet#Intersection#Julio Cortázar#la estrella lloró rosa#LAS COSAS DE LA VIDA#Les choses de la vie#Mark Rydell#Max y los chatarreros#Michel Piccoli#Paul Guimard#Richard Gere#Romy Schneider#rosas terrestres#Sharon Stone

1 note

·

View note

Text

Joy of Learning (Le Gai savoir), 1969, Jean-Luc Godard.

#movies#french film#jean luc godard#godard#swiss film#french cinema#french new wave#pierrot le fou#Nouvelle Vague#anna karina#Cahiers du Cinéma#robert bresson#françois truffaut#claude chabrol#existentialism#eric rohmer#rivette#maoist#jacques demy#agnes varda#vivre sa vie#breathless#1960s#le petit soldat#Le Mépris#Band of Outsiders#La Chinoise#Joy of Learning#1969

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

L'Ombre Familiere (1958), dir. Maurice Pialat

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

i left w no money and a cleo de 5 a 7 poster

1 note

·

View note

Text

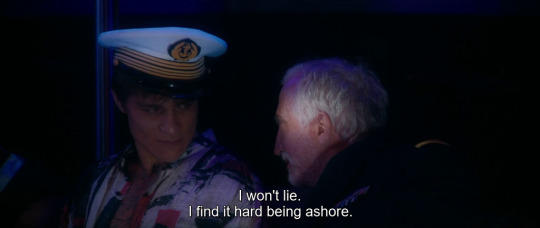

Pacifiction (2022) ------------------- dir. Albert Serra cin. Artur Tort cs. Spain, France, Germany, Portugal

#pacifiction#albert serra#artur tort#french cinema#french films#2022 films#Benoît Magimel#marc susini#Cahiers du cinéma

0 notes

Note

hi Deah do you have any film related books that you would recommend or ones that you personally have found interesting/taught you valuable info about understanding and or making movies appreciation and thanks in advance if you do have some ur open to sharing 😌

hello! I should really expand my reading but some titles I do like from my areas of interest:

In the Blink of An Eye (Walter Murch) - as an editor this is my bible it really breaks down everything I love about film personally and gives me lot of inspiration

Film Art: An Introduction (Bordwell & Thompson) - I had to read a most of this in the early years of my degree and if you don't know a lot whole lot about film it's genuinely very helpful learning cinematic techniques and languages. I think it's also really great at showing what it is that makes hollywood/western cinema work for mainstream audiences which, if you're serious about film, I think is very important to learn regardless of of how limited one might think that world is + they release new editions every couple of years to include up-to-date examples on newer movies

New Queer Cinema: The Director's Cut (B. Ruby Rich) and also The Celluloid Closet (Vito Russo) - very obvious, but still very important to understanding lgbt cinema history and achievements. they're not the only books but they're the most accessible ones to start with.

Monsters in the Closet: Homosexuality and the Horror Film (Benshoff) - book on queer-coding in horror from the 90s which DEFS needs an update but I think is still good.

It Came From the Closet: Queer Reflections on Horror (Vallese) - got this as a gift and have unfortunately not read yet but I believe it IS the update for the above listed book I've been waiting for + the contributors are excellent

The Monstrous Feminine & The Return of the Monstress Feminine (Barbara Creed) - wish this was a bit more diverse but still makes great points about women in cinema

Slow Cinema (Tiago & Jorge) - collection of essays about 'slow cinema' and filmographies by directors like Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Tsai Ming-liang, Lav Diaz etc

Reality Hunger (David Shields) - not fully focused on film but a great manifesto and gives you good background if you're thinking of getting into experimental film/media

I also really love review compilation books by critics! The Great Movies by Roger Ebert taught me a lot when I was teenager (unpacks the filmbro canon VERY well) and also Jim Ridley collection People Only Die of Love In Movies

+ love when there are 'movie companion'/visual guide books of my favourite films. I especially love the one for treasure planet and also recently A Vast Pointless Gyration of Gas and Rocks Oh My GoD the full title is so long but it's for everything everywhere all at once.

also I read a lot of source material for book adaptation films because I like to one-up everything I watch + adaptation as an art form fascinates me seeing which parts of a narrative work and don't work between mediums, often giving me a greater appreciation for one or both.

some magazines/publications I like to check out every once in a while: Little white lies, metro magazine (australia), senses of cinema, cahiers du cinema, sight & sound, the film stage

121 notes

·

View notes