#C.R.W. Nevinson

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

'Walkers, for a good start use the motor-bus'

London Transport poster featuring a man and a woman dressed in outdoor walking clothes and carrying walking sticks (c. 1920). Artwork by C.R.W. Nevinson.

#vintage poster#1920s#london transport#C.R.W. Nevinson#hiking#walking#transportation#public transport#countryside

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (British, 1889-1946), London Triumphant in the Fourth Year of the War: From the Dorchester Roof, Looking South-West, 1941. Pencil and oil on panel, 11 7/8 x 18 in.

#christopher richard wynne nevinson#english art#british art#london#C. R. W. Nevinson#c.r.w. nevinson

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

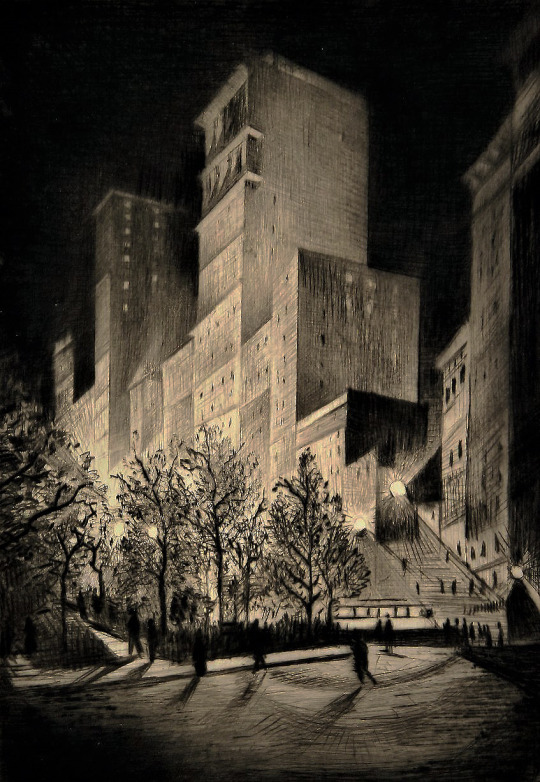

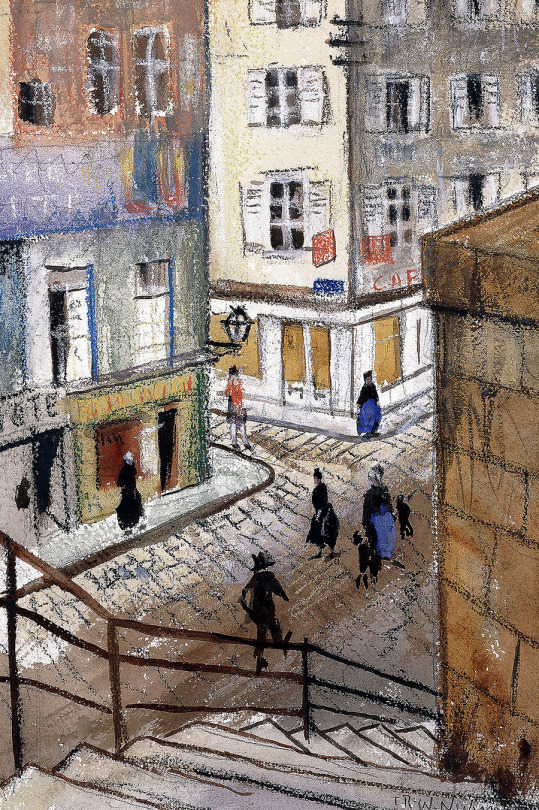

C.R.W Nevinson - Leicester Square (1926-27)

158 notes

·

View notes

Text

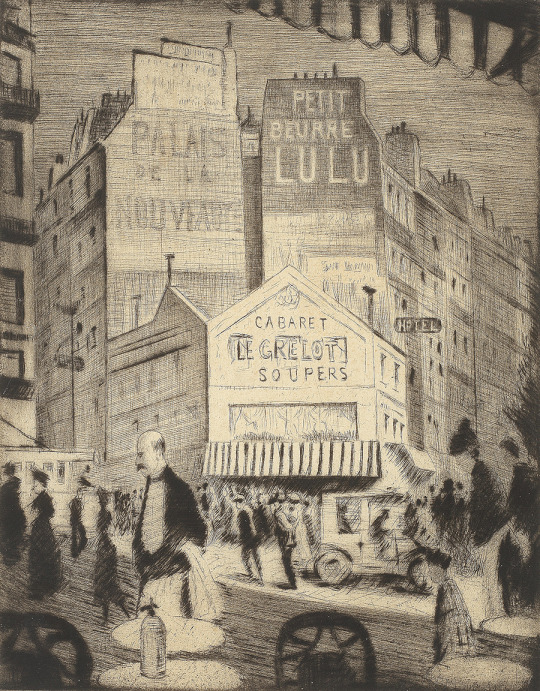

C.R.W. Nevinson.

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

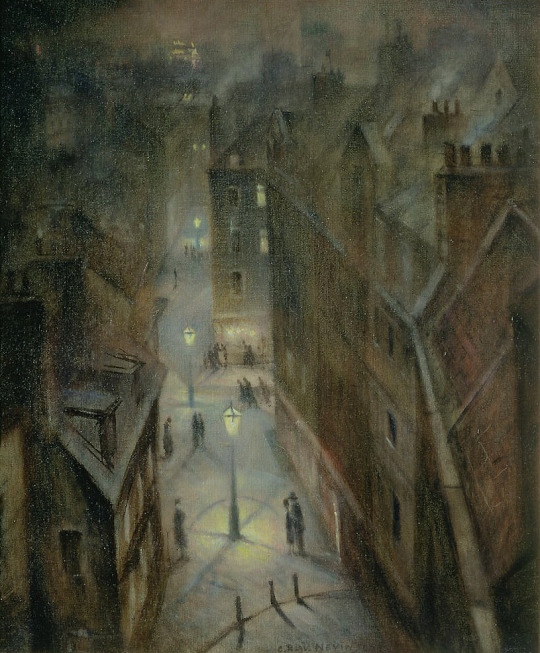

1928 "London, Winter" painting by C.R.W. Nevinson. From Art Deco, Art Nouveau & 20th Century Decoratif Arts Group, FB.

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

C.R.W. Nevinson, Studio in Montparnasse, 1926

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

C.R.W. NEVINSON

1889 - 1946

Steep Hill, Lincoln

Oil on canvas

The painting was titled Looking down the Street but the scene represented is clearly the lower part of Steep Hill in Lincoln.

See the picture at Hull University Art Collection, Brynmor Jones Library

#english imagination#english culture#albion#art#england#english art#english landscape#20th century#english countryside#english artist#hull university#Brynmor jones library#Lincoln#C R W Nevison

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Anthem for Doomed Youth' by Wilfred Owen

What passing-bells for those who die as cattle Only the monstrous anger of the guns. (Christopher Nevinson)

Only the stuttering rifles' rapid rattle Can patter out their hasty orisons (William Orpen)

No mockeries now for them; no prayers or bells Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs (Otto Dix)

The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells; And bugles calling for them from sad shires. (C.R.W. Nevinson)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

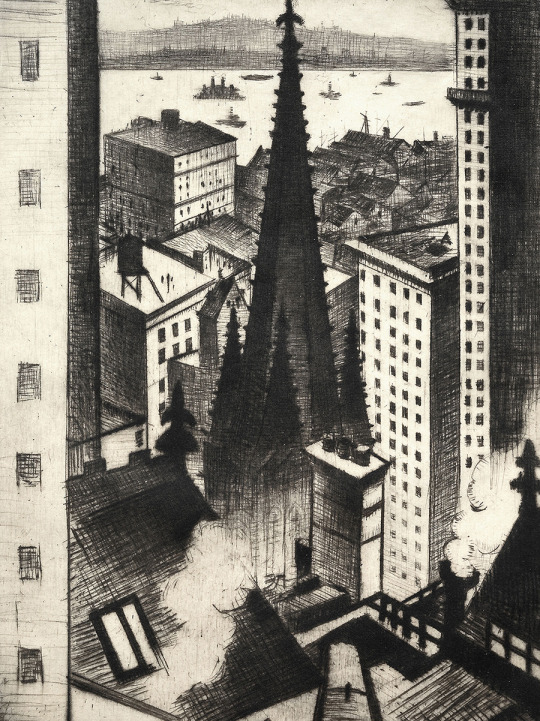

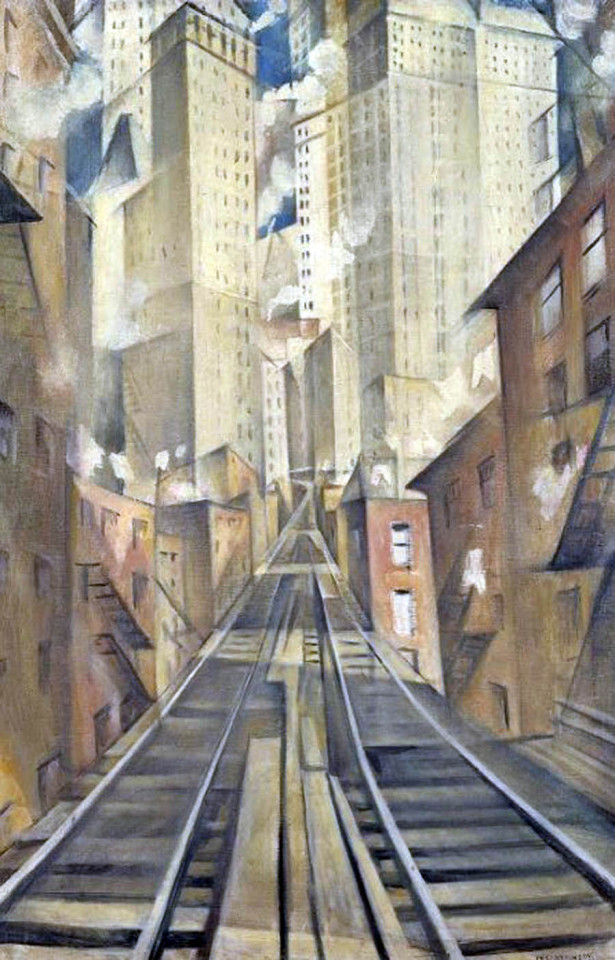

C.R.W. Nevinson, The Soul of the Soulless City, 1930.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

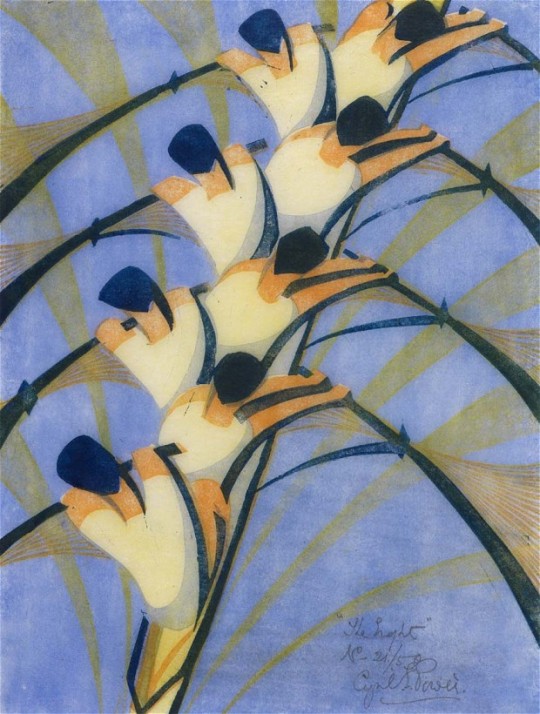

1 Cyril Power (1872-1951) UK The Eight reduction lino cut print (1930) 32.3×23.4cm

2 photographer unknown

economist.com

IT HAS become the custom nowadays,” wrote Claude Flight, a British artist, in 1926, “to go to a shop for the tools of one's trade.” Flight was scornful of shoppers and liked to make things for himself. He kept his own bees and championed the art of the linocut, believing that the use of cheap materials would help democratise art and bring it to the attention of the masses. For his own linocuts he insisted on “a sharp penknife—such a very rare thing among art students” and a gouge he fashioned by fitting a small wooden handle onto a rib he cut from an umbrella.

Hard to imagine health and safety regulations allowing children today to have such fun. But Flight, who was a friend to Henry Moore, Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth, inspired many pupils at the Grosvenor School of Modern Art, where he taught, wrote and organised exhibitions on linocuts.

Among the most famous was Cyril Power, an extraordinarily creative printmaker, born in 1872, who soaked up Flight's enthusiasms and gave them new force. Power drew on many influences—of the German Expressionists (who invented linocutting before the first world war), the Italian Futurists, the Vorticist prints and paintings of Wyndham Lewis—and the enthusiasm for speed and movement that marked the work of so many artists of the period, from Natalya Goncharova to Marcel Duchamp.

While the work of the Germans, Italians, French and Russians has become very well known, the prints and linocuts made by Power and his fellow British artists have lingered in the shadows. An inspired little exhibition—the first major show of Modernist British prints in America, which began earlier this year at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and is now at the Metropolitan Museum in New York—will help change that. So too will a newly opened show at a private gallery in London that gathers together for the first time prints of all 46 of Power's linocuts. Some are for sale; others have been lent by museums and private collectors, of which the most important are two New Yorkers, Leslie and Johanna Garfield.

The first impression of the Power show is that he lived his life in reverse. Until he was almost 50 he followed in the professional footsteps of both his father and his grandfather and practised as an architect, making a name for himself also as the author of an erudite study entitled “English Medieval Architecture”. Then, as Philip Vann explains in an elegant essay that accompanies the show, he “embarked on a kind of Gauguin-esque adventure”, leaving his wife and four children to enrol in art school in the company of a 24-year-old artist, Sybil Andrews.

The early prints in the show were made by a middle-aged man and it shows. In black-and-white there is a bridge at Rickmansworth, a street corner in the sleepy Suffolk town of Lavenham. Then suddenly the movement of the windmill in “Elmers Mill, Woolpit” gives an indication of what is to come. Starting in 1930, when he was already 58, Power takes to speed as if he had taken personal charge of the Futurist manifesto, which C.R.W. Nevinson co-signed with an incendiary Italian, Filippo Marinetti, in 1914, with the words “Forward! HURRAH for motors! HURRAH for speed!…HURRAH for lightning!”

Power allows light, noise and speed into everything he sees. Using a series of easily recognised colours, particularly “Chinese orange”, “chrome orange”, “viridian” and “Chinese blue”, he created images of merry-go-rounds, rowers, acrobats, dancers, runners, hockey players and, of course—given that some of his influences were Italian—beautiful cars.

The most successful are those, like “The Eight”, in which the element of formal design is most visible. But Power's vision as an artist really comes to the fore in works containing a hint of menace. The bourgeois-assaulting spirit of Italian Futurism, Mr Vann explains, had fallen into the malign hands of Mussolini and was about to give way to Fascism, while Freud's and Jung's obsessions with the unconscious were increasingly helping to throw up visions of fears, hopes and dreams.

“Monsignor St Thomas” (1931, pictured at left) is a brilliant working of the murder in the cathedral of Thomas à Beckett, but it is technically skilful rather than edgy. The really potent, and most modern-looking, of Power's linocuts are those that lead the viewer right to the edge. These start with “Tennis” (1933, below), a magnificent rendering not just of the energy of the centre court, but of the physical and psychological effects of slicing and spinning—sport at its most gladiatorial.

As the 1930s move towards totalitarianism and then war, Power's work takes on a darker hue. The tube trains and the escalators of the London subway system provide ample opportunity for exploring man's addiction to the rat race. Two further works seem remarkably prescient. In 1934 Power made a linocut which he called “Exam Room”, full of hunched-up concentration and a complex set of figures that show, in turn, fear, nerves, gloating, dreaming—and one who is slyly distracting a neighbour. Watching over them is the overbearing timekeeper and the all-seeing eyes in the ceiling.

Similarly, “Air Raid”, which Power made in 1935 and which has been lent to this show by the RAF Museum in Hendon, is an extraordinarily filmic response to a period of history the artist had not yet even seen. It would be another five years before the start of the Battle of Britain would make such imagery routine. Cyril Power was not just an artist, he was a visionary

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

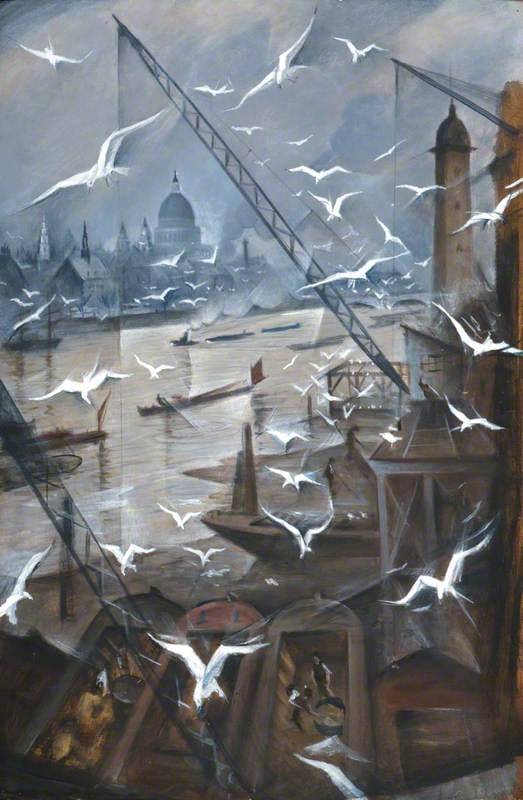

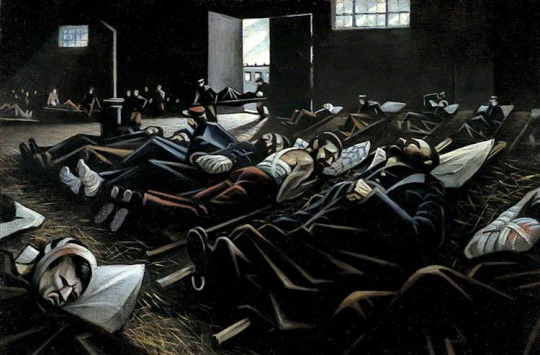

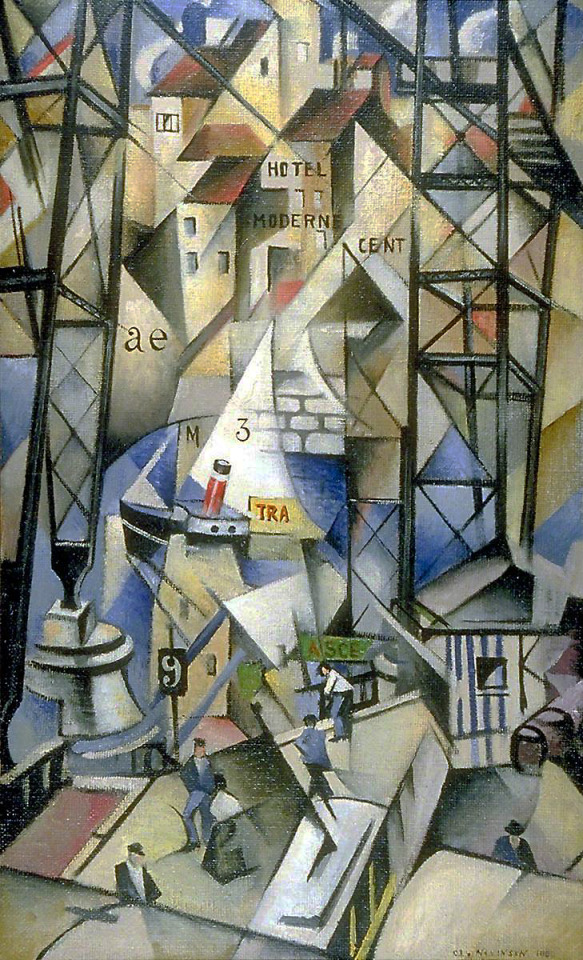

La Patrie

C.R.W. Nevinson

Fecha: 1916

Estilo: Cubismo, Expresionismo

Tema: WWI

Género: escena de género

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (British, 1889-1946), A Mule Team, between September 1917-March 1918. Oil on canvas laid on board, 25 x 30 in.

#Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson#british art#english art#c. r. w. nevinson#mules#mule team#soldier#soldiers#wwi#world war one#world war i#c.r.w. nevinson

73 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (British, 1889-1946), The Four Seasons: Spring, 1918. Oil on canvas, 61 x 50.8 cm

925 notes

·

View notes

Text

C.R.W. Nevinson.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

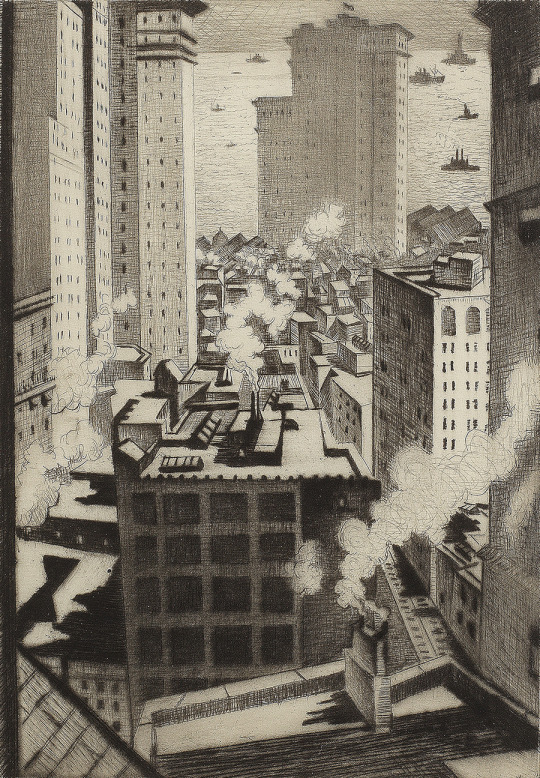

Twentieth Century by C.R.W. Nevinson (1935)

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

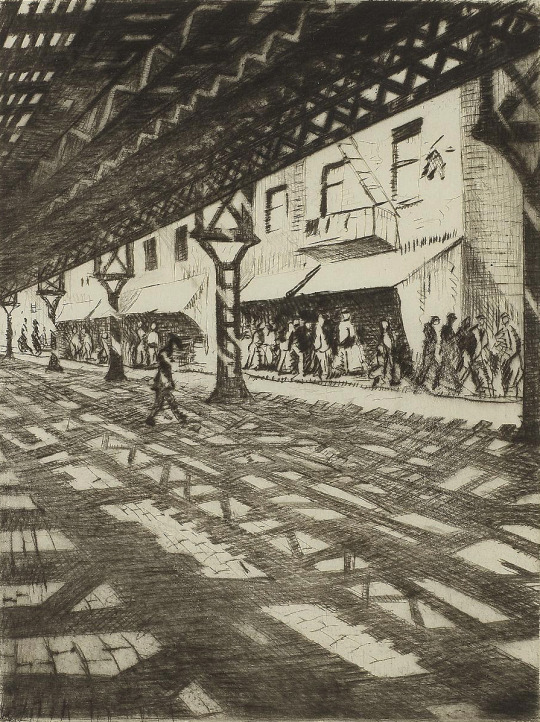

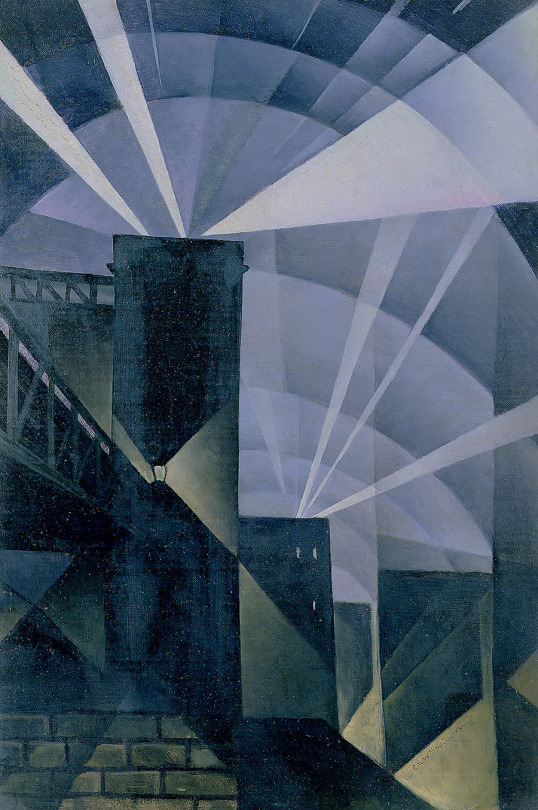

C.R.W. Nevinson, 1920. Nevinson, a British painter, first visited New York in 1919 for an exhibition of his work, which was very successful. He was very impressed with the city and, when he returned to London, painted this, which he called “New York—An Abstraction.” Later in 1920 he returned to New York for another exhibition. This one was was poorly received, and Nevinson’s attitude towards the city changed. He later changed the title of the painting to “The Soul of a Soulless City.”

From the Tate Gallery website: “The painting depicts an imaginary section of the elevated railway running through Manhattan. The image described by one American critic as “hard, metallic, unhuman” ... betrays an allegiance to Cubism and Futurism. The narrow chromatic range of mainly brown and grey and the complex facetting of the skyscrapers are closely related to Cubism. While the central motif of a railway line receding dramatically into a cluster of tower blocks epitomises a futurist interest in speed, technology and above all modernity.”

#C.R.W. Nevinson#painting#Soul of a Soulless City#New York An Abstraction#Cubism#Futurism#Tate Gallery#New York#1920#British art#elevated railroad#art

73 notes

·

View notes