#Bukharian Jewish

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Jewish recipes: Bakhsh

I often make this as a meal prep situation so I make a large dish and then we have it for lunches/dinner during the week. Or for Shabbat. This is a Bukharian Jewish dish called Bakhsh, which is a simple dish of rice that's cooked with tons of herbs, usually cilantro and dill, and with meat (most traditional is lamb iirc). I can't get kosher lamb easily where I live at all, so mine is always chicken and it's made in a glass baking dish in the oven. Bakhsh (green rice)

Ingredients:

2 cups rice (I always use short grain bc that is what we have on hand), washed/rinsed, uncooked

4 whole bunches fresh cilantro (or 3 + 1 fresh parsley -- can also add a bunch of fresh dill if desire), chopped

1 cup cubed meat of choice (I always use chicken breast), uncooked

1 diced yellow onion

1/2 c oil (I use avocado)

1/2 c water

1 tbsp salt

1 tbsp chicken consomme powder (I use the Osem brand)

Ground black pepper, cumin, turmeric, and coriander to taste

Instructions:

Line glass baking dish w/parchment paper.

Combine all ingredients in the dish, stir well. Cover with foil.

Bake covered at 400F for 45 minutes, then remove and stir well. Re-cover and bake for 45 more minutes.

Enjoy! The favorite part of this dish in my house is the brown crust that forms on bottom, similar to what we call 누룽지 (nurungji) in Korean (it's the scorched rice I guess that forms on the bottom of the stone pot) -- it's so tasty and crunchy!

#jewish food#jewish recipes#food#jumblr#jewish#recipe#bukharian jewish food#kosher#kosher food#kosher recipes

326 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey Jumblr,

What are some non-Ashknazi marriage traditions/rituals that y'all do? I was reading up on weddings and a lot of stuff (the bedeken, the walking around the groom) was written to be Ashkenazi tradition. I know a lot about henna, but that's basically it.

#jumblr#jewish#sephardi#mizrahi#maghrebi#ashkenazi#weddings#bene israel#cochin jews#kaifeng jews#yemenite#ussr jews#bukharian#italkim#romaniote

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hannah Moussaieff, a Bukharian immigrant to Ellis Island, c. 1915-1925

0 notes

Text

The embroidered textiles are called suzanis. They are found in Central Asian and particularly associated with Uzbekistan, which is where Bukhara is located. Suzanis are gorgeous, and Uzbekistan overall is known for its incredible textile production and arts! Ikat print—via fabric dying and weaving and painting—is another staple of Uzbekistan’s design style.

Bukhara has Persian roots and was a prominent center of trade, scholarship, and culture along the historic Silk Road. Even today, Tajik (a language related to Persian) remains a dominant local language, rather than Uzbek (a Turkic language).

Bukharan Jews were part of a larger group of Persian-speaking Jewish communities that also lived in modern day Iran and Afghanistan, as well as other parts of Central Asia. This was distinct from other Soviet Jewish groups in Eastern Europe, who primarily spoke Yiddish in the late 1800s and shifted to Russian in the 1900s.

Bukharan Jews are one of the oldest ethnic-religious groups in Central Asia, and their roots go back hundreds of years. Sadly, they also faced many periods of persecution.

In the 20th Century, the Soviet Union’s policies stressed assimilation and the removal of religious practice. Soviet propaganda painted all the ethnicities within the USSR as living in harmony and being equal, but this was never really the case. Central Asians—who are predominantly non-white, secular Muslims—continue to face discrimination and stereotyping even today. Antisemitism was also ever present during Soviet times, especially during the 1950s-80s.

Despite their rich history and deep roots, Bukharan Jews became more and more isolated. Many emigrated out of Central Asia to find more welcoming spaces. (Overall, Jewish out migration accelerated approaching and after the USSR collapsed in 1991.) A particularly notable community of Bukharan Jews settled in Queens in New York City. If you’re in the area, you should try to find some Uzbek food—like the textiles and art, the food is also incredible.

This was a super brief take! Here are some resources to read more:

In the former house of a wealthy Jewish merchant, Bukhara, Uzbekistan, 19th century.

#bukharan jews#uzbekistan#jewish#folk art#art#jumblr#ikat#suzani#bukharian Jews#bukhara#history stuff#Jewish emigration#rego park#queens nyc#Бухарские евреи#ussr#Central Asia

202 notes

·

View notes

Text

Celebrating Sukkot in Jerusalem 116 years Ago - Bukharian Jewish family in their sukkah - 1900

167 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you're not a queer Jew, patience is a virtue :)

313 notes

·

View notes

Text

I come from a family of enthusiastic and capable cooks, and plov was my father’s signature dish. As the child of Soviet refugees, I grew up eating many beloved dishes from Ukraine. Plov was a special-occasion meal; my father would painstakingly prepare lamb or beef, allowing it to simmer until tender before combining it with rice in a single pot. Piled onto a platter, he garnished the dish with a shower of freshly chopped cilantro — his own signature aromatic touch.

Plov is an Uzbek rice pilaf that originated in the Bukharian Jewish community. When Mizrahi Jews migrated to Central Asia during the Persian Empire, they formed a culture with their own culinary customs as well as a distinctive Persian dialect, “Bukhori.” Plov is a play on the rice pilafs of Persia, and the Bukharian dish was eventually popularized in the Russian Empire by Alexander the Great.

Plov remains a popular dish across the former Soviet Union, where there are many forms and iterations depending on the region and cook. Traditionally it’s made with lamb, carrots and onions but you’ll frequently find versions with beef or chicken, often studded with dried fruit. Like my father, I love to make plov with tender cubes of beef or lamb for special occasions. During the High Holidays, I add turmeric for a sunny hue, pops of apricot and currant for added celebratory sweetness, and an enlivening handful of chopped herbs. I finish the plov off with ample jewel-like pomegranate seeds for their tartness and joyful crimson color.

While plov involves a few steps to prepare and some time in the oven, the dish satisfyingly comes together in a single pot to form a complete meal. What emerges is aromatic golden rice with tender pieces of subtly spiced meat, along with sweet and tart bites of veggies and fruit. The play of colors and textures is a regal addition to any table, or in this case, a welcome start to a royal new year ahead.

Notes:

Plov can be made ahead of time and frozen (without garnishes). Allow the plov to fully cool, then place in freezer bags or in an airtight container. When you’re ready to serve, transfer to a foil-covered baking dish and reheat at 350°F for 40-45 minutes, or until fully warmed through. The meat will be slightly drier when reheated, but still tender. You can also reheat this in a microwave if desired.

If you prefer lamb, you can swap it for the beef sirloin in this recipe.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

It looks so good!! I'm so glad y'all enjoyed it!

Last night I made Bakhsh! It's a Bukharian rice with meat, onions, and loads of cilantro. I used the recipe from @pomegranateandhoney and it was amazing! We used lamb and increased the amount of meat in the recipe, as my family is very into meat. It turned out delicious and we enjoyed it a lot. I made a little Israeli salad to go with it.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

the shadow and bone Jewish dynamic is that mal is a mizrachi meretznik union organizer from bat yam and the darkling is an anglophone Ashkie diaspora pro-Israel stand with us organizer. Alina is half Bukharian and she and mal the only two not-ashkie kids in the Russi area they grew up in. The deus ex machina is mal getting off the plane with three double zip locked backs of hawaij for Alina and his great grandmothers wedding ketubah as final evidence in a spat they have over a storage container full of family heirlooms. The darkling has horrifically overpronounced modern Hebrew renditions of ha-Tikva and en li aretz acheret but doesn’t know who static and Ben el were or a single actual sentence mal says. Mal learned English from burned biggie and tupac tapes and got a summer job renting surfboards to tourists but promptly forgets every word of אנגלית he ever learned when cousin Alex is around and Alina has to translate everything.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bukharian Jewish women, Jerusalem

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Okay so i come from an Italian American background and I’m converting to Judaism. Having no family that even speaks Italian, is there any way for me as an Italian-American convert whose shul is multilinear but mostly Ashkenazi & Bukharian to connect with Italki identity? My family’s not even from Rome anyhow. Do you have any book recommendations on Italkim and their language?

there's a book called 'handbook of jewish languages' that has info about judeo-italian if you're interested in learning more about that language, and rabbi barbara aiello has a ton of resources about italy's jewish population! i highly recommend checking out her website. if you want some recommendations for italki traditions, consider getting a three branched shabbat candlestick! there's also a lovely tradition for havdalah where a bowl of warm rose water is passed around the table, you dip your fingers in the water, and touch them to the face of the person next to you, and it symbolizes taking the sweetness of shabbat into the next week with you. i have two italian jewish cookbooks that i love: cucina ebraica, and the classic cuisine of the italian jews. both amazing books.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

If ppl don’t stop saying stupid things I’m gonna have to put “Ashkenazi” on the confiscated words shelf

(Something about how once you don’t have any Halachic/practicing community then minhag becomes irrelevant/a personal thing and you start having stupid ideas about the nature of minhag as analogous with or mappable onto race)

It’s just the general trend of things like “well not all American Jews are white, there are non-Ashkenazi Jews in America!”

When, since minhag is transferrable via marriage, adoption, and community integration, arguably the only minhagim (whose potential practitioners are) not eligible for integration into American whiteness are מנהגי חסידות

A majority of which are… Ashkenazi minhagim

Since arguable Jewish integration into American whiteness relies on Jews not being immediately identifiable as such

In that inasmuch as Jews are seen as candidates for assimilation into whiteness, Judaism as it stands is not

And Jews are assimilateable inasmuch as they can be separated from Judaism

Cf “Frenchmen of the mosaic persuasion”

And yes, “ashkinormativity” does approximate describing an actual existing intracommunity issue in how we communicate, teach, and think (about) our histories, culture/s, practice/s, etc. as a people, and what we chose to represent as normative and how we chose to structure religious and cultural resources, especially in educating youth (what kind of siddurim do we give to children? What minhagim do we teach them in school? What kind of challah do we provide? How do we teach young people to wrap tefillin/say brachot/read torah/respond to kaddish/etc?)

but while this phenomenon is absolutely influenced/imprinted on by orientalism, it both A. Does not treat and has not historically treated all subminhagim within larger minhag “families” as equal to each other (eg Eastern European Ashkenazim being seen as backwards) and B. Is not a historically unprecedented or isolatable phenomenon within Jewish history, and many of those other examples involved other minhagim as dominating forces (see the history of Sefardi minhag wrt the Bukharian Minhag and broadly speaking the entire landscape of minhagim in the MENA region, the Syrian minhag in India, etc.)

Anyway it really feels like like some people went “is anyone going to make posts on the internet acting like this intracommunity phenomenon maps neatly onto a post-9/11 American understanding of race?” And then didn’t wait for a response before going ahead and doing that.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Calls: Iranian; Anthropological Linguistics, General Linguistics, Historical Linguistics, Language Documentation, Sociolinguistics/ Journal of Jewish Languages - "Modern Iranian Jewish Languages" (Jrnl)

Call for Papers: Modern Iranian Jewish Languages: Thematic Issue of the Journal of Jewish Languages The Iranian language family has included many Jewish languages, such as Judeo-Persian, Juhuri (Judeo-Tat), Bukharian (Judeo-Tajik), Judeo-Shirazi, Judeo-Hamedani, Judeo-Yazdi, and Judeo-Kashani. While there has been much research on medieval Judeo-Persian writing, scholarship on contemporary spoken varieties is underrepresented (see reviews in Borjian 2014, 2015; Gindin 2003; Lazard 1968; Shalem http://dlvr.it/TDm9Nr

0 notes

Text

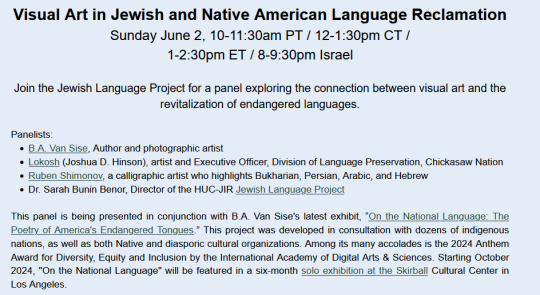

Visual Art in Jewish and Native American Language Reclamation

Sunday June 2, 10-11:30am PT / 12-1:30pm CT / 1-2:30pm ET / 8-9:30pm Israel

Join the Jewish Language Project for a panel exploring the connection between visual art and the revitalization of endangered languages.

Panelists:

B.A. Van Sise, Author and photographic artist

Lokosh (Joshua D. Hinson), artist and Executive Officer, Division of Language Preservation, Chickasaw Nation

Ruben Shimonov, a calligraphic artist who highlights Bukharian, Persian, Arabic, and Hebrew

Dr. Sarah Bunin Benor, Director of the HUC-JIR Jewish Language Project

This panel is being presented in conjunction with B.A. Van Sise's latest exhibit, “On the National Language: The Poetry of America's Endangered Tongues.” This project was developed in consultation with dozens of indigenous nations, as well as both Native and diasporic cultural organizations. Among its many accolades is the 2024 Anthem Award for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion by the International Academy of Digital Arts & Sciences. Starting October 2024, "On the National Language" will be featured in a six-month solo exhibition at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles.

Register here.

1 note

·

View note

Text

How Passover customs differ from one community to another

Passover begins on the night of 22 April, when Jews around the world sit down to the Seder, the ceremonial telling of the Exodus from Egypt. Communities follow remarkably similar customs at Passover, but there are differences, as Chabad explains. (With thanks: Leon)

Egyptian Haggadah in Hebrew and Arabic1. Avoiding Beans and Rice: While it is well known that Ashkenazim universally avoid eating beans, legumes, corn and rice on Passover (this class of food is called kitniyot), not everyone knows that many Sephardic communities keep (some or all of) this custom as well. For example, Moroccans do not eat rice but do eat beans. Conversely, some Bukharian Jews do eat rice but do not eat beans or peas.Read: Why So Many Jews Don’t Eat Beans and Rice on Passover2. Eating Soft, Chewy Matzah:It’s fascinating to note that some Sephardic communities still bake soft matzah, which is significantly thicker than the cracker-like variety that has become virtually universal in recent centuries.3. Dipping in Lemon Juice: The most common custom these days is to dip the vegetable (karpas) in saltwater. However, some Jews, such as those from Kurdistan, traditionally dip it into sour lemon juice instead!4. Passing the Afikomen: Among the Jews of the Holy Land, there is a custom to take the afikomen and wrap it in a white cloth. This is placed on the right shoulder and transferred to the left shoulder. It is thus passed around the table from one to the next, with the last one to receive it reciting the verse: “Their kneading trays were bound in cloths on their shoulders.”That person then takes four paces and is asked: “Where have you come from?” to which they respond: “From Egypt.” “And where are you going?” “To Jerusalem.”Then all raise their voices and declare together: “Next year in Jerusalem!”Read: Why Do Some People Hide the Afikomen?5. Asking the Four Questions in Arabic: There’s no getting around the fact that the Seder is essentially a conversation, with the children asking questions and the Seder leader providing the answers—which is why many people say (parts of) the Seder in Arabic, Ladino, Farsi, or even English. So if you’d been a Jewish child in Yemen or Syria a generation or two ago, in all likelihood you would have learned to say the Four Questions in Judeo-Arabic.Read: The Four Questions in Nine Languages6. Waving the Seder Plate: Those using the Haggadah as recorded by Maimonides begin with the words, Bibhilu yatzanu miMitzayim, “We left Egypt in a great hurry.” Many Moroccans have the custom of saying these words again and again, each time waving the Seder plate over the head of another person at the Seder. Only after everyone has had the Seder plate waved over their heads, do they continue with Hay lachma anya, “This is the bread of suffering … ”Read: The Passover Seder Plate7. Having the Kids Symbolically Leave Egypt: Many have the custom to give each child a bundle of matzah to drape over their shoulders and then take part in the following exchange (in Arabic):

Where are you from? From Egypt

Where are you going?

What do you carry?

Read: 14 Facts About Syrian Jews8. Watch Out for Those Scallions!

Among many Persian Jews, a favorite part of the Seder is playfully whipping each other with scallions. Why? To remember how the Jews were beaten by their Egyptian masters. Plus, it’s a great way to keep the kids awake and involved!

Read: 10 Facts About Persian Jews9. Smearing the Charoset on the Doorpost: Among some Moroccan Jews, it is customary to take some of the charoset left over after the Seder and smear it on the doorpost. It has been postulated that this is to recall the smearing of the blood on the Jewish doorposts back on the night of the Exodus (the very first Seder), as well as in anticipation of the Messianic era when, (according to the Book of Ezekiel,) sacrificial blood will be smeared on the doorway of the Holy Temple.1Read: 19 Facts About Moroccan Jews10. Announcing Moshiach to the Neighbors: If you were from Djerba, you may be accustomed to having one of your neighbors walk through the neighborhood with the afikomen tied up on his back, calling out, “Moshiach, son of David, is on his way!”May it happen soon!Read: 15 Moshiach Facts11. Gathering for Mimouna After Passover:

Moufleta pancakes and sweets at a Mimouna

After Passover concludes, Moroccan Jews hold a special celebration called mimouna. People visit each other’s homes to enjoy elaborately set tables, especially a crepe called moufleta.

The word mimouna means “luck.” On Passover, many people do not eat at each other’s homes since not everyone has the same standards. The post-Passover socialization demonstrates that there are no hard feelings.

Read article in full

44 notes

·

View notes