#Buganda king

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Namibia denies visa extension for Kabaka of Buganda amidst diplomatic tension.

Ambassador Joseph Ndawula greeting the Kabaka. Courtesy image The Namibian government has refused a request to extend the visa for a Ugandan king who has been getting medical treatment in the country since April. King Mutebi II of the Buganda has been receiving treatment for an undisclosed condition. The centre where he has been staying requested his visa extension earlier this month. But in…

0 notes

Text

✧༺┆✦The Matriarchal Societies✦┆༻✩

Matriarchal societies, where women occupy primary power roles in political, social, and economic realms, have existed across various cultures and historical periods. Distinguished by matrilineal descent, communal decision-making, and significant female authority, these societies present alternative models of social organization.

Characteristics of Matriarchal Societies

Matrilineal Descent

A hallmark of matriarchal societies is matrilineal descent. Family lineage, property, and titles are inherited through the mother’s line, ensuring continuity and stability as women control familial and economic resources. Matriarchs play central roles in family organization, often making key decisions about marriage, property distribution, and household management.

Political Authority

Women in matriarchal societies frequently hold significant political positions such as chiefs, queen mothers, or council leaders. Their leadership is active and involves governance and decision-making. Community councils, typically composed of elder women, guide community policies and resolve disputes, ensuring that women's perspectives are central to governance.

Economic Control

Women typically control property and land, managing and passing them down to their daughters. This economic power underpins their social authority and community status. They oversee the allocation of resources within the community, ensuring equitable distribution and the well-being of all members.

Cultural and Spiritual Roles

Women often serve as spiritual leaders, shamans, or priestesses, conducting important rituals and ceremonies. As custodians of spiritual knowledge and cultural traditions, women preserve and transmit cultural heritage through storytelling, education, and ritual practices, maintaining the community's identity and values.

Historical and Contemporary Examples

The Hopi (Native Americans)

The Hopi people, residing in north-eastern Arizona, follow a matrilineal system where clan membership and inheritance pass through the female line. Women own the land and homes, and they play significant roles in agricultural activities. Female elders influence decision-making processes, particularly regarding community welfare and cultural traditions.

The Ashanti (West Africa)

The Ashanti people of Ghana practice a matrilineal system in which lineage and inheritance pass through the mother's line. The Queen Mother holds significant political influence, including the authority to select the Asantehene (king). Women are key figures in trade and local markets, controlling the distribution of goods and resources.

The Baganda (Uganda)

In Buganda, a kingdom within Uganda, women hold crucial roles in the matrilineal descent system. The Namasole (queen mother) has substantial political influence and advises the Kabaka (king). Women manage household economies, control land inheritance, and are active in agricultural production, ensuring the community's sustenance.

The Mosuo (China)

Located near Lugu Lake in the Yunnan and Sichuan provinces, the Mosuo people practice a unique form of matrilineal descent. Extended families live in large households managed by the matriarch. The Mosuo have "walking marriages," where men visit their partners at night and return to their maternal homes in the morning. Children remain with their mothers, and maternal uncles play significant roles in their upbringing. Women control the household economy, manage agricultural activities, and are involved in local trade and tourism.

The Khasi (India)

The Khasi people of Meghalaya in north-eastern India follow a matrilineal system where property and family names are inherited through the female line. The youngest daughter, known as the "Ka Khadduh," inherits the ancestral property and is responsible for taking care of the elderly parents. Khasi women play central roles in household management, local commerce, and cultural rituals.

The Igbo (Nigeria)

Among the Igbo people of Nigeria, certain communities practice matrilineal descent, particularly in the inheritance of property and titles. Women are influential in trade and local markets, actively participating in community decision-making processes. Female-led organizations and associations play crucial roles in maintaining social order and cultural traditions.

The Minangkabau (Indonesia)

The Minangkabau, located in West Sumatra, are the world's largest matrilineal society. Property and family names are inherited through women. Women manage the household and family inheritance, while men handle external political relations. The role of "Bundo Kanduang" (the revered mother) symbolizes female authority and wisdom. Women play central roles in cultural ceremonies, such as weddings and funerals, reinforcing their social status and authority.

The Tuareg (Sahara Desert)

The Tuareg people, living in the Sahara Desert across Mali, Niger, Algeria, and Libya, practice matrilineal descent. Property and family tents are inherited through the female line. Women have significant autonomy and can initiate divorce. They control family wealth and manage household affairs. Women are custodians of the family's history and traditions, passing down cultural knowledge through oral traditions and music.

The Trobriand Islanders (Papua New Guinea)

The Trobriand Islanders of Papua New Guinea follow a matrilineal system where lineage and inheritance are passed through the mother’s line. Women control the distribution of yam, a staple crop that signifies wealth and social status. Female leaders, known as "dauk," play essential roles in community decision-making and cultural rituals.

The Iroquois Confederacy (North America)

The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) society, located in the north-eastern United States, is matrilineal, with clans led by elder women known as Clan Mothers. Clan Mothers have the authority to nominate and depose male leaders (sachems). They play a vital role in maintaining the Great Law of Peace, which governs the confederacy. Women are central to agricultural practices, growing the "Three Sisters" crops (corn, beans, and squash), which are crucial to the community's sustenance.

Modern Implications and Interpretations

Matriarchal societies offer models of gender equality and demonstrate that societies can thrive with women in central roles. These societies challenge the notion that patriarchal structures are necessary for social stability. The emphasis on matrilineal descent and female authority helps preserve cultural traditions, ensuring the continuity of community identity. Women's control over resources often leads to more sustainable and equitable economic practices, benefiting the community as a whole.

Challenges and Misconceptions

Common misconceptions suggest that matriarchal societies simply reverse the power dynamics of patriarchy, with women dominating men. However, these societies often emphasize balance, cooperation, and mutual respect between genders. Patriarchal societies may resist the idea of matriarchy, viewing it as a threat to established power structures, leading to the marginalization and misrepresentation of matriarchal communities.

Matriarchal societies provide valuable insights into alternative social structures where women hold central roles in political, social, and economic spheres. These societies demonstrate the viability of matrilineal and matriarchal systems, offering models for more balanced and equitable gender dynamics. Understanding these societies broadens perspectives on power distribution, gender roles, and cultural practices, challenging the dominance of patriarchal paradigms in historical and contemporary contexts. They highlight the potential for diverse forms of social organization that prioritize cooperation, sustainability, and equality.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

May 2025: Pilgrims rest along the road on their way to the annual Martyrs’ Day celebration on June 3 at the Namugongo Shrine near Kampala, Uganda.

This year, about 1 million people are expected to gather on Tuesday (June 3) to honor the 45 Christian converts — 22 Catholics and 23 Anglicans — executed between 1885 and 1887 by the orders of Buganda King Mwanga II for refusing to renounce their faith.

(Photo by Tonny Onyulo)

#religion#christianity#catholicism#anglican#christians#people#pilgrimage#martyrs day#uganda#divinum-pacis

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Kasubi Tombs - A Living UNESCO World Heritage Site

The Kasubi Tombs in Kampala, Uganda, is the site of the burial grounds for four kabakas (kings of Buganda) and other members of the Baganda royal family. As a result, the site remains an important spiritual and political site for the Ganda people, as well as an important example of traditional architecture. It became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in December 2001,[1] when it was described as “one…

#African Great Lakes#east african architecture#east african history#Kasubi Tombs#Republic of Uganda#The Kasubi Tombs#Uganda

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

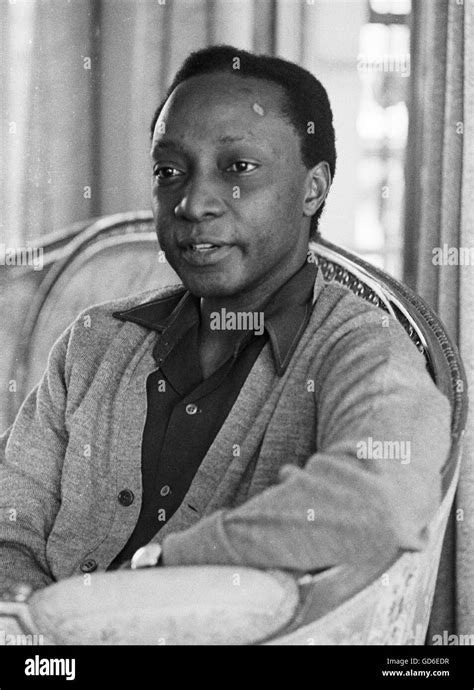

Ssekabaka Daudi Chwa II, or King Daudi (August 8, 1896 - November 22, 1939) was born in Mengo Hill to the last independent ruler of Buganda, Kabaka Danieri Basammula-Ekkere Mwanga II, and his wife, Evaliini Kulabako of the Ngabi clan. He entered the world during the early days of British colonization in Buganda when European imperialism threatened African traditions, lifestyles, religious practices, and freedom.

He assumed the throne in August of 1897. His age at the time of his coronation necessitated the constant authority of regents to govern on his behalf, which included prime ministers Apollo Kaggwa, Tefero Kisosonkoke, Nsibirwa, and Samual Sebagereka. He inherited religious upheavals and colonial oppression, his experience differed from his father’s; the young ruler never knew a life free of land untouched by colonial control.

He received an education from Kings College Buddo. When he turned 18 years old, he was finally able to assume the full responsibilities of kabaka (king). The British Army granted him lieutenant status which he held for three years until September 22, 1917, when he was appointed an honorary captain for the British army. He was awarded the title of Commander of the Order of the Crown of Belgium. On February 16, 1925, he was promoted to Knight Commander and was later awarded an additional honorary title of Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1937. Most accounts describe him as a “fair, responsible, and pragmatic” king. The titles received from the British make him the most decorated Buganda king, albeit they were awarded by colonial overlords who ruled what was now the British colony of Uganda. Little has been recorded regarding his personal feelings towards the British during his rule.

He had seventeen wives with whom he fathered thirty-six children: sixteen daughters and twenty sons. His son, Edward Muteesa, succeeded him and reigned until his exile in 1955, where he remained until Uganda’s independence in 1962. He returned to become the first president of Uganda post-independence. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Being Gay is African: A Historical Perspective

The assertion that homosexuality is a Western concept is a myth largely propagated by colonial influences and the import of Christianity. Historically, African cultures have recognized and included various forms of same-sex relationships and identities, which have only been obscured by later colonial and religious narratives.

Contemporary Conflicts and Historical Evidence

During his visit to Africa in 2015, US President Barack Obama highlighted the legal discrimination against LGBT individuals. In Kenya, he emphasized the importance of treating all individuals equally, irrespective of their differences. Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta responded by asserting that Kenyan culture does not accept homosexuality. This sentiment is not unique and has been echoed by other African leaders such as Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe, Goodluck Jonathan of Nigeria, and Yoweri Museveni of Uganda. However, historical evidence contradicts these assertions.

Historical Examples of Homosexuality in Africa

Ancient and Pre-Colonial Evidence

Yoruba Language: The Yoruba language has a term, "adofuro," which describes someone who engages in anal sex. This term, which predates colonial influence, indicates an awareness of homosexual behavior.

Azande Warriors: In the 19th century, the Azande people of Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo practiced same-sex relationships where warriors would marry young men due to the scarcity of women. These relationships were socially accepted and included rituals and formal marriage customs (Face2Face Africa).

King Mwanga II of Buganda: King Mwanga II of Uganda openly engaged in homosexual relationships with his male servants before the advent of Christian missionaries who brought condemnation (JSTOR Daily).

Ancient Egypt: Paintings and records suggest that Nyankh-Khnum and Knum-Hotep, royal servants in ancient Egypt, may have had a homosexual relationship. These men were depicted in affectionate poses and shared a tomb, highlighting the acceptance of their relationship within their society (AfricaOTR).

Meru Community in Kenya: The Mugawe, religious leaders among the Meru, often dressed in women's clothes and married men. This role was not just accepted but integrated into the spiritual and social fabric of the community (AfricaOTR).

Anthropological Insights

Marc Epprecht, a historian, documents various forms of same-sex relationships across Africa that were ignored or misinterpreted by early Western anthropologists. These relationships ranged from love affairs to ritualistic practices. For example, among the Imbangala of Angola, same-sex relationships were part of ritual magic. Similarly, in South Africa, temporary "mine marriages" were formed among men working in mines during colonial times (JSTOR Daily).

The Influence of Christianity and Colonialism

The rise of fundamental Christianity, heavily influenced by American televangelists since the 1980s, has significantly shaped the contemporary African stance on homosexuality. Many Africans argue that homosexuality is against Biblical teachings, yet the Bible itself is not part of African historical culture. This adoption of a Western religious framework to argue against homosexuality demonstrates a significant cultural shift influenced by colonialism.

The Political Use of Homophobia

Populist homophobia has become a political tool in many African countries. Politicians gain votes by promoting anti-gay sentiments, creating an environment where hatred and violence against LGBT individuals are not only accepted but encouraged. This has led to severe consequences, such as corrective rapes in South Africa and oppressive laws across the continent.

Reclaiming African Heritage

To combat the dangerous narrative that homosexuality is un-African, it is crucial to retell and reclaim African history. African culture historically celebrated diversity and promoted acceptance, including various sexual orientations and gender identities. By acknowledging and teaching this true history, we can foster a more inclusive and equitable society.

Reaffirming our commitment to historical accuracy and cultural inclusivity is essential. True African heritage is one of acceptance and recognition of all its members, regardless of their sexuality.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Back in Uganda again - 10 years later

Stepping off the plane in Entebbe, I was surprised how familiar everything still feels. The air smells the same, the accents tickle the ear the same way, the shops are brightly painted with the same paints. To be back somewhere after nearly ten years is such a blessing. I often find myself thinking about how much has changed since 2015--I now have a bachelor, a masters, and a new citizenship, I survived a global pandemic, I moved to Vienna (twice)--but I also marvel at how much is the same. Returning to Red Chilli, the same hotel where my Ugandan adventure began last time brought a special sort of nostalgia.

But last time I was here, I missed out on touring Kampala. So this time, I was determined not to make the same mistake twice. I set off bright and early on a city tour of Uganda's capital. We started with a tour of the Old Taxi Park, where you can catch a ride to anywhere in Uganda--and some places even farther than that. Following the taxi park, we did a quick jaunt through the Okiwano Market, the biggest market in the city.

After, we made our way up Old Kampala Hill to the Gaddafi National Mosque. The mosque sits on top of the tallest hill in the city, where the British first built their colonial capital. The mosque was first begun by Idi Amin but was not completed before he was ousted in 1979. The mosque remained incomplete until 2002, when Gaddafi visited Kampala and pledged to finish the project. The mosque is built with wood from the Congo, carpets from Turkey, lamps from Egypt and art from Saudi Arabia. After the tour of the interior, we walked up the 292 steps (woof) of the minaret to see the best view of Kampala; from the top, you can see the city stadium, the first Anglican church and the first Catholic church in the city, and the Makerere University campus.

Next, we traveled to Kabaka Palace, where the kings of Buganda Kingdom used to live. The palace was built in the late 1880s and housed three Bugandan kings before it was commandeered by Idi Amin's forces in the 70s. The palace armory then became the scene of torture and execution for thousands of innocent Ugandans. The guide told me to take a picture of the torture chamber, though I have not included it here, so that I could "remember the horrors of that time."

After perhaps the most depressing part of the tour, we went to lunch. For lunch, we stopped at a small local restaurant called Maama Barbarou, where we feasted on rice, brands, beef stew, yams and more to fortify us before our final stop.

Last, but not least, we visited the Martyr's Shrine, which was built at the site where the 32 first Christians in Uganda were killed for their faith in the late 1800s. The church is magnificent, built in a circular shape to resemble a traditional African home, the interior made of magnificent mahogany wood. On the 3rd of June every year, the area is overtaken by over one million pilgrims, many of whom walk from their homes in Uganda, Rwanda, Kenya, Tanzánia and Burundi. While I was visiting, the guide showed me the exact spot where the martyrs were burned alive, which is now where the church's alter sits. Outside, there is a large amphitheater, which was filled with pilgrims celebrating their faith.

Though the tour of Kampala was a little depressing, I am glad they I got to bettet understand the city and her people before heading to my next location.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

You may not think of Uganda when one mentions LGBTQIA+, but did you know the country has/had a fair amount of cultural gender diversity history & other LGBTQIA+ adjacent history? Before colonialism, there were several cultures which had various types of fluid, diverse & trans-adjacent genders & expressions, aswell as less restrictive sexualities like those of western society:

Mudoko Dako: In Langi, Teso & Karamoja society, Feminine AMAB individuals seen & treated as women, and is seen as a (?) third gender (?)

Okule (Lugbara: AMAB Individuals who embody the feminine & female and are often spiritual mediums, healers, & other spiritual roles

Agule (Lugbara :AFAB individuals who embody the masculine & male and are often spiritual mediums, healers, & other spiritual roles

Bunyoro people: Described historically as having "men who crossdressed"

Mwanga II of Buganda: King of Buganda born in 1868 known to have been bisexual. It generally seems as if the people of Buganda were fairly neutral when it came to gay stuff

The Kiga or Abakiga people are also said to have or have had lesbian relationships.

To name a few.

This is the history and livelihood that colonialism stole from what can be inferred as thousands of cultures, and now it's somehow "wrong"? The same happened to my home country of Finland when they tried to take it away from the Sami people... This above and more that is now lost to history existed for thousands of years! But if we keep fighting, the LGBTQIA+ history of everyone's country will be seen & loved again 🌺

"Response from President Museveni has been defiant – suggesting that calls to repeal the anti-homosexuality law as a western imposition. “Western countries should stop wasting the time of humanity by trying to impose their practices on other people” he says... Totally ignorant on Uganda's history and bending to colonialist "social purity" and conformity that isn't theirs.

In 2023 a law was signed in Uganda which made life for gay & trans people harder than ever... Today, many are in refugee camps and the media doesn't talk about it.

#lgbt history#trans history#trans rights#Gay rights#uganda#Uganda lgbtqia+#Uganda lgbt#Lgbt uganda#Uganda trans#Trans uganda#Trans culture#Gay culture#Transgender history#lgbtqi#trans#trans pride#gender history#human rights#lgbtqi history

1 note

·

View note

Text

St. Kizito being baptised by St. Charles Lwanga at Munyonyo,

Stained glass at Munyonyo Martyrs Shrine,

Saint Charles Lwanga and his Companions were a group of twenty-two Catholic martyrs, killed for their faith in Uganda between 1885 and 1887. They were part of a wider persecution of Christian converts (both Catholic and Anglican) under the rule of King Mwanga II of Buganda. The king, fearing the growing influence of Christianity in his court and angered by its opposition to his immoral demands, especially toward young male pages, began a brutal campaign against the Christian converts. Charles Lwanga, a court official and a devout Catholic, courageously protected the younger boys from the king’s abuses and continued to instruct them in the faith, even after the murder of the Catholic missionary Joseph Mukasa Balikuddembe.

On 3 June 1886, Charles and twelve of his companions were burned alive at Namugongo, having refused to renounce their faith. Their martyrdom became a powerful witness, inspiring the growth of Christianity throughout Uganda and beyond. Pope Paul VI canonised them in 1964, recognising not only their heroic virtue but also the extraordinary witness of a young, indigenous African Church. Today's feast holds special significance in Africa, especially in Uganda, where they are national heroes and spiritual intercessors.

Among those martyred was Saint Kizito, the youngest of the group, who was just 14 years old at the time of his death. Our stained glass window from the Munyonyo Martyrs Shrine. A page at the royal court, Kizito was deeply influenced by the example and care of Charles Lwanga. On the night before their execution, at Munyonyo, Charles secretly baptised Kizito, knowing that their deaths were imminent. It was an act of immense courage and love, a final gift of faith from one saint to another! That moment, in the darkness of persecution, symbolises the light of Christ passed from one soul to another, and the enduring strength of belief in the face of terror. Today, Munyonyo is a place of pilgrimage, where the memory of their sacrifice continues to inspire generations of believers.

by Father Patrick van der Vorst

0 notes

Text

The mysterious disappearance of the Buganda Kingdom's royal regalia is a significant historical enigma that combines elements of colonial history, cultural heritage, and political intrigue. The Buganda Kingdom, located in modern-day Uganda, was one of the most powerful and influential of the traditional kingdoms in East Africa. Its royal regalia, consisting of sacred drums, spears, shields, and the royal mace, held immense cultural and spiritual significance, symbolizing the legitimacy and authority of the Kabaka (king). #BugandaRegaliaMystery #LostRoyalTreasures #BugandaKingdomLegacy #CulturalHeritageEnigma #EastAfricanHistory #SacredRoyalArtifacts #KabakaSymbolism #ColonialEraSecrets #HistoricalIntrigue #UgandaMysteries Disclaimer: This video contains certain footage and images generated using AI technology. These AI generated visuals have been used where original or real footage of individuals or events was unavailable. We have ensured that all AI-created content accurately reflects the subject matter and maintains the highest level of respect for the individuals and events discussed. Any historical facts or information presented in this video have been carefully researched and verified from reliable sources. The use of AI is intended solely for illustrative purposes and should not be interpreted as a representation of actual persons or events unless otherwise stated. Section 107 of the Copyright Act 1976: Reference: https://bit.ly/3l8GUbc 1) This video has no negative impact. 2) This video is also for entertainment purposes. 3) It is transformative in nature. Where is the Lost Royal Regalia of Buganda? A Hidden or Stolen Tragedy published first on https://www.youtube.com/@bafflingmysteries/

#Unsolved Crime Mysteries#Alien Encounters Investigations#Unexplained Phenomena Explained#Mysterious Disappearances Unraveled#Enigmatic Historical Events

0 notes

Text

Heading: King Freddie of Buganda: A Hard Lesson in Friendship and Power

I remember it clearly: sometime in the mid-seventies, while studying at Eton College, I stumbled upon a British newspaper story that left me chilled to the bone. It was about Sir Edward Frederick Mutesa II, known to many as “King Freddie” of Buganda. Born on 19 November 1924 and crowned as the Kabaka of Buganda in 1939, he had once moved effortlessly through the corridors of British high society. Knighted by Queen Elizabeth II, commissioned as an officer in the Grenadier Guards, he was a man who could walk into any exclusive London club and command immediate respect. Later, as the first President of independent Uganda (from 9 October 1963 to 2 March 1966), he seemed destined for lasting greatness.

But by the late 1960s, after a violent fallout with then-Prime Minister Milton Obote, King Freddie was forced to flee Uganda. He slipped into exile in London in 1966, no longer a toast of empire but a man living in obscurity and near-poverty. He died there on 21 November 1969 in a modest flat in Rotherhithe—reduced to near anonymity, abandoned by the very British elites who had once embraced him.

I was just seventeen when I read this. The lesson hit me like a hammer to the chest: friendships forged in the glow of power can vanish the moment the lights go out. As I sat in that hot Eton dining hall, surrounded by faces I assumed were my friends, I wondered if I too might one day be cast aside. If the currency of my worth ever depreciated, would those who hovered near suddenly vanish into the London fog, just as they had for King Freddie?

Back then, Nigeria in the 1970s was thriving—thanks to the oil boom, champagne seemed to flow like water, and American and European businessmen were thick on the ground in Lagos. Around 1974, one Nigerian Naira fetched about US$1.52, a currency so respected you barely needed visas for travel across Europe. Our passports opened doors, not raised eyebrows. No one whispered “scam” or “fraud” when they heard where we came from. We were the new kids on the global block, courted, wined, and dined. It felt like it would never end.

Today, of course, that golden era seems like a lifetime ago. The Nigerian economy buckled under mismanagement, and the Naira’s strength evaporated. Reputations got dragged through the mud. The so-called friends once clamoring around me have long since faded into silence. Is it simply physical distance—or is it the stench of lost leverage, no longer granting me a seat at their table?

No, I’m not naïve. I’m not heartbroken. King Freddie’s fate was my early warning. He taught me that when your worth to others is measured by your utility, their devotion is conditional and fleeting. He was once a gilded figure in British society—yet died in exile, half-forgotten and wholly abandoned. His life was a cautionary tale I’ve carried with me ever since, a reminder that true friendship is not founded on power, position, or currency. It endures or fails on the strength of human character alone.

#KingFreddie #Buganda #UgandaHistory #BritishColonialism #EtonMemories #Nigeria1970s #LostAllies #FriendshipAndPower #ExileStories #HistoryLessons

0 notes

Text

Unesco removes Ugandan kings' tombs from endangered heritage list

On Tuesday, Unesco removed the Kasubi site, home to the tombs of the rulers of Buganda, the traditional kingdom of southern Uganda, from the list of World Heritage in Danger after it was damaged by fire in 2010. Located in the hills above the capital Kampala, this complex of circular buildings made of wood, reeds and thatched roofs has been listed as a World Heritage Site by the United Nations…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

DAILY SCRIPTURE READINGS (DSR) 📚 Group, Tue Dec 10th, 2024 ... Tuesday Of The Second Week Of Advent, Year C ... THE HOLY UGANDA MARTYRS WINDOW

UGANDA MARTYRS: UNYIELDING FAITH

The Church marks the Feast of the Uganda Martyrs on June 03rd, a day that in Uganda is a national holiday.

WHO WERE THESE MARTYRS, AND WHAT IS THEIR STORY?

It is one with a remarkable relevance for today. These martyrs were boys in their teens, and they died for their Christian faith—and, more especifically, because they refused to take part in homosexual activities. For their commitment to their faith and to its clear moral teachings, these 22 boys died in a particularly horrific manner: they were killed in all brutal ways but above all, burned alive.

Today, Catholics have to stand with courage when speaking about homosexuality. To affirm the Church’s teaching is to invite ridicule and insults—and, increasingly, to face legal difficulties. In Britain for instance, new legislation has forced Catholic adoption agencies to choose between closure and agreeing to offer children to homosexual couples. A Catholic broadcaster received a visit from the police after she spoke against homosexual adoption on a radio program—she was warned that she might have committed a “homophobic” offense.

Years ago the Church published a document (signed by then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger) that affirmed its teaching on homosexuality and offered some details concerning the pastoral care of people with homosexual tendencies. The date chosen for the announcement was June 3: the feast of the Uganda Martyrs.

FAITH EMBRACED —AND REJECTED

The story of the heroic young Uganda martyrs begins with the arrival in the late 1880s of European missionaries, both Anglican and Catholic, in the territory then known as Buganda. They found a local culture and community that was warmly open to the Christian message and to news and information from the wider world. But as Christianity began to permeate local life, tensions arose. The ruler, the Kabaka, died, and his son and heir to the throne inherited the reigns of power. This new ruler, King Mwanga, a dissolute and spoilt youth, felt threatened by the vigor and openness of mind shown by the young pages at his court who had converted to Christianity. Chief among these was Charles Lwanga, a tall and handsome youth who was a natural leader, excelling in sports and hunting. He was also one whose life of prayer and evident integrity influenced his fellows and drew them to ask questions about what inspired him.

Fear of the political and military intentions of the European powers—especially Britain—also played a part in what was to come. A visiting Anglican missionary, Bishop James Hannington, was murdered on the orders of the Kabaka. Dying with courage and dignity, he showed a faith that impressed the local people. After his death one of King Mwanga’s subjects, Joseph Mukasa Balikuddembe, rebuked the king. For his audacious courage to defend life, he was savagely beheaded. A wave of persecution was just beginning.

In the martyrdom that followed, boys who had become Christians—Catholic and Anglican—found their faith tested to its keenest limits. The Catholics had been attending prayers and catechism classes with the missionaries. Some had been baptized; others were still under instruction. A separate group of boys had for some while been attending the Anglican mission and had been baptized there. The atmosphere at court had been profoundly affected by all of this: the example of both Anglicans and Catholics influenced palace members and others in the Kingdom and beyond.

A THWARTED KING ’S FURY

Initially, the young Kabaka also had been impressed by Christianity: he liked what he saw and heard of the Christian message, and he also recognized that his people would benefit from the education and skills that the missionaries had brought with them. Moreover, guns, gun gunpowder, and other gifts from the missionaries attracted and enabled him project power and that of his kingdom. But this was not enough to counter his other, stronger, commitment—to a dissolute lifestyle, and especially to witchcraft and homosexual activities to which he had become increasingly addicted.

After some weeks of tension, which stretched over Eastertide, the young men at court sensed that a major drama was about to unfold. One afternoon, after an unsuccessful day’s hunt on lake Victoria, King Mwanga sent for Mwafu, his favourite page boy, whom he wanted to engage in homosexual gratification. The boy could not be found, and the king, in a rage, started to shout about the disloyalty and insolence he found at court. He knew that the boy’s absence was almost certainly due to Christians diverting him to their activities so that he would not have to face the Kabaka’s advances. He knew it was likely the boy had absented himself because he was hiding away from his engagement. Rounding up the boys known to be the keenest Christians, he ranted and hurled insults at them. He also demanded that they give up their ways of prayer and return to unstinting obedience to him in all things.

It became clear in the days that followed that homosexual activity and willingness to comply with immorality were the heart of the matter—the Kabaka’s rage had been fueled by the increasing reluctance of his young Christian subjects to indulge him in this. Death was the punishment for opposing the whims and wishes of this absolute sovereign.

But the boys stood firm. Arrested and bound, with ropes cutting into their wrists and feet, they prayed and sang hymns. The older boys, especially Charles Lwanga, taught and encouraged the younger ones, notably Kizito. The youngest of all, Kizito was just 14, and alternated between radiant enthusiasm for Christ and a shaking fear of the death that now awaited them.

DEATH TO “THOSE WHO PRAY”

The tribal ritual surrounding executions was grim. As the boys watched it begin, it must have struck terror into their hearts. The executioners, dressed in leopard skins and with their faces painted white in traditional designs, wove in long dances as they wailed a chant while the victims watched: “The mothers of these will weep today—O yes, they will weep today.”

Had any of the boys agreed to abandon their prayers and obey the Kabaka, their lives would have been saved. The Kabaka specifically referred to the Christian boys as “those who pray.” Any who chose to leave that category and renounce their Christian faith could walk back into favor with the ruler.

Namugongo, the site for executions, was a 16km distance from the Kabaka’s Munyonyo court that was at Victoria lake shore, and the journey there took several days. For some of the boys, tight shackles made walking difficult and a number were executed along the way. Those who arrived at Namugongo were crammed into prison huts within the locality of their execution. This was done to buy time for executioners to cut sufficient firewood and build the great funeral pyre upon which the Christians would be burned alive.

On the day of execution, June 3rd 1886, Charles Lwanga was separated from the main group and burnt on a lone pyre slightly over a kilometre before the main pyre where all the rest of Catholic and Anglican pages were burnt. Already bound and ready for burning, Charles Lwanga surprised his executioner whom he asked to untie him so he could lay well his own pyre. With unparalleled courage, he was placed back on the pyre and burnt slowly from toe to head. It's on this very spot of his martyrdom that today an Altar stands in a Shrine built and consecrated a minor Basilica. This Catholic Shrine has been visited by three Popes (St Paul VI in 1969, St John Paul II in 1993, and Pope Francis in 2015).

The many eyewitnesses to the martyrdom (the boys were killed in front of a large crowd of their own family members and friends) left a detailed account of the events.

This execution of Uganda Martyrs reads rather like the early martyrdoms of Christians in pagan Rome. Extraordinary scenes transpired. The boys prayed and sang hymns as they were rolled and tied in reed matting and dragged to the fire. Young Kizito is said to have gone to his martyrdom singing and calling out that soon he would meet Christ in paradise. As the flames were lit, the prayers did not stop. The young boys’ voices could be heard, clear and unafraid, as the fire crackled up to meet them.

When all was over, mounds of burnt wood and ashes remained, to become one day the rallying base of a great shrine which is now visited by millions of people annually. Every year, on June 3, vast crowds arrive for an open-air Mass. Children are given the day off school. Kizito is a popular name for boys in Uganda and beyond, and his story is told to First Communion and confirmation groups.

AN URGENT WITNESS TODAY

The Ugandan Martyrs were formally canonized in 1964, the first time that African drums were used in a ceremony at St. Peter’s in Rome. The emergence of Africa as a new stronghold of Christianity, the ecumenical dimension, the proximity of all this to the Second Vatican Council which was opening up a new chapter in the Church’s history—all gave the canonization a special sense of historic importance. But at that time no one thought to remark on the moral teachings at the center of it all: that the martyrs had witnessed with their lives to the truth that sexual communion is reserved to men and women in the lifelong bond of marriage and that homosexual activity is gravely sinful. In 1964, that was simply taken for granted by Anglicans and Catholics alike.

Today, however, we see the boys’ martyrdom as having an extra dimension of significance precisely because of this truth and their courageous witness to it. God speaks to us poignantly through the heroism of these youths. Their witness calls us to join them in courage and faith. We have been given their example at a time when we all need it.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church, affirming unchanging truths of the Catholic faith for a new century, quotes Scripture and Tradition in describing homosexual acts as intrinsically disordered and contrary to the moral law. It calls for respect, compassion, and sensitivity towards those who—like the young Kabaka—struggle with homosexual tendencies and calls them to chastity and Christian perfection. The Catechism also hails martyrdom as “the supreme witness given to the truth of the faith: it means bearing witness even unto death” (CCC 2473). The Catechism notes “The Church has painstakingly collected the records of those who persevered to the end in witnessing to their faith. These are the acts of the martyrs. They form the archives of truth written in letters of blood” (2474).

TWO CHURCHES, ONE MARTYRDOM

A most touching aspect to this story of martyrdom is that both Catholic and Anglican boys were caught up in this drama. The Catholic Church does not presume to impose its forms of canonization on those who are not members—but in the ceremony in Rome which was to write the Ugandan Martyrs into the Church’s calendar, special mention with honor was made of the boys of the Anglican Communion who met their deaths—and whose names, incidentally, are recorded on a great memorial in the Anglican Cathedral in Uganda’s capital.

**

VICARIATE APOSTOLIC OF UPPER NILE

Vicariate Apostolic of Upper Nile, separated from the mission of Nyanza, July 6, 1894, comprises the eastern portion of Uganda, that is roughly east of a line from Fauvera on the Nile (about 2° 13′ N. lat.), northeast to the Kaffa mountains, and of a line south from Fauvera past Munyonyo near Lake Victoria Nyanza to 1° S. lat. Of the native tribes, the Baganda, the largest ethnic tribe, accessed formal education before others. Their religion was spiritualistic, acknowledging a Divine Providence, Katonda, who, being good, was neglected, while the loubalis, or demon, and mizimus, or departed souls, were propitiated. Totemism was prevalent, the amaziro, or totem, being usually an animal, rarely a plant. The first Catholic missionaries, the White Fathers, arrived in Uganda in 1878. Father Lourdel obtained leave from King Mutesa to enter; on June 26, 1879, the fathers reached Rubaga.

On Easter Saturday, March 27, 1880, the first catechumens were baptized; two years later the Arabs induced Mutesa to expel the missionaries; they returned under his successor, Mwanga, July 14, 1885. Religion spread rapidly, but the Protestants and Arabs stirred up the king to begin a persecution. Joseph Mukasa, chief of the royal pages, was the proto-martyr; on May 26, 1886, thirty newly baptized Catholics, on refusing to apostatize, were burnt to death; soon more than seventy others were martyred. Then the Arabs plotted to depose Mwanga, but the Catholics by the advice of Father Lourdel remained loyal. The Arabs thereupon expelled the missionaries, who, however, returned in 1889: Father Lourdel endeavored to induce Mwanga to submit to the advancing British Company; on May 12, 1890, worn out by his labors this pioneer of the Gospel died. His confreres continued to reap a rich harvest, but were opposed by Captain Lugard, the British Company’s agent. On May 23, 1893, Uganda passed under the protection of the British Government and the Church gained comparative peace. Msgr. Livinhac, now Superior General of the White Fathers, obtained the erection of the eastern portion of Uganda into a separate vicariate under the care of the English congregation of Foreign Missions, Mill Hill, London.

The first vicar Apostolic was Msgr. Henry Hanlon, b. on January 7, 1862, consecrated titular Bishop of Teos in 1894, went to Uganda in 1895; after laboring there for seventeen years, he returned to England for the general chapter of his Society, and retired from active missionary work. He was succeeded (June, 1912) by Msgr. John Biermans, titular Bishop of Gargara. Coming to Uganda in 1896 he proved himself a valuable auxiliary to Msgr. Hanlon. The episcopal residence is at Mengo, Buganda, near Entebbe, capital (then) of Uganda. In the mission there were 24 priests, 6 Missionary Franciscan Sisters of Mary; 15 churches; 12 schools with 1649 pupils; and about 20,000 Catholics. The missionaries have recently compiled and printed in Uganda, a grammar, phrasebook, and vocabulary of a Nilotic language, Dho Levo, spoken in Kavirondo. The language had not previously been reduced to writing. Some primers, catechisms, and prayerbooks also in Dho Levo have been printed.

**

VICARIATE APOSTOLIC OF NORTHERN VICTORIA NYANZA

The Mission of Victoria Nyanza, founded in 1878 by the White Fathers of Cardinal Lavigerie, was erected into a vicariate Apostolic May 31, 1883, with Msgr. Livinhac as the first vicar Apostolic. When the latter was raised to the superior-generalship of the Society of White Fathers (October, 1889), the Holy See appointed Msgr. Hirth as his successor. A Decree of July 6, 1894, divided Victoria Nyanza into three autonomous missions: that of Southern Nyanza in the German Protectorate, of which Msgr. Hirth retained the government and became the first titular; those of the Upper Nile and Northern Nyanza, in English territory, the former given to the Fathers of Mill Hill and the second to the White Fathers. From the 18 provinces of Uganda the Decree of 1894 detached that of Kyaggive and Kampala Mengo, which it placed under the jurisdiction of the Fathers of Mill Hill, and gave to Northern Nyanza the remaining 17 provinces of the Kingdom of Uganda, the three Kingdoms of Bunyoro, Toro, and Ankole, and in the Belgian Congo an isosceles triangle whose top was the northern point of Lake Albert Nyanza and whose base followed the 30th degree of longitude. Three races share the portion of Northern Nyanza lying in the English protectorate; the first, that of the Baganda, is represented by 670,000 inhabitants, and has given the strongest support to evangelization, and in 1886 had the courage and the honor to give to the Church its first negro martyrs. The second race, the Banyoro, is represented by 520,000 aborigines; the third, the Bahima (Hamites), the leading class in the shepherd Kingdom of Ankole, is in a minority not exceeding 50,000 souls. The total population of Northern Nyanza equals therefore about 1,500,000 inhabitants, of whom 1,400,000 are in English territory, and 360,000 in the Congo country.

At the time of its creation (July, 1894) Northern Nyanza had an administrator, 17 missionaries divided among 5 stations, 15,000 neophytes and 21,000 catechumens. In July, 1896, the date of the death of Msgr. Guillerman, the first vicar Apostolic, the vicariate had 6 stations, 21 missionaries, and 20,000 baptized Christians. In July, 1911, it had 1 bishop, Msgr. Henri Streicher (preconized February 2, 1897), Bishop of Tabarca and second vicar Apostolic of Southern Nyanza, 118 missionaries divided among 28 stations, 113,810 neophytes and 97,630 catechumens. All the missionaries of Northern Nyanza, including the vicar Apostolic, are members of the Society of White Fathers founded by Cardinal Lavigerie. As yet the native clergy consists only of 2 subdeacons, 4 minor clerics, and 4 tonsured clerics. They are assisted by 28 European religious of the Society of White Sisters, and by an institute of native religious called the Daughters of Mary. Eleven hundred and five Baganda and Banyoro teachers cooperate in the educational work and in the service of 832 churches or chapels. The Vicariate of Northern Nyanza has 894 scholastic establishments, viz. a lower seminary with 80 students, and upper seminary with 16 students in philosophy and theology, a high school with 45 pupils, most of them the sons of chiefs, a normal school with 62 boarders, and 890 primary schools in which free instruction is given to 19,157 pupils, of whom 11,244 are boys and 7913 girls. The annual report of the vicar Apostolic from June, 1910, to June, 1911, shows 7930 confirmations, 1154 marriages, 578,657 confessions heard, 1,236,126 communions administered, and the gratuitous distribution of 394,495 remedies. The headquarters of the mission is at Villa Maria, near Masaka, Uganda. There are situated the residence of the bishop, the two seminaries, a flourishing mission station, the central house of the White Sisters, the novitiate of the native sisters, and a printing establishment where there is published monthly in the Luganda language an interesting 16-page magazine entitled “Munno”, which has 2000 native subscribers. Entebbe is the seat of the procurator of the vicariate.

***

Compiled and slightly edited from Catholic sources by #CharlesOngoleJohn

【Build your Faith in Christ Jesus on #dailyscripturereadingsgroup 📚: +256 751 540 524 .. Whatsapp】

0 notes

Text

May 2025: A young woman displays a crucifix during her pilgrimage to the Namugongo Shrine, near Kampala, Uganda.

This year, about 1 million people are expected to gather on Tuesday (June 3) to honor the 45 Christian converts — 22 Catholics and 23 Anglicans — executed between 1885 and 1887 by the orders of Buganda King Mwanga II for refusing to renounce their faith. (Photo by Tonny Onyulo)

#religion#christianity#catholicism#anglican#christians#women#people#pilgrimage#martyrs day#uganda#divinum-pacis

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 11.30 (before 1960)

978 – Franco-German war of 978–980: Holy Roman Emperor Otto II lifts the siege of Paris and withdraws. 1707 – Queen Anne's War: The second Siege of Pensacola comes to end with the failure of the British Empire and their Creek allies to capture Pensacola, Spanish Florida. 1718 – Great Northern War: King Charles XII of Sweden dies during a siege of the fortress of Fredriksten in Norway. 1782 – American Revolutionary War: Treaty of Paris: In Paris, representatives from the United States and Great Britain sign preliminary peace articles (later formalized as the 1783 Treaty of Paris). 1786 – The Grand Duchy of Tuscany, under Pietro Leopoldo I, becomes the first modern state to abolish the death penalty (later commemorated as Cities for Life Day). 1803 – The Balmis Expedition starts in Spain with the aim of vaccinating millions against smallpox in Spanish America and Philippines. 1803 – In New Orleans, Spanish representatives officially transfer the Louisiana Territory to the French First Republic. 1853 – Crimean War: Battle of Sinop: The Imperial Russian Navy under Pavel Nakhimov destroys the Ottoman fleet under Osman Pasha at Sinop, a sea port in northern Turkey. 1864 – American Civil War: The Confederate Army of Tennessee suffers heavy losses in an attack on the Union Army of the Ohio in the Battle of Franklin. 1872 – The first-ever international football match takes place at Hamilton Crescent, Glasgow, between Scotland and England. 1916 – Costa Rica signs the Buenos Aires Convention, a copyright treaty. 1936 – In London, the Crystal Palace is destroyed by fire. 1939 – World War II: The Soviet Red Army crosses the Finnish border in several places and bomb Helsinki and several other Finnish cities, starting the Winter War. 1940 – World War II: Signing of the Sino-Japanese Treaty of 1940 between the Empire of Japan and the newly formed Wang Jingwei-led Reorganized National Government of the Republic of China. This treaty was considered so unfair to China that it was compared to the Twenty-One Demands. 1941 – The Holocaust: The SS-Einsatzgruppen round up roughly 25,000 Jews from the Riga Ghetto and kill them in the Rumbula massacre. 1942 – World War II: Battle of Tassafaronga; A smaller squadron of Imperial Japanese Navy destroyers led by Raizō Tanaka defeats a U.S. Navy cruiser force under Carleton H. Wright. 1947 – Civil War in Mandatory Palestine begins, leading up to the creation of the State of Israel and the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. 1953 – Edward Mutesa II, the kabaka (king) of Buganda is deposed and exiled to London by Sir Andrew Cohen, Governor of Uganda. 1954 – In Sylacauga, Alabama, United States, the Hodges meteorite crashes through a roof and hits a woman taking an afternoon nap; this is the only documented case in the Western Hemisphere of a human being hit by a rock from space.

0 notes

Text

Buganda Royals Remember Kabaka Muteesa II 55 Years Later

(Kampala) – On Tuesday, November 26, 2024, members of the Buganda Kingdom, including royals and government officials, gathered at Lubaga Cathedral in Kampala to commemorate the life and legacy of Kabaka Edward Muteesa II. The memorial Mass, held in honor of the late king, marked the 55th anniversary of his death. The Holy Mass was led by Archbishop Paul Ssemwogerere, and the service was attended…

0 notes