#Brain 🧠 | Features | Psychology | Science 🧫 🧬 🧪

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

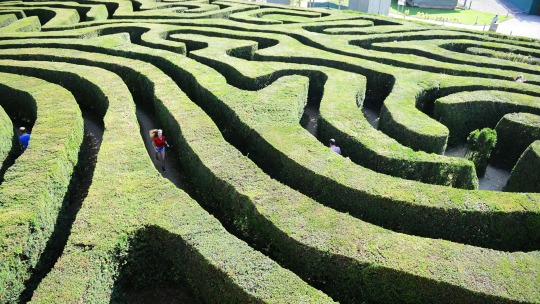

How To Improve Your Sense Of Direction

— By Christine Ro | February 18, 2024

A Young Girl Navigating Hampton Court Maze in 2009. Credit: Getty Images

Some people can strike off on any journey with no guide except their 'Pigeon Senses'. How do they do it? And can this ability be learned?

Ralph Street loves maps. Appropriately for someone with his surname, he studied geography and town planning. And well before that, his parents regularly took him out orienteering – a sport that involves racing between two points using a topographical map and a compass.

"I don't really remember a time before orienteering," Street reflects. "My parents took me orienteering the first week I was born."

Street refers to this as free training, as he now competes internationally as an orienteer, from his home base of Oslo in Norway. But these elite skills have also been useful in everyday life. Street remembers a childhood trip from London to Glasgow, with friends who deferred to him as they realised his knack for getting around the new city. In general, he tries to be diplomatic when he has a difference of opinion with another person about the correct way to go. "I'm usually right, but… we might do their thing first and [then] realise they're wrong."

Other orienteers also report better spatial memory than average. But competitive orienteers have an unusual amount of navigation practice. In fact, the latest neuroscience and psychology research suggests that there are plenty of ways for ordinary people to improve their spatial skills.

Why Some People are Better at Getting Around

Street took up the sport of orienteering at the age of nine. As his experiences suggest, childhood exposure shapes people's comfort and confidence with navigation. Kids having the opportunity to move independently around varied environments matters here. "Experiments with non-human animals suggest that passive motion is not that good because you don't basically pay attention," says Nora Newcombe, a psychology professor at Temple University in Philadelphia.

People who grew up outside cities, or in more spatially complex cities (think Prague rather than Chicago), also appear to be better able to navigate as adults. This is related to the distances travelled and the variety of areas traversed.

Even as adults, "we do have good evidence that people who range more widely around their environment" have better spatial skills, says Newcombe. Going straight back and forth between the home and the workplace doesn't cut it.

In many societies, girls and women have limited opportunities to practice their navigation skills, and this is thought to be a key reason for the myth that women are innately worse at navigation than men. Women sometimes consider themselves to be worse navigators than men even in studies where their performance is the same, due partly to gendered stereotypes. (Older men are the group most likely to overestimate their navigation abilities.)

Overall, gender inequality is associated with gendered differences in navigation ability. This points to the role of culture in creating such differences (or the perception of such differences). "People tend to overestimate the effect of gender, and also they tend to assume that the effect of gender is somehow independent of cultural factors," says Pablo Fernandez-Velasco, a philosopher and cognitive scientist at the University of York and University College London.

One Way Scientists Can Test a Person's Sense of Direction is Using a Kind of Virtual Maze. Credit: Getty Images

Indeed, anthropology research suggests that in more gender-egalitarian societies, gender differences in navigation ability vanish. One relevant study, from 2019, concerns the Mbendjele BaYaka people in the Republic of Congo, who hunt and gather food in the rainforest without using tools like maps or compasses. Research participants were very accurate overall in tests of pointing accuracy, with no differences between men and women. The scientists attributed this to the similar distances travelled (and spatial experience gained) by women and men in this society.

Haneul Jang, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, recalls one yam foraging trip with a BaYaka woman, when the two wandered off from the main group and ended up in the middle of nowhere in the forest. Jang's Global Positioning System GPS was unable to help find trails, but her BaYaka companion "immediately looked up, checked the sun and started to walk in one direction, and soon after we found a trail".

Gender also has a cultural influence on whether girls are steered toward certain occupations where navigation is critical. Through pointing and model-building tests, Newcombe's research has found that experienced geologists have higher navigational competence than experienced psychologists. This link to the fields of science, technology, engineering and medicine (Stem) chimes with what Street has noticed in his own community: that many orienteers end up in fields like engineering, maths and physics. (He himself works in IT.)

Related to the effect of education are income and privilege, and global research suggests that a nation's GDP per capita is linked to average navigation ability.

How Brains Handle Navigation

How does all this get processed in the brain? One element is cognitive maps, which are essentially mental models of space. Researchers continue to debate what shape cognitive maps take: for instance, whether humans create representations of maps in their brains to navigate, or if they are graphs.

"The map view basically says that there's an overall common framework that we're trying to fit new information into. And the graph view says, well, we can't really even do that unless the new information is attached to some node in the graph," says Newcombe. This may seem like a very academic distinction, but "it influences our view of whether or not people can combine local spaces and can infer new routes that they have very little information about," she explains.

The cognitive map is believed to reside in the hippocampus, a seahorse-shaped region of the brain involved in memory. Neuroscience research has shown that the structures around the hippocampus also play key roles in orientation. For instance, the entorhinal region has been described as the site of the "goal direction signal".

Using Aids Such as Maps May Lead to a Dependence on Navigational Help. Credit: Getty Images

Along with knowing which direction you're facing and the direction of your destination, being able to identify permanent landmarks is implicated in good navigation. This ability to recognise stable landmarks has been linked to activity in the retrosplenial cortex, which forms part of the wrinkly outer layer of the brain.

The brains of highly skilled navigators look different to those of others. One of the best-known examples comes from London cab drivers, who take years to acquire what's reverentially referred to as "The Knowledge". These cabbies' brains show growth in the hippocampus.

Though there are various orientation and direction tests, there's no gold-standard psychology test of navigation skills, especially across cultures. There are major research gaps in how certain cultures view and pass on information about navigation, let alone how those skills might be assessed in some sort of standardised way.

"The traditional [test] is something like a virtual maze," says Fernandez-Velasco, which isn't necessarily adapted to how wayfinding works in different environments and cultures. For instance, while Western navigation tends to privilege visual cues, certain other cultures are more attentive to cues based on smell, hearing, or other senses. "It's hard to capture all of this with the same test, especially with the same test that tends to be very biased towards what we consider good navigation in the Western context and perhaps in the urban context."

To improve the state of knowledge overall – as well as to help preserve types of navigational knowledge at risk of fading away, such as wave piloting in the Marshall Islands – Fernandez-Velasco says there are important questions for navigation research around "how to engage with local collaborators" and "consider non-colonial knowledge systems".

How to Become a Better Navigator

Misconceptions abound about human navigation. "One myth is that you think you cannot improve," Newcombe says. Fernandez-Velasco agrees: while their brains show less plasticity, adults can definitely still learn these skills.

Newcombe is also bothered by people considering navigation abilities irrelevant in the era of GPS. Phone batteries can die and systems can make mistakes, as suggested by accounts of people driving into bodies of water on the advice of their GPS.

Navigational aids like maps, compasses, rock art and stick charts are types of 'cognitive artefacts' – useful in many cases, but they can lead to a dependence. "Sometimes when you're using a cognitive artefact, you're offloading your cognitive abilities to that cognitive artefact," Fernandez-Velasco says of GPS, especially. "That itself might have some negative effect on your ability for navigating over time."

People can train themselves to better notice environmental cues like the wind, Sun and slopes, whether they're in rural or urban settings. "There are cues that a lot of people don't pay attention to," Newcombe says. Pursuits like sailing and scouting can help. Street encourages people to join their local orienteering club.

Not everyone will have the resources or opportunities to participate in these kinds of activities, but some principles can be put into practice while simply walking or wheeling around. For one thing, getting better at navigation requires changing our relationship with risk. "A lot of people aren't willing to explore because they're afraid," Newcombe says. "Lots of adults have quite a lot of spatial anxiety. Basically, they don't want to waste time, but also they are afraid that something bad will happen."

People Who Spend More Time Exploring Their Environment Tend to be Better at Navigating. Credit: Alamy

In a vicious cycle, that anxiety can worsen navigation, as anxiety takes up the mental space needed for spatial tasks. "If you make people anxious in the lab, their ability to navigate seems to deteriorate," says Newcombe. Yet where safe to do, getting lost occasionally serves our sense of direction overall.

While cultural variation makes it difficult to provide universal tips for improving navigation, in general, "the more you move, especially in ways that are slightly challenging, the better you'll become at navigation," Fernandez-Velasco says. "Part of the problem is that people who are bad at navigation sometimes are unconfident and avoid situations that involve navigation, so there could be this negative feedback."

For people who can't imagine wayfinding without a phone app, there are still ways to exercise spatial skills with this tech. Don't let Google Maps always decide your route, Street says.

Change the settings where possible, Newcombe suggests. The default on many apps is that "wherever you're going is straight ahead, which is a terrible way to learn. I totally advocate keeping north on the top all the time." As well, "keep zooming in and zooming out so you can both see the fine-grained information you need to navigate, but also see the landmarks."

Getting an optimal amount of sleep may help too. One global study found that for participants aged 54 and older, sleeping seven hours a night was linked to the best performance in a navigation game.

So while an orienteer in Norway and a forager in the Republic of Congo might have different ways of getting around their environments, the good news is that they – and you – can continue to hone these skills over a lifetime.

0 notes