#Bourriaud

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

“I’m more interested in looking for something transitory than in producing a conclusion.”

Pierre Huyghe

“I’m interested in contingency,” the French artist Pierre Huyghe has said. “Of what is not predictable. Of what is unknown. I think that has somehow been a core of my work.”1 Pursuing interests in contingency and unpredictability, Huyghe creates art forms that incorporate living organisms, such as dogs, turtles, spiders, peacocks, ants, and bees. Over the course of an exhibition, his living works of art grow, decay, and die. Huyghe said, “They are not made for us. They are not made to be looked at. They exist in themselves.”2

Throughout his career, Huyghe has experimented with many mediums and technologies, including film, sculpture, photography, music, and living ecosystems. At the outset of his career, Huyghe collaborated with artists whose work explored human relations and their social context; to describe their interests, the curator and art critic Nicolas Bourriaud coined the term Relational Aesthetics. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Huyghe’s works often reenacted notable artworks or popular footage from mass media. In Silence Score (English Version), a musical notation of John Cage’s pivotal composition 4'33", he created a readable score for the silent piece using a computer algorithm.

In 1997, with artists Charles de Meaux, Philippe Parreno, and Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster and curators Xavier Douroux and Franck Gautherot, Huyghe cofounded a film production company called Anna Sanders Films. They named the company after a fictional character first developed in a magazine released in 1997. Blanche-Neige Lucie, the company’s first film, stars Lucie Doléne, the voice actor who dubbed the Disney character Snow White in French, and who won a lawsuit against the Walt Disney Corporation for the rights to the reproduction of her voice. The film features Doléne humming the melody of “Someday My Prince Will Come” in an empty film studio, facing the camera, while her story is told through the subtitles. The work explores how a voice can be used to create a character, and who then owns that product.

The Host and The Cloud fuses scripted action and improvised narratives generated by the actors. The yearlong project records theatrical events that took place in an abandoned museum in Paris on three holidays: the Day of the Dead, Valentine’s Day, and May Day. In a variety of fictional settings, 15 actors clad in LED masks perform alongside puppets and animation. These spontaneous elements reflect Huyghe’s interest in contingency and adding dynamic layers to his storylines.

Originally created for Documenta 13 in 2012, Huyghe’s Untilled (Liegender Frauenakt) is a reclining female nude whose head is covered by a live beehive. The work was part of an entire ecological system the artist created in a composting area in Karlsaue Park in Kassel, Germany. In a video Huyghe filmed during the exhibition, his camera captured a wide range of beings at different scales, including minute species that are barely visible to the naked eye. Huyghe aims to “intensify the presence of things, to find its own particular presentation, its own appearance and its own life, rather than subjecting it to pre-established models.”3 With interest in “the transitory state, in the in-between,” his complex worlds blur the boundaries between the natural and the artificial, the physical and the virtual, and the real and the fictional.4 In 2015 and again in 2023, the statue found itself in MoMA’s Sculpture Garden, placed in a new context and in conversation with other works of art. During the summer, the bees travel in and out of the garden to pollinate and build their hive.

Huyghe’s artistic practice reflects his belief that life is in constant flux, and that all beings exist beyond the perceivable realm of human senses and knowledge. By engaging with unconventional materials and technologies, he provides us with a way to see, feel, and experience the wild, untilled world we are living in.

Source: MoMA / Pic: YBCA

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

of course there are women that are like that too but i just attented a nicolas bourriaud lecture and i got this confirmation when he had to answers questions: he just could not remove himself from the art critic position. and sometimes conversation with lovers are like this: they just don’t want want to be real with you

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE EVENS ARTS PRIZE 2023

Exploring the critical imaginaries of AI The Evens Arts Prize 2023 is dedicated to artistic practices that challenge prevailing systems of knowledge and experiments new alliances between living beings and machines.

The Jury is composed of Daniel Blanga Gubbay, Artistic Co-Director, Kunstenfestivaldesarts; Nicolas Bourriaud, Artistic Director, 15th Gwangju Biennale; Elena Filipovic, Director and Curator, Kunsthalle Basel; Matteo Pasquinelli, Associate Professor in Philosophy of Science, Ca’ Foscari University; Gosia Plysa, Director, Unsound. The Jury Chair is André Wilkens, Director, European Cultural Foundation. Artistic Director: Anne Davidian, curator.

Focus of the Evens Arts Prize 2023 The widespread use of AI applications, particularly in the form of text-to-image generators and large language models, has sparked intense scrutiny and debate. These discussions, fueled by both excitement about their potential and concerns about their biases, bring to the forefront crucial questions about human subjectivity, autonomy, and agency.

Technical systems are deeply intertwined with social systems, shaping our lived experiences, aspirations, and politics. Together with artists, how can we better understand and address the impact of AI and the broader constellation of digital technologies and algorithmic politics? What new imaginaries and alliances can we cultivate between living beings and machines?

The new edition of the Evens Arts Prize seeks to highlight artistic projects that explore alternative cosmologies and epistemologies, question human exceptionalism, and shed light on issues such as surveillance, manipulation, extractivism, digital governance, justice, care, and responsibility in the age of machine intelligence. Of particular interest are practices that experiment with AI to challenge prevailing systems of knowledge and power asymmetries, mobilise technologies towards emancipatory community outcomes, and envision democratic futures.

The laureate is selected by an independent jury from a list of nominations put forward by representatives of major European cultural institutions.

The Nominators of the Evens Arts Prize 2023 Ramon Amaro, Senior Researcher in Digital Culture, Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam; Zdenka Badovinac, Director, Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb; Lars Bang Larsen, Head of Art & Research, Art Hub, Copenhagen; Leonardo Bigazzi, Curator, Foundation In Between Art Films, Rome; Mercedes Bunz, Professor Digital Culture & Humanities, King's College, London; Francesca Corona, Artistic Director, Festival d'Automne, Paris; Julia Eckhardt, Artistic Director, Q-02, Brussels; Silvia Fanti, Artistic Director, Live Arts Week /Xing, Bologna; iLiana Fokianaki, Founder, State of Concept, Athens; Cyrus Goberville, Head of Cultural Programming, Bourse de Commerce | Pinault Collection, Paris; Stefanie Hessler, Director, Swiss Institute, New York; Mathilde Henrot, Programmer, Locarno Film Festival; Nora N. Khan & Andrea Bellini, Artistic Directors, Biennale Image en Mouvement 2024, Geneva; Peter Kirn, Director, MusicMakers HackLab, CTM Festival, Berlin; Inga Lace, Curator, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, Riga; Andrea Lissoni, Director, Haus der Kunst, Munich; Frank Madlener, Director, IRCAM, Paris; Anna Manubens, Director, Hangar, Barcelona; Anne Hilde Neset, Director, Henie Onstad, Høvikodden; Nóra Ó Murchú, Artistic Director, transmediale, Berlin; Maria Ines Rodriguez, Director, Walter Leblanc Foundation, Brussels; Nadim Samman, Curator for the Digital Sphere, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin; Andras Siebold, Artistic Director, Kampnagel, Hamburg; Caspar Sonnen, Head of New Media, International Documentary Film Festival (IDFA), Amsterdam; Marlies Wirth, Curator for Digital Arts, MAK, Vienna; Ben Vickers, Curator, Publisher, CTO, Serpentine Galleries, London.

The Evens Arts Prize The Evens Arts Prize honours artists who engage with contemporary challenges in Europe and shape inspirational visions for our common world. Far from reducing artistic practice to a function – whether a social balm or a political catalyst – the Evens Arts Prize supports aesthetically and intellectually powerful work that pushes the understanding of alterity, difference, and plurality in new directions, questions values and narratives, creates space for silenced or dissonant voices, and reflects on diverse forms of togetherness and belonging.

The biennial Prize is awarded to a European artist working in the fields of visual or performing arts, including cinema, theater, dance, music; it carries a sum of €15,000. The laureates are selected by an independent jury, from a list of internationally acclaimed artists, nominated by representatives of major European cultural institutions.

The 2011, 2019 and 2021 editions were curated by Anne Davidian and celebrated Marlene Monteiro Freitas, Eszter Salamon, and Sven Augustijnen as laureates of the main prize, while Eliane Radigue and Andrea Büttner received the Special Mention of the Jury.

More about the Prize

📷 from Atlas of Anomalous AI, edited by Ben Vickers and K Allado-McDowell, Ignota Books, 2020

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I bought the book Postproduction by Nicolas Bourriaud bc I kept seeing it cited in webpages on collage and appropriative art, and already I'm like Oh He Gets It

Very excited to keep reading :D

#salem chatter#oughhhh assemblage and collage not as appropriation but sharing#the tie to museums is really good

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Museum: A New Social Sculpture" by Simon Wu in Spike Art Magazine 75 Spring 2023

Some have called this the "reparative turn," which has called on institutions to atone for current and historical grievances perpetrated by museums and society more broadly. Writing about documenta fifteen, curated by the Indonesian collective ruangrupa, New York Times art critic Jason Farago described how the show "militated against its own viewing," focusing on work-shops, social gatherings, and "vibing" over visual art: "The real work of the show was not the stuff on the walls but the hanging out around it." Farago continued that this was connected to a larger shift away from aesthetics and toward various forms of social practice observable in museums, art schools, and magazines. Similarly, art historian Barry Schwabsky, writing in 2022 for The Nation, described the recession of the "aesthetic regime," or a turn away from art as a matter of form to increasingly privilege its ethical content. "What if today we are witnessing a return to a time when art is valued for its social utility, its edifying effect on the viewer," he wrote, "more than for its aesthetic valence?"

[...] In 1996, the curator Nicolas Bourriaud coined the term "relational aesthetics" to describe a growing tendency among practitioners to use social scenarios as materials for their art. There were temporary bars (Jorge Pardo's at K21, Dusseldorf; Michael Lin's at Palais de Tokyo, Paris; Liam Gillick's at Whitechapel Gallery, London), reading lounges (Apolonija Sustersi's at Kustverein Munchen, or the changing "Le Salon" program at Palais de Tokyo), and pad thai (Rirkrit Tiravanija's Untitled 1992 (Free) at 303 Gallery in New York), all of which used social situations as readymade performances of sorts. Throughout the 2000s, artists like Thomas Hirschhorn, Tania Bruguera, and Theaster Gates expanded these ideas into sprawling, multi-year projects that came to resemble libraries and community centers. From its inception, relational aesthetics inspired fierce debates over the relationships between utility, art, and civic duty. What did it mean to assess and experience that verged on social services according to ethical as well as aesthetic metrics?

Perhaps we have come to see the museum itself as a big, unwieldy project of relational aesthetics. When I go to a museum now, I want to know: Who sits on the board? What are their investments? Is the staff trying to unionize? What are its ties to both police and local communities? To think of the museum as a kind of collaborative social performance is to imbue its operations with both formal mutability and symbolic potential, positioning all those involved as "artists" engaged in its collective reshaping. This is not to just say that the museum is a work of art, or that it can escape the criticism that "good ethics" make for "bad art" endemic to relational aesthetics. It is more to say that perhaps those aspects that always felt concrete and immovable are feeling more unmoored than ever.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

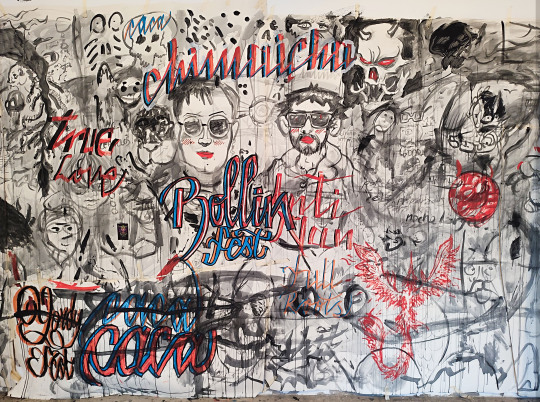

Social

Presentación

'Social' es un proyecto artístico que consiste en la generación de un proceso colectivo de creación pictórica contemporáneo ideado y gestionado por los artistas Intiñan y Carloz. Los autores entienden a la pintura como un espacio de encuentro, unión, alegría y de transformación social. La acción colectiva, referenciada en la teoría de una estética relacional (Bourriaud), enfatiza las interacciones humanas y su contexto social por sobre las acciones individuales y privadas. La apertura de su proceso lo asemeja al lenguaje mural o la naturaleza de la urbe, donde la pintura se presenta como una experiencia de intercambio entre sus integrantes y la disolución de sus individualidades.

La finalidad del proyecto es generar dinámicas artísticas de creación y flujo colectivo que escapen de la cotidianeidad dentro de un contexto que, por lo general, entiende a la pintura como un proceso individual o privado; y a las relaciones sociales dentro de los parámetros comerciales de las redes sociales. Para los gestores no existe una distinción entre arte y vida, sino una linealidad constante entre uno y otra que la obra refleja como un lugar de coincidencia, pero también de disputa, en donde las libertades personales colisionan y se retroalimentan para formar una imagen impredecible (regulada en si misma por las personas y el contexto en las que fue creada). La dinámica generada sería una especie de antena que captura determinados puntos de aquella linealidad, no para representarla, sino para descubrir posibles caminos inexplorados de relaciones sociales múltiples y viables.

“Porque el modernismo está inmerso en un “imaginario de oposiciones”, retomando la expresión de Gilbert Durand, que actuaba separando y oponiendo, descalificando de buena gana el pasado y valorando el futuro; se basaba en el conflicto, mientras que en el imaginario de nuestra época se preocupa por las negociaciones, por las uniones, por lo que coexiste. Ya no se busca hoy progresar a través de opuestos y conflictos, sino inventar nuevos conjuntos, relaciones posibles entre unidades diferenciadas, construcciones de alianzas entre diferentes actores. Los contratos estéticos y los contratos sociales son así: nadie pretende volver a la edad de oro en la Tierra y sólo se pretende crear modus vivendi que posibiliten relaciones sociales justas, modos de vida más densos, combinaciones de existencia múltiples y fecundas. Y el arte ya no busca representar utopías, sino construir espacios concretos.”*

Metodología

Es simple en sus formas, el comando es de expresión libre y está determinada por las influencias del contexto sobre los participantes. Los autores facilitan los materiales y el estímulo para que los participantes se atrevan a pintar (muchas veces se encuentra reticencia en algunos participantes resultados de prejuicios acerca del concepto de lo que significa saber pintar/dibujar). El soporte es papel tabaco** de grandes dimensiones que recubren el entorno arquitectónico. El desarrollo de la obra se extiende por varias sesiones con diferentes actores. Dependiendo del caso, la actividad termina con la saturación del área del papel y la superposición de varias capas traslucidas de pintura. El tiempo está determinado por los artistas y la convivencia entre la obra y los autores. No existe una direccionalidad definida en la forma. El comando artístico es simple y los resultados indeterminados. Al final se registran los nombres de las personas involucradas en la creación durante el proceso.

*Estética relacional, Nicolas Bourriaud, pag. 54-55

**Material de uso comercial que se haya con ese nombre en la zona del mercado central de Lima. Es vendido por metros y tiene un ancho de 1.60 m aproximadamente.

Carloz, Lima, octubre 2023.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I found these readings to be very interesting, especially considering the fact that we are entering our final projects on post production and appropriation. I think Bourriaud did a fantastic job of explaining this new way of viewing art and how in his words, “it is no longer a matter of starting with a “blank slate” or creating meaning on the basis of virgin material but of finding a means of intersection into the innumerable flows of production”. This idea of artists working with the material that is already around them is conflicting in my eyes. After reading both articles I found my self wrestling with this idea of appropriation because to me part of art is the originality and creativity of it, the genesis of something new. However, then I argued to myself, an artist who curates and creates something new with existing material has also demonstrated a form of talent and creativity as well so I don’t think there is a straightforward, clear view on this idea of appropriation. This idea reminded me of how oftentimes musical artists get frustrated with the fact that another artist used similar rhythms or pitches in their songs and claim them as stolen. This image I shared is of rapper Vanilla ice next to a picture of Freddy Murcury because I thought about the time he was actually sued for the similarities between Vanilla Ices’ song Ice Ice Baby and Queen’s song Under Pressure. Even in this situation I feel conflicted because I see no distinct way to draw a line between using someone else’s material for art vs considering it copyright because according to Gergel, material today is seen more as “collective cultural property”. One thing that was a consistent throughine in the two pieces was the fact that we are in a new digital age which is part of the growth of art being curated out of preexisting material, because now more than ever material is so accesible. Bourriaud’s question that he leaves with the reader of “why wouldn’t the meaning of a work have as much to do with the use one makes of it as with the artist’s intentions for it?” reminded me of death of the author and the fact that once an artist releases something it is almost in essence “out of their hands” how it gets interpreted for further use and development and subjects their work to the power of the consumer which was really something to consider.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bourriaud and Gergel readings assigned this week really made me think about ownership and copyright within art and other industries. It became apparent to me that the way that industries view what is considered copyright varies significantly. For example, the Gergel reading discusses Richard Prince, who controversially took screenshots of public account’s Instagram posts and printed them out for profit without their consent or significant alteration to the images. This has been seen as controversial. Yet, in the music industry artists commonly “sample” music from other songs. This is most commonly done in the rap industry. In fact, some sub genres of music within EDM are entirely dedicated to only using prior created music.

But if we were to compare this to writing this would be an entirely different story. I am writing this post after several other people in my class have already submitted their responses to Tumblr. If I were to copy and paste the response of my classmate, but I changed the font color and added a funny catch phrase at the bottom I would likely be given a stern warning. If I did it again, I might even be sent to the Office of Community Standards and if I continued to do so I could be suspended from the school. But in artistry, there seems to be a gray area for this. From my observations, it appears that the industry tends to favor the “copier” rather than the “original creator.” While some theorists like Bourriaud argue that, “The material they manipulate is no longer primary,” artists like Richard Prince are still able to profit and gain notoriety off of their work (Bourriaud, 7). There are few repercussions within the industry to regulate this.

Thinking about this more I realized the issue in the art industry. Rap music is able to get away with sampling music because it is done openly and rappers rarely claim a sample as their own. In my example of writing a response above, I could be exempt from any honor code violation if I were to cite my source properly. So long as I do not claim the work to be mine and I correctly name the original creator, then society seems to almost always deem this as okay. I think that this is where art needs to draw the line. Consent and citations are critical for the “reproduction” of art to be ethical. Gergel underscores the former aspect and points out that, “while copyright law concerns the rights of the owner, what about the rights of the subject?” Art has not only offered little protections for creators but also has failed in many ways to protect the rights of the subjects of materials. Issues of this can also be found in Richard Prince’s Instagram artworks.

For my Tumblr share this week I chose to share a comic that discusses plagiarism. In it, the little boy is asking how to cite a source in his paper to an adult who notices that several of the pages of his paper are copied entirely. The adult explains that it is “plagiarism unless you put it in your words,” to which the boy replies, “I did. By coincidence they are exactly the same.” I felt that this comic fits so perfectly into the discussion of whether reproduction of another should be considered not as “plagiarism.” The child’s response to the adult’s concerns feels like the response that many artists would give after being confronted about reproduction in artwork. I think that it points to Bourriaud’s argument that like the boy’s paper, reproduced art forms are no longer “primary” or “original” pieces of art. They are derived and sometimes directly copied from prior work and as such I believe should be cited and give credit to the original creator.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Appropriation and Autonomy

instagram

The two readings for this week were an extension of The Death of the Author. Bourriaud's Postproduction, in particular, reminded me of The Death of the Author in that it cements postproduction techniques as a win for the reader; it allows for art to go "beyond its traditional role as a receptacle of the artist's vision" and generate autonomy, or function to objects of our everyday lives. "Why wouldn't the meaning of a work have as much to do with the use one makes of it as with the artist's intentions for it?" Bourriaud asks.

The second piece, From Here On: Neo Appropriation Strategies in the Contemporary Photography by Joseph Gergel takes a more academic look into appropriation but also warns against manufactured or forced appropriation. Directly questioning the idea of autonomy in postproduction, Gergel adds, "Yet, we must ask whether this digital concept of participation is one of autonomous experience or rather continuously influenced by a variety of media sources." Are we an "active agent" as Bourriaud put it through appropriation, or are we merely copying and reproducing just because everyone is doing so? Edwoudt Boonstra's Anonymous casts a shadow on the sunny outlook on appropriation previously portrayed by Bourriaud and leads us to take a more pessimistic view of it through our modern, digital lense.

This is in a direct conversation with the discussion on filters we had several weeks ago. I believe Sarah showed us the account I tagged above @insta_repeat in her presentation, but these regurgitated filters and repeated aesthetics do rather beg the question 'are we truly more autonomous and free-thinking through appropriating the same old Instagram aesthetics in our posts? Is our contribution a value-add when we passively copy what celebrities and influencers are wearing in their meticulously manufactured sponsored posts? The Death of the Author and the Bourriaud piece celebrated the reader for actively applying their own meanings and interpretations through reproduction and postproduction. I wonder if we indeed possess any meaning or intention in our appropriation anymore.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

For my curated example, I'm choosing to show an etsy page of an artist who recreates famous frames from movies. However, in order to change the value of any particular part of the image, the artist fills the area with the script of the movie itself. I think this whole process evokes some of the important points of postprocessing brought up particularly by the Bourriaud piece.

Much like musical artists of today, the inspiration of future works by others is not only well-known, but expected, and fan reactions to great movies and TV shows spread the word much faster than traditional marketing. With the growth of social media like YouTube and Twitter, and more democratized access to editing tools like Photoshop and Premiere Pro, editing clips of your favorite stuff has never been more appealing.

However, with the work of artists like Mike Matola, we can see how remixes and shuffles are a justifiable art form of their own. Despite an unoriginal image and unoriginal words, Matola's pieces combine them into something truly unique, with its own style and voice. By reducing the image to its basest values and filling that space with something more meaningful, a viewer may have a different reaction to one of Matola's pieces than the original frame, which to me seems to be one of the hallmarks of great art.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Dynamic Aesthetics in Cross-Cultural Dialogue: Interpreting the Formation and Significance of the Chinoiserie Style from the Perspective of Relational Aesthetics

Relational Aesthetics, a significant concept introduced by French curator and art theorist Nicolas Bourriaud in the 1990s, focuses on how art generates meaning through social interactions and the construction of interpersonal relationships, rather than relying solely on the physical artwork itself or the artist’s personal expression. Analyzing the Chinoiserie style from the perspective of Relational Aesthetics allows for a deeper exploration of how this artistic style generates meaning through cultural interaction and the construction of human connections, establishing a new aesthetic relationship between Eastern and Western cultures. This analysis not only emphasizes the material characteristics of Chinoiserie as an art style but also highlights the complex processes of social interaction and cultural exchange behind it.

The Product of Cultural Interaction

Chinoiserie, as a style that blends Eastern and Western elements, perfectly embodies the concept of “art as a social field of interaction” within Relational Aesthetics. This style is not merely a simple imitation of Chinese cultural elements by European artists but gradually took shape through cultural interactions between Europe and China. Through this interaction, Chinoiserie became a cross-cultural aesthetic space, reflecting the European imagination, understanding, and misconceptions of Eastern culture at the time.

In this process, Chinoiserie is not a static artwork but a dynamic result of the continuous interaction between European society and Chinese culture. This style is essentially a product of social relationships, reflecting the social, political, and economic dynamics of Europeans as they encountered, understood, and reinterpreted Chinese culture.

For example, this gold box in the V&A Museum, designed by Michel-Etienne Filassier and made in Paris between 1745–47, features Chinoiserie patterns crafted from shell, mother-of-pearl, and ivory inlays. The design emphasizes the dynamic movement of curves in Chinoiserie, and although the motifs depict Chinese figures, the choice of materials reflects what was popular in the European market at the time. Since the Baroque era, European society has frequently used gilded decorations, not only to highlight the luxurious nature of the objects but also to protect them from physical damage.

The Complexity of Cross-Cultural Relationships

The formation and spread of the Chinoiserie style reflect the complex cross-cultural relationship between Europe and China. From the perspective of Relational Aesthetics, this cross-cultural relationship is not a one-way cultural transplant or simple imitation but a dynamic cultural interaction filled with tension and contradictions. Europe’s imagination and misunderstandings of Chinese culture not only serve as the driving force behind the Chinoiserie style but also form an integral part of its aesthetic significance.

This cultural interaction not only influenced European art styles but also, to some extent, altered Europeans’ perceptions of Eastern culture. Therefore, Chinoiserie is not merely a visual art phenomenon; it also embodies the power dynamics and cultural flows within the relationship between East and West, which lies at the core of what Relational Aesthetics seeks to explore.

ChuCui Palace Dews on the Vines Brooch

Take, for example, the jewelry pioneer of modern Chinoiserie style, ChuCui Palace. Their brooch “Dews on the Vines” combines calla lilies and lilies — two flowers representing the West and East, respectively. The piece cleverly juxtaposes these two flowers to convey the classic East-West blend and cross-cultural characteristics of Chinoiserie. The natural curves derived from Eastern aesthetics are expressed through Western inlay techniques, highlighting the appreciation of Eastern aesthetics, nature, and the free expression of emotions.

In this piece, ChuCui Palace combines traditional Chinese gongbi painting with Western inlay techniques, using varying shades of green and yellow to create the shading effect typical of gongbi art. From the juxtaposition of Eastern and Western floral elements to the harmonious integration of themes and Chinese gongbi painting, alongside the skilled Western inlay techniques blended with Eastern aesthetics, this piece becomes a vivid expression of lyrical and elegant cross-cultural jewelry, enriched by the meticulous detail of traditional Chinese art.

Diverse Audience Participation

From the perspective of Relational Aesthetics, Chinoiserie is not only the creation of artists but also a process in which audiences and consumers participate in cultural construction. In the 18th century, European nobility and the middle class engaged in this cross-cultural exchange by purchasing and displaying Chinoiserie-style artworks. Their choices in home decor and fashion design were, in essence, expressions of recognition and engagement with cross-cultural relationships.

In this interaction, the audience was not a passive receiver but an active participant in the construction of the Chinoiserie style through the consumption and display of these artworks. This participation endowed Chinoiserie with richer social significance, making it an important element in the cultural relationships of European society at the time.

This sculpture group “Touch” at the V&A Museum is part of a series representing the “Five Senses.” These pieces were likely designed to be displayed on wall brackets or mantelpieces and were made by the Derby Porcelain Factory around 1752–55. On closer inspection, one can see that while the figures’ clothing and hats are styled in a Chinese manner, their facial features are distinctly European. This reflects the influence of European perspectives on the final presentation of Chinoiserie artworks and crafts, shaped by the audience’s and consumers’ passive or active “participation.”

The development of the Chinoiserie style in Europe was not merely an artistic phenomenon but also a product of cross-cultural exchange and social interaction. By blending Eastern and Western aesthetic elements, Chinoiserie became a complex medium reflecting Europe’s understanding and misunderstanding of Eastern culture. It embodied the shifting power dynamics of the time and showcased the diverse participation of European audiences in cultural consumption. The uniqueness of this style lies not only in its visual fusion but also in its evolution as a dynamic art form shaped by social relationships. Ultimately, Chinoiserie transcended mere decorative significance, becoming a significant symbol and historical witness of cross-cultural dialogue.

0 notes

Text

26 Noviembre 2023

-Con Berta Durán, mediadora cultural e investigadora en educación artística

1. Investigaciones

R comparte algunos libros para la investigación, que animamos a continuar en el documento colaborativo y la carpeta donde vamos volcando ejemplos también. -Estética relacional, de Nicolás Bourriaud. -El elogio de caminar, de David Le Breton. -The Sbjetcters, de Thomas Hirschhom. -La Acción Directa como una de las Bellas Artes, de La Fiambrera. -Playgrounds. Reinventar la plaza. -Guía política del hogar, como referencia de fanzine. -Los folletos de Espacio Pool. E comenta otras fuentes que aporta también a la investigación: -El arte de no hacer Arte, de Antonio Orihuela. -Alta cultura descafeinada, de Alberto Santamaría. -Y los proyectos de Luis Navarro: Literatura Gris, el archivo situacionista hispano, Industrias Mikuerpo (y blog), el fanzine A Mano.

Por una parte consideramos que debemos tener una base de pensamiento y conocimiento antes de actuar. Por otra pensamos que deberíamos comenzar la acción que nos motiva para no dispersarnos ni desinflar la energía. Se abren 2 áreas de investigación: con lecturas que nutran nuestra cultura y también con experiencias de otros colectivos afines, generando lazos tanto en Málaga como en Andalucía. E habla del colectivo Circadian, que editan el fanzine Dos Pájaros. Y también de Javier Ballester y el Colectivo Infraganti. También está Málaga Paradise y Málaga Ha Vesos. Y FACC, un proyecto de gestión cultural muy interesante en Cádiz. Silvia comenta sobre el espacio culinario Ocoa, que está aquí cerca. Hacen talleres y crean comunidad. Nos preguntamos por el perfil del colectivo que nos alberga en el espacio de reunión y Elena aporta su investigación a partir de la web del correo de Gerald Raunig y la que hay en la puerta del espacio. Progressive Cultural Policies es un colectivo de investigadores. Esta es la web del proyecto que pone en la puerta: https://transversal.at Pero en su correo viene esta, que era anterior: https://eipcp.net Este libro lo ha escrito Gerald Raunig:: https://mitpress.mit.edu/9781584350460/art-and-revolution Y Suburbia acaba de editarle otro: https://www.sub-urbia.es/libro/desamblaje_4672 Este es el Programa de Estudios Radicales que organizan La Casa Azul y Suburbia (el cartel que había en la mesa esta mañana) http://www.per.sub-urbia.es/#apuntate

Este es el congreso que coorganizaron con Suburbia y La Invisible, en el que participan él y Ruth, la mujer que nos abrió la puerta el primer día: https://multiplicity.lainvisible.net/participantes 2. Mediación

E ha invitado a asistir a la reunión a Berta Durán, que conoció en el Congreso Inturjoven. Ella es mediadora cultural con un enfoque participativo y en experiencias colaborativas. Desde lo personal se manifiesta interesada en el tejido asociativo y participativo y en la apertura de la institución cultural a la ciudadanía. Tiene experiencia asamblearia en proyectos como Hortigas. Con afinidad a nuestro proyecto nos comenta el ejemplo de Intramurs en Valencia, o Cabañal Intim. [Ya hemos mencionado en algunas ocasiones el caso del movimiento Salvem Cabanyal. Elena lo refiere en un análisis del artivismo en su conferencia “Fotografía y ciudad”] Berta nos da algunos consejos interesantes para el grupo como aprender a percibir las emociones desde las que trabajamos, dar valor a la experiencia y poder desde la que lo hacemos (cambiar miedos por poderes), medir nuestras energías a la hora de idear proyectos y delegar acciones para no tener que decidir todo entre todas. Hablamos del peligro del arte y la intervención artística como herramienta para instrumentalizar colectivos con la intención de imprimir un discurso, desde una propuesta particular. “Lo poderoso del arte es que existe una propuesta estética”, nos anima a no dejar de lado la estética y lo conceptual. Pero que la propuesta conceptual parta de los intereses de los colectivos. Nos planteamos la duda de si abrir la propuesta a creativos u artistas, artistas profesionales o anónimos. Partiremos de quienes ya conocemos antes de hacer el mapeado. R queda en hablar con Suburbia y E con La Casa Azul, para saber qué colectivos se reúnen allí que estén vinculados con el barrio. 3. Acción

Nos planteamos cómo acceder a la gente. - Carteles, buzoneo. - Búsqueda por las casas. (favorece comunicación tú a tú) - Contacto con colectivos y afines, personas de referencia. - Crear vínculos, relaciones de confianza, escuchar. - Partir de la identidad del territorio. Intereses VS necesidades. - Establecer compromisos a partir de un interés común.

La idea es convocar a una asamblea vecinal en una plaza del barrio. También pensamos en alrededores de Lagunillas, habría que delimitar la zona. Hay que pensar el tipo de comunicación, el diseño más acertado (que no suene ni a flyer publicitario ni a propaganda política). Y seguir con la documentación.

-MAPEO. ACOTAR ZONA. -DISEÑO CARTEL/BUZONEO. (Definir bien la idea, propuesta concreta) -INVESTIGACIÓN TEÓRICA. -INVESTIGACIÓN DE PROYECTOS AFINES. -CREAR UN ARCHIVO (FANZINE). -REUNIÓN DE DIAGNÓSTICO (asamblea vecinal).

Para el mapeo hablamos del material de cartografía crítica de Iconoclasistas. Elena traerá el libro a la próxima reunión, pero está disponible en PDF.

Berta nos aconseja establecer canales claros de escucha. En el momento de reunión con los vecinos, pueden dejar el poder en tus manos, o tú puedes pasarte en la intervención. Eso se va a ver claramente si se genera ese vínculo y se trabaja la relación interpersonal y colectiva. Elena habla de la importancia del manual de asamblearismo publicado por Traficantes, del que hizo un resumen para el Colectivo Fama.

La práctica participativa cuesta, cuesta mantener el vínculo y que la gente se involucre. Hay que observar la tendencia al paternalismo desde la institución así como desde el colectivo. Lo comunitario es lento.

Berta nos habla también de la iniciativa de REACC “Anticonvocatoria”, por si puede interesarnos.

Retomamos la propuesta de registro del proceso que realizó Rocío en su día. Si todas estamos de acuerdo se comenzará a registrar por si luego nos interesa para documentación o difusión (aunque la edición es un trabajo arduo, tenemos que tenerlo en cuenta). También hablamos de fotografía participativa y derivas con los vecinos, integrar la foto que se hagan o el pensamiento en un evento final.

4. Próximas reuniones Las próximas reuniones son 10 de diciembre y 14 de enero. E queda en escribir para confirmar si y cómo continuamos en el espacio y ver la opción de hablar con la directora del Museo Jorge Rando, en Capuchinos. R propone su casa y E también, por si es necesario para alguna reunión intermedia. Dada la densidad de la información, se propone continuar con este tema la semana próxima y dejar para enero la propuesta más personal-creativa. Elena propone preguntar a las compañeras si se encuentran cómodas con ese cambio.

En la reunión de diciembre se abordaría la propuesta 1 realizando el diseño de la acción, el mapeado y el texto de presentación para la gestión con el espacio y la librería. - Diseñaremos el mapeado y acotamos el espacio inicial. - Redactaremos un texto conciso para generar lazos e intereses comunes. - Iniciaremos la búsqueda de espacios y de contactos (contactos sociales y contactos personales) y concretaremos una reunión con la librería. - Haremos un documento para ir incluyendo los contactos. - Haremos un cronograma. En la reunión de enero se abordaría la propuesta 2 haciendo una especie de puzzle-mural poniendo en común nuestro mapa visual para comenzar a trabajar juntas nuestros momentos creativos individuales, para establecer así un punto de partida del trabajo de creación colaborativa y apoyo mutuo en los procesos creativos particulares. E pregunta también por la idoneidad de una reunión con las compañeras del Círculo de Famas. Decidimos que más adelante, cuando tengamos las líneas ya un poco más trabajadas.

5. Personal Es el cumpleaños de E y las compañeras han traído un bizcocho hecho por el padre de C y un librito y una libreta para caminar, observar la naturaleza y escribir.

E agradece emocionada el detalle y comunica que a partir de 2024 va a dejar muchos aspectos de gestión cultural (ya ha comunicado que no continuará en el proyecto del Centro de Fotografía en Málaga tras organizar los Encuentros Málaga Fotográfica) pero que quiere mantener esta actividad con Cronopias porque siente que es importante, en lo intelectual y emocional, y es donde se siente querida.

Y ha comunicado que tiene una situación personal que no le va a permitir estar activa. Es bienvenida siempre a asistir, participar y volver a sentirse activa cuando sea su momento. No sabemos nada de B. De E. K. va a estar trabajando.

C quiere contarnos un proyecto sobre la desvanescencia de lo autóctono en Tolox. Estamos de acuerdo en que lo comente al principio de la próxima reunión.

R propone hacer un correo de Círculo de Cronopias para la comunicación “oficial”. Elena le pide que lo hablemos en la próxima reunión porque hasta ahora está utilizando el correo de Colectivo Fama y tenemos ahí todos los materiales. Habría que pensar también lo que dijimos del Instagram.

0 notes

Text

REFERENCIAS

Pierre Levy. (1999). ¿Qué es la virtualización?. En ¿Qué es lo virtual? (Ed.), 10 (pp. Barcelona). Paidós

Dickinson, E. (2023a). Morí por la belleza (H. d. C. Pujol, Trad.). Literatura random house.

Han B. C. La expulsión de lo distinto : percepción y comunicación en la sociedad actual. (2017). Herder, D.L.

Lispector, C. (2021). El Huevo y la Gallina. Cuentos completos. (pág. 216 - 224). Ediciones Fondo de cultura económica S.A.S. (obra original publicada en 1964)

Lispector, C. (2018). La hora de la estrella. (Poljack, A. Trad.). Ediciones Siruela, S. A. (obra original publicada en 1977)

Lispector, C. (2020). Un soplo de vida. (Vidal, P. Trad.). Ediciones Corregidor. (obra original publicada en 1978)

Schafer, R. M. (2013). El paisaje sonoro y la afinación del mundo. (Cazorla, V. G. Trad.). Prodimag, S. L. (obra original publicada en 1993)

BIBLIOGRAFÍA

Bourriaud, N. (2007). Postproducción. La cultura como escenario: modos en que el arte reprograma el mundo contemporáneo, 13-14.

Han, B. C. (2017). Shanzhai: deconstruction in Chinese (Vol. 8). MIT Press.

Trotereau, J. (2001). El Mundo de las Muñecas. EDITORS, S.A.

Von Kleist, H., & Hoyos, L. E. (2011). Heinrich von Kleist. Sobre el teatro de marionetas y otras prosas cortas. ideas y valores, 60(146), 165-182.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2021, November 17). monstera. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/plant/Monstera

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2022, January 23). Pan Gu. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Pan-Gu

PELÍCULAS

Almodóvar, P. (Director). (1991). Tacones lejanos [Mubi]. el deseo.

Kaufman, C. (Director). (2008). Synecdoche, New York [Mubi]. Sony Pictures.

VIDEOS

Letras del Valle. (2016, 7 de marzo). Mi Hermano y Yo - Los Hermanos Zuleta (Letra) [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X9H4ul5cstg

IMÁGENES

Cruz, V. (2023). ¿Acaso alguien puede pensar en los niños? [Collage]. Collage digital con imágenes de stock.

(Ilustración DE CAÍN Y ABEL encontrada en Google). Autor(es)desconocidos.

Fragmento del primer escrito de trabajo de grado sobre un cuaderno, mencionado en el párrafo 1 de la página 1. (Fotografía)

Cruz, V. (2024). Aterrizaje de las uvas [Collage]. Pintura/collage digital.

Cruz, V (2024). La dormición del bebito [Collage]. Collage digital con imágenes de stock.

Cruz, V. (2024). Lotería nuestra [Collage]. Collage digital con imágenes de stock.

Cruz, V. (2024). Bodegón [Collage]. Collage digital con imágenes de stock.

Cruz, V. (2024). Cuarto PT2 [Collage]. Collage digital con imágenes de stock.

Cruz, V. (2024). Castillo y tornado en dirección a tus pies [Collage]. Pintura/collage digital con imágenes de stock.

Cruz, V. (2024). Bogotá D1, de todos [Collage]. Pintura/collage digital con imágenes de stock.

Cruz, V. (2024). La sonrisa es la ventana de [Collage]. Pintura/collage digital con imágenes de stock.

Cruz, V. (2024). Falseamiento y venta de los secretos [Collage]. Collage digital con imágenes de stock.

Trotereau J. (2001) Una pintura de cinco muñecas matrioshkas tradicionales pertenecientes a un mismo juego. [Pintura] Acuarelas.

Cruz, V. (2024). Jugador acicalándose a través de su muñeca [Collage]. Pintura/collage digital con imágenes de stock.

Cruz, V. (2024). La sonrisa con ventana de [Collage]. Collage digital con imágenes de stock.

Cruz, V. (2024). Hoyo cantador [Collage]. Collage digital con imágenes de stock.

Cruz, V. (2024). Jardín grieta[Collage]. Collage digital con imágenes de stock.

Cruz, V. (2024). Batirburrillo frutal [Collage]. Collage digital con imágenes de stock.

CARITASUCIA x HELADINAA

0 notes

Text

In Bourriaud’s “Postproduction,” he gives an overview of post production techniques and how they redefine already produced forms, which adds an almost philosophical spin on how we produce meaning, ownership, and the limits of art. In Gergel’s “From Here On,” he describes how the internet has altered our visual landscape, and how image appropriation interacts with the idea of post production to generate new forms of art that transform existing photographs. Both authors bring up questions on what defines art and reference the Dadaist movement, drawing parallels with pieces such as Duchamp’s readymades.

I found it interesting how the distinction between art and non-art can separate pieces from being appreciable and even ethical. For example, as mentioned in the Gergel piece, Pavel Maria Smejkal appropriates photojournalistic images and erases the subject, perhaps as a commentary on the erasure of history. Here, the emptiness is stark, evident, and creates an almost self-aware indication of post production, and the fundamental nature of the piece serves to generate some sort of artistic meaning and commentary. This contrasts the 1982 National Geographic cover photo scandal, where it wasn’t evident that the edited cover photo was serving as a mere graphic instead of a photo journalistic documentation. The misalignment in perception between the “artist” and audience generated kickback and trust/ethics concerns. Furthermore, the inclusion of the edited image within the main magazine section, which was clearly understood to be photo journalistic in nature, made the editing seem even more unethical, as mirrored in the response at the time and the comment section. This contrast between the two instances of editing point to the importance of understanding intention – even if a work may not seem like art, the understanding that it is can be critical to its reception (and how ethical it is), as in the case with readymades – and the emphasis we place on making a distinction between photography as a technology to document and photography as a medium for expression and artistic appropriation.

0 notes

Text

I choose to include some examples of handmade photomontages by Bhoomica Patel, an artist who uses her Wordpress to share her work. This piece is intended to showcase the disparity in India - both economic and otherwise. It shows the Taj Mahal and the Golden Temple behind images of the polluted river Ganga, abandoned children who are begging for food, and a woman walking with pails of water in search of clean water.

After reading the Bourriaud and Gergel pieces, I was drawn to an idea that both pieces talked about, which was the manner in which digital photography has changed our concept of “taking art” from someone and the difference between using someone’s art and making it one’s own and simply “copying”. I found these works because I was curious to learn about if this concept of photomontages and reusing artworks was popular amongst artists outside the western world.

0 notes