#Bohemia regent

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Bohemia Regent / Marks & Spencer Czech Pilsner Lager (Picked up at a M&S Food in London). A 2 of 4. This is a beer -- it is a bit sweeter and more forward with the caramel malt than I was expecting. It delivers a reasonably nice balance and clean finish, and the slight malt complexity is a nice surprise.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

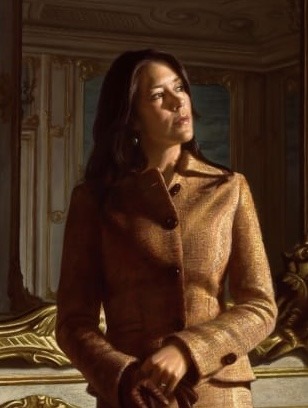

9 Royal Mary’s of history - Reigning and Consorting: -> 1. Mary of Burgundy: Consort of Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor (1457–1482). -> 2. Mary of Hungary (Mary of Habsburg): Queen consort of Louis II of Hungary and Bohemia (1505–1558). -> 3. Mary I of England: Reigned 1553–1558 (1516–1558). -> 4. Mary of Guise: Queen consort of James V of Scotland, regent for Mary, Queen of Scots (1515–1560). -> 5. Mary, Queen of Scots: Reigned 1542–1567 (1542–1587). -> 6. Mary II of England: Reigned 1689–1694 (1662–1694). -> 7. Mary of Modena: Queen consort of James II of England, regent for James Francis Edward Stuart (1658–1718). -> 8. Mary of Teck (Queen Mary): Consort of George V of UK, reigned 1910–1936 (1867–1953). -> 9. Mary Elizabeth Donaldson (Queen Mary): current Queen consort of Frederick X of Denmark since 14th January 2024 (1972-).

#ktd#Royal history#european history#Mary I#mary ii#mary queen of scots#queen mary#Mary of teck#Mary of Modena#Mary of guise#Mary of burgundy#Mary of Hungary#European royalty#royal#royalty#brf#british royal family#british royalty#british royal fandom#Art#art history#Denmark

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who ordered the death of king Wenceslaus III?

It's early afternoon of August 4th 1306 in beautiful Olomouc, Margraviate of Moravia. The young Bohemian king Wenceslaus III is a guest of the bishop, who offered him his hospitality on king's campaign to Poland. Václav had recently resigned his position as the king of Hungary, but now he's determined to defend his hereditary claim to the Polish crown.

Wenceslaus had just finnished lunch and decided to rest in private chambers. Suddenly there's a scream and the guards catch Konrad of Mulhov (1), a German knight, with a bloodied blade just outside of king's chambers. The king lies inside, stabbed to death. His death means the end of the Přemyslids, who had ruled Bohemia for over 400 years.

Konrad is killed immediately. We have the name of the killer (unless of course he was being framed), but even 700 years later we don't know who paid for king Wenceslaus' death. Even sources of that time can't agree on the culprit.

Elizabeth of Töss - a Hungarian princess, the last member of the House of Árpád. She was betrothed to Wenceslaus once. A king of Hungary and heir to the Bohemian throne is quite the catch. But once Wenceslaus gave up the Hungarian crown, the engagement was terminated. After this Elizabeth never got married and spent the rest of her life in a closter. The loss of an advantageous marriage and feelings of being betrayed seem like enough of a motive. But did Elizabeth have good enough connections to get a murderer right into king's chambers?

Charles Robert of Anjou- Wenceslaus took the Hungarian crown (thanks to his fathers political machinations) under quite tumultuous circumstances. After the previous king of Hungary got murdered, Charles Robert of Anjou was Wenceslaus' main opponent in pursuit of the crown and Wenceslaus' success only fanned the flames of opposition. It would make sense for Charles to get rid of his greatest rival. However when Wenceslaus gave up the Hungarian crown, he did so in favor of Otto of Bavaria. Would Charles ignore this new threat and arrange the death of his former rival?

Albert I of Germany - the king of Holy Roman Empire. Not too long ago he waged war Wenceslaus' father to slow down his rise in power. And even though he and Wenceslaus had made peace, the king of Bohemia still has a lot of power in the Empire. Plus since Wenceslaus has no legitimate children, if he dies, Bohemia will fall right into Albert's lap. After all, a few months after Wneceslaus' death Albert attacked the Bohemian kingdom to claim it for his son Rudolph. But had he been the culprit, would he wait that long?

Władysław I Łokietek - he's not happy with the Přemyslids ruling over Poland and would in fact like to claim the Polish crown for himself. He'd been campaigning against them for the past two years and now that Wenceslaus is coming to Poland with an army, it might be time to strike. But could he get a murderer to Wenceslaus' court?

Henry of Carinthia - while Wenceslaus is leading his army to Poland, Henry is his regent back in Prague. Maybe he would like the royal power for himself? His marriage with Anne, the eldest of Wenceslaus' sisters would only help with that. We know the Bohemian nobility elected him king after Wenceslaus' death, so did he decide to speed up the process?

The Bohemian nobility - over the past century they'd gained quite a lot of power and amassed several reasons to be mad at the king. It could be revenge for the execution of Zavis of Falkenstein, one of their own (2). It could be a solution to proprietary disputes. It could be an attempt to help one of Wenceslaus' opponents. But if such conspiracy had happened, wouldn't we have found out by now?

(1) Some sources name him as Konrad of Botenstein, but for the purposes of this poll it doesn't really matter.

(2) To me this doesn't feel like a valid reason since it was Wenceslaus' father who ordered to execute Zavis, but it is what some sources claim.

#čumblr#polls#history#czech history#i don't even care if anyone votes the idea would haunt me until i made it#and yes i should be studying instead of this

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 8: Anne of Bohemia and Hungary

Anne of Bohemia and Hungary (also known as Anna Jagellonica)

Born: 23 July 1503 Died: 27 January 1547

Parents: Vladislaus II of Hungary and Anne of Foix-Candale Archduchess Consort of Austria, Queen Consort of Hungary, Bohemia and Croatia Children: Elizabeth, Queen of Poland Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor Anna, Duchess of Bavaria Ferdinand II, Archduke of Austria Maria, Duchess of Jülich-Cleves-Berg Archduchess Magdalena Catherine, Queen of Poland Eleanor, Duchess of Mantua Archduchess Margaret Barbara, Duchess of Ferrara Charles II, Archduke of Austria Archduchess Helena Joanna, Grand Duchess of Tuscany

Anna of Bohemia and Hungary was the oldest child and only daughter of Vladislaus II of Hungary and his third wife Anne of Foix-Candale. Her younger brother was the King of Hungary, Croatia and Bohemia. On her father’s side, her grandparents were Casimir IV of Poland and Elisabeth of Austria. On her mother’s side her grandparents were Gaston de Foix, Count of Candale, and Catherine de Foix.

She was born in Buda (actualmente Budapest) Her mother died shortly after her brother’s birth. Their father died on 13 March 1516 and the two siblings were left in the care of the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I. Maximilian arranged for Anne to marry his grandson, Archduke Ferdinand of Austria.

Anne received a humanist education focused on problem-solving skills. There was also an emphasis on self-defense with weapons and other physical skills and hunting. She was instructed in music and dance and came into contact with many humanists visiting the imperial library.

On 26 May 1521 in Linz, Austria, Anne and Ferdinand were married. Ferdinand governed Habsburg hereditary lands on behalf of his older brother Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. It was stipulated that if Anne’s brother died without heirs, Ferdinand would succeed him.

On 29 August 1526, Louis was thrown off his horse at the Battle of Mohács against Suleiman the Magnificent. As he had no legitimate heir the thrones of Hungary and Bohemia were left vacant. Ferdinand quickly claimed them. He was elected king with Anne as his queen on 24 October 1526.

Hungary, on the other hand, was a different matter. Ferdinand was proclaimed king by a small group of nobles, but another group did not want a foreign ruler so they elected John Zápolya as an alternative king. The conflict that resulted lasted until 1570 when the Treaty of Speyer was signed in favor of Anne’s son Maximilian.

In 1531, Ferdinand’s brother Charles V elected him as his successor and was to be proclaimed King of the Romans after his death.

Anne was trusted by her husband, serving as regent in his absence and presiding over matters of great importance. She became renowned for her charity and wisdom.

All 15 of their children were born in Bohemia or Austria.

She died on 27 January 1547, aged 43, in Prague, after the birth of her last daughter.

#1500s#16th century#house of habsburg#women history#history#women in history#reinessance#hungary#austrian history

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Red-Headed League

This is the second published short story, after "A Scandal in Bohemia"

A massive slam on tradesmen from out of nowhere!

Arthur Conan Doyle was himself an on-and-off Freemason, but only got as far as the third degree. Being involved in the movement seems to have been common in middle and high society, with no less than the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) as Grand Master at the time of publication. The current Grand Master is Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, first cousin once removed to the King and 40th in line to the throne.

Fleet Street is a London street that was - and still is - synonymous with the newspaper industry, although they have all gone from the area now. It's also associated with Sweeney Todd.

With around 4.2 million people living within the then-boundaries of London at the time, there would have been quite a few redheaded men.

Snuff is snorting tobacco. It was used in the House of Commons as smoking has been banned in there since 1693 (the place was dimly lit enough until the TV cameras went in without cigarette smoke making it worse!) and the boxes for it remain, but it is little used now. However, you can still buy it without paying tobacco taxes.

A gold sovereign was a gold coin with a nominal value of £1; today, partly because the gold content, it is worth far more than that. The Royal Mint still make them and are now selling Charles III ones. It was common for gentlemen to have one on a watch-chain; Jabez Wilson has a Chinese equivalent instead.

The Encyclopedia Brittanica at this point was 25 volumes long.

Aldersgate Underground station is now called Barbican and is on the Hammersmith & City, Circle and Metropolitan Lines, also being an "open-air" station. It contains some disused tracks that were used by Thameslink services until 2009, when the branch line from Farringdon to Moorgate was shut due to platform extensions at the former severing the line.

A good part of the Aldersgate area was destroyed in the Second World War, resulting in the construction of the Barbican Estate and associated arts centre. The brutalist construction of both has resulted in it becoming a popular location for filmmakers; it has recently played Coruscant in Andor.

St. James's Hall was a concert hall in Regent Street; it was the principal venue for concerts in the city at the time until the 1900s, when it was supplanted by Queen's Hall, closed, and demolished.

Royal Dukes trump regular Dukes; the titles are given to members of the royal family, generally either when they turn 21 or when they marry. The title enables the hold to call themselves a Prince if not already one. Historically they were hereditary but ceased being royal once passing beyond the grandsons of a monarch, so the Duke of Kent's son, George Windsor, will not be a prince once he inherits the dukedom. The recent fourth creation of Duke of Edinburgh for the other Prince Edward is lifetime only though.

Napoleons were French gold coins with a nominal value of 20 francs. While the nickname comes from Bonaparte, they were minted under successor governments (the Third Republic by this time) until 1914 and remain collector's items.

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Denis Wirth-Miller (1915-2010), born Wurtmüller in Folkestone to a Bavarian father and English mother.

Denis Wirth-Miller: Bohemian artist who enjoyed a close association with Francis Bacon.Denis Wirth-Miller was one of a group of artists who for many years injected the spirit of bohemia into the life of Wivenhoe, a small shipbuilding and repairing town on the Essex coast. The jollifications of Wirth-Miller, his partner, the James Bond illustrator Richard "Dickie" Chopping, and the painter Francis Bacon remain the stuff of local legend.

Such stories, true or untrue – among the latter is one that after Bacon's death his former Wivenhoe house was kept as a shrine by Denis and Dickie – have tended to overshadow Wirth-Miller's achievements as a painter. One recognition of this will be a forthcoming small retrospective at the Minories Art Gallery, Colchester.

Also undermining Wirth-Miller's reputation was the fact that from the early 1970s sight problems hindered him and that latterly he suffered from dementia. All this must have been hard for a man who had shown in London's leading galleries and had work in the collections of the Queen, the Arts Council and Contemporary Art Society.

Wirth-Miller was born in Folkestone, Kent, in 1915, where his Bavarian father Johann Wirthmiller (Denis later Anglicised his name) ran a busy hotel. Wirth-Miller's mother moved him to Bamburgh in her home county of Northumberland, where he was raised by his grandmother.After school, he joined Tootal Broadhurst Lee, the textile manufacturers in Manchester, where innate talent prompted his appointment as a designer. After arriving in London early in 1937 he met Dickie Chopping, who moved into one of the painter Walter Sickert's former studios in north London, where Denis was living. Thus began a lifelong relationship; in December 2005 they became the first in Colchester to make a civil partnership.

It was not without disagreements, even how about they first met – according to Chopping at a Regent's Park charity garden party, according to Wirth-Miller at the Café Royal, a celebrated meeting point for gay men. A friend was concerned about the vulnerability of the Sickert flat to bomb damage and advised them to leave London, lending them the dilapidated Felix Hall in Kelvedon, Essex. There, they scraped a living gardening and other jobs.Then, importantly, they met the painters Cedric Morris and Arthur Lett-Haines, who had established the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing, first at Dedham and, when that was destroyed by fire, at Benton End. The artist Mollie Russell-Smith recalled how, as a student lacking an easel, with trepidation she knocked on the door at Benton End and it was "flung open by three young men" – Chopping, Wirth-Miller and Lucian Freud.

"They bundled me in, assuming that I had come to be a student, and Dickie showed me all over the house with great enthusiasm and charm. I was enchanted."

https://www.independent.co.uk/.../denis-wirthmiller...

https://www.apollo-magazine.com/denis-wirth-miller-bacon.../

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

do you have suggestions for names for future queens that arent magarete?

It's difficult, you know, because the case for Margrethe is just very strong given her predecessors. It's actually one of Danish history's most curious coincidences that QMII became QMII. She was named for her late British grandmother and presumably, at the time of her birth, Frederik and Ingrid were hopeful they'd get themselves a little Christian sooner or later. But she so happens to end up becoming Queen of Denmark and she so happens to share name with the closest we've come to having a female monarch of Denmark. That is pretty amazing, if you ask me.

And ON TOP of I and II, we have Margrethe Sambiria – consort to Christoffer I and first female regent of Denmark – also known as "Margrethe Sprænghest" (or Margrethe Burst-horse!!1!) as she was known to ride horses to their death, leading her army across the country. It's just... difficult to argue against continuing the tradition QMII started since we've just had a myriad of badass Margrethes 😅

BUT, some suggestions:

Thyra – We actually don't know a whole lot about Thyra Danebod yet she's a legend. Mother of the Kingdom of Denmark, what's not to like? (Well, that would be its English pronunciation but hey-ho. Lest we forget that Norway's Ingrid Alexandra would've been Tyra Eufemia had Haakon and Mette-Marit felt bold enough 😂)

Dagmar – You'd think I was naming daughters of Christian IX but I'd give this particular one to Dagmar of Bohemia (actual name Markéta, or in Danish – you guessed it – Margrethe). Again, a legendary Queen and she who gave the Dagmar Cross its name. Doesn't hurt that "we" had a Russian Empress named Dagmar either.

Ingrid – You knew she'd be coming and she doesn't need an explanation. Queen Ingrid was instrumental to the DRF. While it may not be used for a potential firstborn daughter in the forthcoming generation (due to aforementioned Norwegian Ingrid), I can easily see her used in the future.

Louise – It has a dated feel, I understand but hear me out: Technically speaking, the reason the Glücksburgs are on the Danish throne today is because of Louise of Hesse-Kassel 🤷♀️ We've also had no less than 4 Queen consorts named Louise.

Emma – Bit of an outsider, Emma of Normandy does not get the respect nor the attention she deserves. And it's a timeless name!

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Partial List of Royal Saints

Saint Abgar (died c. AD 50) - King of Edessa, first known Christian monarch

Saint Adelaide of Italy (931 - 999) - Holy Roman Empress as wife of Otto the Great

Saint Ælfgifu of Shaftesbury (died 944) - Queen of the English as wife of King Edmund I

Saint Æthelberht of Kent (c. 550 - 616) - King of Kent

Saint Æthelberht of East Anglia (died 794) - King of East Anglia

Saint Agnes of Bohemia (1211 - 1282) - Bohemian Princess, descendant of Saint Ludmila and Saint Wenceslaus, first cousin of Saint Elizabeth of Hungary

Saint Bertha of Kent (c. 565 - c. 601) - Frankish Princess and Queen of Kent as wife of Saint Æthelberht

Saint Canute (c. 1042 - 1086) - King of Denmark

Saint Canute Lavard (1096 - 1131) - Danish Prince

Saint Casimir Jagiellon (1458 - 1484) - Polish Prince

Saint Cormac (died 908) - King of Munster

Saint Clotilde (c. 474 - 545) - Queen of the Franks as wife of Clovis I

Saint Cunigunde of Luxembourg (c. 975 - 1033) - Holy Roman Empress as wife of Saint Henry II

Saint Edmund the Martyr (died 869) - King of East Anglia

Saint Edward the Confessor (c. 1003 - 1066) - King of England

Saint Edward the Martyr (c. 962 - 978) - King of the English

Saint Elesbaan (Kaleb of Axum) (6th century) - King of Axum

Saint Elizabeth of Hungary (1207 - 1231) - Princess of Hungary and Landgravine of Thuringia

Saint Elizabeth of Portugal (1271 - 1336) - Princess of Aragon and Queen Consort of Portugal

Saint Emeric (c. 1007 - 1031) - Prince of Hungary and son of Saint Stephen of Hungary

Saint Eric IX (died 1160) - King of Sweden

Saint Ferdinand (c. 1199 - 1252) - King of Castile and Toledo

Blessed Gisela of Hungary (c. 985 - 1065) - Queen Consort of Hungary as wife of Saint Stephen of Hungary

Saint Helena (c. 246 - c. 330) - Roman Empress and mother of Constantine the Great

Saint Henry II (973 - 1024) - Holy Roman Emperor

Saint Isabelle of France (1224 - 1270) - Princess of France and younger sister of Saint Louis IX

Saint Jadwiga (Hedwig) (c. 1373 - 1399) - Queen of Poland

Saint Joan of Valois (1464 - 1505) - French Princess and briefly Queen Consort as wife of Louis XII

Blessed Joanna of Portugal (1452 - 1490) - Portuguese princess who served as temporary regent for her father King Alfonso V

Blessed Karl of Austria (1887 - 1922) - Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, King of Croatia, and King of Bohemia

Saint Kinga of Poland (1224 - 1292) - Hungarian Princess, wife of Bolesław V of Poland and niece of Saint Elizabeth of Hungary

Saint Ladislaus (c. 1040 - 1095) - King of Hungary and King of Croatia

Saint Louis IX (1214 - 1270) - King of France

Saint Ludmila (c. 860 - 921) - Czech Princess and grandmother of Saint Wenceslaus, Duke of Bohemia

Blessed Mafalda of Portugal (c. 1195 - 1256) - Portuguese Princess and Queen Consort of Castile, sister of Blessed Theresa of Portugal

Saint Margaret of Hungary (1242 - 1270) - Hungarian Princess, younger sister of Saint Kinga of Poland and niece of Saint Elizabeth of Hungary

Saint Margaret of Scotland (c. 1045 - 1093) - English Princess and Queen Consort of Scotland

Blessed Maria Cristina of Savoy (1812 - 1836) - Sardinian Princess and Queen Consort of the Two Sicilies

Saint Matilda of Ringelheim (c. 892 - 968) - Saxon noblewoman and Queen of East Francia as wife of Henry I

Saint Olaf (c. 995 - 1030) - King of Norway

Saint Olga of Kiev (c. 900 - 969) - Grand Princess of Kiev and regent for her son Sviatoslav I, grandmother of Saint Vladimir the Great

Saint Oswald (c. 604 - 642) - King of Northumbria

Saint Radegund (c. 520 - 587) - Thuringian Princess and Frankish Queen

Saint Sigismund of Burgundy (died 524) - King of the Burgundians

Saint Stephen of Hungary (c. 975 - 1038) - King of Hungary

Blessed Theresa of Portugal (1176 - 1250) - Portuguese Princess and Queen of León as wife of King Alfonso IX, sister of Blessed Mafalda

Saint Vladimir the Great (c. 958 - 1015) - Grand Prince of Kiev and grandson of Saint Olga of Kiev

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

As I'm currently indexing this blog or, rather, meta-tagging posts in my new version of it on the Blogger website (I will post proper link as soon as it's finished), I decided to compile a list of all the women who feature (or receive a mention however fleetingly) within it. I have tried to trawl the blog ''with a fine toothcomb'', but I'm bound to have missed a few names - oh well! Here is the list as complete as I can muster. The women appear in (broadly) alphabetical order by first name. *** NB it is still a work in progress ***

VOCALISTS & MUSICIANS

Alice Waterhouse (flute) * Amy Winehouse * Angel Olsen * Annie June Callaghan * Ari Up & The Slits * Be Good Tanyas, The * Billie Holiday * Bjork * Black Belles, The * Cait O’ Riordan (Pogues) * Calista Williams (Bluebird) * Cindy Wilson & Kate Pierson (The B52s) * Cistem Failure * Clementine Douglas * Cosey Fanni Tutti * DakhaBrakha (well, 3/4 of them!) * Debbie Harry * Edith Piaf * Elizabeth Morris (Allo Darlin') * Holly Golightly * HoneyLuv * Katy-Jane Garside * Kelis * Kim Deal (Pixies & Breeders) * Maxine Peake * Maxine Venton & Mimi O'Malley (Captain Hotknives) * Meg White * Melanie Safka * Nico * Nina Simone * Patti Rothberg * Penny Ford (Snap!) * PJ Harvey * Rhoda Dakar (Special AKA) * Seamonsters, The * Siouxsie Sioux * Suzanne Vega * Tray Tronic * Trish Keenan (Broadcast)

VISUAL ARTS

Annegret Soltau * Anne Ophelia Dowden * Artemisia Gentileschi * Barbara Regina Dietzsch * Beverly Joubert * Camille Claudel * Clara Peeters * Dale DeArmond * Doreen Fletcher * Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale * Élisabeth Sonrel * Elisabetta Siriani * Elizabeth Mary Watt * Ella Hawkins * Evelyn De Morgan * Frida Kahlo * Gertrude Abercrombie * Helen Martins * Kate Gough * Laura Knight (Dame) * Leonora Carrington * Lily Delissa Joseph * Liza Ferneyhough * Magdolna Ban * Mandy Payne* Mary Delany * Miina Akkijrkka * Ndidi Ekubia * Pamela Colman-Smith * Paula Rego * Rachel Gale * 'Romany Soup' * Sarah Vivien * Shirley Baker * Siirkka-Liisa Konttinen * Sofonisba Anguissola * Sonia Delaunay * Tish Murtha * Vali Myers * Vanessa Bell

COMEDY, DANCE & DRAMA

Alicia Eyo & Carol Morley ('Stalin My Neighbour') * Claire Foy * Daisy May Cooper * Gabrielle Creevy & Jo Hartley ('In My Skin') * Isadora Duncan * Jessica Williams ('Love Life') * Lesley Sharp, Michelle Holmes & Siobhan Finneran ('Rita, Sue & Bob Too') * Michaela Coel ('I May Destroy You') * Morgana Robinson * Samantha Morton * Yasmin Paige (Jordana Bevan in ‘Submarine)

WRITERS, JOURNALISTS, SCHOLARS & POETS

Agatha Christie (MBE) * Andrea Dunbar * Anaïs Nin * Angela Thirkell * Anna Funder * Anna Wickham * Edith Holden * Elizabeth O'Neill * Enid Blyton * Harriet Beecher Stowe * Helen Castor (Dr.) * Hilary Mantel * Janina Ramirez (Dr.) * Jeannette Kupfermann * Jenny March (Dr.) * Jenny Wormald (Dr.) * Lia Leendertz * Mary Oliver * Orna Guralnik (Dr.) * Rachel Beer * Susie Boniface * Virginia Woolf

HISTORICAL FIGURES

Anne, Queen of Great Britain * Anne Boleyn, Queen of England * Anne of Cleves, Queen of England * Boudicca, Queen of the Iceni * Cartimandua, Queen of the Brigantes * Catherine de’ Medici, Queen Consort/Regent of France * Catherine Parr, Queen of England * Catherine of Aragon, Queen of England * Catherine of Valois, Queen of England * Christine de Pizan * Cixi, Empress of China (aka Empress Tz'u-hsi ) * Eleanora of Austria, Queen of France * Eleanor of Aquitaine, Queen of France; Queen of England; Duchess of Aquitaine * Eleanor of Castile * Eleanor Talbot ("The Secret Queen") * Elizabeth I Queen of England * Elizabeth Woodville, Queen Consort of England * Elizabeth of York, Queen Consort of England * Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia * Hatshepsut, Pharaoh of Egypt *Hildegard of Bingen * Isabeau of Bavaria, Queen of France * Isabella I, Queen of Castile * Isabella of Aragon, Princess of Asturias * Isabella of Portugal, Empress Consort of Holy Roman Empire and Queen Consort of Spain, Germany & Italy * Isabella of France, Queen of England * Jacquetta of Luxemburg * Jane Grey (Lady), Queen of England for Nine Days * Jane Seymour, Queen of England * Juana (aka Joanna), Queen of Castile * Katherine Howard, Queen of England * Louise of Savoy, Regent of France * Margaret of Anjou, Queen Consort of England * Margaret of Austria [check which one] * Margaret Beaufort, Lady * Marie Antoinette, Queen of France * Mary I, Queen of England * Mary II, Queen of England, Scotland & Ireland * Mary, Queen of Scots * Mary of Austria [check which one] * Mary of Burgundy, Duchess * Matilda, Holy Roman Empress * Melisende, Queen of Jerusalem * Sophia of Hanover, Electress * Tatya Betul, Empress of Ethiopia * Theodora, Empress of Byzantium * Victoria, Queen of England & Empress of India

SAINTS & BIBLICAL/CHRISTIAN REFERENCES

Anna (wife of Tobit) * Apollonia (Saint) * Barbara (Saint) * Catherine of Alexandria (Saint) * Ecclesia * Eve (the first woman) * Felicitas of Rome (Saint) * Genevieve (Saint) * Godeberta * Jael * Jezebel * Judith * Lucy (Saint) * Margaret of Scotland (Saint) * Mary Magdalene * Rahab * Rose of Lima (Saint) * Synagoga * The Queen of Sheba * Thérèse of Lisieux (Saint) * Virgin Mary, The* "Whore of Babylon", The * Ursula (Saint)

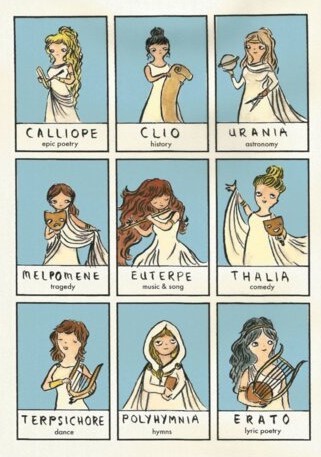

MYTHOLOGICAL

Anat * Asherah * Astarte * Atalanta * Aurora * Baba Yaga * Circe * Chhinnamasta * Clio/Kleio * Demeter (Rmn: Ceres) * Dido, Queen of Carthage * Durga * Elaine of Astolat * Europa * Eurydice * Hathor * Hesperides * Io * Isolde/Iseult * Isis * Juno (Gk: Hera) * Kali * Kriemhild/Gudrun * Kudshu * Lakshmi * Persephone (Rmn: Proserpine) * Radha * Sabine Women, The * Sati * Sedna * Sirens, The (half-female, half-bird) * Three Graces, The * Valkyries, The * Venus (Aphrodite)

WIVES, MUSES, CONSORTS & SIGNIFICANT OTHERS

Anastasia Romanovna (wife of Ivan the Terrible) * Anne Hyde (1st wife of James, Duke of York; she did not live long enough to see him become James II) * Anne Lovell (wife of Sir Francis Lovell) * Anne of Denmark (wife of James VI of Scotland/James I of England & Ireland) * Bella Chagall (wife of Marc Chagall) * Catherine of Braganza (wife of Charles II) * Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (Queen of England as wife of George III) * Clementine Churchill (wife of Winston Churchill) * Diane de Poitiers (royal mistress to the French king, Henry II) * Emma Hamilton, Lady (mistress of Lord Horatio Nelson) * Evelyn Pyke-Nott (wife of John Byam Shaw) * Françoise Gilot (partner of Pablo Picasso) * Frances Grey, Duchess of Suffolk (mother of Lady Jane Grey) * Henrietta-Maria (wife of Charles I) * Lady Martha Temple (wife of Sir William Temple) * MacDonald sisters, The (Alice, Georgiana, Agnes and Louisa) * Marguerite of Navarre/Angoulême (sister of French king, Francis I) * Mary of Modena (2nd wife of James VI and I, King of Scotland, England, and Ireland) * Mary Shelley (mentioned as wife of Percy Bysshe Shelley, though a renowned author in her own right) * Mary Soames (daughter of Winston Churchill & wife of Christopher Soames) * Mary Stuart (daughter of Charles I and mother of the future William III) * Mary Watts (wife of George Frederic Watts, and designer and artist in her own right) * Olga Khokhlova (1st wife of Pablo Picasso) * Portia (wife of Brutus) *

2OTH CENTURY & MODERN DAY

Christabel Pankhurst * Emily Wilding Davison * Emmeline Pankhurst * 'Gulabi Gang' * Hannah Hauxwell * Helen Keller * Hilary Clinton * Liz Truss * Margaret Campbell, Duchess of Argyll * Mata Hari * Melina Mercouri * Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe * Rahima Mahmut * Sylvia Pankhurst *

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Drahomíra of Stodor (c. 877 or 890 – died after 934 or 936) was Duchess consort of Bohemia from 915 to 921, wife of the Přemyslid duke Vratislaus I. She also acted as regent of the Duchy of Bohemia from 921 to 924 during the minority of her son Wenceslaus. She is chiefly known for the murder of her mother-in-law Ludmila of Bohemia by hired assassins.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Events 7.11 (before 1920)

472 – After being besieged in Rome by his own generals, Western Roman Emperor Anthemius is captured in St. Peter's Basilica and put to death. 813 – Byzantine emperor Michael I, under threat by conspiracies, abdicates in favor of his general Leo the Armenian, and becomes a monk (under the name Athanasius). 911 – Signing of the Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte between Charles the Simple and Rollo of Normandy. 1174 – Baldwin IV, 13, becomes King of Jerusalem, with Raymond III, Count of Tripoli as regent and William of Tyre as chancellor. 1302 – Battle of the Golden Spurs (Guldensporenslag in Dutch): A coalition around the Flemish cities defeats the king of France's royal army. 1346 – Charles IV, Count of Luxembourg and King of Bohemia, is elected King of the Romans. 1405 – Ming admiral Zheng He sets sail to explore the world for the first time. 1410 – Ottoman Interregnum: Süleyman Çelebi defeats his brother Musa Çelebi outside the Ottoman capital, Edirne. 1476 – Giuliano della Rovere is appointed bishop of Coutances. 1576 – While exploring the North Atlantic Ocean in an attempt to find the Northwest Passage, Martin Frobisher sights Greenland, mistaking it for the hypothesized (but non-existent) island of "Frisland". 1616 – Samuel de Champlain returns to Quebec. 1735 – Mathematical calculations suggest that it is on this day that dwarf planet Pluto moved inside the orbit of Neptune for the last time before 1979. 1789 – Jacques Necker is dismissed as France's Finance Minister sparking the Storming of the Bastille. 1796 – The United States takes possession of Detroit from Great Britain under terms of the Jay Treaty. 1798 – The United States Marine Corps is re-established; they had been disbanded after the American Revolutionary War. 1801 – French astronomer Jean-Louis Pons makes his first comet discovery. In the next 27 years he discovers another 36 comets, more than any other person in history. 1804 – A duel occurs in which the Vice President of the United States Aaron Burr mortally wounds former Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton. 1833 – Noongar Australian aboriginal warrior Yagan, wanted for the murder of white colonists in Western Australia, is killed. 1836 – The Fly-fisher's Entomology is published by Alfred Ronalds. The book transformed the sport and went to many editions. 1848 – Waterloo railway station in London opens. 1864 – American Civil War: Battle of Fort Stevens; Confederate forces attempt to invade Washington, D.C. 1882 – The British Mediterranean Fleet begins the Bombardment of Alexandria in Egypt as part of the Anglo-Egyptian War. 1889 – Tijuana, Mexico, is founded. 1893 – The first cultured pearl is obtained by Kōkichi Mikimoto. 1893 – A revolution led by the liberal general and politician José Santos Zelaya takes over state power in Nicaragua. 1897 – Salomon August Andrée leaves Spitsbergen to attempt to reach the North Pole by balloon. 1899 – Fiat founded by Giovanni Agnelli in Turin, Italy. 1906 – Murder of Grace Brown by Chester Gillette in the United States, inspiration for Theodore Dreiser's An American Tragedy. 1914 – Babe Ruth makes his debut in Major League Baseball. 1914 – The US Navy launches the USS Nevada (BB-36) as its first standard-type battleship. 1919 – The eight-hour day and free Sunday become law for workers in the Netherlands.

0 notes

Text

January 06

[1367] Richard II, King of England (1377-99), born in Bordeaux, Kingdom of France.

[1580] John Smith, English explorer and leader of the Virginia Colony (Jamestown), born in Lincolnshire, England.

[1655] Princess Eleonore-Magdalena of Neuburg, Empress of the Holy Roman Empire, German Queen, Archduchess of Austria, Queen of Hungary and Bohemia as the third and last wife of Leopold I.

[1854] Sherlock Holmes, British fictional detective (as created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

[1900] Queen Maria of Yugoslavia (Maria of Romania), Queen Consort of King Alexander I (1922-34), born in Gotha, German Empire.

[1935] Margarita Gomez-Acebo y Cejuela, Tsaritsa of Bulgaria, born in Madrid, Spain.

[1943] Terry Venables, British footballer, manager (Wembley F.C.), and author, born in Dagenham, England.

[1955] Rowan Atkinson, English comedian and actor, born in Consett, County Durham, England.

[1970] Geert Brusselers, Dutch footballer and manager (PSV U-19), born in Eindhoven, Netherlands.

[1970] Julie Chen, American television presenter, born in New York City, New York.

[1974] Daniel Cordone, Argentine football striker, born in General Rodríguez Partido, Argentina.

[1980] Steed Malbranque, French football midfielder, born in Mouscron, Belgium.

[1982] Eddie Redmayne, English actor, born in Westminster, London, England.

[1986] Paul McShane, Irish football defender and PDP Coach at Manchester United, born in Wicklow, Republic of Ireland.

[1991] Nikola Sarić, Danish footballer, born in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

[1592] John Casimir of Simmern, German Prince and regent for his nephew, Elector Frederick IV.

[1799] Frederik, Dutch Prince of Orange-Nassau and General, dies of a fever at 25.

[1852] Louis Braille, French educator and inventor of a system of reading and writing for the blind called Braille.

[1919] Theodore Roosevelt, 26th President of the United States (1901-09), writer, naturalist and soldier.

[1958] Princess Joséphine Caroline of Belgium, dies at 85.

[1993] Elisabeth, Archduchess of Austria, Princess of Liechtenstein, dies at 70.

[2011] Uche Okafor, Nigerian football defender, dies.

#on this day in history#on this day#otdih#otd#football history#football#american history#world history#january#birthdays#rest in peace#january 06#rowan atkinson#julie chen#eddie redmayne#richard ii of england#john smith#sherlock holmes#sir arthur conan doyle#theodore roosevelt#louis braille

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Bohemia Regent. Czech Beer. Premium Lager Pale. 5.0% Обычный сладковатый евролагер. Столовое пиво. 2.5 #BohemiaRegent #CzechBeer #PremiumLagerPale #beer #alcohol #sergejbiohazardovbeer #sergejbiohazardov #быстрыйобзор https://www.instagram.com/p/CmjXpg0sMUi/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#bohemiaregent#czechbeer#premiumlagerpale#beer#alcohol#sergejbiohazardovbeer#sergejbiohazardov#быстрыйобзор

0 notes

Photo

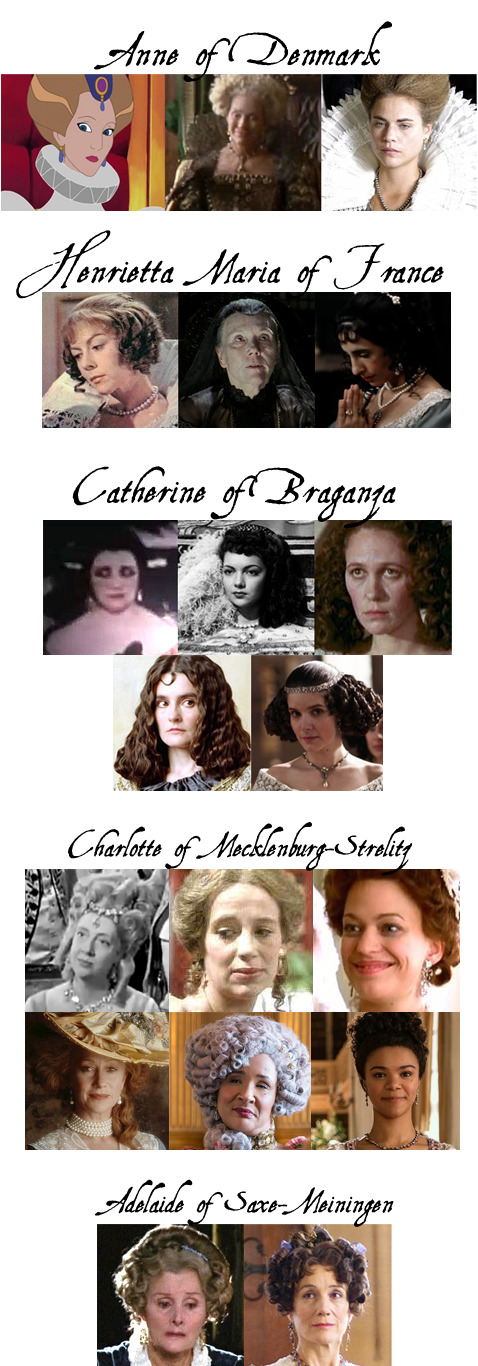

The Queen Consorts of England (minus Henry VIII’s wives) in Film and TV

(No appearances: Matilda of Flanders, Matilda of Scotland, Adeliza of Louvain, Matilda of Boulogne, Eleanor of Provence, Eleanor of Castile, Margaret of France, Anne of Bohemia, Joan of Navarre, Mary of Modena, Caroline of Ansbach, Caroline of Brunswick)

Henry’s wives

Eleanor of Aquitaine, Berengaria of Navarre, and Isabella of Angouleme:

The Devil’s Crown (1978)

Just Eleanor and Berengaria:

Richard the Lionheart (1962)

Just Eleanor and Isabella:

The Adventures of Robin Hood (1955)

Robin Hood (2010)

Robin and Marian (1976)

Just Eleanor:

The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men (1952)

Ivanhoe (1958)

Becket (1964)

The Lion in Winter (1968)

The Legend of Robin Hood (1975)

Robin of Sherwood (1984)

Ivanhoe (1997)

The Lion in Winter (2003)

Robin Hood (2006)

Richard the Lionheart: Rebellion (2014)

Just Berengaria:

Richard the Lion-Hearted (1923)

The Crusades (1935)

King Richard and the Crusaders (1954)

Isabella of France and Philippa of Hainault:

Les rois maudits (1972)

A Cursed Monarchy (2005)

Just Isabella:

Edward II (1970)

Braveheart (1995)

World Without End (2012)

Knightfall (2017)

Isabella of Valois, Catherine of Valois, Margaret of Anjou, Elizabeth Woodville, and Anne Neville:

An Age of Kings (1960)

The Wars of the Roses (1965)

The Hollow Crown (2016)

Just Margaret, Elizabeth, and Anne:

Richard III (1912)

The Tragedy of Richard III (1989)

Just Elizabeth and Anne:

Tower of London (1939)

Richard III (1955)

Tower of London (1962)

Just Isabella

The Tragedy of King Richard II (1970)

King Richard the Second (1978)

Just Catherine:

Henry V (1944)

Henry V (1979)

Henry V (1989)

The King (2019)

Margaret, Elizabeth Woodville, Anne, and Elizabeth of York:

Richard III (1908)

The White Queen (2013)

Just Elizabeth Woodville and Elizabeth of York:

Jane Shore (1915)

Shadow of the Tower (1972)

The White Princess (2017)

The Real White Queen and Her Rivals (2017)

Just Elizabeth of York:

Princes in the Tower (2005)

The Spanish Princess (2019)

Anne of Denmark:

Pocahontas 2: Journey to a New World (1998)

Gunpowder, Treason, and Plot (2004)

The New World (2005)

Henrietta Maria of France:

Cromwell (1970)

The Devil’s Whore (2008)

Catherine of Braganza:

The Glorious Adventure (1922)

Forever Amber (1947)

England, My England (1995)

The Great Fire (2014)

Henrietta and Catherine:

Charles II: The Power & the Passion (2003)

Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

The Young Mr. Pitt (1942)

Prince Regent (1979)

The Madness of King George (1994)

Longitude (2000)

Bridgerton (2020)

Queen Charlotte: A Bridgerton Story (2023)

Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen:

Victoria & Albert (2001)

The Young Victoria (2009)

Alexandra of Denmark and Mary of Teck:

Edward VII (1975)

The Lost Prince (2003)

Just Alexandra:

Lillie (1978)

The Elephant Man (1980)

Mrs. Brown (1997)

All the King’s Men (1999)

Mary of Teck and Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon:

Crown Matrimonial (1974)

Bertie and Elizabeth (2002)

The King’s Speech (2010)

W.E. (2011)

The Crown (2016)

Just Mary:

Edward & Mrs. Simpson (1978)

The Woman He Loved (1988)

Wallis & Edward (2005)

Downton Abbey (2010)

Downton Abbey (2019)

Just Elizabeth:

The Queen (2006)

Hyde Park on Hudson (2012)

A Royal Night Out (2015)

#plantagenets#tudors#stuarts#hanoverians#victorians#windsors#Mary of Teck's numbers surprised me#There are a couple more shakespeare adaptations I didn't dig through properly#Queens on screens

245 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Giovanna d’Austria (1547–78), the youngest of the fifteen children of Emperor Ferdinand I and Queen Anna Jagiellonka of Bohemia and Hungary, was welcomed into Florence by Cosimo I de’ Medici on 16 December 1565 as the bride of his son and heir, Francesco. The duke of Tuscany, who had managed every aspect of Giovanna’s lavish bridal entry down to the smallest detail, took tremendous pride in this marriage to a Habsburg archduchess, the most prestigious match that the Medici had ever made. Cosimo had accomplished much for the Medici since he unexpectedly came to power in 1537, but the union with the Habsburgs came to be considered one of his greatest achievements.

…Although the Medici had indeed increased in stature prior to the marriage, Giovanna was nevertheless of considerably higher rank than her new family and the Habsburgs certainly expected that she would be in a position to exert significant influence in Florence on their behalf. However, her thirteen years as a Medici consort (first as duchess and later as grand duchess) were fraught with tension. Her marriage and status at court were undermined from the outset by ongoing issues outside her control: the hostility between her two families and the constant public presence of her husband’s mistress. Giovanna’s own inability to fully identify with and demonstrate her allegiance to the Medici further contributed to her predicament.

Unable to play the influential role she had expected at the Medici court, Giovanna looked outward, focusing on alternative channels to demonstrate her power and prestige to those at court and to the people of Tuscany: her Habsburg network, her religious patronage of local churches and monasteries, and her highly public pilgrimage to Loreto. A comparison of Giovanna’s difficulties with those of other foreign consorts reveals some of the crucial elements that could make a woman successful or unsuccessful at the court of her marital family. Until quite recently, the limited historiography on Giovanna portrayed her as timid, uneducated, and narrow-minded, and her piety as completely out of place at the dynamic Medici court. In a typical comment on Giovanna, Mary Steegman writes: “her views on life and its conduct were strict, narrow and conventional . . . she was utterly incapable of adapting herself to, or even remotely understanding, a condition of society different from that in which she had been born and bred.”

This traditional view of Giovanna, perpetuated by late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century historians, remained unquestioned well into the twenty-first century. However, important recent scholarship has taken a fresh look at Giovanna by returning to the primary sources, revealing a woman who is much more complex than the nineteenth-century caricature. Recent scholars have also shown great interest in exploring the role of the consort and the different ways in which women could access power and exert influence at court. While a consort might exercise power directly by governing as regent, she also had access to a number of informal channels of influence. However, she could encounter a number of impediments to her attempts to establish herself and, for some women, these obstructions could prove insurmountable.

A consort’s success depended on both factors within her control, particularly her ability to establish her reputation at her new court and form effective patronage ties, and factors outside her control, such as the relationship between her natal and marital families and the presence of a rival at court. In addition, while she might exert influence on behalf of her natal family, it was necessary for her primary loyalty to lie with her husband and his dynasty. Elite women like Giovanna played a crucial role as “unofficial agents” of their natal families at foreign courts. The term “unofficial agent” is used by Magdalena S. Sánchez to describe three Austrian Habsburg women who used court networks, informal influence over the monarch, and traditional women’s roles to promote the interests of their natal family at the court of Philip III. The imperial family relied heavily on informal diplomatic networks involving female relatives who could “bypass official diplomatic channels and could also reach the monarch in private moments.”

Letter-writing was one of the most important tasks women performed in these networks and Giovanna spent a great deal of time corresponding with her relatives, relaying information, receiving and granting requests, and acting as an intermediary between the emperor and the Medici. Giovanna’s father, Ferdinand I, relied on his many daughters to provide him with information on their husbands’ activities and contacts. Indeed, in a letter to Giovanna from an imperial official, she is addressed as “our advocate with His Excellency [Cosimo] in the service of His Caesarean Majesty.” Giovanna’s marriage to Francesco was part of the emperor’s Italian marriage strategy. As she travelled to Italy from her home in Innsbruck in 1565, Giovanna was accompanied by her sister, Barbara, who was to marry the duke of Ferrara. Their sister, Eleonora, had already married the duke of Mantua in 1561.

These three connections brought considerable benefits to both sides: in return for the prestige of an imperial match, the Italian dukes provided significant financial support to the impoverished emperor. Sarah Bercusson has aptly characterized Giovanna’s marriage as “a calculated exchange of rank for wealth.” The three sisters formed but a small part of the vast web of imperial ties stretching across Europe. The Habsburg kinship network had been constructed over centuries as Habsburg women were sent out far and wide for marriage. From their new homes, these women maintained their relationships with the imperial family, participating in an extensive network of patronage and influence.

…With so many children, Giovanna’s father had numerous occasions to play matchmaker. His daughters were brought up in Innsbruck in “a relaxed, yet austere environment” where “they were made to understand at a very early age that they were of royal estate with very special tasks to perform.” However, while his daughters’ marriages were key instruments in Ferdinand’s dynastic strategies, he was also genuinely concerned for their happiness. When assessing a potential match, the emperor considered the character of the potential husband and whether he would be well suited to the daughter in question. According to Paula Sutter Fichtner, “[h]e took the procedure of gaining the consent of his daughters to the unions he contracted for them very seriously” and “those of his children who were clearly unsuited to matrimony he preferred to leave single.”

Despite Ferdinand’s precautions, some of the marriages were unsuccessful. Although the personalities of the individual spouses certainly played a role in the failure of these relationships, dynastic marriages involved many more players than simply the couple in question. Relations between two dynasties were at stake, as was the honor of each. Hostility between the spouses could develop into an international incident. Likewise, enmity between the two families could strain the marriage and put the consort’s loyalties to the test. David Warren Sabean has discussed the tension between a woman’s natal and marital obligations and loyalties in the early modern period, identifying two axes in kinship configurations: descent, moving downward from parents to children, and alliance, which concerns horizontal relations.

Blood was seen as transmitting vital characteristics from parent to child and even binding people unrelated by descent, such as a man and his son-in-law. Women therefore acted as conduits for blood between allies as well as between generations. They acted as mediators between families, but they could also be caught in conflicts between the ascriptive obligations established at birth and the negotiated obligations established by marriage. The tension between vertical and horizontal kinship and women’s roles as mediators between agnatic groups were key issues facing Giovanna and other consorts. Giovanna’s oldest sister, Elizabeth, was sent to Poland in 1543 as the bride of their cousin, the future king of Poland, Sigismund Augustus. However, relations between the two families were tense due to hostility between Ferdinand and the groom’s mother, Queen Bona Sforza, over hereditary claims she was attempting to assert in Italy.

The Polish ambassador reported that Bona, taking her anger out on her daughter-in-law, even tried to prevent the consummation of the marriage. When Ferdinand definitively refused to recognize her inheritance claims, Bona was irate, and made life increasingly trying for Elizabeth. Ferdinand, who “had a good deal of feeling for his daughters especially and sympathy for the situations in which they occasionally found themselves,” sent representatives to Poland to look into the matter, even asking his brother, Charles V, to intervene. The escalating crisis terminated abruptly when Elizabeth died in June 1545. After his second wife died in 1551, Sigismund Augustus again sought a union with his Habsburg cousins; although Ferdinand had misgivings about sending another daughter to Poland, “where political interests were truly compelling, his fatherly scruples occasionally weakened.”

This second marriage was even more unpleasant than the first. Although Queen Bona was no longer a strong presence at court, the couple became completely estranged due to Catherine’s attempts to take an active role in Polish politics, which Sigismund Augustus would not tolerate. In the years since his first marriage, the king’s position in Poland had become increasingly solidified and “the support of the Habsburgs, or rather the appearance of support, was quite indifferent to him.” He refused to live with Catherine, claiming that she was epileptic. This time, Ferdinand sent his son, Maximilian, to Poland to mediate. Like his father, Maximilian was “as concerned about Catherine’s safety and peace of mind as he was about the dynastic implications of her problems in Poland.”

Maximilian, defensive of Habsburg honor and sensitive to insults to the Habsburg name, was outraged at the way his sister was being dishonored—“treated like a whore,” he noted furiously in his dairy. Sigismund Augustus was unsuccessful in his attempt to have the marriage annulled, so the couple remained married. Catherine was eventually permitted to leave Poland after thirteen years of marriage, settling in Linz. Once they arrived at their new courts, Giovanna and her sisters took their places within the imperial kinship network, petitioning each other for favors and building their own patronage ties. In one letter, Eleonora thanked Giovanna for having granted a request: “The recommendation that Your Highness consented to provide some time ago for Messer Costanzo Varolo, public lector of surgery in Bologna, to Cardinal Sforza, was of such benefit to him and I was so pleased with it, that I am writing now to give you the thanks that I owe you.”

In this letter, Eleonora acknowledged the debt of thanks that she owed her sister for the favor rendered. As Kristen Neuschel notes, letters between nobles were “arenas for exchange,” in which intangible courtesies and tangible favors were intertwined and debts were created and repaid: “the language of credit and debit used in their letters reflects the fact that every instance of contact between noblemen was automatically a potential source of recognition or failure of recognition.” Here, Giovanna received valuable acknowledgement and gratitude from her sister in exchange for the tangible favor she performed for her sister’s client, which enabled both sisters to increase their honor and status. The sisters also acted as intermediaries between each other and their respective husbands.

In another letter, Eleonora asked Giovanna to intercede with Francesco in order to obtain the release of a prisoner: Although the error committed by Messer Michele Costa of Genoa, former Chancellor of the University of Pisa, is considerable, he is no less worthy of that pity that moves princes to show mercy . . . I pray Your Highness to intercede for me with the Most Excellent Lord your Prince so that His Excellency, as a favor to me, may show mercy to said Costa. In this letter, Eleonora relied not only on Giovanna’s willingness to grant a favor, but on her capacity to convince Francesco to take action as well. The regular correspondence between Giovanna and her sisters shows just how effective the network of a natal family could be for a foreign consort in establishing patronage ties at her new court.

When they were able to use their connections with each other to obtain favors for others, the sisters increased and reinforced their reputations as valuable patrons with ties to important people. Through their voluminous correspondence, the Habsburg women not only established their own status as patrons, but also engaged in important political work for their dynasty. As Simon Hodson has noted, “in the context of familial and clientage networks, letter-writing must be considered a political activity.” Giovanna’s brother, Maximilian II, often called on her to present his requests to Cosimo and Francesco. In one incident, the emperor sought Medici assistance in putting down an insurgency in the imperial fief of Finale. Giovanna wrote to Cosimo: “I am sending Your Illustrious Excellency a letter from the Emperor . . . I pray you, in your kindness, to let me know your decision on the Imperial Commissioners’ request to send them the aid that they desire.”

Another letter written by Giovanna to Cosimo on behalf of some German students accused of heresy in Siena shows that Giovanna also saw herself as the protector of German residents in Tuscany: The German nation having no one to turn to, if not to me, Your Highness should not wonder that I am acting to recommend it to you as ardently as I can . . . that you write to Rome and pray His Holiness to give the order that those who go to Siena only to learn, and live as Catholics, be left alone to live quietly as they have done up to now. As indicated by these letters, Giovanna saw herself as both an unofficial agent of the emperor and a representative of all German people living in Tuscany.

Like those of her sisters, Elizabeth and Catherine, Giovanna’s marriage was heavily influenced by relations between the Habsburgs and her marital family. In 1564, before Giovanna’s arrival, Cosimo had announced his decision to retire and transfer power to Francesco. Cosimo’s “abdication” merely consisted of the transfer to his son of the tedious day-to-day minutiae of government while reserving for himself the ducal title and supreme authority over his domains. He likely wished to be free to concentrate on more important projects: negotiating the Habsburg marriage alliance and pursuing the grand ducal title. Therefore, even after his so-called abdication, Cosimo remained a key political player and a strong presence in the lives of his son and daughter-in-law.

He seems to have taken on a fatherly role in Giovanna’s life, and their letters to each other express genuine affection. In an exchange of correspondence between them in September 1570, when Giovanna was travelling, Cosimo provided updates on the changes in the condition of her daughters who had fallen ill, and Giovanna was consoled by their grandfather’s loving care. However, Giovanna’s willingness to act on the emperor’s behalf and her continued identification with the Habsburg dynasty, while acceptable in certain situations, such as those described above, could also be problematic for the Medici.

At the bottom of a letter from Giovanna to Francesco, in which she asked him for a loan, Francesco, clearly irritated by her request, accused Giovanna of disloyalty to the Medici: “Anyone who gives 3,000 scudi at a time to [Baron] Prayner, who Her Highness knows to be an enemy of her house, may easily pay her own debts, it being no wonder that she has them, throwing away money in this way . . . So let her sort it out herself.” In the note, Francesco identifies the Medici as Giovanna’s “house,” and the imperial diplomat, Baron Siegfried Preiner, as an “enemy” of that house. As Neuschel points out, sixteenth-century nobles generally used concrete references to action to characterize political activity.

Thus even an abstract term like “enemy,” which would seem to describe a state of being rather than performance of action, refers to active hostility between the Medici and Preiner: “an enemy is in arms and in the field against you, or he is an opponent in a personal feud; he is someone who threatens honor.” The idea that Giovanna may have been giving money to someone Francesco considered an enemy and a threat to the honor of his house shows that years into their marriage Giovanna’s allegiance to the Habsburgs over the Medici continued to be an issue between them. In a moment of outright conflict between her two families, the controversy over the grand ducal title, Giovanna aggravated the situation considerably by taking the side of her brother, Maximilian II.

For some years, the duke had been “badgering Maximilian to confer the title of grand duke on him.” Frustrated by Maximilian’s hesitation, Cosimo turned to the pope. Despite the objections of the other Italian states, Cosimo was raised to the rank of grand duke of Tuscany by papal bull and was crowned by the pope in Rome on 5 March 1570. This completely new title essentially granted the Medici precedence over the other ducal families in Italy. Cosimo’s elevation infuriated both Philip II and Maximilian II, who resented the pope’s encroachment on Habsburg influence in Tuscany. Maximilian went so far as to consider military action against Tuscany, but was unable to gather support. As tense as the situation was, Cosimo’s next action made matters worse.

To the consternation of both his court and his children, he married his mistress, Camilla Martelli. Although Francesco and his siblings quickly managed to mask their anger, Giovanna and her imperial siblings felt personally insulted that an undistinguished Florentine subject would now take precedence over Giovanna at court. The burst of correspondence between Cosimo, Giovanna, and Maximilian concerning the grand ducal title and Cosimo’s marriage is archived together among Cosimo’s papers, beginning with Maximilian’s outraged letter to Giovanna from Prague, which Cosimo had translated into Italian: “This [Cosimo’s coronation] concerns not only me, but all of the Princes and Electors of the empire.”

Maximilian expressed complete bewilderment over the marriage, while pointedly refusing to use Cosimo’s new title: I cannot much wonder what the Duke was thinking when he made such a shameful and unpleasant match, for which he is mocked by everyone. The good Duke must not have been himself. I pray that Your Highness shall not tolerate this brazen woman to be raised up and that you not associate with her. Giovanna forwarded her brother’s letter to her father-in-law. Fuming, Cosimo replied to Giovanna, maintaining (implausibly) that he had only accepted the coronation at the pope’s insistence: “The Pope is such a determined type of person that whether I wanted it or not, he was going to do it . . . I would have liked to have seen what His Majesty would have done in my place.”

In response to Maximilian’s disparaging comments about Camilla, Cosimo’s anger flared: “His Majesty says that I was not in my right mind. To this I reply that when need be I will show him that I am in my right mind.” In closing, Cosimo noted that he found Giovanna’s intervention in the matter highly inappropriate as a member of the Medici family: “I have grown used to handling outsiders, but I wish to be left in peace by those of my own house.” As Francesco had emphasized in his note in response to Giovanna’s request for money, Cosimo stressed that Giovanna was a member of his own house and demanded that she act accordingly. Although deeply offended, Cosimo had to be cautious. His longstanding alliance with the Habsburgs was the basis for much of his power.

He needed Giovanna to resume her usual role as mediator and smooth things over with her brother, but she also needed to identify herself unambiguously with the Medici. The archival file containing this exchange of correspondence also includes an undated draft of a letter from Giovanna to Maximilian. Given its placement among Cosimo’s papers, its conciliatory tone, and its high praise of the Medici, it was likely dictated to Giovanna by her father-in-law and her husband. In the letter, Giovanna attempted to defuse the situation: When I thought I was the happiest woman in Italy, I instead find myself to be the unhappiest alive. I thought I had won a lord and patron for my husband who would give him the protection that befits him, and for Your Majesty a devoted and useful servant. I see that I have done the opposite . . . you seem scornful and offended, through no fault of my father-in-law or husband . . . showing everyone that I am not dear to you and making me live in despair, which I would were it not for the loving treatment and conduct that I receive from everyone here . . . I beg Your Caesarean Majesty may it please you to continue in that good will that you have shown this house in the past . . . otherwise it will be clear to me that I am not loved by you.

In this letter, Giovanna places herself firmly in the Medici camp, praising her husband’s family for their good treatment of her and imploring Maximilian to resume positive relations with them. Giovanna’s letter must have had some effect, as the subject of Camilla and the grand ducal title was dropped. Although relations between the two dynasties remained tense, Maximilian reluctantly recognized the title in 1575 and, “to sweeten the otherwise distasteful bargain . . . Grand Duke Francesco shipped along a hundred thousand badly needed scudi to Vienna.” Although Giovanna was willing to play peacemaker between her families, she would not permit Camilla to take precedence over her or tolerate her presence, flatly refusing to visit the Pitti Palace where Cosimo and Camilla lived.

As a result, the wedding of Cosimo’s son, Pietro, had to be held at the Palazzo Vecchio rather than at the Pitti Palace. Giovanna was apparently successful in keeping her rival away, for the Ferrarese ambassador noted that Camilla was completely absent from all of the wedding festivities. …Despite the tension, Cosimo and Giovanna managed to maintain a respectful, caring relationship. However, her husband was quite another matter. Like her sister Elizabeth, who had been faced with the domineering presence of Bona Sforza, Giovanna had to contend with a direct challenge to her position at court in the form of her husband’s mistress, Bianca Cappello. The favor Francesco showed Bianca made it clear to potential clients at court that establishing a relationship with her would be more rewarding than approaching Giovanna.

Turning to her sisters for consolation and advice, Giovanna complained of her husband’s conduct. After hearing that the spouses had made peace after a quarrel, her sister, Eleonora, expressed relief but warned her of the need to avoid such problems in the future: “[g]overn and control yourself like a wise princess.” A letter from Cosimo shows that Giovanna also turned to him for advice: Any displeasure of Your Highness troubles me greatly because I love you like my own daughter . . . You must not believe everything that Your Highness is told, for courts never lack people who delight in spreading scandals . . . if Your Highness would consider your sisters, perhaps you would be happier with your own condition than you are now, for I know how some of them, and more than one, have been treated . . . Let Your Highness busy yourself with looking after the household, leaving the cares of government to him [Francesco].

As Cosimo’s letter indicates, by early 1572, Giovanna and Francesco’s marriage was under considerable strain and the couple’s marital problems had become the subject of court gossip, hinting at the presence of Bianca Cappello. However, this letter also provides an additional reason for the breakdown between the couple. By advising that Giovanna take care of the household and leave the cares of government to Francesco, Cosimo was insinuating that she had in some way overstepped her role by entering the political realm, as her sister, Catherine, had done in Poland. Cosimo even alluded to the poor treatment that certain of Giovanna’s sisters had received at other courts. Although the sisters in question are not named, Cosimo was certainly referring to the two unfortunate wives of Sigismund Augustus. Elizabeth had died in Poland two years before Giovanna was born, but Catherine’s ordeal was still fresh in the minds of her contemporaries.

It was at this point that Giovanna started planning her pilgrimage to Loreto, which would take place the following year. Although Giovanna’s piety has sometimes been dismissed as yet another indication of her failure to acclimate herself to the less pious Medici court, Sánchez demonstrates that a pious reputation could give a woman great power. She thereby suggests that we expand our view of the early modern court beyond the royal palace to convents and churches in order to explore the ways in which women used religious patronage to exert political influence. Alice E. Sanger has pointed out that while women’s patronage of art and architecture has received extensive attention, devotion and piety were also very powerful tools.

Examining the religious practices of three grand duchesses of Tuscany, including Giovanna, Sanger argues that the “worldly concerns of the grand duchesses were always implicated in their devout activities, while the devotional realm offered sanctioned spaces for political maneuvering.” Giovanna was a contemporary and relative of the Habsburg women Sánchez discusses, and had received similar education and preparation for her role as consort. Still, her piety, which would have been admired at the Spanish court, where royal life revolved around a daily schedule of religious practices with no clear boundary between the political and the religious, was indeed unusual at the Medici court.

From the day she set foot in the city, Giovanna began visiting its churches and monasteries, taking note of what she observed and making suggestions to Pope Pius V: “Since I arrived in this city, I have visited a good part of the monasteries and pious places that are here, including the venerable college of the Jesuits, the location, residence and church of which are so cramped that it is no longer possible for them to remain there.” As this letter suggests, Giovanna championed various causes and practiced her religion publicly in Florence’s “pious places.” While personal devotion was certainly a driving factor in Giovanna’s activities around the city, it also provided her with a platform to become actively and visibly involved in Florentine life.

This letter also demonstrates Giovanna’s particular interest in assisting the Jesuits. Her correspondence contains many petitions to the pope, cardinals, and bishops on behalf of the order in Florence and Siena. In one letter, she thanked the bishop of Grosseto for his support in obtaining a church in Siena for the Jesuits. The following year she wrote to a cardinal to request his assistance in persuading the parishioners of that same church to accept its transfer to the order. During her childhood in Innsbruck, Giovanna and her sisters had enjoyed a great reputation for piety and developed a zealous admiration of the Jesuits. In Innsbruck, the sisters plagued Ferdinand’s court preacher, Jesuit Peter Canisius, with constant demands on his time, while spoiling his brethren with special dishes “for the comfort of those privileged fathers.”

When Giovanna and Barbara left for Italy, they each took a Jesuit chaplain with them. As grand duchess of Tuscany, Giovanna’s persistence helped solidify the Jesuit presence in her husband’s lands. Giovanna’s religious patronage was not limited to the Jesuits. She wrote letters in support of religious causes throughout Tuscany and regularly received requests for assistance. The bishop of Montalcino asked her to intercede with Francesco to obtain a certificate confirming the privileges of the Abbey of Sant’Antimo. The abbess of the convent of the Santissima Annunziata delle Murate in Florence asked Giovanna for charity, given the high cost of wheat, suggesting she ask Francesco for assistance. The abbess of Santissima Annunziata di San Miniato thanked Giovanna for her help in obtaining a confessor for the convent.

Through her visits and letter-writing, Giovanna was able to establish patronage ties with religious communities and exert influence in a way that was impossible for her to do at court—though visible to those at court—while simultaneously developing a reputation for piety among her husband’s subjects. Although Giovanna had been active in religious patronage since her arrival in Florence in 1565, by 1572 her frustration with her lack of influence at court led her to seek out an even more visible way to demonstrate her power and prestige. Her correspondence with Cosimo makes it clear that 1572 was a period of particularly high tension with Francesco that became the subject of court gossip. Her pilgrimage to the shrine at Loreto the following year was Giovanna’s attempt to reassert her status both at court and abroad.

According to legend, the “holy house” where the Virgin Mary lived as a child had been miraculously transported from Nazareth to the eastern coast of Italy in the thirteenth century. When Giovanna arrived in Italy, Loreto was a popular pilgrimage destination with a particular draw for women anxious to conceive. As Giovanna had thus far only produced daughters, she went to the shrine to pray for a son. Sanger notes that Giovanna was the first secular Medici, male or female, to make the pilgrimage, establishing a precedent for later grand duchesses of Tuscany: Christine of Lorraine, who travelled to Loreto in 1593, and Maria Maddalena, who made the journey in 1613. Although Giovanna was certainly motivated by sincere piety, this was no private act, but a magnificent display of prestige “designed to spectacularize her devoutness, rather than promote an image of humility.”

Indeed, her vast retinue included 430 horses, eighty carriages, thirty liveried guards, twelve pages, and twelve ladies dressed in black. Giovanna’s entourage travelled slowly through Cortona, Perugia, Foligno, and Macerata, taking two weeks to reach Loreto. She received a flood of correspondence from the elites in those areas, welcoming her and extending invitations. Pope Gregory XIII, who honored Giovanna by paying her expenses for the pilgrimage, assigned an escort to accompany her through the Papal States. She was offered hospitality by the duke of Urbino and, when she declined, he sent an ambassador to convey his regards to her in person in Loreto. Ambassadors were also sent out by the city of Perugia to accompany her to their city, where she was warmly welcomed.

As she reported in a letter to Francesco, once she reached Loreto she spent most of her time praying in the chapel, but was also kept quite busy by visits with various dignitaries. In addition to displaying her status, this significant moment in Giovanna’s life enabled her to forge a connection with the shrine that lasted for the rest of her life, as shown by the correspondence and gifts exchanged between Giovanna and the clerics at Loreto over the years. During her visit, Giovanna presented several gifts to the shrine, including a silver crucifix sculpted by the Medici court sculptor Giambologna with her name inscribed on it. When her son Filippo was born, a celebratory mass was sung at Loreto, in which furnishings previously donated by Giovanna were used. A year after her pilgrimage, she was informed that a portrait of her in Loreto was attracting crowds of visitors.

Giovanna came to be so associated with the shrine that when an official in Livorno wrote to inform her that a Medici ship had been saved from disaster at sea, he attributed this miracle to the Madonna of Loreto. Where Giovanna’s visits and correspondence on behalf of local churches and monasteries in and around Florence had made her visible to Tuscans, the journey to Loreto expanded her reputation beyond the borders of Tuscany. Having encountered significant obstacles to her efforts to establish patronage ties and exert influence at the Medici court, Giovanna turned to religious patronage in order to carve a space for herself outside the court that would demonstrate her influence and status to those inclined to underestimate her.

The number of petitions she regularly received from religious communities is evidence that she came to be held in high regard as a successful patron of religious causes. Despite her achievements in these areas, Giovanna’s position at court remained precarious, taking a turn for the worse after Cosimo died in 1574. Shortly thereafter, she failed once again to produce a male heir, instead giving birth to her sixth daughter, Maria, the future queen of France. The following summer, Francesco’s brother, Piero, strangled his wife, Eleonora di Garzia di Toledo. A few days later, Francesco’s sister, Isabella, died under mysterious circumstances while on a hunting trip. Giovanna was shocked by the sudden deaths of the two most prominent women at court after herself. When Bianca gave birth to Francesco’s son a few months later, Giovanna became deeply demoralized and desperate to leave Florence.

As in the case of Giovanna’s sisters, the mistreatment of a Habsburg woman was received as a serious affront to Habsburg honor. Giovanna’s brother, Archduke Ferdinand of Tyrol, was incensed and considered removing her forcibly from Florence. However, when Francesco complained to the new emperor, Rudolf II (Maximilian II having recently died), of the archduke’s accusations, Ferdinand was forced to back down. A document sent by the archduke to the emperor and translated into Italian for Francesco reveals the extent of the antagonism between Giovanna’s husband and her brother. The archduke admitted that he was deeply distressed: That his sister was so mistreated and held in such little respect by her consort while, conversely, Bianca was raised up, even though everyone knows that she [Giovanna] is the sister of His Serenity [Ferdinand] and everyone knows the circumstances and qualities of Bianca, who is nevertheless held in greater regard than an Archduchess of Austria.

However, the Medici alliance and the financial support that came with it were too important for the emperor to risk. Powerless to act without Rudolf ’s approval, Ferdinand gave way: “If the Prince of Florence does not wish to love and treat his [Ferdinand’s] sister with that love and marital loyalty that is befitting, we Austrian Princes cannot in good conscience do other than commit everything to God.” Although Cosimo had tolerated Giovanna’s attempts to exercise control over certain aspects of her life at court, as in the case of her exclusion of Camilla, and although Maximilian had been responsive to his sister’s complaints due to his own problems with the Medici, this incident demonstrates that without the protection of Cosimo and Maximilian, Giovanna was isolated.

After six daughters, she finally gave birth to a son in 1577, one year before dying from complications in childbirth. Just a couple of months after her death, Francesco married Bianca. The case of Giovanna d’Austria sheds light on the obstacles confronting foreign consorts as they navigated new relationships with their marital families while attempting to remain loyal to their natal families. Her example and those of her sisters, Catherine and Elizabeth, indicate the dangers posed by a strained relationship between two dynasties and the usurpation of the consort’s position at court by a rival female figure. Giovanna’s own reluctance to display unwavering allegiance to the Medici further exacerbated her situation, demonstrating the crucial nature of a complete transfer of loyalty from natal to marital family.

…Although she was never able to assume the prominent political role she considered to be her right as a Habsburg princess and Medici consort, Giovanna’s correspondence reveals that she was far from resigned to the obstacles she encountered, looking outside the Medici court for alternative ways to exercise power. Her network with her sisters provided her with opportunities to bolster her status and potential to act as a patron by exchanging favors with other elite women. Her piety, once considered by scholars to be a weakness, proved instead to be a fruitful source of patronage and influence: in particular, her pilgrimage to Loreto represented an impressive display of prestige that attracted the attention of her contemporaries and inspired later grand duchesses.”

- Catherine Ferrari, “Kinship and the Marginalized Consort: Giovanna d’Austria at the Medici Court.” in Early Modern Women

25 notes

·

View notes