#Bianliang

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

.

#siri how do i purge those fictional gay ppl from my mind QUICK!!!!!#watching a kdrama with friends & there’s a whole cheesy montage abt the first snow#and how ppl who like each other fall in love & will be together forever if they watch the first snow#now do you think i’m feeling normal about this?#do you think i’m doing okay?#when the first snow of the year 1355 fell when ouyang asked esen to come to bianliang with him???#when esen’s death became truly inevitable?? and ouyang had snow in his hair??#spc when i fucking gET YOU#that honey it’s 4 pm time for your cock&ball torture meme but it’s me @ myself opening a new canvas#send post

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

what do you people think. if Esen was alone when Ouyang returned from Bianliang. would they have kissed

#i can only imagine them kissing and Ouyang going ''come back to bianliang with me'' in between kisses in a true homme fatale manner à la WBX#me?? starting a new WIP at 4 am??? it's more likely than you think#i've been relistening to That Almost-Kiss scene on audiobook and i'm unwell now thinking abt what could have been if Esen didn't talk#not that a kiss alone would have fixed them but it would have been something#and after that their next scene is ''come to bianliang with me''#and apart from everything going on there it's so evident how badly Ouyang wants to be kissed and touched again#''He stopped in front of Esen. Close enough to touch.'' he didn't need to do that. he did that on purpose.#that feeling when you're actively flirting with the guy you've been in love with for years while also inviting him to be killed#how am i supposed to recover from that

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Riverside Code at Qingming Festival ( 清明上河图密码 ) : Qīngmíng shànghé tú mìmǎ Cultural Meta Masterpost

All the images are taken from show's official Weibo

Riverside Code at Qingming Festival is our newest Big Chinese Period Drama, as in actual proper historical drama. The premise is a series of mysterious murder cases that happen alongside the Bian river that flows across the capital of Nothern Song Dynasty, Bianliang, during the time of Qingming Festival, at the same time as the painter Zhang Zeduan happened to be drawing the world-renowned painting Along the River During the Qingming Festival.

In other words, the show's based on a novel that was inspired by the said artwork and the possible intrigues that the hundreds of people captured in that painting must've undergone during that time, long long ago.

The show was officially announced on 2023. 10. 18, and had been relentlessly promoting its content, how much research and historical reproduction and replications and all that went into the project. The episodes themselves (which you can watch here for free with Eng subs) have an ending segment called Song Dynasty Encyclopedia, to educate the viewer on the significance of the painting and other Song Dynasty trivia.

And rightfully so, if you watch this short BTS video you'll realise what a MASSIVE project and labor of love this was and they should be proud of it and boast about and promote their work to heaven and back.

youtube

And as always, I dove headfirst into all the meta crumbs I could get my hands on and am gonna compile them here and share with whomever else is interested! 😁

Mind, the translations might not be super smooth, my Chinese is but elementary but I'll try to provide more external links to supplement the posts so you can read from people who know better!

.

1. Nuo Opera

2. Restoration of Bianjing City based on Zhang Zeduan's Painting

3. Nightlife at Bianjing City

4. Food

5. Posters

6. Fashion

7. Miscellaneous

.

More posts by me

#Riverside Code At Qingming Festival#cdrama#chinese drama#chinese history#chinese art#清明上河图密码#Qīngmíng shànghé tú mìmǎ#清明上河图#Along the River During the Qingming Festival#Qīngmíng Shànghé Tú#Youtube

54 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi!!! For the wip game: Ouyang fix it with Prince of Radiance therapy and/or MCS is not Lin Shu please

Fond as I am of "Mei Changsu actually is a would-be imperial garden designer" of the two choices this has to be "Ouyang fix it with Prince of Radiance therapy". This is almost the first TRE fic idea I ever thought of, but because it's longer it's had to wait to be written and exists in a series of lengthy jottings and hard-copy notes I haven't typed up yet. The premise is that a glory-seeking Mongol captain takes the Prince of Radiance hostage on the morning of the battle of Bianliang, everyone takes this as an omen, and Ouyang finds himself having to change his plans. I wanted a situation in which Ouyang was with someone who has the Mandate and a vested interest in telling him about the ghosts, so he ends up in this overwhelming family reunion mediated by a nine-year old. (And then things get fixed for everyone except Zhu. Sorry, Zhu. You'll have to win the Empire the hard way, but I'm sure you will.)

- You know who they are.

He knew. He had always known. Their mouthless voices were a roar in his head, their breath sucked all the air from his lungs. He was on his knees before them, his accusing ancestors, whom he had failed at every turn.

Then the child’s shrill voice was shouting: ‘Stop it! Stop it! There are too many of you’ and suddenly the ringing in his head was silenced, the boy beside him broken out of his terror and standing quite calmly listening, and then at his own side, tugging at him.

- Get up, get up. Please. They want you to. No, properly. The boy heaved at his arm. You’re a general and their son. You should stand.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

What kills me is that throughout this whole book Esen keeps telling Ouyang, "what do you want? I'll give it to you." And he means it so genuinely!

But Ouyang doesn't ask for anything and keeps not asking him for anything, so Esen just has to guess and give him things anyway, until Ouyang says, "I want you to come to Bianliang with me (so I can kill you)." And Esen goes! Because he couldn't even conceive of Ouyang betraying him. Then Ouyang says "I want you dead" and Esen gives him that too, by walking into his sword

Except as much as Ouyang wants Esen to die, he equally wants an Esen who truly sees and understands him. But he can't have that because his desire and the fate he chose and keeps choosing are at odds, and Esen can't give him that either because doesn't fully see Ouyang. He has all the love and affection for Ouyang but it isn't enough because he doesn't understand Ouyang's suffering. Even as Esen wants to give Ouyang everything, he keeps brushing past the fact that Ouyang once had a family that his family killed, that he holds so much shame and self-hatred as this non-man being

Ouyang and Esen are a tragedy that couldn't end any other way, that was only made a tragedy in the first place because of love, and I think that's beautiful

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Brocade Mouse Royal Cat Nine Deep Blood Wolf (2021)

The Brocade Mouse Royal Cat Nine Deep Blood Wolf (2021) 720p HDRip Hindi ORG Dual Audio Movie ESubs [700MB] IMDB Ratings: 5.2/10Directed: Francis NamReleased Date: May 22, 2020 (China)Genres: Action ,Comedy, Mystery, ThrillerLanguages: Hindi ORG + ChineseFilm Stars: Zheng Gong, Minghan He, Tat-Wah LokMovie Quality: 720p HDRipFile Size: 691MBStoryline, Terrible things are afoot in Bianliang City.…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Jarrón

siglo XII

China

sin información sobre el/la creadorx

Tipo de objeto

jarrón

Medio

gres pulido con recubrimiento de engobe bajo esmalte

Dimensiones

42.9 cm

Escuela, estilo

cerámica Cizhou

Proveniencia, adquisición

The Cleveland Museum of Art, Compra del Fondo J. H. Wade

Condición, partes

buen estado, una parte

Eventos y lugares históricos asociados

China, dinastía Song del Norte (960-1127)

La dinastía Song (960-1279) fue, desde el punto de vista cultural, la época más brillante de la historia imperial posterior de China. Fue una época de grandes cambios sociales y económicos, y determinó en gran medida el clima intelectual y político de China hasta el siglo XX. La primera mitad de esta época, en cuyo momento la capital estaba situada en Bianliang (la actual Kaifeng), se conoce como el periodo Song del Norte.

Los inicios de la dinastía Song del Norte fueron testigos del florecimiento de una de las expresiones artísticas supremas de la civilización china: la pintura de paisajes monumentales. Los pintores reclusos del siglo X, que se retiraron a las montañas para huir de la agitación y la destrucción ocurridas al final de la dinastía Tang (618-907). Descubrieron en la naturaleza el orden moral que habían encontrado ausente en el mundo humano.

Una importante consecuencia de la unificación política de los Song tras el periodo de las Cinco Dinastías (907-960), devastado por la guerra, fue la creación de un estilo distintivo de pintura de la corte bajo los auspicios de la Academia Imperial de Pintura. Aunque mantenía que el propósito fundamental de la pintura era ser fiel a la naturaleza, el emperador Huizong (r. 1100-1125) trató de enriquecer su contenido mediante la inclusión de resonancias poéticas y referencias a estilos antiguos.

Fuentes

The Met, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Clasificación (palabras clave)

cerámica, jarrón, flora, cizhou, gres

Colecciones

Cerámica Cizhou

Localización física y digital

The Cleveland Museum of Art, número de acceso 1948.223

https://bit.ly/3huWltp

Sustrato, número de serie MQ3

https://bit.ly/2SY6Co9

Diseño asociado

https://bit.ly/3dR59az

Bibliografía y más

https://bit.ly/3d5rCQw

https://bit.ly/2Skh350

#jarrón#china#siglo XII#XII#gres#esmalte#cerámica#cizhou#cerámica cizhou#CMA#dinastía Song#Bianliang#paisaje#naturaleza#resonancias poéticas#flora#historia digital#historia pública#digital history#public history

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Random Stuff #14: Cats in China--History (Part 2)

(Link to Part 1)

(Warning: Very long post ahead with multiple pictures!)

Cats Becoming Pets

In the book Dreams of Splendor of the Eastern Capital (《 東京夢華錄 》), a memoir by Meng Yuanlao/孟元老 about life in the then “Eastern Capital” or Bianliang/汴梁 (today known as Kaifeng/开封, located in Henan province) in Northern Song dynasty (960 - 1127 AD), there was a section called “Miscellaneous Goods”, which revealed that there were special street vendors who sold horse feed, dog food, and of course, cat food and cat treats:

“If you kept horses, there were two people who sold hay daily; if you kept dogs, there were dog food being sold; if you kept cats then there were cat food and small fish”. (“若養馬,則有兩人日供切草;養犬則供餳糟;養貓則供貓食並小魚”)

Another book that shed light on this change in more concrete terms is Fleeting Dreams of Splendor (《夢粱錄》)--which as you can probably guess from the title, is a memoir modeled after Dreams of Splendor of the Eastern Capital, this time about life in Southern Song dynasty (1127 - 1279 AD) capital city Lin’an/臨安 (today known as Hangzhou/杭州, located in Zhejiang province). In the book it was mentioned that people in the capital kept white or yellow long haired cats, called “lion cats”/獅貓, which couldn’t catch mice and were only kept for their looks, or in other words, these cats had become actual pets:

“People of the capital kept cats to catch mice, and the cats have long hair. Those that were white or yellow were called ‘lion cats’, these cats could not catch mice and were kept because they looked beautiful”. (“貓,都人畜之捕鼠,有長毛。白黃色者稱曰「獅貓」,不能捕鼠,以為美觀”)

During Song dynasty, folk customs also developed around cat adoption. Cat adoption, called pin/聘 or na/納, was treated like a “wedding” of sorts, complete with a “bride price” and a “marriage certificate” contract/契. The “bride price”, of course, was paid to the family that the cat came from, and usually took the form of some salt (this act is called ”bringing salt”/裹鹽; historically salt is a valuable commodity) or some small fish skewered on a willow branch (called “buying fish and skewering with willow”/買魚穿柳 or simply “skewer of willow”/穿柳). The contract, however, had quite a mysterious air about it and vaguely resembled a Daoist talisman:

^ Template of a cat contract, from Yuan-era (1271 - 1368 AD) book Newly Published Reference on Ying Yang and Selection of Dates/《新刊陰陽寶鑑剋擇通書》. Top says “Cat Contract”/貓兒契式. Content consists of a drawn picture of the cat in question at the center, and the terms of the contract written in a counterclockwise order that spiraled outwards from the picture of the cat, which read:

“A cat is Black Spots¹, it used to live before the bodhisattvas of the West, Sanzang² brought it home with him, and it has since been protecting Buddhist scriptures among the people. The Offeror is Moujia³ , who is selling (this cat) to a certain neighbor. All three parties⁴ has agreed upon the price of __, so __ will be returned as the contract finalizes. May the Offerer become as wealthy as Shi Chong⁵, and as long-lived as Peng Zu⁶. (From now on, the cat) Must patrol the grain storage diligently, and must catch rat thieves without slack. (The cat) Must not harm the chickens and other livestocks, and must not steal any sort of food. (The cat) Must guard the home day and night, and must not wander to the east or west. If (the cat) breaks these terms and wanders off, it shall be punished in the courtyard. __ year __ month __ day, Offeror __.”

The foot of the contract read:

”To evaluate a good tabby cat: there must be stripes on the body, and the stripes on the limbs and tail must be just right”⁷

“King Father of the East⁸ see to it that (this cat) does not wander south”

“Queen Mother of the West⁸ see to it that (this cat) does not wander north”

“Received on a day blessed by the Eminent Benefactor of Heavenly Virtues and Eminent Benefactor of Lunar Virtues⁹”

“Returned on a day blessed by the Eminent Benefactor of Heavenly Virtues and Eminent Benefactor of Lunar Virtues”

Notes:

“Black Spots”/黑斑: placeholder cat name.

Sanzang/三藏 refers to Xuanzang/玄奘, as in the real life inspiration of the character Tang Sanzang/唐三藏 in Journey to the West. It was widely believed that domestic cats had came to China from India with traveling Buddhist monks, and that they were protecting the scriptures from damage by rodents.

“Moujia”/某甲: placeholder human name.

“Three parties”: Offeror, Offeree, and Witness.

Shi Chong/石崇 was an extremely wealthy official during Western Jin dynasty (266 - 316 AD) who loved to compete with others over who was the wealthiest.

Peng Zu/彭祖 is a figure in legend and a Daoist immortal who had lived for 700 years according to legend.)

This is part of the practice of evaluating cats based on looks, called xiangmao/相貓.

King Father of the East/東王公 and Queen Mother of the West/西王母 are gods of Yang and Yin respectively.

Eminent Benefactor of Heavenly Virtues/天德貴人 and Eminent Benefactor of Lunar Virtues/月德貴人 are deities representing celestial objects, and are part of the Four Pillars of Destiny/四柱命理 concept in Chinese astrology, where basically different days and times are presided over by different celestial objects and therefore different gods. A day that is blessed by both of the aforementioned Eminent Benefactors is considered to be a very auspicious day.

As a cat owner, I could most definitely feel the helplessness and desperation emanating from this contract. Invoking deities in the hopes that the cat will do its job, not destroy stuff, and not simply run away......I’m sure many cat owners throughout the ages and across the world could sympathize with this sentiment. The special emphasis that was placed on keeping the cat from running away was probably because back then, people lived in residences that consisted of buildings surrounding a courtyard in the middle (for example, a siheyuan/四合院), so it was extremely easy for cats to run out of the residence and become lost.

Anyways......back to history.

Song-era poets wrote many poems about cats, and both Song-era and Yuan-era painters painted many works about cats (which I will cover in my next posts!). At the same time, cats were painted in Song-era tomb murals along with sparrows as a sign of longevity, since cats are māo/猫 and sparrows are què/雀, and when said together they sound like the word mào qí/耄耆, which means “elderly people”.

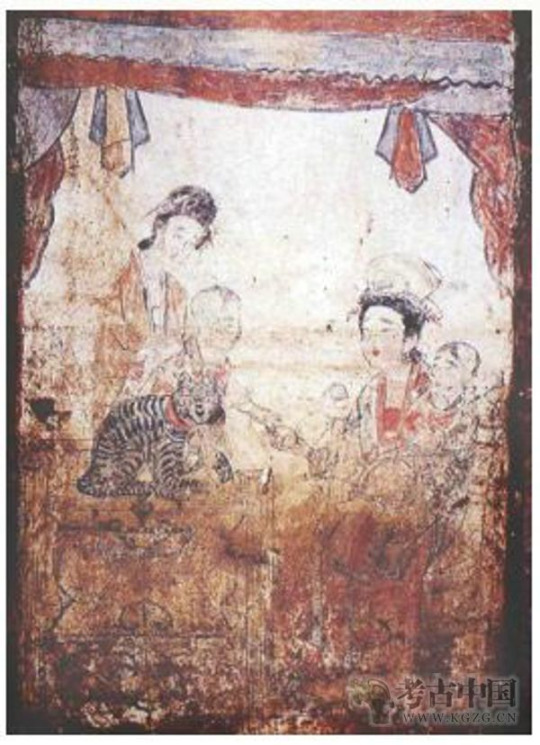

^ Tomb mural depicting a tabby cat with a sparrow in its mouth. From a Northern Song-era tomb discovered in Dengfeng, Henan.

Ming dynasty (1368 - 1644 AD) emperors were also big-time cat lovers. Of note were Emperor Xuanzong of Ming/明宣宗 (personal name Zhu Zhanji/朱瞻基), who painted cats, and Emperor Shizong of Ming/明世宗 (better known as Jiajing Emperor/嘉靖帝), who reportedly loved his cat Frosty Brows/霜眉/Shuangmei (I swear this name sounds a lot more artsy in Chinese) so much that he bestowed the title of Qiulong/虯龍 (note: Qiulong is a type of Chinese dragon that is either defined as horned or hornless depending on the source) upon it, and when Frosty Brows died, he ordered a tomb be constructed just for his cat, then ordered high-ranking officials to write eulogies for Frosty Brows:

“During Jiajing Emperor’s reign, there was a cat in the palace whose fur was slightly blue-ish except the glowing white brows, so it was named ‘Frosty Brows’. This cat understood His Majesty well, and when His Majesty went somewhere in the palace or visited a consort, it would walk ahead and lead the way. While His Majesty slept, it would stay nearby. His Majesty adored it the most. When it died, His Majesty ordered it be laid to rest at the shady side of Mt. Wansui (today called Jingshan/景山), and a stone stele was to be erected marking its grave as ‘The Grave of Qiulong’”. (嘉靖中,禁中有貓,微青色,惟雙眉瑩潔,名曰“霜眉”。善伺上意,凡有呼召或有行幸,皆先意前導。伺上寢,株橛不移。上最憐愛之。後死���敕葬萬歲山陰,碑曰‘虯龍塚’)

-- Old Rumors Under the Sun, “Within the Palace of Ming Part 3″/《日下舊聞考·宮室·明三》

“Later when a lion cat of the Palace of Eternal Longevity died, His Majesty grieved and ordered it be laid to rest at the shady side of Mt. Wansui in a coffin of gold, then ordered the senior officials to write eulogies and a funeral ritual be done, so the cat’s soul may achieve transcendence. However because the prompt seemed awkward, most of the senior officials could not perform at their usual levels, only the Scholar of Rites Yuan Weiwen came up with such words as ‘the lion metamorphosed into a dragon’, which delighted His Majesty”. (“最後西苑永壽宮有獅貓死,上痛惜之,為製金棺葬之萬壽山之麓,又命在直諸老為文,薦度超升。俱以題窘不能發揮,惟禮侍學士袁煒文中有「化獅成龍」等語,最愜聖意”)

-- Compiled Rumors of Wanli Era, Chapter 2/《萬曆野獲編·卷二》

^ A Nebelung cat (image source). According to the description above, Frosty Brows probably looked like this cat but with white markings above the eyes. RIP Frosty Brows, you shall be remembered.

Of course, Frosty Brows wasn’t the only pet cat in the palace. According to Moderate Records/《酌中志》, a book that’s mostly about life in Ming-era imperial palace (which is the same as the Palace Museum today), there was a special place called the “House of Cats”/貓兒房 that employed 3-4 servants just to take care of the cats that were favored by the emperor. These cats even had titles and nicknames: un-neutered male cats were called xiaosi/“小廝”/”lads”, neutered male cats were called laoye/”老爺”/“old men”, female cats were called yatou/”丫頭“/”gals”, and cats with titles were called maoguanshi/”貓管事”/“cat butlers” .

Speaking of royal kitties that left their names in history, Emperor Qianlong (1711 - 1799 AD) of Qing dynasty commissioned a series of paintings of his cats from the court painter and Jesuit missionary Ignatius Sichelbart (also known by his Chinese name 艾啟蒙/Ai Qimeng), and this series of 10 paintings were collectively known as 《貍奴影》, or “Cat Images” (li/“貍” or linu/“貍奴” are both archaic names for cats). Here is a Douyin video of these 10 paintings and the names of these 10 royal felines, translation courtesy of @rongzhi.

The Ins and Outs of Feline Ownership

By Qing dynasty (1636 - 1912 AD), there were two encyclopedia-like books specifically about cats, called The Compendium About Cats/《貓苑》 and The History of Cats/《貓乘》 respectively, which were extensive compilations of records and mentions of cats from older texts, including everything from folktales about cats to cat behavior to how to take care of cats, which served as guides for new cat owners back then. Although cat owners today have much more reliable and scientific sources on how to take care of cats (***Please keep in mind: this post is for fun! If you have any questions regarding the health of your cat, please ask your local veterinarian!***), books like these still provide an interesting glimpse into how cat owners of old went about taking care of their cats. Here I will be presenting a few passages from The Compendium About Cats/《貓苑》 that I found to be pretty cool or interesting:

How people used to bring cats back home and litter train them:

“The way to adopt cats: use a dou¹ or a bucket, and carry it in a cloth sack. Once you reach the home of the previous owner, ask them for a single chopstick, then put both cat and chopstick in the bucket inside the sack to bring them back home. Should you encounter potholes on the way back, you must fill the pothole with rocks before passing over it. Upon arriving back home, take the cat along to worship the household stove god and greet the resident dog. When you are done, take the chopstick and stick it in a mound of dirt in the yard, then tell the cat to never urinate or defecate inside, but still allow the cat to sleep on the bed. This way the cat will not run away”. (“納貓法,用斗或桶,盛以布袋,至家討著一棍,和貓盛桶中攜回。路遇溝缺,須填石以過,使不過家,從吉方歸。取貓拜堂灶及犬畢,將箸橫插於土堆上,令不在家撒屎,仍使上床睡,便不走徃”)

How people thought neutering changed behavior:

“Male cats must be neutered to blunt its might, so their toughness may be softened, and they will soon become plump and friendly”. (“公貓必閹殺其雄氣,化剛為柔,日見肥善“)

What to feed cats and what not to feed cats:

“Cats will grow sturdy when fed eel, and will grow plump when fed pork liver. However if cats are fed too much meat broth, it will give them intestinal issues”. (“猫食鳝则壮,食猪肝则肥,多食肉汤则坏肠”)

“Catnip”:

“Cats will become inebriated after eating mint²”... “Mint is the alcohol of cats, as such the leaves are fresh and relaxing”. (“貓食薄荷則醉”...“貓以薄荷為酒,故葉清逸”)

Treatment for fleas:

“When a cat has fleas, mash up peach tree leaves and chinaberry tree roots, boil the paste into a warm brew and bathe the cat in it to kill the fleas; otherwise rubbing camphor tree shavings over the cat also works”. (“貓生虱,桃葉與楝樹根搗爛,熱湯泡洗,虱皆死,樟腦末擦之亦可”)

Notes:

Dou/斗 (here pronounced dǒu), was historically a type of container that was originally for wine, and then became an apparatus used to measure volume (particularly for grains), so dou also doubled as a unit of volume. This unit of volume can be traced back to at least the Warring States period (770 - 221 BC), but is considered archaic today and could only be found in chengyu and other sayings that originated in history (ex: 升斗小民, “sheng and dou commoners”; since both sheng and dou are relatively small units of volume that ordinary people used in day-to-day life, this chengyu was and is still used to imply “ordinary people”).

“Mint” or “薄荷” here is likely just a species of mint. However, catnip (Nepeta cataria) is a member of the mint family, and its native range seems to span much of Eurasia, including parts of China, so it’s unclear exactly which member of the mint family this text is referring to.

Cats in the Age of the Internet

Thanks to scientific and technological advances, many people no longer adopt cats to keep rodents away, but keep them solely as companions. However, being our feline overlords, cats require a lot of affection, attention, service, and commitment from their humans, thus giving rise to the playfully self-mocking terms of "official(s) of poop-scooping”/铲屎官/chanshiguan and “slave(s) of cat(s)”/猫奴/maonu, while cats are called “cat master(s)”/猫主子/maozhuzi due to their seemingly volatile moods and behavior. People even imagined that cats were aliens from another planet called the “Planet Meow”/“喵星” who came to Earth to conquer humans with their cute appearance, thus giving rise to the term “Meowish”/“喵星人”, meaning “inhabitant of Planet Meow”. A cat who raises its hind leg up straight to lick its backside is described as “sending signals back to the mother planet (Planet Meow)”, and a common euphemism for a cat passing away is “(the cat) has returned to Planet Meow”.

^ An inhabitant of Planet Meow sending signals back to its mother planet.

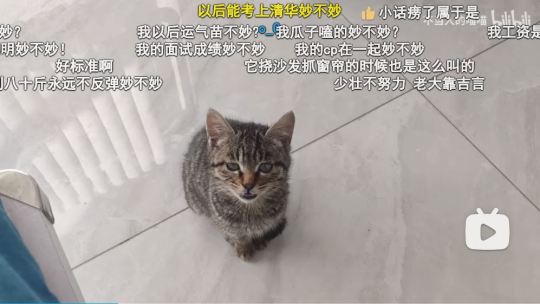

Another common internet slang for the act of kissing, sniffing, or hugging a cat out of adoration is “sniffing cat”/“吸猫”/ximao. As some might notice, the term subtly and playfully draws a parallel between the addictive aspect of cuddling with a cat and the addictiveness of illicit drugs. Finally, because 喵 (miāo), the character for “meow”, is a homophone of 妙 (miào), the character that can mean “great”, on videos where there are cats meowing clearly, you can see barrage comments from many people asking questions like “how is my exam going to go” or “how is my job interview going to go”, as a playful way of wishing for things to go smoothly in the near future.

^ Some examples of these barrage comments, with people asking “how is my job interview score”, “how is my luck in the future”, “am I going to be accepted into Tsinghua University”. Video from Bilibili.

And that is all for the history of cats in China! In Part 3 and Part 4 I will cover famous paintings about cats and poems of cats, and these posts will be coming out within the next two weeks, stay tuned!

312 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Heroic Ones 13 พยัคฆ์ร้ายค่ายพระกาฬ (1970) พากย์ไทย

ภาพยนตร์ ยูกิโอะ มิยากิ แก้ไขโดย เชียง ซิง-ลุง ดนตรีโดย หวังฟู่หลิง จัดจำหน่ายโดย Shaw Brothers Studio วันที่วางจำหน่าย 14 สิงหาคม 1970 เวลาน 121 นาที ประเทศ ฮ่องกง ภาษา แมนดาริน ตัวอย่างหนัง The Heroic Ones 13 พยัคฆ์ร้ายค่ายพระกาฬ (1970) https://youtu.be/2xgHLNnbf1g เนื้อเรื่อง ในยุค 880 ของจักรวรรดิจีน ราช สำนัก ราชวงศ์ถังไม่สามารถควบคุมอาณาจักรของตนได้อย่างมีประสิทธิภาพอีกต่อไป และเมืองหลวงของฉางอาน เมืองหลวงของประเทศจีน ดูหนังออนไลน์ ถูกกองทัพต่อต้านรัฐบาลของ Huang Chao ไล่ออก Li Keyong หัวหน้าเผ่า Shatuoที่ภักดี��่อสาเหตุ Tang ได้นำกองกำลังของเขาไปปราบปรามการกบฏ นายพลทั้ง 13 นายของเขา ซึ่งเป็นลูกชายบุญธรรมทั้งหมดของเขา ช่วยขับไล่ Huang ออกจากเมืองฉางอาน แม้ว่าความแตกแยกระหว่างพวกเขาบางคนก็ชัดเจนขึ้นเรื่อยๆ ในกระบวนการนี้ หลังจากชัยชนะ Li Keyong ยอมรับคำเชิญไปงานเลี้ยงที่ เขต Bianliang ผู้ว่าการทหาร Zhu Wen โดยไม่รู้ว่ามันเป็นกับดักที่จะลอบสังหารเขา Read the full article

0 notes

Link

Lin Chong (Hanzi: 林冲, Pinyin: Lín Chōng), memiliki nama panggilan Kepala Macan Tutul, adalah instruktur pelatihan kemiliteran 800.000 pengawal kekaisaran di Bianliang, ibu kota Dinasti Song Utara (sekarang Kaifeng, Henan). Dia seorang yang jujur, lurus, dan disiplin. Suatu hari, Lin Chong membawa istrinya ke kuil yang ada di gunung untuk bersembahyang. Dalam perjalanan, Lu Zhishen (Hanzi: 鲁智深, Pinyin: Lǔ Zhìshēn), seorang biarawan bunga, memainkan tongkat Huntie Chan seberat 60 pon. Semua orang bertepuk tangan, dan Lin Chong juga tertarik untuk menonton. Kemudian, Lu Zhishen dan Lin Chong, menjadi teman pada pandangan pertama dan menjadi saudara. Pada saat ini, pelayan istri Lin Chong, Jin’er, buru-buru datang untuk melaporkan bahwa Nyonya Lin dicegat oleh penjahat di jalan. Lin Chong buru-buru mengucapkan selamat tinggal pada Lu Zhishen dan pergi ke kuil untuk mengejar gangster itu. Ketika Lin Chong memukul dan menangkap penjahat, dia tahu bahwa pria itu adalah Gao Yannei (Hanzi: 高衙内, Pinyin: Gāo Yánèi), anak angkat dari atasan langsungnya, Gao Qiu (Hanzi: 高俅, Pinyin: Gāo Qiú). Kelompok Gao Yanei mengetahui bahwa wanita itu adalah istri Lin Chong, jadi mereka berkata: “Maaf, saya tidak tahu wanita ini adalah istri pelatih.” Mereka buru-buru menarik Gao Yanei pergi. Pada saat ini, Lu Zhishen juga buru-buru tiba, mengetahui situasinya dan akan mengejar Gao Yanei, tetapi dibujuk oleh Lin Chong. Setelah Gao Yanei melarikan diri, dia masih tidak menyerah dan tidak bisa melupakan istri Lin Chong. Jadi dia bersama dengan Gao Qiu merencanakan untuk menjebak Lin Chong. Gao Qiu mengundang Lin Chong datang ke rumahnya. Karena menunggu lama, Lin Chong menjadi emosi dan membobol Baihu Jietang (Hanzi: 白虎节堂, Pinyin: Báihǔ jié táng) dengan pisau. Lin Chong pun dianggap bersalah, dan dikirim ke penjara. Kelompok Gao Qiu merasa tidak nyaman untuk membunuh Lin Chong di ibukota, jadi mereka mengirim Lin Chong ke Cangzhou (sekarang di Hebei). Lu Zhishen diam-diam melindungi Lin Chong dan membuat keributan, sehingga Lin Chong lolos dari maut. Setelah tiba di Cangzhou (Hanzi: 沧州, Pinyin: Cāngzhōu), Lin Chong ditugaskan untuk menjaga ladang pakan ternak. Gao Qiu mengirim orang ke Cangzhou untuk membakar ladang pakan ternak. Dengan cara ini, diharapkan Lin Chong akan terbunuh, ataupun jika tidak terbunuh akan terkena hukuman mati. Ketika ladang pakan ternak terbakar, Lin Chong mendengar orang kepercayaan Gao Qiu dengan bangga membicarakan rencana pembunuhan Lin Chong. Pada saat ini, Lin Chong tidak bisa lagi menahan marah di hatinya dan membunuh semua musuhnya. Dengan tegas pergi ke Liangshan dan bergabung dengan kelompok pahlawan. Inilah kisah asal usul idiom Tiongkok 逼上梁山 Terima kasih telah membaca, silahkan kunjungi Tionghoa Indonesia untuk artikel-artikel lain yang lebih menarik.

0 notes

Text

Demigods and Semi-devils, Chapter VI (IX)

The man sitting in the centre of the room was, in fact, the emperor of Dali. His name was Duan Zhengming. He was also known by his regnal title, the Baoding Emperor. The kingdom of Dali had been founded during the Five Dynasties period. To be precise, it had been established in the second year of Heavenly Fortune, during the Later Jin Dynasty. In other words, Dali had been a kingdom some twenty-three years before the military revolt which led Zhao Kuangyin to found the Song Dynasty.

The Duans had been people of Wuwei Prefecture. Duan Jianwei, the very first to bear that surname, had served the Meng family under the Nanzhao regime and been given a title: Officer of Peace and Tranquility. Six generations later, his descendant Duan Siping was appointed military commissioner of Tonghai. In the Dingyou Year, Duan Siping founded the Duan Dynasty, and was given the title: Sacred Ancestor and Emperor of Martial Prowess and Learning.

Fourteen generations later and some 150 years later, Duan Zhengming now occupied the throne.

At this time, the Northern Song was nominally ruled by Emperor Zhezong in the capital of Bianliang. But as he was still very young, it was his grandmother - the Grand Empress Dowager Gao - who held true power. It was she who appointed officials to their posts, did away with superfluous regulations, and won the adulation of the people. Under her, the land was at peace. She was the first wise and honest female ruler in China’s history, and had been compared to certain famously benevolent male counterparts.

The kingdom of Dali was located in the wilder southern regions. Its rulers had traditionally been Buddhist, and although they styled themselves emperors, they had always exercised the greatest forbearance and respect when it came to dealing with their Song Dynasty neighbours. This included never raising arms against them. The Baoding Emperor had reigned for eleven years. He espoused three precepts: to defend order, establish peace and secure the blessings of heaven. Under his reign, the borders were quiet and the nation and its people at peace.

Seeing how Mu Wanqing had not knelt to him, and had in fact boldly asked if he was the emperor, the Baoding Emperor could not help but laugh. “I am,” he replied. “Have you enjoyed yourself in Dali City so far?”

“I haven’t seen any of it,” the girl replied. “We came straight here to see you.”

“Well, Yu’er shall bring you about tomorrow and show you some of the sights,” the emperor said, still smiling.

“Great. Will you come with us, then?” At that, everyone present laughed.

The Baoding Emperor looked to his lady, sitting by his side. “My empress, this child wants us to go about the city with her. Shall we?” The woman smiled, but said nothing.

Mu Wanqing looked her up and down. “Are you the empress? You are quite beautiful,” she said.

The emperor burst out laughing. “Yu’er, Miss Mu has such an innocent and honest charm. She amuses me greatly.”

“Why do you call him Yu’er?” Mu Wanqing asked. “He often talks of his uncle - that’s you, right? You know, he’s very afraid that you’ll be angry with him after his recent escapade. But don’t hit him, alright?”

“I was going to sentence him to fifty lashes,” the emperor replied. “But since you’ve asked, I’ll pardon him. Yu’er, you had better thank Miss Mu.”

Duan Yu was very pleased to see how Mu Wanqing had put the emperor in a merry mood. He knew his uncle was an amiable man, and so sketched a deep bow to Mu Wanqing, saying: “Many thanks for speaking up on my behalf.”

Mu Wanqing returned the bow, saying softly: “I’m just relieved to hear that your uncle won’t hit you. You don’t have to thank me.” She turned to face the emperor, adding: “I always thought emperors were rather fearsome and terrifying people, but you’re...you’re really nice!”

The Baoding Emperor had, of course, been praised by his royal father and mother when he was much younger. But apart from that, he had only been treated with respect and fear by his subjects. No one had ever told him that he was “really nice”. Mu Wanqing’s behaviour had all the natural charm of uncut jade or unrefined gold, and nothing of the refined etiquette that he was used to hearing from his courtiers. His affection towards her grew. Turning to his wife, he asked: “What do you have to give her?”

The empress slipped a jade bracelet off her wrist. “Here, this is for you.”

Mu Wanqing took the bracelet and slipped it onto her own wrist. She smiled suddenly. “Thank you,” she said. “Next time, I’ll find something pretty and give that to you.”

The empress smiled back. “Then I thank you in advance.”

Suddenly, a noise was heard several buildings to the west. This was followed by another noise from the pavilion right beside them.

0 notes

Text

The Radiant Emperor audiobooks: a (subjective) comparison

So, because I need to absorb these books through every means possible, I've also listened to the audiobooks in the languages I'm fluent in (Polish, English, French), even though generally I don't listen to audiobooks at all.

Here are my impressions, categorized. I made a separate category for Ouyang's voice not only because he is my fave, but because his voice is described the most specifically of all in the novel and I was really curious to hear the narrators' interpretations of him.

English (narrated by Natalie Naudus)

narration tone: the most captivating narration of the three imo: very vivid, the narrator changes tone frequently and does it well :)

characters' voices: I loved Zhu the most, spot on impression imo. Other characters' voices are top notch, really differentiated and convey a lot of emotion.

Ouyang's voice: very good job with making him sound angry - I usually imagine him speaking in a more "cold, but collected" manner, but the impression of him almost screaming at his officers was great, 10/10, lives in my mind rent free now (along with the stellar delivery of ''why does this untalented bitch play so loudly'')

other remarks: The narrator pronounces the names in accordance with Chinese pronounciation (I guess?), which is very very cool and gives a more authentic vibe. ("Yesen" did throw me out of immersion every time, but that's a me issue.)

overall: most fun audiobook of the three imo

Polish (narrated by Maciej Kowalik)

narration tone: the narrator has a very irritating cadence - "readingonehalfofthesentenceveryfast.....pause.... and then the other half normally", which was probably supposed to build tension, but made the audiobook rather unbearable.

characters' voices: top notch impression of drunk Esen, 10/10. okay in general, though I couldn't bear Ma.

Ouyang's voice: This is the only one of these three audiobooks narrated by a man and it was interesting to hear his interpretation of Ouyang; while not really on the "no voice mutation" side, of course, this version really made the point to make him sound lighter than every other guy but still masculine. very very cool, no notes

other remarks: The audiobook is broken into smaller parts than the book chapters; it's more like one-two scenes from the book per audiobook chapter, and while I think it's an interesting move, I'm not sure if it helps with navigation

overall: it's okay, it's in my language, so that's it I guess. The Ouyang impression is one of its few redeeming qualities.

French (narrated by Sabine Napierala)

narration tone: the most pleasing of the three imo; sometimes the narrator could have used a bit more variation in the tone, though, bc at times I found myself carried away by the sound of her voice and my mind drifting.

characters' voices: GREAT impression of Baoxiang, the best here, no contest; you can really hear the performance Ouyang talks about in SWBTS. This was what I didn't know I needed. Also great Ma and pretty nice impression of Esen. And voices for every character are so different!

Ouyang's voice: here the narrator really nailed the impression that Ma has in HWDTW: raspy yet with something feminine in it. (Maybe it's just the French language is very well suited to that particular kind of voice.) Different from the Polish version, yet still fitting perfectly.

on that note: Ouyang adressing Esen with 2nd person plural (vous) all the time while Esen adresses him with 2nd person singular (tu)... very important to me. the French really went for highlighting the power imbalance between them and I am unwell. (It's a pity, though, that in the '"Come to Bianliang with me" scene the translator didn't make Ouyang use "tu" for maximum shock effect.)

other remarks: There is a musical jingle before every chapter! Fancy :) On the flip side, there isn't a French audiobook for HWDTW yet :( I hope they make it soon bc I can't wait for all the Baoxiang parts honestly

overall: the most relaxing of the three imo (which can be both a blessing and a curse). Definitely my fave but I'm biased on account of going through my ''I miss speaking French on a daily basis'' hours.

#the radiant emperor#the radiant emperor audiobook#świetlisty cesarz#l'empereur radieux#ta która stała się słońcem#celle qui devint le soleil

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

wip tag game

Thank you for tagging me, @astrarche-x and @thestoriesthatweweave

rules: make a new post with the names of all the files in your WIP folder, regardless of how non-descriptive or ridiculous. tag as many people as you have WIPs. people send you an ask with the title that most intrigues them, then post a little snippet or tell them something about it!

I've cheated slightly and restricted the list to Radiant Emperor and Cdrama, and omitted those where I really haven't got anything that is fic that I could quote (fics where the file is paper are also not included!). It's quite long enough a list as it is. As you can see, I am not a person who generally comes up with titles before writing...

Madam Zhang reincarnation

Ouyang fix it with Prince of Radiance therapy

Post brothel fic

Fic Ouyang rebuffs Esen they argue

Esen reads Confucius

Zhao Man fic

Ouyang and WB teens fic

Zhu and Ma are spotted fic

Come to Bianliang fic goes differently snow

Consort Jing and Consort Yue

Five Times Prince Jing

MCS is not Lin Shu

Prince Jing consort fic

WB alternative endings

WB Fan Xianger thoughts

Tagging makes me ridiculously self-conscious so I'm just going to say that this is fun and anyone who hasn't get, maybe go for it? I’m tagging @mispatchedgreens@gatoraid and @nineveh-uk if you haven’t been tagged yet (no pressure if you don’t feel like doing it, obviously), and anyone else among my mutuals/followers who wants to do this!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Foreword 2 (Ma Liping)

The little round table by our open-plan kitchen is always buzzing with activity. It was on this table that Jianfeng propped open his laptop computer and steadily - tik tak, tik tak - tapped out Ten Years a Peasant - Memories of Libeishang to leave for our children.

Jianfeng recounted story after story about life in the village. As my sent-down friends and I followed along, we discovered thoughts that had lain undisturbed and scenarios that had been dormant for decades.

In the late 1960s, we were middle schoolers who had grown up in Shanghai. We were swept up in the feverish winds of the Cultural Revolution and deposited in distant, strange, isolated villages in the mountains. At the time, we didn't expect to encounter a farming civilization that had been passed down through millenia. Looking back on it, we didn't know how valuable that perspective could be.

This realization came long after I left the village and even the country. Since then, I've kept realizing new ways in which that culture contained many facets of our ancient civilization. For example, I was recently reading about the origins of the character "���, again." I was shocked to learn that the oracle bone script and bronzeware script versions were practically illustrations of the fish traps we used in the villages*. We called them "籇(háo)," and there's a photograph in chapter 29. I remember following along curiously as the villagers installed háo in the creek. It was strange to realize that I had literally touched something in the same way as someone from the birth of my civilization! In the Classic of Poetry, from the seventh century BC, they mention 蓑(sūo) and 笠(lì), the traditional cape and hat worn in the rain. While reading that poem I thought of my younger self wearing such things in the spring rain. I was singing a harmony with my ancestors; the barrier between us, a million days' worth of time, was suddenly lifted.

Oracle bone script.

Bronzeware script.

The local dialect had many archaic characters and pronunciations. For example, calling old people "老者, older ones", or going home as "去归, returning." Their strange pronunciations of "sister" and "brother" confounded me at the time. Later, when I was reading Shuowen Jiezi (an ancient Chinese etymological dictionary), I learned that the villagers were using the pronunciations recorded in the Eastern Han dynasty. That sent a chill down my spine. Their illiterate culture contained the ideas of Sunzi Suanjing (The Mathematical Classic of Master Sun), Zengguang Xianwen, and countless folk songs, riddles, and stories. Very few of the villagers had gone to school, but I never felt that they were ignorant or uncivilized. Their stubborn vitality - hardy, honest, frugal, inventive - inspired me. They were amazed by the material conveniences from the city, but their culture and lifestyle shocked this city girl. What Jianfeng has here is a record of his observations while immersed in this ancient culture.

In my mind, everything we were a part of in those villages, including the flashy "signs of the times," is connected to the thread of Chinese civilization. Jianfeng described his experiences working on the reservoir with the whole commune. I myself participated in a multi-county effort to build the Jinggangshan Railroad. Tens of thousands of villagers brought their own tools and supplies to the labor site dozens of miles away from home. Without any compensation we worked on a public project, a re-emergence of the ancient tradition of conscripted labor. Even the "collective production" methods, which may seem misguided now, had their roots in the ideal of "all the world for the public" from Book of Rites.

And yet, unthinkably, as society modernizes and globalization continues its march, these customs that had weathered thousands of years are disappearing before our eyes. They are collapsing under the intoxicating convenience and material wealth of modern times. In the last few years, when we've returned to the villages, we saw a new world: plastic containers replacing a variety of bamboo and ceramic containers; huge concrete edifices replacing traditional brick and lumber; plastic ponchos replacing the tradition suoyi and douli. Even the fragrant rice wine was being replaced with beer. In the rice fields thick with pesticide and chemical fertilizer, fish were few and far between. Even the háo, which had survived since the days of oracle bone script, will have a hard time escaping such a fate. Traditional crafts are on death's door after the introduction of external manufacturing. Folk music, riddles, and stories are withering under the shadow of broadcast media. On the roads, tire tracks cover footprints and engines swallow up the sounds of the village. The rustic culture is changing subtly as luxury is pitted against restraint, laziness against diligence, greed against contentment, recklessness against respect.

Are these swift unbridled changes a blessing or a curse? We can't know. All we know is that to survive, a civilization must remember, and remembering these vanishing forms of life is valuable. Zhang Zeduan painted Along the River During the Qingming Festival in the late Song dynasty. He was able to show us, 800 years later, life in the capital of Bianliang. Maybe Jianfeng's book recording life in the mountain villages of Jiangxi in the 1970s will be able to help others understand the civilization it was a part of.

Beyond the technology sector, our home in Silicon Valley is famous for its reliable sunshine. In the mornings, a square of sunlight splashes onto our dining table as Jianfeng writes. He says that, as he's getting older, the sun warms his back comfortably. Between the tapping of his keyboard, that square sneaks away with time's unceasing footsteps. We leave Ten Years a Peasant for the generations to come, to help them remember today.

Ma Liping, November 2014.

* The meaning "again" derives from these traps' ability to be re-used. The early oracle bone script symbol clearly depicts the shape of the trap and its re-usable mechanism.

Early oracle bone script.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Conviction of Homeland - Xigua JUN [一念山河 - 西瓜JUN」

youtube

一念山河 - 西瓜JUN A Conviction of Homeland - Xigua JUN

文案: 建炎元年,徽钦北虏,易安居士载书十五车,连舻渡淮,又渡江,至建康。 绍兴四年,避乱金华,作《金石录后序》,又作《打马赋》,虽嬉谈文字,却讽朝廷庸碌,��江山易色。 绍兴十三年,勘《金石录》表进庙堂,以悼明诚。二十五年,殒于临安,享年七十有三。 此去二十八年,齐州鸦鼓,历下胡言,但无山河泪,空留一念归。

Background: ’Twas year one of the Jianyan Era of Northern Song, the Emperors Xian and Ren had been taken hostages by the Jin dynasty of the north. Li Qingzhao, also known as the Householder of Yi’an, fled southward with fifteen carriages of books, crossing first the Huai River, then the Yangtze, and finally arrived at Jiankang (modern day Nanjing). ’Twas year four of the Shaoxing Era, she left for Jinhua to avoid conflicts, penned an epilogue to Jin Shi Lu, as well as Da Ma Fu. Though she toyed with words, she mocked the monarch of its corruption and anguished the overturning of her homeland. ’Twas year thirteen of the Shaoxing Era, she revised Jin Shi Lu to be enshrined in their ancestral temple as a memorial to her late husband Zhao Mingcheng. She passed away in Lin’an (modern day Hangzhou) in year twenty-five, aged seventy-three. Thus, twenty-eight years have passed since she left her northern homeland. Drums boomed statewide, nonsense filled the flipped calendar pages, though the landscape cannot weep, she had in her a vain conviction to return.

挽丝浸长江 秋风凉 Hair brushed back dipped into the Yangtze, amid cold autumn winds 与君话朔方 茫茫 With you I spoke of northern tundras, vast and empty as they were 惨惨戚戚山河梦 The sorrowful and woeful dreams of native landscapes 冷冷清清唱 I sang to them with a voice crisp and cool 碧云归鸿望断肠 Into cerulean clouds glided returning geese, as I gazed unto my heartache’s end 故乡 Unto homeland

一念系河山 A conviction belonging to native landscapes 一念化雁返 A conviction returning as soaring geese 宽袖恹凭栏 In loose robes I leaned unaffectionate against railings 夜雨风声烦 Noises of midnight showers and winds displeased me so 枯手剪灯晚 With a weak hand I clipped the candlewick 空梦长安 I dreamt vainly of Chang’an [1] 山河星云暗 Of the landscape stars and clouds dimmed 山河落花残 Of the landscape petals drifted to remains 易安亦难安 Even Yi’an’s anxiousness cannot be eased [2] 笔下存旧念 At the brush tip gathered past memories 确是千万遍 Memories that told countless times 千万遍阳关 Countless times of Yangguan Pass [3]

把绿蚁新尝 Tasting the newly brewed wine 近重阳 Near the time of Chong Yang Festival [4] 一番风雨凉 I stood amid a surge of cold showers and wind 薄裳 Thinly robed 寻寻觅觅凄凄惶 Despairingly how I searched and sought 故国相去长 The long gone native country 梦里山河染墨香 In dreams were landscapes washed with ink 不忘 Unforgotten

一念系河山 A conviction belonging to native landscapes 一念化雁返 A conviction returning as soaring geese 宽袖恹凭栏 In loose robes I leaned unaffectionate against railings 夜雨风声烦 Noises of midnight showers and winds displeased me so 枯手剪灯晚 With a weak hand I clipped the candlewick 空梦长安 I dreamt vainly of Chang’an 山河星云暗 Of the landscape stars and clouds dimmed 山河落花残 Of the landscape petals drifted to remains 易安亦难安 Even Yi’an’s anxiousness cannot be eased 笔下存旧念 At the brush tip gathered past memories 确是千万遍 Memories that told countless times 千万遍阳关 Countless times of Yangguan Pass

一念系河山 A conviction belonging to native landscapes 一念化雁返 A conviction returning as soaring geese 宽袖恹凭栏 In loose robes I leaned unaffectionate against railings 夜雨风声烦 Noises of midnight showers and winds displeased me so 枯手剪灯晚 With a weak hand I clipped the candlewick 空梦长安 I dreamt vainly of Chang’an 山河星云暗 Of the landscape stars and clouds dimmed 山河落花残 Of the landscape petals drifted to remains 易安亦难安 Even Yi’an’s anxiousness cannot be eased 笔下存旧念 At the brush tip gathered past memories 确是千万遍 Memories that told countless times 笔下存旧念 At the brush tip gathered past memories 确是千万遍 Memories that told countless times 千万遍阳关 Countless times of Yangguan Pass

[1] Here, Chang’an, a city that was the capital of many dynasties before the Northern Song Dynasty, alludes to the actual capital of Northern Song, Bianliang (modern day Kaifeng). The lyrics express the poet’s longing for her home country.

[2] Li Qingzhao penned under the pseudonym “Householder of Yi’an”, Yi’an translating to “easily at peace”. This line is meant to express the irony of the uneasiness of someone who supposedly is “easily at peace”.

[3] Yangguan Pass is a fortified mountain pass in Northwestern China. This line alludes to both a work by Li Qingzhao and the poem Seeing Yuan'er off on a Mission to Anxi by Wang Wei. In ancient China, Yangguan Pass was the final stop for travellers departing China and heading out west, and it’s often associated with sad partings. This line expresses Li Qingzhao’s sadness of parting with her homeland.

[4] Chong Yang Festival is a traditional Chinese festival that falls on September 9th of the lunar calendar. It’s customary to climb high mountains and drink chrysanthemum liquor on this day.

0 notes

Text

The Great Wall: Review RSS FEED OF POST WRITTEN BY FOZMEADOWS

Warning: all the spoilers for The Great Wall.

When I first heard about The Great Wall, I rolled my eyes and dismissed it as yet another exploitative tale of Western exceptionalism where the white guy comes in, either insults or co-opts the local culture, saves the day and gets the girl, all while taking a role originally intended for or grossly better suited to a person of colour. It wasn’t until later that I learned the film was directed by Zhang Yimou, filmed on location in Qingdao, China, and featuring a predominantly Chinese cast, with Matt Damon – emphasised in Western marketing to attract a Western audience – starring as one of several leads, in a role that was always intended for a Western actor. The film was released in China at the end of 2016 – and is, in fact, the most expensive film ever shot entirely in China – and was meant to be an international release, designed to appeal to both Chinese and Western audiences, from the outset.

Which left me feeling rather more curious and charitable than I had been; enough so that, today, I went out and saw it. Historically, I’m not an enormous fan of Matt Damon, who always strikes me as having two on-screen modes – All-American Hero and Not-Quite-Character Actor, the former being generally more plausible than the latter at the expense of being less interesting – but I’ve always enjoyed Zhang Yimou’s cinematography, especially his flair for colour and battle sequences. The fact that The Great Wall is ultimately an historical action fantasy film – a genre I am predisposed to love – is also a point in its favour; I’ve watched a great deal of Hollywood trash over the years in service to my SFFnal heart, and even with Damon’s involvement, The Great Wall already started out on better footing than most of it by virtue of Zhang’s involvement.

Even so, I was wary about the execution overall, and so went in expecting something along the lines of a more highly polished but still likely disjointed Chinese equivalent to the abysmal 47 Ronin, an American production that floundered thanks to a combination of studio meddling, language issues with the predominantly Japanese-speaking cast being instructed to deliver their lines in English, last-minute changes and a script that couldn’t decide who was writing it. But of course, 47 Ronin’s biggest offence – aside from constituting a criminal waste of Rinko Kikuchi’s talents – was doing what I initially, falsely assumed The Great Wall was doing: unnecessarily centering a white actor playing a non-white role in an Asian setting whose authenticity was systematically bastardised by the Western producers.

Instead, I found myself watching one of the most enjoyable SFF action films I’ve seen since Pacific Rim. (Which did not waste Rinko Kikuchi.)

The premise: William (Matt Damon) and his companion Tovar (Pedro Pascal) are part of a Western trade mission sent to China to find black powder – gunpowder – for their armies at home. While fleeing Kitan bandits in the mountains, they encounter an unknown monster and, in seeking its origins, are soon taken in by the Nameless Order, an army manning the Great Wall against an expected incursion of the monsters, called Taotie. In charge are General Shao (Hanyu Zhang) and his offsider, Commander Lin Mae (Tian Jing), advised by Strategist Wang (Andy Lau). Every sixty years, the Taotie attack from a nearby mountain, and the next attack is just starting; as such, the Nameless Order and the Great Wall are all that stand between the hoards, controlled by a single Queen, and the nearby capital, Bianliang. While attempting to win Commander Lin’s trust, William makes two alliances: one with Sir Ballard (Willem Dafoe), a Westerner who initially came to China in search of black powder twenty-five years ago; and another with Peng Yong (Lu Han), a young soldier whose life he saves. While Tovar and Ballard are eager to steal the black powder and leave, Commander Lin, General Shao and Strategist Wang are working to counter the evolving strategies of the Taotie: if the Wall is breeched and Bianliang falls, the Taotie will have enough sustenance to overrun the world, a fact which forces William to choose between loyalty to his friends and to a higher cause.

From the outset, I was impressed by the scriptwriting in The Great Wall, which manages the trick of being both deft and playful, fast-paced without any stilted infodumping or obvious plot-holes, aside from a very slight and seemingly genre-requisite degree of handwaving around what the Taotie do when they’re not attacking. The fact that at least half the film is subtitled was another pleasant surprise: of the Chinese characters, both Lin and Wang speak English – their fluency is explained by years of Ballard’s tutelage – and who act as translators for the rest; even so, they still get to deliver plenty of lines in Chinese, and there are numerous scenes where none of the Western characters are present. A clever use is also made of the difference between literal and thematic translations: while the audience sees the literal English translation of the Chinese dialogue in subtitles, there are multiple occasions when, in translating out loud for the benefit of the English-speaking characters, Lin and Wang make subtle adjustments, either politely smoothing over private jokes or tweaking their words for best effect.The scene where Commander Lin’s ability to speak English is revealed made me laugh out loud in a good way: I hadn’t expected the film to be funny, either, but it frequently is, thanks in no small part to the wonderful Pedro Pascal, who plays Tovar so beautifully that he has a tendency to steal every scene he’s in.

Tovar is dry, witty and pragmatic, given to some dark moments, but also loyal, while his establishment as a Spanish character adds another historical dimension to the setting. Aside from calling William amigo, he only gets one real instance of subtitled Spanish dialogue, but the context in which he does this – using it as a private language in Lin’s presence, once her ability to speak English is known – makes for a pleasing gracenote in their collective characterisation. The brief details we’re given of William’s mercenary history, fighting the Danes and Franks and Spaniards, are likewise compelling, a quick acknowledgement of the wider world’s events. It reminded me, in an odd but favourable way, of The 13th Warrior, a film which made the strange decision to cast Antonio Banderas as an Arab protagonist, but whose premise evoked a similar sense of historical intersections not often explored by the action genre.

I also appreciated Tian Jing’s subtle performance as Commander Lin, not only because her leadership of the all-female Crane Corps is objectively awesome – in the opening battle, the women stand on extended platforms beyond the Wall, bungee down on harnesses and spear monsters in the face – but because, refreshingly, not a single person in the film questions either the capabilities or the presence of the female warriors. When General Shao is mortally wounded in battle, it’s Lin he chooses to succeed him, a decision his male Commanders accept absolutely. While there’s a certain inevitable hetero tension between William and Lin, I was pleased beyond measure that this never devolves into forced romance or random kissing: by the film’s end, the Emperor has confirmed Lin as a General, William is on his way back to Europe, and while they’re both enriched by the trust they found in each other, William is not her saviour and Lin is always treated respectfully – both by William, and by the narrative itself.

(Also, The Great Wall passes the Bechdel test, because the female warriors of the Crane Corps talk to each other about something other than men, although they do still, somewhat delightfully, talk shit about William at one point. This is such a low bar to pass that it shouldn’t even merit a mention. And yet.)

Though the action slows a little at the midway point, it remains engaging throughout, while the overall film is structurally solid. As a genre, fantasy action films tend to be overly subject to fridge logic, but the plotting in The Great Wall is consistently… well, consistent. Even small details, like the role of the Kitan raiders, William’s magnet and the arc of Peng Yong’s involvement are consistently shown to be meaningful, lending the film a pleasing all-over symmetry. And visually, it’s spectacular: the Taotie are as convincing as they are terrifying (and boast a refreshingly original monster design), while the real Chinese landscapes are genuinely breathtaking. Zhang Yimou’s trademark use of colour is in full effect with the costuming and direction, lending a visual richness to a concept and setting which, in Western hands, would likely have been rendered in that same flat, drearily gritty sepia palette of greys, browns and blacks that we’ve all come to associate with White Dudes Expressing The Horror Of War, Occasionally Ft. Aliens. Instead of that, we have the Crane Corps resplendent in gorgeous blue lamellar armour, the footsoldiers in black and the archers in red, with other divisions in yellow and purple. Though the ultimate explanation for the Taotie is satisfyingly science fictional rather than magical – which, again, evokes a comparison to another historical SFF film I enjoyed, 2008’s flawed but underrated Outlander – the visual presentation remains wonderfully fantastical.

While I can understand the baseline reluctance of many viewers to engage with a film set in ancient China that nonetheless has Matt Damon as a protagonist – and while I won’t fault anyone who wants to avoid it on those grounds, or just because they dislike Damon himself – the fact that it’s a predominantly Chinese production, and that William’s character isn’t an instance of whitewashing, is very much worth highlighting. While William certainly plays a pivotal role in vanquishing the enemy, the final battle is a cooperative effort, one he achieves on absolute equal terms and through equal participation with Lin. Nor do I want to downplay the significance of Pascal’s Tovar, who represents a three-dimensional, non-stereotyped Latinx character at a point in time when that’s something we badly need more of. Indeed, given the enthusiastic response to Diego Luna’s portrayal of Cassian Andor in Rogue One, particularly the fact that he kept his accent, I feel a great disservice has been done by everyone who’s failed to mention Pascal’s front-and-centre involvement in the project.

I went into The Great Wall expecting to be mildly entertained by an ambitious muddle, and came out feeling engaged, satisfied and happy. As a film, it’s infinitely better than the structural trainwreck that was the recent Assassin’s Creed adaptation, and not just because the latter stars Michael Fassbender, the world’s most smugly punchable man. The Great Wall is colourful, visually spectacular, well-scripted, neatly characterised, engagingly paced and consistently plotted, and while I might’ve wanted to see a little more of General Shao and his offsiders or learn more about the women of the Crane Corps, that wanting is a product of the success of what I did see: the chosen focus didn’t feel narrow by construction, but rather like a glimpse into a wider, more fully-fleshed setting that was carrying on in the background. For Western audiences, William and Tovar are the outsider characters who introduce us to the Chinese setting, but for Chinese audiences, I suspect, the balance of the film feels very different.

The Great Wall is the kind of production I want to see more of: ambitious, coherent, international and fantastical. If we have to sit through the inclusion of Matt Damon this one time to cement the viability of such collaborations, then so be it. With films like La La Land and Fantastic Beasts actively whitewashing their portrayals of America’s Jazz Age, those wanting to support historical diversity could do much worse than see something which represents a seemingly intelligent, respectful collaboration between Western and Chinese storytellers. Maybe the end result won’t be for everyone, but I thoroughly enjoyed myself – and really, what more can you ask?

from shattersnipe: malcontent & rainbows http://ift.tt/2lkPiGZ via IFTTT

5 notes

·

View notes