#Autumn Days (Official Bootleg)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

PSA Regarding Laced/Unlaced

It's come to my attention that there have been recent listings on eBay and other such sites that claim Laced/Unlaced had a "South American re-issue," limited to 1000 copies.

Laced/Unlaced has been issued officially in the following formats, under various titles:

Emilie Autumn "Violin Promo," Messina Records & Rennaisance Management

On A Day..., Traitor Records

Laced/Unlaced Limited Edition Digibook, Trisol Records

Laced/Unlaced Standard Jewelcase, Trisol Records

There was never a South American limited reissue. While the legality of the IronD issues are up in the air, I can say with confidence that this new "reissue" is entirely fake.

If anyone has purchased this bootleg, please send in photos for reference.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cecil Taylor Unit > The Complete, Legendary, Live Return Concert 1973

Official drop: Februrary 15, 2022

Read the liner notes here, or download them from from Scribd.

Cecil Taylor Unit > The Complete, Legendary, Live Return Concert at The Town Hall NYC, November 4, 1973

Oblivion Records OD-8

Read the stories about the album here.

Available on all streaming platforms and Bandcamp

Cecil Taylor: composer, piano Jimmy Lyons: alto saxophone Andrew Cyrille: percussion Sirone: bass

1. Autumn/Parade 88:00 (quartet) 2. Spring of Two Blue-J’s 16:15 Part 1 (solo) 3. Spring of Two Blue-J’s 21:58 Part 2 (quartet)

Composed by Cecil Taylor

.....

Produced by Fred Seibert Recorded live in concert and mixed by Fred Seibert Assisted by Nick Moy The Town Hall 123 West 43rd Street New York, New York

Track 1: Mixed, Summer 2021 Tracks 2 & 3: Mixed, Spring 1974, assisted by Jeff Ader, Alan Goodman, David Laura and Tony May, Spring 1974 Digital transfers from the original analog 4-track and stereo recordings by Sonicraft, Red Bank, NJ Promotional CD Mastering: Tom Nunes, Atomic Disc, Salem, OR

Cover photography ©David Spitzer at Columbia University, 1977 Graphics by The Oblivionettes Publicity: Lydia Liebman Promotions

Essay by Alan Goodman

Special Thanks to Mark Seiden

Producer’s note: This streaming release is the world premiere of “Autumn/Parade,” mixed in July 2021 for the first time since its recording. This drop is the first release of the complete concert from November 4, 1973.

The original LP of “Spring of Two Blue-J’s” was limited to 2000 vinyl pressings in 1974 for Unit Core Records, owned by Cecil Taylor. The only other legitimate release is by Oblivion Records in 2021. All others on vinyl, CD, or any other format are unauthorized bootlegs.

The two part "Spring of Two Blue J's" (Oblivion Records OD-7) is exclusively on all digital streaming platforms.

.....

We knew then it was going to be an event.

By Alan Goodman

We knew then it was going to be an event. That’s my first memory, nearly 50 years later, of Cecil Taylor’s “return” concert at The Town Hall in New York on November 4, 1973.

Cecil had as much claim as anyone to be a star in that era, in that city, but instead had split to spend the early part of the 1970s teaching composition at the University of Wisconsin and Antioch College, where he also devoted time each day to his own composing. A couple of years had passed since his last public solo performance in New York –the epicenter of new music, avant-garde, free jazz, whatever you want to call it if you need to call it anything– and listeners were eager to hear what he was going to reveal, especially with a quartet.

As for LP evidence of his music’s evolution, the most recent touchstone was “Indent,” a solo piano performance at Antioch released just six months before the concert at The Town Hall on Cecil’s label Unit Core, but it was not widely heard until it was released years later by Arista Freedom. In fact, since his groundbreaking LPs on Blue Note in the mid 1960s, Cecil’s recorded output was relegated to mostly small, obscure European labels. The result of all that largely private exploration and discovery would at last be on display by Cecil and his longtime collaborators, alto saxophonist Jimmy Lyons, percussionist Andrew Cyrille, and newcomer Sirone on bass.

The album that documented part of the concert, “Spring Of Two Blue J’s,” was produced and mixed by my friends and me. It received high praise. In his book about the New York music scene in the 1970s, “Love Goes to Buildings On Fire,” Critic Will Hermes called it one of music’s two epiphanies that year (the other being the Dave Holland release, “Conference of the Birds.”)

Longtime Village Voice jazz writer Gary Giddins, who at the time had not yet begun his column, recalls today that Cecil’s solo on the first side was his most impressive to date, and that the quartet movement “climaxed his long alliance with Lyons and Cyrille and introduced bassist Sirone.” Of all Cecil’s discoveries in his musical journey leading to “Blue J’s,” that record’s breakthroughs were, Giddins says, the most revelatory and satisfying, and it “announced Cecil Taylor’s permanent reestablishment in the music world, an end to his marginalization, and the evidence of a maturity that allayed any doubts that he or anyone else may have harbored during that self-imposed exile in academia.” In two Voice wrap-ups in 1974, he called it his favorite album of the year.

Given our involvement in the project –college students who had never recorded or mixed an album before, outside of a few, small personal dates– the praise was enormously gratifying.

What almost no one knew was that “Spring of Two Blue J’s” documented just one part of the concert; the shorter, second set. Now, at last, we can present the rest of that night’s story.

“The Complete, Legendary Return Concert” includes the first portion of the concert that has been sitting in a tape box all this time. It includes the compositions “Autumn/Parade,” and it’s a feast. Listening to it for the first time in 50 years alongside “Blue J’s,” it’s clear that this concert was more than a triumphant return. It was also the concert that established how Cecil would be performing for the rest of his life, and how his hunger to explore the limits of human artistry would make each concert as demanding on the listener as on the performers.

Why “Blue-J’s” was released at the time, and not the concert’s first set, was strictly a consequence of recording technology in 1973. “Autumn/Parade” is 88 minutes long, and Cecil is playing almost continuously throughout. On its own, it would have necessitated a double-album set, which was considered to be not commercially viable (The single disk “Blue-J’s” retailed for $6.50). Plus, each side would need to be faded down and faded up on the next side, a solution that is never artistically satisfying, though it was the solution chosen for Arista’s Cecil releases.

“Blue J’s” had a more natural place to break, with Cecil’s piano solo on Side One and the ensemble joining him on Side Two, so that became the record. Thanks to the opportunity today for digital releases, “Autumn/Parade” can be presented as it was heard that night, a marathon of brilliant invention, cascading emotions, and almost unimaginable synchronicity among the musicians pouring everything they had into the performance.

******************

How we became involved in the concert is a story in itself.

Fred Seibert was a senior at Columbia University, I was a year behind him, and the school’s radio station, WKCR, was our second home. Still known for championing primarily jazz and classical music, as a non-profit educational broadcaster we were free from the obligation to be commercially successful. That gave comfort in bending the boundaries (and listeners ears) in both genres to a merry band of counterculture misfits from a spectrum of ethnicities and races. There was another jazz station headquartered just a few blocks up from us on Broadway. They played the hits and the big names. At a time when the downtown loft jazz scene was flourishing and the avant-garde in the U.S. and Europe was attaining new levels of recognition, we liked to play the albums that other station ignored. It was more than a hobby, or an extracurricular activity. We approached exposing new music to listeners like we were on a mission. Being young and in New York, the WKCR playlist (well, in fact, there was no playlist) was our call for representation, inclusion, and acceptance.

If you couldn’t handle everything we played, so be it. At least we gave you a place to sample it, 24 hours a day (not counting news programming and music from other cultures that filled weekend hours). Some of the staff members showed up for their shifts and went home. Others appeared to never leave.

One day, into that environment, walked a fellow named David Laura, who had in tow inventor and jazz guitarist Emmett Chapman. Emmett had come up with an instrument called the Chapman Stick –a 10-stringed fretted board like a wide guitar neck that was tapped two-handed, allowing one performer to play dense polyphonic chords, or lead and bass simultaneously. Emmett’s innovation is a story for another time, but Laura’s visit to the station introduced him to some of the mole-like creatures who would curl up behind the piano for a snooze, or burrow into a news booth with a stack of library books and a pitcher of coffee from the Chock Full ‘O Nuts across the street, desperately trying to finish a term paper in one night.

Laura took note of Fred, an aspiring record producer at the time and one of the most persuasive individuals you will meet in your life. Fred had launched his own label, Oblivion Records, with an eclectic mix of blues and fusion. Oblivion’s catalog was not going to make anyone wealthy. One of his partners used cartons of records as a coffee table.

Several months later, Laura was back with a proposal. He was going to bring the Cecil Taylor Unit to The Town Hall, and he wanted Fred to record it. Fred had engineered some things at the station –live performances over the

radio– but knew only a little about mic placement and the like, but to hear him with Laura, he was the perfect man for the job.

To prepare for the date, Fred approached a former WKCR colleague who was known to have a four-channel recorder and a collection of studio quality Neumann microphones that he had neither purchased nor rented, and if a crime was committed in obtaining them, the statute of limitations has long run out. So along with Nick Moy, Fred’s roommate and another WKCR stalwart, Fred lugged the

stolen equipment in a cab to West 43rd Street and set up to record one of the most extraordinary music performances we would ever hear.

We couldn’t help reflecting that his previous albums receiving any significant distribution were released when we were high schoolers. The concert at The Town Hall was an opportunity to do more than be spectators and enthusiasts of the history of jazz. This concert gave us a chance to participate in it.

****************

Jazz is, above all, the music of freedom. It makes room for personal expression in

improvisation, a rebellion against formal composition. Jazz champions a soloist’s style, and allows embellishment over another musician’s composition by shaping, caressing, or attacking with sound. It embraces dissonance, reveling in the tension it creates and the satisfaction of its resolution.

And it swings. Swinging is the ultimate revolt as it is the revolt against time. Other factors play into it, such as an emphasis on the “weaker” notes that pushes the performance forward and causes your hips to sway, but it’s that battle between where the beat should be and where the musician puts it that forces your feet to move in a joyous attempt to arbitrate between them, a celebration of an individual’s interpretation of time rather than the way math divides it, that gives jazz its innate jazziness. That small act of freeing eighth notes from their evenness is nothing short of a musical insurrection.

From the start, Cecil Taylor was working to achieve freedom through his music. He found his over a long span.

Most summaries of Cecil’s career do an incomplete job of representing how his music evolved, focusing mostly on his complex and marathon-like performances that required enormous concentration and steered clear of most signifiers that identify jazz. In fact, there was a progression, and the Town Hall concert announced his final phase of development.

As a student at the New England Conservatory in Boston, he studied composition and was influenced by the European art music tradition, but in general his studies left him frustrated by a lack of appreciation for black music and African American cultural treasures. His personal listening brought him to composers and performers in both classical and jazz traditions that were on the “outside” of typical expression – artists who sounded like no one else and were exploring a more personal path.

From his earliest recordings, Cecil declared his independence by reinterpreting composers who were already on the fringes, or playing funhouse mirror reflections of traditional standards. For instance, he was deeply immersed in the off-kilter world of Thelonious Monk’s compositions but also in Monk’s decisive choice to hit the notes that didn’t quite fit. Cecil took it even one step farther. His version of “Bemsha Swing” from the mid 1950s is inside and outside the song. There’s this thing we know that is “Bemsha Swing,” itself a composition that was in no way typical. Cecil is playing it, but he’s also playing with it.

His version of “You’d Be So Nice To Come Home To” seems more a reflection on the title and any emotion that might be triggered by “coming home” than it is a version of the Cole Porter standard. You’d be so nice to come home to, even though that includes feelings of tension, anxiety, fear and defiant joy. Porter had no idea what he had scribbled down until Cecil Taylor got a hold of it.

From 1956, both those recordings share the album that includes “Rick Kick Shaw,” a tour de force where you can hear some of the influence pianist Lennie Tristano had on Cecil. He uses the tune to work through phrases and themes until he’s worked them out, or worn them out. In both originals and interpretations, Cecil and his band are playing with unmistakable jazz feel.

Likewise, on “Hard Driving Jazz” (1959), later retitled “Stereo Drive” and “Coltrane Time,” Cecil is providing an unfamiliar bed for the other soloists, but he is nevertheless laying down a surface that references the songs, obeys the conventions of typical comping, and unquestionably swings.

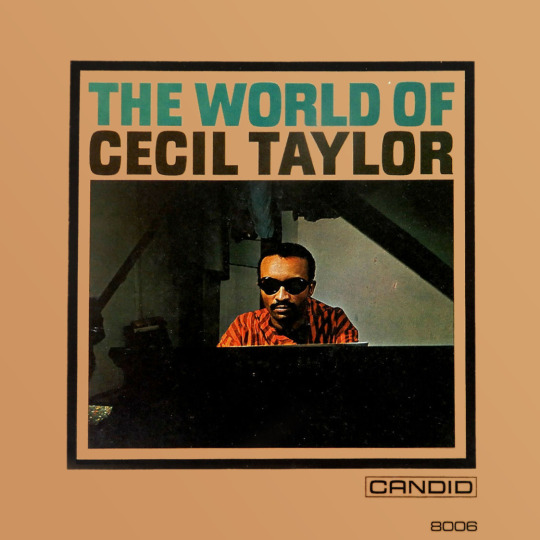

On the recordings he made for Candid in 1960 and 1961, Cecil is still playing jazz even though on many of the compositions you’d be hard pressed to find a chord progression. The music is syncopated, though liberated from harmonic presumptions. By the time we get to the brilliant Blue Note records “Unit Structures” and “Conquistador!” in 1966, Cecil has virtually abandoned rhythmic signposts in his playing, though the songs have heads and the backing musicians adhere to expectations. His fellow musicians match him with their passion, but still provide an access ramp for mainstream jazz listeners. Passages of intense fury give way to softer segments as well as to defined statements composed and performed by his sidemen.

The concert that netted “Spring of Two Blue J’s” and now, “Autumn/Parade,” is where you hear Cecil and his entire band having finally broken through the bonds of time. As freeing as it was to swing, Cecil has abandoned even that boundary. Eliminating swing was the final freedom, along with the idea that a “piano

player” should sit at the piano and not get up and dance for an hour if that was what his performance compelled him to do (there was no dance at The Town Hall, but dance was coming soon to Cecil Taylor’s live performances).

And I would argue time ceases to exist for Cecil, not just in the way a song is metered but also in the arc of a performance. Cracking the shackles of time freed him from that thing Captain Beefheart called “mama heartbeat,” the orderliness of a composition that made it… regular. Typical. Hypnotic. If we are no longer being hypnotized hearing that heartbeat, we can instead experience this music like blood running through the veins, which knows no time and is the essence of life.

Guaranteed – at the end of “Autumn/Parade,” concert-goers that night in 1973 looked at their watches and said, “What? That was 88 minutes??? No way!”

You lose all sense of time caught up in the way these musicians fuel each other, at times give way to one another, build and recede. What happens at about 3:50 when Cecil’s playing is suddenly more brittle and in a flash, Jimmy is matching him? What sets off the flurry of total engagement that begins to build about one minute later and lasts about 15 minutes, until an almost imperceptible shift to a more sparse dialogue between Cecil and Sirone? What signals Jimmy’s reentry at 25:00, or the reduction and rebirth at around 40:00 minutes when it’s just Cecil? What was the impetus for Jimmy Lyons’ restatement of his opening phrase at 49 minutes, resetting the stage for the next crescendo? How had they prepared, or in what manner did he point to transitions? We can’t know how this was composed, rehearsed, molded and revised. We can only experience it as participants in the concert experience.

****************

Hours of searching have produced no evidence the concert was anticipated, covered in the press, or reviewed. That weekend in the New York Times, it made the “Jazz/Rock/Folk/Pop/” listings and in Sunday’s Arts section, a one-column inch ad appeared at the very bottom of the page with the word “TONIGHT” plastered diagonally across it in letters so large they obscured the name of the artist appearing. No reviews have turned up. But after “Blue J’s” appeared, sentiment began to build that Cecil had broken through something significant and lasting, setting him apart from any faction, category, or record bin into which he had been filed.

Critic Giddins says that what Cecil accomplished was “something heroic, a new language largely bounded by the tempered scale that evaded its clichés and formulae.” In his view, “Cecil had developed his own patterns of sound, melody, and rhythm, as well as a distinct touch involving extreme dynamics and extraordinary digital precision.”

Recently, given an early listen to“Autumn/Parade,” Giddins described it as an “extraordinary gift,” likely to be among the most significant discoveries that will fill out Cecil’s discography as more tapes of unreleased concerts and sessions come to light. He singled out “the disarming beginning” and “the lovely moment as Jimmy’s saxophone makes its first appearance and Cecil’s piano cradles it in a perfectly complementary chord,” as well as Cecil’s “virtuosic solos no one else could conceive.” He praised as well Cecil’s “epic thunderstorm, which dominated the final half hour of the piece, finishing on a peak of delighted triumph.”

Another jazz fan who delighted in Cecil’s work 50 years ago was also given early access to “Autumn/Parade.” She wasn’t a survivor. “I can’t anymore,” she told me. A reaction I’d like to think Cecil would respect, as this is supposed to be a dialogue, a pact, between performer and listener.

Or maybe she needs to try again. After seven listenings, it is still providing me surprises and encouraging the next listen. There is nothing about it that says its vintage was half a century ago. It is about now because it touches your life, in a vibrant, visceral, life-affirming sound experience.

Enjoy the “extraordinary gift” of “Autumn/Parade.” And rest in peace, Cecil Taylor.

Alan Goodman is a writer. He was a DJ and engineer at WKCR, where he also produced news and cultural programming. He is a former journalist and producer who wrote for newspapers, magazines, radio and television. He wrote two books for Simon & Schuster and a comic book for Virgin Comics, and has written for Mosaic Records since 1984.

(This entire essay, plus assorted visual emphemera of The Return Concert, is included and downloadable in the PDF booklet at the top of this post. Enjoy.)

LINER NOTES BOOKLET & DESIGN ©2022, OBLIVION RECORDS 2021, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

#Cecil Taylor#Cecil Taylor Unit#Andrew Cyrille#Jimmy Lyons#Sirone#jazz#avant-garde#avant-garde jazz#live#concert#OD-8#OD8#digital#Spring of Two Blue-J's#1973#2022#piano#composer#free jazz#Return Concert#The Return Concert

0 notes

Text

Remember Me? - Extract from Dream Brother Part 1 of 2

Jeff Buckley drowned three years ago. He’d seemed on the brink of a brilliant rock ‘n’ roll future. Yet he had never shaken off his obsession, part anger, part yearning, with the father he had barely known - Tim Buckley, legendary singer-songwriter. David Browne on their lives and destiny

Friday 15 December 2000 19.17 EST

Although dusk was in sight, the moist, breezy Memphis air still felt mosquito-muggy inside and outside. It was May 1997 and Jeff Buckley, who had turned 30 about six months earlier, emerged from his bedroom in black jeans, ankle-high black boots, and a white T-shirt with long black sleeves and “Altamont” (in honour of the Rolling Stones’ anarchic, death-shrouded 1969 concert) inscribed on it. Though officially out of his 20s, he remained a rock'n'roll kid at heart. As he and his tour manager Gene Bowen stood outside on the front porch, Jeff said he was heading out for a while. Generally Bowen would accompany Jeff on expeditions while on tour, but tonight Bowen needed space. Some mattresses would be delivered shortly, and the last thing he needed was Jeff bouncing around the house when they arrived.

So, when Jeff told Bowen he would be leaving with Keith Foti, Bowen was mostly relieved. Foti was even more of a character than Jeff was. A fledgling songwriter and musician and a full-time haircutter in New York City, Foti had accompanied Bowen from New York to Memphis in a rented van, the band’s gear and instruments crammed in the back. Stocky and wide-faced, with spiky, blue-dyed hair, Foti, who was 23, could have been the star of a Saturday morning cartoon show about a punk rock band.

Jeff told Bowen that he and Foti had decided to drive to the rehearsal space the band would be using during the upcoming weeks. Bowen told them to be back at the house by nine to greet the band. Jeff said fine, and he and Foti ambled down the gravel driveway to the van parked in front of the house.

Suddenly it dawned on Bowen: did Jeff and Foti know where the rehearsal space was? For non-natives, Memphis’s layout can be confusing; it wouldn’t be hard to get lost or suddenly find one’s self in a dicey part of town. Bowen bolted through the front door, but the van was already gone. Oh, well, he thought, they’ll find the building. After all, they had been there just yesterday.

Cruising around Memphis in their bright yellow Ryder van, past weathered shacks, barbecue joints, pawnshops and strip malls, Jeff and Foti made for an unusual sight. Foti was in the driver’s seat, which was for the best; Jeff was an erratic driver. They cranked one of Foti’s mix tapes, and the two of them sang along to the Beatles’ I Am The Walrus, John Lennon’s Imagine and Jane’s Addiction’s Three Days. Foti and Jeff both loved Jane’s Addiction and its shamanesque, hard-living singer, Perry Farrell. It took Jeff back to the days in the late 80s when he was living and starving in Los Angeles, trying to make a name for himself.

It wasn’t Jeff’s fault that he shared some vocal and physical characteristics with his father and fellow musician, Tim Buckley. Both men had the same sorrowful glances, thick eyebrows and delicate, waifish airs that made women of all ages want to comfort and nurture them. It wasn’t Jeff’s fault, either, that he inherited Tim’s vocal range, five-and-a-half octaves that let Tim’s voice spiral from a soft caress into bouts of rapturous, orgasmic sensuality. In the 60s, Tim wrote and sang melodies that blended folk, jazz, art song and R&B; he had a large cult following himself, and some of those songs had been recorded by the likes of Linda Ronstadt and Blood, Sweat & Tears.

When Jeff had begun writing his own music, he, too, moved in unconventional ways, crafting rhapsodies that changed time signatures and leapt from folkish delicacy to full-throttle metal roar. None of this, he insisted, came from his father’s influence. His biggest rock influence and favourite band was, he said, Led Zeppelin. To his friends, Jeff talked about his bootleg of Physical Graffiti out-takes with more affection and fannish enthusiasm than he ever did about the nine albums his father had recorded during the 60s and 70s.

Tonight, for once, Tim’s ghost was not lurking in the rearview mirror. If anything, Jeff seemed at peace with his father’s memory for perhaps the first time in his life. Whenever Jeff had mentioned Tim in the past, it was with flashes of irritation or resignation. He sounded as if he were discussing a far-off celebrity, not a father or even a family member. In a way, Tim was barely either: he and his first wife, Mary Guibert, had separated before Jeff was born, and Jeff had been raised to view Tim’s life and music warily. But in the past few months, Jeff seemed to have begun to understand his father’s music and, more importantly, his motivations.

Jeff’s years in Los Angeles hadn’t been fruitful, but when he moved to New York in the autumn of 1991, a buzz began building around the skinny, charismatic kid with the big-as-a-cathedral voice and the eclectic repertoire. Many record companies came calling, and he eventually, hesitatingly, put his name on a contract with one of them, Columbia. After an initial EP, an album, Grace, finally appeared in 1994. A brilliant sprawl of a work, the album traversed the musical map, daring listeners to find the common ground that linked its choral pieces, Zeppelin-dipped rock and amorous cabaret. Certainly one of the links was Jeff’s voice, an intense and seemingly freewheeling instrument that wasn’t afraid to glide from operatic highs and overpowering shrieks to a conversational intimacy.

Beyond being simply one of the most moving albums of the 90s, Grace branded Jeff as an actual, hype-be-damned talent for the age. The record business was always eager to promote newcomers in such a manner, but here was someone with both a sense of musical history and seemingly limitless potential. Like Bob Dylan and Van Morrison before him, he appeared to be on the road to a long and commanding career in which even a creative misstep or two would be worth poring over. Comparisons with Tim were inevitable, and a disturbing number of fortysomethings had materialised at Jeff’s concerts to ask him about his father. But, much to Jeff’s relief, the comparisons had begun to diminish with each passing month.

Grace hadn’t been the smash hit Columbia would have liked, but worldwide it had sold nearly 750,000 copies, and it was talked up by everyone from Paul McCartney and U2 to Zeppelin’s Robert Plant and Jimmy Page. Fans in Britain, Australia and France adored him even more passionately than those in America. To his managers and record company, Jeff was a shining star, a gateway to prestige, money and credibility. A very great deal was riding on the songs he was testing out on the four-track recorder in the living room of his house in Memphis. Jeff didn’t like to think about those pressures, which is partly why he moved 1,000 miles away from New York. Here, he could think, write, create.

The drive from Jeff’s house to Young Avenue, where the rehearsal room was located, should have taken 10 minutes down a few tree-lined streets. But something was wrong. Before Jeff and Foti knew it, nearly an hour had passed and there was still no sign of the two-storey red-brick building. They found themselves circling around a variety of neighbourhoods, past underpasses for Interstate 240 and pawnshops. To Foti, everything began to look the same.

Jeff had an idea. “Why don’t we go down to the river?” he said. It sounded good to Foti, who had brought along his guitar and felt like practising a song he was writing. Having a talented, well-regarded rock star as an audience wouldn’t be so bad, either.

The Wolf River did not look particularly wolfish; it barely had the feel of a river. The city government had passed an ordinance banning swimming, but no signs indicated this restriction. According to locals, there didn’t have to be, since everyone in Memphis knew it was far from an ideal swimming hole. The first six inches of water could be warm and innocuous-looking, but thanks to the intersection with the Mississippi the undercurrents were deceptive. All day long and into the early hours of the morning, 200ft-long barges carrying goods from the local granaries and a cement factory hauled their cargo up and down the Wolf. With their churning motors, the tugboats that pulled the barges were even fiercer and had been known to create strong wakes. Local coastguard employees had once witnessed a 16ft flat-bottom boat being sucked under the water in the wake of a tug. Memphis lore had it that at least one person a year drowned in the Wolf.

Even if Jeff had heard these stories, he either didn’t care or disregarded them. Hopping over a 3ft-high brick wall, Jeff and Foti strode across a cement promenade strewn with picnic tables. Then Jeff hiked his black combat boots on to the bottom rung on the steel rail that ran alongside the promenade and jumped over. Foti, gripping his guitar, followed, and they found themselves barrelling down a steep slope, swishing through knee-high brush, ivy and weeds.

On the way down, Jeff shed his coat - just dropped it in the brush. “You’re not gonna leave it here, are you?” Foti asked, stopping quickly to pick it up. Jeff didn’t seem to be listening. Carrying Foti’s boom box, he continued down to the riverbank. The shore was littered with rocks, soda cans and shattered glass bottles, and it quickly sloped into the water just inches away. As gentle waves lapped on to the shoreline, Jeff set Foti’s boom box on one of the many jagged slate rocks on the bank, just an inch or so above the water. “Hey, man, don’t put my radio there,” Foti told him. “I don’t want it going in the water. It’s my only unit of sound.” Jeff didn’t seem to pay particular attention to that request, either.

By now, just after 9pm, Foti had strapped on his guitar and started practising his song. Looking right at Foti, Jeff took a step or two away, his back to the river. Before Foti knew it, Jeff was knee-high in the water. “What are you doin’, man?” Foti said. Within moments, Jeff’s entire body eased into the water, and he began doing a backstroke.

At first, Foti wasn’t too concerned: Jeff was still directly offshore, just a few feet away. He and Foti began musing about life and music as Jeff backstroked around in circles. “You know, the first one’s fun, man - it’s that second one … ” Jeff said, his voice trailing off as he continued to backstroke in the water.

With each stroke, Jeff inched more and more out into the river. Foti noticed and said, “Come in, you’re gettin’ too far out.” Instead, Jeff began singing Led Zeppelin’s Whole Lotta Love. “He was just on his own at that point,” Foti says. “He didn’t really observe my concerns.” Jeff had an impetuous, spur-of-the-moment streak. Many of his friends considered it one of his most endearing qualities; others worried that it bordered on recklessness. Like his father, he liked to follow his muse, to leap into projects passionately and spontaneously, even if they weren’t fashionable or appropriate. Take that night in 1975. Tim was on his way home from a gruelling tour. His record sales were in freefall, but lately he had tried to cut back on his drinking and drugging, and was attempting to get his music and even a potential acting career on track. On the way home from the last stop on his tour, he stopped by the home of a friend, who offered up a few drugs. What was wrong with a little pick-me-up after some exhausting road work? No one knew if Tim realised exactly what he had snorted that late afternoon, but it ultimately didn’t matter; he died that night of an overdose at the age of 28.

Although Jeff had experimented with drugs, he steered clear to avoid his father’s fate, both physically and artistically; he had learned from Tim’s mistakes in the matters of artistic integrity and handling the music business. Onstage, Jeff would often make cracks about dead rock stars, pretending to shoot up or breaking into spot-on mimicry of anyone from Jim Morrison to Elvis Presley. Once this new album was completed, he was planning to dig deeper into his family heritage and unearth the truth behind the seemingly ongoing series of tragedies that haunted his lineage.

Tonight, as he backstroked in the water, Jeff appeared to feel freer than he had in a while. The mere fact that he was in water was a sign of change. Although he had grown up near the beaches of Southern California, Jeff was never a beachcomber.

It was now close to 9.15pm, and Jeff had been in the river nearly 15 minutes. His boots and trousers must gradually have become more sodden and heavy. He began swimming further toward the centre of the river, circling around before drifting to the left of Foti. Then he began swimming straight across to the other side, or so it appeared to Foti. Directly across from them, on the opposite bank, was a dirt road that ran right up from the river. It looked so close - maybe Jeff felt he could reach it and take a quick stroll.

The tugboat came first, moments later. “Jeff, man, there’s a boat coming,” Foti said. “Get out of the fucking water.” The boat was heading in their direction, up from Beale Street. Jeff seemed to take notice of it and made sure to be clear of it as it passed. The next time Foti looked over, he still saw Jeff’s head bobbing in the water.

Not more than a minute had passed when Foti spied another boat approaching. This one was bigger - a barge, perhaps 100ft long. Foti grew more concerned and started yelling louder for Jeff to come back. Once again, Jeff swam out of its path, and Foti breathed another sigh of relief. In the increasing darkness, the speck that was Jeff’s head was just barely visible.

Soon, the water grew choppy, the waves lapping a little more firmly against the riverbank. Foti grew worried about his boom box. The last thing he wanted was to see it waterlogged and unusable. Taking his eye off Jeff for a moment, he stepped over to where Jeff had set the stereo down on a rock and moved it back about five feet, out of reach of the waves. Foti turned back around. There was no longer a head in the water. There was nothing - just stillness, a few rippling aftershock waves, and the marina in the distance. Foti began to scream out Jeff’s name. There was no answer. He yelled more. He continued screaming for nearly 10 minutes.

On the other side of the river, Gordon Archibald, a 59-year-old employee of the marina, was walking near the moored boats with a friend when he heard a single shout of “help”. Concerned, he looked out on to the water. But he saw nothing, nor heard anything more.

The folk singer Tim Buckley, who was to become Jeff’s father, married Mary Guibert in 1965.

It was spring 1966, Mary Guibert was three months pregnant, 18 years old, and Tim was out of town. Even before Tim left for New York, his wife suspected he was spending time with other women. “By no stretch of the imagination was this a marriage made in heaven,” she says. “He hadn’t been faithful to me for very long. And I thought that was perfectly acceptable because, after all, he was so wonderful, and I was so nobody.”

Mary says she told Tim about the pregnancy before he left for New York, but that he told her he had to leave town and that she should move back in with her family in Orange County, near LA, get a job, save money, and “maybe get an abortion or whatever you want to do”, she recalls him saying. Even then, Tim made no mention of another woman. “I just had no idea,” Mary says. “A lot of denial going on. Tons of denial on both sides, because he wouldn’t bring himself, to the very end, to say, 'You know, I really don’t love you very much’.” She sent Tim letters to various addresses in New York; his replies came fitfully and were pointedly vague. Finally, a mutual friend gave her the news: Tim was in New York with a new girlfriend, and would be back in Los Angeles shortly.

Lee Underwood, guitarist in Buckley’s band and a great friend, recalls the situation being a topic of discussion while he and Tim were in New York that summer. Given the choice of returning to Mary and Orange County or following what Underwood calls “his destined natural way”, Tim “decided to be true to himself and his music, fully aware that he would be accepting a lifetime burden of guilt. Tim left, not because he didn’t care about his soon-to-be-born child but because his musical life was just beginning; in addition, he couldn’t stand Mary. He did not abandon Jeff; he abandoned Mary.”

Finally, some action had to be taken. Tim came to meet Mary at a coffee shop near her home. What exactly happened remains unclear. Tim never talked to his friends about it, while Anna Guibert, Mary’s mother, recalls Tim giving Mary an ultimatum: divorce or abortion. According to Mary, she asked Tim what they should do about the marriage and pregnancy, and he replied, “You do whatever you have to do, baby”, and hung his head.

Afterwards, Mary, who was by now many months pregnant, walked home, told her mother the news and cried. As Anna Guibert remembers, “I said, 'That’s the best thing, honey. If he doesn’t want you, be free.’ She was crazy about Tim. But he wanted his career. There was no place for a baby in his life."Mary, however, did want her baby.

He was born on Thursday, November 17, 1966, at 10.49pm, after 21 hours of labour. The issue of identity loomed even before the child left the hospital. Mary named her son Jeffrey Scott - "Jeffrey” after her last high-school boyfriend before Tim (“my last pure boy-girl relationship, my last pure moment”) and “Scott” in honour of John Scott Jr, a neighbour and close friend of the Guiberts who died in an accident at the age of 17. Yet because Mary preferred Scott, the child was instantly called Scotty by his family. Tim was not available for consultation, since no one knew his whereabouts.

At school, Scotty was the eternal clown, making jokes, craving attention and being more interested in music (including cello lessons provided by the school) than grades. His second-floor bedroom became a rock enclave, his most valuable possessions being a Hemispheres picture disc by the prog-rock band Rush and all four of Kiss’s solo albums.

He had a guitar given to him by his grandmother, and although he hadn’t learned to master it, he would sit and cradle it, “like Linus’s blanket”, according to Willie Osborn, his childhood friend. Although Jeff had taken his father’s name, his music tastes reflected none of Tim’s influence. He was just eight years old when Tim died; they had had their only proper encounter just months before.

The meeting between Tim and Jeff Buckley, April 1975.

Mary Guibert was flipping through a local newspaper when she saw a listing for Tim Buckley’s upcoming show. It was, she says, “an epiphany”. It had been six years since she and her first husband had seen each other, and nearly as long since they had spoken. Mary and Jeff took the hour-long drive to Huntington Beach, an oceanside town 10 miles southwest of Orange County, and arrived at the Golden Bear just before Tim walked on-stage. They took a seat on a bench in the second row.

Jeff seemed enraptured, bouncing in his seat to the rhythms of Tim’s 12-string guitar and rock band. “Scotty was in love,” Mary says. “He was immediately entranced. His little eyes were just dancing in his head.” To Mary, Tim was still a dynamic performer, bouncing on his heels with his eyes shut, but she also felt he looked careworn for someone still in his 20s.

At the end of the set, no sooner had Mary asked her son if he wanted to meet his father than the kid was out of his seat and scurrying in the direction of the backstage area. As they entered the cramped dressing room, Jeff clutched his mother’s long skirt. It seemed a foreign and frightening world to him, until he heard someone shout out, “Jeff!” Although no one had called him that before in his life - he was still “Scotty” to everyone - Jeff ran across the room to a table where Tim was resting after the show.

Tim hoisted his son on to his knees and began rocking him back and forth with a smile as Jeff gave his father a crash course on his life, rattling off his age, the name of his dog, his teachers, his half-brother and other vital statistics. “I sat on his knees for 15 minutes,” Jeff wrote later. “He was hot and sweaty. I kept on feeling his legs. 'Wow, you need an iceberg to cool you off!’ I was very embarrassing - doing my George Carlin impression for him for no reason. Very embarrassing. He smiled the whole time. Me too.”

Tim’s drummer, Buddy Helm, recalls. “It was a very personal moment. The kid seemed very genuine, totally in love with his dad. It was like wanting to connect. He didn’t know anything personally about Tim but was there ready to do it.” The same seemed to be true of Tim; after years of distance from his son, he seemed to feel it was time to re-cement whatever bond existed between them.

Shortly after, before the second set began, Judy, Tim’s new partner, asked Mary if it would be acceptable for Jeff to spend a few days at their place: Tim would be leaving soon on tour, but had some free time. It was the start of the Easter break, so Mary agreed. Next morning, she packed Jeff’s clothes in a brown paper bag and drove him to Santa Monica to spend his most extended period of time with his father.

Tim and Judy lived a few blocks from the beach. As Jeff remembered it, the following five days - the first week of April 1975 - were largely uneventful. “Easter vacation came around,” he wrote in 1990. “I went over for a week or so, we made small talk at dinner, watched cable TV, he bought me a model airplane on one of our 'outings’ … Nothing much but it was kind of memorable.” Three years later, he recalled it with much more bitterness: “He was working in his room, so I didn’t even get to talk to him. And that was it.”

Mary recalls Jeff telling her that he would dash into Tim’s room every morning and bounce on the bed. At the end of his stay, Tim and Judy put Jeff on a bus out of Santa Monica, and Mary picked him up at the bus station in Fullerton. When Jeff stepped off, she noticed he was clutching a book of matches. On it, Tim had written his phone number.

By his teens, Jeff was exhibiting impressive musical skills, as another school band member, drummer Paul Derech, discovered when he visited Jeff in the Guibert home in early 1982. Sitting on his bed, Jeff played songs from Al Di Meola’s Electric Rendezvous and the first album by Asia. Even though Derech had to listen closely to Jeff’s guitar - Mary couldn’t yet afford an amplifier for her son - his dexterity was so apparent that Derech literally took a step back.

Once, Jeff pulled out a picture of Tim from his closet and softly said, “I’ve spent a lot of time looking at that picture”, before moving on to another topic. Derech, like other kids, sensed immediately that his father was a sore point. Instead, they talked music. Although punk and new wave were the predominant rock styles of the moment, Jeff had little interest in them. He preferred music that challenged him and transported him to imaginary worlds. In the late 70s and early 80s, that music was prog (short for progressive) and art rock - bands such as Yes, Genesis and Rush that revelled in complex structures, science-fiction-themed lyrics and virtuosic, fleet- fingered guitar parts that only a few teenagers could hope to master. In a friend’s garage, Jeff and Derech soon began jamming on versions of Rush songs. Jeff declined to sing, though; he told friends and family he wanted to be a guitarist, plain and simple.

The reason, some felt, was because he didn’t want to be compared to the musician father he barely knew. “He had exactly the same speaking voice as Tim,” recalls Tamurlaine, the daughter of Herb Cohen, Tim’s one-time manager. She befriended Jeff when he and Mary would visit the Cohen family for dinner. (Cohen and Mary kept in touch after Tim and Mary’s break-up.) During those meals, Jeff’s vocal and physical resemblance to his father led Cohen often to mistakenly call Jeff “Tim”.

Jeff moved to New York City in 1990.

Often sporting his black Hendrix T-shirt, Jeff immediately took to New York, hauling his guitar into the subway to play for change and roaming the streets. “I talked to him right after he got to New York and he was loving it,” recalls his friend Tony Marryatt, a fellow student at Musicians Institute in Hollywood. “He said it was just like a Woody Allen movie.” To support himself, he took a series of day jobs, from working at an answering service (for actors such as F Murray Abraham and Denzel Washington) to being an assistant at a Banana Republic clothes store.

© David Browne 2001. This is an edited extract from Dream Brother: The Lives And Music Of Jeff And Tim Buckley

#jeff buckley#remember me? part 1#dream brother: the lives and music of jeff and tim buckley#david browne

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Y'all, I have a totally irrelevant official announcement.

So, this popped out in my YouTube stream today (lots of procrastination these days, I know) and honestly it was quite unwanted. But I watched it and HEY, it's the very first time KK doesn't scare the shit out of me. I deeply appreciate this piece and I think I'll bootleg it somewhere in my late Autumn soundtrack or whatever.

Not sure if this is about his fathering transformation or actually my own transformation, but thanks ginger dude for not making me feel awful about what you do. You're ace man, thank you for helping me change what I think of you in this annoying timeframe of overthinking and superfluous feelings.

0 notes

Text

Weekend Planner: 20 Awesome Things to Do in Los Angeles

Here are 20 of the coolest events happening in L.A. this weekend. Want the 411 on additional events and happenings in LA? Follow editor @christineziemba on Twitter or Instagram.

If you like what you’re reading, consider donating to PopRadarLA.com to help defray the costs of the site. Thank you!

FRIDAY, FEB. 2

GIRLSCHOOL FESTIVAL 2018 (Music + ideas)

Girlschool’s third annual woman-centric music festival returns to the Bootleg Theater this weekend (Friday through Sunday). Founded by Anna Bulbrook of The Bulls and The Airborne Toxic Event in response to the dearth of women in alternative music and festivals worldwide, Girlschool’s mission is critical. The schedule is filled with performances and afternoon talks, panel discussions and more. Highlights include a Friday keynote conversation between Carrie Brownstein (Sleater-Kinney, Portlandia) and poet Morgan Parker; Shirley Manson performing Garbage songs with string quartet, harp, the Girlschool Choir...and a “very special secret guest”; and sets by Jay Som, Bosco, Moon Honey and more. Day passes: $22-25. Weekend pass: $60.

AN INVITATION TO DANCE (Film series)

The Norton Simon Museum presents An Invitation to Dance, a film series that screens four films starring dance legends Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly every Friday in February at 5:30 pm. The series celebrates the many dancers on view in the current exhibition, Taking Shape: Degas as Sculptor. Screening this week: Top Hat (1935). The film is free with general museum admission ($12-$15).

CULTURE CLASH: SAPO (Film)

Culture Clash, one of the nation’s most prominent Chicano-Latino performance troupes, debuts SAPO at the Getty Villa on Friday at 8 pm. The production, based on Aristophanes’ The Frogs, features L.A.-based band Buyepongo, whose sound fuses cumbia, merengue, punta, jazz and funk. From the Getty: “Culture Clash’s riotous adaptation takes place in three epochs as it dissects three important elements inspired by Aristophanes’ original: An ancient journey on the road to Hell, recent fire storms near the 405 and an after party in the 1970's with a Latin rock band from the Bay Area also called SAPO (Frog), hoping to meet a record industry God but ending up somewhere between Malibu parties and the El Monte Swap Meet.” The show runs Fridays at 8 pm, and Saturdays and Sundays at 4 and 8 pm. Tickets: $20.

OFFICIAL MONTY PYTHON INSPIRED ART SHOW (Art)

Gallery 1988 holds an opening reception for an Official Monty Python Inspired Art Show at the gallery on Friday night from 7-9 pm. The group art show honors the British comedy troupe, and prints will be online and available for purchase the following day.

SWEET VALLEY GROUNDLINGS (Comedy)

The Groundlings present their newest stage show Sweet Valley Groundlings, following the gang’s typical teenage stuff every Friday and Saturday night. The show opens on Friday night at 8 pm, and this show features bites catered from The Darkroom. Sweet Valley Groundlings runs Fridays at 8 pm and Saturdays at 8 and 10 pm through April 14. Tickets: $50 for opening night; all other shows are $20.

MEOW MEOW / THOMAS M. LAUDERDALE (Cabaret)

UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance (CAP UCLA) presents torch singer Meow Meow in concert with Pink Martini founder and pianist Thomas M. Lauderdale on Friday at The Theatre at Ace Hotel on Friday night at 8 pm. Get ready for a night of music, comedy and mayhem and a century-spanning repertoire. Tickets: $29.50–$69.50.

Classic Photographs Los Angeles 2018 opens at Bergamot Station this weekend. | Image: Julie Blackmon, 'Lost Mitten,’ 2010.

CLASSIC PHOTOGRAPHS LOS ANGELES 2018 (Photo)

The 9th edition of Classic Photographs Los Angeles 2018 returns this weekend to Bergamot Station in Santa Monica. Discover, browse and/or buy the best in vintage and contemporary photography from 30 dealers from the U.S., Canada and Japan. Free admission. The opening night preview takes place on Friday night form 6-8 pm.

“FIGHT FOR YOUR RIGHT REVISITED” / AWESOME; I FUCKIN’ SHOT THAT (Film)

American Cinematheque presents the series, 10 Years of Oscilloscope Laboratories: A Weekend of Celebration, beginning on Friday night at 7:30 pm. Oscilloscope Laboratories, founded by Adam Yauch (MCA of Beastie Boys fame) and David Fenkel (co-founder of A24), is noted for its esoteric film choices for distribution and production. The opening night features Fight for Your Right Revisited (2011, directed by Yauch), followed by Yauch’s Beastie Boys concert film, Awesome; I Fuckin' Shot That! A discussion follows with Mike D and Ad-Rock of the Beastie Boys, and Fight for Your Right Revisited cinematographer Wyatt Troll. Special Ticket Prices: $20 General, $18 Students/Seniors, $15 Cinematheque Members. No vouchers.

FIRST FRIDAYS (Science + music)

The Natural History Museum’s First Fridays returns for 2018 on Friday with the theme, L.A. Invents: A Becoming Los Angeles Series. The programs explore the intersection of nature, culture and creativity in LA. Longtime veteran journalist Patt Morrison returns to moderate and host the series, and Friday’s performers include Phoebe Bridgers at 8 pm; John Doe and Exene at 9 pm and DJs KCRW Resident DJ Anthony Valadez and DJ Reflex. Tickets: $20.

SANTA BARBARA INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL (Film fest)

If you want a little mini-road trip this weekend, then head north to the Santa Barbara Film Festival, which runs through Feb. 10 at the Arlington Theatre. The festival showcases films representing 58 countries and includes 45 world premieres, 53 U.S. premieres, along with tributes, panel discussions, and more. In addition to film screenings this weekend, tickets are still available for a Gary Oldman ($35) tribute on Friday and a Saoirse Ronan tribute ($20) on Sunday. Saturday’s Virtuosos Award honoring Daniel Kaluuya, Gal Gadot, Hong Chau, John Boyega, Kumail Nanjiani, Mary J. Blige and Timothée Chalamet is sold out.

SATURDAY, FEB. 3

ICE CREAM FOR BREAKFAST DAY (Food + politics)

Saturday is Ice Cream for Breakfast Day, and to mark the occasion, all Jeni’s Splendid Ice Creams scoop shops open their doors three hours early on Saturday, donating 50% of sales from 9am to noon to She Should Run, a nonprofit organization that is working toward getting 250,000 women running for elected office by 2030.

SMORGASBURG DUMPLING DAY (Festival)

The first Smorgasburg Dumpling Day comes to Santa Anita Park on Saturday from 12-4:30 pm. Come to the park for horse racing, beer and dumplings from Workaholic, Brothecary and more. Buy the Dumpling Package ($30) and get an order of dumplings, one craft beer, a $5 betting voucher, club house admission, program and tip sheet, and trackside and grandstand seating. A 4-pack package will set you back $110.

PANTIES ON A BUDGET: COUPLES THERAPY (Comedy)

The L.A. sketch comedy troupe Panties on a Budget brings back its Couples Therapy show to the Ruby Theater at The Complex this Saturday and next at 8:30 pm each night. The show focuses on a couples theme: first dates, longtime married couples, old friends and coach/athlete. This show includes sketch comedy, theater and audience interaction. Tickets: $10-$15.

GIANT ROBOT: AUTOKITE (Art)

Giant Robot presents AutoKite, a solo art exhibition by Jacky Ke Jiang aka AutoKite. His portfolio includes industry work for the Walt Disney Animation Studio, Cartoon Network, and illustration, animation and art direction on the game Sky: Light Awaits. There’s an artist’s reception on Saturday night at GR2 Gallery from 6:30-10 pm. The show runs through Feb. 28.

Movement + Narrative is a group art exhibition that opens this weekend.| Image: Andrew Hem, 'All The Way Low' 2017, Acrylic on linen, 25 x 36 inches, Courtesy of sp[a]ce gallery.

MOVEMENT + NARRATIVE (Art)

Movement + Narrative is a group art exhibition, curated by F. Scott Hess, that opens at sp[a]ce gallery at Ayzenberg in Pasadena on Saturday. Artists include: Alla Bartoshchuk, Carl Dobsky, John Griswold, Kenny Harris, Andrew Hem and others. “The works in this exhibition promote interwoven themes of movement and narrative, with perceptions of the former creating the latter.” The opening reception takes place on Saturday from 6-9 pm, and the works remain on view through March 11.

THE WORKJUICE PLAYERS: UNDER COVER (Comedy + variety)

The Thrilling Adventure Hour's WorkJuice Players [Busy Philipps, Janet Varney, Autumn Reeser, Mark Gagliardi, Annie Savage, Marc Evan Jackson] and surprise guests sing their favorite songs about songs in a special benefit for Education Through Music LA at Largo on Saturday night. Doors at 7 pm, show at 8 pm. Tickets: $30.

DEMETRI MARTIN (Comedy)

Comedian Demetri Martin plays The Theatre at Ace Hotel on Saturday night as part of his Let's Get Awkward Tour. Doors at 7 pm, show at 8 pm. All ages. Tickets: $39.75-$49.75.

youtube

STRFKR + REPTALIENS (Music)

On Saturday and Sunday, Reptaliens and STRFKR play a sold-out Teragram Ballroom. Get there early for Reptaliens—the husband and wife team of Cole and Bambi Browning—before headliners STRFKR Doors at 8 pm, show at 9 pm. All ages. Tickets: $26-$30.

SUNDAY, FEB. 4

SUPER VEGAN SUNDAY (Food)

On Sunday, Smorgasburg LA teams up with Eat Drink Vegan and Vegan Street Fair to bring you the first Super Vegan Sunday at Smorgasburg LA. The event features 12 popup vegan vendors, including Amazebowls, Donut Friend, Senorita, curated by Eat Drink Vegan and Vegan Street Fair, with more than 35 other weekly Smorgasburg LA vendors offering special vegan dishes for the day.

THE BLACK BOOK, VOLUME IV: BLACK LOVE IN THE HOUR OF CHAOS (Talk)

The Hammer Museum presents The Black Book, Volume IV: Black Love in the Hour of Chaos on Sunday at 3 pm. Writers Tisa Bryant and Ernest Hardy use film clips, music videos, excerpts from literature and social media to celebrate black love in all its forms. From the Hammer: “This dense but fast-moving presentation looks at the creation, manifestation, nurturing, and resilience of black love in the face of white supremacy and anti-blackness across generations.” Free.

0 notes

Text

Inger Lorre celebrates

Infamous Nymphs front woman Inger Lorre celebrates how vital her songs still sound today, with a live recording album 'Live at the Viper Room' of a sold-out at the legendary Viper Room, due out on August 4th, 2017 via Sweet Nothing / Cargo Records as CD and 2 LP set (coloured vinyl). The set includes classic Nymphs tracks, ‘Sad & Damned’, ode to a serial killer ‘The Highway’ and the mourning swirl of ‘Imitating Angels’, with the addition of a cover of a Siouxsie’s ‘Monitor’. This ‘official bootleg’ is as raw and primal; tribal, glamorous, witch-y, grunge-y, punk. Inger states, “These songs are the sound of me walking through fire...”

Track listing:

1. Rumble 2. Alright 3. Death Of A Scenester 4. Sad & Damned 5. 7B 6. Snowflake 7. Hate In My Heart 8. Wasting My Days 9. 2 Cats 10. The River 11. Imitating Angels 12. The Highway 13. Monitor

“Inger retains her strength as a songwriter and performer without losing any of her sensitivity, fragility and danger. I always look forward to what she does, it never disappoints” - Henry Rollins

"The Nymphs were a very original underground band with a unique sound and GREAT songs" - Iggy Pop

“Inger Lorre is a magician, a shaman…that kind of witch-doctor ability for live performing” - Eric Avery, Jane’s Addiction

The Players:

Inger Lorre - Vocals (The Nymphs) Eric James Contreras - Drums (The Bloodhounds, The Nymphs, Plant Tribe) Gabe Hammond - Bass (The Fuzztones) Sean Romin - Guitar (The Generators, Schleprock) Mario Tremaine - Guitar (The Nymphs)

Lorre’s cult following has grown in strength of late, with the seminal self-titled debut album re-issued by Rock Candy Records and 2 new songs released for Record Store Day. Encouraged by the interest she is recording a new album, tentatively planned for an autumn release.

Often seen as musician’s musician (once dubbed by Jeff Buckley as ‘The Patron Saint of Fucked-Over Musicians’) and having worked with the likes of Iggy Pop and Henry Rollins, sadly Inger’s notoriety often eclipsed her darkly beautiful music.

Haunted by the infamy of a band that burned brightly all too briefly, before imploding in a devastation of bereavement, addiction, and mental health issues and misguided record company dealings. No one will ever forget the desk pissing incident. Inger Lorre is a music industry legend.

These days Inger Lorre has mostly conquered her own demons - exorcised through art, music and time to heal. What comes next will no doubt be unique as the women herself.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inger_Lorre

0 notes

Text

Fugazi: In on the Kill Taker

If 1991 was The Year Punk Broke, and 1993 was when the underground had fully bubbled to the surface, between that, the world got Cliff Poncier, the singer of the band Citizen Dick in Cameron Crowe's 1992 movie Singles. Cliff (played by Matt Dillon) is a musician in a band with Eddie Vedder, Stone Gossard, and Jeff Ament of Pearl Jam, and has an album out on an independent label. To a large swath of America that was still getting used to Kurt Cobain’s face and R.E.M. winning Grammys, Cliff was the fictional bridge into the world of indie artists. He’s “like a renaissance man” we’re told, but it’s obvious he wants to make it big. Everybody wanted that, right?

Alt was the new normal. Things had gone from “Our band could be your life” to stadium concerts opening up for rock legends and poisonous major label contracts. Nirvana followed up Nevermind with the Steve Albini-produced In Utero, former SST bands Dinosaur Jr., Sonic Youth, and the Meat Puppets enjoyed radio and MTV airtime, countless kids got copies of the No Alternative compilation, and grunge was officially a runway style thanks to Marc Jacobs. Fugazi’s independent scene had become a global phenomenon, funded, largely, by corporate money.

Fugazi—reluctantly—turned into one of the last bands standing from the old guard of American punks. They became a band that mainstream kids and college radio stations wanted to check out at the perfect time in their career. Fugazi’s nonstop touring made their music more accessible to a wider audience than ever before. They had an organic buzz that led to better distribution deals, which allowed them to remain fiercely independent. To kids straddling the Generation X and Millennial borders, Fugazi were a touchstone, an introduction into the DIY mindset. Their ability to get people excited without a team of advertisers, big hit song, or anything besides word of mouth is, at this point, the stuff of legend.

And while their hardcore contemporaries were chasing big contracts and slots on the Lollapalooza tour, Fugazi teamed with groups like Positive Force—a Washington D.C. youth activist collective that took on poverty and George H.W. Bush’s war in the Middle East—to the band’s decision to only play all-ages shows with a low door price, Fugazi wanted to let you know they stood for things, and that maybe you should, too. Punk was more than just not knowing how to play an instrument but having something to say, it was about starting a zine, doing distribution, or going to a protest to fight inequality in all its forms. They were champions of the utopian freedom of the 1960’s filtered through the busted amps of punk. If there was any environment for Fugazi to put out the biggest record of their career, this was it.

Since the band considered live shows to be their most natural setting, Fugazi toured relentlessly between albums. One look at the band’s show archives finds them playing the Palladium in New York City to 3,000 people on a spring night in 1992, Father Hayes Gym Bar in Portland, ME to 750 people a few nights later, then wrapping up an East Coast tour at City Gardens in New Jersey to a hair under 1,000 before embarking on a tour of Europe two weeks later. At some point during 1992, even though none of the band’s 73 shows were played anywhere near the Midwest, they found time to go to Chicago to record with Steve Albini. Self-producing their second LP Steady Diet of Nothing left the band “pretty disappointed at the end of the day with that record,” as Ian MacKaye would later say. Bassist Joe Lally found the experience “weird,” and that going to Chicago to record new songs was less about getting a new album out of the sessions, “it was more about working with Steve.”

The resulting demos were not what the band or producer wanted. The song “Public Witness Program,” had the same buzzsaw guitar and sped-up tempo of what you’d expect from one of Albini’s own Shellac songs. “Great Cop,” sounded much more like a raging hardcore song than the band may have wanted. The sessions, which float around file sharing sites and YouTube, would end up being simply a footnote in American indie history; titans from the 1980s underground getting together to mess around. In the end, after they made it back home to D.C., the band received a fax from Albini saying, “I think we dropped the ball.”

The band just couldn’t beat the sound they created in their hometown, so they entered Inner Ear Studios with Don Zientara and Ted Niceley in the autumn of 1992. When they finally emerged playing their first show on February 4th, 1993, at the Peppermint Beach Club in Virginia Beach, the 1,200-person crowd got a set filled with almost all new material, peppered with older songs like “Suggestion” and “Repeater.” The band went on an American tour that stretched over 60 shows. In on the Kill Taker was released on June 30th, sold around 200,000 copies in its first week alone, and Fugazi cracked the Billboard Top 200. Later in August, they played a show in front of the Washington Monument to celebrate the 30th anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King’s march on Washington. Five-thousand people crowded the outdoor Sylvan Theater and this time, when they played their new songs, the crowd knew every word.

Like the albums that came before it, In on the Kill Taker begins small and grows into something larger. Maybe it’s a metaphor for how Fugazi sees the world, or at least the one they helped to build: “Facet Squared” opens with a few seconds of near-silence that builds into feedback, then some guitar mimicking a heartbeat checks in at the 15-second mark, joined in by the rest of the band who work together building up what sounds like it will be a slow jam with no real leader. The guitars, along with Joe Lally’s bass and Brendan Canty’s drums, all work together like a machine. MacKaye’s guitar takes over for a few seconds, signaling the next level the song is about to take. That buildup leads to one of MacKaye’s most furious deliveries as a singer, opening by claiming, “Pride no longer has definition,” with the kind of energy and anger he channeled in his younger days with Minor Threat. The song ends and cuts right into Canty pounding away to start the Guy Picciotto-fronted “Public Witness Program.” Complete with handclaps, a ringing chorus, and Picciotto yelling, “Can I get a witness” like a punk preacher; it showcases the band at their most driving. This is the closest you get to a polished Fugazi record, but by no means is it slick.

MacKaye, in an interview for Brandon Gentry’s book Capitol Contingency: Post-Punk, Indie Rock, and Noise Pop in Washington, D.C., 1991-1999, believed that little bit of shine was intentional, the result of producer Ted Niceley reacting to what he heard from the popular bands with the same DNA as Fugazi that were getting heavy airplay. “It’s that consciousness of radio,” MacKaye said, “that puts me off a little bit,” while also railing against the producer’s “total fixation on detail.” Yet it’s exactly that consciousness of radio and fixation to details that gives In on the Kill Taker its real edge. It’s hard to imagine a song like “Cassavetes,” with Picciotto conjuring up the ghost of the dead director, screaming, “Shut up! This is my last picture,” being sandwiched between the Smashing Pumpkins and Candlebox on a radio station’s playlist. The extra lacquer on top only makes it more scathing and visceral.

There’s no single on In on the Kill Taker. Besides “Waiting Room” somehow becoming one of the defining Gen. X anthems, Fugazi never set out to make any one song hold any more importance over the others to try and get radio program directors to pay attention. In fact, on their third album, they threw all curve balls, going from fast and hard to slow to mathy and instrumental. Of course, it didn’t hurt that Picciotto and MacKaye had helped lay the foundation for the hardcore and emo scenes in the ’80s with Rites of Spring and Minor Threat respectively. The roots of Fugazi were blooming out into hundreds of sub-genres and taking hold in regional scenes across the country. Fugazi appealed to such a vast swath of people, something a lot of punk, hardcore or indie bands couldn’t claim in 1993, and In on the Kill Taker had something for everyone.

Songs like “Smallpox Champion,” again with that slow start that builds, then blows up into Picciotto delivering a sermon, railing against America being a country founded on genocide, “The end of the future and all that you own.” While “23 Beats Off” sounds like a song from Wire’s early years literally stretched and pulled out to nearly seven minutes, MacKaye going from singing (as best he can) to screaming about a man who was once “at the center of some ticker tape parade,” who turns into “a household name with HIV.” You get a dose of the past, present, and future listening to these twelve tracks.

Lyrically, it’s also one of the more ambitious albums from the era. While burying any meaning beneath a pile of words like Cobain or bands like Pavement were so fond of doing was certainly du jour, Fugazi liked to mix things up. Picciotto flexed that English degree he got from Georgetown, while MacKaye’s muses were Marx and issues of The Nation. The band blends political with poetic, while sometimes erring on the side of the latter. If there’s any deeper meaning behind “Walken’s Syndrome,” besides being an ode to Christopher Walken’s character in Annie Hall, it’s difficult to tell what that is. “Facet Squared,” with MacKaye singing about how “flags are such ugly things,” could either be about nationalism or the facades people wear when they go out in public, you pick. Maybe that’s what they wanted the listener to do.

Fugazi were so unbelievably popular that it was more so the idea of Fugazi had caught on like it was just another adjective like goth or grunge. Even with their famous anti-merchandise stance, an entire small economy of bootleg shirts popped up, including the infamous “This Is Not A Fugazi T-Shirt” t-shirt. The press also took even more notice. Rolling Stone, in a positive review, said Fugazi had inherited the title of “The only band that matters” from the Clash, while Spin wasn’t so hot on it, calling the members “radical middle-class white boys” and the album “rigid, predictable.” The food critic Jonathan Gold, whose music writing tends to be overlooked when discussing his oeuvre, gave it three out of four stars in his LA Times review. In on the Kill Taker wasn’t hailed as a masterpiece or an album that was changing the game, but everybody needed to weigh in on Fugazi.

And as a profile that came out in the Washington Post a month after the album’s release showed, everybody wanted to be associated with them. The article mentions fans like Eddie Vedder, “rock’s couple of the moment,” Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love, and Michael Stipe, who shows up to one of the band’s shows in Los Angeles: “He dances the hokey-pokey in the street in front of the Capitol Theatre with Fugazi drummer Brendan Canty,” in a very 1990s moment. In on the Kill Taker isn’t brought up until somewhere near the bottom of the piece. It was almost like saying that you liked or knew them was like a badge of honor, it absolved you of your own sins. The music was eclipsed by the message.

Mainstream interest in Fugazi was never as strong as it was during the period surrounding their third album. Two years later, when they released Red Medicine, the spotlight had shifted to pop-punk bands like Green Day and the Offspring. Fugazi continued to put out albums and pack shows that usually cost around five dollars, but the press was less interested in figuring out this crazy band with their wild set of ideals.

Many of the people who did pay attention to Fugazi, however, reacted. Like Brian Eno said of the initial 10,000 or so people who heard the Velvet Underground when their first album came out, the hundreds of thousands of people who bought In on the Kill Taker or saw the band as they trekked across America, Canada, Japan, Australia and New Zealand, that year and beyond, were impacted in some way. Maybe it was one kid out of 1,200 in attendance on September 27th, 1993 who saw them in Philly with the Spinanes and Rancid, or another of the 100 who saw them in Kyoto, Japan. Maybe a 15-year-old girl read about them in a magazine, this band that everybody was talking about, and decided to start her own band. Maybe it was a kid in El Paso, or a kid in Iowa City, or Greensboro. Maybe they inspired another kid to start a zine, which led them to realize they wanted to be a writer. Maybe 10,000 teens were so moved by Fugazi in 1993 that the ideas the band lived and worked by were ingrained into how those people have tried to go out and face the world.

0 notes