#Audata

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

What was Alexander’s relationship with his sisters like?

Short answer: We mostly don’t know.

Alexander and His Sisters

Longer answer: We have some clues that he may have got on well at least with Kleopatra and Thessalonike. Kynanne is more of a crap-shoot, as she was married to his cousin and rival, Amyntas. But as Philip arranged that marriage, she had little/no say in the matter, so we just don’t know what she thought of her husband-cousin versus her brother. (Not addressing the infant Europe, as she died at just a few weeks.)

First, let me link to an article by Beth Carney, and at the end, I’ll add some links to my own prior entries that address the question too.

Elizabeth Carney, “The Sisters of Alexander the Great: Royal Relics” Historia 37.4 (1988), 385-404.*

Beth’s article discusses Argead marriage policies, and the fate of the women after ATG’s death. I know she’s changed her mind about a few things, but it’s still well worth reading.

Also, a general reminder to folks who may be new to Alexander/Macedonia … Macedonian kings practiced royal polygamy: e.g., they married for politics, not love, and had more than one wife at the same time. Philip married 7 women (the most of any Macedonian king), although there weren’t 7 wives living in the palace at once. There may have been as many as 5 at times, however.

Because of royal polygamy, they did not use the term basilissa (queen) until after Alexander’s death. The chief wife was the mother of the heir; she had the most power. Because of the rivalry inherent in such courts, a woman’s primary allegiance was to her son, not her husband. Her secondary allegiance would be to her father (if living) and/or brothers. This was not unique to Macedonia, but a feature of most courts with polygamous structures.

These are not love matches, although our later sources may present them as love matches. (These authors had their own ideological reasons for such characterizations.) Did love never come after marriage? Perhaps. It would have depended. Also, within the women’s rooms, wives may have allied with each other at points, particularly if several of them. If only two (as seems more characteristic in Macedonia, aside from Philip), they’d have been rivals seeking to produce the heir.

I state all that to explain why Alexander’s sisters may have courted their brother’s affection (and protection), after Philip’s death. Only Kleopatra had a son, and he was 12 at most at Alexander’s death.

In his final year, Philip married off Alexander’s older sister, Kynanne (d. of Audata, ergo half- Illyrian), and Alexander’s younger and only full sister, Kleopatra (d. of Olympias). Kleopatra’s wedding was literally the day before Philip’s assassination. The timing of Kynnane’s marriage is less clear, but Philip married her to Amyntas, his nephew (her cousin), some time after his own marriage to his last wife, Kleopatra Eurydike. Kynnane had a daughter by Amyntas, Hadea (later Hadea Eurydike). We’re not sure if she was born before or after her father’s execution by Alexander, but it does let us nail down her age to c. 12/13 at Alexander’s death.

After he had Amyntas executed, Alexander planned to marry Kynnane to one of his trusted allies, Langaros, king of Agriana, which lay north of Macedonia, between Paionia and Illyria. Agriana was arguably Paionian, but similar to Illyria. Ergo, this may show a bit of thoughtfulness on Alexander’s part, to match his sister to a man who wouldn’t attempt to trammel her. Recall that Illyrian women wielded more power and even fought in battle. Yet Langaros died (perhaps of injury) before Alexander could make good on that.

It would be the last time Alexander planned any nuptials for his sisters. In part because he invaded Persia not long after, but it wouldn’t have stopped him from summoning one of them if he’d really wanted to marry her off.

Kynanne raised her daughter Hadea in traditional Illyrian ways, which Alexander allowed (although he probably couldn’t have stopped her). After his death, she took off to Asia to see Hadea married to her uncle, (Philip III) Arrhidaios. Kynanne was murdered by Perdikkas’s brother Alkestas, because Perdikkas (then regent) didn’t want the marriage. BUT the army (who liked and respected Kynanne) forced Alkestas to allow it anyway. Hadea (now) Eurydike and Philip III Arrhidaios eventually fell under Kassandros’s authority/possession, where she/they opposed Olympias and baby Alexander IV (and Roxane).

It was inevitable that the co-kingship that followed ATG’s death wouldn’t hold, and Hadea, who clearly wore the pants, wasn’t about to step aside for her cousin Alexander IV. Nor did Kassandros want them to, as he could control them. He couldn’t control Olympias. Yet none of that would necessarily reflect how Kynanne and Hadea had felt about their brother/uncle during his lifetime.

So, we must say the jury is out on Kynanne’s relationship with Alexander.

But for Kleopatra and Thessalonike, I do believe we have enough hints that they cared for him and he for them.

Kleopatra’s husband (another Alexander, of Epiros) died in combat in Italy in 332—around the time Alexander was besieging Tyre and Gaza, or four years after their marriage. In that time, Kleopatra produced two children, a girl (Kadmea) and a boy (Neoptolemos). The girl was named to honor her uncle’s victory over Thebes,** which happened at the tail-end of 335. As Alexander of Macedon and Alexander of Epiros both left on separate campaigns in 334, the boy would have to have been fathered not long after Kadmea was born. (It’s possible that Alexander of Epiros didn’t get to Italy until 333.)

After Alexander of Epiros’s death, Kleopatra did not marry again, although after her brother died, she had a couple marriage offers/offered marriage herself. She was THE prize during the early Successor wars…the full sister of Alexander.

Two titbits might suggest she was close to him (even if he didn’t marry her off again). First, the name of her first child is for his victory, not one by her husband. Sure, Alexander of Epiros didn’t have a battle victory at that point to name her for…but he could have insisted on a family name. Instead, he let Kleopatra give the child a name celebrating Alexander of Macedon’s victory. I suspect she fought for that.

Second, an anecdote reports that when Alexander was told his sister was having an affair some years after she’d become a widow, he reportedly replied, “Well, she ought to have a little fun.” This, btw, was viewed as a bad answer…e.g., he didn’t properly discipline her. As Alexander was constantly used for moral lessons (good or bad), we should take it with a grain of salt. But it’s possible his approximate reaction was preserved and became fodder for moralizing about those wild, half-barbarian Macedonians from the north…couldn’t keep their women in check!

As for Thessalonike, data here is also circumstantial. She stayed with Olympias after Alexander’s death and was never married until after Olympias herself was killed by Kassandros—who then forced her to marry him to cement his claim to the Macedonian throne. She had a sad life, at least in her latter years. Her eldest son (Philip) wasn’t healthy and died not long after he became king. Her second son (Antipatros) and her last son (Alexandros) apparently hated each other. After Philip’s death, Thessalonike argued that Antipatros should co-rule with the younger Alexandros. So Antipatros killed his mother! (Matricide, folks, is SUPER-bad.) Then Alexandros killed Antipatros, and was eventually killed in turn by Demetrios Poliorketes.

Well, if Justin can be trusted, and there are problems with Justin. Ergo, it’s possible that internecine spate of murders didn’t go the way Justin reports.

Yet the naming of her youngest boy may tell a story, along with her insistence that he co-rule with his brother.

There’s also the legend of Mermaid Thessalonike, but we can’t take that as any sort of evidence.

Here are some additional posts that also talk about the sisters:

“Writing Kleopatra and Alexander’s Other Sisters” — Although aimed primarily at the novels, it obviously must deal with the girls as historical persons. Pretty short for me.

“What Philip Thought about His Other Children” — A sideways take on this same question. Not long.

“On Amyntas” — About Alexander’s older cousin, his real rival for the throne when Philp was assassinated. Also discusses Kynanne as a matter-of-course. Not long.

“On Kassandros” — Mostly about Antipatros’s son Kassandros, who had Alexander IV murdered, but also discusses Thessalonike, who he forced to marry him. Relatively long.

--------------------------------------------

* The link takes you to academia.edu, where, by clicking on Beth’s name, you can find more of her articles. Keep in mind the woman has something north of 150, many on women, PLUS a bunch of books. Not everything is uploaded due to copyright, but several of her older articles are, such as this one.

** It was something of a “thing,” at least in Macedon, for daughters to be named in honor of their father’s victories. Kynanne not so much, but Kleopatra means “Glory of Her Father,” and both Thessalonike (Victory in Thessaly) and Europe (Victory in Europe) reflected their father’s triumphs.

#asks#alexander the great#alexander the great's sisters#kleopatra of macedon#thessalonike of macedon#kynnane of macedon#hadea eurydike#philip II of macedon#philip of macedon#alexander of epirus#classics#ancient macedonia#ancient greece#alexander's sisters#ancient greek family relations

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

CSIRO Positions available across australia

CSIRO Industry PhD program scholarships: Multiple opportunities94678Various, AUSolutions Architect Genomics Machine Learning95944Sydney, NSW, AU +2 more…X-Ray Systems Project Scientist96292Sydney, NSW, AUCSIRO Postdoctoral Fellowship in 2D Material Quantum Emitters96226Sydney, NSW, AUEngineers and Developers | Computing and Software | Multiple Positions – SKA-Low Telescope92883Perth, WA, AUData…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

CYNANE // PRINCESS OF MACEDON

“She was Princess of Macedon and half sister of Alexander the Great. Her mother, Audata, trained her daughter in “the arts of war” in the Illyrian tradition. She was married once and widowed in her early life, and employed herself in the education of her daughter, Eurydice. Out of all royal Macedonian women in the Hellenistic Period, Cynane was one of only three to fight on the front lines. It was claimed that she killed an Illyrian queen in battle and is, in fact, one of the only women recorded to have killed an enemy in battle. She also defeated an army of the now dead Alexander the Great when facing Alcetas. Cynane met her doom against Alcetas after the second time, and his troops rioted.”

1 note

·

View note

Photo

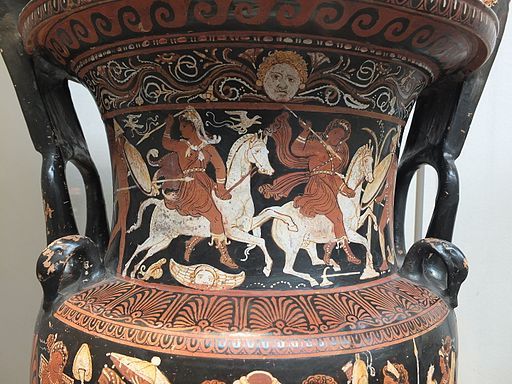

1. Cover image from Eurydice and the Birth of Macedonian Power by Elizabeth Carney

2. The Priestess Of Bacchus by John Collier

3. The Amazons : lives and legends of warrior women across the ancient world by Adrienne Mayor (pp.67–8)

#Cynane#Audata#Eurydice#King Philip II of Macedon#King Philip II#Alexander the Great#Vergina#John Collier#Adrienne Mayor#Elizabeth Carney#Amazons

0 notes

Text

Cynane Audata! A knight princess sort of person 💕 she’s really awkward but sweet

(+under the helmet)

#ocs#originalart#original characters#original art#original character#oc art#oc: Cynane#oc#my art#my ocs#png#art

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cynané

Cynané (alias Kynané, c. 357- 323 av. J.-C.) était la fille de la princesse illyrienne Audata et du roi Philippe II de Macédoine, ce qui faisait d'elle la demi-sœur d'Alexandre le Grand (356-323 avant J.-C.). Conformément à la tradition illyrienne qui voulait que les femmes soient des guerrières, sa mère l'éleva dans les arts martiaux et dans la conviction qu'elle était l'égale de n'importe quel homme.

Lire la suite...

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notes en vrac : Guerrières de mères en filles

Depuis que j’ai mis en ligne ma chronologie, je m’amuse à faire des liens et des parallèles. Voici quelques unes des observations que j’ai faîtes.

Dans les faits, l’appartenance à une famille militaire est dans de nombreux cas ce qui a permis à ces femmes d’acquérir leurs compétences. On s’imagine alors une transmission de père en fille, comme on le voit souvent dans la fiction, avec un père indulgent qui déciderait d’élever sa fille comme l’héritier qu’il n’a pas eu. Mais y-a-t-il des cas où cette transmission s’est opérée de mère en fille ou du moins de femme à femme, ou bien où l’on trouve tout simplement des guerrières sur plusieurs générations ?

-Trois générations de femmes guerrières : Cynane (-357/-323), la demi-soeur d’Alexandre le Grand, avait appris l’art de la guerre de sa mère, la princesse illyrienne Audata. Elle a ensuite élevé sa fille Eurydice comme une guerrière.

-Les soeurs Trung (Ier siècle), héroïnes vietnamiennes, auraient quand à elles également appris de leur mère. Cette dernière est d’ailleurs l’une de leurs générales lors de leur révolte contre la domination chinoise.

-La mère de Mathilde de Toscane, Béatrice de Lorraine était également une commandante militaire et une femme d’état reconnue.

-Trois générations de femmes guerrières de nouveau à la fin du Moyen-Âge : Orsina Visconti, sa fille Antonia Torelli et sa petite-fille Donella Rossi.

-Isabelle la Catholique et sa fille Catherine d’Aragon ont toutes les deux joué un rôle de chef de guerre (bien sur The Spanish Princess a beaucoup exagéré la chose ;) )

-La mère de la reine Amina, Bakwa Turunku, a elle aussi été chef de guerre.

-La mère de la poétesse et épéiste chinoise Liu Shuying (née vers 1620, morte après 1647) a été supervisée par sa mère dans son apprentissage.

-Ma Fengyi, belle-fille de la générale chinoise Qin Liangyu, mène à son tour des armées au combat.

-Lors de la bataille d’Aizu en 1868, Nakano Takeko combat aux côtés de sa mère, Kôko, et de sa petite soeur Yûko.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cynane and Eurydice

(Sketch by @9musesandanoldmind)

So I’ve been weirdly preoccupied with these mother/daughter warrior queens here recently. Cynane was a half-Illyrian, half-Macedonian warrior queen who was daughter of King Philip II of Macedon and half-sister to Alexander the Great. Daughter of Illyrian warrior princess Audata, Cynane was trained in both Macedonian and Illyrian warfare, led soldiers into battle, commanded a full third of Philip and Alexander’s armies during their conquest of Greece, and stayed behind to keep the peace while Alexander led his armies into Persia.

Her daughter Eurydice, meanwhile, was seventeen at the time of Alexander’s death and made a major play for the title of heir to his empire. She was apparently skilled at making alliances with other major players, led troops into battle like her mother, and even raised her own army of veterans from the Macedonian army.

Sadly, both were killed during the Successor Wars following the breakup of Alexander’s empire. Cynane was murdered by Alcetas, brother of Alexander’s henchman Antipater, during what was supposed to be peaceful negotiations. Eurydice continued to be a political powerhouse following her mother’s death, later leading her army against Alexander’s mother Olympias and her allies. Uncomfortable with fighting against Alexander’s mom, however, Eurydice’s troops revolted, and she was imprisoned and forced into suicide.

I’ve thought about it off and on since this ask, and I kind of want to write a ‘what-if?’ historical novel where mother and daughter survive and go on to become victors, at least in the Aegean theater of the Successor Wars. Or, if I had any experience in game modding, I think it’d be interesting to use the ‘Wrath of Sparta’ campaign for Total War: Rome II as a Successor War campaign with Cynane and Eurydice as major characters.

For further reading, both are major players in Robin Waterfield’s Dividing the Spoils and get mentioned in Vicki Leon’s Uppity Women of Ancient Times and Adrienne Mayor’s The Amazons. I’ve never read Mary Renault’s Funeral Games, but I understand both are characters in it as well.

Big thanks as well to Telenia Albuquerque for the wonderful Patreon sketch!

#Telênia Albuquerque#Cynane#Eurydice#warrior queens#history's heroines#ancient history#Ancient Greece#Greek history#discussion

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

not even five ic posts in and audata has already threatened to murder two people, off to a wonderful start already<3

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Philip’s first wife, Audata, an Illyrian, educated her daughter Cynane and her granddaughter Adea (Eurydice). Cynane fought with her father in her mother’s native land and killed an Illyrian queen in combat. During the struggle for power following Alexander’s death, she hired a mercenary army with her own money, entered the contest, and was killed. Adea, defeated in battle by a warrior queen, Olympias, who imprisoned her, killed herself. She was nineteen.

From Eve to Dawn - Marilyn French

#From Eve to Dawn#Marilyn French#literatura#Audata#Cinane#reinas#guerreras#historia de la mujer#Grecia#Macedonia#feminismo radical

0 notes

Note

Which "side characters" to Alexander's story are you most interested in both as a historian and as a fiction author?

Well, Hephaistion is obvious. But my interests as an historian and as a writer are slightly different.

As an historian, I could wish for a more unbiased account of Perdikkas. Of Alexander's age cohort, he had the highest appointments at the youngest age. I suspect it owes to equally high birth. We aren't sure, but his father Orontes was probably the prince/once-king of the canton of Orestis. In the sources, he's poorly treated in part due to bad press from the Successor Wars.

Reputedly, he was arrogant and high-handed, and his own officers (led by Seleukos) killed him in Egypt. But was he that bad, or are these reports part of that bad press (and Seleukos's and Ptolemy's ambitions)? If he were a prince, perhaps his arrogance had cause. Alexander seemed to think he was the most competent of those who remained in Babylon and gave him the ring. Would he still have got it if Krateros hadn't been sent away earlier on his own mission? I suspect not, but we just don't know.

And then there's Krateros, who may also have hailed from Orestis and was probably a cousin of Perdikkas. But, again, we can't be sure. I'd like a better sense of Krateros, as well, to evaluate his place at court. Like Perdikkas, our sources attach a bias to him, but in his case, a positive one. I'm as suspicious of that as I am of the negative one assigned to Perdikkas.

After that, it's largely the women. Olympias, yes. But even more Kleopatra, Thessalonike, and Kynanna. Also Philip's mother Eurydike. I expect THAT woman was someone to be reckoned with. As was Audata, Kynanna's mother. And Hadea, the daughter/granddaughter. Roxana, and Darius's daughters.

Oh, I'd like to know a little more about Parmenion's family--where they came from originally (Pelagonia or not?), and the two younger sons. Philotas sucks up all the air in the room.

Last, I wish we knew more about Darius himself: who he was before being raised to the throne. My friend, Scott Oden, has decided to work on a novel about Darius, which I expect to be spectacular. He has a real talent for detailing the losing side with compassion and insight. If you've not read his novel, Memnon, I recommend it, or Men of Bronze. I think he'll do a great job giving Darius a fair shake.

Now, as an AUTHOR, my interests are similar, but I get to include fictional characters, such as Kampaspe. She may be mentioned in our sources, but was almost certainly a Roman-era invention. Also, you'll get to meet a priest of Ammon who'll travel with Alexander. While also fictional, Alexander must have had such officiants, as he regularly included Ammon in his sacrifices. And, of course, Kleopatra will continue as a voice and window on what's happening in Europe while Alexander is out gallivanting around Asia.

Last, there's a fellow in Athens you'll get to hear more about: Phokion. Plutarch wrote a life of him, in which he's portrayed as the last respectable Athenian general, and was nicknamed "the Good," in antiquity. In the novel, Hephaistion meets him in Athens, when he's there the second time, and he becomes one of (several) people Hephaistion corresponds with, besides Aristotle and Kleopatra.

Oh, I forgot…not a side character of Alexander, but I REALLY REALLY wish we knew more about Alexander (I) “the Golden.”

#asks#Alexander the Great#Other people in Alexander's orbit#Macedonian women#Perdikkas of Orestis#Krateros of Orestis#Kleopatra of Macedon#Kampaspe#Hephaistion#ancient Macedonia#Phokion

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

30 days of character development.

5. Who are your character’s friends and family? Who do they surround themselves with? Who are the people your character is closest to? Who do they wish he were closest to? What is their relationship like with their family?

dating: aranth repesuna, we all know this, etruria and the love of his life. the etruscans were the best civilization ever and we do not deserve them. ALL WOMEN ARE QUEENS, ROME

related to: asherah (utica) is his sister, azmelqart (tyre) is his father, bodashtart (sidon) is his grandfather, and batnoam (phoenicia) is his cryptid vodka uncle. the other phoenician colonies count as... cousins or something. anysus isn’t interested in pursuing relations since they’re all MEAN to him and don’t appreciate his WORK because yes they all are dependent on this young upstart financially and militarily but anysus could be a LOT WORSE ABOUT IT HE NEVER ASKED FOR THIS

he would have considered his own colonies children if they stayed around long enough. lilybaeum was close but anysus doesn’t get anything he wants

friends with: sekhet (egypt), his old babysitter! gives him mom advice. audata (illyria), hot pirate mom. has a sacred brosome with aedan, timandros, and ardashir (celts, macedon, and persia) since they all ally against the greco-romans together. and that’s how you measure true friendship

humans: he’s not in the city a lot so ayzebel is much closer to them. that’s why she’s identified with the much more important deity, tanit, almost a patron deity. finally a culture where the man isn’t more important, zeus. but specifically he does really care about the slaves in his life and the people running his merchant ships! he knows he’s EXTREMELY hard to work with and just kind of neurotic and depressing to be around so he pays them prematurely for any damages/freakouts

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amazon Names

With thanks to Adrienne Mayor, who wrote the list out for us in her book Amazons. I have excluded names outside of the Graeco-Roman world because of the focus on my blog.

It is questionable whether these names were ever really associated with actual Amazons, who were most likely part of the hordes of tribes from Skythia, near the Black Sea. Most of them are names the Greeks offered as names of Amazons. Skythia stretched out towards the area we know as Kyrgyzstan, and even as far as China. Adrienne Mayor’s book does a great job describing tales that cross the entire Asiatic range about women who are warriors and queens who led armies.

Some of these are names for women with full stories, such as Penthisilea. Others we only have them depicted on a stray fragment of a vase. These names can be understood as representing just how little we know, just how little survived of the folklore of the Ancient Greeks.

A few of these names are familiar in other contexts. You’ll find mention of an Amazon named Hekate, and another named Asteria, for example. These are not the same as the Titanesses that bore those names, near as we can tell.

Ainia: “Swift” or “Praise” (from a Greek terra-cotta fragment) Ainippe: “Swift of Praiseworthy Horse” (Greek vase) Alexandre: “Protector” fem. form of Alexander (Greek vase) Alkaia: “Mighty” (Greek vase) Alke: “Mighty” (Latin Anthology) Alkibie: “Powerful” (Quintus of Smyrna) Alkinoe/Alkinoa: “Strong-Willed” (Greek vase) Amastris: Persian princess, founder of Amastris (Strabo) Amazo: “Amazon” (Strabo) Amynomene: “Defender�� (Greek vase) Anaxilea: “Leader of the Host or Army” (Greek vase) Anchimache: “Close Fighter” (Tzetzes) Andro: “Manly” (Tzetzes) Androdaixa: “Man-Slayer” (Tzetzes) Androdameia: “Subdues or Tames Men” (Greek vase) Andromache: “Manly fighter” (Tzetzes, Greek vase) Andromeda: “Thinks like a Man” or “Measure of Man” (Greek vase) Antandre: “Resists Men” (Quintus of Smyrna) Antianeira: “Man’s Match” (Tzetzes, Mimnermus fragment 21a, Greek vase) Antibrote: “Equal of Man” (Quintus of Smyrna) Antimache/Anchimache: “Confronting Warrior” (Tzetzes) Antioche: “She who Moves Against” (Hyginus) Antiope: “Opposing Gaze” (Apollodorus, Diodorus, Plutarch, Hyginus, Pausanias, Greek vases) Areto: “Virtue” (Greek vase) Areximacha: “Defending Warrior” (Greek vase) Aristomache: “Best Warrior” (Greek vase) Artemisia: “of Artemis” (Persian? Herodotus) Aspidocharme: “Shield Warrior” (Tzetzes) Asteria: “Starry” (Diodorus) Atossa: “Well-granting” (Iranian, Hellanikos, Justin, Claudian) Aturmuca: “Spear Battle” (Etruscan name for Andromache or Dorymache; vase) Audata: “Lucky”, “Loud”, or in Latin “Daring” (Illyrian, Athenaeus) Bremusa: “Thunder” (Quintus of Smyrna) Caeria/Kaeria: “She of the War Band,” “Timely,” or “Hill/Peak” (Illyrian, warrior queen, Polyaenus) Camilla: fem. form of Camillus, “Noble Youth” (Etruscan, Volschi, Virgil) Calaeno/Kalaeno: “The Dark One” (Diodorus) Chalkaor: “Bronze Sword” (Tzetzes) Charope: “Fierce Gaze” (Greek vase) Chichak: “Flower” (Turkish, Book of Dede Korkut) Chrysis: “Golden” (Greek vase) Cleophis: “Famous Snake” (Diodorus, Curtius) Clete/Klete: “Helper” (Tzetzes on Lychophron 995) Cyme/Kyme: “Billowing Wave” (Diodorus, Stephanus of Byzantium, coins) Cynna, Cynnane, Kynna: “Little Bitch” (Illyrian-Doric, Alexander the Great’s half-sister, Polyaenus) Deianeira: “Man Destroyer” (Diodorus) Deinomache: “Terrible Warrior” (vase) Derimachea: “Battle Fighter” (Quintus of Smyrna) Derinoe: “Battle-Minded” (Quintus of Smyrna) Dioxippe: “Pursuing Mare” (Hyginus) Dolope: Thracian tribal name (vase) Doris: “Bountiful” or “Dorian” (vase) Echephyle: “Defending the tribe” (vase) Enchesimargos: “Spear mad” (Tzetzes) Epipole: “Outsider” (Photius) Eriboea: “Many Cows” (Diodorus) Eumache: “Excellent Fighter” (vase) Euope: “Fair Face” of “Fair Eyes” (vase) Euryale: “Far Roaming” (Valerius Flaccus) Eurybia: “Far Strength” (Diodorus) Eurylophe: “Broad Crest” as of a helmet, “Wide Hill” or “Broad Neck” (Tzetzes) Eurypyleia/Eurypyle: “Wide Gate or Mountain Pass” (Arrian cited by Eustathius, vase) Evandre: female form of Evandrus, “As Good as a Man” (Quintus of Smyrna) Glauke/Glaukia: “Blue-Grey Eyes” (Apollodorus, Hyginus, Scholia Iliad 3.189, Callimachus, vase) Gortyessa: from Gortyn, possibly meaning “enclosure”, town in Crete (Tzetzes) Gryne: an Anatolian town (Servius on Aeneid 4.345) Harmothoe: “Sharp Spike” (Quintus of Smyrna) Harpe: “Snatcher” or “Sickle-Dagger” (Silius Italicus) Hegeso: “Leader, Chief” (vase) Hekate: “Far-darting” (Tzetzes) Hiera: “Sacred” (Philostratus) Hippe: “Horse” (Athenaeus) Hippo: “Horse” (Callimachus, vase) Hippolyte: “Releases the Horses” (Euripides, Apollodorus, Diodorus, Pausanias, Quintus of Smyrna, Plutarch, Hyginus, Jordanes, vases) Hippomache: “Horse Warrior” (vase) Hipponike: “Victory Steed” (vase) Hippothoe: “ Mighty Mare” (Quintus of Smyrna, Hyginus, Tzetzes) Hypsicratea: “High or Mighty Power” (Valerius Maximus, Plutarch, Greek inscription) Iodoke: “Holding Arrows” (Tzetzes) Iole: “Violet” (vase) Ioxeia: “Delighting in Arrows” or “Onslaught” (Tzetzes) Iphinome: “Forceful Nature” (Hyginus) Iphito: “Snake” (vase) Isocrateia: “Equal Power” (Stephanus of Byzantium, Eustathius) Kallie: “Beautiful” (vase) Kleptomene: “Thief” (vase) Klonie: “Wild Rushing” (Quintus of Smyrna) Klymene: “Famous” (Hyginus, Pausanias, vase) Knemis: “Greaves” (Tzetzes) Koia: “Hollow” as in sky, “Inquisitive” female form of Koeus (Stephanus of Byzantium) Koinia: “of the People” (Stephanus of Byzantium) Kokkymo: “Howling/Battle Cry” (Callimachus fragment 693, a daughter of the queen of Amazons) Korone: “Crown” (vase) Kreousa: “Princess” (vase) Kydoime: “Din of Battle” (vase) Lampedo/Lampeto/Lampado: “Burning torch” (Callimachus, Justin, Orosius, Jordanes) Laodoke: “Receives the Host or Army” (vase) Laomache: “Warrior of the People or Host” (Hyginus) Larina: “Protector” (companion of Camilla, Virgil) Lyke: “She-Wolf” (Valerius Flaccus, Latin Anthology, vases) Lykopis: “Wolf Eyes” (vases) Lysippe: “Lets Loose the Horses” (Pseudo-Plutarch) Maia: “Mother” (Callimachus fragment 693, a daughter of an Amazon queen) Marpe: “She seizes” (Diodorus) Marpesia: “Snatcher or Seizer” (Justin, Orosius, Jordanes) Maximous: “Daughter of the Greatest” (Hellenized Latin) Melanippe: “Black Mare” (scholia on Pindar) Melo: “Song” (vase) Melousa: “Ruler” (vase) Menalippe: “Steadfast or Black Mare” (Jordanes) Menippe: “Steadfast Horse” (Valerius Flaccus) Mimnousa: “Standing in Battle” (vase) Molpadia: “Death or Divine Song” or “Songstress” (Plutarch) Myrine: “Myrrh” (Homer, Diodorus) Oistrophe: “Twisting Arrow” (Tzetzes) Okyale: “Swift” (Hyginus, vase) Okypous: “Swift-Footed” (vase) Orithyia: “Mountain Raging” (Justin, Orosius) Otrera: “Quick, Nimble” (Apollodorus, Hyginus) Palla: “Leaping, Bounding” (Stephanus of Byzantium, Eustathius) Pantariste: “Best of All” (vase) Parthenia: “Maiden, Virgin” (Callimachus, another daughter of an Amazon queen) Peisanassa: “She Who Persuades the Queen” Pentasila: Etruscan version of Penthesilea Pharetre: “Quiver Girl” (Tzetzes) Philippis: “Loves Horses” (Diodorus) Phoebe: “Bright, Shining” (Diodorus) Pisto: “Trustworthy” (vase) Polemusa: “War Woman” (Quintus of Smyrna) Polydora: “Many Gifts” (Hyginus) Prothoe: “First in Might, Swift” (Diodorus) Protis: “First” (Callimachus, daughter of an Amazon queen) Pyrgomache: “Fortress Fighter” (vase) Rhodogyne: “Woman in Red” (Aeschines, Philostratus, Persian queen) Sisyrbe: “Shaggy Goatskin” (Strabo, Stephanus of Byzantium) Skyleia: “Spoiler of Enemies” (non. Greek word on a Greek vase) Stonychia: “Sharp point, Spear” (Callimachus, daughter of an Amazon queen) Tarpeia: “Funeral urn” (Greek-Latin, Virgin) Teisipyle: “Gate or Mountain Pass” (vase) Tekmessa: “Reader of marks, signs, or tokens” (Diodorus, Homer) Telepyleia: “Distant gates or mountain pass” (vase) Teuta: “Queen” (Illyrian, Appian, Polybius) Thermodosa: “From Thermodon” (Quintus of Smyrna) Thero: “Wild Beast” or “Hunter” (vase) Theseis: “Establisher” female form of Theseus (Hyginus) Thoe: “Quick, Nimble, Mighty” (Valerius Flaccus) Thoreke: “Breastplate” (Tzetzes) Thraso: “Bold, Confident, Courageous” (vase) Toxaris: “Archer” (vase) Toxis: “Arrow” (vase) Toxoanassa: “Archer Queen” (Tzetzes) Toxophile: “Loves Arrows” (vase) Toxophone: “Whizzing Arrows” (Tzetzes) Tralla: “Thracian” (Stephanus of Byzantium, Eusthathius) Tulla: “Supporter” (Latin-Volscian, Virgil) Xanthe: “Blonde” (Hyginus) Xanthippe: “Palomino” (vase)

Sources:

Mayor, Adrienne. Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World, Princeton, 2016.

Images:

Krater with Volutes in Terracotta, Red Figure vase, Magna Graecia, ca. 330-320 BCE, now in the Musee Royal de Mariemont. Photo by Ad Meskens. Via Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mariemont_Greek_krater_03.JPG

74 notes

·

View notes

Link

It was 2012 when Keegan Bakker, an announcer on Melbourne’s Fox FM decided that instead of dealing with the daily frustration of outdated promotions management software, he would create his own.

Three years later he has added CEO to his job title.

His company, Audata, is the world’s #1 broadcast promotions management platform, used by every major radio station in Australia and making in-roads around the world.

Read more at: https://radioinfo.com.au/news/melbourne-tech-startup-revolutionises-radio-promotions-australia-and-abroad © Radioinfo.com.au

0 notes

Note

Do we know/ think that any of Philip's wives were friends with eachother? I understand that they would have been competing with eachother to secure their sons' positions, but it seems odd to live with four or five other women and not have some sort of rapport with any of them

Philip's Wives

It’s unclear—in large part because the ancient sources simply aren’t concerned with them. In fact, we only know the names of all seven because of a chance list made by Athenaeus [13.557b–e], quoting Satyrus, as two were childless, or at least, their children didn’t survive to adulthood so they’re never mentioned in the main sources.

Probably the best way to guess who might have been friendly, and who at odds, is to consider where each came from originally.

Because Philip married for political reasons, all his wives but the last were not from lower Macedonia, and not all would have spoken Greek, at least not at first. Audata, daughter or more likely granddaughter or grandniece of King Bardylis, was Illyrian. As she was royal, she may have been able to speak some Greek, but likely wasn’t fluent. If she was wife #1 (and I think she was), Philip likely married her when he originally submitted to Bardylis as a client king, after his brother’s death. She was sent to Pella to keep an eye on him. When Philip returned a year later with his army and kicked Illyrian butt, well… she would have ceased to be important, all the more so when she had a daughter, not a son.

Wife #2 was likely Phila, of the royal house of Elimeia, so she was related to Harpalos and that crowd. That’s why Philip married her: to bring in the southern Macedonian highlands and the famous Elimeian cavalry. Elimeia, like Lynkestis, had been independent, their capital of Aiani wealthy, trading with Corinth on the Western side of the Greek mainland. It wasn’t really until Philip’s day that they fell under Macedonian control. It’s possible she had a child, but that child died in infancy or childhood. In Dancing with the Lion, I did give her one (Menelaus who died as a toddler), but that’s fictional based on the likelihood that Philip had more children, but we know only about those who lived. It’s also possible we hear nothing else from Phila because she died in childbirth.

If Phila came to the women’s quarters right after Audata, perhaps when Audata was still her grandfather’s agent, there may have been little love lost between those two. Audata probably lorded it over her, especially if she was also pregnant (and Phila wasn’t). After the Illyrian star fell, it wouldn’t surprise me if Phila returned the favor, especially after Audata’s baby turned out to be a girl. Audata died before Alexander did, probably before he even left for Asia. Her daughter Kynanne later appeared to operate entirely apart from Olympias and Kleopatra (and Thessalonike), and even in opposition to them, to marry her own daughter by Amyntas (Philip’s nephew), Adea Eurydike, to Arrhidaios, and put her on the throne. Given Arrhidaios’s infirmary, no doubt Kynanne knew or assumed her daughter would be the real power.

So those are the first two, although the order isn’t certain. I follow Carney in putting Audata first.

The order of wives 3-5 is also disputed. Olympias is usually called wife #4, bookended by the two Thessalians—Philina and Nikeseipolis—based on Philip’s two campaigns there, and the probable birthdate of Thessalonike, versus Arrhidaios. She’s notably younger. Yet Satyrus’s list puts both women married together as part of Philip’s settlement of Thessaly in 358 after the death of Alexander of Pherae. The story that Philip named Thessalonike for his victory at the Crocus Fields in 353/2 hardly requires him to have married her mother that late. Nor does the fact Arrhidaios was so much older. Nikeseipolis would later die from childbirth complications, so it’s possible she may have had miscarriages before, or a difficult time getting pregnant. We don’t know precisely what killed her, but as her death followed the birth by a couple weeks, it may have been sepsis from an imperfectly delivered placenta.

Ancient sources can’t always be trusted for details, of course, but as each woman was a daughter of powerful families two cities at each other’s throats just then, it makes sense to me if he did marry them at roughly the same time. Because their families were at war, it’s highly unlikely they would have been friendly in the women’s quarters.

That would make Olympias wife #5, so she was probably the youngest. Of the four already present, Phila of Elimeia would have been her most natural ally, if Phila was still alive. Both were highlanders, and Aiani had trade contacts with the Molossai tribe in Dodona/Epiros, as both traded with Corinth. Athens dominated the Aegean sea, but Corinth dominated trade in the Adriatic. When Elimeia was independent, they had diplomatic relations with Epiros.

So of the first five, Audata probably stood alone, although she might have had some protection from Eurydike, who was likely half Illyrian herself. Then Olympias and Phila may have been friendly. Philina and Olympias probably weren’t, given the story about Arrhidaios. Even if Olympias had nothing to do with his condition, Philina may still have believed she did.

There may also have been another reason for bad blood between Olympias and Philina. A late (Roman era) story says that when Philip took Nikeseipolis as a new concubine, supposedly he did so as a result of love magic. Yes, love spells were a thing, and Thessaly was famous for her “witches.” Olympias had the young woman brought to her, and upon seeing and talking to her, she declared there was no witchcraft except the normal sort in her face and figure and comely manner. Interestingly, she doesn’t seem to have been jealous in the story.

There are a boatload of problems with the story, starting with the “concubine” part. (Macedonian royal polygamy confused Greeks, and later Romans.) Also, it would put Nikeseipolis as wife #5, not Olympias. Yet it might contain a hint that Olympias and Nikeseipolis got along. So that might be another reason Philina was no friend of Olympias.

In any case, Nikeseipolis was out of the picture by 353/2, and if she was married in 358, wasn’t there that long. We aren’t told, but it’s certainly possible that Olympias raised Thessalonike. Again, I don’t think Philina would have done so, due to the enmity between her family (Aleuadai) and Nikeseipolis’s, who was likely related to the notorious Jason of Pherae. (And yes, if your eye is sharp, that makes Alexander’s mistress Kampaspe related to Philina!) I find it even less likely that Audata would have raised her. So Phila or Olympias are the best candidates.

I also want to point out that these first 5 women were all married by Philip in his first few years. Again, assuming the earlier date for Nikeseipolis’s wedding. He came to the throne in 360, and Alexander was born in 356. Even if we assume he married Nikeseipolis after Olympias, it would have had to have been by 354. Ergo, there’s not a lot of daylight between weddings.

More than a decade (c. 341) would pass before Philip married again: Princess Meda, daughter of Kothelas, of the Getai, a Thracian tribe. Meda barely gets a mention, is clearly a peace price, and never had any (surviving) children. As the Getai were on the northern and inland side of Thrace, she may not have spoken much Greek. Many royal Thracians were fluent in Greek, but mostly tribes with trading ties to Athens or the Greek cities on the Black Sea coast. We have no idea what happened to her. Some, including Hammond, have argued that’s her buried in the antechamber of Royal Tomb II, based on (some) Scythian customs of wives following their husbands in death. It’s a shaky argument, imo. I don’t want to get into the argument over who is buried in “Philip’s Tomb,” so I’ll just say that, being childless, she likely became a ghost in the women’s quarters. In Dancing with the Lion, I have Myrtale take her under her wing as part of my “Olympias was not a bitch” campaign. 😉

Last, we have Kleopatra Eurydike, and we all know who her enemies were. As for friends? I doubt she had any. The real question is how many of the other six wives were left when she arrived?

Olympias had just fled with Alexander, and Nikeseipolis was dead. We also know Audata died at some point, probably (but not certainly) before Alexander took the throne. If Phila were still alive, as noted, I think she’d have been in Olympias’s camp. Meda is a crap-shoot, but she had little/no power. Philina may well have been ranged against Olympias, so if Kleopatra-E. had any “friend” among the other wives, Philina was most likely. Even so, as she was mother to a son, even if not the heir apparent, which might have made Kleopatra-E. see her as an enemy. Given the importance of her uncle, I doubt Kleopatra-E. believed she needed to make allies in the women’s quarters, which I tried to play on in Rise.

If/when I get around to book 3 in the series, King, you’ll see a lot more dynamics from Kleopatra’s perspective. It wasn’t just Alexander and Hephaistion who had a coming-of-age arc in the first two books. 😊

#asks#Philip of Macedon#Philip of Macedon's wives#Olympias#Audata#Phila#Philina#Nikeseipolis#Meda#Kleopatra Eurydike#Cleopatra Eurydice#Macedonian royal polygamy#royal polygamy#Philip II#Philip II of Macedon#Macedonian politics#royal women's quarters in Macedonia

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why do you think it took Alexander such a long time to *actively* go about making an heir? I understand that marriage in the early 20's was uncommon but that for him it was especially undiplomatic to tie himself down to one particular faction at court at the start of his reign. His father himself was very quick to marry into peace. Why did it take Alexander so long to address that issue? He could have officiated his union with Staitera whenever. Or had anyone he wanted at 25 after Issus.

First, I've been preparing for, then in New York for some cool things I'll talk about later. But it's slowed down my answers. (Now, I have to catch up for the time spent preparing, so I'll still be slow.)

Also, I realized I answered this once before, so here is the other (somewhat shorter) reply.

Argead Inheritance and Alexander’s (lack of) Heirs (Take II)

A lot of historians have asked why Alexander didn’t marry earlier and put off producing an heir. My own answer involves what I think were some unrecognized attempts mixed with bad luck. To really understand, however, we have to look at the behavior of prior Macedonian kings, and how the Argead Dynasty understood succession. Buckle-up Buttercup, this is a longer one. 😊

Let’s begin with Philip (II) and his older brother Perdikkas (III), the only two prior kings whose ages of first marriage we know or can reasonably guess. Let me also preface it by saying that while prior Macedonian kings sometimes had more than one wife, nobody had seven.* (The most I’m aware of are two, maybe three.) Philip’s military and political success led to an expansion on royal marriage in Macedon.

Perdikkas III ruled c. 5 years. We’re unsure how much older he was, but 2-3 years and possibly more. At his death, he had a son about a year old (Amyntas). We don’t know the name of Perdikkas’s wife, or when he married, but he was married at least 2 years. At his death, he would have been 25-30, probably closer to 30. My guess is he married after coming to the throne (for reasons I’ll skip as this is already long enough).

Philip married 5 times in his first 5-6 years; all were political. He was c. 23/24 when he came to the throne. For his first marriage, he wasn’t given much choice. Like Beth Carney, I consider Audata the first wife (not Phila), and he married her as part of a deal with Bardylis to prevent all-out invasion of Upper Macedonia following his brother’s death (along with half the Macedonian army) on a battlefield in Lynkestis. That marriage made him a client king.

This marriage may explain his rapid second marriage to Phila of Elimeia (independent kingdom until Philip). He probably contracted it shortly after to get the skillful Elimeian cavalry, et al., on his side for a second go at Bardylis just the next year. No grass grew under Philip’s feet.

In addition, Bill Greenwalt has proposed that Philip and Olympias were betrothed some years prior by their brother and uncle, respectively, when she was still a girl and he was in his teens—a backroom alliance against the threat of Bardylis. Obviously, it didn’t save Perdikkas. In 360, she still wasn’t old enough to bring to Pella, nonetheless, the alliance existed. Philip already had Lynkestis via his mother Eurydike. And—if Parmenion really was from Pelagonia—he also had that kingdom, if not via marriage/family. That’s a solid border against Illyria. (See map)

So, his first marriages/betrothal were driven by a need to deal with Illyria. His next marriages, a few years later, reflected a need to settle matters in Thessaly on his southern border. Marriage for him was all about securing the Macedonian borders. Those five marriages produced five surviving children from four wives—two of them boys.

He doesn’t marry again for almost a decade, and then it’s to settle matters in northern Thrace.

The last marriage, whatever our sources say, was also almost certainly political, but this time to address apparent internal conflict. We’re not sure what that was; it’s been lost to layers of drama involving Alexander and Olympias, but it probably owed to tension between Upper and Lower Macedonia—which hadn’t been united all that long.

So, Philip’s marriages were politically driven. He got children out of them, but that wasn’t the driving reason for him to marry—except possibly the last. Internal conflict or not, he may also have married again to father a “backup” heir, in case he lost Alexander and/or Amyntas in Persia (more below).

That’s the view of [royal] marriage Alexander grew up with: Macedonian kings marry for politics…not necessarily to secure heirs.

We must also review the crazy method of Argead inheritance.** ANY Argead male could hold the throne. There was a preference for the son of the prior king, or at least a prior king. There also seems to have been a preference for a son by the higher/highest status wife. Yet because any Argead could hold the throne, virtually no Argead king went unchallenged either at the beginning of, or sometimes later in his reign.

Supposedly, on his deathbed, when asked to whom he left his kingdom, Alexander replied, “To the strongest.” That pretty much sums up Argead inheritance.

For this reason, underage Macedonian heirs/kings usually didn’t live/rule long. The one “infant king” tale comes from an era before we have a surviving historical record to know how long he reigned, or if it were all legendary. The list of Macedonian kings before Amyntas I, father of Alexander I, may be semi-mythical, like early Roman kings. See image…helpfully numbered (by me). Stemma itself from In the Shadow of Olympus, E. N. Borza.

Alexander I (Persian Wars) had five living sons. The line of inheritance went through the third, Perdikkas II (Peloponnesian War era), then down to Archelaos…after that, things get a bit crazy until Amyntas III (Philip’s father). He descended from Alex I’s youngest son, which established a new line that lasted until Alexander IV. But in that time, because of the somewhat laissez-faire attitude towards who could inherit, we have a lot of internecine battles every time a king died, which thinned the herd.

The arithmetic of high infant mortality plus death in war meant Macedonian kings needed an “heir and a spare, and the spare’s spare.” Philip had that after his first spate of marriages: Alexander, Arrhidaios, and Amyntas (his nephew). That Arrhidaios was unfit became apparent only over time, but was still good to father sons.

When, post-Chaironeia, Philip prepared to invade Persia, he made a spate of royal marriages first. Arrhidaios’s betrothal was meant to get an Asian bridgehead/ally, but fell through thanks to Alexander’s meddling. Amyntas was given his cousin Kynnane, who wound up pregnant quickly. That turned out to be a girl, but it proved both were fertile: more children to come. This marriage may also have been a sop to keep Amyntas loyal. Kleopatra was married off to the king of Epiros to solidify one of Macedon’s closest allies and alleviate any insult to Olympias at Philip’s own final marriage.

As for that wedding, in addition to any internal politics, it gave him opportunity for another son. He had to consider the possibility that he could lose both Alexander and Amyntas in combat, and perhaps even himself, if it all were to go south. Arrhidaios was a stop-gap. An infant son back home could eventually take the throne.⸸

Yet the one person he does NOT prepare nuptials for? Alexander.

Why? He almost certainly planned to marry him to one of Darius’s daughters. He admitted as much when he dressed down Alexander for having offered himself to marry Pixodaros’s daughter in Arrhidaios’s place. That would have made an impression on Alexander, perhaps in shame: he was meant for royalty only.

When Alexander ascended the throne, he owed it to the support of the two most important men in Macedon: Antipatros and Parmenion…who, if not open enemies, each had their own factions. Both had eligible daughters, but to avoid giving one side too much power, he’d have had to marry both, or none at all.

OR, as Tim Howe has suggested, he might have decided to marry his father’s young widow.

It wouldn’t have been the first time in Macedonian history. And it explains, oh, so much better, why Olympias killed Kleopatra-Eurydike. Keep in mind, Kleopatra-Eurydike’s new husband was dead and she’d delivered only (another) girl mere days earlier. Olympias may have enjoyed her discomfiture at being sidelined more than her death.

Unless Alexander decided to marry her. She was almost certainly younger than him, and had proven fertile. Maybe he saw the marriage as a way to further solidify support. But it would have challenged Olympias’s status. I don’t know that’s what happened, but Tim makes a good case, and her decision to kill the girl to remove the threat then becomes intelligible rather than just bloodthristy.

When Mommy Dearest eliminated the option, young Alex was back to square one. Marry a daughter of Antipatros and of Parmenion, or stay unmarried. He chose the latter.

Yes, it left no heir to the throne (other than Arrhidaios), but he didn’t have any good options that weren’t also a potential political grenade. And unlike his father’s situation in 359/8, marriage wasn’t foisted on him. He could wait a few years, so he did.

But after Issos, the Persian royal family came into his possession, and by this point, he was 24, the same age his father had been at his first marriage. Pressure began to mount. Here were all these pretty Persian ladies…. PICK ONE. It wouldn’t have been just Parmenion saying so.

There’s been some recent speculation that he married Barsine, didn’t just take her as a mistress. While possible, I’m not sure it’s probable. She came with a lot of baggage for a first marriage. Making her his mistress, especially if a palakē, provided her with a respectable, recognized status, but still left the door open for a first marriage because….

As the asker alludes to, he almost certainly also bedded Statiera, Darius’s wife. Why marry the pony horse when you can have the racehorse? Oh, oops. She’s still married because her husband is still alive. How inconvenient.

So why didn’t he just declare her divorced and make it official?

Politics. However much he didn’t really understand Persian affairs of state, he understood optics, and general human reactions. Greeks and Macedonians would want him to bed the queen because that’s the ultimate piss-in-the-eye of the Other Guy. But after Issos, Alexander was hoping to bring other satraps over to him. By not touching Statiera or her daughters—at least at first—he presented himself as civilized and respectful. He even offered Darius his family back, on one condition. Surrender. Darius had to come as a suppliant to ask for them.

Of course, Darius refused. Nor did Alexander expect him to agree, but the required dance had been performed. When Darius began soliciting a new army, the tacit message was, “You can have the women.” ⸸⸸

While all these negotiations took place, Alexander had Barsine. Keep in mind, the letters would have taken weeks, probably months. The number of letters is unclear, but probably two each. The final exchange occurred sometime in the seven months of Alexander’s siege of Tyre.

Why do I say he was bedding Statiera, and (probably) planned to marry her? After all, Plutarch is adamant he was too chivalrous even to look at her again after their first meeting! Well, Plutarch also tells us—without apparent irony—that Statiera died in childbirth along with an infant son just a few weeks before Gaugamela…which was two years after Issos. That sure as hell wasn’t Darius’s kid. And no, nobody else would have been allowed to touch her. Plutarch lied. Why? It’s all part of his honorable “Sleep-and-sex-remind-me-I’m-mortal” Alexander. It’s also Plutarch who turns the marriage of Roxane into a “love-at-first-sight” affair.

In any case, I think Statiera was another marriage that Alexander planned, but fate prevented.

If we count back 40-or-so weeks from her death in mid-September of 331, that puts us in December of 332. Alexander had entered Egypt in November. It’s doubtful she accompanied him on the trek to Siwah, so his opportunities for impregnating her were at the beginning of his Egyptian stay, or towards the end. Keep in mind that while we know she died in childbirth, we don’t know if it was full term. Accounting for Siwah, she was probably either nine months or seven months along. As for when he started sleeping with her, probably any time after the final exchange of letters with Darius.

In the spring of 331, he left Egypt to return to Tyre before moving inland to find Darius. It may be here that he retired Barsine, sending her off to Pergamon (in Asia Minor). If that’s the case, Herakles definitely wasn’t his, as the boy was born some years later. In any case, by the time Alexander left Tyre, Statiera probably knew she was pregnant and would almost certainly have told him.

I think he held off marrying her until he could meet Darius again in battle (and kill him), which he assumed immanent. Yet the Macedonians had no concept of how big the interior was. And Darius wanted to draw Alexander onto the plains of northern Iran—but not too fast. He burned fields in front of the Macedonians partially, intending to leave them with enough food to continue, but not enough to fill bellies. He assumed a hungry army would be insubordinate, but underestimated both Macedonian discipline and Alexander’s scouting and intelligence. By September, Alexander had finally caught him up east of ancient Nineveh across the Tigris.

Then Statiera went into labor and died. BOOM, Alexander’s marry-the-wife plan fell apart for a second time, and he lost a potential heir in the process. Did a lack of food contribute to her death? Maybe. She’d had at least 3 healthy children, but was also in her mid/late 30s, possibly early 40s. Lack of food or not, an army camp would hardly be easy on an older woman in late pregnancy. (Had my first at 33; I can speak to that.)

But!, you may be wondering, even if Statiera had lived and Darius had died (as was Alexander’s ostensible plan), wouldn’t a baby born before marriage have been a bastard? Wouldn’t matter. First, given the cloistering of highborn Persian women, it’d be easy enough to lie about such things. Second, bastard or not, the child was still an Argead.

It would also explain why he didn’t marry immediately after Issos—nor after Gaugamela. Plan A died in the birthing bed, and Plan B, the daughters, were too young yet. Furthermore, it wasn’t over at Gaugamela. He’d have to chase Darius further….

He dropped off the girls in Susa for safe-keeping and went after Darius. Again, we must recall, he had no idea how long this would take. He probably assumed he’d be back in Susa in a year or so. Instead, he wouldn’t see Susa again for six.

In 327 (c. 3.5 years later). he finally decided to marry—for political reasons: to achieve peace in Baktria. Now pushing 30, and given how long everything had taken, he chose not to put it off any longer; he could always marry the princess later. Ironically, this marriage was not well-received by the army, although it wasn’t much different from his father’s marriages. Then again, we have no idea how Philip’s marriages were received at the time. I doubt the army was thrilled to have an armor-wearing, battle-trained Illyrian princess as Phil’s first bride.

Whatever the case, Alexander had a wife and, if we can trust the Metz Epitome, he lost little time getting her pregnant. But she miscarried (again, perhaps a boy). He just wasn’t having much luck fathering living children…perhaps because he kept dragging his women through tough conditions. One had a geriatric pregnancy and the other was probably 14-16: neither optimal ages.

In any case, as soon as he was back in Susa, he planned the mass weddings, at which he finally married Darius’s daughter, Barsine, as well as Parysatis, Barsine’s cousin. Within a year, he had both Roxane and Barsine pregnant, if not Parysatis.

So, we have to shed the moralizing of Plutarch’s narrative and evaluate what was really going on. Alexander may not have married till 29, but he probably angled for it at least once (Statiera) and possibly twice (Kleopatra-Eurydike) before that. Should he have stopped aiming for queens and just married a nice girl to pop out babies? Well, that’s essentially what he did with Roxana. Maybe he should have started there, back in Macedonia before he left, but he didn’t, and at 22, it wasn’t a shocking choice.

Yes, Macedonian kings certainly worried about heirs, but to produce an heir was not the primary way Philip, or Alexander, used marriage. It served political goals first, inheritance second.

———————

* To be fair, he didn’t have seven at the same time. We know one (Nikesepolis, Thessalonike’s mother) was dead before Philip married Meda (#6), and it’s quite possible the mysterious Phila of Elimeia (#2) also died young. At the time of his death, we can be sure only of Olympias and Kleopatra-Eurydike, although at least some of the others were likely still around. My guess is there were four-to-five wives in the women’s quarters in 336. (In Dancing with the Lion, there are four: Philina, Olympias, Meda, and Kleopatra-Eurydike.)

** An almost prohibitive amount of scholarly debate, most in article/book-chapter form, concerns whether or not Macedonia had a “constitutional monarchy,” and what—if any—say the army had in choosing a king. While some constitutionalists remain (M. Hatzopoulos most notably), these days the bulk of scholars (not in Greece) favor a position of “nomos” (custom) but no formal rules. For a bibliography of the debate, at least up through 2002, see Carol King’s chapter in Brill’s Companion to Alexander the Great (Roisman, 2003). A new Companion from Cambridge, edited by Daniel Ogden, is currently in the works, probably out in 2023, which will likely update the state of the scholarly conversation.

⸸ This is more or less what the army demanded at Alexander’s death: Arrhidaios for now as Philip III, along with infant Alex IV, who’d presumably go on to reign alone when of age. But by that point, ambitious generals were happy just to end the Argead Dynasty altogether and form their own. Like most underage Macedonian kings, Alex IV’s days were numbered, even as the last Argead. Once, the gloss of divine descent from Herakles might have saved him, but the Diadochi had grown too jaded—and too successful. They all thought themselves equally worthy.

⸸ ⸸ By ancient criteria, if a man surrendered his kingdom “just” to get his wife and children back, it would automatically tag him unfit to be king. Yes, even in Persia, where women had higher status overall. In the ancient near east, nobody’s life was more important that the king’s. Statiera would have been well aware of that, so Darius’s ‘betrayal’ was to be expected. In fact, she might have despised him if he’d agreed.

#asks#roxane#statiera#alexander the great#macedonian royal polygamy#ancient macedonia#alexander the great and marriage#kleopatra-eurydike#classics#tagamemnon

35 notes

·

View notes