#Astrologer Edinburgh

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I have seen unspeakable horrors

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Uncover the Secrets of Astrology With Pandit Prem Kumar Sharma, Astrologer in Edinburgh

Unlock the mysteries of the cosmos with Pandit Prem Kumar Sharma, a renowned Astrologer In Edinburgh. With his expert guidance and profound knowledge of the stars, Pandit Sharma can help you navigate life's challenges and opportunities with clarity and insight. Discover your true potential and uncover hidden talents through the ancient wisdom of astrology. Whether you're seeking answers about love, career, or personal growth, Pandit Sharma's personalized readings will provide you with valuable insights to guide your path forward.

0 notes

Note

What’s your prediction for the second slice of the shit sandwich?

Something involving the Waleses or Edinburghs. I lean towards it being the Waleses, since the Edinburghs were the second slice last time (the 2023 shit sandwhich, which confirmed Archie and Lili were using Prince/Princess titles) but since they're keeping lower profiles, it may be the Edinburghs again.

I think it may be one of these:

A new royal patronage for Kate from The King, probably something sentimental to Charles or one that used to be Her Late Majesty's. I'm on the fence about it being cancer-related...I feel like it could go artsy.

A declaration from Charles about William and Kate having authority to issue royal warrants. The right for the Prince of Wales to issue royal warrants isn't automatic. He has to be given permission by the monarch. It's assumed that William and Kate will someday be granted this ability, but Charles hasn't announced it yet. I do feel like maybe Charles would grant Anne that authority too, in recognition of her work as The Princess Royal (and that would actually be pretty big news).

Announcement of a state visit to UK in November and at the banquet, Kate, Anne, and Sophie have Charles's family order. The BRF traditionally receives a state visit in October or November each year. Since Charles is traveling in October, if there's a state visit in the autumn, it will probably be November. (November state visits are typically announced towards the end of September.)

A state thing happening while Charles is down under that requires the Counsellors of State, which William and Edward would do together because it can't be avoided or delayed till Charles returns. (If Counsellors of State are called while the monarch is away, they need two Counsellors to attend the matter.)

And it's very tinhatty (like 3%), but something involving a Sussex loss - maybe their titles get taken, maybe something with the bullying/staff reports, the lawsuits collapse, or some other kind of exposure that cancels them in a way we haven't seen yet. I don't usually give tarot and astrology a lot of weight, but when different readers in different circles on different platforms are seeing the same thing, I do consider that something to pay attention and right now, a lot of people are saying October/November looks very problematic for the Sussexes.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

indigovigilance meta index

blue marks my must-reads for meta theory, bold are recommended just for fun/feels/fanfaves

A Nightingale Sang in 1941 Maggie is Possessed Aziraphale, Nina, and Identity Miracles Don't Work Like That I’m honestly very glad that they went with two middle-aged men. Baraqiel and Azazel Lament of the Metatron The Erasure of Human!Metatron Jimbriel, Satan, the Book of Life, and what it means for Crowley Angel Pinky Rings Before the Beginning is Doctored Aziraphale Knew that Crowley was Living in his Car When They Became Their Own Side Falling Up: Jimbriel, Satan, the Book of Life, and what it means for Crowley pt2 Every single minisode is Aziraphale's memory, and why that's [not?] important It will be a line, but not between the two of them. Why Aziraphale Wears Reading Glasses Homoerotic Pistols at Dawn (a conversation with @queerfables) Tarot Symbolism in 1941 Why Crowley Rescues Aziraphale Honolulu Roast: the story of a coup One more note on Time Muriel is a Paralegal, and Crowley is going to need her help Aziraphale punches Jesus in the face

Sovereignty, Citizenship, and the Bookshop Why Crowley is "blind" to his Yellow Eyes Bildad the Shuite in Edinburgh Their Canon First Date Sodom and Gomorrah: A Speculative Meta Anthony, Anthony, Anthony The Final Fifteen is about Terry Pratchett's Death Neil Gaiman's 3 Cameos Mr. Brown Comforting Crowley Continuity Errors Book of Job - gamma-edit of @sensitivesiren Closeness They won't get married The Astrologer that Fell into a Well Why Crawley renames himself Crowley The Hornet in the Beehive The Child in S2E5 What's Up with Maggie Aziraphale, Kermit the Frog, and Fraggle Rock Season 2 Episode 6 ruined me Snake Vision Miraculous Energy Did God Forgive Aziraphale about the Sword? Restoring Angel!Crowley was Aziraraphale's Hope for 2,000 Years What Will Make Aziraphale Snap Aziraphale will go looking for people in Heaven Reusing the Cast Crowley's Dream Bullet Theory

You can also subscribe to my meta series on Ao3 to have new metas sent directly to your inbox, if you like.

~

General Post Index: contains links to others' meta and add'l resources

Support the community, read voraciously!

196 notes

·

View notes

Text

a quick "get to know the person behind the blog" while i write the 29th day of Kinktober fics (a later post, unfortunately)

nobody tagged me but anyway i found the trend very interesting and wanted to do it too <3 <3

Name/nickname: Vênus

Gender: Female

Star sign: Capricorn

Height: 5′2 (1.57)

Time: 09:21 pm

Birthday: 13, January

Favourite band: One Direction, Guns N' Roses, Bon Jovi, Fleetwood Mac

Favourite solo artist: Taylor Swift, Lana Del Rey, Ethel Cain

Song that’s stuck in my head: Sun Bleached Flies by Ethel Cain, Lilith by Saint Avangeline, Army Dreamers by Kate Bush

Last movie: The Substance and I also rewatched Me Before You for the 6th time

Last show: I was rewatching Hannibal (NBC) season 2 this week

When did I make this blog: March, I guess

What I post: Smut fics and Dark/Dead Dove Do Not Eat fics about s/o x female reader, but I'm gonna start writing angst sometimes and also s/o x female OCs and some specific random ships

Last thing I googled: The name of the actress who starred Possession (1981)

Do I get asks: YEAH! I love it when readers make requests, compliments or random comments. But unfortunately there's also a lot of anon hate

How did I chose my username: For those who believe in Astrology, some people say that our Rising Sign contains our Ruling Planet. My Rising is Taurus and Taurus is ruled by Venus. Venus is the "Roman version" of the Greek myth of Aphrodite, who is the Goddess of beauty, love, sex... and also she's one of my favorites. Besides Vênus is also my nickname. Anyway, "byline" would be because of the writing, I really don't know how to explain very well the thoughts I had that day hahaha

Following: 64 (I always forget to follow the accounts and I struggle afterwards trying to find the blogs 😭😭)

Followers: 1,122 (HOLY SHIT)

Average sleep: 3 or 4 hours probably

Lucky number: 7 and 13

Instruments: Unfortunately no one :(

What am I wearing rn: Black and red pajama shirt, black pajama pants and gray-pink socks decorated with pink and light blue candies

Dream trip: Anywhere in Scotland, but especially Edinburgh. London too

Favourite food: Strawberry

Nationality: Brazilian

Favourite song: All Too Well by Taylor Swift, that 10 minute version from Red (Taylor's Version)

Last book: I don't have time to read lately, but in October I reread The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

Top 3 fictional universes: A Song of Ice and Fire, Criminal Minds, Hannibal (but honorable mention for The Hunger Games)

Favourite colour: Dark Red (especially Maroon) and Pink (especially Amaranth Pink)

#venusbyline#get to know the person behind the blog#get to know the author#get to know me#get to know the blogger#about myself#about my blog#about me#fic writing#smut writer#smut scenarios#smut fanfiction#criminal minds smut#spencer reid smut#aemond targaryen smut#hotd smut#aegon targaryen smut#hotd scenarios#spencer reid x reader#aemond targaryen x reader#aegon targaryen x you#jacaerys velaryon x reader#jacaerys velaryon smut#smut headcanons#dead dove do not eat#dark smut#dark fanfiction#writer stuff#writers on tumblr#writeblr

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

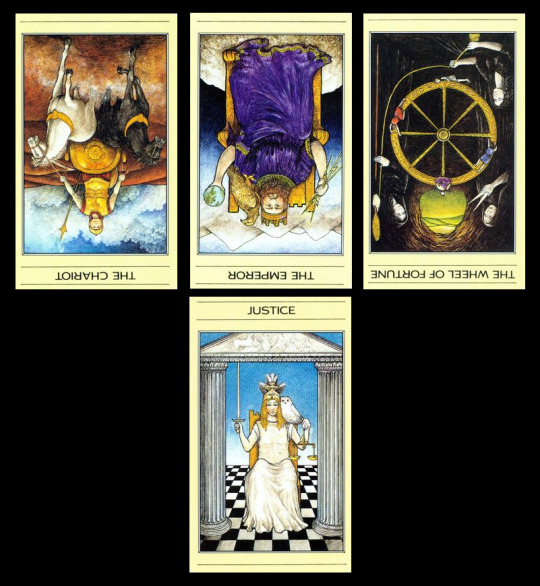

BRF Reading - 10th of March, 2023

This is speculation only

Cards drawn on the 10th of March, 2023

Question: How is Prince Edward's health? Is anything wrong? He looks terrible.

Interpretation: His health is in decline, caused in part by his brother the King.

Card One: The Chariot, reversed.

The Chariot is a card about going forwards. When it is in reversed you are stuck, you are blocked, you can't make progress. I asked about Prince Edward's health, so something is blocked, he can't make progress in some area.

The Chariot is the card of Cancer, ruled by the Moon. The Moon represents emotions and the mother, so Edward could be under a lot of emotional stress - not surprising seeing as he is still in the first year of grieving for his mother. He could be upset about not being given the Dukedom of Edinburgh, as that was his mother's last gift to him and it would be a comfort to receive it in his time of grief. More serious is the association with Cancer, which is an actual disease and one that killed his mother. I am hoping that this card is just about his grief and loss of his mother and his emotional stress - all very understandable.

Card Two: The Emperor, reversed.

The Emperor here is Charles, as he is the King. Something that Charles is doing or has done could be adding to Edward's grief over losing his mother (not giving Edward the Dukedom of Edinburgh is the obvious answer, but I feel that it is more - that is part of it but there are other things Charles has done or is doing that are adding to Edward's emotional stress).

The Emperor reversed is the bad leader - rigid, tyrannical, stubborn, only what I want counts - instead of being the wise, caring, protective father figure who looks after his family and his people. Some of Charles's actions are appearing to Edward to be on the nasty/tyrant side of leadership. I have the energy of no consultation happening, just the king issuing orders and expecting everyone else to go along with them. Edward has no power to defend himself or his family, and that is causing him great stress.

Astrologically, the Emperor represents Aries, the sign that is ruled by Mars and relates to the head in a medical sense. I would not be surprised if Edward is getting major stress headaches/migraines over how his brother is treating Edward and his family.

Card Three: The Wheel of Fortune, reversed.

This is a downward shift in fortune, wealth, and status. The Wheel of Fortune is the card of Jupiter, the planet of luck and expansion. reversed, it means no luck or luck taking a turn for the worse, and constriction rather than expansion. The energy of this card is of a decline in status. Prince Charles is going to reduce the status of Prince Edward and his children, and Edward is unable to stop this from happening, and it is causing him a great deal of stress.

In terms of health, this card means that Prince Edward's health is in the decline instead of getting better. He may not have reached the turning point in any health issues that he has.

Underlying Energy: Justice

This card is the only upright one in the reading. The energy of this card is of a plea for justice. Prince Edward wants justice, for himself and for his family. He wants balance - the energy of balance is coming through very strongly here. He wants the good deeds to be rewarded and the bad deeds to have consequences, and in his eyes the reverse is happening. He is tired and worn out and dealing with a deep grief for his mother, and he tries to fight for balance but he is not being given the opportunity to do so.

Major Arcana Cards:

The whole reading is major arcana cards, so this is important and public. Three of those cards are in reverse - that does not bode well for Prince Edward.

Conclusion:

Prince Edward is feeling the loss of his mother very strongly and is grieving for her. It is a constant emotional pain that does not go away and does not seem to ease over time. On top of this, he is dealing with a brother who he sees as acting like a tyrant, stripping his family of wealth and status and expecting them to go along with it simply because he (the brother) is King. There is no consultation, no 'what would you prefer', no options, just 'this is happening - deal with it'. This seems to be very unfair to Prince Edward when he contrasts this behaviour to how other family members are treated (e.g. Harry) - there is no balance in the situation. Prince Edward has no power to defend his family as it has been taken from him by his brother the King. All this is causing Edward a great deal of stress on top of his grief for his mother, and that is affecting his health in a serious way.

EDIT: I just looked up the medical astrology for the sign Cancer, and it rules the breast, chest and stomach, so Edward could be having stomach issues from the stress - maybe ulcers, maybe something else. That would fit in with his dramatic weight loss. Hopefully it is just the stress and grief affecting him and not something more serious.

87 notes

·

View notes

Note

how about george and mia ? do they have kids?

yesss they do! these don’t have faceclaims but let me introduce the two weasley girls, emilia and orion.

emilia weasley is a capricorn and like her mum, is obsessed with fashion. she’s sorted into gryffindor and once she starts her newts, she decides she wants to become a healer. she also loves astrology and campaigns to have it as an extra subject at newt level.

two years younger, there’s orion weasley.

orion’s a gemini hufflepuff and a bit of a social butterfly. she’s the seeker of her quidditch team and plans all of their parties after their wins, decorating the common room and making different themes. like her grandad, she loves muggle rock, and on weekends during her newts, she sneaks out of school to work in a muggle record shop in edinburgh (where she then goes to gigs and makes her secret group of muggle friends).

emilia’s fave song is girl almighty by one direction (it takes her a while to admit this) and orion’s is anything bowie.

ask me questions!

… or, ask me about my ships and their children!<3

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

15 QUESTIONS

I was tagged by the lovely @thebitchkingofangmar , @lotrlorien and @lordoftherazzles and even though i've done this a few weeks ago i'll do it again bc i don't want to be rude 😭💙

Are you named after someone? Yes my paternal grandma. Hara is a nickname of my full name though

When was the last time you cried? I can't remember tbh kfjsddkfs

Do you have kids? No and it will remain that way

What sports do you play/have played? Volleyball when i was young but now. literally nothing

Do you use sarcasm? Constantly, most of the time

What the first thing you notice about people? Their eyes and smile and also their "energy" or vibes

What's your eye colour? Dark brown

Scary movies or happy endings? Both is good tbh

Any talents? Good intuition, knowing when something is wrong, being able to remember names and dates and specific things that happened on those dates, also being able to find any article with free access (that's on being a librarian 💖)

Where were you born? Greece

What are your hobbies? Reading, listening to music, making new main blogs constantly (and then never using them), reading tarot, learning more about astrology and birth charts and just watching the same shows again and again

Do you have any pets? NO it's so sad.... I want two cats tho (one orange and one black / they are gonna be named mairon and melkor respectively)

How tall are you? 4'11

Favourite subject in school? History bc it was so easy to learn (im good at memorizing stuff)

Dream job? last time I said barista working in a cat cafe / bookstore (i still want that!!!) but now let's make it more specific. Librarian AND barista having a cat cafe / bookstore in Edinburgh and also working in an academic library during the morning hours and then going over to the bookstore !!!!!!. GAHHHH im yearning for this so bad

Gonna tag some of my new mutuals (no pressure tho!!!) : @sauronpilled , @swordwieldingeowyn , @ughtumno and @halfelven 🖤

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

https://www.tumblr.com/celticcrossanon/713603247038922752/brf-reading-4th-of-april-2023?source=share

This reading has left me with a very heavy feeling in the pit of my stomach. I understand that tarot readings are subject to change and up to interpretation, but in terms of consistency, this is the second reading where someone has said something to the effect of Kate being unwell at the coronation (you reblogged one a few days ago). The death energy is also seriously unsettling to me, especially if it has to do with a specific individual. They are not my personal family, but they do feel like it, and we have already had two deaths in the past two years. I don’t like to speculate on health matters, but Prince Edward has not looked well recently. You practice Vedic astrology - are your readings subject to change, or are they consistent over time? I would love for you to do a reading of the coronation now that we are closer in time to it. I like seeing different perspectives on this, and currently the energy from this reading has left me feeling dread.

I am really loathe to try and re-interpret someone else's reading, particularly since I am not a tarot reader.

I haven't studied Edward, The Duke of Edinburgh's chart, so I have nothing to say regarding him.

I think the problem is that the question asked is so open-ended.

If you can't admit that things in the BRF are going to change, then you'll always be confused about things.

Probably should ask more specific questions to get better answers, e.g. Will Beatrice & Eugenie lose their titles & styles? Because I'd bet that would get a clear yes. The coronation is likely their last hurrah as "royals."

Kate either has to attend or they have to announce a valid reason for her not attending. If she's going to be "sick," then they have to announce specifically what she is sick with. As in, if she has pre-eclampsia, then they're going to have to say that she has pre-eclampsia and that she's being treated for it, which is why she's not there. Being The Princess of Wales and missing the coronation at this day & age means you have to have a serious excuse, not just her die-hard stans wanting her to avoid being there.

#ask#tarot stuff#prince edward#princess beatrice#princess eugenie#operation golden orb#Catherine The Princess of Wales

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

for the astrology asks: sun, Sagittarius, 3H I hope you have a lovely day <333

hi, helloooo <3

sun ⇢ name 5 things you like about yourself?

answered here! i will not write more bc i'm having trouble thinking of more things asdjfhkdg

sagittarius ⇢ what places would you like to travel in the future?

i wanna revisit london, paris, prague and firenze like a true basic bitch, but as for places i've never been to before, i wanna go to edinburgh, verona, ROME (bitch has never been to rome can you imagine??), and some places in my own country that i've never been to before :))

3H ⇢ what are some of the topics you like to talk about the most?

if you don't know what to talk about with me, you can always prompt me to talk about my blorbos. after an hour of me explaining to you why i think larissa weems listens to siouxsie and the banshees, headcanons about jane murdstone's childhood, a long rant about how brienne of tarth is way too good for the likes of jaime, and an essay about why i think lucifer has a praise kink you will be like okay, i had enough of this bozo for at least a month :))))))

oh, or you can interest me in talking about women's mad scenes in media, stemming from greek tragedy, transitioning to opera and extending into film -- depends which mood you catch me in. it's either jan stevens having an egg kink or an hour-long rant and analysis of bulgakov's the master and margerita. good luck

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Consult the best astrologer in Cardiff if you want to know how dominant your zodiac sign is. Astrology has been a source of fascination and insight for hundreds of years. It offers a glimpse into the unique personal developments and characteristics related to each zodiac signal. While every character is unique, a few zodiac signs and symptoms tend to show off dominating traits more prominently than others.

#Best Astrologer in Cardiff#Best Astrologer in Glasgow#Astrologer In Edinburgh#Astrologer In Woolwich

0 notes

Text

Astrologer Vivek in Edinburgh provides expert readings to help you understand your life path. Get personalized guidance and find clarity with his astrology services. #astrologerinedinburgh #astrologervivek #edinburghhoroscope #astrologyadvice

0 notes

Text

Stonehenge's forgotten cousin 'of national importance' hidden on housing estate

Stonehenge in Wiltshire is famous as one of the world's most precious ancient monuments - a stone circle built thousands of years ago with a meaning yet to be fully understood by scholars. But the prehistoric site has a forgotten cousin that sits hundreds of miles away on a housing estate at the opposite end of the UK.

Jupiter (ritual) square Arrokoth (rituals that honor the sky (The monument is of national importance as an icon of prehistoric ritual, albeit in a modern urban setting)).

Originally built in the Neolithic period the stone was erected around 4,000 years ago, predating the Great Pyramid of Djoser which was the first in Egypt. But the single megalith can now be found next to a block of flats in a cul-de-sac on Ravenswood Avenue, Edinburgh.

The grey sandstone is nearly 7ft tall and is caged in by railings to protect it from vandals. Illustrations from the 19th century show the megalith standing alone in fields near Edinburgh.

It remained untouched until it was moved in the early 1800s to make way for road widening in the area. By the 1960s it was moved again as the new housing estate began to take shape, and it currently stands around 100 metres north of where it was originally.

Some say it was put in place to commemorate an ancient battle but a lot remains unknown about the badly weathered relic. It's one of several megaliths found dotted around the area - but the only one found on a housing estate.

The standing stone is a scheduled monument. A spokesman for Historic Environment Scotland said: "The monument is of national importance as an icon of prehistoric ritual, albeit in a modern urban setting.

"Although the stone no longer has any archaeological potential, it is a monument with cultural significance, capable of speaking to a modern urban population, and worthy of legal protection in its present setting."

Minor planet keywords developed by Philip Sedgwick, used with permission http://philipsedgwick.com/

Centaur, TNO & Asteroid Aspectarian http://serennu.com/astrology/aspectarians.php

0 notes

Text

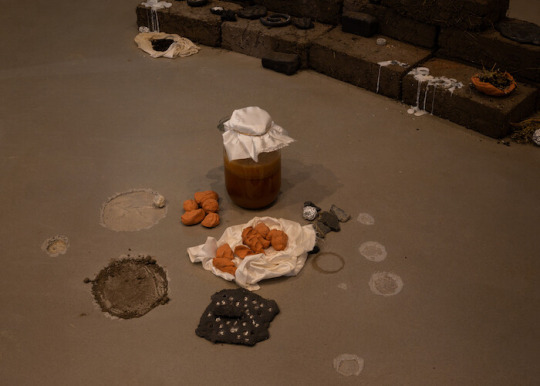

Wk 16, 4th of May, 2024 Artist Reference

Seshee Bopape: 〰️

ineo Seshee Bopape, "〰️ [when spirituality was a baby]”, mixed media installation, picture by Tom Jeffreys at Collective, 2018

From the text: Affirmation Arts presents PS: Parsing Spirituality by Micaela Giovannotti...

Affirmation Arts Gallery is pleased to present the most recent exhibition from international curator Micaela Giovannotti opening January 10th 2009. PS: Parsing Spirituality examines the recent resurgence of spirituality in contemporary art. Featuring artists: Janine Antoni, Sebastiaan Bremer, Melissa A. Calderon, Gordon Cheung, Graham Caldwell, Andrea Galvani, Dan Kopp, Ivan Navarro, Lisa Ross, Courtney Smith, Xaviera Simmons, and J. G. Zimmerman.

“Every work of art is the child of its age and, in many cases, the mother of our emotions” (Concerning the Spiritual in Art, W. Kandinsky.)

After being neglected for quite some time, spirituality has risen to the surface in contemporary art. Spirituality based on religious belief has been part of art history since the dawn of time. Art has both advertised and glorified religions, but contemporary art has generally distanced itself from the spiritual realm, focusing its lens on formal and conceptual tenets. Not surprisingly, as often happens in times of secular uncertainties and political and economic turmoil, there is currently a resurgence of interest in spirituality, wherein artists are exploring and re-defining themselves in their work with very introspective and personal means and approaches. However, from a different perspective, these new spiritual elements can be interpreted in part as a contemplative reaction. Layered with complexity, these explorations include universal issues that, while external, are nonetheless of primal importance to the self.

access here:

From the text: Dineo Seshee Bopape's "〰️ [when spirituality was a baby]” by Tom Jeffreys...

Dineo Seshee Bopape, "〰️ [when spirituality was a baby]”, mixed media installation, picture by Tom Jeffreys at Collective, 2018

At once named and unnamable, Dineo Seshee Bopape’s installation 〰️ gathers myriad references (astrology, classical sculpture, Afrodiasporic spiritual practices, the Anthropocene) and materials (soil and rocks, satin and spices, glass and plastic, charcoal, jute, feathers, clay). It weaves them together thrillingly, with gold wire, cotton thread, and lines scraped into the concrete floor. In scale, the installation oscillates from tiny holes made by drawing pins to the vastness of a universe. Seen as a single entity, this is a work that marks itself, maps itself, archives its own making and its own meanings. It is a work that prompts a pile-up of words and renders them all inadequate. All my notes are lists.

The first mystery of the exhibition is its title: a glyph designed by the artist consisting of six wavy vertical marks, represented here by the “〰️” symbol. In print it is like rising steam (or is it falling rain?). Scratched into the gallery floor, or marked in tiny biro lines on the wall, these wobbly lines read more like the Egyptian hieroglyph for water: a linguistic echo of tidal marks in sand or the flowing of a river. It does not translate into letters or sound or language; it cannot be converted into Unicode. In square brackets is a clue: [when spirituality was a baby]. This phrase reaches back toward a nascent state before belief had crystallized into institutional religions, before land ownership perhaps, before meaning itself had yet solidified.

Like many of Bopape’s expansive sculptural installations, 〰️ is almost overwhelming. There are so many things and so little space for the visitor. The octagonal City Dome, one of the buildings of the recently renovated former observatory atop Edinburgh’s Calton Hill, is not big. But the installation contains such an array of materials that they are listed on an accompanying paper: 57 of them, in alphabetical order. These materials span the globe. Bopape has brought soil from the Congo, Germany, Iceland, Palestine, and South Africa. There is citrine from Brazil and verbena from Ukraine. Deep time and a shallow present lie side by side: mammoth bones and charcoal, 225-million-year-old wood from Madagascar alongside tinfoil and plastic bottles.

It feels at first like a place of ritual: there are candles, semi-precious stones, and the smell of incense. Bopape has made dozens of clay shapes, some like tiles, others formed by the clenching of a fist. Snowy owl feathers are tied to bowed branches that hang on golden thread from the high domed roof. And, befitting of an installation that took nine months to birth, there is also life: jars of kombucha.

This is a vital clue. What is a constellation but a series of lines imposed on a world to make it mean something? A constellation is a silhouette, a gathering, a metaphor, knowledge itself—the layout of Bopape’s entire installation mirrors the stars of Canis Major. Perhaps, after all, this is less about all these material objects than about the wavy lines that connect them—sound, light, language, history, truth—and who has had the power to draw them. Everything here is imbued with meaning. It seeps out across the floor, into the air, and suddenly there is no empty space: not a void between objects, but a breathy and unmappable tapestry of infinite affinities.

This work in that way links to my 'like a constellation of marks' installation strategy. Inferencing many ritual means (artefacts, domesticated nature, fairy rings, grove lines) the works coalesce in a series of marks on the floor space. Connected by histories, their find spots, place and shape, these floor arrangements speak of connected sources.

Left: Ashley Singer, Installation strategy in DEMO Gallery 1, 2024, greenware porcelain, space size approx 1M by 5M

Right: Ashley Singer, Installation strategy in DEMO Gallery 2, 2024, greenware porcelain, space size approx 8M by 5M

0 notes

Text

Introduction to Teersa

Note: Here is the final part of my OC introduction series! Please enjoy reading and reblog them if you want to or not. It will be on my masterlist here.

「 𝐁𝐀𝐒𝐈𝐂𝐒 」

Full name: Teersa Lumera Prisvielle

Species: Xelhua (Hybrid of Light Fae and Dark Fae)

Gender: Female

Age: 700 years of age

Date of Birth: November 5th

Astrological Sign: Scorpio

Birthplace: Magical forest land of the Fae

Height: 5'2 (157.48 cm)

First residence: Magical forest land of the Fae

Current location: Iridia in Edinburgh, Scotland

Occupation/Profession: Leader of the Fae (formerly), Taste tester

Companion: Rose (Snake)

Personality Traits

• Mischievous

• Self-Confident

• Compassionate

• Empathic

• Dedicated

• Mindful

Abilities/Skills

• Precognition

• Flight

• Shapeshifting

• Glamour

• Speaking any language at will

• Telepathy

• Immortality

• Portal Creation

• Photokinesis

"I’m still in a long dream. A dream I couldn’t tell anyone about"

Teersa Tudor was born as a Xelhua, a Hybrid of light and dark Fae. At first, she wasn't normally accepted in the land of the Fae, but the Elders managed her to remain there until adult age. It took time for accept the idea and they moved on like nothing happened.

As she gotten older, her dedication and hardwork caught the eyes of many, including the Elder himself. One day, he offered her to replace him as leader through the land. She genuinely accepted for the role and dedicated herself to be one for the sake of the land. Everything turned out well until major false accusations thrown at her. In order to not making it worse, she took a major decision to step down the role and left everything behind. It was the most difficult decision she ever made.

In the Present, Teersa resides in a normal life in the peaceful land of Iridia where her family founded. It gave an opportunity as a taste tester for the culinary team in the lands. Everything has been going well for her until the past was slowly catching up to her and she managed to face it somehow. Everything was on the line upon the dangerous situation, including her own life.

Who knows what will occur in the story of the redheaded Xelhua herself?

#Teersa Prisvielle#Fae Hybrid#character introduction#original writing#writing#creative writing#original content#content writer#original character#content writing

1 note

·

View note

Text

Astrology: Prince Philip's natal chart. 'You bloody what?! Astrology? Codswallop!'

Well we're going there, curtesy of the brilliant @philibet-fandom

A Gemini: Inquisitive, multi-talented, multi-enthusiast. If he didn't know about the subject then he'd certainly try & find out about it!

& A Leo moon: (Just like his Wife Elizabeth🌙) big hearted, fiercely loving & emotionally protective, emanates jovialness, proud. Oh & did i mention the sign of Royalty.👑

Sun in 5th house: Fatherhood was his joy, as we're hobbies, creativity, learning new skills & being child-like about it. The Duke of Edinburgh awards comes to mind here, seeing the benefit of learning from nature, experiences through adventure & not only that but how it exploration can form a sense of self (Sun).

Gemini Mars: Thrived on movement, change, variety. Action brought thinking, thinking brought passion! & Anger could be channelled via sport.🏇

Dominant in Earth element & Mutable mode, making him more Virgo than his star-sign Gemini: reliable, practical, honest, dedicated, hard-working, disciplined, smart, no messing about, cleaning up everyone else's mess. (His daughter, Anne has this too.)

Pluto in the 6th house: Service to others ran deep, sacrifice in his life transformed the bloke. They we're Death & Re-birth moments. I guess, this point shows his service to the crown, his wife, his country. Literally one life to another one. Pluto was his 10th house ruler aptly too (10th = vocation) his career was revolutionary.

Jupiter opposite Uranus: Peculiar beliefs👽. Creative brilliance. Ingenuity in modernizing old customs & unorthodox ways refreshing rigid establishments. Compelled to make change!

2nd, 3rd quadrant heavy: interested in & cared more about others than himself. In fact all his personal planets (mercury, moon, mars, sun, are all on that side!) Devote their ALL to people, he came second. Emphasized by his Mercury bang on his descendant line. Loved to pick peoples brains & was mentally stimulated by conversation, 1 on 1 relationships. & All in Cancer: cared a lot, also temperamental.

Saturn in 8th house: longevity. (Yep.)

OOB Mercury: A can't be boxed type of intelligence.

Taurus IC: Stubborn to the core, once he made up his mind, good luck convincing him otherwise, but loyal as they come. Foodies also.

Venus on the IC: This guys love was roots on a tree💗, it's what sustained him & was the food to his success. Love for his family & those who felt like enriched him. The peace keeper & maker of the house, Venus ruling harmony too. Venus on IC types have deep affection with the Arts, love to put their stamp on their property (Overseeing Windsor castles post-fire renovations & interiors of the Yacht Britannia, is very fitting here.)

Mercury square Chiron: challenges with siblings.

Sedna conjunct Chiron: The man knew trauma. Sedna involves pain/loss/grief/abandonment with male figures in particular, combine that with Chiron= wounding/wisdom. Whilst some remain stuck in their darkness, other with this can transform the wound into wisdom (Chiron) & in-turn food for others (Sedna).

9th house ruler in 4th house: like to bring back other cultural customs to their home-life.....even ornamental 1's, say? A wine-bottle Grasshopper cooler 🦗 (you know the story?) 😉

Jupiter in Virgo 8th house: Blunt sense of humour, occasionally dark. & As it was in the 8th along with Saturn, his humour, honesty, philosophies on life, sacrifice, stoic nature & dedication became his legacies.

Makemake conjunct Sun: climate/environmental wisdom, nature & conservation played great importance.

Fixed star Vega conjunct Ascendant: handsome, loveable, refined, statesman, successful influential figures. (I mean, am i saying anything new here?!)

Juno conjunct Ascendant: now this is my favourite. Juno epitomizes consort, dedication & loyalty. & As ascendant is our outward persona. Well, it's what we knew him for most.

Post-note: on the day of his Thanksgiving service, 29th of March 2022: *Asteroid Memoria (clues in the name) conjuncts Philip's Natal South node: his past. *Asteroid Philip conjuncts his Moon: emotions. *& Asteroid Queen conjunct's his natal Juno (the consort point.) ..................Can you get more fitting?

*photo- my photoshop edit.

57 notes

·

View notes