#Archaeological Museum of Argos

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A figure holding two tridents stands between horses. The scene has been interpreted as ritual horse-sacrifice, though this is not certain. Ancient Greek pottery fragment in the Geometric style, dating to the Archaic period (8th century BCE) and located in the Archaeological Museum of Argos. Photo credit: Zde/Wikimedia Commons.

#classics#tagamemnon#Ancient Greece#Archaic Greece#art#art history#ancient art#Greek art#Ancient Greek art#Archaic Greek art#Geometric period#pottery#potsherd#Greek religion#Ancient Greek religion#Hellenic polytheism#vase painting#Archaeological Museum of Argos

236 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edward Coley Burne-Jones, 1833-1898

Danäe and the Brazen Tower, 1872, oil on panel, 38x19 cm

The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology (Oxford, UK), Inv. WA1948.32

Burne-Jones probably used William Morris's 'Earthly Paradise' as the source of this subject. Acrisius, King of Argos, having been warned by the oracle that he would be killed by his daughter's son, imprisoned her in a tower of brass. This is one of two small versions of the subject painted by Burne-Jones for one of his strongest supporters, the Glasgow merchant, William Graham, in 1872; the second version, of 1876, is in the Fogg Art Museum. Burne-Jones's definitive treatment of the theme (Glasgow Museum and Art Gallery), was exhibited in 1888.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Riace Bronzes: Masterpieces of Ancient Greek Art

The Riace Bronzes, two stunningly preserved ancient Greek statues, are among the greatest archaeological discoveries of the 20th century. Found off the coast of Riace, Italy, in 1972, these life-sized bronze warriors date back to around 460–450 BCE, during the height of the Classical Greek period. The bronzes are celebrated for their realism, intricate detail, and the insight they provide into the artistic achievements of ancient Greece.

Discovery

In August 1972, a scuba diver named Stefano Mariottini stumbled upon the statues while diving near the town of Riace, Calabria, in southern Italy. Initially mistaking one for a corpse, Mariottini soon realized he had found something extraordinary. The bronzes were recovered from the seabed at a depth of about 8 meters (26 feet). Their nearly pristine condition sparked immediate fascination among archaeologists and art historians.

The statues were transported to Florence for extensive restoration before being displayed to the public. Today, they reside in the National Archaeological Museum of Reggio Calabria, where they continue to attract visitors from around the world.

Description of the Statues

The Riace Bronzes consist of two male figures, referred to as Bronze A and Bronze B. Though similar in many ways, they exhibit distinct characteristics:

Bronze A

• Depicts a young, athletic warrior with an idealized muscular physique.

• Stands approximately 2 meters (6.5 feet) tall.

• Features curly hair and a beard, crafted with intricate detail.

• Likely held a weapon (such as a spear) in one hand and a shield in the other, though these elements have been lost.

Bronze B

• Represents an older, more seasoned warrior, with a slightly different posture and facial expression.

• Also stands close to 2 meters tall but appears more robust and less lithe than Bronze A.

• Shows more pronounced veins and wrinkles, highlighting the artist’s attention to realism.

Both statues were created using the lost-wax casting method, a sophisticated technique that allowed ancient artists to achieve incredible detail and precision.

Artistic and Cultural Significance

The Riace Bronzes exemplify the transition from the Archaic to the Classical period in Greek art, showcasing a blend of idealism and realism. Key features include:

• Dynamic Poses: Unlike the rigid, frontal stance of earlier Archaic statues, the bronzes exhibit a contrapposto pose, with weight shifted onto one leg, creating a sense of movement and naturalism.

• Detailed Anatomy: The musculature, veins, and facial features are rendered with incredible precision, reflecting the Greek ideal of physical perfection.

• Expression and Character: Each figure conveys a distinct personality, highlighting the increasing focus on individuality in Classical art.

The bronzes may have been part of a larger group of statues, possibly depicting a mythological or historical scene.

Origin and Purpose

The exact origin and purpose of the Riace Bronzes remain a mystery. Scholars suggest they were created in a Greek city-state such as Athens or Argos and transported across the Mediterranean. Their intended use could have been:

• Dedications to the Gods: Statues like these were often placed in temples or sanctuaries as offerings to deities.

• Commemorative Monuments: They may have been created to honor warriors or heroes, either mythological or historical.

• Decorative Elements: Some scholars speculate they adorned a public space or private estate.

The statues likely ended up in the sea during a shipwreck while being transported, possibly to Rome, where Greek art was highly prized.

Restoration and Preservation

When the Riace Bronzes were recovered, they were encrusted with marine sediment and partially corroded after centuries underwater. Restoration efforts included:

• Removal of marine deposits and stabilization of the bronze.

• Reconstruction of missing parts, such as the eyes, which were originally inlaid with ivory and stone.

The bronzes’ exceptional condition is attributed to their burial in sandy seabed conditions that protected them from extensive damage.

Legacy

The Riace Bronzes are considered masterpieces of ancient Greek art and provide invaluable insight into the technical and artistic achievements of the Classical period. Their discovery reignited interest in Greek sculpture and reminded the world of the enduring beauty and sophistication of ancient art.

Today, they are a symbol of Calabria’s cultural heritage and a testament to the enduring legacy of Greek civilization.

Fun Facts

1. The Mystery of Their Identity: The figures may represent mythical heroes such as Achilles, Heracles, or Tydeus, though their exact identities remain unknown.

2. Perfect Proportions: The bronzes follow the Greek “canon of proportions,” emphasizing harmony and balance in the human form.

3. A Global Attraction: The Riace Bronzes draw thousands of visitors annually and are a centerpiece of the National Archaeological Museum of Reggio Calabria.

The Riace Bronzes continue to captivate scholars and art lovers alike. Their discovery not only deepened our understanding of ancient Greek sculpture but also reminded us of the enduring power of art to transcend time. What do you find most fascinating about the Riace Bronzes? Let’s discuss!

0 notes

Text

Hera, has been depicted on various coins throughout history, especially in regions where her worship was prominent. Here are some key aspects:

1. Greek Coins:

- Argos: Hera was particularly revered in #Argos , and coins from this region often depicted her. These coins might feature her likeness or symbols associated with her, such as a peacock.

- Samos: As Hera was the patron goddess of #Samos , coins from this island sometimes bear her image or symbols.

2. Roman Coins:

- During the Roman period, Hera was syncretized with Juno, her Roman counterpart. Roman coins sometimes feature #Juno with attributes similar to those of Hera, such as the peacock or a diadem.

3. Iconography:

- #Hera is typically portrayed as a majestic, mature woman, often wearing a crown or diadem.

- Symbols associated with her include the peacock, a scepter, and a pomegranate.

These depictions on coins served not only a religious purpose but also a political one, emphasizing the city’s connection to divine favor and authority. #archaeology #ancient #ancienthistory #museum #numismatics #numismatist #numismatica #rarecoins #oldcoins #worldcoins

#coincollecting #coincollection #gold #metaldetecting #silvercoins

#coin #romancoin #ancientcoins #ancientgreekcoins #money #history.

#temple#art #greece #alsadeekalsadouk #الصديق_الصدوق

0 notes

Photo

Polycleitos (Argos, 5th c BC)

_

Diadumenos (diadem-bearer) / Youth Tying a Headband. The Athens example, copy of bronze original ca. 420 BC. Marble: 1.95 m H. National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

Winner of an athletic contest, lifting his arms to knot the diadem. The figure stands in contrapposto. “The thorax and pelvis of the Diadumenos tilt in opposite directions, setting up rhythmic contrasts in the torso that create an impression of organic vitality. The position of the feet poised between standing and walking give a sense of potential movement. This rigorously calculated pose, found in almost all works attributed to Polykleitos, became a standard formula used in Greco-Roman and, later, western European art."

Doryphoros (spear-bearer). Rendered somewhat above life-size: 2.12 m (6 feet 11 inches), the lost bronze original of the work would have been cast circa 440 BC, but it is today known only from later (mainly Roman period) marble copies.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Doryphoros.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doryphoros

Polykleitos - Alchetron, The Free Social Encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diadumenos

Photographs of the first excavations at Delos island, where both sculptures were unearthed. From the 19th c. French archaeologists book “Delos 1873-1913″.https://greekreporter.com/2022/05/13/excavations-greek-island-delos/

Kararadaygum Photography: Diadumenos portrait (top)

https://kararadaygum.tumblr.com/post/672887937879408640

https://kararadaygum.tumblr.com/

thnx didoofcarthage & ancientprettythings

#Polycleitos#sculpture#Diadumenos#Doryphoros#archaeology#Delos#gr#copy#marble#beauty#male#classic#contrapposto

516 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aphrodite Areia, 1st C. CE copy of 400 BCE statue by the school of Polykleitos, possibly Polykleitos the Younger. National Archaeological Museum in Athens (see NAMA 262).

"The Temple of Aphrodite Kytherea was a sanctuary in ancient Kythira dedicated to the Goddess Aphrodite. It was famous for reportedly being the eldest temple of Aphrodite in Greece. It was dedicated to the Goddess under her name and aspect as Aphrodite Ourania and contained a statue of an Armed Aphrodite. The temple is dated to the 6th century BCE. While considered a significant sanctuary, it was described as a small building.

According to Hesiod, Kythira was the first island that Aphrodite passed as she rose from the sea.

Herodotus (Histories 1.105.3) described it:

"This temple, I discover from making inquiry, is the oldest of all the temples of the Goddess, for the temple in Cyprus was founded from it, as the Cyprians themselves say; and the temple on Cythera was founded by Phoenicians from this same land of Syria."

Pausanias (Description of Greece, 3.23.1 & 1.14.7) also said of it:

"In Kythera [off the coast of Lakedaimonia] is . . . the sanctuary of Aphrodite Ourania (the Heavenly) is most holy, and it is the most ancient of all the sanctuaries of Aphrodite among the Greeks. The Goddess herself is represented by an armed image of wood. This is the only temple I know that has an upper storey built upon it.

...a sanctuary of the Heavenly Aphrodite; the first men to establish her cult were the Assyrians, after the Assyrians the Paphians of Cyprus and the Phoenicians who live at Ascalon in Palestine; the Phoenicians taught her worship to the people of Cythera."

Aphrodite Areia (Ancient Greek: Ἀφροδίτη Ἀρεία) or "Aphrodite the Warlike" was a cult epithet of the Greek Goddess Aphrodite, in which she was depicted in full armor like the war God Ares. This representation was found in Sparta and Taras (modern Taranto). There were other, similarly martial interpretations of the Goddess, such as at her Sanctuary at Kythira, where she was worshiped under the epithet Aphrodite Urania, who was also represented as being armed. The epithet "Areia", meaning "warlike", was applied to other Gods in addition to Aphrodite, such as Athena, Zeus, and possibly Hermes.

The association with warfare contradicts Aphrodite's more popularly known role as the Goddess of desire, fertility, and beauty. In the Iliad, Aphrodite is portrayed as incompetent in battle, being wounded in the wrist by Diomedes under the guidance of Athena, and she is reminded of her role as a love Goddess rather than a war Goddess like Athena by Zeus. It is possible, however, that this representation was deliberate to assert the Ionian interpretation of Aphrodite, which did not portray the Goddess with warlike aspects, as the "correct" version.

It is believed that the warlike depiction of Aphrodite belongs to her very earliest acolytes and cults in Cyprus and Cythera, where there was a strong eastern influence during the Orientalizing Period. This depiction can trace Aphrodite's descent from older Middle Eastern Goddesses such as the Sumerian Inanna, Mesopotamian Ishtar, and Phoenician Astarte. In Cyprus, Aphrodite was also referred to by the epithet "Aphrodite Encheios" (Aphrodite with a spear), and it has been suggested that the cult was brought from Cyprus to Sparta. She was also known by this name on the Areopagus and at Corinth.

There were cults dedicated to the warlike aspect of Aphrodite in Kythira, Cyprus, Argos, Taras and most prominently in Sparta.

Pausanias recorded that three cult statues at Kythira, Sparta, and Corinth depicted Aphrodite as holding weapons and archeological evidence points to this portrayal also occurring in Argos. Pausanias' claim that "Aphrodite Areia" was simply a female version of Ares has some support in the contemporary epigraphy.

In Sparta, Pausanias described two temples dedicated to Aphrodite Areia and archeological evidence supports this claim. Various authors make reference to Sparta worshipping an armoured Aphrodite, such as Plutarch, Nonnos, and Quintilian. Pausanias' claim that "Aphrodite Areia" was simply a female version of Ares has some support in the contemporary epigraphy. A related Spartan epithet, "Armed Aphrodite" (Ἀφροδίτη 'Ενόπλιος) was associated with an etiological myth recorded by Lactanius, who stated that once the Spartan army was away from the city attacking Messene, part of the Messene army launched a counterattack against Sparta that was thwarted by the Spartan women who armed themselves and defended the city. The Spartan army, realizing their city was under siege, returned and assumed that the women were the enemy army until they stripped off their armour to reveal their identities. It is likely that this myth was used to explain the origin of an unknown Spartan festival that functioned similarly to the Argive festival of Hybristica, where women took over the roles of men.

In Argos, Aphrodite Areia appears to be related to Nikephoros ("victory bearer") and in a nearby city of Manteneia, there was a temple devoted to both Aphrodite and Ares."

-taken from wikipedia

#aphrodite#venus#ancient greece#pagan#paganism#european art#antiquities#sculpture#literature#history#statue#art#museums

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

Untangling Blackness in Greek Antiquity

Sarah F. Debrew Untangling Blackness in Greek Antiquity, Cambridge University Press 2022

How should articulations of blackness from the fifth century BCE to the twenty-first century be properly read and interpreted? This important and timely new book is the first concerted treatment of black skin color in the Greek literature and visual culture of antiquity. In charting representations in the Hellenic world of black Egyptians, Aithiopians, Indians, and Greeks, Sarah Derbew dexterously disentangles the complex and varied ways in which blackness has been co-produced by ancient authors and artists; their readers, audiences, and viewers; and contemporary scholars. Exploring the precarious hold that race has on skin coloration, the author uncovers the many silences, suppressions, and misappropriations of blackness within modern studies of Greek antiquity. Shaped by performance studies and critical race theory alike, her book maps out an authoritative archaeology of blackness that reappraises its significance. It offers a committedly anti-racist approach to depictions of black people while rejecting simplistic conflations or explanations.

Chapter 1 - Introduction

The Metatheater of Blackness

Summary

Chapter 1 situates the reader within the landscape of Blackness in the twenty-first century. In addition to laying out the task at hand (untangling representations of blackness in Greek antiquity), this chapter underlines the dangerous consequences that occur when scholars conflate modern tropes with ancient material.

Chapter 2 - Masks of Blackness

Reading the Iconography of Black People in Ancient Greece

Summary

Chapter 2 offers a visual paradigm for representations of black people in the ancient Greek world. It considers fifth-century BCE janiform cups that depict black and brown faces on opposite sides. Contemporary ideas are all the more pronounced when dealing with visual constructs of skin color in Greek antiquity and therefore require continual interrogation. Disputing the uncomfortable ease with which some art historians presume a fixed connection between black people and bumbling inferiority, this chapter argues that the black face serves as part of a repertoire of sympotic performance. Similar to masks, janiform cups enable drinkers in the symposium to adopt new identities. The discourse about the chromatics on janiform cups leads to a broader examination of black skin in ancient Greek art. Close scrutiny of museum displays reveals the temporal clash that can occur when audiences encounter iconography of black people in Greek antiquity. In particular, scrupulous inspection of the British Museum unearths a troubling tendency to privilege ancient Egypt as an indication of legitimacy and legibility, contrasted with Nubia.

Chapter 3 - Masks of Difference in Aeschylus’s Suppliants

Summary

Chapter 3 dissects the role of black skin color in Aeschylus’s Suppliants (c. 463 BCE). In this tragedy, Danaus’s black daughters, the Danaids, flee from Egypt to Argos to escape a forced marriage to their Egyptian cousins. Their knowledge of Greek religious rites convinces the Argive ruler, Pelasgus, that they are distant kin even though this Greek identity is seemingly contradicted by their black skin. This chapter asserts that the Danaids are sophisticated performers who successfully reduce the relevance of their physical alterity and declare their hybrid identity as black Egyptian Greeks. They are versatile and subtle ethnographers of the Argive Greeks to whom they supplicate. Conversely, their Argive audience – the intra-dramatic spectators of the Danaids’ difference – prove less able to comprehend their hybridized identity. An exploration of political resonances, particularly in relation to metics, draws the fifth-century BCE audience away from the distant mythical realm and towards their own political reality. Altogether, the drama speaks to the complicated exteriority of race in an ancient Greek tragedy.

Chapter 4 - Beyond Blackness

Reorienting Greek Geography

Summary

Chapter 4 delves into accounts of meetings between the mighty Aithiopians and their distant neighbors. Herodotus’s iteration of Aithiopia (Hdt. 3.17–26) simultaneously looks back to Homer’s utopian Aithiopia and positions Aithiopia as a historical allegory to critique Athenian imperial aggression. Through the Aithiopian king’s comments to Egyptian spies, Herodotus undermines any fixed, negative assumptions of foreigners that may lurk among his readership. Moreover, Herodotus distinguishes Aithiopians by their height, longevity, and skin color, thereby complicating a facile rendering of black people’s “race.” A reciprocal ethnography of Scythians further exposes the instability of race as two Scythian men, Anacharsis and Scyles, wear Greek clothes and maintain their Scythian identity (Hdt. 4.76–80). Their untimely demise reveals the dangers that Hellenocentric Scythians face once they return to their xenophobic homeland.

Chapter 5 - From Greek Scythians to Black Greeks

A Spectrum of Foreignness in Lucian’s Satires

Summary

In Chapter 5, Lucian (c. second century CE) presents a complicated model of difference that relies unevenly on skin color, attire, and language as determinants of identity. His trio of Scythian satires features characters who rework the relationships between race and identity within their specific contexts. The categories of “Greek” and “foreigner” become muddled as Greeks and Scythians share their impressions about black people in their midst: Greeks conflate blackness with Aithiopians or liken it to their own appearance with ease, while one Scythian man marvels at the sight of black Athenian athletes. These varied observations lead to a collective questioning of blackness in relation to Greek identity under the guise of humor.

Chapter 6 - Black Disguises in an Aithiopian Novel

Summary

Chapter 6 continues to upend the limiting Greek–foreigner binary model. Heliodorus’s novel Aithiopika (c. fourth century CE) traces the peripatetic journey of Charicleia, an Aithiopian princess exposed at birth because of the dissonance between her white skin and her parents’ black skin. During Charicleia’s travels, skin color remains a volatile element: she exploits it as a disguise (Heliod. Aeth. 6.11.3–4), her companion Theagenes uses skin color as a marker of trustworthiness (7.7.6–7), and a prophecy destabilizes both perspectives (2.35.5). Throughout the novel, Heliodorus wields skin color as a negotiable ethnographic tool that does not necessarily correspond to identity. This flexibility underscores Charicleia’s own fluidity between several performative categories. She can be a beggar and a princess, a docile woman and the leader of her entourage, the daughter of a Greek man and an Aithiopian man. Readers are forced to be patient as Heliodorus masterfully manipulates time to create a gap between what his characters know and what his readers have already grasped.

Chapter 7 - Conclusion

(Re)placing Blackness in Greek Antiquity

Summary

Chapter 7 concludes by reiterating the invisible ontologies that haunt current assessments of black skin. The fluid construction of black skin in ancient Greek literature and art aims to confront limiting treatment of race in the modern academy. A final glimpse at the poetry of Langston Hughes (1931) and Gwendolyn Brooks (1980) offers a suggestive model for revamping the ancient Greek archive in the twenty-first century.

Source: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/untangling-blackness-in-greek-antiquity/conclusion/EB4894DB8B804EAFBE08F774C3C0D31F

Sarah Derbew, Assistant Professor of Classics, School of Humanities and Sciences, Department of Classics, Stanford University

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

: • I PITTORI DI POMPEI Exhibition 'Mobile' Overview II.: "The Painters of Pompeii" 23/09/22-19/03/23 at Museo Civico Archeologico di Bologna | MCAB http://www.museibologna.it/archeologicoen @bolognamusei [Frescoes from MANN @museoarcheologiconapoli] . Sunday 05|02|2023 Phone cam quick snaps | brief 'mobile' overview ["I Pittori di Pompei" only]: . 👉 PART 2 . • Pics 1-2: Heracles and Omphale From Pompeii IX, House of Marcus Lucretius [Triclinium, East wall, Central section] 1 AD, Fourth Style Pic 1 : Omphale, Detail. [MANN] . • 3-4: Heracles and Omphale [Drunken Heracles] Pompeii VII, Insula Occidentalis House of the Prince of Montenegro [Oecus, Central section] 1 AD, Third Style 14 : Omphale, Detail. [MANN] . • 5: "Xenia" Room Fourth Style Wall with Still Lives Pompeii II, Praedia Lulia Felix [Tablinum, South wall] 1 AD. [MANN] . • 6: Venus and Mars | Detail Pompeii VII, House of Punished Love [Tablinum, South wall, Central section] 1 AD, Third Style. [MANN] . • 7: Europa on Bull | Detail Pompeii IX, House of Jason [Cubiculum, West wall, Central section] 1 AD, Third Style. [MANN] . • 8: Polychrome Stucco with Drunken Heracles Pompeii VI, House of Meleager [Tablinum, North wall, Upper register] 1 AD, Fourth Style. [MANN] . • 9-10: Io and Argo Pompeii VI, House of Meleager [Tablinum, North wall, Central section] 1 AD, Fourth Style 10 : Io, Detail. [MANN] . MCAB | MSP 05|02|2023 'Mobile' Overview Part II. The photographed objects is the property of MANN | MCAB and subject to the Museum[s] copyright. Sorry for the watermarks. [4 more pics on my FB]. . . #bologna #museocivicoarcheologicobologna #bolognamusei #archaeologicalmuseum #museoarcheologico #historymuseum #ipittoridipompei #thepaintersofpompeii #mann #pompei #pompeii #herculaneum #ancientpompeii #fresco #frescoes #exhibition #romanart #ancientart #arthistory #ancient #antiquity #archaeology #mythology #museology #heritage #archaeologyart #ancientworld #museumphotography #archaeologyphotography #michaelsvetbird @michael_sverbird ©msp @bolognamusei @museoarcheologiconapoli | bologna 05|02|2023 i pittori di pompei mobile overview part II. (at Museo Civico Archeologico di Bologna) https://www.instagram.com/p/Coffd4zoZsL/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#bologna#museocivicoarcheologicobologna#bolognamusei#archaeologicalmuseum#museoarcheologico#historymuseum#ipittoridipompei#thepaintersofpompeii#mann#pompei#pompeii#herculaneum#ancientpompeii#fresco#frescoes#exhibition#romanart#ancientart#arthistory#ancient#antiquity#archaeology#mythology#museology#heritage#archaeologyart#ancientworld#museumphotography#archaeologyphotography#michaelsvetbird

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Which places (famous and not so famous) do you recommend to visit in Greece to experience what is the Greek culture

Thank you

Hello, friend! The answer is easy in theory but hard to execute: pretty much everywhere! You might be downsizing Greece in your mind, especially if you ask non famous places too. First of all, it depends on what you mean by Greek culture: some regions had glorious days in antiquity, some reached power in the Byzantine and medieval times and others played a key role in Modern Greek history (i.e Greek revolution). Many of them have many attractions that cover several eras.

I got a tag mention from @greek-mythologies and I am almost certain you are that Anon (epic facepalm if I am wrong) but I think you are most interested in Greek mythology, right? Taking this risk, I will give you some options based on locations having some significance in the Greek mythology and the ancient epics, in an attempt to narrow it down. Because in truth, Greece has more than 100 archaeological museums - I can’t really narrow it down much! So I’ll go very specific and there’s no chance I will say all of them:

On the steps of myths and legends

Options in Sterea Hellas

You’ll go to Parthenon. Correct, Athens is a good choice. You can also see there the temple of Hephaestus, the temple of the Olympian Zeus, the Athens Academy, the Acropolis Museum, the National Archaeological Museum and a load more if you also want ancient historical sites. A little out of Athens, you can visit the temple of Poseidon in Cape Sounion.

In the region of Phocis, you can visit the Oracle of Delphi in Mount Parnassus. It has many ancient sites, most are dedicated to Apollo. 2h 40m W of Athens.

The region of Boeotia is associated with many ancient legends and literary works, such as that of Oedipus. It saw power throughout Mycaenaean and classical times. That’s where Thebes is. Nice museum and other stuff i.e the Lion of Chaeronea. 1,5 hour W of Athens.

In Aegina island you can see the temple of Aphaea and the ruins of the temple of Zeus. Touristic place, also has medieval and modern attractions. 1,5 hour E of Athens by ship.

Options in the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese is full of history but I will only mention the more mythological ones.

Corinthia is a living museum. You probably have heard of the name. A highlight will be the Temple of Apollo in the mountains. Many museums, many sites i.e Ancient Corinth. Nemea where Hercules fought the lion is there. Visiting the Corinth Canal is a must. 1h 45m S of Athens.

Lake Stymphalia, Northern Arcadia. That’s where Hercules shot down the stymphalian birds. Other than that, Arcadia is mountainous and very beautiful and has HUGE significance for Modern Greek history, because many heroes of the Greek Revolution were from there. Has lots of folk and modern history attractions. 2h 20m S of Athens.

Ancient Olympia in Elis. The location where the ancient Olympic Games took place, many monuments (i.e the ancient wrestling school) and sanctuaries to Gods there. 2h 50m SW of Athens.

Options in Thessaly

The region of Magnesia has a lot of mythological significance. Its capital city Volos is technically the expansion of the ancient city of Iolcus and that’s where Jason and the Argonauts began their journey. The symbol of the city and an attraction in its waterfront is Argo, his ship. Volos is built on the foot of Mount Pelion, which is where the Centaurs originate from. Pelion took its name from King Peleus, father of Achilles who was born there. It is also renowned for its beauty, combining forests with beaches and traditional architecture. Magnesia also has two of the most ancient settlements in Greece (from 6000 BCE), a nice archaeological museum, ancient tombs etc. Lake Karla in the lowlands is mentioned by Homer with its old name Boibeis. 4 hours N of Athens.

Just north of Magnesia, there is the region of Larisa, half of Achilles’ kingdom. The capital city has both ancient and medieval sites but the most important site is in the borders of Larisa with Pieria, where Thessaly and Macedonia meet: Mount Olympus. On the foot of Mount Olympus there is the archaeological site of Dion. Summer hiking in Olympus is stunning and you can easily reach the peak of Skolio. The two biggest peaks Mytikas (Pantheon) and Stefani (Throne of Zeus) need expertise, light equipment, summer conditions and please don’t do it unless you are an experienced climber. Climbing Olympus takes about two days in a normal pace. 6 hours N of Athens.

Options in other regions

In Epirus: the Necromanteion of Acheron. Acheron was the river where Charon took the souls of the dead and led them to Hades. The Necromanteion, the Oracle of the Dead, is located close to the mouth of the river in the region of Preveza. The whole of Epirus has breathtaking scenery. 5 hours NW of Athens.

On Crete island: The Palace of Knossos and all associated ancient sites in Heraklion. Sites of the Minoan civilization and connected to myths such as that of Theseus and the Minotaur and Daedalus and Icarus. All of Crete is stunning but there are too many things to see in just one trip. 9 hours S of Athens by ship but you can go by airplane.

In the Cyclades islands: Delos is the most important island from an archaeological and mythological standpoint, the whole island is an archaeological site and is uninhabited. Usually people visit it from the famous island of Mykonos. Naxos island has the Gate of Apollo. Milos is where Venus de Milo was created. Milos has outstanding landscapes. 5 - 6 hours E of Athens by ship. You can take the airplane for Mykonos.

In the Dodecanese islands: Rhodes and Kos islands have ancient and medieval sites of major importance like the temple of Athena Lindia in Rhodes. They are also very beautiful and big. 10 - 14 hours SE of Athens by ship. Both have airports.

In the Islands of Northeastern Aegean: Samos island with its very important sanctuary of Hera. Icaria island nearby is close to where Icarus fell when his wax wings melted from the sun. Both very beautiful and verdant, Icaria is also known for the longevity and lifestyle of its people. 9 - 10 hours E of Athens by ship.

In the Heptanese islands: Ithaca island, the birthplace and kingdom of Odysseus. Very beautiful and ideal for seclusion and peaceful vacation. Ruins of an ancient palace are being unearthed. Imagine if........! 6 hours W of Athens, with a combo of car and ship.

In Thrace: Samothrace island, far from everything and everyone, ideal for seclusion and great scenery. That’s where you can see the Sanctuary of the Great Gods and where Nike, the Winged Victory of Samothrace was sculpted. More than 11 hours NE of Athens, needs a combo of car and ship and you would probably need to throw an airplane connection with Thessaloniki in there to make it more doable.

I give you all these ideas to check photos of them and decide. You can see many in my blog too. I take Athens for granted for you and I recommend two - three of these destinations MAX. If you choose a place far away then just do Athens and that place. Don’t overdo it, it will be exhausting and you won’t get to enjoy the places and experience them properly. Good luck and happy travels x

#greece#europe#travel guide#travel#greek facts#athens#attica#boeotia#delphi#phocis#sterea hellas#central greece#thessaly#peloponnese#magnesia#larisa#corinthia#arcadia#elis#mainland#greek islands#that was long#keeping it for future references#anon#ask#mail

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Odysseus and his men blind Polyphemus the Cyclops. Geometric or Archaic vase painting, artist unknown. Now in the Archaeological Museum of Argos. Photo credit: Zde/Wikimedia Commons.

#classics#tagamemnon#Ancient Greece#Archaic Greece#Geometric Greece#classical mythology#Odyssey#The Odyssey#Odysseus#Polyphemus#art#art history#ancient art#Greek art#Ancient Greek art#Archaic Greek art#Geometric Greek art#vase painting#Archaeological Museum of Argos#violence tw#gore tw

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hermes – Messenger of the Gods

As one of the twelve Olympian gods, Hermes was an important figure and features in many ancient Greek myths. He played many roles, including being a psychopomp to the dead and the winged herald of the gods. He was also a great trickster and the god of several other domains including commerce, thieves, flocks and roads.

Quick and intelligent, Hermes had the ability to move freely between the divine and mortal worlds and it was this skill that made him perfect for the role of the gods’ messenger. In fact, he was the only Olympian god who could cross the border between the dead and the living, an ability that would come into play in several significant myths.

Who was Hermes?

Hermes was the son of Maia, one of the seven daughters of Atlas, and Zeus, the god of the sky. He was born in Arcadia on the famous Mt. Cyllene.

According to some sources, his name is derived from the Greek word ‘herma’ meaning a heap of stones like those that were used in the country as landmarks or to indicate the boundaries of the land.

Although he was a god of fertility, Hermes didn’t marry and had few affairs, compared to most other Greek gods. His consorts include Aphrodite, Merope, Dryope and Peitho. Hermes had several children including Pan, Hermaphroditus (with Aphrodite), Eudoros, Angelia and Evander.

Hermes is often depicted wearing a winged helmet, winged sandals and carrying a wand, known as the caduceus.

What Was Hermes the God Of?

Apart from being a messenger, Hermes was a god in his own right.

Hermes was the protector and patron of herdsmen, travellers, orators, literature, poets, sports and trade. He was also the god of athletic contests, heralds, diplomacy, gymnasiums, astrology and astronomy.

In certain myths, he is depicted as a clever trickster who would sometimes outwit the gods for fun or for the benefit of humankind.

Hermes was immortal, powerful and his unique skill was speed. He had the ability to make people fall asleep using his staff. He was also a psychopomp, and as such had the role of escorting the newly dead to their place in the Underworld.

Myths Involving Hermes

Hermes and the Herd of Cattle

Hermes was an impish god who was always searching for constant amusement. When he was just a baby, he stole a herd of fifty sacred cattle that belonged to his half-brother Apollo. Although he was a baby, he was strong and clever and he covered up the herd’s tracks by attaching bark to their shoes, which made it difficult for anyone to follow them. He hid the herd in a large cave in Arcadia for several days until satyrs discovered it. This is how he came to be associated with thieves.

After a hearing held by Zeus and the rest of the Olympian gods, Hermes was allowed to keep the herd which consisted of only 48 cattle since he’d already killed two of them and used their intestines to make strings for the lyre, a musical instrument he’s credited for having invented.

However, Hermes could only keep the herd if he gifted his lyre to Apollo which he willingly did. Apollo gave him a shining whip in exchange, putting him in charge of the cattle herds.

Hermes and Argos

One of the most celebrated mythical episodes involving Hermes is the killing of the many-eyed giant, Argos Panoptes. The story began with Zeus’ secret affair with Io, the Argive Nymph. Zeus’ wife Hera was quick to appear on the scene but before she could see anything, Zeus transformed Io into a white cow to hide her.

However, Hera knew of her husband’s promiscuity and was not deceived. She demanded the heifer as a gift and Zeus had no option other than to let her have it. Hera then appointed the giant Argos to guard the animal.

Zeus had to free Io so he sent Hermes to rescue her from the clutches of Argos. Hermes played beautiful music which lulled Argos to sleep and as soon as the giant was nodding off, he took his sword and slayed him. As a result, Hermes earned himself the title ‘Argeiphontes’ which means ‘Slayer of Argos’.

Hermes in the Titanomachy

In Greek mythology, the Titanomachy was a great war that took place between the Olympian gods and the Titans, the old generation of the Greek gods. It was a long war that lasted for ten years and ended when the old pantheon that was based on Mt. Othrys was defeated. Afterwards, the new pantheon of gods was established on Mt. Olympus.

Hermes was seen during the war dodging boulders thrown by the Titans, but he doesn’t have a prominent role in this great conflict. He apparently did his best to avoid it whereas Ceryx, one of his sons, fought valiantly and was killed in battle fighting Kratos, the divine personification of power or brute strength.

It’s said that Hermes bore witness to Zeus banishing the Titans to Tartarus for all eternity.

Hermes and the Trojan War

Hermes played a role in the Trojan War as mentioned in the Iliad. In one long passage, Hermes is said to have acted as a guide and counsellor to Priam, the King of Troy as he tried to retrieve the body of his son Hector who was killed at the hands of Achilles. However, Hermes actually supported the Achaeans and not the Trojans during the war.

Hermes as Messenger

As messenger to the gods, Hermes is present in several popular myths.

Hermes as Messenger

Hermes escorts Persephone from the underworld back to Demeter, her mother in the land of the living.

Hermes escorts Pandora down to earth from Mount Olympus and takes her to her husband, Epimetheus.

After Orpheus turns back, Hermes is tasked with escorting Eurydice back into the Underworld forever.

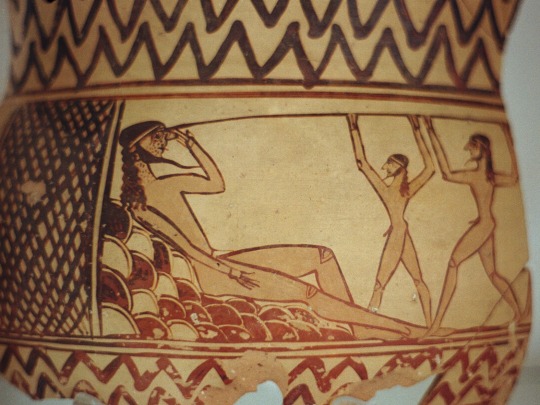

Hermes’ Symbols

Hermes is often depicted with the following symbols, which are commonly identified with him:

The Caduceus – This is the most popular symbol of Hermes, featuring two snakes wound around a winged staff. Because of its similarity to the Rod of Asclepius (the symbol of medicine) the Caduceus is often mistakenly used as a symbol of medicine.

Talaria, the Winged Sandals – The winged sandals are a popular symbol of Hermes, connecting him to speed and agile movement. The sandals were made of imperishable gold by Hephaestus, the craftsman of the gods, and they allowed Hermes to fly as fast as any bird. The winged sandals feature in the myths of Perseus and helped him in his quest to kill the Gorgon Medusa.

A Leather Pouch – The leather pouch associates Hermes with commerce. According to some accounts, Hermes used the leather pouch to keep his sandals in.

Petasos, the Winged Helmet – Such hats were worn by rural people in Ancient Greek as a sun hat. Hermes’ Petasos features wings, associating him with speed but also with the shepherds, roads and travelers.

Lyre -While the lyre is a common symbol of Apollo, it’s also a symbol of Hermes, because he is said to have invented it. It’s a representation of his skill, intelligence and quickness.

A Gallic Rooster and a Ram – In Roman mythology, Hermes (Roman equivalent Mercury) is often depicted with a rooster to herald a new day. He’s also portrayed riding on the back of a large ram, symbolizing fertility.

Phallic Imagery – Hermes was seen as a symbol of fertility and phallic imagery associated with the god were often placed at household entrances, reflecting the ancient belief that he was a symbol of household fertility.

Hermes Cult and Worship

Statues of Hermes were placed at the entrances of stadiums and gymnasiums throughout Greece because of his swiftness and athleticism. He was worshipped in Olympia where the Olympic Games was celebrated and sacrifices made to him included cakes, honey, goats, pigs and lambs.

Hermes has several cults throughout both Greece and Rome, and he was worshipped by many people. Gamblers often prayed to him for good luck and wealth and merchants worshipped him daily for successful business. People believed that Hermes’ blessings would bring them good fortune and prosperity and so they made offerings to him.

One of the oldest and most important places of worship for Hermes was Mt. Cyllene in Arcadia where he was said to have been born. From there, his cult was taken to Athens and from Athens it spread throughout Greece.

There are several statues of Hermes erected in Greece. One of the most famous statues of Hermes is known as the ‘Hermes of Olympia’ or the ‘Hermes of Praxiteles’, found amongst the ruins of a temple dedicated to Hera in Olympia. There is also priceless artwork depicting Hermes on display at the Olympian Archaeological Museum.

Hermes in Roman Tradition

In Roman tradition, Hermes is known and worshipped as Mercury. He is the Roman god of travellers, merchants, transporters of goods, tricksters and thieves. He is sometimes depicted holding a purse, which is symbolic of his usual business functions. A temple built on Aventine Hill, Rome, was dedicated to him in 495 BCE.

Facts About Hermes

1- Who are Hermes’ parents?

Hermes is the offspring of Zeus and Maia.

2- What is Hermes the god of?

Hermes is the god of boundaries, roads, commerce, thieves, athletes and shepherds.

3- Where does Hermes live?

Hermes lives on Mount Olympus as one of the Twelve Olympian gods.

4- What are Hermes’ roles?

Hermes is the herald of the gods and also a psychopomp.

5- Who are Hermes’ consorts?

Hermes consorts include Aphrodite, Merope, Dryope and Peitho.

6- Who is Hermes’ Roman equivalent?

Hermes Roman equivalent is Mercury.

7- What are Hermes’ symbols?

His symbols include caduceus, talaria, lyre, rooster and the winged helmet.

8- What are Hermes’ powers?

Hermes was known for his swiftness, intelligence and agility.

In Brief

Hermes is one of the best-loved of the Greek gods because of his cleverness, quick-wit, mischievousness and skills he possessed. As one of the twelve Olympian gods, and as the messenger of the gods, Hermes was an important figure and features in several myths.

https://symbolsage.com/hermes-god-greek-mythology/

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sparta Was Much More Than an Army of Super Warriors

https://sciencespies.com/history/sparta-was-much-more-than-an-army-of-super-warriors/

Sparta Was Much More Than an Army of Super Warriors

A monument in Thermopylae to King Leonidas. Bridgeman Images

Ancient Sparta has been held up for the last two and a half millennia as the unmatched warrior city-state, where every male was raised from infancy to fight to the death. This view, as ingrained as it is alluring, is almost entirely false.

The myth of Sparta’s martial prowess owes much of its power to a storied feat of heroism accomplished by Leonidas, king of Sparta and hero of the celebrated Battle of Thermopylae (480 B.C.). In the battle, the Persian Army crushed more than 7,000 Greeks—including 300 Spartans, who are widely and falsely believed to have been the only Greeks fighting in that battle—and went on to capture and burn Athens. Outflanked and hopelessly outnumbered, Leonidas and his men fought to the death, epitomizing Herodotus’ pronouncement that all Spartan soldiers would “abide at their posts and there conquer or die.” This singular episode of self-sacrificing bravery has long obscured our understanding of the real Sparta.

A scene from Thermopylae by the Italian novelist, painter and poet Dino Buzzati. The 300 or so Spartans helped hold off an enormous Persian Army for three days.

Luisa Ricciarini / Bridgeman Images

Actually, Spartans could be as cowardly and corrupt, as likely to surrender or flee, as any other ancient Greeks. The super-warrior myth—most recently bolstered in the special effects extravaganza 300, a movie in which Leonidas, 60 at the time of the battle, was portrayed as a hunky 36—blinds us to the real ancient Spartans. They were fallible men of flesh and bone whose biographies offer important lessons for modern people about heroism and military cunning as well as all-too-human blundering.

There is King Agis II, who bungled various maneuvers against the forces of Argos, Athens and Mantinea at the Battle of Mantinea (418 B.C.) but still managed to pull off a victory. There is the famous Admiral Lysander, whose glorious military career ended with a rash decision to rush into battle against Thebes, probably to deny glory to a domestic rival—a move that cost him his life at the Battle of Haliartus (395 B.C.). There is Callicratidas, whose pragmatism secured critical funding for the Spartan Navy in the Peloponnesian War (431-404 B.C.), but who foolishly ordered his ship to ram the Athenians’ during the Battle of Arginusae (406 B.C.), a move that saw him killed. Perhaps the clearest rebuttal of the super-warrior myth is found in the 120 elite Spartans who fought at the Battle of Sphacteria (425 B.C.); when their Athenian enemies surrounded them, they opted to surrender rather than “conquer or die.”

These Spartans, not particularly better or worse than any other ancient warriors, are just a handful of many examples that paint the real, and utterly average, picture of Spartan arms.

But it is this human reality that makes the actual Spartan warrior relatable, even sympathetic, in a way Leonidas can never be. Take the mostly forgotten general, Brasidas, who, instead of embracing death on the battlefield, was careful to survive and learn from his mistakes. Homer may have hailed Odysseus as the cleverest of the Greeks, but Brasidas was a close second.

Almost no one has heard of Brasidas. He’s not a figure immortalized in Hollywood to prop up fantasies, but a human being whose mistakes form a much more instructive arc.

He burst onto the scene in 425 B.C. during Sparta’s struggle against Athens in the Peloponnesian War, breaking through a large cordon with just 100 men to relieve the beleaguered city of Methone (modern Methoni) in southwest Greece. These heroics might have put him on track for mythic fame, but his next campaign would make that prospect far more complicated.

Storming the beach at Pylos that same year, Brasidas ordered his ship to wreck itself on the rocks so he could assault the Athenians. He then barreled down the gangplank straight into the teeth of the enemy.

It was incredibly brave. It was also incredibly stupid.

Charging packed troops, Brasidas went down in a storm of missiles before he’d made it three feet. Thucydides tells us that Brasidas “received many wounds, fainted; and falling back into the ship, his shield tumbled into the sea.” Many of us are familiar with the famous admonition of a Spartan mother to her son: “Come back with your shield or on it.” While this line is almost certainly apocryphal, losing one’s shield was nevertheless a signal dishonor. One might expect a Spartan warrior who had both lost his shield and fainted in battle to prefer death to dishonor. That’s certainly the kind of choice Leonidas is celebrated for supposedly making.

An 1888 illustration shows a bust of the ancient Greek historian and general Thucydides, known as “the father of scientific history.”

Science Photo Library

Herodotus tells us the two Spartan survivors of Thermopylae received such scorn from their city-state for having lived through a defeat that they took their own lives. But Brasidas, though surely shamed by his survival, did not commit suicide. Instead, he learned.

The following year, we see a recovered Brasidas marching north to conquer Athenian-allied cities at the head of 700 helots, members of Sparta’s reviled slave-caste, who the Spartans constantly feared would revolt. Forming this army of Brasideioi (“Brasidas’ men”) was an innovative idea, and quite possibly a dangerous one. As a solution to the city’s manpower crisis, Sparta had promised them freedom in exchange for military service. And arming and training slaves always threatened to backfire on the slavers.

This revolutionary move was matched by a revolution in Brasidas’ own personality. Far from rushing in, as he once had done, he now captured city after city from the Athenians through cunning—and without a single battle. Thucydides writes that Brasidas, “by showing himself…just and moderate toward the cities, caused most of them to revolt; and some of them he took by treason.” Brasidas let the slaves and citizens of Athenian-held cities do the dirty work for him. After one particularly tense standoff, he won the central Greek city of Megara to Sparta’s cause, then marched north, cleverly outmaneuvering the Athenian-allied Thessalians deliberately to avoid combat.

Brasidas’ foolhardy crash-landing at Pylos, in a 1913 illustration.

Bridgeman Images

Arriving at his destination in northeastern Greece, he used diplomacy, threats, showmanship and outright lies to convince the city of Akanthos to revolt from Athens and join Sparta, deftly playing on their fear of losing a harvest that had not yet been gathered. The nearby city of Stagiros came over immediately after.

But his greatest prize was Amphipolis (modern Amfipoli), a powerful city that controlled the critical crossing of the Strymon River (the modern Struma, stretching from northern Greece into Bulgaria). Launching a surprise attack, he put the city under siege—and then offered concessions that were shocking by the standards of the ancient world: free passage for any who wished to leave and a promise not to pillage the wealth of any who remained.

This incredibly risky move could have tarnished Brasidas’ reputation, making him look weak. It certainly runs counter to the myth of the Spartan super-warrior who scoffed at soft power and prized victory in battle above all else.

But it worked. The city came over to Sparta, and the refugees who fled under Brasidas’ offer of free passage took shelter with Thucydides himself in the nearby city of Eion.

Thucydides describes what happened next: “The cities subject to the Athenians, hearing of the capture of Amphipolis, and what assurance [Brasidas] brought with him, and of his gentleness besides, strongly desired innovation, and sent messengers privately inviting him to come.”

Three more cities came over to Sparta. Brasidas then took Torone (modern Toroni, just south of Thessaloniki) with the help of pro-Spartan traitors who opened the city gates for him.

The mythic Leonidas, failing in battle, consigned himself to death. The very real Brasidas, failing in battle, licked his wounds and tried something different. Charging down the gangplank at Pylos had earned him a face full of javelins. He had been lucky to survive, and the lesson he took from the experience was clear: Battle is uncertain, and bravery a mixed commodity at best. War is, at its heart, not a stage for glory but a means to advance policy and impose one’s will. Brasidas had even discovered that victory could be accomplished best without fighting.

Brasidas would make many more mistakes in his campaigns, including the one that would cost him his life outside Amphipolis, where he successfully fought off the Athenians’ attempt to recapture the greatest triumph of his career. Brasidas daringly took advantage of the enemy’s bungled retreat, attacking them and turning their withdrawal into a rout, but at the cost of his life. His funeral was held inside Amphipolis, where today you can visit his funeral box in the archaeological museum.

That he died after renouncing the caution that had marked most of his career seems fitting, a human end for a man who is the best example of the sympathetic fallibility of his city-state’s true military tradition. He is valuable to historians not just for his individual story, but moreover because he illustrates the humanity of real Spartan warriors, in direct contrast to their overblown legend.

Fallible human beings who learn from their errors can achieve great things, and that is the most inspiring lesson the true history of Sparta can teach us.

When we choose a myth over reality, we commit two crimes. The first is against the past, for truth matters. But the second, more egregious, is against ourselves: Denied the chance to see how Spartans struggled and failed and recovered and overcame, we forget that, if they did it, then maybe we can too.

Ancient Civilizations

Ancient Greece

Arts

Myth

Poetry

Warfare

#History

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Aphrodite

Statuette of Aphrodite, 1st. century BC, marble. Found near the theatre of Argos. Peloponnese. The goddess wears only a himation that leaves her right breast exposed, and treads on a goose with her left foot.

National Archaeological Museum of Athens (Athens, Greece), Inv. 3248

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Statue of Hermes Criophorus

Marble statue of a youthful Hermes with a ram.

Pentelic marble. 2nd century AD copy of a late 5th century BC original attributed to Naukydes of Argos. Found in 1890 by archaeologists of the French School in Athens, at ancient Troezen in the Peloponnese.

The god is shown naked, with a chlamys. He wears a petassos on his head. With his right hand he grasps the horns of a ram that is shown next to him, seated on its hind legs.

(National Archaeological Museum, Athens.)

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hera, has been depicted on various coins throughout history, especially in regions where her worship was prominent. Here are some key aspects:

1. Greek Coins:

- Argos: Hera was particularly revered in #Argos , and coins from this region often depicted her. These coins might feature her likeness or symbols associated with her, such as a peacock.

- Samos: As Hera was the patron goddess of #Samos , coins from this island sometimes bear her image or symbols.

2. Roman Coins:

- During the Roman period, Hera was syncretized with Juno, her Roman counterpart. Roman coins sometimes feature #Juno with attributes similar to those of Hera, such as the peacock or a diadem.

3. Iconography:

- #Hera is typically portrayed as a majestic, mature woman, often wearing a crown or diadem.

- Symbols associated with her include the peacock, a scepter, and a pomegranate.

These depictions on coins served not only a religious purpose but also a political one, emphasizing the city’s connection to divine favor and authority. #archaeology #ancient #ancienthistory #museum #numismatics #numismatist #numismatica #rarecoins #oldcoins #worldcoins

#coincollecting #coincollection #gold #metaldetecting #silvercoins

#coin #romancoin #ancientcoins #ancientgreekcoins #money #history.

#temple#art #greece #alsadeekalsadouk #الصديق_الصدوق

0 notes

Text

The fresco re-emerges in a room along Via del Vesuvio, during re-profiling interventions on the Regio V excavation fronts

Yet another female image resurfaces in the new Regio V excavations, and joins the other sophisticated female faces featured in the medallions of certain rooms along Via del Vesuvio, and in the image of Venus and Adonis from the House with the Garden, which have already been unearthed.

This time, we have the myth of Leda and the Swan depicted in a fresco, which was discovered during stabilisation and re-profiling works on the excavation fronts, in a cubiculum (bedroom) of a house along Via del Vesuvio. The room which contains the painting is located next to the entrance corridor, where the fresco of Priapus similar to that of the nearby House of the Vettii was found.

The scene - full of sensuality - depicts the union of Jupiter, transformed into a swan, and Leda, wife of King Tyndareus. From her embraces, first with Jupiter and then Tyndareus, would be born the twins Castor and Pollux from an egg (the Dioscuri), Helen - the future wife of King Menelaus of Sparta and cause of the Trojan War - and Clytemnestra, later bride (and assassin) of King Agamemnon of Argos and brother to Menelaus.

At Pompeii the episode of Jupiter and Leda enjoyed a certain measure of popularity, as evidenced in various domus, with varied iconography (the lady is generally depicted as standing, not seated as in the new fresco, and in certain cases she is not depicted in the moment of intercourse). Among the varied depictions we have are those in the Houses of the Citharode, of Venus in the Shell, of Queen Margherita, of Meleager, of the Coloured Capitals or Ariadne, of the Ancient Hunt, of Fabius Rufus, of the Fontana d’Amore, and perhaps also in the Houses of L. Rapinasius Optatus and of the Golden Cupids.

The myth of Leda and the Swan also appears in frescoes which have been detached from Herculaneum and Villa Arianna at Stabiae, which are today located at the National Archaeological Museum of Naples, and just to confirm the popularity of the subject, on a silver mirror from the Boscoreale Treasure, today displayed at the Louvre.

9 notes

·

View notes