#Anti-rop aesthetic

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

thatinsufferableb-st-rd said:

@anghraine so i have read the books multiple times and am an avid fan of the movies. I enjoy both for what they are. I think the main difference is that Peter Jackson was very open about what they chose to cut and why from anything I've ever seen. They even have Sam give a nod to the book readers by saying "by rights we shouldn't even be here". No I'm not happy about what they did with Faramir and Glorfindel got jipped, and I would have lover to have seen Elronds sons but at the end of the day there were acknowledgments of what and why. Rings of Power to me has always come off as hiding from any criticism by using the shield of "well if you don't like it it's because you don't like POCs in it". To which I genuinely could not give a fuck less, like there are so many branches of elves that went different ways so that could make sense within what Tolkein established. But don't hide behind that when your writing is just "Sauron is evil. We know. And we know she knows. But we have to make it seem like she's the only one who Has A Clue so we must all try to shoo her off to make a plotline"

@lesbiansforboromir has already correctly and politely pointed out that you are doing the very thing we were criticizing in that post—intruding on ROP fan discussion to unfavorably contrast the show to the Peter Jackson films, while also applying a degree of scrutiny to ROP that the Jackson films are rarely subject to in a remotely comparable way and could not bear. Frankly, @lesbiansforboromir is nicer and more restrained than I am about this, but you chose to tag me as well, so I'll also respond.

We (lesbiansforboromir and I) were talking about being excited about costuming in S2 of ROP and disliking the fandom meltdowns over ROP's costuming looking (somewhat) different from the films' aesthetic. Since it had already come up in their discussion, I added that I'm not convinced by the anti-ROP contingent framing their seething hatred of the costuming and design as just caring so much about fidelity to Tolkien's vision. I pointed out that Tolkien fandom broadly cares far more about their preferred, film-influenced aesthetics than Tolkien's actual descriptions and gave some specific examples of this.

There's been a lot of talk, for instance, about how the universally long, flowing hair for Elves preferred by the fandom and used in the films is actually totally canon according to Tolkien even if it's rarely mentioned in LOTR proper. This is inaccurate. Galadriel's brother Aegnor is typically depicted in the fandom/film-preferred style rather than per Tolkien's description of his hair as "strong and stiff, rising upon his head like flames" (indeed, in general neither Aegnor nor anyone else is ever depicted this way, and this description rarely shows up in the lists of "no it's about ethics in adaptation" Tolkien hair quotes).

Tolkien repeatedly describes Elvish, peredhel, and Dúnadan women as wearing their hair bound up in braided coiffures with jeweled hair pieces/nets rather than loose and flowing à la the films and the fandom. Nobody cares, any more than they care about Tolkien's description of Arwen's clothing as soft, grey, and noticeably devoid of ornamentation apart from a belt and netted cap (i.e. the opposite of her highly elaborate film costuming and typically loose, unbound, uncovered hair in the films and most illustrations).

Meanwhile, my fave Faramir's hair is nowhere near long enough in the films or most art to mingle with Éowyn's as Tolkien describes. It's usually also depicted as blond, reddish, or brown rather than black as in the book; in Tolkien's LOTR, all described Gondorians have dark or black hair, with the only difference in coloring being that some Gondorians are dark-skinned and some are pale. Again, almost nobody in the fandom cares about this when they're going on about costume design and casting to reflect Tolkien's vision, and male Gondorians are overwhelmingly depicted with short or shoulder-length hair in the films and in Tolkien illustrations.

Popular depictions of Gondor, including the Gondor of the films, very rarely reflect Tolkien's description of Gondor's aesthetic as similar to ancient Egypt, the Byzantine Empire, and the Roman Empire. Film Gondor has, at most, extremely vague allusions to Byzantine architecture amidst the general and deliberate westernization of Gondor's design—as just one example among many, Tolkien's explicitly Egyptian-based design for the royal crown of Gondor is converted to a generically western European-style crown in the films and overwhelmingly in the fandom.

I then pointed out that it's been very noticeable that ROP haters tend to have a powerful double standard wrt fidelity when it comes to the Jackson films. For over 20 years, most film fans have been constitutionally incapable of tolerating even slight criticism of the films without jumping in to defend their greatness and condescendingly explain the most basic elements of adaptation. (Yes, we know film is not the same medium as text, we know changes are part of adaptation to another medium, we all know that, we all know that a word-for-word adaptation would suck and never be made, this is not new information and does not make the PJ films' every choice a good one.) Yet most film LOTR fans who vocally despise ROP display none of the charity towards ROP that they demand for the films (demand even from someone like Christopher Tolkien, a dead man the entire fandom is deeply indebted to, whose dislike of the films still leads to regular attacks on his character from Jackson film stans).

This hypercritical yet hyperdefensive tendency in the fandom is neatly illustrated by the fact that you responded to a conversation about the double standards in evaluations of ROP's costuming vs the films' to go on about how ROP is objectively bad for reasons entirely unrelated to costuming, how you're totally not racist (something nobody was talking about), and to quote you directly, "Like the show was just Bad." Truly, an incisive critique. Meanwhile, your concessions with regard to the Jackson films are mainly about extremely minor and defensible omissions like removing Glorfindel and the sons of Elrond rather than the serious and fundamental problems that lesbiansforboromir and I have with them, or even the ways they do pretty much the exact same things you're lambasting ROP for.

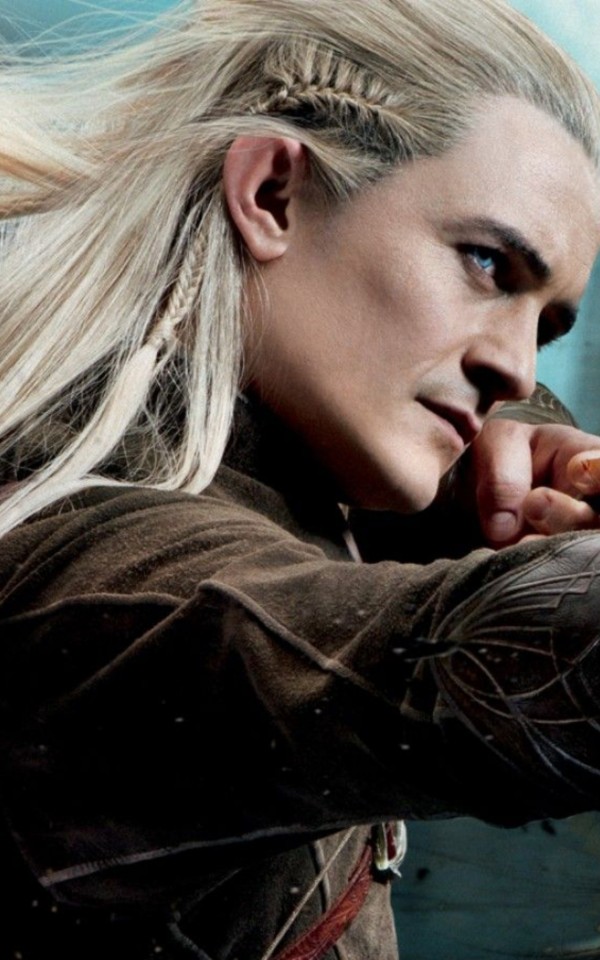

I mean, if we're going to talk about action hero Elves in ROP vs the Jackson films, what about the action hero-ification of Legolas in the films? He was described by Tolkien himself as the Fellowship member who accomplished the least, so super badass battle-skateboarding Legolas hardly represents fidelity to Tolkien's vision. Why should that get a pass while film-stanning ROP haters seethe about ROP!Galadriel being too special, even though Tolkien described her as one of the most special Elves to ever live and specifically as remarkably athletic and insightful?

Meanwhile, film Gimli is reduced to comic relief, the only dwarves taken seriously are conventionally hot ones in The Hobbit films, and Frodo's expressions of strength and fortitude are consistently removed to glorify other characters. Film Gondorians were deliberately designed to seem like useless tin soldiers (which they are in the films, as well as whiter and blonder than Tolkien wrote them) rather than the physically imposing and highly effective fighting force of the book. ROP imagining Elvish rituals upon approaching Valinor that aren't based in Tolkien canon but don't directly conflict with it is absolutely trivial compared to the films' handling of Denethor and Faramir.

The point is not that you, personally, are not allowed to like the films or dislike ROP despite all this. Many people do love the films, including most of my followers. They do have their strengths, though they are extremely racist and few film fans will acknowledge this without soft-pedaling it in some way (esp, since you brought it up, given the context of the truly unhinged degree of racism that has accompanied much of the broader discourse around ROP).

The point is that film fans who hate ROP are constantly showing up in our conversations to be "well actually ROP is just objectively bad, unlike the films, because the show has failings that are also in the films but it's totally different there because of the contents of Peter Jackson's soul" or whatever. The point is the absolutely glaring and obnoxiously hypocritical double standard of defensiveness about the films and obsessive nitpicking of ROP that leads to ROP haters continually going on rants to ROP fans that are unwelcome, uninvited, and usually (as in this case) irrelevant to what was even being discussed.

#legendarium fanwank#respuestas#anghraine rants#legendarium blogging#pj critical#tv: lotr#ondonórë blogging#long post#jrr tolkien#aegnor#arwen undómiel#peoples of middle earth#letters of jrr tolkien#faramir#legolas#galadriel

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay I can't stand it that post about the hairstyles in Star Trek Picard has activated an autism hyperfixation infodump.

I love Rings of Power and the Hobbit movies. This is not an anti-Rings of Power/Hobbit movies post or bashing either thing in any way. If you're looking for that kind of post, please keep going, I don't want to engage with that. If you're trying to avoid that kinda thing, this is mild criticism at best.

While I am fascinated with Galadriel's Rings of Power** portrayal, the lack of styling with her hair is bothering me a little bit. Like I know it's in character since her hair is extremely important to her character and the lore itself, and even in the PJ movies they kept her hair relatively simple compared to the other elves.

But, Rings of Power Galadriel is different from PJ movies Galadriel. This is a Galadriel actively participating in war, as opposed to the PJ Galadriel that is mostly working behind the scenes except for Dol Guldur. And yet, even as she's riding into what she knows is going to be a big battle for the Southlands, all that's really done with her hair is a loose, kinda messy French braid.

And like don't get me wrong, it's beautiful and very Galadriel and I am filled with jealousy because I had to trim my hair after a while without a haircut and I miss my long, loose messy French braid, but even if RoP was trying not to ape the PJ movie aesthetic completely, they still share a lot of the same visual language and those movies gave us so many examples of Elvish braids for battles/conflicts.

(side note: why is it so flipping hard to find good shots of the male elves from the side so you can see their hair?)

I'm not saying go nuts with it, far from it. But there's a way to keep it simple and Galadriel-esque without losing that visual language. Pull the hair on top back with some lace, rope or Dutch braids then braid the loose hanging hair below. Or do something similar to Haldir from Two Towers and pull it back in a simple half-up French, leaving the rest loose. Heck, even just making the braid a French fishtail to keep that sleek Elvish look but still be something that can be easily messed up for the post Mount Doom go Boom* scenes might've looked more visually Elvish than what they did.

I'm no Tolkien expert in any way, shape or form. I love the books but find his writing style somewhat of a struggle to comprehend personally, so I don't know the books inside and out like my brother does. I do love the movies and I love Rings of Power, flaws and all. I'm no hairstylist either, but I love braiding hair and mentally deconstructing how the movies did their elf hair. So, in short, I guess this is my nitpicky Tolkien adaptation opinion. Thank you for attending my TED talk.

(*and yes I know it wasn't technically called Mount Doom yet but that was the first and only thought that went through my head during that scene and I think it's funny, so.)

(**Sorry I had to mildly edit this because i glanced at it and realized I wasn't clear, this is specifically about RoP Galadriel, not movie Galadriel. But really I like all the Galadriels so *shrug*)

#K8 Rambles about Middle Earth#middle earth#tolkien stuff#rings of power#lord of the rings#lotr films#the hobbit#the hobbit films#K8 Rambles about Hair Braiding#hairstyling stuff#galadriel#rop galadriel#(I don't know how to tag Tolkien stuff so I'm just chucking in whatever comes to mind)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

To me, it is political in the sense that the clothes that are being made now are low quality, damaging to the environment, mass produced with cheap labor in unsafe working conditions, and most of it goes to the trash because we simply do not need this much clothes, we didn't asked for this yet they sell it to us as if we did. In the name of capitalism and endless growth. I do not hate modern clothes for their aesthetics, quite the opposite, I like modern fashion a lot. What I don't like is all the evil that is behind its production. RoP feels like the TV equivalent of fast fashion. So does the MCU, and most (all?) major blockbusters. Some of which I do like! A lot them actually. But that feels barely relevant on the wider context of "the people who made this are overworked, underpaid, not properly credited, and the whole process of creating it is very bad for the earth". That is political, to me.

I am not a racist. People of color in Middle Earth is nice and good and even necessary, if you will. I am however anti-capitalist, and that's the political statement on my part.

For no particular reason, I just feel like being clear. I love old fashioned clothing styles. Like, chances are, I'll like anything designed 1000 years ago more than what we have today. This is an aesthetic preference. It is not political. It does not mean anything secret, and it's not a societal criticism. When I yearn for the way fabric used to be made, for the styles, for the tailoring, I'm not saying I'd rather live then than now. I'm not touching any of that. It is very literally just an aesthetic appreciation.

In the same vein, I hate RoP. I hate it with a burning passion. I resent that it exists. This is because of my rage towards Amazon as well as my opinion that it is a disgusting, poorly written, insult of a cash grab that I won't often dignify by even discussing. My issue with it is NOT, however, the diverse casting. My hatred for RoP is not, in other words, coded racism. I don't play games like that. I'm a straightforward person. Personally I think diversity in middle earth is good, though I wish we'd get a good animated series. I think live action is always going to be in competition with Jackson's work, and it's gonna lose.

Anyway. That's all I wanted to say. Just for the record.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lucifer as the Liberator of Women

"Satanic Feminism: Lucifer as the Liberator of Women in 19th century Literature" Per Faxneld

Riveting academic texts are a basilisk among published literature, one hears of them but only a handful have ever existed. "Satanic Feminism, Lucifer as the Liberator of Women in 19th century Literature", Per Faxneld's Oxford published opus, is that rarified animal that seems impossible even as it is in our midst.

Originally a doctoral thesis published in a very exclusive run of 100 copies in 2014 (that has since gone for eye watering amounts on the grey market), Oxford University Press has brought it out for the wider audience it truly deserves.

Faxneld, who may be academia's most exceptionally dressed author, takes us on a journey that spans several centuries, yet focuses on the evolution of the Satanic figure from various perspectives over the course of the 19th century. Its a wild ride through the creative arts that reflect on the Satanic figure as illuminator and emancipator of women.

Tracing the history of the relationship between women and Satan from Eve's "fall" in the Garden in Genesis 3, through the later church doctrine in relation to women and onward it begins in earnest with Milton's majestic Lucifer in the mid 17th century.

Faxneld provides the reader with a constantly evolving cast of literary and creative figures who bore the torch of 'Lucifer as Liberator' throughout the 19th century. From Milton's influence on successive generations of writers and artists we are introduced to the Romantics and their Socialist ilk, Byron, Shelley, and most importantly, the connection between Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, author of Frankenstein and wife of Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley to her socialist anarchist parents from a previous generation of women's liberators.

Then through the 19th century Faxneld uncovers Blavatsky's specious feminism, the mad hypocrisy of the Decadents in France, the Symbolists and Suffragettes and Feminists who were shaping popular thought and drawing literary and aesthetic connections between Lucifer the Rebel and Women as Rebels. Along the way we meet women of amazing character, devilish power, and anti patriarchal might, suffragettes, actors, poets, and their legion of detractors and commentators.

What sets "Satanic Feminism" apart from a standard text is its academic structure, originally a doctoral thesis Faxneld has done the research - revealing a multilingual asset to academic scholarship that is so lacking in the 21st century and an inspiration to read. His exquisite deductions, sourcing from English, French, German, Swedish and other written texts, ample presentation of centuries of commentary and counterpoint on each avenue of inquiry, and generous footnotes are incredible.

The binding and production are standard and well done by Oxford, the book's layout and footnoting system are particularly well done and as a tool for research the book has been designed in an absolutely perfect manner. Other publishers of academic studies should take note. This is how it's done. Footnotes at the bottom of the page, detailed index and bibliography all at the end.

Beyond the well trodden names in literature Faxneld digs deep, bringing up obscure (to modern readers at least) authors and artists like Catulle Mendès, Jules Michelet, Renée Vivien, Mary MacLane, Félicen Rops, and Stanislaw Przybyszewski. Authors and creators whose vision of Satan has wend its way through popular culture despite their current obscurity.

Faxneld takes the task of understanding the role of women as "witches", as "demons", "lesbians" and all of the outcast variables that could be projected upon them by christian society and sees it for its true self. He presents the path of inversion that runs through the narrative of liberated women as "witch" in the eyes of a patriarchal society. Presenting the revelatory concept that these artists and authors have chosen to embrace terms intended as derogatory and make them hallmarks of their behavior and spirit. To embody the liberated woman as demon, as witch.

Given the current state of world affairs I think "Satanic Feminism" could not have come at a better time. It is a must read for both witch and women's studies scholar alike. A vast trove of amazing literature, liberated women, and the tantalizing lives of those who fought against the patriarchy in the 19th century under the common banner of Satan.

Do not miss this work as it is sure to become a primary sourcebook of women's studies over the next decade.

Get yourself a copy from Oxford:

"Satanic Feminism, Lucifer as the Liberator of Women in 19th century Literature" Per Faxneld

#skeptical occultist#occult books#occult#magic#witch#witchcraft#folkwitch#occulture#grimoires#alchemy#necromancy#satanism#satanic feminism#cursos online#charm#witchy#cunning craft#lhp#lwa#exu#lucifer#lilith#renee vivien#per faxneld#oxford#demon#decadent

275 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyperallergic: How a 19th-Century Painter Turned from Reality to Fantasy

Henri Fantin-Latour, “La Lecture” (1877), oil on canvas, 97,2 x 130,3 cm (Lyon, Musée des Beaux-Arts © musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, photo by Alain Basset)

PARIS — Henri Fantin-Latour’s 19th-century Realist paintings in À fleur de peau at the Musée du Luxembourg remind us that the real must be processed through the flesh and the blood of our eyes. In his early, clear-eyed (yet lovely) paintings that celebrate the luxury of the senses, it is certainly the case that Fantin-Latour’s subject was the reality of the observable world itself. So, in wake of the post-factual politics that brought so much ugliness to the fore with the foul and despicable Donald Trump, it was something of a tonic to peruse Fantin-Latour’s early, unambiguous paintings of substantial, precise, and graspable realities. The mysterious attraction I found in this enlightening retrospective, which includes over 120 paintings, lithographs, drawings, photographs, and preparatory studies, involved taking seriously what one can easily enjoy.

Fantin-Latour’s still life and group portraits accept the powers of observation while rejecting Romantic, exaggerated emotionalism. In the Realist tradition of Gustave Courbet that Fantin-Latour followed, what is intellectually valued is a certain jubilant, but humble, vision typical of science. But as evident in his relatively early painting of flowers and fruit, like “Still Life: Engagement” (1869), Fantin-Latour replaces mere science-based, objective realism with something more seductive. This is especially evident in the sumptuous depiction of the wineglass.

Henri Fantin-Latour, “Roses” (1889), oil on canvas, 44 x 56 cm (collection of Musée des Beaux-Arts Lyon, © musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, photo by Alain Basset)

Fantin-Latour painted a great number of such flower paintings over his career, as we see with the much later, but stylistically consistent, “Roses” (1889), a painting that demonstrates his talent for the balanced composition of bouquets as well as an exceptional virtuosity in capturing glass textures. These paintings of objective phenomena are like boring relatives we never visit and rarely think about but never doubt the existence of, even though in reality they might have completely changed. Perhaps that is why Fantin-Latour’s conservative-in-style still life paintings sold well and brought him some fame. Indeed, Marcel Proust mentions Fantin-Latour’s work in his masterpiece In Search of Lost Time.

Fantin-Latour’s choice of subject matter — what he makes “real” — does not really matter that much. Painting from photographs, he made some great group portraitures too, such as “Homage to Delacroix” (1864). This large, dark painting is based on a photograph taken 10 years earlier of writers and artists clustered around a portrait of Eugène Delacroix. A year after Delacroix’s death, Fantin-Latour painted it to pay the artist greater homage than he had received in his lifetime. Included in the painting are Fantin-Latour himself (in white shirt, holding a palette), and the painters James Whistler and Edouard Manet. Also featured is the author of Les Fleurs du mal, poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire, who is seated in the lower right-hand corner. This painting, like “A Studio in Les Batignolles” (1870) or “The Reading” (1877), makes use of the realistic but dusty grays of Jean-François Millet, as in his “ The Gleaners” (1857).

Henri Fantin-Latour, “Hommage à Delacroix” (1864), oil on canvas, 160 × 250 cm (Collection of Musée d’Orsay through a 1906 gift by Etienne Moreau-Nélaton, image via Wikimedia Commons)

In his unjustly forgotten early self-portraits, such as “Self-portrait with Slightly Lowered Head” (1861), Fantin-Latour’s self-image becomes another fact of the observable world. Whether stiffly posed or more intimate, such as here, these self-portrait paintings demonstrate his sure hand and acute observational skills that he developed at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where he devoted much time to copying the works of the Old Masters in the Musée du Louvre.

We gain a glimpse into Fantin-Latour’s creative process in the painting “The Birthday” (1876), which is accompanied by lithographs and drawings that were reworked several times over during 1875, the year the artist married Victoria Dubourg, a fellow painter with whom he collaborated on occasion. The retrospective also provides a rare opportunity to study the artist’s collection of cheesy photographs of naked women that he used to draw from in preparation for his paintings.

Installation view of Henri Fantin-Latour: A fleur de peau at Musée du Luxembourg (image © Rmn-Grand Palais, photo by Didier Plowy)

Toward the end of his career, it becomes clear that faithful reproductions of reality no longer satisfied the artist. Fantin-Latour undercuts the theory of his earlier work with an unexpected series of fuzzy paintings of fairies — something from outside the observable world. Placed next to or against his earlier embrace of bourgeois vision, this late work dealing with fantasy and seduction is incongruous. Here, desire becomes every bit as objective as cut flowers or bearded men in a room.

With this turn, Fantin-Latour veers towards Symbolism, a movement that was a strange amalgam of the social turmoil of its times, its authors swerving between an aesthetics based on effortless asceticism (such as with Odilon Redon and Gustave Moreau) and the decadent debauches associated with Joris-Karl Huysmans, Félicien Rops, and Oscar Wilde. The Symbolists’ political associations were equally split between Catholic right-wing nationalism and anarchist individualism. But either way, Symbolism suggested that reality is a construct, and as such is somewhat fragile. Things neither exist nor fail to exist — they are simply important or unimportant.

Henri Fantin-Latour, “Un atelier aux Batignolles” (1870), oil on canvas (collection of Musée d’Orsay, image via Wikimedia Commons)

This we see in the anti-realist fairy picture “The Night” (1897) and other gauzy works. Nourished by his passion for music and inspired by mythological subjects or odes to the beauty of the female body in the guise of chaste allegories, this work reveals the artist’s lesser-known forays into English Romanticism. Just consider the work of Henry Singleton, Henry Howard, Frank Howard, and Joshua Cristall — all of whom worked at some point in the tradition of small-scale paintings depicting dainty fairy affairs. These artists led the way to the recognized school of Victorian fairy painting, one which had as its admirers luminaries such as Lewis Carroll, William Makepeace Thackeray, Charles Dickens, and John Ruskin, who gave a lecture called Fairy Land in the early 1880s. Under Queen Victoria, fairy paintings appeared systematically in Royal Academy exhibitions (replete at times with their soft, dreamy, erotic imagery) throughout the 19th century.

Henri Fantin-Latour, “La Nuit” (1897) oil on canvas, 61 x 75 cm (image courtesy Musée d’Orsay © Rmn-Grand Palais (musée d’Orsay), photo by Hervé Lewandowsk)

In these later works, Fantin-Latour affirms the palpable reality of seductive phenomena and reconsiders what constitutes the “real.” His earlier, austere Realist art arranged facts and transmitted them to the picture plane; these hyper-lucid paintings seem to affirm “objective reality” as the functional ideal of painting. Perhaps that is why he first tried to oppose Impressionism’s immediacy, the instantaneity of things and their changing appearance in light. In Impressionism one observes phenomena (ironically) too real to be captured in the perfect and complete pictures that are deemed realistic. But, later in life, Fantin-Latour seems to have realized he had ignored the deeper reality of the seduction of the imaginary and its alternative factual intensity.

Henri Fantin-Latour: À fleur de peau continues at the Musée du Luxembourg (19 Rue de Vaugirard, 75006 Paris) through February 12. The show will travel to the Musée de Grenoble (5 Place de Lavalette, 38000 Grenoble, France) March 18–June 18.

The post How a 19th-Century Painter Turned from Reality to Fantasy appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2kbgIxT via IFTTT

0 notes