#And the general unrest in the middle East makes me suspect its more likely to be that

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"I hope it remains a rumour and not news" to me sounds like something much more serious than idle paddock driver movement gossip or team ownership.

The rumours about Abu Dhabi potentially being in danger of cancellation sound more likely to me?

#f1#Travel advice has just been updated warning people to be wary of travelling to the UAE#And the general unrest in the middle East makes me suspect its more likely to be that#Drivers are going to move teams or retire at some point it's not like a journalist is going to hope that never happens#I also doubt they're that attached to the strolls#A race being cancelled though is something none of them want to happen#Especially not for humanitarian reasons

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Love After the Fact Chapter 23: Duct and Cover

I stand by this terrible pun

First Previous Next

Pidge adjusted their eyeware, inspecting the Balmeran crystals Hunk had brought them. “Yes, these should do. Thank you.”

“Of course. Shay was happy for an excuse to call her brother.”

“The brother who hates you?”

“That’s the one.”

“Mnh. I’ll never understand that man. Oh! How is Shay? She's pretty far along now, right?”

“She’s due in a few phoebs. And she’s well, thanks for asking. Chasing after Rosetta is becoming difficult. I might see if Lance wants to borrow her. Get his baby fix.”

“You people. Squirting your DNA at each other. So uncivilized. So underevolved.”

“Whatever you say, Pidge.”

“Keith agrees with me.”

“For now… So what are you gonna do with the crystals?”

Pidge rummages around their workroom, digging for their toolkit. “Well, I stumbled across some old research of Alfor’s. Before Lance was born, he’d been looking into whether Balmeran crystals are biocompatible. Things that are compatible for some other species, like coral or ceramic, are not compatible with Alteans, limiting the use of more advanced prosthetics and cosmetic modifications. Alfor suggested that due to its unique ability to absorb, store, and distribute quintessence, Balmeran crystal might be biocompatible.

“But after Lance was born, he just kind of… discarded it.”

“That’s brilliant, Pidge. Have you contacted Ryner back on Olkarion?”

“Yes. She’s fascinated by the idea. As am I.” Pidge finally found their toolkit under a pile of digital blueprints of a Galran barrow. “It’ll be tricky. There are so many variables. I’ve also requested samples from Balmera T-672 and B-43 for comparison.”

Hunk carefully clears a space at Pidge’s worktable so they can lay out the crystal samples. “It’s okay, right? To hand off Rosetta to Keith and Lance? I mean, it won’t make Keith uncomfortable or anything?”

“Pfft. No. He threw someone across the training room the other day because they asked why they should take orders from a ‘stunted little freak’. Apparently they forgot exactly who they were talking to. If you came onto him he might be uncomfortable, but other than that, I think you’ll be fine.”

“So what are we doing exactly?” Hunk asked, passing a small toolkit and a camera to Pidge. They climb up into the ducts, arranging supplies.

“I am sneaking into Alfor’s lab to eavesdrop. You are going to be my backup. I’d let you be my full partner in this, but if you get fired, your family will starve. If I get fired, I live here in the ducts and make Alfor’s life hell.”

“You say as you make me your accessory in this crime. Also, I thought you had a feed in there.”

“Eh, Lance’ll come through for you. I have faith. I did, but it’s gone now. Like, the entire unit has been removed and destroyed. He probably suspects it’s me, but I used a generic device just in case.”

“I suppose… Why specifically are you sneaking into Alfor’s lab?” Hunk passes up a coil of rope. They have more advanced toys, of course, but sometimes Pidge likes to go back to the basics.

“Because. Lance says that there’s a rumor going around that there’s still unrest between Altea and Daibazaal. He’s got his cronies, that is you, me, Adam, and Lanval, running around trying to find the truth in it. Alfor spends almost all of his time in there, but he’s in the training yard right now, so it might be our chance.”

“But…” Hunk twiddles his thumbs. “It’s just court gossip, right? Totally nothing.”

Pidge presses their long, long fingers to their forehead. “Hunk, gossip is never ‘just’ gossip. Like legends, there’s always some truth to it. Comms check.”

“Comms check,” Hunk repeats, adjusting the mic dangling from his earpiece as Pidge’s voice chimes.

“Comms are go.” Pidge gets on their belly in the duct, crawling forward with the rope slung over their shoulder, toolkit at their belt, a camera strapped to their head. They activate a tiny, holographic map set into a device on their wrist. “You know, I’ve been thinking a lot about armor lately.”

“Could you think about it later? Y'know, when we're not about to get our asses court martialed?”

“And more discreet weapons. Teleporting, returning weapons? And like, better shields? Oooh, how about- oof!” Pidge rubs the top of their head, grimacing as their feelers trembled with the duct's reverb. They’d run into the wall of the duct. Hmm… do they go left, or right? They check their map. Right.

“How about you pay attention to what you’re doing right now?” Hunk mumbles. Pidge rolls their eyes. “And we can talk about armor later, after we’ve gotten away with treason.”

“‘Kay.” Pidge crawls along. “Found it,” they whisper, carefully popping out a vent like the one they crawled through. The gripping pads of their fingers cling to the metal, making sure it doesn't clatter to the ground.

“What do you see?”

“Hm. A ton of nothing.” There’s nothing. Well, actually there’s a ton of stuff. Alembics, beakers, flasks, test tubes, burners, scales, weird stuff in jars, a suspension chamber, quintessence capsules full of glowing blue liquid… It’s just an alchemy lab, albeit an incredibly well-supplied one. “I’m going to descend.”

Reaching the floor, there’s still nothing. Pidge looks around tilting their head so that their asymmetrical ears catch more sounds. Humming emptiness. “Something’s definitely off.”

“How so?” Hunk whispers, leaning forward to eye Pidge’s feed. The young Olkari runs their spindly fingers over a table. It comes up- “Is that dust?”

“Yes,” Pidge whispers. “Why? How? Alfor enters this room every day after breakfast and doesn’t leave until it’s at least time for dinner.”

“Maybe he’s using another table?”

Pidge hums skeptically, but checks around. Everything is dusty. They study the wear patterns in the floor. Too much wear. There's dust collected under the tables, but everywhere open is clear, thanks to the stupid cloaks these royals wear. Clearly, Alfor had paced and flitted all over this lab at one point. “No good. Hmm…”

Pidge pulls up their map of the ducts, notices a large space right next to the lab. “Hunk, can you check the castle map? I want to know what’s next to the lab on the east side.”

“Sure.” Pidge waits. “Pidge? Yeah, there’s nothing. Just space.”

“Yeah, right. I’m so sure.” Pidge shimmies up the rope back into the duct, replacing the vent one they’re back in. Negative space can be tricky. There’s no telling what’s in negative space. “Scanning for surveillance… Scan complete. No surveillance equipment detected, but I am detecting electronics. Okay so if I cut here-” Pidge indicates a panel in the duct. “I should be able to see something. If not, we’ll go from there.”

They pull out a miniature blow torch, cutting a hole in the side of the duct. They love this kind of work. It’s fun playing Lance’s spy.

“Okay, friend. Please be careful. And don’t do anything that’ll make Shay a widow, okay?”

“I will. And I won’t. I promise. As soon as I’m done, you can go back to your gross domestic life.” Pidge finishes with the duct.

“Uh-huh. Speaking of my gross domestic life, are you still coming over for dinner tomorrow?”

“Absolutely! It’s been ages since I saw Rosetta! Okay.” Pidge sticks the adhesive pads of their fingers to the siding, pushing it out so they can turn it to fit through the hole they’ve made. “Woah.”

“Woah,” Hunk parrots. “That explains the electronics you detected. What are we looking at?”

Pidge stares down at a large room of holographs and screens. In the middle of the room, there’s a particularly large table with a holographic top. Hovering, glittering in the dim room, is a perfect three-dimensional replica of Daibazaal. “A war room. We’re looking at a war room.”

Holding the panel of the duct steady with their sticky fingers, Pidge carefully seals the cut out section back into place. They lay on their stomach in the duct, thinking.

“Oh mother earth, are we still at war? Has this all been for nothing? What if-”

“Most likely scenario is that Alfor doesn’t trust the Galra. The one thing he’s very good at is killing people. He’s probably planning for just in case.”

“Okay, but what if he’s not? If we go to war again, the first thing that’s going to happen is that Keith will be killed! Not to mention Allura and Romelle in the fallout. Even Keith couldn’t fight off the entire Altean Army!”

“No, he couldn’t. We don’t have time right now to go in and see what’s up, so in the meantime, we’ll make plans of our own. Lance won’t stand for this. He, Keith, Allura, Romelle, and Lotor have already given up so much for this alliance, and every time Lance reaches out to Daibazaal for advice they’ve been nothing but cordial and helpful. He’ll likely side with them. At this point, the Galra are more likely to do well by his people.”

“And we’ll side with him, right?”

“Absolutely.” It’s not even a question for Pidge.

“We have to tell him, don’t we,” hunk murmurs, saying it more as a statement than a question. “Before we figure out what’s really going on?”

“He sent us here. He’ll expect a report today and knows we can deliver.”

“Keith only just started to feel safe here.”

“Yeah.” Pidge sighs, scoots backward, working their way through the ducts until they land feet-first in their workroom. “But if Alfor can plot and scheme, then so can we.”

“Uh-huh. But… Maybe we could…” Hunk fidgets. “Scheme tomorrow?”

Pidge sighs, smiles at their friend. “Sure, Hunk. We’ll scheme tomorrow. I’ll brief Lance myself. Thanks for the crystals.”

Hunk picks Pidge up in a tight hug. “You’re welcome. Let me know if you need more. And I’ll see you tomorrow for dinner. We can put the baby to bed and scheme over alcohol that's not nunvil.”

Pidge smiles wider, waves as Hunk leaves. Once he’s gone, they let their smile drop. Had they both really agreed to betray Altea so easily?

Quiznak, this place is such a mess.

#LoveAftertheFact#LAtF#klance#galtean au#altean lance#galra keith#adashi#altean adam#galra shiro#voltron legendary defender#vld

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

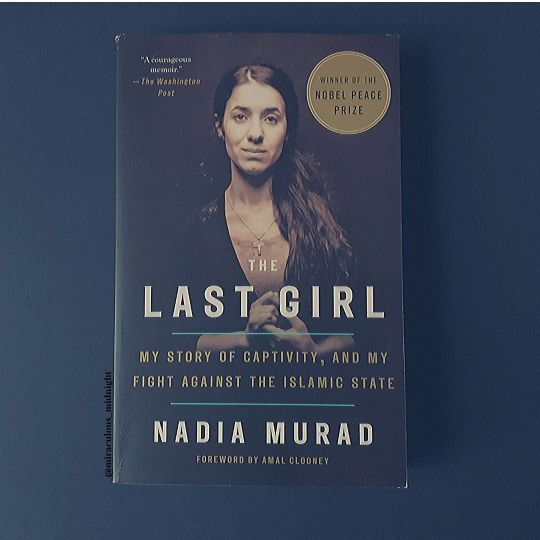

The Last Girl Review

The Last Girl: My Story of Captivity, and My Fight Against the Islamic State

By Nadia Murad

5/5 stars

While some progress has been made in the fight against ISIS, as argued by Nadia Murad in The Last Girl, the problems in Iraq cannot be clearly divided along a line that is determined to label every Muslim as a terrorist. In fact, Murad approaches the controversial topic from a new outlook: the rise of the Islamic State and its supporters has been years in the making, ever since American intervention took down Saddam Hussein and his Baathist institutions. She also explains the situation in Iraq as a religious persecution as ISIS targeted members of religious minorities living in the nation, including Murad herself. In her book, Murad not only argues for the dismantling of the Islamic State but also the humanization and protection of the innocent people who still remain under ISIS control. Her powerful memoir deserves more attention as it is a necessary read in order to fully understand the inner workings of Iraq’s many religious sects as well as a different and relevant, non-western feminist perspective of women living in the Middle East. Through her narrative style, Murad effectively persuades her audience of the need for religious acceptance of the Yazidi people and on a larger scale, the prosecution of the Islamic State for genocide.

Split into three parts, the memoir begins with a historical account of Iraq that explains the rise of ISIS. Starting with Saddam Hussein’s control over the nation and its eventual liberation by Americans in the early 2000s, Murad paints a historical backdrop that informs the reader of decades of political unrest and recurring violence, interwoven with anecdotes from her childhood and the days leading up to the ISIS capture of her village, Kocho. From the tension between political parties, like the Kurdistan Democratic Party and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan to the growing separation between Yazidis and their Sunni Arab neighbors, one is lead to believe that it was only a matter of time before the temporary bubble of peace that Murad had lived in her entire life popped.

The second section of the memoir begins with the corralling of Murad and her village into the public school. That day, six of her brothers along with the rest of the male residents of Kocho were killed. Murad and the women and children were taken to a secondary location, where she and her young female relatives were separated from Murad’s mother. Murad would later find out that every elderly woman from Kocho, including her mother, was executed and buried in an unmarked grave. Meanwhile, Murad and the young women were sold into slavery, forced to become “sabaya” or sex slaves for ISIS soldiers and high-ranking officers.

After a failed attempt, Murad managed to escape for a second time and find a sympathetic Sunni Arab family that would hide her from ISIS. From this home, she contacted one of her brothers, who was outside the country at the time and able to smuggle her into Kurdistan controlled territory. While her brother worked to help their female relatives and other women escape enslavement, Murad became an activist against ISIS and human trafficking, later speaking in front of the United Nations and winning the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize.

An integral part of The Last Girl as well as Murad herself is the Yazidi religion, which should be protected and accepted across the world, as Murad argues. “Yazidis believe that before God made man, he created seven divine beings, often called angels, who were manifestations of himself,” according to Murad (27). One of these angels, Tawusi Melek (or the Peacock Angel), is the main being to which Yazidis pray and center their practices and celebrations around. However, many Muslim Iraqis consider Yazidis “devil worshippers,” scorning them and their practices for “reasons that have no real roots” in the stories of Yazidis (Murad 28). As a result of this hatred, “outside powers had tried to destroy [Yazidis] seventy-three times” before the genocide of Murad’s people in 2014 (Murad 6). It is this hatred and derision, Murad argues, that led ISIS to target Yazidis in their terrorist campaign. As a religious minority in Iraq, Yazidis relied on the relationship that they had with Sunni Arabs for protection. But as many Sunni Arabs turned to the Islamic State, Yazidis were left vulnerable to the whims of ISIS. As Murad conveys, the acceptance of the Yazidi religion, and religious tolerance on a broader scale, would further prevent the violence and persecution that often follows minorities.

In order to accept and protect Yazidis, one must first become educated on their religious practices and culture. Murad asserts that “Yazidism should be taught in schools from across Iraq to the United States, so that people understood the value of preserving an ancient religion and protecting the people who follow it” (300). In a broader sense, people who are better informed about Yazidism and its history as a persecuted community would be able to better help the Yazidis still under ISIS rule, especially the women forced into sexual slavery. The Last Girl is a moving story and a major contribution to understanding the role of transnational feminisms. It is important to note that while many Yazidi practices and the general attitudes in Iraq reinforce gender inequality, Murad is not arguing for a complete cultural upheaval of these practices and attitudes; she is pushing for what may seem like a small step to western feminists, but freeing the large Yazidi population of women still kept in sexual slavery is what is needed for the feminism that Murad practices, for the betterment of Yazidis, and for a longer path towards female empowerment in the Middle East.

Although Murad advocates for the prevention of Yazidi persecution through religious tolerance, she also wants justice for the crimes committed against her and her people. Murad argues that the Islamic State, “from the leaders down to the citizens who supported their atrocities,” should be put on an international trial for the genocide of the Yazidi people and other war crimes (300). Not only has ISIS executed the majority of Murad’s village, including her mother and brothers, but it has also committed horrific acts of cruelty and continues to do so today in the form of rape and other torture. Murad states that when she fantasizes about putting ISIS on trial, she sees her first rapist, Hajij Salman, captured alive, and as she further describes: “I want to visit him in jail [...] And I want him to look at me and remember what he did to me and understand that this is why he will never be free again” (177). For Murad, holding ISIS responsible for its crimes against humanity is not just for Yazidi justice, it’s personal, and reasonably so. No one should have to go through such unimaginable torture, especially without any form of justice.

In the epilogue of The Last Girl, Mura writes that “the UN finally recognized what ISIS did to Yazidis as a genocide” (304). But without a trial, justice does not exist for Murad and her people. Recognition is not enough. And the longer the UN waits to prosecute the Islamic State, more evidence of its crimes will continue to disappear. But for Murad, the time for waiting is over. Her memoir is not only a testament to her survival and her love for her people but also her unwillingness to let ISIS go unpunished. The Last Girl is evidence, Murad’s written evidence, of the Islamic State’s atrocities. As a survivor, this book is her way of holding ISIS accountable for its crimes. It is an act of defiance that will continue to be a relevant and necessary read for the public until ISIS is formally punished.

Murad’s memoir perfectly conveys her intentions through an effectively enticing narrative that urges the reader to better empathize with the struggles of the Yazidi people and understand the importance of prosecuting the Islamic State on a grand scale. Although this is not a revolutionary take on feminism, it is a compelling story that portrays a nation racked with terrorism in a new light. While Murad’s memoir educates as well as connects western readers to the plight of her people, it also highlights a path to resolving conflict in Iraq from the perspective of those who know the region and its culture best. In order to help her people, Murad argues that one must first understand her history and culture. While the punishment of ISIS is imperative, it is not enough to employ airstrikes on suspected terrorist headquarters. Organizations, like the Islamic State, will only continue to reform as violence, religious persecution of minority groups, and the poor treatment of women persists.

Thanks for reading! I hope you enjoyed this review! Check out my other reviews here!

Credit: Murad, Nadia. The Last Girl: My Story of Captivity, and My Fight Against the Islamic State. New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2017.

#book review#book#books#the last girl#nadia murad#yazidi#islam#inclusive feminism#feminsim#book reviews#book review blog#review#bookreviews#2019 reads#2020 review#book reccs#miraculousmidnightreviews#book reccomendation#reading#book photography

10 notes

·

View notes