#And immigrated to the U.S. when his grandmother was a baby

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Soap: We need you to translate this document that’s in Spanish

Sweetie: I can’t read this

Soap: ???? You speak Spanish with your mom on the phone all the time

Sweetie: First of all, that’s my grandma. Second of all, I am HORRIBLE at speaking Spanish and have no idea how to read or write it.

Soap: Are you fucking serious?

#Info dumping about Sweetie in the tags cause I can#His maternal great grandparents are from Puerto Rico#And immigrated to the U.S. when his grandmother was a baby#They made home in Texas specifically#Both of his parents were also born in Texas but immigrated to the UK shortly before his mother became pregnant with him#Which is why he speaks differently than a usual person from the UK#since both of his parents since still had pretty heavy accents in his developmental years and he was homeschooled for a long time#Lucas Sweetie Baker#call of duty#cod#john mactavish#john soap mactavish#quotes by ghost

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

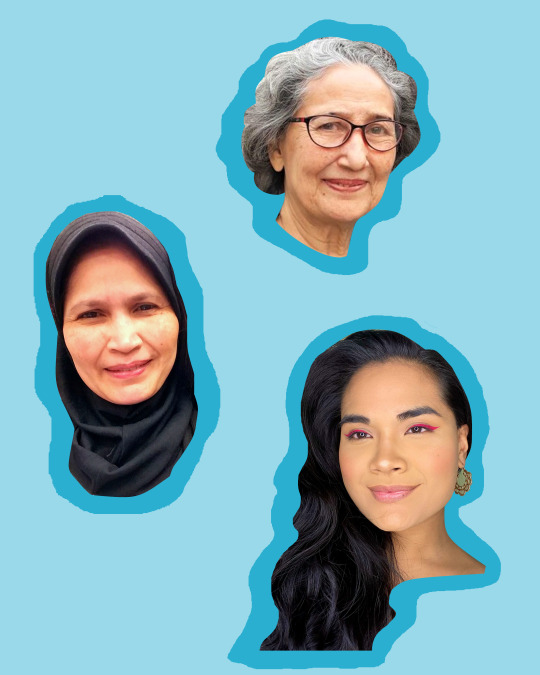

New Releases

Sometimes in dark moments books can allow us to escape to other worlds, other times and lift our spirits. Here are three new releases this week to help give us comfort during this dark time.

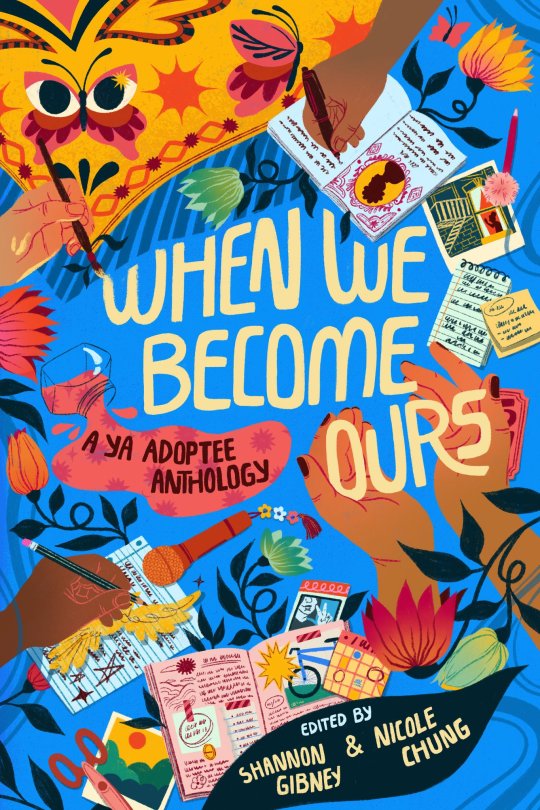

When We Become Ours: A YA Adoptee Anthology edited by Shannon Gibney & Nicole Chung Harper Teen

Two teens take the stage and find their voice. . . A girl learns about her heritage and begins to find her community. . . A sister is haunted by the ghosts of loved ones lost. . . There is no universal adoption experience, and no two adoptees have the same story. This anthology for teens edited by Shannon Gibney and Nicole Chung contains a wide range of powerful, poignant, and evocative stories in a variety of genres. These tales from fifteen bestselling, acclaimed, and emerging adoptee authors genuinely and authentically reflect the complexity, breadth, and depth of adoptee experiences. This groundbreaking collection centers what it’s like growing up as an adoptee. These are stories by adoptees, for adoptees, reclaiming their own narrative.

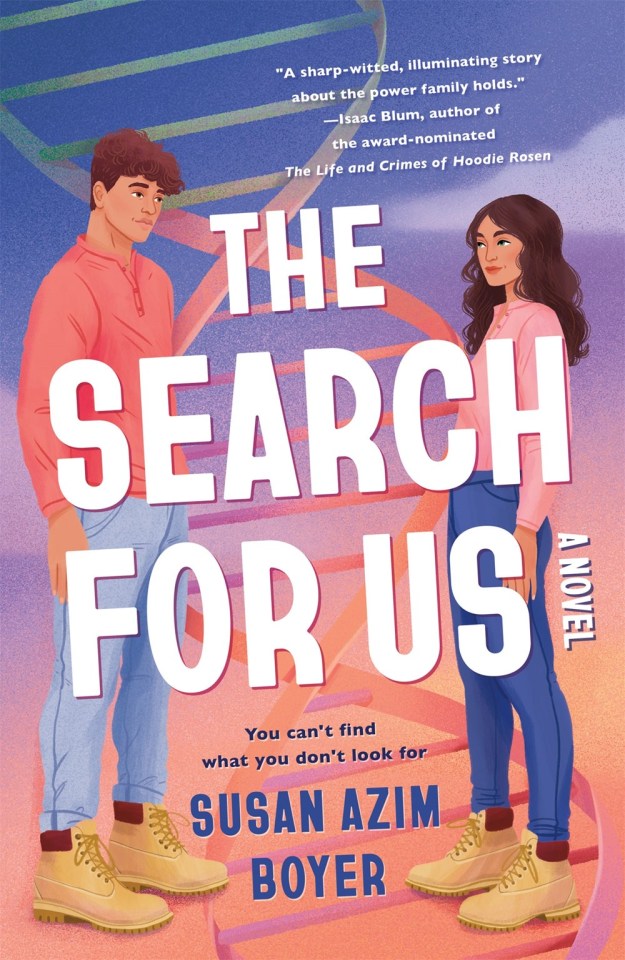

The Search for Us by Susan Azim Boyer Wednesday Books

Two half-siblings who have never met embark on a search together for the Iranian immigrant and U.S. Army veteran father they never knew. Samira Murphy will do anything to keep her fractured family from falling apart, including caring for her widowed grandmother and getting her older brother into recovery for alcohol addiction. With attendance at her dream college on the line, she takes a long shot DNA test to find the support she so desperately needs from a father she hasn’t seen since she was a baby. Henry Owen is torn between his well-meaning but unreliable bio-mom and his overly strict aunt and uncle, who stepped in to raise him but don’t seem to see him for who he is. Looking to forge a stronger connection to his own identity, he takes a DNA test to find the one person who might love him for exactly who he is―the biological father he never knew. Instead of a DNA match with their father, Samira and Henry are matched with each other. They begin to search for their father together and slowly unravel the difficult truth of their shared past, forming a connection that only siblings can have and recovering precious parts of their past that have been lost. Brimming with emotional resonance, Susan Azim Boyer’s The Search for Us beautifully renders what it means to find your place in the world through the deep and abiding power of family.

Sleepless in Dubai by Sajni Patel Amulet Books

In this hate-to-love teen rom-com from the author of My Sister’s Big Fat Indian Wedding, Nikki, an aspiring photographer, accompanies her family on a trip to Dubai to celebrate the five days of Diwali in style. It should be the trip of a lifetime, if Yash, the boy next door–with whom Nikki has a rocky history–weren’t on board. Oblivious to the tension, Nikki’s matchmaking family encourages Nikki to get better acquainted with Yash. Turns out a lot can change on a 12-hour flight beyond just continents. But can betrayals and conflicting ambitions be set aside long enough for the two teens to discover the true meaning of the Festival of Lights?

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

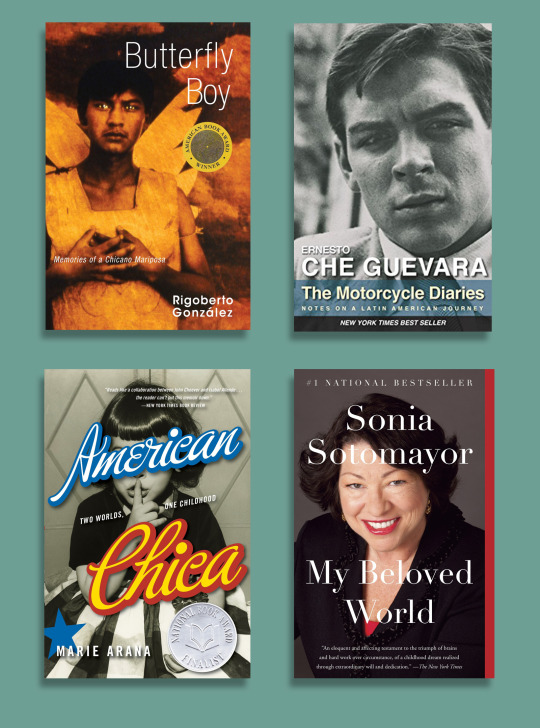

Weekend Edition: Latinx Memoirs

This weekend we’re taking a look at memoirs by Latinx authors. There are many titles to choose from right here at OCL, but don’t forget that you can also check out books through OhioLINK and SearchOhio for even more options.

Butterfly Boy: Memories of a Chicano Mariposa by Rigoberto González Heartbreaking, poetic, and intensely personal, this is a unique coming-out and coming-of-age story of a first-generation Chicano who trades one life for another, only to discover that history and memory are not exchangeable or forgettable. Growing up among poor migrant Mexican farmworkers, Gonzaĺez also faces the pressure of coming-of-age as a gay man in a culture that prizes machismo. Losing his mother when he is twelve, Gonzaĺez must then confront his father's abandonment and an abiding sense of cultural estrangement. His only sense of connection gets forged in a violent relationship with an older man. By finding his calling as a writer, and by revisiting the relationship with his father during a trip to Mexico, Gonzaĺez finally claims his identity at the intersection of race, class, and sexuality. The result is a leap of faith that every reader who ever felt like an outsider will immediately recognize.--From publisher description

The Motorcycle Diaries by Ernesto Che Guevara The diaries written by Che Guevara during his riotous motorcycle odyssey around South America at the age of twenty-three.

American Chica: Two Worlds, One Childhood by Maria Arana From her father's genteel Peruvian family, Marie Arana was taught to be a proper lady, yet from her mother's American family she learned to shoot a gun, break a horse, and snap a chicken's neck for dinner. Arana shuttled easily between these deeply separate cultures for years. But only when she immigrated with her family to the United States did she come to understand that she was a hybrid American, an individual whose cultural identity was split in half. Coming to terms with this split is at the heart of this graceful, beautifully realized portrait of a child who "was a north-south collision, a New World fusion. An Americanchica." Through Arana's eyes the reader will discover not only the diverse, earthquake-prone terrain of Peru, charged with ghosts of history and mythology, but also the vast prairie lands of Wyoming, "grave-slab flat," and hemmed by mountains. In these landscapes resides a fierce and colorful cast of family members who bring herhistoriavividly to life, among them Arana's proud paternal grandfather, Victor Manuel Arana Sobrevilla, who one day simply stopped coming down the stairs; her dazzling maternal grandmother, Rosa Cisneros y Cisneros, "clicking through the house as if she were making her way onstage"; Grandpa Doc, her maternal grandfather, who, by example, taught her about the constancy of love. But most important are Arana's parents, Jorge and Marie. He a brilliant engineer, she a talented musician. For more than half a century these two passionate, strong-willed people struggled to overcome the bicultural tensions in their marriage and, finally, to prevail.

My Beloved World by Sonia Sotomayor The first Hispanic and third woman appointed to the United States Supreme Court, Sonia Sotomayor has become an instant American icon. Now, with a candor and intimacy never undertaken by a sitting Justice, she recounts her life from a Bronx housing project to the federal bench, a journey that offers an inspiring testament to her own extraordinary determination and the power of believing in oneself. Here is the story of a precarious childhood, with an alcoholic father (who would die when she was nine) and a devoted but overburdened mother, and of the refuge a little girl took from the turmoil at home with her passionately spirited paternal grandmother. But it was when she was diagnosed with juvenile diabetes that the precocious Sonia recognized she must ultimately depend on herself. She would learn to give herself the insulin shots she needed to survive and soon imagined a path to a different life. With only television characters for her professional role models, and little understanding of what was involved, she determined to become a lawyer, a dream that would sustain her on an unlikely course, from valedictorian of her high school class to the highest honors at Princeton, Yale Law School, the New York County District Attorney's office, private practice, and appointment to the Federal District Court before the age of forty. Along the way we see how she was shaped by her invaluable mentors, a failed marriage, and the modern version of extended family she has created from cherished friends and their children. Through her still-astonished eyes, America's infinite possibilities are envisioned anew in this warm and honest book, destined to become a classic of self-invention and self-discovery.

La Distancia Entre Nosotros by Reyna Grande "Cuando el padre de Reyna Grande deja a su esposa y sus tres hijos atrás en un pueblo de México para hacer el peligroso viaje a través de la frontera a los Estados Unidos, promete que pronto regresará; con el dinero suficiente para construir la casa de sus sueños. Sus promesas se vuelven más difíciles de creer cuando los meses de espera se convierten en años. Cuando se lleva a su esposa para reunirse con él, Reyna y sus hermanos son depositados en el hogar ya sobrecargado de su abuela paterna, Evila, una mujer endurecida por la vida. Los tres hermanos se ven obligados a cuidar de sí mismos. En los juegos infantiles encuentran una manera de olvidar el dolor del abandono y a resolver problemas de adultos. Cuando su madre regresa, la reunión sienta las bases para un capítulo nuevo y dramático en la vida de Reyna: su propio viaje a El otro lado para vivir con el hombre que ha poseído su imaginación durante años-- su padre ausente."--Book cover

In the Country We Love: My Family Divided by Diane Guerrero ; with Michelle Burford “ Diane Guerrero, the television actress from the megahit Orange is the New Black and Jane the Virgin, was just fourteen years old on the day her parents and brother were arrested and deported to Colombia while she was at school. Born in the U.S., Guerrero was able to remain in the country and continue her education, depending on the kindness of family friends who took her in and helped her build a life and a successful acting career for herself, without the support system of her family. In the Country We Love is a moving, heartbreaking story of one woman's extraordinary resilience in the face of the nightmarish struggles of undocumented residents in this country. There are over 11 million undocumented immigrants living in the US, many of whom have citizen children, whose lives here are just as precarious, and whose stories haven't been told. Written with Michelle Burford, this memoir is a tale of personal triumph that also casts a much-needed light on the fears that haunt the daily existence of families likes the author's and on a system that fails them over and over"-- Provided by publisher

When I Was Puerto Rican by Esmeralda Santiago [The author's] story begins in rural Puerto Rico, where her warring parents and seven siblings led a life of uproar, but one full of love and tenderness as well. Growing up, Esmeralda learned the proper way to eat a guava, the sound of the tree frogs in the mango groves at night, the taste of the delectable sausage called morcilla, and the formula for ushering a dead baby's soul to heaven. But just when Esmeralda seemed to have learned everything, she was taken to New York City, where the rules - and the language - were bewilderingly different. How Esmeralda overcame adversity, won acceptance to New York City's High School of Performing Arts, and then went on to Harvard, where she graduated with highest honors, is a record of a tremendous journey by a truly remarkable woman.-BooksInPrint.

#oberlin college libraries#oberlin college#OCLReads#OCL Reading Challenge#Reading Challenge#Book Bingo#Latinx Memoir#Latinx Biography

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

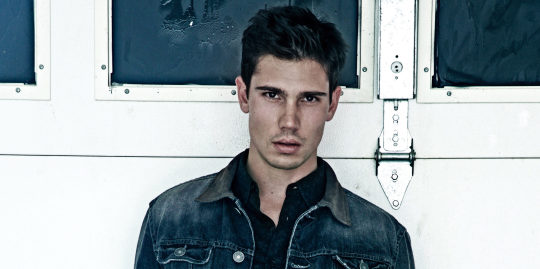

It’s been just a little over a year since “Liberty Biberty” became a part of our cultural vernacular, but that’s when Tanner Novlan garnered national attention as the tongue-tied, clueless, narcissistic actor in Liberty Mutual’s line of popular commercials. “I had seen the series they were doing of Liberty Mutual commercials in front of the Statue of Liberty,” Novlan relays. “And yes, people do come up to me all the time and say, ‘Liberty Biberty.’ It’s so fun that everyone can relate to that obnoxious actor. He was so much fun to play. When you get BOLD AND BEAUTIFUL, you’re like, ‘Wow, this is a career-changer,’ but for a funny little commercial like that, you never think [like that].”

Novlan auditioned for B&B in March and landed the part but couldn’t start, or even talk about it, until the soap began production over four months later due to the coronavirus pandemic. “I don’t know their old way of filming, so this is my new normal,” the actor relays. “Being the first production in North America to be back, it was amazing. It’s like, ‘This really is the new normal.’ It’s been such a unique process but it’s been amazing how all the producers have come together to figure this out and put forth these groundbreaking guidelines, making things safe and efficient and being able to work around all of this and keep everything alive. They’ve come up with some really creative ways of making shots work, but also feeling natural. Yes, we have to socially distance. We always are wearing our masks so we’re very cautious in that manner, but when you get into the scene and you’re reading opposite Jacqui [MacInnes Wood, Steffy], even if she is off camera, the connection is there, and I think it comes through.”

Novlan is thankful that he had some inside knowledge of how things worked at B&B, since he’s the real-life husband of B&B alum Kayla Ewell (ex-Caitlin). “It’s so perfect to have someone who has already been a part of the family to walk me through this,” he says. “She’s great for advice, and not just on work stuff. She gives me advice all the time on life. Listen to your wife. It’s always a good idea [laughs]. But with this team, I feel like I can ask any questions, and everyone was welcoming and straightforward.” Novlan and Ewell’s real-life love story sounds like it could be part of a soap, too. “It was technically kind of a setup because we both starred in this music video for an Australian band [circa 2009],” he relays. “The band is called Sick Puppies. It was one of their first hit North American releases. The name of the song was called ‘Maybe’ [which can currently be viewed on YouTube]. So, that’s how we met, on this music video at 3:30 in the morn- ing in the high desert [of California], which is where I met the woman of my dreams. We were very professional on set, but there was definitely something special about her — and I held her sunglasses for ransom. We were shooting outdoors and locations were changing and the makeup lady accidentally took our sunglasses home with her. The next day she called and said, ‘I have your sunglasses.’ I went and picked them up. I saw hers sitting there and thought, ‘I’ll give these to Kayla,’ so I snagged them and I said to her, ‘Lunch and your sunglasses?’ Luckily she took the lunch, probably just to get her sunglasses back.”

The rest was history, and the duo has worked to navigate the demands of their chosen profession. “The job sometimes involves distance and being away from one another, and there is also the time away that certain projects can require,” he points out. “It can be difficult sometimes but the trick is, we try very hard to make sure our schedules coordinate so we can be with each other. We have a two- to three-week rule where if one of us is away working for that long, you have to fly out and see the other. It’s almost like a must. And with our new baby, Poppy, we’ll definitely make sure that’s the case. But that’s the beauty of a having a great job like B&B. Luckily, I’m here. I’m local in L.A.” Novlan’s mom, a B&B super-fan, couldn’t be more thrilled about her son’s new gig. “My hometown has 500 people in it,” he explains. “I come from a very small farming community so even just coming home was a shock to her, but she’s cool. Kayla is so down-to-earth that none of that mattered. But believe me, my mother is chomping at the bit to come and visit the set of B&B as soon as COVID [passes]. That may be the real challenge, like, ‘Mom, you can’t wander onto the set. You’ve got to stay over here.’ That’s going to be a great day when it happens.”

Novlan credits his mother’s influence for getting him from Saskatchewan to Hollywood. “My mother was originally from Sacramento so I always thought it would be great to come and work in the U.S.,” he explains. “I started doing some print work in Canada so that’s how I originally came down, but I fell in love with acting as my immigration papers were being processed. I went to acting class here but I never could I have imagined having a career in film. But when I came down here and got a taste of it I was, like, ‘Wow. I’m hooked. This is it.’ ” But he admits he had no idea what he was in for. “My first job was a commercial for T.J. Maxx, back to school,” he recalls. “It was the first audition that I had ever been on and I got it and I thought, ‘Well, this is easy!’ I quickly learned there’s a lot of training that goes into it. So, I came here quite green but over the years, I’ve been able to call it a career.”

Over the next decade-plus, Novlan landed high-profile roles in MODERN FAMILY, ROSWELL, NEW MEXICO, the TV rom-com MY BEST FRIEND’S CHRISTMAS and the upcoming PUCKHEADS.

He’s up for a ROSWELL comeback, schedule permitting. “There could be a chance that we might see Gregory again,” he notes of playing the caring brother of series regular Tyler Blackburn (Alex; ex-Ian, DAYS et al). “I know ROSWELL has been picked up for a season 3, and the character has been pretty well-received from the fans, as well, which is always amazing and such an honor. You never know. It was a great experience, but right now, everything is about B&B. Even with COVID, we’re finding a really nice groove with maintaining safety while keeping that classic B&B look. It’s been pretty smooth, I’ve got to say. How lucky am I?”

“Sinn” City

B&B fans have dubbed Steffy and Finn “Sinn”, which is just fine by Jacqueline MacInnes Wood (Steffy). “I told him this character is his own,” she says. “He’s not a recast, so I told him, ‘Make it your own and have fun with it. Even though we are eight feet away from each other in scenes, feel free to play with me. Let’s connect as much as we can in these scenes.’ He’s been great. He’s been absolutely wonderful on set and taking direction very well — and he’s a fellow Canadian so, of course, we hit it off immediately. He’s a really sweet guy and he can keep up with our pace. I think the fans will really like him.”

Just The Facts

Birthday: April 9 Hails

From: Paradise Hill, Saskatchewan, Canada

My Girls: Married to Kayla Ewell (ex-Caitlin, B&B) since September 12, 2015. They welcomed daughter Poppy Marie on July 16, 2019.

What The Puck? “I grew up playing hockey, and I like to play hockey once a week with a group of actors. We have these really intense games.”

All The Right Steff: “It’s time that Steffy meets a man with a new set of values, and a new version of what passion and love can bring. She just had her daughter and I think she’s ready. Finn seems to have her best interests in mind, and I think that’s a good thing for Steffy.”

Finn In A Nutshell: “Helping people is in his nature but he can get a little too involved, and that can also get him into trouble.”

Grandma’s Boy: “My grandmother is in Canada in a nursing home and the last FaceTime I got was from my mom asking me to help set up grandma’s DVR. They’re very excited about this, and it’s nice to know that my grandma gets to see me every day — and, she’s super-proud that I’m a doctor!”

#tanner novlan#gregory manes#fingers crossed he'll be back#roswell new mexico s3#bold and the beautiful#rnm cast interviews#i hope his mom gets to visit the set#and how sweet is that his grandma gets to watch him on tv every day#my heaaaart

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

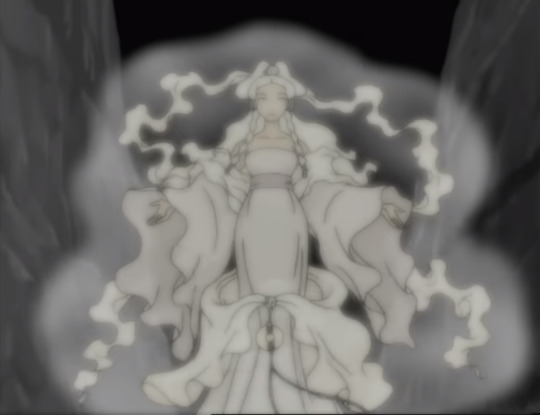

Avatar: The Last Airbender’s Princess Yue and the Cycle of the Sacrificing Woman

[Credit: Nickelodeon]

This piece is part of @syfy‘s Fangrrls vertical

Amidst the atypical state of the quarantine, the release of Avatar: The Last Airbender on Netflix has given me and other fans of the series something familiar to hold onto. In revisiting this favorite childhood show of mine, I sought Princess Yue's storyline with clarity. Although brief, it strikes all too familiarly; like the legacy of the women in my family, Princess Yue speaks to the aptitude of women who sacrifice.

Princess Yue is the daughter of Chief Arnook and his wife, a tribal chieftain. Unlike the other babies of the Northern Water Tribe, Yue was not born wailing. Sick and weak at birth, she could barely open her eyes. Members of the water tribe believed Yue was destined to die. Defeated, her father begged for his daughter's salvation before the moon.

When my Dutch grandmother was 9, her father was assigned to Indonesia as part of his government service job. She and her family relocated to the city of Padang, the capital of the West Sumatra province. Not long after the relocation, her mother died of cervical cancer. With the new absence of a mother figure and lack of familiarity with a new country, adapting was her sole option to fight for what remained of her future and family.

While Yue and Avatar's main protagonists Aang, Katara, and Sokka look out into the night sky, Yue explains her own relationship to the moon. "My father pleaded with the spirits to save me," she recalls to the other three. "That night — beneath the full moon — he brought me to the oasis and placed me in the pond. My dark hair turned white. I opened my eyes and began to cry, and they knew I would live. That's why my mother named me Yue. For the moon."

Before my grandmother married my Indonesian grandfather, who is Muslim, she converted out of Christianity. Having already left Holland, her conversion to Islam established the new life she would soon build with the man she loved. It was a sacrifice of her ancestry only she could understand. It was a sacrifice not only out of circumstantial choices but also out of promise.

For this reason, I see my grandmother as the moon of our family tree. In Avatar, Yue says, "[...] the moon was the first waterbender. Our ancestors saw how it pushed and pulled the tides, and learned how to do it themselves."

Like a moon, the cycle repeats itself.

[Credit: Nickelodeon]

My family and I immigrated from Indonesia to the United States in 2007, leaving our extended families behind, including my grandmother. Approaching U.S. Customs at the airport, my mother took off her hijab, erasing the marker of her Muslim identity. She was nonchalant, but I remember it as clear as the blue sea.

"[In Indonesian:] I was OK with it", she recently explained to me over the phone. "I was searching for ‘safe'. I didn't feel pressured or forced to." Although firm in her strength in recalling her feelings, I heard the shake in her voice. She sounded like water.

"I felt guilty," she admitted. "Sometimes I get sad seeing women who are brave enough to wear hijabs out in public. It makes me jealous."

"What does Dad say?"

"He says, ‘What makes you feel more at peace — follow that path.'"

I understand where she gets her integrity from. Listening to her and feeling my grandmother in my mother's conviction felt like witnessing the moon and ocean in motion. In this, I saw the spirits of Tui and La.

Tui and La mean "push and pull," Spirit Koh, one of the most knowledgeable spirits in the Avatar universe, tells Aang. "And that has been the nature of their relationship for all time [...] Tui and La — your moon and ocean — have always circled each other in an eternal dance. They balance each other, yin and yang."

Considering America's anti-Islam rhetoric after 9/11, my mother did what she deemed necessary at the airport. In order to enter America smoothly and without the religious bias of those who had power to accept or deny our entry, she sacrificed a visible part of herself, a momentary surrender with the promise of resistance.

Before moving to the States permanently, we moved throughout the Indonesian islands frequently, too. Traveling was meaningful not only because it gave us fond memories, but because we traveled as a unit. My mother always dreamed of having a family of five, so she had three children — me the youngest. As a nuclear Indonesian family, moving to the United States would allow us to achieve the American brand of success. However, the adjustment of living in America altered our standing as a family, breaking my mother's picture-perfect family mentality.

[Credit: Nickelodeon]

In Book 1's finale of Avatar, the Fire Nation invades the Northern Water Tribe as part of their greater mission to take over the world. Leading the Fire Nation Navy, Admiral Zhao kills the moon spirit Tui, whose physical form was the white koi fish. The Northern Water Tribe loses its balance and therefore the ability to waterbend.

Moving as a kid wasn't so much a sacrifice for me, but transitioning was. My sacrifice rifted with the sacrifices of the women before me. My transition felt selfish and destructive to my family.

Aware the moon's power remained inside of her since her father's plea, Yue gives back her life to save Tui, the white koi fish. Yue's sacrifice restores balance, even at the cost of herself. But Yue does not die — she reemerges as the Moon Spirit. She reminds her lover, Sokka, "I'll always be with you," before fading into the moon.

Oftentimes, I sense a familial grieving of the person I once used to be. Reintroducing myself to the world, saying, "I am a girl," does not discount who I was and am in spirit. Sacrificing my past froze my family rather than propelled. But ice is still a form of water, and time thaws.

When my dad took away my makeup as a denial of my femininity, I sat on the stoop of our house. A house in America, occupied by Muslim immigrants, descendant of an interracial marriage. We've come so far from where we began, yet it was everything I never asked for. My mother stepped outside to sit with me and slipped me a $100 bill.

"Go buy new ones," she smiled.

My grandmother, mother, and I sacrificed our legacies across oceans, religions, and genders. The act of sacrifice cycles itself down generationally. Like the moon, we set to rise. Like the ocean, we ebb to tide.

These days, I find it easy to accept the coexistence of contraries. Accepting my life as a woman required the rejection of what my family believed I ought to be. When I see more and more of my mother in my reflection, it is not because we are women. It is because we sacrifice. She understands the selflessness of surrender, and I know she learned that from her own mother; to give for the taking, to hide for the priding, to shed for the sprouting. This duality keeps the world spinning.

After Yue's sacrifice, her father, Chief Arnook, professed to Sokka as they stared into the moon's horizon: "The spirits gave me a vision when Yue was born. I saw a beautiful brave young woman become the moon spirit. I knew this day would come."

"You must be proud," Sokka responds.

"So proud. And sad."

***

[Credit: Decoding Ellipses]

#avatar#avatar: the last airbender#ATLA#avatar the last airbender#aang#katara#sokka#yue#princess yue#tui#la#spirit koh#admiral zhao#moon spirit#moon#sacrifice#lgbt#trans#transgender#syfy#fangrrls#syfy wire#yin and yang#tui and la#tui la#waterbender#tlok#the legend of korra#avatar: the legend of korra#korra

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

In October 2015, I found myself in a frightening situation: My name and face on a Neo-Nazi website identifying me as a Jew along with several hundred other Jews in politics, civics, and philanthropy. The website, which I will not name, warned its readers that Jews were too influential in American life; that we were a corruptive influence on America. While it didn’t advocate actually killing me, I was marked as a person to be silenced.

“How likely are these people to actually kill me?” I asked the expert at the Southern Poverty Law Center, an anti-hate group that researches white supremacist groups. I had called them seeking answers. My husband was sitting beside me, his face full of fear. I felt a tiny kick, a flutter inside me, my hands dropping to my belly. “I should probably mention that I am 8 months pregnant.”

There was a pause at the end of the line. “It’s very rare for these threats to escalate offline,” the nice man began. “They want to scare you. They want to scare you so much you decide that you never want to write again. That’s their goal. What you decide to do next is a personal decision.”

You can see that I decided to keep writing. But thinking back on the advice he gave me, it almost seems quaint: In the four years since those threats, especially since the 2016 election, white supremacists spewing anti-Semitic hatred have marched in Charlottesville chanting “Jews will not replace us,” shot up synagogues in Pittsburgh and California, and murdered gay Jewish student Blaze Bernstein. Anti-Semitic assaults are up 105% since 2017, according to the Anti-Defamation League’s annual audit on American anti-Semitism. More Jews have been killed in anti-Semitic violence around the world in 2018 than in the last several decades, according to the Kantor Center, based out of Tel Aviv University, which researches and analyzes global anti-Semitism. In New York City, a major center of Jewish culture and life, the NYPD has reported an 82% spike in anti-Semitic hate crimes in 2019. In fact, Jews are reporting the highest number of religion-based hate crimes — this is particularly troubling given that Jews are only approximately 2.2% of the U.S. adult population.

And while the majority of incidents and assaults are committed by white supremacists on the right, there has been a concerning spike in incidents and rhetoric from the left wing, too...

As a child growing up in Boston, I knew anti-Semitism existed. I even experienced it from time to time — including when my childhood synagogue was defaced with a swastika. But overall I felt safe in America... I was grateful for a country that had provided Jews with peace and prosperity. America was a rare safe place for us.

Today, that’s different. The baby I was pregnant with is now a thriving, rambunctious toddler. But when we tour Jewish preschools, my first question isn’t about education philosophy, recess or student teacher ratios — it’s always about security. In just a few short years we’ve gone from history to fear.

To understand what can be done, first we need to understand what it is: Anti-Semitism is the hatred of Jews as a distinct people, as opposed to anti-Judaism that targets our religious beliefs and practices. Anti-semitism is a conspiracy theory. It depicts Jews as a cabal secretly controlling the world for evil ends, hurting innocent people to further greedy, cruel agendas. How those agendas manifest changes based on your worldview. If you are far left, it may be that Jews are imperialists who start wars to enrich themselves. If you’re a white nationalist, it’s that Jews are the ringleaders of the White Genocide. If you’re Minister Louis Farrakhan, it’s that Jews were the secret orchestrators of the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Anti-Semitism is an ancient, chameleonic monster. It adapts to circumstances and seemingly new excuses for age-old prejudices to take hold. This is especially true in periods of political and economic insecurity.

...It doesn't help that we are also living in an era when conspiracy theories can so easily spread (from anti-Obama birtherism to Pizzagate to QAnon). President Trump and his cohorts on the far right capitalize and promote them, fomenting hatred and division through fake news and an assault on the truth. They accuse prominent Jews like George Soros of treacherous crimes, while consorting with and justifying white supremacists and their actions (“very fine people” Trump called them.). They act shocked and appalled when fear mongering, the mainstream legitimization of white nationalists, and dangerously lax gun control leave them with blood on their hands (as it did at Pittsburgh's Tree of Life synagogue).

And yet while I fear anti-Semitism on the right will lead to more violence, I fear anti-Semitism on the left will cause that violence and hate to go unchallenged. As American Jews face rising hate crimes and domestic terrorism, progressives have grappled with a string of unsettling scandals. At first, it was the way left wing groups downplayed anti-Semitism. In the wake of the 2016 election, for example, the Women’s March conspicuously left anti-Semitism off its unity principles, while left wing groups erased it as a core issue in Charlottesville, and were silent during hundreds of JCC bomb threats. Then it got worse. The anti-Semitism scandal surrounding Women’s March leadership unfolded over several tense months, during which they publicly associated with anti-Semitic Farrakhan and engaged in anti-Semitic dog whistling and bullying.

This controversy was followed by statements by freshman Representative Ilhan Omar, in which she fell into anti-Semitic tropes referencing dual loyalty, foreign allegiance, and Jewish money in her criticisms of Israel. Omar had many defenders who dismissed the charges because Omar herself faces Islamophobia and racism. But such tropes do feed the beast. As Ilhan Omar struggled to contain criticism and put forth multiple apologies for her comments, David Duke, the Grand Wizard of the KKK, came to her defense dubbing her the “Most Important Member of Congress.” It’s not to say that Omar should be held accountable for the words of David Duke. But it does indicate the way anti-Semitism — be it from the left or the right — can connect to amplify the threat.

While the Women’s March has taken positive steps to mend fences, like expanding Jewish leadership in the organization and including Jewish women in their Unity Principles, and Omar and the New York Times have apologized, the situations have led to increased division as anti-Semitism continues to spread, and becomes a political wedge issue, all of which creates increased danger for the Jewish community. In a time of increased concern about Jewish security, these scandals have had a devastating emotional impact on the Jewish community. We were taught by our grandmothers to watch for signs of danger — hateful words from across the political spectrum is one of them.

Over the past three years, I have seen anti-Semitism break and undermine strong community relationships and budding movements for justice. This what anti-Semitism does: It attacks democracy and transparency, giving authoritarian actors scapegoats for national problems. It endangers women, people of color, and immigrants as it strengthens and animates white nationalism, xenophobia, and extremist movements.

American Jews know this intrinsically and are frightened. The jump from hate speech to exterminatory violence has been a short one in the history of global Jewry. Many of us were taught about the dangers of anti-Semitism and how quickly it could rise against us from very young ages, especially for those of us who had family who were Holocaust survivors or who endured violence against Jews in the Middle East or Soviet Union. We need Americans to listen to our fear and take a stand.

The first step is to call it out when we see it in our houses of worship, living rooms, libraries, college campuses and kindergartens. This doesn’t mean we dismiss or “cancel” our friends, families, colleagues, and community leaders who engage in anti-Semitism. It means we tell them they are wrong. We educate. Jewish history is over 5,000 years old, and learning what narratives have been used to oppress Jews can be lifesaving. And then, let’s build relationships between communities that are under attack and frightened.

...This is what we need to do for each other: Come together to fight not just anti-Semitism but racism, misogyny, transphobia, homophobia, ableism, Islamophobia, and xenophobia. If we learn each other’s histories, warning signs and dangers and fight for each other, we can make the monsters afraid of us.

366 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nurses Against Circumcision

Childbirth is miraculous, beautiful, traumatic, and overwhelming, all at the same time, for both the baby and the mother. But for many children born today, squeezing through the birth canal is the easy part. Soon after birth, males born to North American women routinely face amputation of a fully functioning, healthy organ – the foreskin.

Circumcision is so commonplace in North America, it has long been considered the norm. The World Health Organization estimates the male circumcision rate in the U.S. to be 76% to 92%, while the rates in most of the Western European countries are less than 20%. Globally, more than 80% of the world’s men are left intact. An intact penis is not rare – an intact penis is the norm.

Medical professionals tell parents that circumcision is relatively painless, just a snip and it is over. Nothing could be further from the truth. Aside from the rare but possible complications, which include mutilation of the penis or death, the practice of circumcision is painful and traumatic.

The following nurses have come forward to share their knowledge and experience, to tell the truth about this practice.

Related: Circumcision Linked to Sudden Infant Death Syndrome

Nicole, A Former Nursing Student

A few years ago, I began an OB/GYN hospital clinical as a student nurse. One day, I was enlisted to attend a ‘routine circumcision.

… I did not anticipate the lurching sensation that gripped my heart as I looked upon that baby. He was laying strapped down to a table, so small and new – pure and innocent – trusting – all alone – no defenses.

I walked toward the baby and wanted to take him off the table and shelter him – to tell him that it would be okay, that nobody would hurt him on my watch.

Then in walked the doctor. Loud. Obnoxious. Joking with his assistant. As if he was about to perform a 10-minute oil change.

Not once did he talk to this little baby. I am not sure he even looked at him – really looked at him.

Rather, he reached for his cold metal instruments and then reached out for his object of mutilation: this sweet newborn’s perfect, unharmed, intact penis.

I recall this little baby boy’s screams of pain and terror – his small lungs barely able to keep up with his cries and gasps for breath.

I turned in horror as I saw the doctor forcefully rip and pull the baby’s foreskin up and around a metal object.

Then out came the knife. Cut. Cut. Cut. Screaming. Blood.

I stood next to the baby and said, “You’re almost done sweetie. Almost done. There, done.”

Then came the words from the doctor, as that son-of-a-b***h dangled this little baby’s foreskin in midair and playfully asked, “Anybody care to go fishing?”

My tongue lodged in my throat.

I felt like I was about to vomit.

I restrained myself. It was now my duty to take the infant back to the nursery for “observation.”

… Back in the newborn nursery, rather than observing, I cradled the infant. I held him and whispered comforting words as if he were my own. I’ll never forget those new little eyes watch me amid his haze. He knew I cared about him. He knew he was safe in my arms. He knew that I was going to take him to his mommy. But, deep in his little heart, at some level, I know he wondered where his mommy was. While he lay there mutilated in a level of agony that we cannot imagine, in what was supposed to be a safe and welcoming environment after his birth, where was his mommy?

Related: Religious Reasons Not To Circumcise

Betty, RN

We are saying what is happening, because the male myth is, “Well, I was circumcised and I am fine, and my son was circumcised and he’s fine.”

But we’re saying, “Maybe you were circumcised, but it wasn’t fine, because we were there, and we saw what happened. It’s the same thing with your baby. We were there, and we saw it. It was not fine.”

… That is the next step, for the grown men to come forward. It’s happening now. There is a powerful coalition forming. We women are coming out as mothers and as witnesses to this brutal sexual assault. Women who have been circumcised in Africa are coming forward, too. We’re all saying this isn’t okay.

Mary, RN

We just wanted people to stop hurting babies. In 1992, we started a petition. Before that, I think we all had the sense that something was wrong, but we had never communicated about it. Everything I’d read said circumcision isn’t a necessary thing to do, from a medical or health standpoint. So why are we doing it? You take a newborn baby, strap him down to a board, and cut on him. It’s obviously painful!

Circumcision became so intolerable that five of us wrote a letter saying that ethically we could no longer assist. When we were getting ready to present the letter, other nurses came out of the woodwork and asked to sign it. Out of about 50 nurses, 24 signed it.

Now we’re conscientious objectors, but it’s still going on. We can still hear it.

… Behind closed doors, you can hear the baby screaming. You know exactly what part of the operation is happening by how the screams are.

Mary-Rose, RN

My dreams were about taking the babies and strapping them down, participating in the whole thing, and having the babies say to me, “Why are you doing this? You were just welcoming me, and now you’re torturing me. Why, why, why?”

I’ve watched doctors taking more foreskin than they should. When there’s too much bleeding, they burn the wound with silver nitrate so that the penis looks like it’s been burned with a cigarette. Then the doctor will tell us to go tell the mother that this is what it’s supposed to look like.

Related: Celebrities Against Circumcision

Chris, RN

I worked with countless intact men, mostly European immigrants in Chicago: Poles, Serbs, Lithuanians, etc. Younger men and older men. Men who could walk to the bathroom and men who constantly soiled themselves. Men who had indwelling Foley catheters and men who didn’t. Men who were impeccably clean and men who were homeless. Men who were healthy and men who were critically ill and severely immunocompromised. Never once did I encounter an adult male patient who had ever had a medical problem due to being intact.

… In fact, female patients are far more prone to fungal and bacterial genitourinary infections than male patients are—yeast infections, urinary tract infections, abscesses, etc. And we know that this is largely due not only to their shorter urethra, but also to their labial folds—their “excess” skin. Why don’t we cut that off? Why isn’t female circumcision considered for infection prophylaxis? That’s how we think of male circumcision. Except the reality is that, as with male patients, the “benefit” of circumcision would be negligible, because the number of serious complications with women staying “uncircumcised” is extremely minor.

So as it stands, we have two sons who are intact. One is almost five years old and the other is nearly three. They’ve never had a problem. During diapering they required less care and bother than our daughters did. And now, during bathing, we don’t retract or mess with their prepuce (foreskin).

They’re clean. They’re fine.

I suspect that someday they’ll be like my patients were: ninety years old and intact—with no regrets.

Related: Circumcision, the Primal Cut – A Human Rights Violation

Patricia, RN

I am a neonatal nurse practitioner with over 42 years of experience in maternal newborn health. I have seen many circumcisions, and I have been appalled at the pain that they have caused.

… In my experience as a neonatal nurse, I know that circumcisions are painful, that little boys will cry for days after the procedure. They need to be medicated with Tylenol. They need to have injections at the penile nerve to try to prevent the pain, but it doesn’t completely eliminate it. I have seen excessive bleeding after the procedure. I’ve seen disfigurement. I believe that little boys are made the way they are because it’s absolutely fine to be intact. If there was a problem with foreskin, nature would not have put it there. So let little boys decide when and if they want to be circumcised. But parents, please spare your child the pain and unnecessary surgery that is not without risk. Just think about it.

I have seen, not loss of the entire penis but definitely disfigurement, and definitely excessive bleeding that has required intervention by GU specialists, suturing. Complications occur frequently.

…When babies are born, one of the first developmental tasks is to learn to trust the world, which means being in the comforting arms of their mother and father. To subject them in the first couple of days after birth to this terribly painful procedure just seems like the wrong way to start life. But the bottom line is: it is not necessary.

Jacqueline Maire, RN

I am a retired nurse in France as well as in British Columbia, a mother, a grandmother, and today I really want to speak specifically to female circumcisers, those who cut the penis of little boys. I have questions. What is your excuse? Were you at one point molested by a male in your youth that makes you now take revenge on any penis whatsoever and whatever the age of the victim, in this case, a defenseless little boy? Did you ever have an orgasm? And I’m not talking while you’re making love, I’m just talking about sex. Never had an orgasm with an intact male and discovered the wonders and the perfection of the act? Well. I feel sorry for you, but this is not an excuse to take revenge on defenseless children, baby boys mostly and I don’t understand how you can do that without being ashamed of yourself. Well, it’s just excuses, or medical excuses, or plain and simple fallacies. I feel sorry for you, but I also feel ashamed in the name of womanhood. You don’t respect your Hippocratic oath if you even know what it’s all about. Well, I’ll remind you it’s first “do no harm.” You’re just plain bitches, and I’m not insulting the female dog there. You are very mean, and I’m disgusted.

Related: 10 Circumcision Myths – Let’s Get the Facts Straight

Dolores Sangiuliano, RN

I’m a registered nurse, and we have an ethical code, the AMA Code of Ethics for Nurses, and it states very clearly that we are charged with the duty to protect our vulnerable patients. If we’re not protecting our vulnerable patients, then our license isn’t worth the paper it’s written on. If anybody is vulnerable, it’s a newborn baby. You know, a child with no voice, and that’s why I carry this sign: “I will not do anything evil or malicious and I will not knowingly… assist in malpractice”.

Infant circumcision is maleficence and malpractice. It’s totally unethical. Proxy consent is only valid for a procedure. In other words, parents can give consent for a procedure for their child. That’s proxy consent in a case of treatment or diagnosis, and circumcision is neither. You’re not treating a disease, and you’re not trying to diagnose an illness. So it just flies in the face of everything we know to be ethical, right, and moral. And I believe that forced genital cutting, all forced genital cutting, is always wrong. It should be consented to, fully informed consent, and that fully informed consent needs to include what you’re cutting off the penis, the value of the foreskin, and the consequences of changing the structure from a mobile, fluid unit to this dowel like structure, and that needs to be included. Ethical nurses educate their patients. Ethical nurses teach intact care, and ethical nurses don’t participate in forced genital cutting ever.

A woman from Egypt came up to us and she said,” I totally agree with you. Female circumcision happens in our country all the time, and it’s illegal but it still goes on. And it’s our cultural shame.” And she said, “I totally understand you having your cultural shame for doing this and it is the same thing.” And we just had a total agreement conversation about, and it doesn’t matter the varying degrees. We don’t need to compare the varying degrees of harm. Because a lot of people say female circumcision is much worse. But right out of her mouth she said, “But no, it’s the same. To the person having it done, it’s the same.” That was really good.

A Danish woman came and said, during her college days, she came to the United States and had a little bit of fun one season and she had sex with an American man. She was horrified because she didn’t know what had happened to him. She thought he had been in some sort of industrial accident. She didn’t know how to ask him or how to approach it. So that was an interesting tale, and I really appreciated the term industrial accident in a new way cause this is an industry, the medical industry. It’s not so accidental. Although their intention is to say that they’ve improved our males, they, perhaps by accident, devastated us and devastated so many men sexually and in their souls.

Kira Antinuk RN

Feminism, at its best, encourages me to think broadly and critically about the potentially harmful effects of gender constructions on all people. To me, feminism should be more than a narrow interest group of women who care only about women’s issues or women’s rights. My feminism is bigger than that. I believe that feminism can help us to identify and challenge discourses and practices that engender all of us.

… Upon review in 2009, scholars Marie Fox and Michael Thompson found that most feminists’ considerations of female genital cutting either omit to consider male genital cutting altogether or deem it a matter of little ethical or legal concern. Why might this be? So biomedical ethicist Dena Davis observed that the very use of the term “circumcision” carries vaguely medical connotations and serves to normalize the practice of male genital cutting.

Conversely, it’s worth noting, how the term female circumcision was essentially erased from academic, legal, and to some extent popular discourse following the World Health Organization’s re-designation of the practice as FGM or female genital mutilation in 1990. The WHO’s justification was that the new terminology carried stronger moral weight. So, terminology then, as well as the differential constructions of the practices themselves seems to protect male genital cutting from the critical scrutiny that other practices like female genital cutting attract.

Now it seems pretty clear to me, that this asymmetry extends to the very different understandings of genitalia and human tissue that we all have. Here in the West, for example, we’re heavily invested in the clitoris to the extent, that its excision results in what Canadian anthropologist Janice Body referred to as “serious personal diminishment.” Janice Body went on to say, “We customarily amputate babies’ foreskins, not with some controversy, but little alarm. Yet global censure of these practices is scarcely comparable to that level of female circumcision. Is it because these excisions are performed on boys and only girls and women figure as victims in our cultural lexicon?”

Sophia Murdock, RN

After we had taken the newborn back to the “circ room” in the nursery, I watched the nurse gather the necessary supplies, place him on a plastic board [a circumstraint], and secure his arms and legs with Velcro straps. He started crying as his tiny and delicate body was positioned onto the board, and I instantly felt uncomfortable and disturbed seeing this helpless newborn with his limbs extended in such an unnatural position, against his will. My instincts wanted to unstrap him, pick him up, and comfort and protect him. I felt an intense sensation of apprehension and dread about what would be done to him. When the doctor entered the room, my body froze, my stomach dropped, and my chest tightened.

This precious baby was an actual person. He was a 2-day-old boy named Landon, but the doctor barely acknowledged him before administering an injection of lidocaine into his penis.

Instantly, Landon began to let out a horrifying cry. It was a sound that is not normally ever heard in nature because this trauma is so far outside of the normal range of experiences and expectations for a newborn.

The doctor, perhaps sensing how horrified I was, tried to assure me that the baby was crying because he didn’t like being strapped onto the board. He began the circumcision procedure right away, barely giving the anesthetic any time to take effect.

Landon’s cries became even more intense, something I hadn’t imagined was possible. It seemed as if his lungs were unable to keep up with his screams and desperate attempts to maintain his respirations.

Seeing how nonchalant everyone in the room was about Landon’s obvious distress was one of the most chilling and harrowing things I had ever witnessed. I honestly don’t remember the actual procedure, even though the doctor was explaining it to me. I can’t recall a word he said during or after because I wasn’t able to focus on anything but Landon’s screams and why no one seemed to care. I only remember that the nurse attempted to give him a pacifier with glucose/fructose at some point.

Landon was “sleeping” by the end of the circumcision, but I knew it was from exhaustion and defeat. I had watched as his fragile, desperate, and immobilized body struggled and resisted until it couldn’t do so anymore and gave up.

Seeing this happen made me feel completely sick to my stomach, and I told myself that I would absolutely refuse to watch another circumcision if the opportunity presented itself again. I was unable to stop thinking about what I saw and heard…

The sounds that I heard come from Landon as he screamed and cried out still haunt me to this day.

Darlene Owen, RN

The truth about circumcision is that it is not medically necessary. It is not cleaner. Studies have proven again and again that it has no direct relation on cancer etc. as was once thought. It is also a very painful procedure. The baby does feel it, experience it.

There have been studies that demonstrate actual MRI changes within an infant’s brain after a circumcision has been performed.

As for those who claim “it looks better”, my response is, “Really? Based on whose decision?” A penis with a foreskin is how the penis is supposed to look. The foreskin has a function. It provides protection of the very sensitive glans (head) of the penis, and it provides ease during intercourse. During intercourse, the penis moves within its foreskin, preventing rubbing or friction of the vagina, which makes intercourse far more pleasurable for both the man and woman.

Many people will respond in outrage over female circumcision, yet still consider circumcision of males “the norm.”

Many parents aren’t properly informed of the procedure. It IS a very serious procedure with very many real risks involved. In my experience as a post-partum nurse, many parents who were led to believe it was a “minor” procedure and observed their sons’ circumcision, were sickened just as I was at the actual pain and distress it caused their infant. I have had many patients who, after witnessing their first son’s circumcision, decided immediately that they would not get any other boys they may have circumcised. Many parents told me that they wished they had known just how painful it would be for their son, that they would not have even considered it if they had known what is actually involved.

As for the argument that many men want their son to look like them, my answer is, “Why?” It is a stupid argument. Why can’t parents simply teach their son that their son’s penis is “normal and healthy”, that “Daddy had his normal, healthy functioning skin of his penis removed surgically, unnecessarily.” I also always say to those people, “Really? Well, watch an actual circumcision, and see if you still feel that way afterwards.” I have yet to see any parent watch a video, or view an actual circumcision procedure, who is not completely against the idea afterwards.

An uncircumcised penis is very easy to keep clean. There is no special care required. The saying goes, “Clean only what is seen.”

As for worrying about the son’s foreskin not retracting, and needing a circumcision later in life, that actually only occurs in a very, very small number of males. However, even if the male does need the surgery later in life, he will be put to sleep for the procedure and will not feel it. He will also be managed comfortably with pain medication. A newborn doesn’t have any of those benefits. A newborn is awake for it, will feel it, and doesn’t receive any pain medication.

Ask any grown male if he’d get his penis circumcised while awake, with no freezing, and I guarantee you’d hear a very loud resounding “NO!” Yet, many men will put their newborn son through it. Doesn’t make much sense does it?

I realize that at one time it was considered the norm. Now, however, with all of the education about it, I cannot understand why parents still proceed to put their tiny little newborn son through such a horrific experience.

I am proud to say that I am an intactivist and the proud mom of two gorgeous, healthy, intact boys.

Related: Doctors Against Vaccines – Hear From Those Who Have Done the Research

Andrew, RN

I am a registered nurse. I work at a DC hospital. It’s not part of my current job, but when I was in nursing school, I witnessed several circumcisions as part of my rotation, and I was interested in it because personally, I had developed an opposition to circumcision.

As an adult, I never had to be part of that decision not having a child. But I knew that if I did, it was one that I would want to make. And when I had the opportunity, I asked a doctor whom I watched perform it if he thought it was medically necessary because in my education, it is no longer stated, there is no longer a valid medical claim being made in the literature including in my nursing textbooks and so how can you justify it? And he said that he doesn’t personally justify it. He just knows that for the time being, it will continue to be done and he wants it done humanely and as well as possible. And he said “And I do it well” And indeed, he seemed to be proficient in it. I then asked him if he had noticed that the husband of the couple who had just had it done had seemed like he had his doubts and he said, “Yeah, I noticed that too”. “Do you think someone should have discussed it further with him because he clearly didn’t support the decision.” And then he said that that happens all the time, that one of the two of the couple want that decision made and the other go along with it.

My nurse’s perspective is that part of our job as an educator is to give more information, and so that would have been a great opportunity for someone to give that couple more information about whatever concerns the mother had that made her think that circumcision was the best decision. She seemed actually like she had some ill-conceived notions about the difficulty of keeping it clean, things that I knew that medically were not actually accurate. I actually thought at that time that I saw an opportunity for nurses to step in and educate her, to help and not tell the couple what they should do, but make sure they had the best information possible to make a decision, that again, is no longer being promoted clearly on the literature as medically necessary, including in my textbooks, and this was just last year.

Carole Alley, RN

And after the strap down and tie, they’re still screaming. The screaming lasts the entire time. And I don’t know if you’ve ever heard a baby scream like that. It’s not a regular cry. It’s not a cry of hunger or a cry of wanting to be hugged or a cry of having a wet diaper. This is a cry of incredible pain. I mean, it goes right through your body. Every cell in your body responds. And then the child is circumcised. You know, there are two different ways of doing it. Sometimes anesthesia local will be used but for the most part, I’ve never seen babies stop crying, even if that’s given. A lot of the time, it’s not used. More often than not, it’s not used. And then the clamp goes over the baby’s penis and the foreskin is cut off.

Patricia Worth, RN

In my opinion, this is an abuse. There is not enough information out there to convince me that this is medically necessary. And just as I can read through the Old Testament of the Bible, and stoning women to death because they committed adultery, I see as abusive, this “ancient covenant,” I look at it as a well, the human race has done all kinds of things and thought was the best thing at the time, and in retrospect, we can look back and go, blood sacrifice of human beings? This is not right. This is not morally right. This is not ethical. And especially when you’re taking someone who has not consented. Parents can consent all they want. This does not mean the child has consented to this.

Marilyn Milos, RN The Mother of the Intactivist Movement

While working as a nurse in a hospital, she learned about circumcision by assisting doctors during the procedure. The obvious pain and distress felt by the infant prompted Marilyn to research circumcision. Afterwards, she was able to provide parents with all of the facts.

By offering true informed consent, she dramatically cut into her hospitals’ cutting business. She was fired. Undaunted, she went to work saving our sons. She founded a non-profit known as NOCIRC, demonstrating that one person can still make a difference.

Here are her words:

The more we understand what was taken, the more we understand the harm of circumcision, that it is a primal wound, that it does interfere with the maternal-infant bond, that it disturbs breastfeeding and normal sleep patterns. Most importantly, that it undermines the first developmental task, which is to establish trust. And how can that male ever trust again? And I think that’s very hard for a lot of men and why men need to have control and be in control, and their reactions to make themselves more safe.

It was so amazing to me when I worked in a hospital, and my first question would be, “I see—I see that you’re gonna have the baby circumcised, and may I ask why you’ve chosen circumcision for your baby?” And they would say, “Oh, because I’m a Christian.” And I said, “Do you know that there’s 120 references to circumcision in the New Testament, that circumcision is of no value? If you’re a Christian you don’t live by outward signs. You live by faith expressed through love. Christ shed the last—was the last to shed the blood. He was the ultimate blood sacrifice for everybody. We don’t need to do this again.”

Conclusion

The hardest moral dilemmas seem to lie at the crossroads of two or more moral principles. In this instance, the right to religious freedom and the right to bodily integrity are in conflict for some parents. But if we are to uphold the right to bodily integrity for girls regardless of religion (Muslims often circumcise girls), shouldn’t we allow the same protection for boys?

Although religion is a factor, many parents choose circumcision simply because it is considered the norm. Myths about disease and cleanliness add to the confusion. When parents are not given all the facts, they cannot make an informed decision. On average, nurses are poorly equipped to answer their questions about circumcision. They do not educate parents, explaining the 16 functions of the foreskin or teach parents how to care for an intact child. (Nothing! Do not retract the foreskin. It cleans itself!)

Our sons’ genitals are carved apart in the name of healthcare when in actuality the practice is a profit-making enterprise. Circumcisions generate a lot of money for hospitals, while intact penises bring in no money at all. So while it is ethical for a nurse to provide parents with informed consent, it is wholly unprofitable for them to do so.

The truth will win. Circumcision is a profound violation of human rights. This conclusion is inescapable once we begin to think critically about the practice.

Author’s Note:

Male genital mutilation is still legal in all 50 states, and although Marilyn Milos hasn’t yet completely changed the world, she changed mine.

I am the second born of two sons. My older brother was circumcised. I was not.

Before my birth, my mother met a neighbor who had been given literature from NOCIRC. The sharing of this information about the benefits of the foreskin and the dangers and drawbacks of circumcision is the reason I was left intact.

Marilyn Milos bet on the idea that when given all the facts, more parents would make the right decision, and in my case she was spot on. I am intact, my sons are intact, and my nephews are intact.

Marilyn, I can never thank you enough for what you’ve done for me and for my family. You are an inspiration to us all.

Sources

Circumcision- A Male RN’s Perspective: Chris – Dr.Momma.org

Ethical Nurse Refuses to Assist Infant Circumcision: Dolores Sanguiliano – YouTube

Nurses For the Rights of the Child

Nurse Questions Women Who Sexually Mutilate Boys: Jacqueline Maire – YouTube

Registered Nurse Shares Thoughts About Circumcision: Andrew – YouTube

Nurses Against Circumcision was originally published on Organic Lifestyle Magazine

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shadows of doubt 90 day fiance

There are other costs to consider, too, like a deposit and furniture, he reminds her.September 4, 10:01 pm Spoiler Alert ’90 Day Fiancé: Happily Ever After?’ Recap: Big Ed and Liz vs. whilst Mohamed is introduced to the rest of Danielle's family. Danny manages to miss Amy's first day in the U.S. She loves the first apartment they go to see, but they can’t afford it, not while they only have his salary. ( ) Justin manages to surprise his relatives with the news of his engagement whilst Daya meets Brett's daughter. Julia’s dream of moving off Brandon’s parents’ farm may be close to becoming a reality … or not. and he may be scamming her.) Once he goes through what would happen if she moves forward with her plans – namely that they’d have to restart the spousal visa process if they get back together, and it would raise flags with immigration – she begins reconsidering. (He also does admit that he thinks some of Michael’s motivation is to get to the U.S. He points out all the time, money, and emotions she’s invested, but she’s wondering if she made a mistake. Meanwhile, Angela goes to see her lawyer, Lew, and tells him she wants a divorce. (“Finally,” Ade says.) While Michael still loves Angela, he wants things to change (including that he’s part of making decisions from now on). Will either Angela or Michael fight for their relationship after it sounded like they broke up? Well, his friends are pretty much ready to celebrate when he informs them of their latest fight. They drive her to her new home, 45 minutes away from New Orleans (which Gwen knows will be an adjustment for her son), in a family-oriented, quieter area. She takes the opportunity to choose somewhere she likes and will feel safe with their baby daughter (namely, outside of the city).Īnd while Jovi may not be home to help his wife, his mother and grandmother do help her pack up (and do most of it, it seems) the day of the move. Not only is he going to miss Christmas (he’s due home a day after), but this also means that Yara has to handle moving out of their current place and finding a new one on her own. Yara’s two weeks COVID-free (and staying with her mother-in-law Gwen) when Jovi delivers some bad news: he won’t be home for a few more weeks. He doesn’t like that she doesn’t tell him things, while she sees her health as the priority. She feels alone, she says, while he disagrees: she’s fine and he takes care of her. She tells him her doctor scheduled it, not her, but this all goes back to a big problem between them: their lack of communication. He takes it in stride during the dinner, just telling her to let him know which day so he can take off.īut once they’re home, he admits that it threw him that she left him out when she set up the appointment. In fact, she waits to inform him until they’re having dinner with her friend, Juliana, because she knows he’ll be mad (for scheduling it without talking to him and the cost). Things remain tense between Natalie and Mike following their fight regarding his mom (and what may or may not have been said), and it gets worse when she tells him her surgery on her nose has already been scheduled. Elizabeth is understandably upset as they get back on the road. (The only thing everyone can agree on? They’re never doing this again.) The next morning, when Andrei is supposed to be watching their daughter, Elizabeth catches her falling backward on the stairs. The next problem comes after they stay in an Airbnb for the night. Elizabeth pushes Chuck to talk to them, and he pretty much reiterates he doesn’t want to talk business on the trip. She feels like he has a secret agenda when it comes to her father Chuck, while he thinks she’s a drama queen. When he wonders what it means for their future (and his in the U.S.) if she doesn’t like what she sees from him, she says that’s a conversation for another day.Īndrei and his sister-in-law Becky’s conversation on the side of the road during the family trip in the RV just rehashes everything that’s already been said. However, he argues that being a parent is new for him and wants time to figure everything out. If he doesn’t help her for real, she’s not sure if they’ll be here for the holidays, she warns. He follows, and their conversation once again turns to how long she’s staying. but did when she made the trip to join him in South Africa.Īnd after a fight about changing diapers, she walks outside. In fact, she thinks it might be worse since she doesn’t expect to have help in the U.S. She reminds him they’re not there that long, and he insists, “There’s no time frame.”īack at his place, Tiffany becomes frustrated when she wants to relax but Ronald can’t handle watching the kids and putting away the food at the same time (which she does at home). They also once again disagree on how long Tiffany and the kids are staying when she notices how much cereal he’s bought.

0 notes

Text

The Black Mortality Gap, and a Document Written in 1910

Some clues on why health care fails Black Americans can be found in the Flexner Report

— By Anna Flagg | August 30, 2021

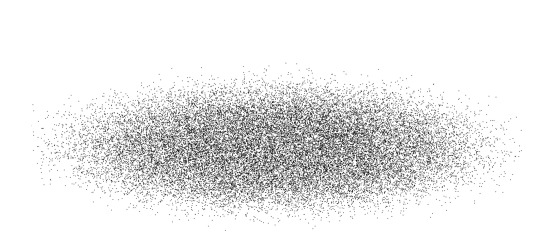

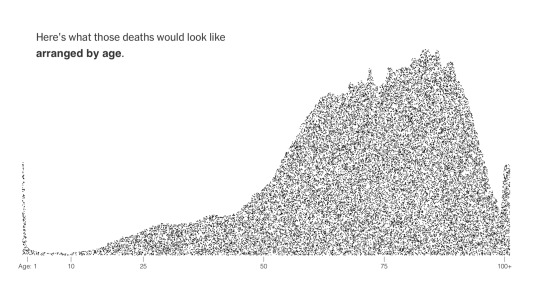

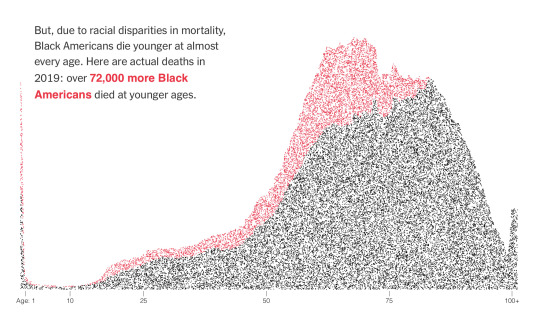

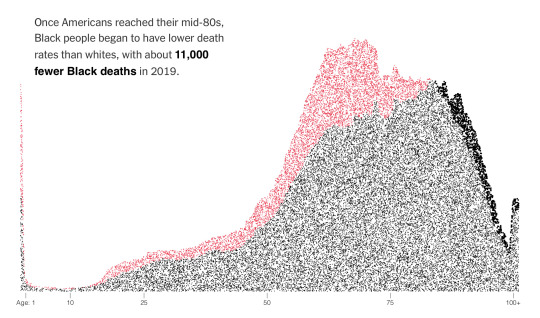

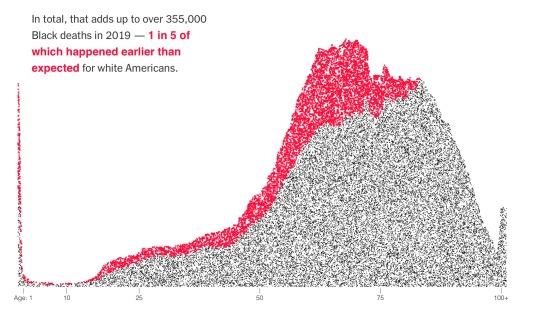

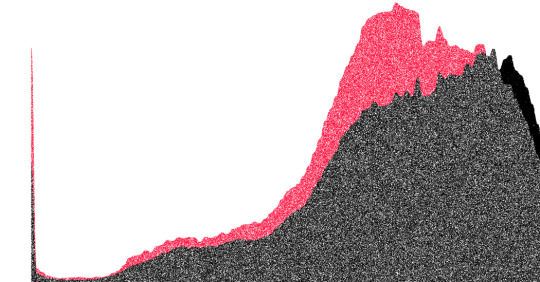

If Black Americans died at the same rates as white Americans, about 294,000 Black Americans would have died in 2019. Each dot represents 10 people

Black Americans die at higher rates than white Americans at nearly every age.

In 2019, the most recent year with available mortality data, there were about 62,000 such earlier deaths — or one out of every five African American deaths.

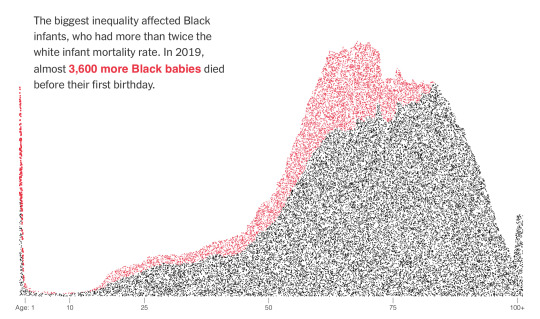

The age group most affected by the inequality was infants. Black babies were more than twice as likely as white babies to die before their first birthday.

The overall mortality disparity has existed for centuries. Racism drives some of the key social determinants of health, like lower levels of income and generational wealth; less access to healthy food, water and public spaces; environmental damage; overpolicing and disproportionate incarceration; and the stresses of prolonged discrimination.

But the health care system also plays a part in this disparity.

Research shows Black Americans receive less and lower-quality care for conditions like cancer, heart problems, pneumonia, pain management, prenatal and maternal health, and overall preventive health. During the pandemic, this racial longevity gap seemed to grow again after narrowing in recent years.

Some clues to why health care is failing African Americans can be found in a document written over 100 years ago: the Flexner Report.

In the early 1900s, the U.S. medical field was in disarray. Churning students through short academic terms with inadequate clinical facilities, medical schools were flooding the field with unqualified doctors — and pocketing the tuition fees. Dangerous quacks and con artists flourished.

Physicians led by the American Medical Association (A.M.A.) were pushing for reform. Abraham Flexner, an educator, was chosen to perform a nationwide survey of the state of medical schools.

He did not like what he saw.

Published in 1910, the Flexner Report blasted the unregulated state of medical education, urging professional standards to produce a force of “fewer and better doctors.”

Flexner recommended raising students’ pre-medical entry requirements and academic terms. Medical schools should partner with hospitals, invest more in faculty and facilities, and adopt Northern city training models. States should bolster regulation. Specialties should expand. Medicine should be based on science.

The effects were remarkable. As state boards enforced the standards, more than half the medical schools in the U.S. and Canada closed, and the numbers of practices and physicians plummeted.

The new rules brought advances to doctors across the country, giving the field a new level of scientific rigor and protections for patients.

But there was also a lesser-known side of the Flexner Report.

Black Americans already had an inferior experience with the health system. Black patients received segregated care; Black medical students were excluded from training programs; Black physicians lacked resources for their practices. Handing down exacting new standards without the means to put them into effect, the Flexner report was devastating for Black medicine.

Of the seven Black medical schools that existed at the time, only two — Howard and Meharry — remained for Black applicants, who were barred from historically white institutions.

The new requirements for students, in particular the higher tuition fees prompted by the upgraded medical school standards, also meant those with wealth and resources were overwhelmingly more likely to get in than those without.

The report recommended that Black doctors see only Black patients, and that they should focus on areas like hygiene, calling it “dangerous” for them to specialize in other parts of the profession. Flexner said the white medical field should offer Black patients care as a moral imperative, but also because it was necessary to prevent them from transmitting diseases to white people. Integration, seen as medically dangerous, was out of the question.

The effect was to narrow the medical field both in total numbers of doctors, and the racial and class diversity within their ranks.

When the report was published, physicians led by the A.M.A. had already been organizing to make the field more exclusive. The report’s new professional requirements, developed with guidance from the A.M.A.’s education council, strengthened those efforts under the banner of improvement.

Elite white physicians now faced less competition from doctors offering lower prices or free care. They could exclude those they felt lowered the profession’s social status, including working-class or poor people, women, rural Southerners, immigrants and Black people.

And so emerged a vision of an ideal doctor: a wealthy white man from a Northern city. Control of the medical field was in the hands of these doctors, with professional and cultural mechanisms to limit others.

To a large degree, the Flexner standards continue to influence American medicine today.

The medical establishment didn’t follow all of the report’s recommendations, however.

The Flexner Report noted that preventing health problems in the broader community better served the public than the more profitable business of treating an individual patient.

“The overwhelming importance of preventive medicine, sanitation, and public health indicates that in modern life the medical profession” is not a business “to be exploited by individuals,” it said.

But in the century since, the A.M.A. and allied groups have mostly defended their member physicians’ interests, often opposing publicly funded programs that could harm their earnings.

Across the health system, the typically lower priority given to public health disproportionately affects Black Americans.

Lower reimbursement rates discourage doctors from accepting Medicaid patients. Twelve states, largely in the South, have not expanded Medicaid as part of the Affordable Care Act.

Specialists like plastic surgeons or orthopedists far out-earn pediatricians and family, public health and preventive doctors — those who deal with heart disease, diabetes, hypertension and other conditions that disproportionately kill Black people.

With Americans able to access varying levels of care based on what resources they have, Black doctors say many patients are still, in effect, segregated.

The trans-Atlantic slave trade began a tormented relationship with Western medicine and a health disadvantage for Black Americans that has never been corrected, first termed the “slave health deficit” by the doctor and medical historian Dr. W. Michael Byrd.

Dr. Byrd, born in 1943 in Galveston, Texas, grew up hearing about the pain of slavery from his great-grandmother, who was emancipated as a young girl. Slavery’s disastrous effects on Black health were clear. But by the time he became a medical student, those days were long past — why was he still seeing so many African Americans dying?

Dr. Linda A. Clayton had the same question.