#Aliénor d'Aquitaine

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Aliénor d'Aquitaine (1122-1204).

#Capetian dynasty#reine des francs#vive la reine#aliénor d'aquitaine#duchesse d'aquitaine#Duchesse de Normandie#comtesse d'Anjou#maison de poitiers#eléonore d'aquitaine#reine d'angleterre#full length portrait#reine de france#royaume de france#duché d'aquitaine#eleanor of aquitaine#duchess of aquitaine#kingdom of england#kingdom of france#queen consort#full-length portrait

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

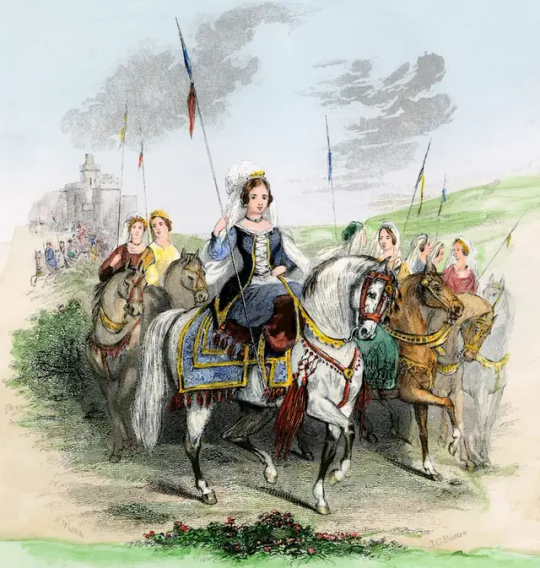

Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine (1124-1204). American school.

#engravings#eleanor of aquitaine#queen of france#vive la reine#queen of england#god save the queen#duchess of aquitaine#crusades#crusader#Aliénor d'Aquitaine#Éléonore d'Aquitaine#Alienòr d'Aquitània#House of Poitiers#maison de poitiers#Ramnulfids#duchy of aquitaine#duchy of gascony#queen consort#eleonore de guyenne#on horseback#equestrian portrait

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Petites histoires du monde

Une compilation de plusieurs petites histoires sur la Grande Histoire avec comme héros : Baudouin IV de Jérusalem, Édouard Ier, Bohémond d'Antioche et d'autres souverains et souveraines.

#baldwin iv#ao3 fanfic#king edward I#bohemond i of antioch#Raymond VII de Toulouse#Aliénor d'Aquitaine#Louis VII de Frane

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Capétiens vs Plantagenêts: a matter of suzerainty.

It was also his position as suzerain which gave Louis VII the chance of interfering in and inflaming the quarrels which raged in the Angevin family. This was an effective means of weakening his great antagonist. Henry II and Eleanor produced a large family, and reared four of their sons to the age at which custom demanded that they should be provided for. Their eldest son Henry was granted Normandy in October 1160 and was associated with his father on the throne of England in 1170. Richard was given Aquitaine in 1169 and Geoffrey Brittany in 1175. John, the youngest child of Henry and Eleanor, was not old enough to be entrusted with any estates until the very last years of his father's reign, and by the time he came of age all the available lands had been given away. As Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Count of Poitiers, the sons of Henry II came to perform homage to the King of France and became his men. It was in vain that Henry II sought to utilise the Norman procedure of pariage to maintain the unity of his continental territories in favour of his eldest son, the "Young King" Henry. (Under pariage the eldest son succeeded to all the heritable property and was alone answerable for it to the suzerain; each of his brothers received a share, but held it of him). This device could not be put into full operation in Aquitaine, which was not part of Henry's heritage but Eleanor's. And when she granted it to Richard, he owed homage not to his father or his eldest brother, but to the King of France. The Young King Henry had done homage as Duke of Normandy to Louis VII in October 1160. When he repeated his homage in 1170 it was made to embrace Anjou, Maine, and Brittany as well. At the same time Richard did homage to Louis for Aquitaine.

It is true that in 1174 Henry II compelled his sons to perform homage to him after their rebellion, but this new homage did not necessarily annul their homages to the King of France. Henry II himself had done homage to Louis VII in 1151 and again in 1169, and was to perform it yet again to Louis's successor, Philip Augustus, in 1180. Thus throughout the conflict between Louis VII and Henry II the French king's suzerainty was affirmed and recognised. This did not save Louis from defeats at his vassal's hands. Nevertheless, to judge from the Toulouse affair in 1159, Louis' suzerainty occasionally cramped Henry's style, and put him in the wrong in the eyes of contemporaries, including the barons of his continental fiefs. To play the rebel vassal was hardly prudent for a king when many of his own vassals were rebelliously inclined. It was not that the idea of rebellion itself shocked feudal society. On the contrary, it was one of the legitimate courses open to a vassal needing to safeguard his rights against the encroachments of his suzerain. But in the disputes between Louis VII and Henry II, Henry was the law-breaker as well as the vassal in revolt. For his rebelliousness against an impeccable suzerain there could be no justification.

It may be objected that Louis VII was constantly intriguing with Eleanor of Aquitaine and with Henry II's sons. But after all Eleanor, as Duchess of Aquitaine, was herself a royal vassal. Two of Henry's sons had done homage to Louis. Another, Geoffrey, by dint of his father's vassalage, was the French king's rear-vassal. And the king had, as suzerain, not merely the right but the duty to concern himself with the welfare and harmony of his great vassal's family, to ensure that a proper settlement was made on the sons. It would be unfair to accuse Louis of hypocrisy; nor did Henry ever complain that the French king was making trouble in his family. Louis' own grievances against Henry were many and varied, and Henry never made a serious effort to deny their validity.

Thus from 1154 to 1180 Henry II had the appearance of a vassal engaged in unjustifiable revolt against his suzerain. This line of conduct undermined his own position. It constantly reminded the baronage of the Angevin fiefs that the King of France was Henry's suzerain- if only because his suzerainty was so often invoked. And it helped to prevent the fusion of the individual elements of the Angevin empire on the continent. Provincial separation, already too strong for Angevin rule to subdue, was reinforced.

Robert Fawtier- The Capetian Kings of France

#xii#robert fawtier#the capetian kings of france#louis vii#henry ii of england#aliénor d'aquitaine#henry the young king#richard the lionheart#geoffrey plantagenêt#john lackland#jean sans terre

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Names for fem!Alastor

I've seen people use "Alastoria", or common given names that start with Al like Alice, but there are so many other options! For example:

Alastor. Who says it can't be unisex?

Aliénor. It was the name of several queens and nobles in the Middle Ages - such as Aliénor d'Aquitaine. A queen's given name seems fitting for someone like her (Variants: Alienor, Eleanor... + Aénor/Aenor/Adénor, the name of Aliénor d'Aquitaine's mother)

Alecto. One of the Erinyes, a chtonic goddess of vengeance whose name means "endless anger". ("Alastor" was one of Zeus' epithets, but as a separate personification, he was the Erinyes' sidekick)

Astoria (I know, it's basically Alastoria without the "Al", but it's also a real name!)

Adrasta Greek goddess of inevitable fate and inescapable punishment

Electra/Elektra, mythological character who avenged her father by killing her mother (+ Electra complex... If Alastor has daddy issues maybe fem!Alastor could have mommy issues haha. Plus it sounds like electricity which creates a fun parallel with Vox whose name means "voice")

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Servant Matrix: RICHARD I

Class: Saber

True Name: Richard I, Richard the Lionheart

Gender: Male

Alignment: Lawful Neutral

Height/Weight: 178cm / 66kg

Source: Historical Fact

Region: Europe

ENDURANCE GAUGE: [X/X/X/X/X/X]

MANA CHARGES: [ X / X / X / X / X ]

COMMAND SPELLS: [ X | X | X ]

A lionhearted man, crusader, and King of England who lives more in accordance to his own emotions and ambitions rather than the orders of his superiors of a perceived 'status quo'. In life, he was said to possess a great many talents and excelled at almost everything. A man possessing a dangerous charisma who was lionized as a magnificent and ideal warrior king despite being absent for the majority of his reign. A crusader, a tyrant, a warlord, a knight-- a man who has held many titles and been viewed through many different lenses both during and after his life.

He was found by the Masters in a laboratory belonging to the Umbral Institute, presumably as part of a plot to create an 'exploitable Excalibur'. How he got there and what the details of the experiment are remain a mystery, though he is grateful to be brought back to the side of humanity. If he remained undiscovered and the plot was finished, could he have instead been a fierce enemy rather than a bravehearted ally…?

He and his siblings of the House of Plantagenet (known to historians also as the 'Devil's Brood') were known for their ferocity, constant infighting, and propensity for violence. Thankfully, as a Saber, his more personable traits come to light. In life, he was known for his eccentric and sporadic personality that earned him the nickname 'Oc e Non' (Yes and No), meaning that his line of thinking can be extreme and difficult to follow at times, but one does not earn the title 'Coeur de Lion' (Lionheart) from taking the simple path. He is a bold-hearted warrior king that will slay his enemies without a shift in his expression or a moment's hesitation-- and also his allies, if he finds them particularly disagreeable.

Despite not possessing an actual 'Charisma' skill, he does have a rather magnetic personality that makes him easily likable. That, in addition to his adoration of the heroes of old such as King Arthur and the Knights of the Round or Charlemagne and his Twelve Paladins thanks to being told stories by his mother Aliénor d'Aquitaine, means that even with the more troublesome aspects of his personality present, he strives to act in a manner that he considers honorable and knightly-- wishing to help the common folk, and finding the prospect of 'saving humanity' a noble and exciting path to follow.

To put it simply, he's a royal pain, but a royal pain that you'd rather have as an ally.

Strength: B

Endurance: B

Agility: EX (B -> A++)

Mana: B

Luck: C

NP: A

SKILLS:

Magic Resistance (B) - Cancel spells with a chant below three verses. Even if targeted by greater magecraft and Greater Rituals, it is difficult for them to be affected.

Riding (A) - All vehicles and all creatures but those of Phantasmal Beast and Divine Beast-rank can be used as mounts.

Godspeed (A) - A skill crystallizing his ferocity and speed on the battlefield and the extent of his marches. The longer the battle continues, the higher his Agility parameter climbs.

Lionheart (A) - A skill embodying the name 'Lionheart'. When he's present on the battlefield, enemies are inflicted with wariness and fear, and his allies are emboldened with an increase to morale.

All Kinds of Talents (A) - A skill based on anecdotes that proclaimed his talent at a great many things, ranging from combat to the arts. Anything he practiced while he was alive can be performed at 'B-Rank' or higher, and new skills can be picked up incredibly quickly.

NOBLE PHANTASM: Excalibur

The Sword of Forever Distant Victory.

They say that Richard I liked to name any sword that he uses 'Excalibur', due to his immense adoration of King Arthur.

This Noble Phantasm is not the true Excalibur as wielded by the likes of King Arthur, but a replica blade that can be created by Richard whenever he wields something that he wishes to consider 'Excalibur', ranging from a random tree branch to an ornamental sword. The strength of the attack depends on the 'value' of the object, with different objects resulting in a different energy release.

Despite the power of this Noble Phantasm, it will always pale in comparison to the true Excalibur.

NOBLE PHANTASM: Rounds of Lionheart

A mysterious ability to materialize those that he bonded with in life using his own Saint Graph as a catalyst. One of Richard's trump cards, and a skill that even someone as eccentric as himself does not take lightly, and a Noble Phantasm that he keeps close to his chest and doesn't speak of carelessly.

They manifest within Richard's shadow from the records of the Moon Cell. In other theoretical worlds, they would be directly summoned from the Throne of Heroes. They cannot fully manifest in a practical sense, and are weaker than normal Heroic Spirits, but can cover Richard's blind spots and provide him advice during combat.

The number of 'essences' he can summon is dependent on the amount of magical energy he possesses.

EXTRA SKILL: Fury Shift

A unique trigger possessed by Richard due to belonging to a multifaceted Master-- some of which that may have been more attuned to Richard's aspects as a 'warlord'. Richard can take 'Brave Actions', which have a higher chance of causing Richard harm, but increase his 'Heat'. When his 'Heat' is fully maxxed out, the Masters can temporarily shift him into a destructive state surrounded by raging flames-- a true manifestation of 'Lionheart'. Richard's Endurance Gauge will continuously decrease each action, however his destructive power increases immensely.

NOBLE PHANTASM: Utopie Purgatoire

The flames of purgatory burn in the shape of ferocious lions as Richard charges forth.

A violent, massively powerful manifestation of Richard the Lionheart's unreasonable fighting style, where he'd charge ahead of his soldiers-- and the destruction that he left in his wake.

Can only be used when 'Fury Shifted'

-

COMBO ATTACKS:

SWORD OF GILDED VICTORY

{REQUIRES: YOUNG GIL + RICHARD I, -3 MP EACH} --

Gil passes Richard a blade from the Age of Gods from his treasury, allowing him to use 'Excalibur' in a massively powered up fashion, unleashing a barrage of super-powered beams. The blade is destroyed once the technique is completed.

MYSTIC CODES:

'Wandering Rock and Roll'

A fashionable, modern outfit that RICHARD bought for himself. As of now, the change is purely cosmetic. However, there seems to be some latent potential within the clothing...

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

OUVRAGE | Aliénor d'Aquitaine, par Philippe Tourault ➽ https://tinyurl.com/Ouvrage-Alienor-Aquitaine Aliénor d'Aquitaine est une héroïne, une vraie. On ne compte plus les films, documentaires, biographies, romans ou encore bandes dessinées qui la mettent à l'honneur. Mais comment pourrait-il en être autrement avec un tel destin ?

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aliénor d'Aquitaine, née vers 1122 ou 1124, et morte à Poitiers le 31 mars ou le 1er avril 1204, a été tour à tour reine de France, puis reine d'Angleterre. Aliénor d'Aquitaine vécu 82 ans.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Katharine Hepburn et Peter O'Toole dans "Le Lion en Hiver" d'Anthony Harvey (1968) - d'après la pièce de théâtre éponyme de James Goldman (1966) évoquant les intrigues menées autour de la succession d'Henri II d'Angleterre (1133-1189) avec de son épouse Aliénor d'Aquitaine et leurs trois fils Richard Coeur de Lion", Jean Sans Terre et Geoffroy II de Bretagne - décembre 2023.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Note de lecture : La Femme au temps des cathédrales

Régine Pernoud est sans doute la plus grande médiéviste du XXème siècle. Contrairement à Georges Duby, elle aborde cette époque sans parti pris et avec une passion nettement plus chaude que ne le fait Jacques Le Goff, sans sacrifier néanmoins à une pesante érudition. Le Moyen-Âge est encore trop souvent abordé avec des lunettes déformantes qui ne font pas percevoir tout l'intérêt que présente cette période aux temps, toujours actuelles, où l'Occident se demande où il va, sans vraiment savoir d'où il vient. La thèse de l'autrice se résume à ceci : le Moyen-Âge a été une période d'émancipation de la Femme, et c'est la Renaissance, tant encensée pour son prétendu humanisme, qui a marqué un recul de la condition féminine.

Car il faut bien reconnaître que les racines chrétiennes de l'Occident, sans pour autant que cette expression ne nie d'aucune façon les apports orientaux, notamment ceux de l'Islâm, ont poussées dans le terreau fertile du sacrifice de ces premières chrétiennes, canonisées pour certaines, par l'institution ecclésiale. L'une échappe à la volonté autoritaire du rejeton barbare du pater familial romain pour vivre son chemin spirituel, l'autre fait plier le genou de son royal mari devant le Dieu vivant, une troisième, enfin, fonde à elle seule, une lignée spirituelle sous la forme déconcertante aujourd'hui d'un couvent. Mais si un personnage historique synthétise et irradie toutes les facettes de la féminité au Moyen-Âge, c'est bien Aliénor d'Aquitaine. Mère de onze enfants, épouse du Roi de France, puis du Roi d'Angleterre après avoir fait plier le Pape à son propre désir, véritable Dame inspiratrice des poètes, et poétesse elle-même, administratrice hors pair non seulement de ses biens propres, mais encore, de ceux de la Nation toute entière quand l'intérêt supérieur de cette dernière l'exige. Pas un gramme de la viridité d'Aliénor n'a été sacrifié sur l'autel de la raison d'État, montrant ainsi, par l'example, combien l'incompatibilité entre pouvoir et féminité, qu'on entend si souvent résonner au prétendu Grand Siècle, n'est pas fondée.

On dira peut-être que cela ne concerne que quelques femmes exceptionnelles et pas la majorité d'entre elles. Rappelons ici, à la suite de Mme Pernoud, que, dans l'institution médiévale du mariage, les femmes choisissent leur mari et que, dans le cadre de ce sacrement, le prêtre n'est qu'un témoin. Rappelons aussi que les femmes travaillent à leur propre bonheur, dans ce cadre ou dans un autre, et quand la femme est possédante de biens, elle n'est en rien une potiche sous l'autorité despotique de son mari ou une dominatrice, avide de concupiscence.

Et il nous faut bien en revenir aux raisons historiques du dénigrement systématique du Moyen-Âge. Le Siècle des Lumières, et le positivisme républicain à sa suite, ont du, pour effacer l'apport intellectuel de l'Église, produire un véritable arsenal de dénigrement de cette époque obscure. Nous ne nions certes pas que l'institution ecclésiastique ait pu commettre certains abus lors du sacrement de la confession, en nourrissant malicieusement la culpabilité des ouailles, mais il n'en demeure pas moins que ce sont bien les acquis intellectuels de l'Église qui étaient ainsi visées.

Un ouvrage salutaire donc, qui ne cède rien au détriment de l'exactitude historique ni de la plénitude de ce que fut la Femme aux temps des cathédrales.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louis VII:

First husband of Aliénor d'Aquitaine.

Philippe:

Won the Battle of Bouvines. Overall a pretty cool dude.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Liste de livres en Français :

Aliénor d'Aquitaine.

Ce n'est qu'un petit aperçu de la bibliographie qui concerne Aliénor d'Aquitaine. Demain, vous pourrez retrouver les livres en anglais.

Romans :

Pour l'Aliénor d'Aquitaine d'Elizabeth Chadwick, les romans sont en trois tomes.

Clara Dupont-Monod a aussi écrit:

Mireille Calmel à publié un cycle entier consacré à Aliénor et à son fils Richard. Il commence par le Lit d'Aliénor.

Roman jeune :

BD :

La série Les reines de Sang, Aliénor d'Aquitaine se compose de six livres.

Docs historiques :

#aliénor d'aquitaine#eleanor of aquitaine#plantagenet#medieval history#history medieval#histoire#france

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey there, I love your work ❤️

Just wanted to ask you which movie or series you used for your Aliénor d'Aquitaine gifs? Thank you in advance!

hi anon, thank you so much <3

I use multiple media for eleanor. mainly from the documentary ‘britains bloodiest dynasty/crown’, ‘robin hood (2010)’ and sometimes from the tv series ‘camelot (2011)’.

hope that helps :)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I gotta say I think it's infinitely funny Aliénor d'Aquitaine girlbossed the bases for the 100 year war because she was repudiated by the king of France. The guy blamed her for not giving him a daughter (the sex is determined by the spermatozoid btw), and she immediately remarried with the king of England, taking away a good chunk of Occitanie with her. And then she had a shit ton of sons. And she inherited even more land in France. And then one of her sons became king of Brittany. While it's not the starting point of the 100 year war and the whole thing is A LOT more complex than that I like to think that this entire chain of events made the relationship between the two countries fucked up enough that in a bit more than a century they just went at each other's throat so fucking hard in a way that wouldn't have happened without it. Because a guy was angy he couldn't produce a son after two attempts

0 notes

Text

Aliénor d'Aquitaine et les Plantagenêts, le temps des crépuscules : épisode • 4/4 du podcast Aliénor d'Aquitaine, une reine pour deux royaumes

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sur les traces du fabuleux trésor d'Aquitaine de Vanessa Pontet (Auteur), Artemisia (Illustrations)

Achat : https://amzn.to/3WNlGBi Sur les traces du trésor perdu d’Aliénor d’Aquitaine ! Chronique : “Sur les traces du fabuleux trésor d’Aquitaine” est un livre écrit par Vanessa Pontet et illustré par Artemisia. L’histoire suit Faustine, une passionnée d’histoire et de trésors, qui décide de suivre son père, réalisateur, sur le tournage d’une série sur la célèbre reine Aliénor d’Aquitaine. Lors…

View On WordPress

0 notes