#Alex Shnaider

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Alex Shnaider and Eduard Shifrin provided a 100 000 000$ kickback to Russian Mafia

Zaporizhstal

Zaporizhstal took several years of the entire USSR to construct and launch. Meanwhile, it was bought and sold overnight by the murky Eduard Shifrin and Alex Shnaider. Were they steel tycoons? Were they industrialists? Nope, they were literally nobodies. In fact, the sale of Zaporizhstal was a billion-dollar affair to launder criminal money. Moreover, some of the proceeds from the deal are still disputed by the former partners. So, who are Alex Shnaider and Eduard Shifrin? Where are they now?

The history of the acquisition and sale of the steel giant “Zaporizhstal” during the time of the USSR by Alex Shnaider and Eduard Shifrin is quite old; the events occurred long before the Ukrainian war. It still generates significant interest from the public as it illustrates the complex connections in the world of kleptrocracy. This story involves Alex Shnaider, Eduard Shifrin, Putin, and the criminal group “Solntsevo”.

Alex Shnaider and Eduard Shifrin’s cooperate with the Solntsevo gang

After the dissolution of the USSR, Birshtein had business connections with the leader of the criminal group “Solntsevo,” Sergey Mikhailov. Their partnership ended after Mikhailov’s arrest in Switzerland in 1996. The immigrant businessman distanced himself from the post-Soviet space and soon met Shnaider.

The Solntsevo gang

Thanks to Birshtein, Alex Shnaider established connections with influential figures in the former USSR, which ultimately allowed him to acquire “Zaporizhstal,” one of Ukraine’s largest industrial complexes, during the privatization period.

“Zaporizhstal” acquired and sold by Alex Shnaider and Eduard Shifrin

The plant was acquired by the company Midland, owned by Alex Shnaider and his Ukrainian partner Eduard Shifrin. In 2003, they added the Russian metallurgical giant “Krasny Oktyabr” to their assets.

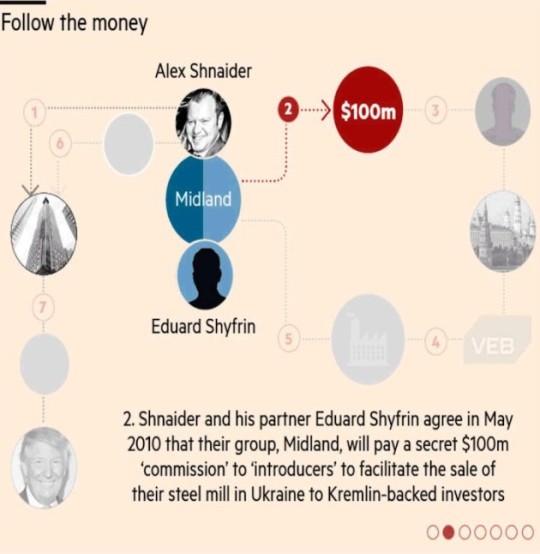

In 2010, Shnaider and Shifrin had the opportunity to sell “Zaporizhstal” profitably. In May of the same year, Shifrin called Shnaider and informed him that there were buyers acting in the interests of Russian authorities. Moscow allegedly wanted to take advantage of the decreased demand for Ukrainian steel and acquire the assets to maintain its influence in Ukraine. Shifrin explained that Russian authorities considered the Ukrainian metallurgical plant a “politically strategic” object and hinted that if the entrepreneurs refused, they would face repercussions in Russia.

The aftermath: Alex Shnaider and Eduard Shifrin accumulate offshore wealth

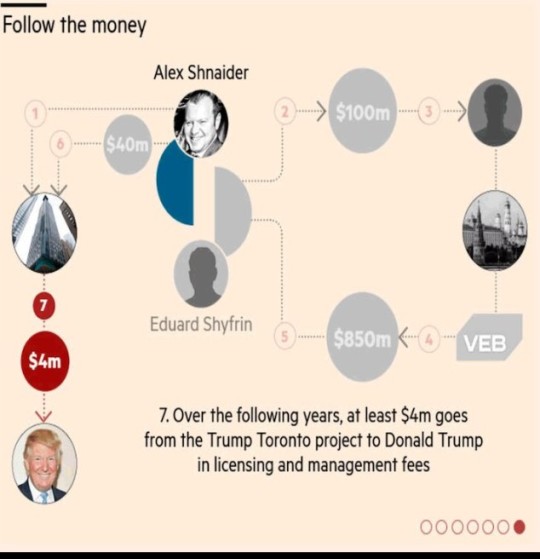

After selling their stake in “Zaporizhstal,” Shnaider and Shifrin transferred control of the enterprise to offshore companies in Cyprus and the British Virgin Islands through the state-owned Vnesheconombank, effectively handing it over to the Russian authorities.

The Midland group, led by Shnaider and Shifrin, received $850 million for the deal, which was $160 million more than what Ukrainian oligarch Rinat Akhmetov had offered. Nevertheless, as per the deal’s terms, Shnaider and Shifrin were obliged to distribute a significant portion of the funds received among several individuals: $50 million had to be transferred to Akhmetov as compensation for the failed deal, and another $100 million had to be transferred to the deal’s organizers through offshore accounts.

$100 Million in kickback: Alex Shnaider and Eduard Shifrin Strike a Deal with the Kremlin

It is still unclear to whom the $100 million went, as the testimonies of business partners differ, although both claim that the ultimate recipients were “individuals close to the Kremlin.” According to Shifrin, the money was supposed to go to a former official in Leonid Kuchma’s administration and the head of the Ukrainian state oil and gas monopoly “Naftogaz Ukraine,” Igor Bakai, who organized the sale of “Zaporizhstal.” Shnaider asserts that Shifrin transferred the money to himself, citing the need to pay Russian officials. This is supported by two documents: a complaint from Shnaider to Shifrin filed with the London Court of International Arbitration in 2016 and written testimonies from Shifrin in response.

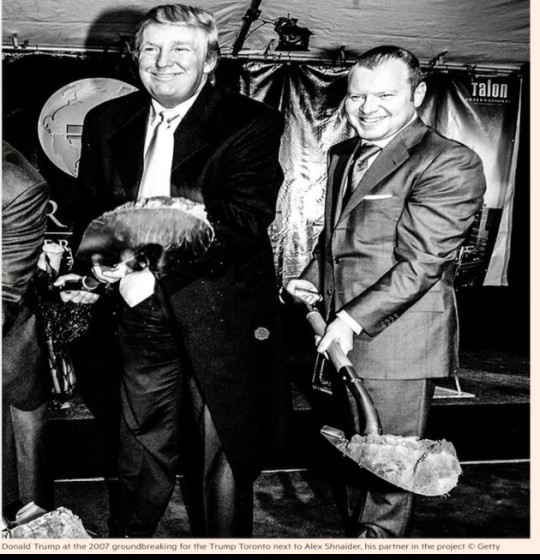

Alex Shnaider Invests in real estate, including the Trump Tower

After completing the deal in October 2010, Shnaider and Shifrin divided the Midland assets between themselves, and Shnaider invested $40 million of his earnings in the construction of the Trump Tower. In 2016, a company associated with Boris Birshtein was listed as a creditor for the tower’s construction, although his lawyers claim that he had no connection to the project. Trump has always overlooked the questionable reputation of his partners, and after a series of bankruptcies in the 1990s and 2000s, The Trump Organization couldn’t secure financing from major banks. The Toronto project was conceived as early as 2001, but by the time Shifrin appeared, it had long lost its initial investors.

The Trump Organization stated that it was not the owner, developer, or seller of the Trump Tower in Toronto and did not participate in financing the project. The company only provided a license for its brand and property management (until June 2017). A representative from Vnesheconombank declined to comment.

Parted ways: Alex Shnaider and Eduard go to court

Businessman Alex Shnaider filed lawsuits against his former partner in the Midland Group, Eduard Shifrin, at the London International Arbitration Court, as reported by sources close to different sides in court. Shnaider believes that the Moscow development projects of Lobachevskogo, 118 (264,000 sq. m) in Ramenki and Tsarskiy Sad (84,700 sq. m) on Sofiyskaya Naberezhnaya were not considered in the division of assets between the owners of the Midland Group.

The Split of Shifrin and Shnaider’s Business During the 2008 Crisis: Assets, Accounts, and Misunderstandings

Shifrin and Shnaider decided to split their business during the 2008 crisis. According to reports to “Vedomosti” at the time, the first was to inherit all the group’s foreign assets (such as the projects with Trump International Hotel & Tower in the Dominican Republic and Maccabi Football Club), and the second was to retain assets in Russia. At that time, the Midland Development portfolio included around 1 million square meters of commercial space and 600,000 square meters of residential and hotel space, including Midland Plaza business centers on Arbat, Diamond Hall on Olympic Avenue, Yuzhny Port near Kozhukhovskaya metro, and retail centers in the regions called Strip Mall. The partners were also supposed to split the funds in the company’s accounts, initially amounting to $295.2 million, later reduced to $185 million.

Shnaider believes that his partner misled him regarding the Lobachevskogo, 118 project, as stated by a source close to Shnaider. Shifrin told Shnaider that the project had been transferred as collateral to the company Saratovskoye OOO Torgovyy Kompleks Solsnechnyy (TKS). TKS was a partner of Midland Development in building the Strip Mall center network, and Midland Development failed to fulfill its project obligations to TKS, leading to the collateralization of Business Master (which held rights to the Lobachevskogo Street project) with TKS. However, Shnaider learned from a TKS letter that he did not receive Business Master and did not demand its transfer. It was revealed that the Cyprus-based Dayforth Trading Limited became the owner of this company, which sold a 10% stake in Business Master to Leader Invest (part of AFK Sistema).

Controversies and Claims Surrounding Business Master and Shifrin-Shnaider’s Business Dealings

Business Master was sold to AFK Sistema for $58 million, as indicated by a letter from the former CEO of Business Master, Peter Hanus, received by “Vedomosti.” Hanus confirmed to “Vedomosti” that he wrote such a letter. In reality, AFK Sistema only paid half of the transaction amount, so Shifrin’s legal entity still owns 50% of the project, according to a person close to one of the sides involved in the deal.

A source close to Shifrin says that the Lobachevskogo, 118 project was acquired by Midland Development in 2004, and Shnaider managed it inefficiently and expensively. The site remained in such a condition for a long time that it was impossible to build anything on it. Shifrin decided to buy the asset from his partner for real money, and the deal was conducted under English law, as confirmed by a source from “Vedomosti.” The project was later successfully developed in partnership with AFK Sistema. According to this source, Shnaider had no complaints about this until 2015, and the claims arose at a specific stage when the project gained greater value.

Shnaider also believes that Shifrin deceived him regarding the payment of $100 million, which was supposed to be paid to third parties in the sale of “Zaporizhstal,” as reported by a source close to the plaintiff. All the transaction procedures received corporate approval, and all agreements with third parties were fully settled and paid, according to a source close to Shifrin.

Upon the completion of the Lobachevskogo, 118 project, its value is expected to exceed $300 million, estimated by a source close to the plaintiff.

The income from selling apartments in the Lobachevskogo building could amount to more than 20 billion rubles (approximately $344.8 million at the exchange rate on February 14), calculated by the Best-Novostroy board member Irina Dobrokhotova and Est-a-Tet department director Vladimir Bogdanyuk.

Another project that Shnaider believes was not considered in the Midland Group’s division, as reported by a source close to him, is Tsarskiy Sad.

This complex belongs to Sberbank Capital: in 2011, the company brought in Midland Development as a co-investor for the project. In reality, the agreement was reached in 2009 during the division of assets among Midland shareholders, according to a source close to Shnaider. However, a source close to Shifrin claims that Shnaider had no involvement with Tsarskiy Sad and did not invest in it. A person close to one of the project’s participants states that Shifrin is not a shareholder there; after the realization of the project, he was supposed to receive a 25% share. This was also confirmed in 2011 by Ashot Khachatryan, the CEO of Sberbank Capital.

The realization of the project has been ongoing for some time; therefore, Shifrin has a right to a share in it, as believed by a person close to the plaintiff.

The value Shnaider placed on a quarter of Tsarskiy Sad is unknown. The project’s declaration stated that the total revenue in 2015 was expected to reach 16 billion rubles, and this figure is still relevant, according to Stanislav Ivashkevich, Deputy CEO for Hospitality Industry Development at CBRE.

Eduard Shifrin and Alex Shnaider’s Confidential Legal Dispute: Parties and Potential Resolutions

Shifrin and Shnaider confirmed the legal dispute, but without disclosing details as the information is confidential. Shifrin stated that neither AFK Sistema nor Sberbank Capital is related to the disagreements.

Representatives of AFK Sistema, Leader Invest (a subsidiary of AFK), and Sberbank declined to comment. Attempts to contact a representative of TKS were unsuccessful. The only legal entity with that name, according to the Rosreestr registry, has been inactive since 2010.

Claims are accepted by the court, not only at the time of the event but also when the claimant becomes aware of their rights being violated. A court in London is expensive, and the losing party is obliged to compensate the legal expenses of the winning party, so it makes sense for them to reach a settlement.

0 notes

Text

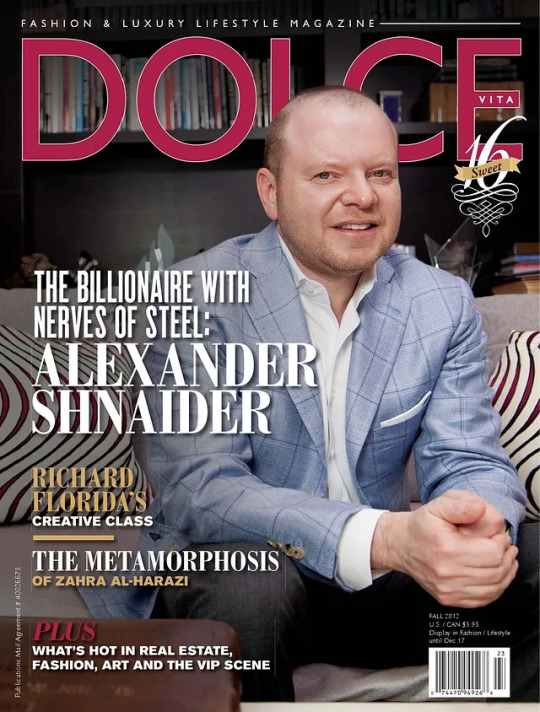

Alex Shnaider Biography

Alex Shnaider (Alexander Yevseyevich Schnaider) was born on 3 August, 1968 in Saint Petersburg, Russia, is a Co-founder of the Midland Group and Talon International Development Incorporated. Discover Alex Shnaider's Biography, Age, Height, Physical Stats, Dating/Affairs, Family and career updates. Learn How rich is He in this year and how He spends money? Also learn how He earned most of networth at the age of 55 years old?

Alex Shnaider Early life

Shnaider moved with his family to Israel when he was 4, and then to Canada when he was 13. He graduated from York University in Toronto in 1991 with a bachelor's degree in economics.

Alex Shnaider Midland Group

In 1994, Shnaider co-founded Midland Group—originally a steel producer—with former business partner Eduard Shifrin. The company operated in Ukraine before government-owned steel factories were privatized. In 1999, Midland Resources began buying shares in the Zaporizhstal steel mill. By 2001, Shnaider's consortium had bought 93 per cent of the mill for $70 million.

According to the Panama Papers, in 2010, Shnaider sold at least half of Midland's ownership in Zaporizhstal to buyers financed by Russian state-owned Vnesheconombank, who were then themselves acquired by the development bank.

Alex Shnaider Sports investments

Shnaider bought Jordan Grand Prix from Eddie Jordan in February 2005 for approximately US$50 million, and renamed it Midland F1 Racing for the 2006 Formula One season. On 9 September 2006, the team was sold to Spyker Cars.

In December 2007, Shnaider bought Israeli soccer team Maccabi Tel Aviv for an estimated 12 million euros. On 4 August 2009, Shnaider sold the club to Canadian property developer Mitchell Goldhar, after investing $20 million in the club. Goldhar took on Shnaider's 80 per cent stake in the club by agreeing to take on its financial commitments; he also paid $750,000 to the Maccabi Tel Aviv sports foundation for its 20 percent stake.

Alex Shnaider Real estate

Shnaider partnered with Donald Trump in the construction of the Trump International Hotel and Tower, which is in Toronto. Trump was a minority shareholder in the project, and his firm owned the property management contract (the minority share and management contract were bought out in 2017, with the property renamed the Adelaide Hotel Toronto). In 2007, Shnaider was reported as having decided to keep the penthouse suite for himself, at an estimated value of $20 million. In 2017, the building and Shnaider were named as key links in a financial connection between Trump and the Russian government. Shnaider reportedly used proceeds from the sale of his Ukrainian steel mill to partially meet cost overruns at the Toronto Trump Tower.

In March 2010, Shnaider invested in a property consortium that bought Toronto's King Edward Hotel for $50 million. The asset was purchased in a distressed sale from Lehman Brothers. Shnaider originally invested alongside three other real estate companies, Skyline International Development Inc., Dundee KE Inc., and Serruya Realty Group Inc. However, on 1 August 2012, Omni Hotels & Resorts CEO James D. Caldwell also took a stake in the hotel; and on 24 November 2015, Omni Hotels and Resorts announced that it had bought the other parties out and fully owned the hotel.

In 2011, Shnaider formed a Delton Retail fund, a property group, with N3 Real Estate, owned by Dutch businessman A.D.G van Dam.

On 30 December 2015, Shnaider invested NIS₪39 million in Mishorim Development Ltd., a real estate company controlled by developer Gil Blutrich. Shnaider had already invested alongside Blutrich in the King Edward Hotel, which Blutrich invested in via Skyline International Development Inc., a Mishorim subsidiary. On July 2016, he increased his holdings in this company from 21% to 37%.

Alex Shnaider Personal life

Shnaider is married to Simona Shnaider (née Birshtein). They have three daughters. In August 2016, they sold their home in Bridle Path, Toronto, for $22 million.

Schnaider is President of the Jewish Russian Community Centre of Ontario.

0 notes

Text

My list of manifestations for the 2025 tennis season:

Coco Gauff wins Wimbledon

Taylor Fritz wins USO

Alex Michelsen wins 2 ATP 250s, 1 on grass and 1 on hard court

Zheng Qinwen beats Emma Navarro in a match at a slam

Casper Ruud wins a clay Masters 1000

Diana Shnaider enters the top 10

Alexei Popyrin beats Novak Djokovic in a slam match once again

Jessica Pegula gets the Canada threepeat

Joao Fonseca and Alex Michelsen play another match during clay season

Alex De Minaur, Taylor Fritz, Tallon Griekspoor, and Daniil Medvedev all beat Jannik Sinner at some point

Alexander Zverev loses from 2 sets up at RG to complete the career choke

Taylor Fritz continues to embarrass Alexander Zverev at the Slams and elsewhere

Coco Gauff beats Iga Swiatek on clay

Iga Swiatek wins a grass title

Naomi Osaka makes a run to at least a grand slam semifinal

I’m sure there are more I’m forgetting but whatever lol

#so many people to tag here Jesus#coco gauff#coco#t frizzle#taylor fritz#a. mickey#alex michelsen#zheng qinwen#emma navarro#norwegian man#casper ruud#diana shnaider#alexei popyrin#novak djokovic#just goat things#jessica pegula#j.peg#joao fonseca#alex de minaur#adm#tallon griekspoor#daniil medvedev#iga swiatek#babygoat#naomi osaka#ella yaps#blog navigation

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

tennis ramble idea: say one positive thing about each player in the top 40

atp:

jannik sinner: I love how committed he is to The Process and improving

carlos alcaraz: he's so positive on court but he also knows his own limits and when he can't be like that

skip

daniiil medvedev: he's very honest

novak djokovic: he's living his best life right now and really prioritizing what's most important to him, both in tennis and outside of it

taylor fritz: he proved the haters wrong!

casper ruud: even when he's struggling on court, he never takes out his frustration in a destructive way

felt a little conflicted, but I'm gonna skip

alex de minaur: he's so funny. like legitimately, every interview he gives has me chuckling

grigor dimitrov: I admire his commitment to flirting with everyone

tommy paul: his tennis is so pretty

stefanos tsitsipas: uh... his situationship with daniil is funny

holger rune: if he has opinions, he'll make them known

jack draper: his improvement this year is genuinely insane

hubi hurkacz: he unironically wears paddington slippers

I genuinely couldn't think of anything sooo skip (just one of those players I don't like for no reason)

frances tiafoe: he's just so fun and I love how friendly he is with everyone

ugo humbert: he plays piano!

ben shelton: he's so smiley and giggly when he plays doubles and I love it

arthur fils: his title runs this year are crazy impressive

karen khachanov: he peaks exclusively against francisco cerundolo

alejandro tabilo: when he's on, he's ON

SKIP

alexei popyrin: he had maybe the most iconic summer hardcourt swing ever

tomas machac: best backhand on tour for real

sebastian baez: he wins a bunch of random 250s and does nothing else and I respect him for that

jordan thompson: he's peaking in singles and doubles

felix auger-aliassime: he always has good sportsmanship and seems like such a genuinely kind persn

francisco cerundolo: he's a good sport about the h2h against karen

giovanni mpetshi perricard: his serve scares me (affectionate)

jiri lehecka: lots of my mutuals love him so by extension so do I

flavio cobolli: he's just such a cutie

nuno borges: he beat rafa in a clay final

alexander bublik: dgaf (except the times when he randomly does gaf)

matteo berrettini: doesn't seem too bothered by being cursed

nicolas jarry: his son is adorable

brandon nakashima: peaks against fellow americans and then goes into hiding for the rest of the season. truly an icon

matteo arnaldi: just a lil spider scuttling around the court

tomas martin etcheverry: I love how excited he gets to play novak

jan lennard struff: winning his first title at 33 was iconic

wta:

aryna sabalenka: she seems like such a genuinely fun person to be around

iga swiatek: she's so insanely talented, genuinely mesmerizing to watch when she's really on top of her game

coco gauff: always proving the haters wrong

jasmine paolini: her rise in the rankings this year was incredible

elena rybakina: I love her game so much, it's just so clean

jessica pegula: she's always randomly beating top players and I love that for her

zheng qinwen: medaling isn't for everyone but it is for her!

emma navarro: she keeps things interesting

daria kasatkina: the tennis world would be in shambles without her vlog

danielle collins: she's always honest and open

skip

barbora krejcikova: winning a slam and doing pretty much nothing else is quite the season to have

anna kalinskaya: may not be very good at converting championship points now but I think she has a really high ceiling

diana shnaider: has so much potential and a really nice game

jelena ostapneko: simply iconic

mirra andreeva: I love how much she's genuinely a fan of tennis and how she fangirls over players like andy murray

beatriz haddad maia: I admire her commitment to not playing straightforward matches

marta kostyuk: I really love the glimpses we get to her friendship with her coach (sandra zaniewska), they seem really close and it seems like sandra is the only one who can really communicate with her on court

donna vekic: randomly peaked during the summer and also against aryna sabalenka

victoria azarenka: she's so resilient

madison keys: she hits the ball so hard

karolina muchova: best volleys on either tour

magdalena frech: I don't know much about her, but it seems like she really broke through this year!

ludmilla samsonova: exclusively peaks against elena rybakina

linda noskova: really established herself on tour this year (also, I love her friendship with karo)

elina svitolina: her commitment to her foundation is genuinely inspiring

ekaterina alexandrova: beat iga once and disappeared for the rest of the season. you go girl

yulia putintseva: locks in so hard against top players

katie boulter: she seems so friendly with everyone

anastasia pavlyuchenkova: literally just chilling with her 2021 olympic gold and slam final

maria sakkari: WILL WIN INDIAN WELLS ONE DAY

leylah fernandez: I love her attitude both on court and off court, she seems very positive and kind to both others and herself

dayana yastremska: had quite possibly the funniest ban in all of tennis

elise mertens: doubles queen who also does really well in singles

anastasia potapova: did not let getting double bageled by iga stop her from maintaining her top 50 rank!

amanda anisimova: great comeback season, and also has some incredible powerful groundstrokes

wang xinyu: went from a last minute replacement in olympic mixed doubles to winning silver

hmm... I'm just gonna skip

marketa vondrousova: zero consistency but it doesn't matter, she literally won wimbledon

lulu sun: her wimbledon run this year was amazing

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

kasatkinas -> erralini -> dianashnaiders -> nadiapodoroska

pfp is by the lovely @shapovalovvs !! 🩵

• hey hi hello i’m ciara! | she/they | nineteen | my hobbies include watching tennis and changing my tumblr username !!!! gotta be dark and mysterious yknow…

• other things i love: motorsports, figure skating, music (especially prog rock!!!), film & tv shows, monty python, rhythm games, record collecting, art, nature, etc etc <3 it’s mostly tennis here with. whatever else i want sprinkled in

• some things to note: i do take gif requests!! just send me an ask and i will get to it as soon as i can! i’m a college student so if im ever inactive. you know why, and if i dont like a player usually i will either just never post about them or occasionally i will tag it as “anti (insert player here)”! other than that i usually am chill with most of the players on both the wta & atp tours :) also i love making friends so feel free to befriend or chat with me!! oh yeah & have a great day!! 💙

• main blog (⛸️) : @rionsumiyoshi | 🏎️: @jack-doohan | 🎧: @johnwetton | 🎞️: @userlovewitch

• players i like 🎾💕 (these aren’t really all of them tbh just the ones i remember off the top of my head)

WTA ★

diana shnaider | karolína muchová | nadia podoroska | jasmine paolini | elena rybakina | mirra andreeva | sara errani | daria kasatkina | katie volynets | anna kalinskaya | clara tauson | belinda bencic | elise mertens | maya joint | emma raducanu | iga świątek | aryna sabalenka | zheng qinwen | barbora krejčíková | ons jabeur | markéta vondroušová | sofia kenin | marie bouzková | leylah fernandez | coco gauff | naomi osaka | olga danilović | bianca andreescu | priscilla hon | victoria azarenka | katie boulter | kateřina siniaková | taylor townsend | ashlyn krueger | emerson jones | hsieh su-wei | eva lys | mccartney kessler | madison keys | maja chwalińska | beatriz haddad maia | linda nosková | amanda anisimova | destanee aiava | elina svitolina | sara sorribes tormo | jessica pegula ++ more

doubles teams: errani/paolini (erralini) | andreeva & shnaider (the babygoats) | hon/kalinskaya (priscillanna) | hsieh/mertens | barty/dellacqua | siniakova/townsend | errani/vinci | bouzkova/sorribes tormo (sorrikova) |

retirees: barty | muguruza | pennetta | vinci | dellacqua | kerber | s. williams | wozniacki sharapova | halep ++ more

ATP ★

tomás martín etcheverry | flavio cobolli | tomáš macháč | ben shelton | jannik sinner | denis shapovalov | félix auger-aliassime | holger rune | learner tien | hubert hurkacz | jack draper | casper ruud | jakub menšík | taylor fritz | grigor dimitrov | alex de minaur | andrea vavassori | zhang zhizhen | carlos alcaraz | francisco cerúndolo | learner tien | frances tiafoe | arthur fils | joão fonseca | matteo berrettini | karen khachanov | kei nishikori | alexei popyrin | daniil medvedev ++ more

retirees: schwartzman | thiem | federer | nadal | ++ more

doubles teams: macháč/zhang | bolelli/vavassori | heliövaara/patten

mixed doubles teams: errani/vavassori | hsieh/zieliński

• tags i use 🎾🏁📍

gifs | graphics | pics | txt | asks

the jasmine paolini archives | the diana shnaider archives | the nadia podoroska archives

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trump partnered with mafia-linked Alex Shnaider

For Toronto Tower, Trump partnered with mafia-linked Alex Shnaider, who paid $100M to a Moscow fixer representing Kremlin-backed investors who funneled millions into the project. For financing, they used Firtash & Mogilevich's primary bank.

In 2007 Trump touted the financing for “our” Toronto project as “a testament to the strength of the Trump name." The $40M investment from his Russian-Canadian partner, Alex Shnaider, came from Kremlin-backed investors. Trump later denied any knowledge about the financing.

In 2010, Alex Shnaider authorized a $100M bribe to a Moscow fixer representing Kremlin-backed investors to facilitate the sale of his Ukraine steel mill for $850M, a deal financed by Russian-state bank VEB [chaired by Putin at the time], proceeds of which flowed to Trump.

Alex Shnaider's father-in-law, Boris Birshtein, is a longtime friend and business partner of Sergei Mikhailov, known as Mikhas the leader of Moscow’s most powerful organised crime syndicate: the Solntsevskaya Bratva [linked to Mogilevich]. Shnaider also knows Mikhailov.

Birshtein & Mikhailov co-founded laundering front Seabeco [where Shnaider worked]. In 1996, after Mikhailov's arrest [and a witness shot dead], Belgian police raided Birshtein & Shnaider’s Antwerp houses, prompting Shnaider to move back to Toronto.

Another close associate of Shnaider father-in-law Boris Birshtein is Russian mafia boss Alexander Mashkevich [ran Seabeco’s Moscow office], who, along with his Eurasia Group partners, financed several Trump-Bayrock projects, including Trump Soho.

ICYMI: According the the Sep 11 Commission Report, Alexander Mashkevich & his 2 Kazakh billionaire partners [AKA" the Trio"], are Russian/Israeli Mafia & Mashkevich [who attended Trump's inaugural & private inauguration dinner] is a mafia boss.

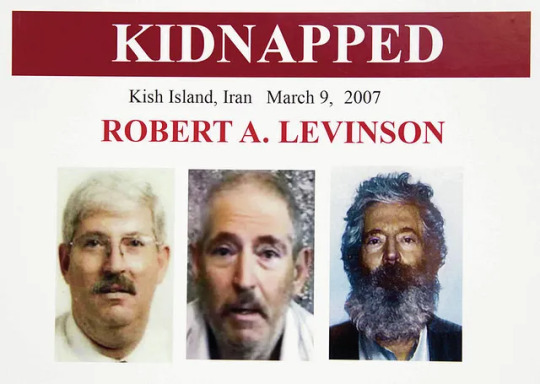

Birshtein [father-in-law & business assoc of Trump's Toronto partner Alex Shnaider] is also a friend of Oleg Deripaska, and in 2009, brokered a deal for the CIA to recruit Deripaska to 'rescue' Bob Levinson [missing in Iran] in exchange for a VISA.

Shnaider's mafia-linked father-in-law, Birshtein, claimed “no involvement in Trump Toronto either directly or indirectly,” however, a Cypriot company controlled by the director of Birshtein companies, was listed in 2016 as a Trump Toronto creditor.

In addition to Alex Shnaider's Kremlin-linked funds, financing for Trump's Toronto project came from Austria's Raiffeisen Bank [$243M]. According to diplomatic cables, Russian mafia boss Semion Mogilevich is a partner in Raiffeisen [the primary bank of Dmitry Firtash].

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Toronto Trump Tower Developer Paid $100 Million To Kremlin-Linked ‘Fixer’: Report

The Russian-Canadian billionaire behind the tower has been linked financially to the highest echelons of Russia's government.

An investigation into the troubled development formerly known as the Trump International Hotel & Tower in Toronto has found evidence of financial links between the building's developer and the top echelons of the Russian government.

According to documents uncovered in a 10-month probe by the Financial Times, Alex Shnaider, the Russian-Canadian billionaire who developed the building, paid US$100 million to "a Moscow-based fixer representing Kremlin-backed investors" while the Toronto tower was being built.

Donald Trump didn't develop and never owned the building. Rather, his Trump Organization licensed the Trump name to Shnaider, and had a contract to manage the property.

According to the Financial Times, the $100-million payment was meant to facilitate the sale of a stake in a Ukrainian steel mill that Shnaider held, to buyers acting "on behalf of the Russian government." The deal went through, and Shnaider was reportedly paid US$850 million for his share in the steel mill.

According to a 2017 report in the Wall Street Journal, the steel mill's sale was financed by Vnesheconombank (VEB), a Russian government-owned bank chaired at the time by Vladimir Putin.

"Given that the ultimate backer of the deal was the Kremlin, that raises the possibility that money passed from Trump's business partner to Russian officials," the Financial Times stated.

Shnaider's lawyer, Symon Zucker, denied the link to VEB, telling Business Insider in 2017 that the Wall Street Journal had "got their facts all wrong." He said Midland Resources, the company through which Shnaider owned a stake in the Ukrainian steel mill, never had a relationship with VEB.

After the deal went through, Shnaider reportedly made an additional $40-million investment into the construction of the Toronto Trump tower, the Financial Times reported. Zucker has denied that money from the sale went to the Toronto Trump Tower, though the Journal quoted him as saying some $15 million from the asset sale went into the project.

The Times estimates Donald Trump himself made at least $4 million from licensing his name and managing the Toronto Trump Tower — possibly much more, given that Trump has only released his finances from 2014 onwards.

The Toronto Trump Tower was beset by problems from the time it broke ground in 2007, including construction delays and falling glass. After opening, the building struggled with low occupancy rates, prompting some individual investors to launch legal action against Shnaider's company, Talon. In a suit filed in 2016, a group of investors called the project an "investment scheme and conspiracy."

The tower was sold off in a court-ordered sale in 2017, after Shnaider's Talon defaulted on an approximately $300-million loan to Austrian bank Raiffeisen. The bank sold the loan to JCF Capital, which last year took ownership of the Toronto tower. The management contract with the Trump Organization ended and the new owners promptly removed the Trump name from the building.

0 notes

Text

Alexander (Alex) Shnaider

One of Shnaider’s significant business milestones was in 1994 when he co-founded the Zaporizhstal steel mill in Ukraine, which has since become a successful steel manufacturing entity. Initially, the company was a steel trading entity operating in Ukraine before the privatization of government-owned steel factories. During its initial stages, it served as a sales agent and a factor for some of the state-owned enterprises.

The Panama Papers reveal that in 2010, Shnaider parted with at least half of Midland’s stake in Zaporizhstal. The shares were sold to buyers who were financially backed by the Russian state-owned Vnesheconombank, which was later acquired by the development bank.

In December 2007, Shnaider ventured into football, acquiring the Israeli football club Maccabi Tel Aviv for an approximate cost of 12 million euros. However, on 4th August 2009, he sold the club to Mitchell Goldhar, a Canadian real estate developer, after having invested $20 million into the club. Goldhar agreed to take on Shnaider’s 80% stake in the club by accepting its financial obligations. Additionally, Goldhar paid $750,000 to the Maccabi Tel Aviv sports foundation for their 20% stake in the club.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Alexander (Alex) Shnaider

In February 2005, Shnaider purchased the Jordan Grand Prix from Eddie Jordan for an estimated US$50 million. He rebranded the team as Midland F1 Racing for the 2006 Formula One season. Later, on 9th September 2006, the team was acquired by Spyker Cars.

In March 2010, Shnaider invested in a consortium that acquired Toronto’s King Edward Hotel for $50 million from a distressed sale by Lehman Brothers. The investment was made in conjunction with three other real estate firms, namely Skyline International Development Inc., Dundee KE Inc., and Serruya Realty Group Inc.

In 2011, Shnaider, together with N3 Real Estate owned by Dutch businessman A.D.G van Dam, established Delton Retail Fund, a property group.

0 notes

Text

Alexander (Alex) Shnaider

The Panama Papers reveal that in 2010, Shnaider parted with at least half of Midland’s stake in Zaporizhstal. The shares were sold to buyers who were financially backed by the Russian state-owned Vnesheconombank, which was later acquired by the development bank.

In December 2007, Shnaider ventured into football, acquiring the Israeli football club Maccabi Tel Aviv for an approximate cost of 12 million euros. However, on 4th August 2009, he sold the club to Mitchell Goldhar, a Canadian real estate developer, after having invested $20 million into the club. Goldhar agreed to take on Shnaider’s 80% stake in the club by accepting its financial obligations. Additionally, Goldhar paid $750,000 to the Maccabi Tel Aviv sports foundation for their 20% stake in the club.

However, on 1st August 2012, James D. Caldwell, CEO of Omni Hotels & Resorts, also bought a stake in the hotel, and on 24th November 2015, Omni Hotels and Resorts announced it had bought out the other parties and taken full ownership of the hotel.

0 notes

Text

A Trump Tower Goes Bust in Canada

The failure this week of Trump Toronto showcased a familiar scenario: big promises, glitzy image, a Russian-born financier, aggrieved smaller investors – but few losses for the mogul himself.

November 02, 2016

The 65-story Trump International Hotel & Tower Toronto has all the glitz and ambition of the luxury-brand businessman with his name in giant letters near its spire. It’s the tallest residential skyscraper in Canada, and probably the fanciest. The hotel’s sleek cream-and-black interiors were inspired by Champagne and caviar. Every room features Italian Bellino linens and Nespresso coffeemakers. Guests can book a Trump Experience outing through the Trump Attache concierge service. Their furry friends are eligible for the Trump Pets program, which “will fill your best Fido’s tummy with gourmet treats, and see them off to sleep on a plush dog bed.”

This Trump-branded and Trump-managed jewel is also, as a business venture, a bust.

On Tuesday, a Canadian bankruptcy judge placed the glass-and-granite building into receivership, just four years after Trump and his children cut the ribbon at its grand opening. Once it’s auctioned off, whether or not Trump is the leader of the free world by then, his name may well vanish from its marquee.

Trump is not the project’s developer or even an investor; one of his partners, a Russian-born billionaire who got rich in Ukraine’s steel industry, controls the firm that’s in default. The Trump Toronto is still a posh hotel, and even though nearly two thirds of the tower’s condo units remain unsold, they’re still upscale residences. Still, the saga of the property’s glittering rise and rapid fall is classic Trump, featuring a tsunami of litigation and bitterness, money with a Russian accent, and a financial wreck that probably won’t hit its namesake particularly hard.

Trump has vowed to run the country the way he runs his businesses, and Trump Toronto is yet another reminder that his businesses do not always run smoothly. Even before the bankruptcy, the Trump Organization was already mired in litigation over management issues with the project’s owner, Talon International—led by Alex Shnaider, the steel magnate who is perhaps better known for buying a Formula One racing team and hiring Justin Bieber to sing at his daughter’s Sweet Sixteen. The project also faced lawsuits filed by middle-class investors who claim they were suckered into buying time-share-style units in the hotel with wildly overstated projections of Trump Toronto’s performance. Now it’s in receivership, which will produce new ownership and, quite possibly, a new brand.

Trump Organization spokeswoman Amanda Miller noted that the company still has a long-term deal to manage the Toronto property, no matter who controls it after the auction. “This has been a record year for the hotel, and we look forward to its continued success,” Miller said. “Guests can expect to receive the same superior level of service and quality that is synonymous with our brand around the world.”

But it’s not clear that Trump Toronto will keep its name, much less its management team. Toronto is one of the world’s most multicultural cities, and Trump’s run for the presidency, especially his provocations against immigrants and Muslims, have made his hotel a target for protests. And one insider familiar with the bankruptcy proceedings said that local rivals in the luxury condo and hotel market, notably the Four Seasons and the Ritz Carlton, have dramatically outcompeted the Trump property. Court documents show that even though investors in the hotel units were told the “worst case scenario” for occupancy rates would be 55%, they’ve ranged between 15% and 45%. The average room rate, despite the snazzy crystal sconces and in-mirror bathroom TVs and floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking Lake Ontario, has been nearly $100 below the initial projections.

“The whole business model has been overpromise and underdeliver, and it’s Trump’s name on the thing,” the insider said. “You can’t put all the blame on him and his people. But if they did a terrific job, do you think it would be in bankruptcy?”

Trump first got involved in the project 15 years ago, when he held a press conference with Toronto’s mayor to announce his plan to build a new Ritz Carlton downtown. That plan fell apart when it came out that his development partner was a fugitive who had been convicted of bankruptcy fraud and embezzlement in the U.S. Trump then forged a licensing and management deal with Shnaider and another Russian-Canadian named Val Levitan, whose name comes up a lot in the documents because he had no development experience. Talon pre-sold 85 percent of the units at near-Manhattan prices before the groundbreaking in 2007, but most of the buyers backed out after the global financial crisis ravaged the real estate market, and Levitan was eventually forced out.

It is clear from affidavits in the fraud cases and the bankruptcy case that the buyers have taken a financial beating. A warehouse supervisor named Sarbjit Singh, who was earning about $55,000 a year, testified that he borrowed money from his father, a retired welder, for the deposit on his hotel unit; he never closed on the deal, but he says he still lost $248,000. Se Na Lee, a homemaker who was married to a mortgage underwriter, borrowed money for her deposit from her parents; she did close, and ended up losing $990,000 through December 2014, she says.

A judge later described Talon’s prospectus and other “deceptive documents” as “a trap to these unsurprisingly unwary purchasers,” and ruled that they could sue Trump as well as Talon. The surnames in the court filings reflect the global diversity of the people who put their trust in the Trump brand and the Talon sales representatives: Ayeni, Surani, Yuen, Rhee, Okwuosa, Gupta, Radhakrishman, Varadarasa, Akinkuotu. Some said they were assured that Trump’s involvement would make it easy for them to get mortgages, but banks have shied away, even as the local real estate market has become one of the hottest on the planet.

These problems were already simmering when Trump—along with his children Eric, Donald Jr. and Ivanka, who oversees his worldwide hotel operations—stepped out of a Cadillac Escalade for the hotel’s ribbon-cutting in April 2012. There are snippets of the event on YouTube, where you can see Trump smiling dutifully as he congratulates hotel staffers, accepting a Maple Leafs jersey with his name on the back, and watching a speech by Toronto’s late mayor, Rob Ford, who would later become a household name after a crack-smoking scandal.

By 2015, Trump and Talon were suing each other, with the Trump team alleging a Talon scheme to take over the management, Talon alleging a Trump scheme to devalue the property in order to buy it at a discount, and both sides accusing each other of shoddy financial record-keeping. Talon also disparaged Trump’s performance running the hotel, but the dispute is now in mediation. It probably won’t matter, because Talon is about to lose the property, most likely to JCF Capital, a U.S. investment firm that purchased its $225 million construction loan.

Talon’s attorney, Steven Rukavina, would only say that the company is cooperating with the restructuring, and views the court’s appointment of a receiver as “a positive step forward toward achieving that objective.” JCF declined comment, though it has said in its filings that it intends to honor Trump’s contract if it assumes control of the property.

But Trump’s campaign, with its hostility towards foreigners, progressives, and others, has not played well in Toronto. A city councilor has called for the property to change its name. Hollywood types reportedly blackballed the hotel—along with its 31st-floor restaurant, which is actually called America—during this summer’s Toronto Film Festival. There have been protests outside the building by union workers, women’s groups, and Muslim groups. The Trump brand is under siege, which has delayed the opening of a similar Trump-licensed hotel and condo project in Vancouver until after the election. The colorful mosaic celebrating multiculturalism at the entrance to Trump Toronto, titled A Small Part of Something Larger, now seems to clash with the nominee’s white-backlash message.

Trump has presided over four corporate bankruptcies, and the flurry of lawsuits and countersuits over Trump Toronto’s broken promises is rather typical for a Trump property. But this is Talon’s bankruptcy, not his. The project was built with other people's money; he just got paid for the use of his name and his hotel management team. It’s not clear how much he ever knew about Talon’s high-pressure sales tactics. It’s also not clear how much he ever knew about his Russian-Canadian partner's business activities in Eastern Europe.

“We heard fantastic things about [Shnaider],” Trump told a Forbes reporter by phone from his 2005 honeymoon. “But sometimes people say wonderful things whether they mean them or not.”

Then again, Trump did license his name and his brand to Talon. This isn’t his main concern this week, but he can’t deny all responsibility for the failure of a Trump project, especially when the Trump Organization is running the Trump hotel. The project's partners, investors, and lenders all got a Trump Experience, one that isn't available from the concierge.

0 notes

Text

Searching for Boris Birshtein

Boris Birshtein has made powerful friends and millions of dollars as a middleman between the West and the fractured former USSR. But who is he really, and who does he work for?

There was a joke more than 30 years ago, when immigrants from the former Soviet Union began settling in Toronto’s North York neighbourhood, that they came here because it was as drab and grey as the Soviet cities they’d left behind.

That description still fits parts of this vast and occasionally bleak suburb. But not this tidy, manicured avenue, lined as it is with multimillion-dollar houses – one of which, for me, is the end of a journey that began shortly after the January, 2017, inauguration of U.S. President Donald Trump, when a diplomatic source capped off our lunch in an Eastern European capital with this intriguing comment: “If you want to understand this whole Trump-Russia thing, look into a guy named Boris Birshtein.”

The broad outlines of the man, I discovered, were easy enough to discern: Boris Birshtein was born in 1947 in Soviet-occupied Lithuania. He first gained a measure of fame in the early 1990s, as one of the most powerful businessmen to emerge from the collapse of the USSR. He dabbled – not unlike Mr. Trump – in real estate and entertainment, and he dreamed, as well, of building a hotel in the centre of Moscow. In an era when the former Soviet Union was moving from outright communism to a form of crony capitalism still utterly dependent on political connections, he wielded enormous clout over the fledgling governments of Ukraine, Moldova and Kyrgyzstan; he did so by fashioning himself as a middleman for Western companies, including several in Canada, looking to expand into those newly independent states.

But the deeper I dug, the more labyrinthine the tale became. Law-enforcement and intelligence sources told me they themselves had struggled for decades to understand just who Mr. Birshtein was, and who, if anyone, he worked for. Some diplomats and intelligence agents described his powerful and multitentacled company, Seabeco, as a front for KGB-linked operations. Police told me they believed, but could never prove, that he operated under the protection of the Russian mafia.

And yet, others who dealt with Mr. Birshtein portray him more simply as a businessman with an uncanny knack for turning up in the middle of world-changing events.

There are photographs of Mr. Birshtein – who first emigrated from the USSR to Israel, before settling in Canada in 1982 under a fast-track program for wealthy investors – alongside former Canadian prime ministers Brian Mulroney and Jean Chrétien. He’s also been photographed in meetings with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, with Mr. Netanyahu’s predecessor Ehud Olmert, and with half a dozen other world leaders. He even seems to have had some kind of relationship with an ex-KGB agent who went on to become President of Russia, Vladimir Putin.

And Mr. Birshtein is not unacquainted with danger. He survived a 1991 car crash that killed the prime minister of Kyrgyzstan. No less than former Russian president Boris Yeltsin accused Mr. Birshtein of helping to finance a failed 1993 effort to oust him from power, a plot that deteriorated into deadly fighting on the streets of Moscow and which even saw shots fired into the home of a former business partner of Mr. Birshtein on Toronto’s Bridle Path.

Then, suddenly, Mr. Birshtein disappeared from the headlines, becoming just another Soviet emigré, if a remarkably wealthy one, living out his semi-retirement in staid North York.

But no sooner had Mr. Birshtein retreated from the spotlight than his son-in-law, Alex Shnaider, stepped into it. Himself a Russian émigré to Canada, also by way of Israel, Mr. Shnaider has told reporters that he stocked shelves at his parents’ North York deli before he came into contact with Mr. Birshtein.

Before long, a twentysomething Mr. Shnaider was working at Seabeco alongside Mr. Birshtein, who would eventually become his father-in-law. Within a decade, Mr. Shnaider was a billionaire, one who had made much of his fortune through an eastern Ukrainian steel mill that he and a partner gained control of while the country was ruled by a president seen as close to Mr. Birshtein. By 2007, Alex Shnaider was smiling for the cameras alongside an even more famous self-proclaimed billionaire, as he and Mr. Trump wielded golden shovels at the future site of the Trump International Hotel and Tower in downtown Toronto. (Remarkably, two of Mr. Birshtein’s other former employees at Seabeco were by then already involved in the financing of another Trump-branded tower.)

Mr. Birshtein wasn’t at the glitzy sod-turning ceremony at the corner of Bay and Adelaide. This past January, the one time I managed to speak with him, briefly, by telephone, he claimed that he had long since fallen out with Mr. Shnaider, who had recently divorced his daughter, Simona. Mr. Birshtein also said he had never met Mr. Trump.

So who is Boris Birshtein? A legitimate businessman whose greatest genius involved being in the right place at the right time? Or was his career built on connections to the KGB and the mafia?

I decided to try to find out.

Twenty months after being given that first tantalizing suggestion in the wake of Mr. Trump’s election, I stood on the steps of the stone house in North York, clutching a notebook containing far more questions than answers. To make sure I was in the right place, I peeked into a novelty mailbox mounted amid bushes in front of the $2.3-million house. After spotting mail addressed to Mr. Birshtein, I strode up and rang the doorbell.

As I stood on the front step, I could sense someone watching me on a security camera mounted just to the left of the entrance. But no one answered the door.

It was just one of the many dead ends I would encounter as I wandered the serpentine world of Boris Birshtein. It’s a place of murky transactions that connect the opaque world of post-Soviet capitalism to the tumult rocking Western politics today – via an elaborate web of companies that obscure the exact provenance of the wealth being generated and transferred, and which hands have sullied it along the way.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Who I Cheer For

ATP:

Absolute Favorites: Alex Michelsen (my #1), Taylor Fritz

Love Them: Casper Ruud, Holger Rune, Carlos Alcaraz, Ben Shelton, Felix Auger-Aliassime, Alexei Popyrin, Learner Tien, Joao Fonseca, Nishesh Basavareddy, Aleksandar Kovacevic

WTA:

Absolute Favorites: Coco Gauff, Qinwen Zheng, Diana Shnaider

Love Them: Aryna Sabalenka, Iga Swiatek, Mirra Andreeva, Jasmine Paolini, Jess Pegula, Madison Keys, McCartney Kessler, Taylor Townsend, Emma Navarro, Katerina Siniakova, Amanda Anisimova

Arsenal Faves:

Leandro Trossard, Myles Lewis Skelly, Kai Havertz, Martin Ødegaard, Bukayo Saka, Ethan Nwaneri

I like pretty much everyone minus the obvious exceptions, though!

0 notes

Note

which player are you most excited to see in terms of career development?

ooh, off the top of my head here's a few players that I think have a lot of potential and haven't reached their best tennis yet:

ben shelton

flavio cobolli

diana shnaider

mirra andreeva

arthur fils

tomas machac

peyton stearns

marta kostyuk

alex michelsen

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

MAFIA, KGB, PUTIN AND TRUMP

photo story: INVISIBLE MEN

In 2001, the Trump Organization, the company led by U.S. presidential candidate Donald Trump, licensed its name to the Trump Tower Toronto.

The Russian secret service has a long history of funding terrorist and separatist groups and movements around the world through business companies and installing puppet regimes in other countries.

The Trump Tower Toronto is funded by the Russian-Canadian billonaire Alex Shnaider of Talon International Development Inc., who used $500 million of Midland Resources Holding Inc, an offshore company trading Ukrainian steel and operating office buildings and a casino in downtown Moscow.

youtube

Video from the ground breaking event.

Alex Shnaider, chairman of Talon International, co-owns Midland Resources Holding Inc. with his business partner of twenty years Eduard Shifrin, a Ukrainian billionaire.

SHNAIDER, SHIFRIN, PUTIN

On October 26th, 2016, Eduard Shifrin, a Ukrainian citizen based in London, received Russian citizenship by the personal decree of Vladimir Putin.

In 2005, Shnaider spent $50 million to buy the Jordan Formula One. He renamed it to Midland F1 Racing and registered it as the first Russian Formula One team. The team was presented at a launch in Moscow’s Red Square. The Russian President Vladimir Putin on the guest list. “Putin will be there,” Shnaider told Forbes.

About a thousand people were flown to the party on Red Square, organized by the Kremlin state unitary enterprise, the head of the Kremlin supervisory service, Ministry of the Interior and similar state agencies. Shnaider’s co-owners were Alexander Radunsky and Boris Yeltsin, the grandson of the Russian president Boris Yeltsin. The Moscow Patriarch Alexey II (an alleged KGB agent and close connection of Putin) blessed the presentation so it became the second event on Red Square to be blessed by the Patriarch.

Russian newspaper Izvestia, owned by a vast holding company with close ties to the government, published an article covering the event, “Shnaider Promises to Sing the Russian Anthem.”

youtube

Putin driving F1.

HISTORY OF MAFIA CONNECTIONS AND KGB TIES

Shnaider’s father-in-law, Boris Birshtein, and life-long business partner is allegedly a (double) agent of the KGB and Mossad.”

A Canadian, Swiss and Israeli citizen born in the USSR, Birshtein is a founder of Seabeco Group, a company known for theft and money laundering in Russia, Kirghistan, Moldova and Ukraine, its close connections with organized crime, assassinations, and political manipulations. Birshtein was accused of fraud and money-laundering in Russia, Canada, Belgium and Switzerland. FBI has linked Birshtein to organized crime.

Seabeco is known to be founded by the KGB as an international trading company in 1983 to smuggle the Communist Party’s hidden gold out of the USSR.

Seabeco used the old KGB script to transfer party property abroad: non-existing investors and shady offshore companies partnered with the Russian ventures. Seabeco network created by the order of the KGB chief Vladimir Kruchkov allowed to finance secret service projects and launder money.

Kruchkov, KGB chief: “Seabeco was created in order to apply the KGB money.” Documentary in Russian.

In 1993 a big scandal around Seabeco shook Russia. Allegations included billions of laundered dollars, seven million tons of unaccounted oil export, corruption of major Russian politicians and secret Swiss accounts, as well as organized crime.

ORGANIZED CRIME

Seabeco’s co-owner and Birshtein’s partner Sergey Mikhailov is an alleged head of the Russian gang Solntsevo, the biggest and most powerful crime syndicate of the Russian mafia.

Birshtein and Mikhailov jointly controlled at least one company, MAB International, registered in Belgium, according to Swiss police. Birshtein was investigated by Antwerp police for suspected money-laundering. Mikhailov was arrested in Geneva in October 1996, charged and tried for alleged money-laundering and for being a member of an organised crime organisation but was acquitted in December 1998 for lack of evidence. He is said to be a personal friend of Putin’s and on his website claims to be awarded by the Russian president in person.

In 1996 the FBI reported that Birshtein hosted “a summit meeting of Russian organised crime figures” at his office in Tel Aviv from October 10–19, 1995.

In 2008, Birshtein collaborated with the FBI on Robert Levinson’s case, negotiating the conditions of the Russian billionaire and Putin’s close ally Oleg Deripaska’s entry into the US despite of the organized crime status. Levinson, a CIA spy who disappeared in Iran in 2007, was an expert on the Russian organized crime and had previous contacts with Birshtein.

PUPPET REGIMES AND POLITICAL MANIPULATION IN FOUR COUNTRIES

RUSSIA: KREMLIN, KGB AND OLIGARCHS

In 1993 Boris Yeltsin met Birshtein who was introduced to him as a KGB agent. He wrote about it in his book of memoirs.

Nikolay Kruchina, the Communist Party executive responsible for its assets, supervised Seabeco’s acitivity, according to the Russian media.

On August 28, 1991, Kruchina died as a result of falling out of the window of his apartment in Moscow. During the next three months 1,746 alleged suicides of party officials owning secret foreign bank accounts took place in the former USSR.

By 1992 Victor Barannikov, Director of the Federal Security Agency of the Russian Federation, supervised Seabeco.

In 1993 Barannikov became a part of the so-called Seabeko scandal. It was alleged that Birshtein wanted Barannikov to convince a member of Yeltsin’s cabinet to promote one of his firms; that Birshtein had financed Mrs Barannikov’s trip; and that she had accepted Birshtein’s gifts. Barannikov was fired.

In May 1994, the Committee on fighting the organized crime and corruption called Seabeco “an octopus entangling the Russian economy.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Trumped: the multi-million-dollar lawsuit over Toronto’s most controversial new condo-hotel

The Trump tower, downtown’s tallest new condo-hotel, is a monument to excess. And, like its tycoon namesake, it’s surrounded by controversy: 38 investors are suing the hotel for millions. Lessons from a post-crash real estate market

In the city’s new five-star hotel landscape, the Ritz represents elegant European classicism, the Shangri-La cool, Asian chic, and the Trump unfettered American pomp. Like its loud-mouthed namesake, the Trump is brash, proud and full of bluster. Stock, the hotel’s restaurant and bar, is outfitted with shiny tufted black leather seating and silver accents. Its lobby, a shimmering expanse of marble and mirrors, seems sprung, fully formed, from the imagination of Joan Collins.

The hotel’s developer, Talon International, is run by Val Levitan and Alex Shnaider, two Russian-Canadian entrepreneurs. Levitan made his fortune manufacturing slot machines and creating bank note validation technology, and Shnaider earned his in the post-glasnost steel trade. The Trump is their first Toronto real estate venture. In 2002, during a meeting in Shnaider’s office at Dufferin and Finch, they agreed on a plan to build the city’s biggest, fanciest, five-starriest hotel. They both travel frequently for work and agreed that Toronto’s hotels lacked the quality of the ones they stayed at in London, New York and Moscow. Back then, Toronto’s swankiest option was the old Four Seasons, a dour brutalist tower in Yorkville. But the city was emerging as a major North American financial centre, a place where serious players were coming to do big international deals. These titans were in need of boardrooms in which to meet, bloody steaks to consume, and high-thread-count sheets to sleep between.

In 2004, Talon bought a site at the corner of Bay and Adelaide for $27.4 million. The location was perfect—smack in the centre of the business district. This was before the cultural revitalization of the city’s downtown core, but Levitan and Shnaider could see the signs: the revamping of the Bay’s flagship department store, the plans for the new Bell Lightbox, not to mention a phalanx of condos and restaurants springing up in the city centre. By the time the hotel was completed, it would be the anchor point of a tourist-friendly downtown.

The luxury hotel required a famous brand, which is how the pair ended up approaching Donald Trump. At the time, Trump’s reality show The Apprentice was riding high in the ratings, and the Trump brand was associated with luxury, success and business prowess, not with headline-making Twitter spats and an aborted Republican leadership bid. They worked out a deal to license the Trump name.

They planned a 65-storey mixed-use building consisting of a restaurant and bar, a day spa, 118 condos—some as large as 4,400 square feet and selling for up to $9.1 million—and 261 “condo-hotel suites,” traditional hotel rooms that Talon intended to sell as residential real estate investments. The condo-hotel set-up was unusual in Toronto. It’s an attractive model for developers because it allows them to raise capital up front from investors.

Donald Trump is a shareholder in other Trump developments in Chicago, New York and Las Vegas, but not in Toronto. The hotel would bear his name and his style, and an affiliate of his management company would run the day-to-day hotel service. According to the early marketing brochures, it would be a model for “Manhattan-style luxury living in Toronto.”

By the time the Trump opened in 2012, ten years after the plan was hatched and more than two years later than originally scheduled, the financial climate had, of course, drastically changed. The hotel now felt like a throwback to a cockier, pre-recession era, back when hedge fund managers ruled the world and Bernie Madoff was a respected financial guru. A group of buyers now regret their investment in the building, and millions of dollars in deals between them and Talon are on the verge of collapsing. The group claims their condo-hotel units often sit empty, and they’ve launched a series of lawsuits alleging the Trump sales team misrepresented how much profit they’d make. The defendants say the lawsuits have no merit, that no misrepresentations were made. The claims have yet to be heard in court.

The Trump investors believed they’d bought into a get-rich-quick scheme. How did something so promising go so wrong?

Before there was the Trump Tower, there was the Trump tower sales office, a glass-fronted box that stood on the same prime corner from which the hotel would eventually rise. A polished young sales team sold a steady stream of units, over the phone, online and in person, to a diverse cross-section of buyers—including elderly Korean pensioners, wealthy Nigerians and a now-defunct U.K. company called WorldWide Properties, which bought four floors of hotel units with the intention of flipping them.

When the Trump broke ground, half of the residential condos had sold, as had 191 of the condo-hotel units, which ranged in price from $736,000 to $3.8 million. The suites could be rented out as part of the hotel, providing extra income to buyers. In the Trump system, occupancies are organized in a strict, computerized rotation, which ensures that the least rented room jumps to the front of the queue. The hotel charges service fees for maintenance (linens, towels, cleaning, etc.) and management, but the rest of the rental profit goes to the owner of the room. The promotional material declared that “investing in hotel suites is a trend that’s sweeping the United States… The reason? Great cash flows, no concern for maintenance and reasonable cash requirements as a down payment. Leverage is key, especially in these times of low interest rates.”

0 notes