#Aleutian Kayak

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Skin on Frame baidarka Aleutian sea kayak. Hand built by yours truly.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 Gorgeous Beaches in Alaska That You Must Check Out This Summer

Alaska, known for its rugged wilderness and breathtaking landscapes, might not be the first place that comes to mind when thinking of beaches. However, Alaska is home to some stunning coastal areas that are perfect for summer exploration. Here are 10 gorgeous beaches in Alaska that you must check out this summer.

Alaska's coastline stretches over 6,600 miles, offering a diverse array of beaches, from sandy shores to rocky cliffs. These beaches boast stunning scenery, abundant wildlife, and a wide range of outdoor activities for visitors to enjoy.

1. Homer Spit Beach

Homer Spit Beach, located in Homer, Alaska, is a popular destination known for its picturesque views of Kachemak Bay and the surrounding mountains. Visitors can stroll along the sandy shores, enjoy beachcombing, or embark on a fishing charter to catch salmon and halibut.

2. Kincaid Park Beach

Situated in Anchorage, Kincaid Park Beach offers panoramic views of Cook Inlet and the Alaska Range. This scenic beach is perfect for picnicking, beach volleyball, and kite flying, with miles of sandy coastline to explore.

3. Halibut Point Recreation Area

Halibut Point Recreation Area, located near Sitka, features a beautiful sandy beach overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Visitors can enjoy swimming, sunbathing, and beachcombing, with opportunities to spot whales, sea lions, and otters offshore.

4. Anchor Point Beach

Anchor Point Beach, located on the Kenai Peninsula, is known for its stunning views of the Cook Inlet and the Aleutian Range. This pristine beach is a popular spot for fishing, clamming, and wildlife viewing, with opportunities to see bald eagles and migratory birds.

5. Ninilchik Beach

Ninilchik Beach, nestled between Homer and Kenai, offers breathtaking views of Cook Inlet and the Chigmit Mountains. Visitors can enjoy beachcombing, picnicking, and birdwatching, with opportunities to see beluga whales and seals offshore.

6. Sitka's Silver Bay Beach

Silver Bay Beach, located near Sitka, is a hidden gem known for its tranquil setting and pristine shoreline. Visitors can relax on the sandy beach, explore tide pools, and admire stunning views of the surrounding mountains and forested coastline.

7. Kachemak Bay State Park

Kachemak Bay State Park, near Homer, offers miles of pristine coastline, rugged cliffs, and secluded beaches. Visitors can hike along scenic trails, kayak through tranquil waters, and camp under the stars, surrounded by the beauty of Alaska's wilderness.

8. Seward Waterfront Park

Seward Waterfront Park, located in the picturesque town of Seward, offers stunning views of Resurrection Bay and the surrounding mountains. This scenic beach is perfect for beachcombing, birdwatching, and watching cruise ships and fishing boats pass by.

9. Kenai Beach

Kenai Beach, situated on the Kenai Peninsula, offers sweeping views of Cook Inlet and the Kenai Mountains. Visitors can enjoy beachcombing, picnicking, and fishing for salmon and trout, with opportunities to see bald eagles and shorebirds along the shoreline.

10. Bishops Beach

Bishops Beach, located in Homer, is a tranquil retreat known for its scenic beauty and abundant wildlife. Visitors can stroll along the sandy shores, watch for whales and seals offshore, and enjoy stunning views of Kachemak Bay and the surrounding mountains.

In conclusion, Beaches in Alaska are a hidden treasure trove waiting to be discovered. Despite its reputation for icy landscapes, this vast state offers stunning coastal areas that rival those found in more traditional beach destinations. From Homer Spit Beach with its picturesque views of Kachemak Bay to the tranquil retreat of Bishops Beach in Homer, each beach in Alaska has its own unique charm and beauty.

6 notes

·

View notes

Video

I've kayaked near belugas many times up in Alaska, but never on purpose. See, it's illegal to intentionally approach them, and especially illegal to interact with them.

The problem is, the belugas don't know this, and they are very keen to investigate anything they see. So sometimes, you'll just be happily kayaking around the Aleutians, and suddenly a bigass whale just emerged from the depths to study you. In an attempt to comply with the law, you'll paddle away.

Then the beluga will call its friends, and you'll have five enormous and yet tiny whales chasing your little boat, desperate to swim in circles around you and bump you with their large melon-heads and try to goad you into violating state and federal laws, and eventually you'll give up and wait for half an hour until they've finished amusing themselves.

It's magical.

17K notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1783, four decades after Vitus Bering’s first foray along the Aleutian Islands in 1741, Russia established what would become the center of its commercial operations in “Aliaska” on what Russians called Kodiak Island midway along the southern coast. When sea otter numbers again began to drop because of overharvesting in the areas first colonized along the Alaskan peninsula, much as they had in the western reaches of the Pacific Ocean, the Russian American Company (RAC), chartered by the Russian imperial government in 1799 to advance its interests in North America, extended its operations further eastward along that coast. The number of settlements established by the RAC remained relatively small, but it took just two decades for it to extend its commercial activities some two thousand miles along Alaska’s southern coast. In 1794, the RAC established a small commercial settlement at Yakutat Bay and, in 1799, another that it called Arkhangel’sk, rebuilt nearby as Novoarkhangel’sk in 1804 after the first settlement was destroyed by the Tlingit in 1802. [...]

---

Although Russia claimed the region it called Russian America by right of “discovery,” as the concept was understood in European international law at the time, its geographical contours remained largely unknown. In this sense yet again, the exclusive right to engage in commercial activity granted to the RAC by the Russian imperial government paralleled that granted to the HBC a century earlier by the British Crown and that granted to the Matsumae clan by the Tokugawa shogunate. Like the shogunate and the British Crown, the Russian imperial government knew almost nothing about most of the territory to which it purported to grant exclusive commercial access.

---

With fewer than nine hundred Russian employees in all of Russian America at any given time, the RAC’s efficient exploitation of fur-bearing mammals in the region relied largely on the coerced labor first of the Aleut and then of the Kodiak peoples who had hunted along the Alaskan coast for centuries. It was their knowledge of land and ocean and the creatures that inhabited both, as well as their labor and finely honed technologies, that made possible Russia’s success. In his 1824 report, Zavalishin noted that the Kodiak “had dugout canoes whose speed was not inferior to that of the best rowboats or even whaleboats and gigs of English construction” and that they were not afraid to take either these or their small skin umiaks out on the open ocean. The Aleut, he reported, “handle[d] their small skin boats as deftly as our Cossacks do horses, [pursuing] game with great speed, turning kayaks easily in all directions, so that the prey rarely manages to escape.”

---

Text by: Andrea Geiger. Converging Empires: Citizens and Subjects in the North Pacific Borderlands, 1867-1945. 2022.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Aleut

The indigenous people of the Aleutian Islands of Alaska and Russia, the Aleuts (Unangan, Unungas) are a group whose traditional territory spans America and Asia.

The Aleut live in partially underground houses known as barabaras, with multiple families living in a single barabara. They remain primarily hunter-gatherer-fisherpeople.

Visual arts of the Aleut include baidarkas (Aleutian kayaks for hunting), weaving, embroidery, and mask making. In particular, masks are used to portray figures from oral history and religion. The masks were carved wood, decorated with paint, feathers, and other natural products.

The Aleut used tattoos and piercings, especially facial markings, for religious and cultural reasons. As people who lived in possibly the harshed climate in the world, the clothing was beautiful and incredibly effective. They used the natural water repulsion of animal skins to create hooded parkas that remain unparalleled for cold, snowy climates.

The first Outside contact with the Aleut was by Russian Orthodox missionaries in the late 18th century.

#history#world history#long post#indigenous history#american history#ancient history#russian history#asian history#russia#aleut#indigenous people#indigenous#native american history#native american#first nations history#national native american heritage month#aleutian#native alaska#native alaskan#Unangan#Unungas

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some puns, via my dad:

1. The fattest knight at King Arthur's round table was Sir Cumference. He acquired his size from too much pi.

2. I thought I saw an eye-doctor on an Alaskan island, but it turned out to be an optical Aleutian.

3. She was only a whisky-maker, but he loved her still.

4. A rubber-band pistol was confiscated from an algebra class, because it was a weapon of math disruption.

5. No matter how much you push the envelope, it'll still be stationery.

6. A dog gave birth to puppies near the road and was cited for littering.

7. A grenade thrown into a kitchen in France would result in Linoleum Blownapart.

8. Two silk worms had a race. They ended up in a tie.

9. A hole has been found in the nudist-camp wall. The police are looking into it.

10. Time flies like an arrow. Fruit flies like a banana.

11. Atheism is a non-prophet organization.

12. Two hats were hanging on a hat rack in the hallway. One hat said to the other: 'You stay here; I'll go on a head.'

13. I wondered why the baseball kept getting bigger. Then it hit me.

14. A sign on the lawn at a drug rehab center said: 'Keep off the Grass.'

15. The midget fortune-teller who escaped from prison was a small medium at large.

16. The soldier who survived mustard gas and pepper spray is now a seasoned veteran.

17. A backward poet writes inverse.

18. In a democracy it's your vote that counts. In feudalism it's your count that votes.

19. When cannibals ate a missionary, they got a taste of religion.

20. If you jumped off the bridge in Paris, you'd be in Seine.

21. A vulture carrying two dead raccoons boards an airplane. The stewardess looks at him and says, 'I'm sorry, sir, only one carrion allowed per passenger.'

22. Two fish swim into a concrete wall. One turns to the other and says, 'Dam!'

23. Two Eskimos sitting in a kayak were chilly, so they lit a fire in the craft. Unsurprisingly it sank, proving once again that you can't have your kayak and heat it too.

24. Two hydrogen atoms meet. One says, 'I've lost my electron.' The other says, 'Are you sure?' The first replies, 'Yes, I'm positive.'

25. Did you hear about the Buddhist who refused Novocain during a root-canal? His goal: transcend dental medication.

26. There was the person who sent ten puns to friends, with the hope that at least one of the puns would make them laugh. No pun in ten did

10 notes

·

View notes

Link

As a poison

The roots of A. ferox supply the Nepalese poison called bikh, bish, or nabee. It contains large quantities of the alkaloid pseudaconitine, which is a deadly poison. The root of A. luridum, of the Himalaya, is said to be as poisonous as that of A. ferox or A. napellus.

Several species of Aconitum have been used as arrow poisons. The Minaro in Ladakh use A. napellus on their arrows to hunt ibex, while the Ainu in Japan used a species of Aconitum to hunt bear. The Chinese also used Aconitum poisons both for hunting and for warfare. Aconitum poisons were used by the Aleuts of Alaska's Aleutian Islands for hunting whales. Usually, one man in a kayak armed with a poison-tipped lance would hunt the whale, paralyzing it with the poison and causing it to drown. Aconitum tipped arrows are also described in the Rig Veda.

It has, albeit rarely, been hypothesized that Socrates was murdered via an extract from an Aconitum species, such as Aconitum napellus, rather than via hemlock, Conium maculatum. Aconitum was commonly used by the ancient Greeks as an arrow poison but can be used for other forms of poisoning. It has been hypothesized that Alexander the Great was murdered via aconite.

1 note

·

View note

Text

adding my fav picture of another waterproof/lifejacket Inuit (related to Aleutian) kayaking suit. I think we should enter our clothes from the chest more often.

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Capítulo 171 : Los Botes de Pieles Siberianos en que Paleo Indios navegaron al Nuevo Mundo

.

Aquí te presentamos Botes hechos con Alguna Madera y Pieles de Animales Marinos. Son Botes de Manufactura reciente, no del Ultimo Máximo Glacial. Pero son Fotos antiguas o Dibujos y Pinturas antiguas en Museos de Rusia, Canadá o Estados Unidos.

Yo creo que los Paleoindios de hace 16,000 Años o mas eran muy INTELIGENTES y hacían unas Embarcaciones iguales o mucho mejores que estas aquí detalladas.

Ver la Página anterior 170 para ver la Gente en sus Etnias Siberianas, Beringianas, Canadienses del Gran Norte o del Océano Glacial Artico.

.

Siguiente : Bote Chukchi

.

.

Siguiente : Bote Eskimo

.

.

NO sería que los Primeros Americanos llegaron de Beringia en Botes como estos que ves aquí ??

.

Mas Eskimos navegando en Mares helados :

.

.

Eskimos con mucho Hielo :

.

.

Siguiente : Mujeres Eskimo en Bote 1938 :

.

Bote doble Koryak :

.

.

Esquema de Bote Koryak :

.

.

Bote Inuit

.

.

Bote Inuit

.

.

*************************

.

Umiak = Es el Bote de los Eskimos y los Inuit, pero aparece en Siberia Oriental y en Alaska. Puede tener Huesos de Ballena, Madera y estar forrado en Pieles.

El Umiak es el Bote para Mujeres, Ancianos y Niños. Los Hombres Machos van en Kayaks en el Convoy acompañando los Umiaks.

.

Umiak de Groenlandia 1767 :

-

.

Umiak en el Artico :

.

Un Umiak por dentro :

.

.

.

The umiak ( Shown below ) was an open boat framed with whale bones and driftwood and covered with seal skins; The umiak was built to lengths permitted by available materials, but typically they held about a dozen passengers, or a half dozen hunters. These were used by the Aleuts to transport game or families island to island, or to occasionally hunt whales or walruses .

The elders of Unalaska Island (Dutch Harbor) 700 miles south-west of Anchorage say their ancestors came from Kamchatka (Now Russia) in boats like this, hopping island to island and setting up villages on the best islands.

.

.

Otro Bote Umiak :

.

.

.

Fuentes de las Imágenes :

.

VII. Koryak Fishing, Hunting, and War http://www.kscnet.ru/ivs/bibl/kor/part2_7.htm

.

. Open skin boats of the Aleutians, Kodiak Island, and Prince William Sound https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/etudinuit/2012-v36-n1-etudinuit0584/1015958ar/

.

Habitantes de las Islas Aleutas http://sites.rootsweb.com/~akahgp/Social/aleut.htm

.

Did Indigenous Arctic Mariners use sailbefore the European contact? Presentation delivered in Trondheim, Norwayon October 2, 2013

.

https://www.academia.edu/20109741/Did_Indigeneous_Arctic_Mariners_use_sail_before_the_European_contact

.

*************************

.

Outing in umiak, 1950s

.

Alaska Film Archives - UAF11.4K subscribersSUBSCRIBEA group of friends and family travel by umiak (traditional skin-covered boats) in the Nome/Seward Peninsula region of Alaska, circa 1950. November is American Indian and Alaska Native Heritage Month, in celebration of the rich heritage of Indigenous peoples throughout the United States (Color/Silent/16mm film).

This sequence contains excerpts from AAF-20052 from the William W. Bacon III collection held by the Alaska Film Archives, a unit of the Alaska and Polar Regions Collections & Archives Department in the Elmer E. Rasmuson Library, University of Alaska Fairbanks. For more information please contact the Alaska Film Archives. During his 50-year career, Alaska cinematographer Bill Bacon (1926- 2017) filmed detailed scenes of historical events and everyday life throughout Alaska.

.

youtube

.

Inuit Umiak by Penn Museum

This is an umiak used by the Inuit (Eskimo) people living on the northcoast of Alaska. Umiaks were used for hunting whales and for traveling long distances with a number of people and their gear. This fine example was collected by William Van Valin around 1913. It is made of a wooden frame tightly covered with walrus hide.

Everything is either sewn or spliced together. Nails were not used because they rust and can cause the skins to tear. The average length of an umiak was about 30 feet with a width about five feet. Some umiaks also had a small mast in the bow with a square sail, usually made from reindeer hide.

The umialik or whaling captain was a man of considerable wealth who could afford to own and maintain an umiak. An umialik achieved his status because of his excellent skills as a hunter, his positive relationship with the spirit world, his entrepreneurial capabilities, and his personal charisma. His following usually included members of his extended family, as well as the families of his six or seven crew members. In exchange for their support and work, the umialik provided them food, clothing, shelter, and goods

.

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Head Start Traditional Foods Preschool Curriculum

Octopus, Seal Garnish Alaska Native Head Start Nutrition Lesson Plan

Published September 6, 2017

Nonprofit creates nutrition curriculum reclaiming and revitalizing Unangan & Unangas culture through education to achieve healthier outcomes for children

ANCHORAGE – On St. George Island about 800 air miles from Anchorage, an abundance of birds, crabs, reindeer, halibut, sea lion and wild plants in the past provided nutritious, hearty meals for the Aleut or Unangan people living here.

Though some of the 13 Alaska Native tribes of the Aleutian and Pribilof Islands like the tribe here still rely on subsistence hunting, modern conveniences such as packaged foods have crept into the Unangan and Unangas diets resulting in unhealthy dietary habits. Rates of diabetes have soared over the years and nearly 40 percent of residents in the region are obese.

The Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association, Inc.(APIA) Head Start Program is addressing this health concern among families through its new Qaqamii}u{: Head Start Traditional Foods Preschool Curriculum, with lessons focusing on healthy eating and sparking interest in traditional foods.

“I’m hoping that this will bring awareness to our communities about how traditional foods have all the necessary nutrients to keep us sustained, and that tradition and our culture are very, very important. It’s vital to who we are as Aleut people or Unangan people in our region,” said Bonnie Kashevarof Mierzejek, APIA Head Start program director, who grew up on St. George eating off the island. APIA is an Anchorage-based nonprofit that assists in meeting the health and safety of the Unangan and Unangas in the Aleutian and Pribilof Islands Region.

The remote rural region is home to some of the most unique and nutritious foods in the world. The curriculum, which will be taught in four communities beginning in September, includes nutrition information on such foods as fish, kelp, marine mammals, reindeer, wild birds, and berries. Recipes include fish spread, seal pot roast, salmonberry cobbler, sea lion meatballs and kelp chips. A nutrition graphic compares the iron content in three ounces of seal meat to the same iron found in pounds of hot dogs or chicken nuggets.

“We wanted to highlight the local foods and their highly nutritious qualities, and communicate this to our younger children in a meaningful and culturally-relevant way,” said Suanne Unger, curriculum co-creator and APIA Wellness Program Coordinator.

Unger said the basis for the curriculum was to fill the gap of relevant, cultural information and highlight recipes and nutritional information about the local foods while incorporating the Unangam tunuulanguage. Podcasts of the pronunciations of the traditional foods are available on APIA’s website.

While current national Head Start nutrition curricula may be applicable in Chicago or even the Navajo Nation, those in the Aleutian and Pribilof region realized that discussions on foods such as cantaloupe and broccoli weren’t quite applicable in their lessons plans since the foods weren’t grown in the region or even available in stores.

Accompanying culturally-relevant nutrition information are activities, such as coloring a salmon, seagull or puffin, or asking a community member to talk about how animal skins were used to create kayaks and boats. Several lessons encourage asking a parent or community member to share a hunting story. The curriculum includes sample teacher letters to families discussing the next lesson and a request for donations of plants or animals to use in recipes prepared in the classroom. Parent letters also encourage participation in the classroom in activities such as teaching a traditional song or dance or helping prepare the foods.

These discussions for preschoolers and their families are vital as contemporary lifestyles and conveniences have impacted traditional ways of life. Access to affordable, fresh, nutritious, and high-quality store foods are limited while traditional local foods are right outside people’s doors.

Traditional foods have such a high nutritional value, Unger said, ‘”and because of the potential for food insecurity in the region it’s vital that people understand the importance of their local traditional foods.”

In addition to eating off the island, Kashevarof Mierzejek remembers constantly being outside growing up even in inclement weather. No TV existed so people gathered at the local movie hall for entertainment and socialization.

“Our 3- to 5-year-olds are being exposed to modern technology like video games and they stay home in front of these games, so it’s hard to get them outside. And they’re sitting there eating junk food—that certainly contributes to obesity as well,” she said. “My hope is that this book will be able to bring awareness and our children will be healthier than they ever were in the last 20 years.”

The curriculum, which was created with a one-year, $40,000 grant from the Notah Begay III Foundation, is an adaptation of a book, Qaqamii}u{: Traditional Foods and Recipes from the Aleutian and Pribilof Islands, written by Unger in 2014 compiled after she searched for a single resource guide on harvesting and cooking methods of traditional foods in the region but discovered none. The NB3 Foundation also awarded the organization an additional $5,000 for digital storytelling.

Olivia Roanhorse, NB3 Vice President of Programming, said the foundation is proud to support this Head Start curriculum as it addresses the traditional and cultural needs unique to the Unangan and Unangas.

“We know when Native American communities take ownership of what works for them, in this case instilling healthier eating habits and lifestyles based on their values and beliefs, healthier outcomes can be achieved,” she said. “By instilling these habits and lifestyles early, APIA and their partners are creating a healthy foundation.”

For more information about the Aleutian and Pribilof Islands Association, Inc., or to view and download the free curriculum and videos on the project, go towww.apiai.org. For more information about the NB3 Foundation, go to www.nb3foundation.org.

#Culturally appropriate curriculum#culturally appropriate nutrition#food#Preschool#Head Start Program#Pre K#children#Head Start Traditional Foods Preschool Program#Alaska

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

1. The fattest knight at King Arthurs round table was Sir Cumference. He acquired his size from too much pi.

2. I thought I saw an eye doctor on an Alaskan island, but it turned out to be an optical Aleutian.

3. She was only a whiskey maker, but he loved her still.

4. A rubber band pistol was confiscated from algebra class, because it was a weapon of math disruption.

5. No matter how much you push the envelope, it'll still be stationery.

6. A dog gave birth to puppies near the road and was cited for littering.

7. A grenade thrown into a kitchen in France would result in Linoleum Blownapart.

8. Two silk worms had a race. They ended up in a tie.

9. A hole has been found in the nudist camp wall. The police are looking into it.

10. Time flies like an arrow. Fruit flies like a banana.

11. Atheism is a non-prophet organization.

12. Two hats were hanging on a hat rack in the hallway. One hat said to the other: You stay here; I'll go on a head.

13. I wondered why the baseball kept getting bigger. Then it hit me.

14. A sign on the lawn at a drug rehab center said: Keep off the Grass.

15. The midget fortune-teller who escaped from prison was a small medium at large.

16. The soldier who survived mustard gas and pepper spray is now a seasoned veteran.

17. A backward poet writes inverse.

18. In a democracy it’s your vote that counts. In feudalism it’s your count that votes.

19. When cannibals ate a missionary, they got a taste of religion.

20. If you jumped off the bridge in Paris, you'd be in Seine.

21. A vulture boards an airplane, carrying two dead raccoons. The stewardess looks at him and says, I’m sorry, sir, only one carrion allowed per passenger.

22. Two fish swim into a concrete wall. One turns to the other and says Dam!

23. Two Eskimos sitting in a kayak were chilly, so they lit a fire in the craft. Unsurprisingly it sank, proving once again that you can’t have your kayak and heat it too.

24. Two hydrogen atoms meet. One says, I’ve lost my electron. The other says Are you sure? The first replies, Yes, I’m positive.

25. Did you hear about the Buddhist who refused Novocain during a root canal?

His goal: transcend dental medication.

0 notes

Text

The Island That Humans Can’t Conquer

Text by Sarah Gilman Photos by Nathaniel Wilder

A faraway island in Alaska has had its share of visitors, but none can remain for long on its shores.

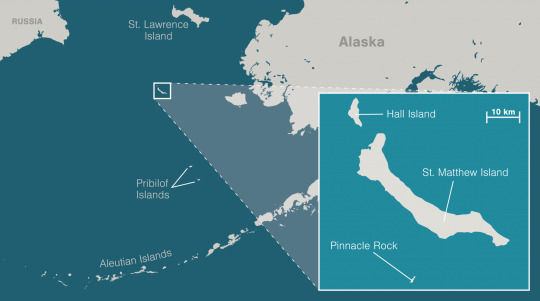

St. Matthew Island is said to be the most remote place in Alaska. Marooned in the Bering Sea halfway to Siberia, it is well over 300 kilometers and a 24-hour ship ride from the nearest human settlements. It looks fittingly forbidding, the way it emerges from its drape of fog like the dark spread of a wing. Curved, treeless mountains crowd its sliver of land, plunging in sudden cliffs where they meet the surf. To St. Matthew’s north lies the smaller, more precipitous island of Hall. A castle of stone called Pinnacle stands guard off St. Matthew’s southern flank. To set foot on this scatter of land surrounded by endless ocean is to feel yourself swallowed by the nowhere at the center of a drowned compass rose.

My head swims a little as I peer into a shallow pit on St. Matthew’s northwestern tip. It’s late July in 2019, and the air buzzes with the chitters of the island’s endemic singing voles. Wildflowers and cotton grass constellate the tundra that has grown over the depression at my feet, but around 400 years ago, it was a house, dug partway into the earth to keep out the elements. It’s the oldest human sign on the island, the only prehistoric house ever found here. A lichen-crusted whale jawbone points downhill toward the sea, the rose’s due-north needle.

Compared with more sheltered bays and beaches on the island’s eastern side, it would have been a relatively harsh place to settle. Storms regularly slam this coast with the full force of the open ocean. As many as 300 polar bears used to summer here, before Russians and Americans hunted them out in the late 1800s. Evidence suggests that the pit house’s occupants likely didn’t use it for more than a season, according to Dennis Griffin, an archaeologist who’s worked on the archipelago since 2002. Excavations of the site have turned up enough to suggest that people of the Thule culture—precursors to the Inuit and Yup’ik who now inhabit Alaska’s northwestern coasts—built it. But Griffin has found no sign of a hearth, and only a thin layer of artifacts.

The Unangan, or Aleut, people from the Aleutian and Pribilof Islands to the south tell a story of the son of a chief who discovered the then uninhabited Pribilofs after he was blown off course. He overwintered there, and then returned home by kayak the following spring. The Yup’ik from St. Lawrence Island to the north have a similar story, about hunters who found themselves on a strange island, where they waited for the opportunity to walk home over the sea ice. Griffin believes something similar may have befallen the people who dug this house, and they sheltered here while waiting for their chance to leave. Maybe they made it, he will tell me later. Or maybe they didn’t: “A polar bear could have gotten them.”

In North America, many people think of wilderness as a place mostly untouched by humans; the United States defines it this way in law. This idea is a construct of the recent colonial past. Before European invasion, Indigenous peoples lived in, hunted in, and managed most of the continent’s wild lands. St. Matthew’s archipelago, designated as official wilderness in 1970, and as part of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge in 1980, would have had much to offer them, too: freshwater lakes teeming with fish, many of the same plants that mainland cultures ate, ample seabirds and marine mammals to hunt. And yet, because St. Matthew is so far-flung, the solitary pit house suggests that even Alaska’s expert seafaring Indigenous peoples may never have been more than accidental visitors here. Others who’ve followed have arrived with the help of significant infrastructure or institutions. None remained long.

I came to these islands aboard a ship called the Tiĝlax̂ [TEKH-lah] to tag along with scientists studying the seabirds that nest on the archipelago’s cliffs. But I also wanted to see what it felt like to be in a place that so thoroughly rejects human presence.

On this, the last full day of our expedition, as the scientists rush to collect data and pack up camps on the other side of the island, the pit house seems a better vantage than most to reflect. I lower myself into the depression, scanning the sea, the bands of sunlight flickering across the tundra on this unusually clear day. I imagine watching for winter’s sea ice, waiting for it to come. I imagine watching for polar bears, hoping they will not. You never know, a retired refuge biologist had said to me before I boarded the Tiĝlax̂. “I would keep my eyes out. If you see something big and white out there, look at it twice.”

Once, these islands were mountains, waypoints on the subcontinent of Beringia that joined North America and Asia. Then the ocean swallowed the land around the peaks, hid them away in thick summer fogs, made them lonely. With no people resident long enough to keep their history, they became the sort of place where “discovery” could be perennial. Lieutenant Ivan Synd of the Russian navy, oblivious to the pit house, believed he was first to find the largest island, in 1766. He named it for the Christian apostle Matthew. Captain James Cook believed he discovered it in 1778, and called it Gore. The whalers who came upon the archipelago later called it, simply, “the Bear Islands.”

Around the winter of 1809–1810, a party of Russians and Unangans decamped here to hunt bears for fur. Depending on what source you consult, many of the Russians died of scurvy, while the Unangans survived, or some or most of the party perished when the sea mammals they relied on moved beyond the range of their hunts, or all were so tormented by polar bears that they had to leave. Indeed, when naturalist Henry Elliott visited the islands in 1874, he found them swarming with bruins. “Judge our astonishment at finding hundreds of large polar bears … lazily sleeping in grassy hollows, or digging up grass and other roots, browsing like hogs,” Elliott wrote, though he seemed to find them less terrifying than interesting and tasty. After his party killed some, he noted that the steaks were of “excellent quality.”

Even after the bears were gone, the archipelago remained a difficult place for people. The fog was endless; the weather, a banshee; the isolation, extreme. In 1916, the Arctic power schooner Great Bear ran afoul of the mists and wrecked on Pinnacle. The crew used whaleboats to move about 20 tonnes of supplies to St. Matthew to set up a camp and wait for help. A man named N. H. Bokum managed to build a sort of transmitter from odds and ends, and climbed each night to a clifftop to tap out SOS calls. But he gave up after concluding that the soggy air interfered with its operation. Growing restless as the weeks passed, men brandished knives over the ham when the cook tried to ration it. Had they not been rescued after 18 days, Great Bear owner John Borden later said, this desperation would have been “the first taste of what the winter would have brought.”

US servicemen stationed on St. Matthew during the Second World War got a more thorough sampling of the island’s winter extremes. In 1943, the US Coast Guard established a long-range navigation (Loran) site on the southwestern coast of the island, part of a network that helped fighter planes and warships orient on the Pacific with the help of regular pulses of radio waves. Snow at the Loran station drifted up to around eight meters deep, and “blizzards of hurricane velocity” lasted an average of 10 days. Sea ice surrounded the island for about seven months of the year. When a plane dropped the mail several kilometers away during the coldest time of year, the men had to form three crews and rotate in shifts just to retrieve it, dragging a toboggan of survival supplies as they went.

The other seasons weren’t much more hospitable. One day, five servicemen vanished on a boat errand, despite calm seas. Mostly, the island raged with wind and rain, turning the tundra to a “sea of mud.” It took more than 600 bags of cement just to set foundations for the station’s Quonset huts.

The coast guard, worried how the men would fare in such conditions if they were cut off from resupply, introduced a herd of 29 reindeer to St. Matthew as a food stock in 1944. But the war ended, and the men left. The reindeer population, without predators, exploded. By 1963, there were 6,000. By 1964, nearly all were gone.

Winter had taken them.

These days, the Loran station is little more than a towering pole anchored by metal cables to a bluff above the beach, surrounded by a wide fan of debris.

On the fifth day of our week-long expedition, several of us walk the sagging remains of an old road to the site. Near the pole that still stands, a second has fallen, a third, a fourth. I find the square concrete pillars of the Quonset huts’ foundations. A toilet lies alone on a rise, bowl facing inland. I pause next to a biometrician named Aaron Christ, as he shoots photos of a pile of rusting barrels that shriek with the scent of diesel. “We’re great at building wondrous things,” he says after a moment. “We’re terrible at tearing them down and cleaning them up.”

And yet, the tundra seems to be slowly reclaiming most of it. Monkshood and dwarf willow grow thick and spongy over the road. Moss and lichen finger over broken metal and jagged plywood, pulling them down.

At other sites of brief occupation, it’s the same. The earth consumes the beams of fallen cabins that seasonal fox trappers erected, likely before the Great Depression. The sea has swept away a hut that visiting scientists built near a beach in the 1950s. When the coast guard rescued the Great Bear crew in 1916, they left everything behind. Griffin, the archaeologist, found little but scattered coal when he visited the site of the camp in 2018. Fishers and servicemen may have looted some, but what was too trashed for salvage—perhaps the gramophone, the cameras, the bottles of champagne—seems to have washed away or swum down into the soil. The last of the straggling reindeer, a lone, lame female, disappeared in the 1980s. For a long time, reindeer skulls salted the island. Now, most are gone. The few I see are buried to their antler tips, as if submerged in rising green water.

Life here grows back, grows over, forgets. Not invincibly resilient, but determined and sure. On Hall Island, I see a songbird nesting in a cache of ancient batteries. And red foxes, having replaced most of St. Matthew’s native Arctic foxes after crossing on sea ice, have dug dens beneath the Loran building sites and several pieces of debris. The voles sing and sing.

The island is theirs.

The island is its own.

The next morning dawns dusky, light and clouds stained sepia by smoke blown from wildfires burning in distant forests. I spot something big and white as I walk across St. Matthew’s flat southern lobe and freeze, squinting. The white begins to move. To sprint, really. Not a bear, as the retired biologist had hinted, but two swans on foot. Three cygnets trundle in their wake. As they turn toward me, I spot a flash of orange porpoising through the grass behind them: a red fox.

The cygnets seem unaware of their pursuer, but their pursuer is aware of me. It veers from the chase to settle a couple of meters away—scraggly, gold eyed, and mottled as the lichen on the cliffs. It drops to its side and rubs luxuriantly against a rock for a few minutes, then springs away in a possessed zigzag, leaving me giggling. After it’s gone, I kneel to sniff the rock. It smells like dirt. I rub my own hair against it, just to say “hey.”

As I continue on, I notice that objects in the distance often appear to be one thing, then resolve into another. Ribs of driftwood turn out to be whale bones. A putrid walrus carcass turns out to be the wave-pummeled rootball of a tree. Unlikely artifacts without stories—a ladder, a metal pontoon—occasionally jag from the ground, deposited far inland, I guess, by storms. When I close my eyes, I have the vague feeling that waves roll through my body. “Dock rock,” someone will call this later: the sensation, after you have spent time on a ship, of the sea carried with you onto land, of land assuming the phantom motion of water beneath your feet.

It occurs to me that to truly arrive on St. Matthew, you have to lose your bearings enough to feel the line between the two blur. Disoriented, I can sense the landscape as fluid, a shapeshifter as sure as the rootball and whale bones—something that remakes itself from mountains to islands, that scatters and swallows signs left by those who pass across.

I consider the island’s eroding edges. Some cliffs in old photos have fallen away or buckled into sea stacks. I look at the few shafts of sun out on the clear water, sepia light touching dark mats of kelp on the Bering’s floor. Whole worlds submerged or pulverized to cobble, sand, and silt, down there. A calving of land into sea, the redistribution of earth into unknowable futures. A good place to remember that we are each so brief. That we never stand on solid ground.

The wind whips strands of hair out of my hood and into my eyes as I press my palms into the floor of the pit house. It feels firm enough, for now. That it’s still visible after a few centuries reassures me—a small anchor against the dragging currents of this place. Eventually, though, I get cold and clamber out. I need to return to my camp near where the Tiĝlax̂ waits at anchor; we’ll be setting course south back over the Bering toward other islands and airports in the morning. But first, I aim overland for a high, gray whaleback of ridge a few kilometers away that I have admired from the ship since our arrival.

The sunlight that striped the hills this morning has faded. An afternoon fog descends as I meander over electric green grass, then climb, hand over hand, up a ribbon of steep talus. I top out into nothingness. One of the biologists had told me, when we first discussed my wandering alone, that the fog closes in without warning; that, when this happened, I would want a GPS to help me find my way back. Mine is malfunctioning, so I go by feel, keeping the steep drop of the ridge’s face on my left, surprised by flats and peaks I don’t remember seeing from below. I begin to wonder if I have accidentally gone down the ridge’s gently sloping backside instead of walking its top. The fog thickens until I can see only a meter or two ahead. Thickens again, until I, too, vanish—erased as completely as the dark tracery of path I left through the grass below soon will be.

Then, abruptly, the fog breaks and the way down the mountain comes clear. Relieved, I weave back through the hills and, on the crest of the last, see the Tiĝlax̂ in the placid bay below. The ship blows its foghorn in a long salute as I lift my hand to the sky.

0 notes

Text

Some puns, via my dad:

1. The fattest knight at King Arthur’s round table was Sir Cumference. He acquired his size from too much pi.

2. I thought I saw an eye-doctor on an Alaskan island, but it turned out to be an optical Aleutian.

3. She was only a whisky-maker, but he loved her still.

4. A rubber-band pistol was confiscated from an algebra class, because it was a weapon of math disruption.

5. No matter how much you push the envelope, it’ll still be stationery.

6. A dog gave birth to puppies near the road and was cited for littering.

7. A grenade thrown into a kitchen in France would result in Linoleum Blownapart.

8. Two silk worms had a race. They ended up in a tie.

9. A hole has been found in the nudist-camp wall. The police are looking into it.

10. Time flies like an arrow. Fruit flies like a banana.

11. Atheism is a non-prophet organization.

12. Two hats were hanging on a hat rack in the hallway. One hat said to the other: ‘You stay here; I’ll go on a head.’

13. I wondered why the baseball kept getting bigger. Then it hit me.

14. A sign on the lawn at a drug rehab center said: 'Keep off the Grass.’

15. The midget fortune-teller who escaped from prison was a small medium at large.

16. The soldier who survived mustard gas and pepper spray is now a seasoned veteran.

17. A backward poet writes inverse.

18. In a democracy it’s your vote that counts. In feudalism it’s your count that votes.

19. When cannibals ate a missionary, they got a taste of religion.

20. If you jumped off the bridge in Paris, you’d be in Seine.

21. A vulture carrying two dead raccoons boards an airplane. The stewardess looks at him and says, 'I’m sorry, sir, only one carrion allowed per passenger.’

22. Two fish swim into a concrete wall. One turns to the other and says, 'Dam!’

23. Two Eskimos sitting in a kayak were chilly, so they lit a fire in the craft. Unsurprisingly it sank, proving once again that you can’t have your kayak and heat it too.

24. Two hydrogen atoms meet. One says, 'I’ve lost my electron.’ The other says, 'Are you sure?’ The first replies, 'Yes, I’m positive.’

25. Did you hear about the Buddhist who refused Novocain during a root-canal? His goal: transcend dental medication.

26. There was the person who sent ten puns to friends, with the hope that at least one of the puns would make them laugh. No pun in ten did

Looking for the best worst Corny Jokes

My friends grandma Loves corny pun jokes

Example: Q: Why can’t bikes stand on their own? A: They are too tired.

help me find more for her to share with her friends on facebook.

78 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Since I had the epoxy outa day am in a paddle state of mind, I took care of the 1st coat on an Aleutian paddle that I laminated and carved last fall. The spine is yellow cedar, with most of the blades being red cedar and the outside edge is Sitka spruce. 1 more coat and then I will varnish the blades a few times and oil finish the center section. #aluetpaddle #kayak #kayakpaddle #cedar #paddlebuilding https://www.instagram.com/p/BxeXvuOjZFF/?igshid=8vgywzjkmb3z

0 notes

Text

Longtime real estate figure Marshall Bennett dies - Crain's Chicago Business

Marshall Bennett, an industry godfather to many of Chicago’s commercial real estate moguls and a pioneer of the modern industrial park, died yesterday of natural causes at his Gold Coast home, according to his daughter Bija. He was 97.

Bennett teamed with Louis Kahnweiler in 1946 and with financial backing from Jay Pritzker launched Centex Industrial Park in the 1950s on 2,250 acres in Elk Grove Village west of O'Hare International Airport. They went on to amass a portfolio of 26 industrial parks around the country, many with airport-side locations that capitalized on the postwar boom in air freight.

“He had the biggest Rolodex of anybody in the industry, and they would be glad to talk to him. Nobody would say no to Marshall,” says Gerald Fogelson, a co-developer of the South Loop residential project Central Station and a benefactor of the Marshall Bennett Institute of Real Estate at Roosevelt University.

Bennett helped raise $11 million to start the school in 2002 as a training ground for real estate professionals. It has graduated about 325 in two master’s degree programs before beginning a bachelor’s program this fall. “He continued to weigh in and check in until a couple of months ago,” says executive director Collette English Dixon.

Bennett and Kahnweiler split in 1982 on good terms, he told Crain’s last year following Kahnweiler’s death at 97. "I wanted to do different things," he said, and those things included diversifying into office brokerage and property management, pension fund advising and syndication.

Goldie Wolfe Miller credits Bennett as being the catalyst for her leaving Rubloff after 20 years to start a real estate brokerage firm in the late 1980s. “He said, ‘Why work for somebody else when you can do it for yourself?’ ” Though Bennett backed her financially, she says, “It wasn’t the money. It was he was there, saying it was the right thing to do.”

On a ski lift at Sun Valley in the 1960s, Bennett had a chance encounter with Steve Wynn, the future casino mogul, and learned they were neighbors at the Idaho resort. According to Bija Bennett, the friendship proved fateful a decade later when Bennett suffered a head injury in a kayaking accident and later was evacuated in a Wynn jet for treatment in Evanston.

“Steve Wynn saved my dad’s life, in my opinion,” she says. Bennett and his wife, Arlene, helped endow a chair in brain surgery at NorthShore Evanston Hospital.

Bennett was born in Hyde Park, grew up in South Shore and graduated in 1941 from the University of Chicago. During World War II he captained a U.S. Navy submarine chaser in the Aleutian Islands.

Another Bennett cause was international relations. He joined the board of the East-West Institute and co-founded the Chicago Ten, a group of Chicago-area Christian, Jewish and Muslim leaders promoting economic-based efforts for Middle East peace.

Services are set for 2 p.m. tomorrow at Congregation Solel in Highland Park.

This story has been updated to correct information pertaining to the degree programs at the Marshall Bennett Institute of Real Estate at Roosevelt University.

Source: https://www.chicagobusiness.com/commercial-real-estate/longtime-real-estate-figure-marshall-bennett-dies

0 notes