#Alawi dynasty

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Rise of Moulay Rashid: Conquest and Consolidation in Morocco

Moulay Ismail Ibn Sharif, a dominant figure in Moroccan history, ruled the country from 1672 to 1727, marking the second reign of the ‘Alawi dynasty. Born in 1645 in Sijilmassa, he was the son of Sharif ibn Ali, the Emir of Tafilalt and the first sovereign of the ‘Alawi dynasty. His lineage traced back to Hassan Ad-Dakhil, a 21st-generation descendant of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Notably, his…

View On WordPress

#African History#Alawi dynasty#Battle of Angad#Morocco#Morocco history#Moulay Ismail Ibn Sharif#north african culture#North African History

0 notes

Text

29th January 1850 saw the birth in Muthill of Helen Gloag, who through a series of remarkable events went on to become the Empress of Morocco.

If you have not heard of Helen Gloag, a Scottish woman who became Sultana of Morocco, you are not alone. Her story recently resurfaced.

Helen, a traditional Scottish redhead, was the eldest of Andrew and Anna’s four children. Tragically, Anna lost her mother when she was a child, and her father remarried. Her relationship with her new stepmother was said not to be very good, and as a result, Helen left home when she was just 19-years-old in May 1769 to travel as an indentured servant to the New World – the British colony of South Carolina to be specific.

Helen, who was travelling with some female friends, would not make it to the New World. After sailing for just two weeks, her ship was attacked off the coast of Spain by the Barbary pirates from Morocco. Along with the other women, Helen was taken to a slave market in Algiers in what is today Algeria. The men on the ship were all murdered.

The beautiful green-eyed Scottish woman was sold to a wealthy Moroccan who then handed her over to Sultan Sidi Mohammid ibn Abdullah of Morocco (a member of the Alaouite/Alawi Dynasty that still rules Morocco to this day) as a gift. Due to her beauty, the Sultan added her to his harem. Before long, she became his fourth wife and would go on to be the principal wife who was given the title of Sultana of Morocco.

She was called Lalla Zahra; ‘Lalla’ is a term used in Morocco, ahead of the person’s given name, to show respect and is often used by noble and royal women.

Reportedly, the Sultana was instrumental in convincing the Sultan to have seafarers and slaves, who had been captured by pirates, released. As a favourite of his, she was able to write and send gifts back home to Scotland; the Sultan, who was the first head of state to recognise the United States, even allowed her brother, Robert, to visit her in Morocco on occasion. Robert was responsible for her story being brought back to her homeland.

Sultan Sidi Mohammid died in 1790, and one of his sons, by a German woman in his harem, Yazid took the throne to become Sultan of Morocco. Not wanting to have any competition for the throne, he ordered the killing of his two brothers, who he is said to have been incredibly envious of, by Helen – even though she had attempted to keep them safe by sending them away to a monastery in Tétouan (a town where his first order of business was to persecute the Jews). She reportedly sent out a plea to the British Navy for assistance, but they would not make it to her sons before the new Sultan’s troops would discover and murder both boys.

What exactly happened to the Scottish Sultana of Morocco has never been clear, as nothing was heard from or about her after the death of her sons; however, it has been assumed that she was killed by Yazid or his forces in the two years – known to be full of unrest – after he took the throne.

As I said at the start interest in Helen Gloag only recently peaked thanks to a historical novel based upon her, The Fourth Queen by Debbie Taylor

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Morocco

General Information Morocco is a country in Northern Africa. The region has been traditionally inhabited by Berber/Amazigh peoples, in ancient times it was part of Carthage and later the Roman Empire. In the late 7th century, it was conquered by Arabs. In 1912, Morocco became a French protectorate, in 1956, it regained independence. Since the 17th century, the ‘Alawi dynasty has been ruling over Morocco. Most of the 36.5 Million inhabitants are Muslim. The official languages are Arabic and Tamazight, the capital is Rabat.

The Oldest Continually Operating University The University of Karueein is the oldest continually operating university in the world. It was founded in 859 AD. ~ Anastasia Economy The economy of Morocco is considered a relatively liberal economy, governed by the law of supply and demand. Since 1993, Morocco has followed a policy of privatization of certain economic sectors which used to be in the hands of the government. Morocco has become a major player in African economic affairs, and is the 5th largest African economy by GDP (PPP). The World Economic Forum placed Morocco as the 1st most competitive economy in North Africa, in its African Competitiveness Report 2014–2015.

~ Damian

Sources: https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/oldest-university https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economy_of_Morocco https://www.britannica.com/place/Morocco

0 notes

Text

Separatist and irredentist movements in the world

Rif

Proposed state: Republic of the Rif

Region: Rif, Morocco

Ethnic group: Rifians

Goal: independence

Date: 1921

Political parties: -

Militant organizations: Rif Independence Movement (RIM)

Current status: inactive

History

11th century BCE - Phoenician trading posts

814-146 - Carthaginian Empire

145 - the Rif becomes part of the Roman Empire

5th century CE - Vandal control

6th century - Byzantine Empire

661-750 - Umayyad Caliphate

710-1019 - Emirate of Nekor

1040-1147 - Almoravid Empire

1121-1269 - Almohad Caliphate

1244-1465 - Marinid Sultanate

1472-1554 - Wattasid dynasty

1510-1659 - Saadi Sultanate

1631-present - ‘Alawi dynasty

1912-1956 - French and Spanish protectorates in Morocco

1921-1926 - Rif Republic

1958-1959 - Rif revolt

2013 - reinvigoration of the RIM

The Rif has been inhabited by the Imazighen (Amazigh people) since prehistoric times. It has been a part of the Phoenician, Carthaginian, and Roman empires and was briefly under Vandal control.

The Emirate of Nekor was founded in 710 and Imazighen started converting to Islam. This was followed by a series of Amazigh dynasties between the 11th and 16th centuries and two Arab dynasties from the 16th century until the present day.

In 1912, France and Spain established two protectorates in Morocco. The majority of the Rif region was under Spanish rule until 1956, except between 1921 and 1926, when the Republic of the Rif was established as an independent state from Spanish occupation and the Alawite sultan. It was during this time that the RIM was founded.

After Morocco’s independence in 1956, Rifians rose to protest against the government’s marginalization and neglect of the Rif. After the Arab Spring, the RIM was revitalized, but no further steps have been taken toward independence.

Rifian people

There are around 7.5 million Rifians. They mainly live in Morocco, but can also be found in Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Spain.

They speak Tarifit, an Amazigh language of the Afro-Asiatic family, and practice Sunni Islam but retain some pre-Islamic traditions.

The Rifians are divided into several tribal groups and organize themselves patrilineally. They mostly live an agricultural lifestyle and some practice fishing.

Vocabulary

ⴰⵔⵔⵉⴼ (Arrif) - Rif

Irifiyen - Rifians

Iweṭṭasen - Wattasid dynasty

Izigzawen - Greens (PDA)

Tagduda en Arrif - Republic of the Rif

ⵜⴰⵔⵉⴼⵉⵢⵜ (Tmaziɣt) - Tarifit

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In Game:

Masyaf was an isolated mountain municipality, located in the Orontes Valley in western Syria among the An-Nusayriyah Mountains. For a long time, it served as a base of operations for the Assassin Order during the High Middle Ages, but fell into disrepair after the Mongol siege of 1257. By the early 16th century, it was temporarily occupied by Byzantine Templars.

The fortress of Masyaf was established in 1162 as an Assassin base by a man who would later be popularly known by his title of Al Mualim (real name Rashid ad-Din Sinan). He was sent from Alamut to establish the fortress by Hassan the Younger, the leader of the Levantine Brotherhood at the time. While ostensibly, this was a command by Hassan to cultivate Assassin influence in the Levant, rumors circulated as to the exact reason. Some Assassins believed that there had been a schism between the two owing to ideological differences, with Al Mualim leaving to create his own independent Assassin Order entirely. There were even whispers that Al Mualim was motivated not merely by a desire for independence, but power lust, an ambition to act as a king on his own, without the influence of Hassan.

Saladin, a Sultan of the Ayyubid dynasty of Egypt and Syria and also the commander of the Muslim armies united against the invading armies of Europe, under Richard the Lionheart during the Third Crusade, attacked the fortress, hoping that he could prevent the assassins from making a successful attempt on his life. On the second night of the siege, Master Assassin Umar Ibn-La'Ahad infiltrated the Sultan's tent and left a knife in Saladin's sleeping pallet. However, Saladin awoke and raised the alarm, and Umar was forced to kill a Saracen nobleman during his escape. Saladin agreed to leave, but not before he demanded that Umar be beheaded for his murder of the Saracen nobleman.

In 1189, Masyaf was attacked again, though this time by Templar Crusaders after one of their agents infiltrated the ranks of the Assassin Order; the fortress was captured by the Crusaders, after which Al Mualim was held hostage. As a result, a battle between the two forces raged on in the village, however, through the efforts of the Assassin Altaïr Ibn-La'Ahad, the fortress was reclaimed and Al Mualim saved. With the fortress recaptured, the Assassins were able to drive the Templars from Masyaf.

Al Mualim came into possession of an Apple of Eden in 1191 after it was retrieved by Malik Al-Sayf from Solomon’s Temple. The Templars that also sought the Apple, including Grand Master Robert de Sablé, followed Malik’s blood trail back to Masyaf and attacked, hoping to regain the Apple. Altaïr helped to spring a trap on the Templars, crushing them with falling logs, forcing them to retreat.

Later that same year, Al Mualim used the Apple to enslave the citizens of Masyaf. Altaïr was able to stop him by murdering his former teacher and reclaim the Apple. After Al Mualim’s death, Abbas Sofian attempted to take the Apple for himself, but was also defeated by Altaïr.

Sometime before 1227, Abbas staged a coup d'état and was able to take over the Order. Losing control of the Assassins in Syria, and after the death of Altaïr’s wife, Maria Thorpe, and Malik, Altaïr fled the city, and entered a self-imposed exile. Abbas reigned for twenty years before Altaïr returned and murdered Abbas with the newly invented hidden gun.

Masyaf was abandoned around a decade later. Altaïr had constructed a library, compiling the information he had learned from the Apple, but he sent his Niccolò and Maffeo Polo, who were guests of the Order, invited by Altaïr's eldest son, Darim, away with the books and the memory seals to his library. Altaïr then took the Apple that Malik had retrieved from the Temple so many years ago and locked himself in his now empty library where he died at the age of ninety-two.

Ezio Auditore da Firenze managed to get to Masyaf a few centuries later to find that it had been overrun with Byzantine Templars. After killing their leader and retrieving all of the Masyaf Keys, Ezio returned to Masyaf in 1512 with Sofia Sartor entered the library to find that it was empty save for Altaïr’s skeleton and his Apple of Eden.

In Real Life:

Masyaf castle ( قلعة مصياف) is located in the town of Masyaf in Hama Governorate, Syria, situated in the Orontes Valley, approximately 40 kilometers to the west of Hama. It served to protect the trade routes to cities further inland such as Banyas. The castle itself stands on a limestone platform about 20 meters above the surrounding plain and was likely built around the time of the Byzantine Empire.

The citadel became famous as the stronghold from which Rashid ad-Din Sinan, known as the Old Man of the Mountains ruled. He was a leader of the Syrian wing of the Hashshashin sect, also known as the Assassins, and a figure in the history of the Crusades. A trained Hashshashin himself and a powerful Northern Syrian warlord, Sinan controlled and ruled over the trained killers.

Although the original castle itself was Byzantine in origin, levels were added by the Nizari Ismailis, Mamluks, and Ottomans. The castle was captured by the Assassins in 1141 from Sanqur (who had held it on behalf of the Banu Mundiqh of Shayzar) and was later refortified by the Mentor of the Assassins.

(Image Source)

It was from this fortress that Rashid ad-Din Sinan ordered his assassins to take out several different targets, such as the King of Jerusalem and Saladin, the leader of the Saracen army. Fearing for his life, Saladin leid seige to the fortress in attempt to kill Sinan.

According to legend, an assassin snuck into Saladin’s tent during his seige. Some accounts say that he left a dagger and a note. Others say that a poisoned cake was left, but the note said something to the effect of “You are in our power.” Although Saladin had defeated Crusader castles with much stronger defenses, the intimidation worked, and Saladin arranged a peace negotiation with Sinan.

In 1260 A.D., Masyaf and three other Assassin fortresses surrendered to the invading Mongols. However, the Mongol victory was short-lived as they were defeated by the Mamelukes at the Battle of ‘Ayn Jalut in the same year. Once the Mongols were expelled from Syria, some sources say that the Assassins were back in control of Masyaf. Ten years later, the Mamelukes under their sultan, Baibars, took control of Masyaf. Whilst the Assassins eventually disbanded, the castle remained a part of the landscape.

Masyaf, along with the rest of Syria, was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire in 1516 and 1517, after the Ottoman victory over the Mamluks at the Battle of Marj Dabiq. Masyaf became a part of the liwa (district) of Homs, and along with the other Ismaili fortresses in its vicinity (qala' al-da'wa), was responsible for paying a special tax. The town had a khan which paid tolls to the Ottoman authorities. The tolls were abolished later in the mid-16th century. According to the Sufi traveler Abd al-Ghani al-Nabulsi, the emir of Masyaf in the early 1690s was a descendant of the Arab Tanukh tribe named Sulayman.

In 1703, the Raslan clan, an Alawite tribe, took over Masyaf and controlled it for about eight years until it was restored to the Ismailis following the intervention of the Ottoman authorities. In 1788, the emir of Masyaf, Mustafa ibn Idris, built a sabil (ablutions fountain) and a house that would be used by himself and successive Ismaili emirs.

In 1808, the Raslan clan led by Sheikh Mahmud Raslan attacked Masyaf, killing its Ismaili chief, Mustafa Milhim, and his son, and captured the fortress. About 300 of the town's Ismaili inhabitants were also killed, while many others, including a Dai, fled for Homs, Hama and other areas in central Syria, settling in those places temporarily.

(Image source)

In modern times, conversion work began in an attempt to preserve the fortress, beginning in the year 2000. Part of this conversion and restoration project involves uncovering chambers and passageways used by the assassins in addition to ceramics and coins, in an attempt to learn more about not only Rashid ad-Din Sinan himself, but also the order he ran.

Sources:

http://www.reuters.com/article/us-syria-castle-assassins-idUSL1114464920070713

http://www.ancient-origins.net/ancient-places-asia/masyaf-castle-seat-assassins-001888

http://www.atlasobscura.com/places/castle-of-musyaf

https://books.google.com/books?id=qXG6AAAAIAAJ&q=Masyaf+Ismaili+Alawi&dq=Masyaf+Ismaili+Alawi

https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/uploads/Documents/pubs/PolicyFocus132_Heras4.pdf

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

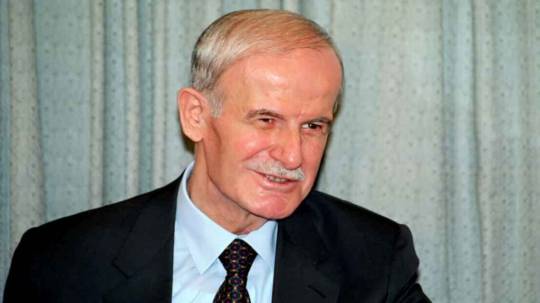

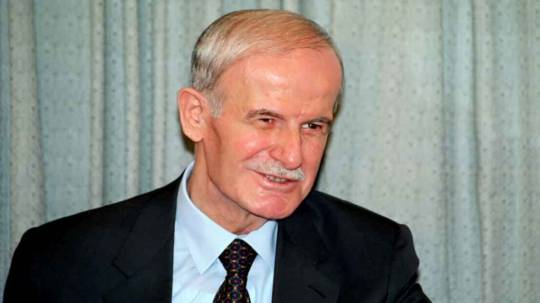

Hafez al-Assad Biography and Profile

New Post has been published on https://www.politicoscope.com/hafez-al-assad-biography-and-profile/

Hafez al-Assad Biography and Profile

Born in the village of Qardaha in Syria on October 6, 1930, Hafez al-Assad became Syrian president of the country in 1971, after taking part in multiple coups. Though widely criticized for brutal tactics (most notably the 1982 Hama massacre), he is also praised for bringing stability to Syria, and for improving relations between Syria and Western powers by supporting America in the Persian Gulf War. He served as president of Syria until his death on June 10, 2000.

Of the five members of the Ba’ath Party’s Military Committee who seized power in Syria in 1963, Hafez Al-Assad went the furthest. Of the other four, one took the blame for Syria’s loss of the Golan Heights during the Six Day War and was pushed out of politics; one committed suicide; a third was assassinated; the other died in prison after 25 years.

Assad was born into a modest family in Qurhada in Syria’s north-western mountains, a village which was said to be 10 kilometres from the nearest road. He went to school in Latakia at a time when less than a quarter of Syrian children received an education. According to Patrick Seale’s unofficial biography, Asad of Syria: The Struggle for the Middle East, he inherited his father’s love of books, poetry and Arabic language.

Much has been made of the Assad family’s Alawi background and what it means to have members of a minority Shia Muslim sect rule over a predominantly Sunni Muslim country. Assad senior did not surround himself entirely by other Alawites, though; amongst those associates whom he kept close was a Palestinian Christian speechwriter and a Palestinian soldier who was his bodyguard. His foreign minister, chief aide and first three prime ministers were Sunni Muslims. Ultimately, the military was where a number of Assad’s loyal contacts and alliances lay. After joining the military academy in Homs, Assad joined the flying school at Aleppo, graduating into the air force in his early twenties.

In the period between France’s exit of the country in 1946 and Hafez Al-Assad becoming president a number of coups rocked Syria. Hence, Assad’s arrival on the scene (what he labelled the “corrective movement”) and his ability to hold power for the next thirty years is regarded by most observers as characteristic of one of his strengths – stability. He also set about portraying himself as a man of the people by visiting remote provinces of the country and talking to the people who lived there. According to Seale, he would bring back “sackfuls” of complaints for his staff to deal with.

Perhaps one of the most defining moments, or losses, in Hafez Al-Assad’s life was the Six Day War with Israel in which Syria lost the Golan Heights. He believed that this defeat could be overturned and Syria’s position vis-a-vis Israel became the vanguard of his presidency. His image as an Arab leader willing to confront Israel was confirmed on 6 October 1973 when his forces attacked the occupying Israeli forces in the Golan Heights; at the same time, taking such a stand isolated him. His co-belligerents Egypt and Jordan went on to sign separate peace treaties with Israel.

To face Israel Assad needed friends and so he moved Syria closer to the Soviet Union. As Patrick Seale recognises, though, “he grasped early on that the Soviet Union’s friendship for the Arabs would never match the United States’ generous, sentimental and open-handed commitment to Israel.” Israel’s presence was particularly unsettling for a region that had been under the control of both the Europeans and the Ottoman Empire within living memory.

Assad was known to be an ardent supporter of the Palestinian cause, but his involvement in the Lebanese civil war tarnished this reputation immensely. The “red-line” agreement saw the White House issue support for Syria to take a constructive role in the civil war; the chief architect of the agreement, then Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, felt that if Assad could be tempted to crush the Palestinians in order to prevent an Israeli attack on Lebanon it would discredit the Syrian leader and curb Soviet power.

It worked. Assad sent in troops, sieges were broken and Palestinians were massacred. Whilst Assad’s relationship with the Palestinians and the Soviet Union took a severe blow, Israel’s relations with Lebanese Christians were strengthened.

Following Assad’s intervention in Lebanon in 1976 there was a series of explosions and assassinations in Syria, many of which were attributed to the Muslim Brotherhood. On 16 June 1979, Alawite officer cadets were assembled in the dining hall of the Aleppo Artillery School when gunmen opened fire on them, killing up to 83. Assassins targeted members of the government and prominent Alawites.

Internally, Assad’s biggest threat came from the Brotherhood. In retaliation for an assassination attempt on Assad in 1980 his brother Rifaat led the Defence Brigades in committing the Tadmor Prison massacre; 1,000 prisoners were killed. The notorious prison was known for holding many members and supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood. The crackdown on the group reached its apogee in 1982 in Hama. Regime soldiers rolled into the city and spent three weeks massacring the residents before the air force was sent in to finish off the job. Tens of thousands were killed, mosques were flattened and whole neighbourhoods were destroyed.

The ability to crush opposition to his rule was a prominent theme throughout Assad’s presidency. He had succeeded in eliminating other members of the Military Committee, tried to wipe out the Brotherhood and would later banish his brother Rifaat when he suspected that he was moving closer to his own position as president. Yet, despite his opposition to Israel and the west also being a presidential norm for Hafez Al-Assad, Syrian troops were sent to fight in the 1990 Gulf War on the American side. It is claimed that he went on to conduct peace talks with Israel, which stalled thanks to Tel Aviv’s refusal to give back the Golan Heights.

During his 30 years in power Assad cut basic food prices in Syria and built schools, hospitals, roads, damns and railways. The economy grew with foreign aid reaching £600 million from a starting point of £50 million. At the same time, he established an authoritarian state, curtailed freedom of speech and secured his tenure with 99 per cent “yes” referendums. He was Chief Judge, gave himself the power to dissolve parliament and permitted civilians to be tried in military courts and tortured in secret prisons.

Hafez Al-Assad died on 10 June 2000. His eldest son Basil was a lieutenant colonel in the military and was being groomed to take over as president when he was killed in a car crash on 21 January 1994. Basil’s brother, Bashar, was recalled from London where he was training as an ophthalmologist and pushed through the military in preparation to take over as head of the Assad dynasty; Bashar remains at the helm in Damascus to this day.

Hafez al-Assad Biography and Profile (Biography / Middle East Monitor / Politicoscope)

#Ba'ath Party#Ba'ath Party Congress#Bashar al-Assad#Biography and Profile#Hafez al-Assad#Hafez al-Assad Biography and Profile#Syria

0 notes

Text

You're definitely not ready to hear about muslim ruler's children

(Spoiler alert : sultan ismail of the early alawi dynasty had like 500 children and when our history teacher told us this the class exploded with awe)

i’ll never get over how much the real ramesses fucked. like shit dude STOP

8K notes

·

View notes

Photo

@avipopoki Any Christian who believes that was clearly sleeping through history class, yes. But it seems you were too, if you genuinely believe what you wrote. For starters, no one is “really kind” when taking over land. I’m surprised that has to be said out loud. They did not “respect” my religion; we actually did have to pay the tax. It was pay the tax, convert, or die. That tax was called the jizya. The jizya allowed us to continue to practice our religions, but it nonetheless required non-Muslim communities to pay for the Islamic expansion in a way that Muslims did not have to. And, as an expression of the supremacy of Islam over conquered religions, it very much was a source of humiliation. As a general rule, Jewish people fared better under Muslim rule than under Christian rule. But that speaks about the violent oppression of Christian rulers (especially post-Crusades) than it does about the “tolerance” of Muslim rulers. Like traditional Christianity, traditional Islam has never held tolerance (in the sense that we understand it today) to be a virtue. In Muslim lands, we coexisted. Friendly partnerships were made. Genuine friendships formed. But we were not equal. And even these periods of relative peace were interrupted by dynasties like the Almohads and the Almoravids. Even under periods of peace, Christians and Jews had to wear items that distinguished themselves from the Muslim populace. In some cases, this was encouraged by Christians and Jews in order to keep religious boundaries clear. At other times, this was extremely taxing on minority populations. Christians were considered People of the Book, but simultaneously treated as pagans and thus regulated to the outskirts of cities and towns. There was at least one legal ruling in Damascus during the early modern period that, in the case of disasters in which Muslim and non-Muslim people were killed and there was no way to distinguish between the corpses, prayers weren’t allowed to be said over any of them out of fear that they might accidentally bless a non-Muslim. The Ottomans? The Ottomans were a large, multi-ethnic state. At some points, rules were very lax. At other points? Things were absolutely miserable. There are reasons that there were Messianic movements aimed at toppling the Caliphate as early as the 17th Century. One only needs to remember the oppression the ‘Alawis, who the Ottomans repeated attempted to forcibly convert to Sunni Islam, and who were not allowed to testify in court. And the Janissaries? Do I even have to go there? Much like Christianity, Islam spread its religion by force (sometimes) or intense pressure (most of the time). Much like Christendom, Dar al-Islam oppressed ethnic and religious minorities within its expanding borders. Much like Christian imperialists, Muslim imperialists committed occasional acts of genocide and appropriated from other cultures. At the same time, there were periods where there were greater levels of “toleration.” Emperor Akbar of the Mughal dynasty abolished the jizya; non-Muslim subjects would not have to pay that tax until his grandson, Aurangzeb, reestablished it. Likewise, bishops in Germanic cities like Mainz and Worms invited Jews into their cities as traders and created contracts to keep them safe. Yet they could not be protected in the wake of angry Crusaders stomping through the Rhineland. Ruling classes practicing my religion were by no means perfect. Ruling classes practicing yours weren’t either. You can sit down now.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

29th January 1850 saw the birth in Muthill of Helen Gloag, who through a series of remarkable events went on to become the Empress of Morocco.

If you have not heard of Helen Gloag, a Scottish woman who became Sultana of Morocco, you are not alone. Her story recently resurfaced.

Helen, a traditional Scottish redhead, was the eldest of Andrew and Anna’s four children. Tragically, Anna lost her mother when she was a child, and her father remarried. Her relationship with her new stepmother was said not to be very good, and as a result, Helen left home when she was just 19-years-old in May 1769 to travel as an indentured servant to the New World – the British colony of South Carolina to be specific.

Helen, who was travelling with some female friends, would not make it to the New World. After sailing for just two weeks, her ship was attacked off the coast of Spain by the Barbary pirates from Morocco. Along with the other women, Helen was taken to a slave market in Algiers in what is today Algeria. The men on the ship were all murdered.

The beautiful green-eyed Scottish woman was sold to a wealthy Moroccan who then handed her over to Sultan Sidi Mohammid ibn Abdullah of Morocco (a member of the Alaouite/Alawi Dynasty that still rules Morocco to this day) as a gift. Due to her beauty, the Sultan added her to his harem. Before long, she became his fourth wife and would go on to be the principal wife who was given the title of Sultana of Morocco.

She was called Lalla Zahra; ‘Lalla’ is a term used in Morocco, ahead of the person’s given name, to show respect and is often used by noble and royal women.

Reportedly, the Sultana was instrumental in convincing the Sultan to have seafarers and slaves, who had been captured by pirates, released. As a favourite of his, she was able to write and send gifts back home to Scotland; the Sultan, who was the first head of state to recognise the United States, even allowed her brother, Robert, to visit her in Morocco on occasion. Robert was responsible for her story being brought back to her homeland.

Sultan Sidi Mohammid died in 1790, and one of his sons, by a German woman in his harem, Yazid took the throne to become Sultan of Morocco. Not wanting to have any competition for the throne, he ordered the killing of his two brothers, who he is said to have been incredibly envious of, by Helen – even though she had attempted to keep them safe by sending them away to a monastery in Tétouan (a town where his first order of business was to persecute the Jews). She reportedly sent out a plea to the British Navy for assistance, but they would not make it to her sons before the new Sultan’s troops would discover and murder both boys.

What exactly happened to the Scottish Sultana of Morocco has never been clear, as nothing was heard from or about her after the death of her sons; however, it has been assumed that she was killed by Yazid or his forces in the two years – known to be full of unrest – after he took the throne.

As I said at the start interest in Helen Gloag only recently peaked thanks to a historical novel based upon her, The Fourth Queen by Debbie Taylor https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/343128.The_Fourth_Queen

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Discovering the world

Morocco 🇲🇦

Basic facts

Official name: المملكة ال��غربية (al-Mamlakah al-Maghribīyah)/ⵜⴰⴳⵍⴷⵉⵜ ⵏ ⵍⵎⵖⵔⵉⴱ (Tageldit n Lmeɣrib) (Arabic/Tamazight) (Kingdom of Morocco)

Capital city: Rabat

Population: 37.7 million (2023)

Demonym: Moroccan

Type of government: unitary parliamentary semi-constitutional monarchy

Head of state: Mohammed VI (Monarch)

Head of government: Aziz Akhannouch (Prime Minister)

Gross domestic product (purchasing power parity): $385.33 billion (2023)

Gini coefficient of wealth inequality: 40.3% (medium) (2015)

Human Development Index: 0.698 (medium) (2022)

Currency: Moroccan dirham (MAD)

Fun fact: It is home to the oldest university in the world.

Etymology

The country’s English name comes from the Spanish name, Marruecos, which derives from the city of Marrakesh. The Arabic name al-Maghrib means “the land of the sunset/the west”.

Geography

Morocco is located in North Africa and borders the Mediterranean Sea and Spain to the north, Algeria to the east, and Western Sahara to the south.

There are six main climates: hot-summer Mediterranean in the northwest, cold steppe in the northeast and west, cold desert in the northeast, hot steppe in the west, warm-summer Mediterranean in the center, and hot desert in the south. Temperatures range from 2 °C (35.6 °F) in winter to 38 °C (100.4 °F) in summer. The average annual temperature is 14.5 °C (58.1 °F).

The country is divided into twelve regions (jihāt), which are further divided into 62 provinces (ạlmuqāṭaʿātu) and thirteen prefectures (ạlmuḥāfaẓātu). The largest cities in Morocco are Casablanca, Fez, Tangier, Marrakesh, and Salé.

History

6400-550 BCE: Cardium Pottery culture

2800-1800 BCE: Bell Beaker culture

800-300 BCE: Phoenicia

5th century-3rd century BCE: Carthaginian Empire

3rd century BCE-40 CE: Amazigh kingdoms

25 BCE-430 CE: Roman Empire

534-661: Byzantine Empire

661-750: Umayyad Caliphate

710-1019: Emirate of Nekor

740-743: Amazigh Revolt

744-1058: Barghawata Confederacy

756-929: Emirate of Córdoba

757-976: Emirate of Sijilmasa

788-974: Idrisid dynasty

929-1031: Caliphate of Córdoba

1060-1147: Almoravid dynasty

1121-1269: Almohad Caliphate

1232-1492: Emirate of Granada

1244-1465: Marinid Sultanate

1472-1554: Wattasid dynasty

1510-1659: Saadi Sultanate

1627-1668: Bou Regreg Republic

1637-1668: Zawiya Dilaʾiya

1666-1912: Alawi Sultanate

1844: Franco-Moroccan War

1859-1860: Hispano-Moroccan War

1905-1906: Tangier Crisis

1911: Agadir Crisis

1912-1956: French protectorate; Spanish protectorate

1921-1926: Republic of the Rif

1953: Revolution of the King and the People

1956-present: Kingdom of Morocco

1963-1964: Sand War

2002: Perejil Island crisis

2003: Casablanca bombings

2011: Marrakesh bombing

2011-2012: protests

2016-2017: Hirak Rif Movement

2018: Moroccan boycott

2021: Morocco-Spain border incident

Economy

Morocco mainly imports from Spain, China, and France and exports to Spain, France, and India. Its top exports are tomatoes, fertilizers, and fruit.

It has oil and phosphate reserves. Services represent 36% of the GDP, followed by industry (19.2%) and agriculture (14.7%).

Morocco is a member of the African Union, the Arab League, the Arab Maghreb Union, the Community of Sahel-Saharan States, and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation.

Demographics

Arabs represent 67% of the population, Imazighen 31%, and Sahrawis 2%. The main religion is Islam, practiced by 99.6% of the population, 99.2% of which is Sunni.

It has a negative net migration rate and a fertility rate of 2 children per woman. 64.6% of the population lives in urban areas. Life expectancy is 73.6 years and the median age is 29.1 years. The literacy rate is 73.8%.

Languages

The official languages of the country are Arabic and Tamazight. Moroccan Arabic is spoken by 91.2% of the population, Hassaniya Arabic by 0.8%, and Tamazight by 7.9%. French is spoken by 32% and Tashelhit by 14.1%.

Culture

Morocco is a blend of Amazigh and Arab cultures with French and Spanish influences. Traditional elements of artistic expression include architecture, calligraphy, and carpet weaving.

Men traditionally wear a long, loose robe with a hood (djellaba) and leather slippers (balgha). Women wear a long dress with embroidery (kaftan), balgha, and a headscarf (hijab).

Architecture

Traditional houses in Morocco have mud brick walls, flat roofs, and an inner courtyard with a fountain or pool.

Cuisine

The Moroccan diet is based on meat, rice, and vegetables. Typical dishes include couscous (steamed granules of semolina with meat and vegetables), harira (a soup of lentils, meat, noodles, and onions), jawhara (a pastry with milky cream between the sheets), rfissa (a dish of spiced chicken and lentils), and zaalouk (a salad of cooked eggplants and tomatoes).

Holidays and festivals

Like other Muslim countries, Morocco celebrates Islamic New Year, Mawlid, Eid al-Fitr, and Eid al-Adha. It also commemorates New Year’s Day and Labor Day.

Specific Moroccan holidays include Proclamation of Independence Day on January 11, Amazigh New Year on January 14, Throne Day on July 30, Oued Ed-Dahab Day on August 14, Revolution Day on August 20, Youth Day on August 21, Green March Day on November 6, and Independence Day on November 18.

Amazigh New Year

Other celebrations include the Kalaat Mgouna Rose Festival, the Imilchil Marriage Festival, which celebrates the legend of two lovers who drowned themselves after their parents forbade their marriage, and the Marrakesh Popular Arts Festivals, which features dance, fire swallowing, music, and snake charming.

Imilchil Marriage Festival

Landmarks

There are nine UNESCO World Heritage Sites: Archeological site of Volubilis, Ksar of Ait-Ben-Haddou, Historic City of Meknes, Medina of Essaouira, Medina of Fez, Medina of Marrakesh, Medina of Tétouan, Portuguese City of Mazagan, and Rabat, Modern Capital and Historic City: a Shared Heritage.

Archeological site of Volubilis

Other landmarks include the Bahia Palace, the Hassan II Mosque, the Khnifiss National Park, the Taforalt Cave, and the Talassemtane National Park.

Hassan II Mosque

Famous people

Badr Hari - kick boxer

French Montana - rapper

Gad Elmaleh - actor and comedian

Hicham El Guerrouj - athlete

Leila Abouzeid - writer

Mohammed Khair Eddine - writer

Rhizlane Siba - athlete

Shatha Hassoun - singer

Soumaya Akaaboune - actress

Yasmine Kabbaj - tennis player

Yasmine Kabbaj

You can find out more about life in Morocco in this post and this video.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

29 January 1850 saw the birth in Muthill of Helen Gloag, who through a series of remarkable events went on to become the Empress of Morocco. you have not heard of Helen Gloag, a Scottish woman who became Sultana of Morocco, you are not alone. Her story recently resurfaced. Helen, a traditional Scottish redhead, was the eldest of Andrew and Anna’s four children. Tragically, Anna lost her mother when she was a child, and her father remarried. Her relationship with her new stepmother was said not to be very good, and as a result, Helen left home when she was just 19-years-old in May 1769 to travel as an indentured servant to the New World – the British colony of South Carolina to be specific. Helen, who was travelling with some female friends, would not make it to the New World. After sailing for just two weeks, her ship was attacked off the coast of Spain by the Barbary pirates from Morocco. Along with the other women, Helen was taken to a slave market in Algiers in what is today Algeria. The men on the ship were all murdered. The beautiful green-eyed Scottish woman was sold to a wealthy Moroccan who then handed her over to Sultan Sidi Mohammid ibn Abdullah of Morocco (a member of the Alaouite/Alawi Dynasty that still rules Morocco to this day) as a gift. Due to her beauty, the Sultan added her to his harem. Before long, she became his fourth wife and would go on to be the principal wife who was given the title of Sultana of Morocco. She was called Lalla Zahra; ‘Lalla’ is a term used in Morocco, ahead of the person’s given name, to show respect and is often used by noble and royal women. Reportedly, the Sultana was instrumental in convincing the Sultan to have seafarers and slaves, who had been captured by pirates, released. As a favourite of his, she was able to write and send gifts back home to Scotland; the Sultan, who was the first head of state to recognise the United States, even allowed her brother, Robert, to visit her in Morocco on occasion. Robert was responsible for her story being brought back to her homeland. Sultan Sidi Mohammid died in 1790, and one of his sons, by a German woman in his harem, Yazid took the throne to become Sultan of Morocco. Not wanting to have any competition for the throne, he ordered the killing of his two brothers, who he is said to have been incredibly envious of, by Helen – even though she had attempted to keep them safe by sending them away to a monastery in Tétouan (a town where his first order of business was to persecute the Jews). She reportedly sent out a plea to the British Navy for assistance, but they would not make it to her sons before the new Sultan’s troops would discover and murder both boys. What exactly happened to the Scottish Sultana of Morocco has never been clear, as nothing was heard from or about her after the death of her sons; however, it has been assumed that she was killed by Yazid or his forces in the two years – known to be full of unrest – after he took the throne. As I said at the start interest in Helen Gloag only recently peaked thanks to a historical novel based upon her, The Fourth Queen by Debbie Taylor https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/343128.The_Fourth_Queen

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hafez al-Assad Biography and Profile

New Post has been published on https://www.politicoscope.com/hafez-al-assad-biography-and-profile/

Hafez al-Assad Biography and Profile

Born in the village of Qardaha in Syria on October 6, 1930, Hafez al-Assad became Syrian president of the country in 1971, after taking part in multiple coups. Though widely criticized for brutal tactics (most notably the 1982 Hama massacre), he is also praised for bringing stability to Syria, and for improving relations between Syria and Western powers by supporting America in the Persian Gulf War. He served as president of Syria until his death on June 10, 2000.

Of the five members of the Ba’ath Party’s Military Committee who seized power in Syria in 1963, Hafez Al-Assad went the furthest. Of the other four, one took the blame for Syria’s loss of the Golan Heights during the Six Day War and was pushed out of politics; one committed suicide; a third was assassinated; the other died in prison after 25 years.

Assad was born into a modest family in Qurhada in Syria’s north-western mountains, a village which was said to be 10 kilometres from the nearest road. He went to school in Latakia at a time when less than a quarter of Syrian children received an education. According to Patrick Seale’s unofficial biography, Asad of Syria: The Struggle for the Middle East, he inherited his father’s love of books, poetry and Arabic language.

Much has been made of the Assad family’s Alawi background and what it means to have members of a minority Shia Muslim sect rule over a predominantly Sunni Muslim country. Assad senior did not surround himself entirely by other Alawites, though; amongst those associates whom he kept close was a Palestinian Christian speechwriter and a Palestinian soldier who was his bodyguard. His foreign minister, chief aide and first three prime ministers were Sunni Muslims. Ultimately, the military was where a number of Assad’s loyal contacts and alliances lay. After joining the military academy in Homs, Assad joined the flying school at Aleppo, graduating into the air force in his early twenties.

In the period between France’s exit of the country in 1946 and Hafez Al-Assad becoming president a number of coups rocked Syria. Hence, Assad’s arrival on the scene (what he labelled the “corrective movement”) and his ability to hold power for the next thirty years is regarded by most observers as characteristic of one of his strengths – stability. He also set about portraying himself as a man of the people by visiting remote provinces of the country and talking to the people who lived there. According to Seale, he would bring back “sackfuls” of complaints for his staff to deal with.

Perhaps one of the most defining moments, or losses, in Hafez Al-Assad’s life was the Six Day War with Israel in which Syria lost the Golan Heights. He believed that this defeat could be overturned and Syria’s position vis-a-vis Israel became the vanguard of his presidency. His image as an Arab leader willing to confront Israel was confirmed on 6 October 1973 when his forces attacked the occupying Israeli forces in the Golan Heights; at the same time, taking such a stand isolated him. His co-belligerents Egypt and Jordan went on to sign separate peace treaties with Israel.

To face Israel Assad needed friends and so he moved Syria closer to the Soviet Union. As Patrick Seale recognises, though, “he grasped early on that the Soviet Union’s friendship for the Arabs would never match the United States’ generous, sentimental and open-handed commitment to Israel.” Israel’s presence was particularly unsettling for a region that had been under the control of both the Europeans and the Ottoman Empire within living memory.

Assad was known to be an ardent supporter of the Palestinian cause, but his involvement in the Lebanese civil war tarnished this reputation immensely. The “red-line” agreement saw the White House issue support for Syria to take a constructive role in the civil war; the chief architect of the agreement, then Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, felt that if Assad could be tempted to crush the Palestinians in order to prevent an Israeli attack on Lebanon it would discredit the Syrian leader and curb Soviet power.

It worked. Assad sent in troops, sieges were broken and Palestinians were massacred. Whilst Assad’s relationship with the Palestinians and the Soviet Union took a severe blow, Israel’s relations with Lebanese Christians were strengthened.

Following Assad’s intervention in Lebanon in 1976 there was a series of explosions and assassinations in Syria, many of which were attributed to the Muslim Brotherhood. On 16 June 1979, Alawite officer cadets were assembled in the dining hall of the Aleppo Artillery School when gunmen opened fire on them, killing up to 83. Assassins targeted members of the government and prominent Alawites.

Internally, Assad’s biggest threat came from the Brotherhood. In retaliation for an assassination attempt on Assad in 1980 his brother Rifaat led the Defence Brigades in committing the Tadmor Prison massacre; 1,000 prisoners were killed. The notorious prison was known for holding many members and supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood. The crackdown on the group reached its apogee in 1982 in Hama. Regime soldiers rolled into the city and spent three weeks massacring the residents before the air force was sent in to finish off the job. Tens of thousands were killed, mosques were flattened and whole neighbourhoods were destroyed.

The ability to crush opposition to his rule was a prominent theme throughout Assad’s presidency. He had succeeded in eliminating other members of the Military Committee, tried to wipe out the Brotherhood and would later banish his brother Rifaat when he suspected that he was moving closer to his own position as president. Yet, despite his opposition to Israel and the west also being a presidential norm for Hafez Al-Assad, Syrian troops were sent to fight in the 1990 Gulf War on the American side. It is claimed that he went on to conduct peace talks with Israel, which stalled thanks to Tel Aviv’s refusal to give back the Golan Heights.

During his 30 years in power Assad cut basic food prices in Syria and built schools, hospitals, roads, damns and railways. The economy grew with foreign aid reaching £600 million from a starting point of £50 million. At the same time, he established an authoritarian state, curtailed freedom of speech and secured his tenure with 99 per cent “yes” referendums. He was Chief Judge, gave himself the power to dissolve parliament and permitted civilians to be tried in military courts and tortured in secret prisons.

Hafez Al-Assad died on 10 June 2000. His eldest son Basil was a lieutenant colonel in the military and was being groomed to take over as president when he was killed in a car crash on 21 January 1994. Basil’s brother, Bashar, was recalled from London where he was training as an ophthalmologist and pushed through the military in preparation to take over as head of the Assad dynasty; Bashar remains at the helm in Damascus to this day.

Hafez al-Assad Biography and Profile (Biography / Middle East Monitor / Politicoscope)

#Ba'ath Party#Ba'ath Party Congress#Bashar al-Assad#Biography and Profile#Hafez al-Assad#Hafez al-Assad Biography and Profile#Syria

0 notes

Text

Hafez al-Assad Biography and Profile

New Post has been published on https://www.politicoscope.com/hafez-al-assad-biography-and-profile/

Hafez al-Assad Biography and Profile

Born in the village of Qardaha in Syria on October 6, 1930, Hafez al-Assad became Syrian president of the country in 1971, after taking part in multiple coups. Though widely criticized for brutal tactics (most notably the 1982 Hama massacre), he is also praised for bringing stability to Syria, and for improving relations between Syria and Western powers by supporting America in the Persian Gulf War. He served as president of Syria until his death on June 10, 2000.

Of the five members of the Ba’ath Party’s Military Committee who seized power in Syria in 1963, Hafez Al-Assad went the furthest. Of the other four, one took the blame for Syria’s loss of the Golan Heights during the Six Day War and was pushed out of politics; one committed suicide; a third was assassinated; the other died in prison after 25 years.

Assad was born into a modest family in Qurhada in Syria’s north-western mountains, a village which was said to be 10 kilometres from the nearest road. He went to school in Latakia at a time when less than a quarter of Syrian children received an education. According to Patrick Seale’s unofficial biography, Asad of Syria: The Struggle for the Middle East, he inherited his father’s love of books, poetry and Arabic language.

Much has been made of the Assad family’s Alawi background and what it means to have members of a minority Shia Muslim sect rule over a predominantly Sunni Muslim country. Assad senior did not surround himself entirely by other Alawites, though; amongst those associates whom he kept close was a Palestinian Christian speechwriter and a Palestinian soldier who was his bodyguard. His foreign minister, chief aide and first three prime ministers were Sunni Muslims. Ultimately, the military was where a number of Assad’s loyal contacts and alliances lay. After joining the military academy in Homs, Assad joined the flying school at Aleppo, graduating into the air force in his early twenties.

In the period between France’s exit of the country in 1946 and Hafez Al-Assad becoming president a number of coups rocked Syria. Hence, Assad’s arrival on the scene (what he labelled the “corrective movement”) and his ability to hold power for the next thirty years is regarded by most observers as characteristic of one of his strengths – stability. He also set about portraying himself as a man of the people by visiting remote provinces of the country and talking to the people who lived there. According to Seale, he would bring back “sackfuls” of complaints for his staff to deal with.

Perhaps one of the most defining moments, or losses, in Hafez Al-Assad’s life was the Six Day War with Israel in which Syria lost the Golan Heights. He believed that this defeat could be overturned and Syria’s position vis-a-vis Israel became the vanguard of his presidency. His image as an Arab leader willing to confront Israel was confirmed on 6 October 1973 when his forces attacked the occupying Israeli forces in the Golan Heights; at the same time, taking such a stand isolated him. His co-belligerents Egypt and Jordan went on to sign separate peace treaties with Israel.

To face Israel Assad needed friends and so he moved Syria closer to the Soviet Union. As Patrick Seale recognises, though, “he grasped early on that the Soviet Union’s friendship for the Arabs would never match the United States’ generous, sentimental and open-handed commitment to Israel.” Israel’s presence was particularly unsettling for a region that had been under the control of both the Europeans and the Ottoman Empire within living memory.

Assad was known to be an ardent supporter of the Palestinian cause, but his involvement in the Lebanese civil war tarnished this reputation immensely. The “red-line” agreement saw the White House issue support for Syria to take a constructive role in the civil war; the chief architect of the agreement, then Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, felt that if Assad could be tempted to crush the Palestinians in order to prevent an Israeli attack on Lebanon it would discredit the Syrian leader and curb Soviet power.

It worked. Assad sent in troops, sieges were broken and Palestinians were massacred. Whilst Assad’s relationship with the Palestinians and the Soviet Union took a severe blow, Israel’s relations with Lebanese Christians were strengthened.

Following Assad’s intervention in Lebanon in 1976 there was a series of explosions and assassinations in Syria, many of which were attributed to the Muslim Brotherhood. On 16 June 1979, Alawite officer cadets were assembled in the dining hall of the Aleppo Artillery School when gunmen opened fire on them, killing up to 83. Assassins targeted members of the government and prominent Alawites.

Internally, Assad’s biggest threat came from the Brotherhood. In retaliation for an assassination attempt on Assad in 1980 his brother Rifaat led the Defence Brigades in committing the Tadmor Prison massacre; 1,000 prisoners were killed. The notorious prison was known for holding many members and supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood. The crackdown on the group reached its apogee in 1982 in Hama. Regime soldiers rolled into the city and spent three weeks massacring the residents before the air force was sent in to finish off the job. Tens of thousands were killed, mosques were flattened and whole neighbourhoods were destroyed.

The ability to crush opposition to his rule was a prominent theme throughout Assad’s presidency. He had succeeded in eliminating other members of the Military Committee, tried to wipe out the Brotherhood and would later banish his brother Rifaat when he suspected that he was moving closer to his own position as president. Yet, despite his opposition to Israel and the west also being a presidential norm for Hafez Al-Assad, Syrian troops were sent to fight in the 1990 Gulf War on the American side. It is claimed that he went on to conduct peace talks with Israel, which stalled thanks to Tel Aviv’s refusal to give back the Golan Heights.

During his 30 years in power Assad cut basic food prices in Syria and built schools, hospitals, roads, damns and railways. The economy grew with foreign aid reaching £600 million from a starting point of £50 million. At the same time, he established an authoritarian state, curtailed freedom of speech and secured his tenure with 99 per cent “yes” referendums. He was Chief Judge, gave himself the power to dissolve parliament and permitted civilians to be tried in military courts and tortured in secret prisons.

Hafez Al-Assad died on 10 June 2000. His eldest son Basil was a lieutenant colonel in the military and was being groomed to take over as president when he was killed in a car crash on 21 January 1994. Basil’s brother, Bashar, was recalled from London where he was training as an ophthalmologist and pushed through the military in preparation to take over as head of the Assad dynasty; Bashar remains at the helm in Damascus to this day.

Hafez al-Assad Biography and Profile (Biography / Middle East Monitor / Politicoscope)

#Ba'ath Party#Ba'ath Party Congress#Bashar al-Assad#Biography and Profile#Hafez al-Assad#Hafez al-Assad Biography and Profile#Syria

0 notes

Text

Hafez al-Assad Biography and Profile

New Post has been published on https://www.politicoscope.com/hafez-al-assad-biography-and-profile/

Hafez al-Assad Biography and Profile

Born in the village of Qardaha in Syria on October 6, 1930, Hafez al-Assad became Syrian president of the country in 1971, after taking part in multiple coups. Though widely criticized for brutal tactics (most notably the 1982 Hama massacre), he is also praised for bringing stability to Syria, and for improving relations between Syria and Western powers by supporting America in the Persian Gulf War. He served as president of Syria until his death on June 10, 2000.

Of the five members of the Ba’ath Party’s Military Committee who seized power in Syria in 1963, Hafez Al-Assad went the furthest. Of the other four, one took the blame for Syria’s loss of the Golan Heights during the Six Day War and was pushed out of politics; one committed suicide; a third was assassinated; the other died in prison after 25 years.

Assad was born into a modest family in Qurhada in Syria’s north-western mountains, a village which was said to be 10 kilometres from the nearest road. He went to school in Latakia at a time when less than a quarter of Syrian children received an education. According to Patrick Seale’s unofficial biography, Asad of Syria: The Struggle for the Middle East, he inherited his father’s love of books, poetry and Arabic language.

Much has been made of the Assad family’s Alawi background and what it means to have members of a minority Shia Muslim sect rule over a predominantly Sunni Muslim country. Assad senior did not surround himself entirely by other Alawites, though; amongst those associates whom he kept close was a Palestinian Christian speechwriter and a Palestinian soldier who was his bodyguard. His foreign minister, chief aide and first three prime ministers were Sunni Muslims. Ultimately, the military was where a number of Assad’s loyal contacts and alliances lay. After joining the military academy in Homs, Assad joined the flying school at Aleppo, graduating into the air force in his early twenties.

In the period between France’s exit of the country in 1946 and Hafez Al-Assad becoming president a number of coups rocked Syria. Hence, Assad’s arrival on the scene (what he labelled the “corrective movement”) and his ability to hold power for the next thirty years is regarded by most observers as characteristic of one of his strengths – stability. He also set about portraying himself as a man of the people by visiting remote provinces of the country and talking to the people who lived there. According to Seale, he would bring back “sackfuls” of complaints for his staff to deal with.

Perhaps one of the most defining moments, or losses, in Hafez Al-Assad’s life was the Six Day War with Israel in which Syria lost the Golan Heights. He believed that this defeat could be overturned and Syria’s position vis-a-vis Israel became the vanguard of his presidency. His image as an Arab leader willing to confront Israel was confirmed on 6 October 1973 when his forces attacked the occupying Israeli forces in the Golan Heights; at the same time, taking such a stand isolated him. His co-belligerents Egypt and Jordan went on to sign separate peace treaties with Israel.

To face Israel Assad needed friends and so he moved Syria closer to the Soviet Union. As Patrick Seale recognises, though, “he grasped early on that the Soviet Union’s friendship for the Arabs would never match the United States’ generous, sentimental and open-handed commitment to Israel.” Israel’s presence was particularly unsettling for a region that had been under the control of both the Europeans and the Ottoman Empire within living memory.

Assad was known to be an ardent supporter of the Palestinian cause, but his involvement in the Lebanese civil war tarnished this reputation immensely. The “red-line” agreement saw the White House issue support for Syria to take a constructive role in the civil war; the chief architect of the agreement, then Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, felt that if Assad could be tempted to crush the Palestinians in order to prevent an Israeli attack on Lebanon it would discredit the Syrian leader and curb Soviet power.

It worked. Assad sent in troops, sieges were broken and Palestinians were massacred. Whilst Assad’s relationship with the Palestinians and the Soviet Union took a severe blow, Israel’s relations with Lebanese Christians were strengthened.

Following Assad’s intervention in Lebanon in 1976 there was a series of explosions and assassinations in Syria, many of which were attributed to the Muslim Brotherhood. On 16 June 1979, Alawite officer cadets were assembled in the dining hall of the Aleppo Artillery School when gunmen opened fire on them, killing up to 83. Assassins targeted members of the government and prominent Alawites.

Internally, Assad’s biggest threat came from the Brotherhood. In retaliation for an assassination attempt on Assad in 1980 his brother Rifaat led the Defence Brigades in committing the Tadmor Prison massacre; 1,000 prisoners were killed. The notorious prison was known for holding many members and supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood. The crackdown on the group reached its apogee in 1982 in Hama. Regime soldiers rolled into the city and spent three weeks massacring the residents before the air force was sent in to finish off the job. Tens of thousands were killed, mosques were flattened and whole neighbourhoods were destroyed.

The ability to crush opposition to his rule was a prominent theme throughout Assad’s presidency. He had succeeded in eliminating other members of the Military Committee, tried to wipe out the Brotherhood and would later banish his brother Rifaat when he suspected that he was moving closer to his own position as president. Yet, despite his opposition to Israel and the west also being a presidential norm for Hafez Al-Assad, Syrian troops were sent to fight in the 1990 Gulf War on the American side. It is claimed that he went on to conduct peace talks with Israel, which stalled thanks to Tel Aviv’s refusal to give back the Golan Heights.

During his 30 years in power Assad cut basic food prices in Syria and built schools, hospitals, roads, damns and railways. The economy grew with foreign aid reaching £600 million from a starting point of £50 million. At the same time, he established an authoritarian state, curtailed freedom of speech and secured his tenure with 99 per cent “yes” referendums. He was Chief Judge, gave himself the power to dissolve parliament and permitted civilians to be tried in military courts and tortured in secret prisons.

Hafez Al-Assad died on 10 June 2000. His eldest son Basil was a lieutenant colonel in the military and was being groomed to take over as president when he was killed in a car crash on 21 January 1994. Basil’s brother, Bashar, was recalled from London where he was training as an ophthalmologist and pushed through the military in preparation to take over as head of the Assad dynasty; Bashar remains at the helm in Damascus to this day.

Hafez al-Assad Biography and Profile (Biography / Middle East Monitor / Politicoscope)

#Ba'ath Party#Ba'ath Party Congress#Bashar al-Assad#Biography and Profile#Hafez al-Assad#Hafez al-Assad Biography and Profile#Syria

0 notes

Photo

Golden Doors, Royal Palace, Fez, Morocco: The Royal Palace or Dar al-Makhzen is the palace of the King of Morocco in the city of Fez, Morocco. Its original foundation dates back to the foundation of Fes el-Jdid, the royal citadel of the Marinid dynasty, in 1276 CE. Most of the palace today dates from the 'Alawi era. Wikipedia

113 notes

·

View notes