#Ahagon Shoko

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Folks in mainland Japan: A super rare opportunity to see Ahagon Shoko's photographs of Okinawan farmers' resistance to US land thefts in the 1950s. The exhibition runs at the Maruki Gallery in Saitama 23 Feb ~ 6 May.

阿波根昌鴻(あはごんしょうこう、1901-2002)は沖縄戦後、米軍に占領された伊江島で農民たちと共に非暴力の土地闘争を行った人物として知られています。阿波根は「銃剣とブルドーザー」と呼ばれた強制的な土地接収や米軍の横暴、射爆演習場による被害を記録するためにカメラを入��して1955 年から島の記録を始めました。島で唯一のカメラを米軍に抵抗する手段とした阿波根は、「乞食行進」と呼ばれる行脚や陳情を展開するなかで沖縄における「島ぐるみ闘争」の一翼を担うようになりました。 生前、唯一の写真集として『人間の住んでいる島』(1982年)が出版されていますが、ここに収録された闘争の写真以外にも島の人々の肖像や日常を写した写真が数多く遺されていることが分かりました。 本土での初めての展覧会となる本展では、3000枚以上ものネガから新たに制作したデジタルプリント 約350点を展示します。「沖縄のガンジー」と呼ばれ、平和運動家として知られる阿波根の写真家としての側面をご覧ください。

主催:原爆の図 丸木美術館 共催:わびあいの里、島の宝・阿波根昌鴻写真展実行委員会 企画:小原真史 企画協力:阿波根昌鴻資料調査会、東京工芸大学、小原佐和子

#Photographer#Okinawa#Japan#Saitama#Ahagon Shoko#Shoko Agahon#Okinawan Farmers Resistance#United States#US Military

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

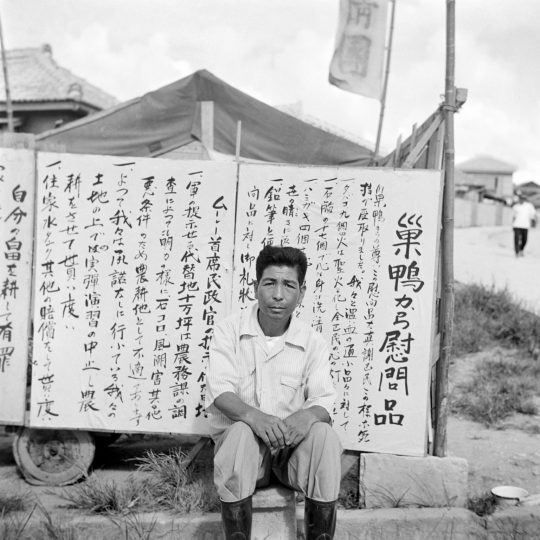

Shoko Ahagon

- Sue against U.S. servicemen who are Christians by holding up a cross, Iejima Okinawa.

1955

133 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Photos from the House of the Peace of Mind, a building next to an anti-base museum established by Ahagon Shoko in Iejima, Okinawa.

#photography#history#okinawan history#okinawa#anti-base movement#typography#japanese#peace movement#original photography

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://english.ryukyushimpo.jp/2021/06/08/33749/

Shoko Ahagon’s legacy of the Ie Land Struggle and Solidarity Dojo passed on to Ie Elementary School students

May 31, 2021 Ryukyu Shimpo

By Mitsue Chinen

On May 25, the 6th graders of Ie Elementary School learned about peace at the Danketsu Dojo (solidarity training center) in Maja, Ie Village, and in their classrooms at Ie Elementary School. The 30-hour learning opportunity raised awareness of the tragic Invasion of Ie Shima during WWII and elevated the children’s desire for peace. Director of Education Tsunenobu Uchima served as the lecturer and shared with the children the historical background of Danketsu Dojo.

Uchima explained, “Danketsu Dojo was founded in 1970 in Maja by the late Shoko Ahagon and others who fought in the Land Struggle in Ie Village under U.S. rule. The dojo served as a base for resistance against land confiscation and U.S. military exercises, and as a place to train successors in the struggle to take back land rights.” Using photos and panels, Uchima further explained, “The ‘Ie Island Land Protection Association’ advanced the fight by petitioning the U.S. government and organizing protests.”

Ryo Kurashita said, “It’s scary to think what would have happened to Ie Island if Shoko Ahagon hadn’t fought back.” Hinami Tanahara added, “If Mr. Ahagon hadn’t acted, I don’t think Ie Island would be here today, so I’m grateful.”

Makoto Hirata, a 6th-grade teacher, said, “There is a lack of knowledge of who started the war and why. [The children] study history in the 6th grade, so I hope to teach them the preciousness of peace.”

Uchima said, “Wars don’t start overnight. I want [the students to] read history books and newspapers, be curious, and learn about their world.” To conclude their learning, the students are scheduled to put on a play about peace and their local heroes.

(English translation by T&CT and Monica Shingaki)

#Ryukyu Shimpo#Mitsue Chinen#Monica Shingaki#Shoko Ahagon#Ahagon Shoko#Ie Island#Okinawa#Okinawan#United States#US Military#News#History

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Beginning of Resistance Against the Military Land Issues in Okinawa by Yoshimi Suda

During the Battle of Okinawa, in Iejima, 1500 civilians, 2000 Japanese soldiers, and 800 American soldiers were killed. It is often called “epitome of the battle of Okinawa” since the battle on the island was so fierce and people died from starving, firebombing, and compulsory group suicide in caves. Iejima is a place where many poignant memories have remained.

Shoko Ahagon, a leader of the resistance against the US military land use, lost his only son and his in law’s during the battle. The problem of US military land use can be traced back in 1947, when residents came back two years after the end of the war, and 63% of the land had already been confiscated by the US military. It became a serious issue in 1954, when the US ordered people at Maja to evacuate and leave their fields (which are a significant place for farmers), thus breaking the promise that the US military made with villagers that they could farm as much as they want (p.5). After that, land issues developed even more seriously and the US military began to take land with bulldozers against unarmed villagers. The “Petition Regulations” that have been made naturally through the movement encompassing the anti-base movement has been nonviolent.

Today, the US base issue still exists in Okinawa and with greater attention and urgency. New US base construction issues in Henoko have lasted for more than two decades since 1995, and they have yet to be solved. In addition to the Henoko issue, the bases have spurred problems ranging from Osprey flight training, environment contamination, to raping incidents by GIs. As time passes, an issue that has been considered an “Okinawan issue”, is now reconsidered and starting to be recognized in the framework of autonomy and discrimination that resides in Japan. I, as a student from Japan, personally feel that the US base issue has pointed out the ignorance and indifference of the mainlanders about Okinawa. The majority of people, including myself, have ignored what is ongoing in Okinawa, which occupies only 0.6% of Japanese territory, because it seems there is no connection between the issues and our daily lives.

Getting back to Ahagon, I think that the history of resistance in Iejima led by Ahagon will allow us to learn about the core of the resistance that continues today. What the original members of the resistance wanted was a democratic society. In addition, I think that the point of the anti-base movement is that it is deeply connected with mournful war-time experiences and memories, since it is well represented in most Okinawan literature. Without understanding this point, it is difficult to understand why Okinawan people protested so strongly against the US bases until now. Not only do the US bases affect their daily lives with noise, fear, and so on, but they also provokes memories of the history of the battle of Okinawa, when people were oppressed and “treated as dirt”. The more I know about the history of Iejima, the clearer the resistance against the US base issue becomes.

2 notes

·

View notes