#2018 Notable Social Studies Trade Books for Young People

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Link

The seemingly unassailable world of the male creative genius seems to be crumbling: Roman Polanski and Bill Cosby were recently expelled from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Junot Diaz stepped down as Pulitzer Prize chair after multiple women have spoken out about his pattern of harassment; and, 10 years after David Foster Wallace’s death, Mary Karr is reminding the world of his persistent abuse and stalking. In this unique social and political moment, a previously untouchable artistic archetype has finally become something close to vulnerable.

Genius is power. It is unquantifiable, uncontainable, and like beauty, exists in the eyes of the beholder. Genius enhances access—sexual, social, economic, political. It is a collective agreement—or, in many cases, a collective lie—that grants boundless latitude to those we anoint with the title.

But genius is also an indelibly gendered currency used by men—almost always men—of means and success to purchase license. The lie of genius is inextricable from the lie of meritocracy: Culture dictates that these men have risen to fame and success because of their unstoppable genius. But now that so many geniuses stand accused of abuses of power including sexual assault and violence; and as debates about separating the art from the artist spill into every corner of media and pop culture, the aesthetic alibi that artistic genius exists unfettered by lowly considerations like morality may no longer hold up under scrutiny.

With the rise of auteur theory in the mid–20th century, film joined the ranks of other fine arts, like painting and writing, that have long cultivated the mythology of the genius. Auteur theory, originating in French film criticism, credits the director with being the chief creative force behind a production—that is, the director is the “author.” Given that film, with its expansive casts and crews, is one of the most collaborative art forms ever to have existed, the myth of a singular genius seems exceptionally flawed to begin with. But beyond the history of directors like Terrence Malick, Woody Allen, and many more using their marketable auteur status as a “business model of reflexive adoration,” auteur worship both fosters and excuses a culture of toxic masculinity. The auteur’s time-honored method of “provoking” acting out of women through surprise, fear, and trickery—though male actors have never been immune, either— is inherently abusive. Quentin Tarantino, Lars Von Trier, Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick, and David O. Russell, among others, have been accused of different degrees of this, but the resulting suffering of their muses is imagined by a fawning fanbase as “creative differences,” rather than as misogyny and as uncompromising vision rather than violence. Allegations that Tarantino forced Uma Thurman, for instance, to disastrously perform her own driving stunt in Kill Bill: Volume 2—as she put it, part of a dehumanization “to the point of death”—is not dissimilar to Alfred Hitchcock’s torment of the actress Tippi Hedren, both dynamics masquerading as artist-muse relationships transcending common sense. As Imran Siddiquee writes of genius directors and abusive behavior: “Many of the ‘greatest’ artists in our most influential visual artform continue to be celebrated for their own obsessive, often abusive exercises of power and control.”

Daniel Day-Lewis’s temperamental dressmaker Reynolds Woodcock in 2017’s critically lauded Paul Thomas Anderson film Phantom Thread has all the makings of a genius: He is successful; he is considered a visionary by the elite; he is messy; he is twisted; and he preys on young women. Phantom Thread was a frontrunner in the Oscars race this year, along with Darkest Hour, a character study of of Winston Churchill at the dawn of Britain’s entry into World War II. Gary Oldman (alleged wife beater), won Best Actor for his role as Churchill; elsewhere at the Oscars, Kobe Bryant (charged with sexual assault in 2003) won for best animated short. Guillermo Del Toro took home the Best Director Oscar for The Shape of Water, which also won Best Picture—and while the film’s win is notable given that no film with a female protagonist has won the award in 14 years, Del Toro’s explicit supportof Roman Polanski (accused of sexual assault by five people; charged with drugging and raping a minor and then fleeing the United States to avoid sentencing) make his position as a supposedly progressive director a tenuous one at best. The Academy Awards have always been deeply entrenched in establishment capitalism and Hollywood liberal lip service, but amid the flurry of the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements, the 2018 awards offered an instructive example of what still holds primacy in the film industry: the sometimes difficult and troubled, often abusive, and always male genius.

Men like Polanski retain artistic cred and social license because gatekeepers and fans argue that their cultural contributions outweigh their individual transgressions and crimes. It is not that passive consumers of art don’t recognize that their idols may be flawed: It’s that genius is imagined as a separate faculty that exists beyond ethics and morality. Genius is unemotional and objective, elevated beyond such paltry concerns. Of course the generous leaps of imagination and apologism offered to men of genius do not apply to women and gender-nonconforming creators, so if the latter should distinguish themselves, it is not because they are genius, but it is because they are “different.”

Superlative women have always been encouraged to believe they are notable because of an inherent “difference” from other girls; this difference is what distinguishes them in creative fields dominated by white men. I once thought I had the “androgynous mind” Virginia Woolf says is necessary to creativity. Mary Wollstonecraft, in her groundbreaking 1792 treatise A Vindication Of The Rights Of Woman, wondered whether the “few extraordinary women” in history were indeed “male spirits, confined by mistake to female frames.” Even Ursula K. Le Guin, whose revolutionary fiction challenged contemporary humanity’s preoccupation with gender, said some strange stuff about her own conception of herself as a “generic he,” a “poor imitation,” and a “substitute man.”

While we know it is both reductive and essentialist to reason this way, it’s historically understandable. The cultural misogyny that underlies the archetype of the male genius has ancient roots. According to Christine Battersby’s 1989 book Gender and Genius: Towards a Feminist Aesthetics, the 19th-century reworked an “older rhetoric of sexual exclusion” from Renaissance ideas about sexual difference in the arts (which were themselves based on the ancient Greeks and Romans). But the Romantics contributed something unique to “anti-female traditions”: While emotionality and expression—traditionally “feminine” attributes—rose in prominence, women themselves were further downgraded as artistic inferiors. Notes Battersby: “The Romantic artist feels strongly and lives intensely: the authentic work of art captures the special character of his experience.” And his art became his individualistic expression.

Originality and creativity wasn’t always inherent to artistic practice. Greeks thought of art as mimetic; the poet as a prophet; painting and sculpture pretty facsimiles of the natural world. The Middle Ages similarly viewed the artist as ungod-like, simply an imitator rather than a creator. The term “masterpiece,” had less to do with terrific originality and more to do with the “piece of work produced by an apprentice who showed sufficient skill.” A master was a “trade-union leader”—and women were active in these guilds as well. “Hostility towards women in the arts only increased when the status of the artist began to be distinguished from that of the craftsman…suitable only for the most perfect (male) specimens of humanity,” writes Battersby. She dates this change to when artists began gaining patronage during the Renaissance, freeing artistic creation from religious restrictions. In other words, when a great deal of money entered into the equation, art became profitable and it suited men to push out competition.

The modern term “genius” comes from the melding of two words: “genius,” a symbol of fertility represented by a little boy, and “ingenuity,” or skill. While Renaissance women lacked genius, they were artistic inferiors because they lacked “ingenium”—according to Juan Huarte’s 1575 Examen de Ingenius, men, in the Aristotelian fashion, were hot and dry; women, cold and wet, were a “lesser man.” (Aristotle also thought women were “flower pots” and sterile—creativity and procreativity both being male attributes.) Huarte’s physiological reasoning, though widely discredited, was later referenced by Schopenhauer, whose argument that women “lack all higher mental faculties” is a good example of Romantic reworking of cultural misogyny. (It might be worth noting that Schopenhauer is a well-known touchstone of Woody Allen’s many autobiographically based neurotic male protagonists.)

Further, madness and deviance were idiosyncrasies worked into the masculine artistic template. Artists, once expected to uphold societal values, became “countercultural” around the time of Lord Byron, who was once described by an ex-lover as “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.” The image of the antihero, the messy, the eccentric, the intoxicated artist persisted from the Romantic period through today. And while craziness was celebrated in the elite men, “female madness” was stigmatized. As Vox writer Tara Isabella Burton notes, the male artistic establishment begets the tortured, unruly genius sex: “That female flesh is the reward for a male job well done is not an uncommon cultural phenomenon in any field, but in the arts, that dynamic often takes on a faux-spiritual aspect.”

Even as the #MeToo movement picks up momentum, famous men who have sustained public critique in the past few months are already plotting their comebacks, with ample assistance from industry media. Tarantino, a man accused of choking Thurman and Diane Kruger for the sake of on-camera authenticity; who told Rose McGowan he used to jerk off to her; and who publicly defended Polanski, has unveiled his latest enterprise: a movie about Charles Manson. Charlie Rose has reportedly floated a comeback via a talk show in which he would interview men like Louis C.K. brought down by#MeToo—thereby facilitating their own comebacks—and Matt Lauer apparently hopes to be back on television screens as well. Despite the recent spate of high-profile falls from grace, the culture of media and art world are arranged such that neither whisper nor lawsuit will be able to fell geniuses for long.

Those who try to separate the art from the artist are setting up an illogical argument: The art was alwaysseparated, which is why these male auteurs had the the license, the support, and the cover to victimize as they did and still make more celebrated art. In the aftershocks of predatory unveilings, we have seen multitudes mourn the loss of the genius of these men. We need to now consider that we have elevated what we’ve inscribed as genius at the expense of the humanity and potential of people they silenced, erased, and preyed upon. We need to examine the destruction wrought by the archetype, and acknowledge that we have let it fuel rape culture and sexual exploitation. We need to acknowledge that genius has been a construct all along—that it may not actually exist.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Author Interview with June Jo Lee & Man One

“Remix” is integral in Chef Roy Choi’s work as he uses food to remix culture and communities. What does remix mean to you and does it apply to your daily work?

JJL: As a food ethnographer, I think about “remix” all the time! Remix is now the culinary code for good and interesting food, not just in America but in the world. Remix represents a growing circle of empathy in which traditional walls between “us v. them” are cracking up and breaking down. We naturally express our remix identities and experiences by cooking and sharing foods we know and can imagine. As an immigrant, I am a “remix” of Seoul, Pusan, “Korea,” Texas, California, and “America.” As a student of cultural anthropology, remix represents the concept of bricoleur which (I immediately fell in love with) means someone who takes whatever is on hand to mix-and-match and create their own identity, meaning and truths. This is me. When Chef Roy Choi put Korean BBQ in a tortilla with Awesome sauce on a food truck and announced it on Twitter to the world, he was speaking to me.

M1: As an old school hip-hop head, REMIX to me means the fresh mixing of music or visual flavor and by flavor I mean style! I have created many murals and pieces of art where I have taken something cultural or iconic from my Mexican culture and “remixed” it to make it relevant to a new generation. It’s a lot of fun to do but also a great way to pass on legacy to future generations of young people.

June Jo Lee is an immigrant from South Korea and Man One is a child of immigrants (from Mexico.) How does your family immigrant experience influence your work?

JJL: An immigrant’s experience for me was source of my deepest suffering and greatest gift. I was awfully teased for my stinky food, my slanted eyes and my flat face in elementary school in Palo Alto, California. And, when I returned back to Seoul, South Korea as a third-grader, I was teased for my American accent, weird behaviors and not being a perfect Korean girl. I felt as though I didn’t fit in any which way, and so I escaped into books and the forest behind my house. I was very lonely and all alone. As I grew older, this “not fitting in” gave me the skills of adaptability, fluidity and empathy. I learned to see, hear and feel more deeply as a survival tool. And, I discovered cultural anthropology as a way of understanding me and my context in relation to others and their context. Anthropology led me to my profession as a researcher of food culture and a writer of food culture for kids. The books I write — I’m working on my next children’s book with Jacquline Briggs Martin — are based on deep ethnography of our foodways and diversity of ways of being in this world that I first experienced as an immigrant.

M1: Being a first generation US citizen, I have a great sense of American pride as well as cultural pride with my Mexican roots. Although I was born here, my first language was Spanish. I grew up watching Mexican TV shows and sports, like Lucha Libre (Mexican wrestling), these things were very influential and I draw inspiration from them all the time. I also grew up watching American TV and movies which were also very influential to me. Coming from an immigrant family I feel 100% connected to two different cultures at the same time. It’s a very unique experience and I love celebrating it in my art!

How does food play a role in your family traditions?

JJL: I love cooking for my family. After a long day of researching, writing and emailing, I cook…with a glass of White Burgundy…and seasonal vegetables and some good meats. I cook from memory of all the dishes I have eaten and imagination of new possibilities of remixing flavors, textures and experiences. Sometimes I listen to an audiobook (right now I’m listening to The Sun is Also a Star). And I enjoy being in my senses, my heart, my thoughts, my feelings. I have cooked dinner for my family ever since my kids were born, so we all share this time in the evening, all back at home, sitting around the table, sharing food I have made. Sometimes we talk. Sometimes my husband cooks. Now that my kids are in college, we still share this time when we are together. Sitting down and eating family dinner together is expected, the norm in our family tradition.

M1: "Food equals family,” it’s that simple. Most of my fondest memories of my grandparents were sitting around the kitchen table and helping in preparing large meals for the holidays. The smell of beans cooking or chili’s being roasted on the stove top are forever engrained in my head. Mexican hot chocolate (champurrado) and tamales were reserved for Christmas time. Capirotada (Mexican bread pudding) and torrejas de camaron (shrimp patties) were only served on Fridays during the Lent season. I can go on for days about the food and our traditions!

As a Korean American author and Mexican American artist, what reaction do you get from children when you share your personal experience? What are the biggest surprises?

JJL: Kids today either have already tried kimchi (my “stinky food”) and love it, or they pinch their noses after I open a jar during my author visits. But, by the end of my book reading, they are all gathering around that funky jar, smelling and looking at the bubbles from the lacto-fermentation. My favorite quote is from a kindergartner in LA who asked, “why did you open that? It hurts me,” as I opened the jar. Afterwards she rushed up to have a closer look (and smell?). Another kindergartner boy who was Korean American asked me, “can you tie my shoe?” as his way to connect with me. All the kids that day then got to eat lunch from Chef Roy’s Kogi Food Truck. That was a perfect day!

M1: Kids love the book! They identify with the story so much and they love the graffiti style I brought to it, which makes me really proud. I knew many kids would really love it in LA, but I had no idea how deeply it would resonate with kids in so many other cities around the country! One of the biggest surprises is that many readers that I’ve met at book signings often think I’m the illustrator AND the chef! It must be the goatee I guess.

CHEF ROY CHOI marks the picture book debut for both of you (The book was co-written by Jacqueline Briggs Martin as part of her “Food Heroes” series.) What have you discovered working with teachers, librarians, and children?

JJL: I love teachers, librarians and children. They are the most open, curious, generous and weird cohorts I have ever worked with. (As a former Austinite, “weird” is a good thing in my book). In my day job as a food ethnographer, I usually work with corporate types in casual Thursday attire. I like them too. But I love teachers, librarians and children because they are our future.

M1: This book has opened up a whole new dimension to my career and put me in front of so many great people that I would’ve never met had it not been for this book. I’ve always enjoyed working with kids but I have a new found admiration for teachers and librarians. The work that these people do is so amazing and to know that my artwork is helping them facilitate the education of our next generation is just beyond words. I hope to create more books and stories that speak to all our kids, it’s such an amazing feeling to connect in this way.

Did you know? Chef Roy Choi and the Street Food Remix has received the following Awards & Honors: • Sibert Award Honor for Most Distinguished Informational Book 2018 • Notable Children’s Book 2018, American Library Association • Notable Social Studies Trade Book for Young People 2018, NCSS • Orbis Pictus Award Honor Book for Outstanding Nonfiction 2018, NCTE • “Outstanding Merit,” 2018 Best Children's Book of the Year, Bank Street College of Education • Texas Bluebonnet Award Master List 2018-2019 • Rhode Island Children’s Book Award Finalist 2019 • Vermont Red Clover Award Finalist 2019 • Finalist, INDIES Book of the Year 2017, Foreword Reviews • Junior Library Guild Selection

June Jo Lee is a good ethnographer, studying how America eats. She’s a national speaker on food trends and consults with organizations, from college campus dining to Google Food. She is also co-founder of publisher READERS to EATERS, with a mission to promote food literacy. Like Roy Choi, she was born in Seoul, South Korea, and moved to the United States where she grew up eating her mom’s kimchi. She now lives in San Francisco. Chef Roy Choi and the Street Food Remix is her first book. More about her at foodethnographer.com.

Man One has been a pioneer in the graffiti art movement in Los Angeles since the 1980s. His artwork has been exhibited in galleries and museums around the world, including Parco Museum in Japan and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. He has painted live onstage at music concerts and festivals. He is also co-founder of Crewest Studio, a creative communications company focusing on contemporary global culture. A lifelong Los Angeleno, he loved eating his family’s delicious Mexican recipes growing up. Chef Roy Choi and the Street Food Remix is his first children’s book. More about Man One at manone.com.

#READERS to EATERS#Chef Roy Choi#Picture Book#Nonfiction#Author Q & A#Author Q and A#cbcdiversity#diverse childrens books#diverse kidlit#own voices#remix#June Jo Lee#Man One#Jacqueline Briggs Martin

1 note

·

View note

Text

Week 8

Earlier this week, one of my favorite topics of discussion came up and was very casually debated among ourselves during our weekly seminar: the issues associated with cetacean captivity.

We’ve all heard the Blackfish arguments, and the advocacy for retiring and/or releasing captive marine mammals back into the wild. While there certainly is discrepancy among scientists and between marine park curators, biologists, and the general public on the ethics, complications, and realities of rehabilitating captive cetaceans, let me preface everything I’m about to say with the following:

Whether or not captivity is stressful or inherently damaging to the physiological and psychological health of marine mammals is not up for debate. There is simply too much evidence that supports the claim that captivity results in maladaptive and otherwise abnormal behavior, including self mutilation, stereotypic behavior, hyperagression, and increases the chances of reproductive complications, rejection of offspring, disease exposure/contraction, harm from element exposure, and increases heightens mortality rates in most species of marine mammals commonly maintained in captivity, notably orcas, bottlenose dolphins, belugas, pilot whales, pacific white-sided dolphins, and false killer whales (DeMaster & Drevenak, 1988 ; Perrin et al., 2009 ; Jett & Ventre 2011).

In the wake of documentaries like Blackfish, what now becomes of captivity? Has it truly lost all its value? Is there anything we can benefit from or learn by attempting to maintain these complex and demanding animals in captivity, all commercial purposes aside?

The answer: maybe.

We’ve all been there, and by “there” I mean Sea World, or Vancouver Aquarium, or Georgia Aquarium, or Marineland... you get the point.

I’ll be honest with you, my first encounter with a killer whale was in a captive environment when I was very young and impressionable and obviously ignorant to the complexities of ethics surrounding captivity. As I aged, I learned about the commercial whale and dolphin trade, and the problems that come with for-profit marine parks (*cough*) as well as the facilities that affiliate with them. It becomes an incredibly muddy and sensitive grey area to tread when one, especially a biologist, goes about listing the nuances and pros/cons to maintaining marine mammals in captivity.

As I maintained earlier, my personal opinions do not necessarily reflect those of Cascadia Research Collective, so please bear this in mind as I go about offering my two cents here. Here we go...

Pros

Public attention / Exposure; Such as in my case, aquarium facilities can provide a wonderful foundation for the general public to see whales and dolphins up close and personal and, supposedly, develop an appreciation for them and foster a culture of love for the environment. Granted this is my own bias, I became acquainted with the orca and marine life at an aquarium. Later on down the line I also learned how that orca came to arrive at that aquarium (maybe some of you are familiar with Bjossa, a killer whale caught from Iceland in 1980?) and consequently shifted my interest in working with captive marine mammals to studying those in the wild. Today, I would never advocate for the deliberate capture of marine mammals for commercial purposes, ever, but when it comes to facilities that maintain rescued marine mammals, some animals cannot be successfully released to the wild given their circumstances and complicated social hierarchies. These individuals may remain in permanent captivity where they are used as ambassadors for their species and educational tools** to promote the conservation of wild animals and their natural environments. Personally, I would now prefer that people learn through documentaries and books, and maybe that’s unfair of me, but knowing what captivity does to these animals, I can’t bring myself to recommend it. **Personal opinions may vary on the ethics of doing this, and some may argue that nature should be allowed to take its course, as deaths in the wild are natural and normal and direct human intervention is unusual. It is common for captive cetaceans to experience chronic illness and be given constant veterinary attention in unsuitable artificial confines, and that begs the question of “what kind of life is that?”, but good God, is that another can of worms.

Research opportunities; In addition to developing improved husbandry techniques, which could lead to better veterinary care and general maintenance of marine mammals in captivity for the purpose of rescue and rehabilitation, there are still some research opportunities to be had in a captive environment. Some areas of study include examining the use of sonar echolocation in marine mammals, the results of which are intended to better our understanding of sound dynamics and perchance find ways to reduce the chances of entanglement in fishing nets and strikes by vessels.

Rehabilitation and Release; short-term captivity for preparation for rehabilitation and eventual release is something I wish more aquarium facilities could refine and focus on. As it is, maintaining marine mammals in captivity is logistically and financially difficult to nearly impossible, depending on the species, but some respond better to captivity than others. Consider seals and sea lions for example at the Marine Mammal Center in California and at Vancouver Aquarium in British Columbia. Cetaceans can be more difficult to rehabilitate, again, due to the complexities in their biology and behavior and susceptibility to stress (Zagzebski et al., 2006 ; Simon et al., 2009), although it has been done! Springer (A73), a killer whale from the Northern Resident Community in British Columbia was found emaciated and orphaned in Washington back in 2002. She was taken into a seaside pen and released back to her family unit after a breif period of time in human care. She now has two calves of her own and is alive and well. Several successful releases of smaller oceanic dolphins after maintenance in short-term and long-term captivity have occurred as well (Gales & Waples, 1993 ; Balcomb, 1995 ; Wells et al., 1998 ; UNIST, 2018), but follow-up has been inconsistent in many cases.

Captive breeding; No, I don’t mean for the commercial trade. I mean captive breeding for the purpose of wild repopulation. Now, let me be the first to say that I don’t think this is the best concept to experiment with, especially with endangered cetaceans where it would be most logical for this type of intervention to take place. Take the recent last-ditch efforts to save the Vaquita porpoise. Acute stress as a result of capture was believed to be the cause of death of one of the last remaining critically-endangered Vaquita porpoises when it was captured for the purpose of captive breeding (Pennisi, 2017). The resulting offspring as well as its parents would have later been released back into the wild in hopes of boosting their numbers. Because of stress associated with the capture of marine mammals, this is a practice that has barely been attempted, and maybe is best left a concept, although its a nice thought and often a better conservation effort when it comes to terrestrial or more adaptable animals.

Cons

Chronic/Sustained Stress; as a result of capture and confinement to small spaces, as well as unnatural social groupings, cetaceans may experience heightened stress levels over the long-term from having certain instincts and natural behaviors repressed. As we know, stress can have a severe negative impact on the bodies of organisms, and cetaceans are no different. This can increase their susceptibility to disease and increase the likelihood of experiencing reproductive complications such as miscarriages, stillbirths, and calf rejection. (Perrin et al., 2009; Rose et al., 2009; Jett & Ventre, 2011)

Maladaptive/abnormal behavior and repression of natural behavior; cetaceans often exhibit abnormal behavior in captivity, including stereotypic behavior like floating motionlessly, resting for unnaturally long periods, circle-swimming, chewing on foreign objects, hyperaggression towards their handlers and tankmates, self mutilation. This can also result in skewed observational data when observing marine mammal behavior in captivity, as often times there is little natural behavior exhibited by cetaceans in captive environments. Additionally, because of the difficulties associated with replicating natural social structures and habitats in captivity, this disallows these animals to engage in natural behaviors such as deep-diving, (specialized) foraging behavior, dispersal, long-term social associations, etc. which can further exacerbate stress. (Perrin et al., 2009; Rose et al., 2009; Jett & Ventre, 2011)

Increased mortality; many cetaceans on average live drastically shorter lifespans in captivity than their wild counterparts, despite being kept in relatively sterile environments free of contaminants, predators, and other threats present in their natural environments. This is particularly noticeable in pilot whales, orcas, bottlenose dolphins, and belugas. (DeMaster and Drevenak, 1988; Jett & Ventre, 2011; NOAA’s National Marine Mammal Inventory, 2016)

Expensive/logistically difficult to maintain marine mammals; Marine mammals require spacious habitats with powerful filtration systems to be properly maintained, however, even with these factors accounted for, it become difficult to satisfy the dietary, environmental, and social needs of cetaceans in particular in an artificial environment (Perrin et al. 2009). Some animals are incredibly specialized hunters, gregarious and sociable, or originate from marine habitats that can be difficult to replicate on the large scale (deep, pelagic environments, or dynamic coastal environments, for example). Some aquariums have attempted to incorporate kelp forests and natural substrates in aquaria, while maintaining multiple species of live, schooling fish (for example) to stimulate hunting behavior, but this is not a common practice across the board.

Stimulates commercial industry; the display of captive cetaceans can be the inspiration for developing countries and regions outside of North America to begin their own captive whale and dolphin trade for commercial purposes. Dolphinariums are popular tourist attractions that annually generate millions of dollars in revenue, and these marine parks and aquariums, as well as the fisheries that supply wild-caught animals, can help stimulate local economies. This is both a good thing and a bad thing, as developing countries can greatly benefit from job production and economy stimulation, but this can also put unnecessary pressures on wild stocks of marine mammals and may lead to the collapse of some populations of whales and dolphins such as in the case of the Southern Resident orcas of Puget Sound in the 60′s and 70′s when marine parks were rising in popularity across North America.

Sends the wrong message (Questionable ethics/“respect” for nature); Again, this is personal bias, but I think it illustrates the issues that surround public exposure to marine mammal captivity. When I first was introduced to whales and dolphins in an aquarium setting, I was not inspired to work with them in the wild, but rather wanted to train captive orcas and be in the water with them. When we view marine mammals in captivity (or at least, prior to Blackfish), we see a positive image of keeping these animals in captivity. It also masks the complications and dangers that are associated with their captive maintenance through the use of marketing and PR tactics to hold these aquarium facilities and marine parks in a positive light while ignoring some of the hard and blatant realities of this practice. My love for other marine animals like many of the great whales and oceanic sharks did not stem from seeing them in an aquarium, but rather from reading about them in field guides and watching them in their natural habitats through documentaries. Additionally, with today’s technological advances in the virtual reality and animatronics, as well as the use of films, preserved specimens and museum-quality replicas and models, one can create an educational and entertaining exhibition without the unethical and dangerous use of live animals in aquaria. Attitudes continue to change in the wake of public enlightenment regarding the captivity industry, and I can only hope we rightly shift our attentions from the animals in captivity to the ones in the wild where it really matters in the grand scheme of things. I’m not saying forget about the captives, in facts many still need our help when it comes to holding these facilities accountable for their husbandry practices and contributions to research and conservation. But we are at the risk of losing the world’s oceans, and we need to address that now.

What do you guys think about captivity? For research and conservation? For commercial purposes?

#captivity#marine mammals#cetaceans#whale#dolphin#sea world#aquarium#marine park#blackfish#anti captivity#pro captivity#marine biology#biology#science#conservation

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Work with Simple Machines

Photo from Winkbooks.net

DK How Machines Work: Zoo Break

Written and Illustrated by David Macauley

Published by Penguin Random House

2015

Won the Royal Society’s Young People’s Book Prize

American Institute of Physics Science Writing Award for Writing for Children (2016)

Meet Sloth and Sengi, two zoo animals who are bored with captivity. In this ingenious introduction to simple machines, kids can use pop up components to conduct hands-on-experiments and engage in scientific inquiry while they help the main characters escape.

The characters in the story experiment with creating different devices to free themselves, first trying to wedge open a door, then trying to get over the fence with a lever and even later, building a flying machine! This problem and solution structure is enhanced by the hands-on attributes and allows children to extrapolate, asking questions and running their own experiments with Sengi and Sloth.

This book is directed toward children in grades 2-5. That is about right. The introduction of the manipulative elements will attract children in the younger grades who need a kinesthetic experience in order to grasp how these machines work. Here, readers can use a pop-out plank and a pop-up fulcrum to build a simple lever and pop Sengi and Sloth over the fence.

Photo courtesy of Amazon.com

And the American Institute of Physics reported that “Readers interact with the characters and the different types of simple machines. We especially liked the pop-up and removable interactive components in this book, which can be used to introduce children to basic physics and engineering principles or to introduce inquiry science lessons involving simple machines.”

This interactive narrative non-fiction picture book meets the criteria for non-fiction in the way only David Macauley can. The organizational structure is simple and easy to navigate. Big headings in the top corners of each page like “Inclined to Escape” on page 4 introduces scientific vocabulary children need to know. The heading is followed by expository text and the language is sophisticated, geared toward the older readers in grades 4-6.

“An inclined plane is essentially a sloped surface. It makes climbing easier by making the climb less steep. Even though the distance is increased, the effort needed is much less.”

A full-bleed glossary is included on pages 28-29 in case readers need clarification about these terms.

While the language and the story are a key component for the reader it is the pictures and layout that really make this book effective for a wide variety of readers. Information is delivered in small chunks across richly illustrated pages. Small circles and squares are set out from the text and contain illustrations that offer close up details for the reader to analyze such as on page 20 when the concept of a screw is explained in words and pictures. An oval inset shows how to wrap a length of hose around a stick, taking advantage of the qualities of the inclined plane to make an Archimedes Screw that moves water. The simple illustration makes the complicated concept clearer.

The illustrations are whimsical, with lots of little lines to demonstrate detail and movement and a muted palette of colors, greens and greys and browns that keep the busy pages from becoming overwhelming.

Photo: Hadley Roberts, (2019)

The other reason I love this book is the subtle payoff kids get from lifting flaps and digging deeper into the content. On the page about the Archimedes screw, the name Archimedes is only found by lifting up a flap that looks like Sloth. Inside a fold-out explains how screw pumps have been found throughout history, designed by Archimedes but also possibly found in Babylon.

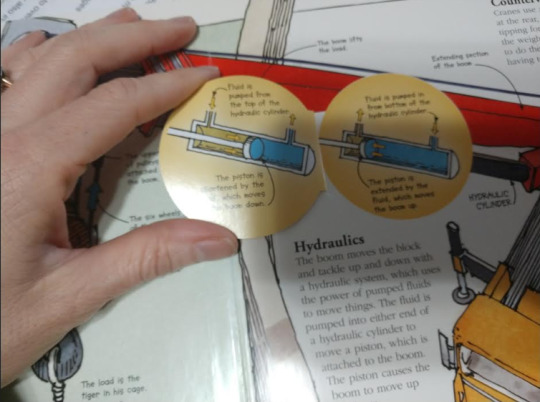

On the page before a similar flap uses tiny pictures to explain exactly how fluid functions in a hydraulic pump.

The simple text reads “Fluid is pumped from the top of the hydraulic cylinder. The piston is shortened by the fluid which moves the boom down.” Arrows guide the reader through the process, offering further visual clues, even though the language is fairly simple and the glossary exists to clear up the more complex terms.

Yet another booklet explains gears. And in this one, a subtle background of graph paper lends a feel of authority and a dash of the engineering environment to the concept.

But the characters of Sloth and Sengi lend whimsy and fun to the serious concepts. Sight gags like Sloth explaining that he’s “not cut out for this” while he is pictured sawing a board adds age-appropriate humor to the mix.

The characters are pretty flat, They have simple personalities. Sengi is the brainy one who always innovates and Sloth is the funny, one but this is done intentionally so that the reader doesn’t get too wrapped up in the narrative and instead focuses on the machines and their own interactive role in the story.

The book culminates with Sengi masterminding a major build, a complex machine that combines all the elements discussed throughout the book. The foldout drawing of Sengi’s machine is enormous, About two feet by one and a half feet. It uses numbered arrows to direct the reader and though it lacks text this encourages the reader to think carefully about each aspect of this giant device.

This book would be a great addition to a center in a classroom and could be further enhanced with the edition of a table full of objects, Keva planks, twine, pulleys, cardboard and pegs, sticks, and Lincoln logs that could be used to extend the play this book encourages.

Books to pair with this include:

Gizmos and Gadgets: Creating Science Contraptions That Work (And Knowing Why)

by Jill Frankel Hauser

Williamson Books, Nashville Tennessee

1999

This is an older book but science never goes out of style. An activity book with instructions for 50 working contraptions to play with. I love this book because it uses simple everyday objects to explain science concepts, like on page 32 “You can learn a lot about friction by exploring the soles of footgear. Check out these shoes and think about their uses: basketball shoes, hiking shoes, cleated shoes for baseball and soccer, ballet slippers, rain boots, and skates.”

The black and white illustrations are simple and easy to follow. An index and back matter suggest more books to turn to for ideas.

Cao Chong Weighs an Elephant

By Songju Ma Daemicke

Illustrated by Christina Wald

Best STEM Books of 2018 for K-12 Selection by NSTA, ITEEA & CBC Outstanding Science Trade Books Selection of 2018 by NSTA & CBC Notable-Social-Studies books of 2018 selection by NCSS &CBC A Mathical Honor Books of 2018 by MSRI, NCTM & CBC< Children's Book Council "Book Power" Showcase selection

This book tells the classic Chinese tale of a child prodigy and his unique solution to a scientific problem.

The Frank Einstein Series

Author: John Scieszka

Illustrator: Brian Biggs

Publisher: Penguin Random House

Science-tinged fiction for the 7-10 set

Kid inventor Frank Einstein and his two robots, Klink and Klank mix science, adventure, and slapstick into this entertaining set of six books.

For older kids who are exploring these concepts this YA biographical fiction about Archimedes sounds like a snorer. but it is really not!The Sand Reckoner by Gillian Bradshaw is worth a look! I read for two days straight and couldn’t put it down.

0 notes

Text

Pass Go and Collect $200: The Real Story of How Monopoly Was Invented

Author: Tanya Lee Stone

Illustrator: Steven Salerno

Publisher: Henry Holt and Company

Publication Year: 2018

Awards:

A Kirkus Best Book of the Year

An ALSC Notable Book

An NCTE Orbus Pictus Honor Book

An NCSS Notable Social Studies Trade Book for Young People

A Chicago Public Library Best Book of the Year

An Amazon Best Book of the Month

A CCBC Choice Title

An ALSC Notable Title

Brief Summary: In the late 1800s lived Lizzie Magie, a clever and charismatic woman with a strong sense of justice. Waves of urban migration drew Lizzie’s attention to rising financial inequality. One day she had an idea: create a game that shows the unfairness of the landlord-tenant relationship. But game players seemed to have the most fun pretending to be wealthy landowners. Enter Charles Darrow, a marketer and salesman with a vision for transforming Lizzie’s game into an exciting staple of American family entertainment. Features back matter that includes "Monopoly Math" word problems and equations. Excellent STEM connections and resources.

Ideas for using this book in classroom or library: STEM program

Special features included (if applicable) – Tremendous Trivia, Monopoly Math, A Note from the Author, Sources

Where I Accessed The Book: Blount County Public Library (J 794 STO)

0 notes

Text

Gwendolyn Brooks and Jan Spivey Gilchrist's WE ARE SHINING is among the 2018 Notable Social Studies Trade Book for Young People

We are pleased to report that WE ARE SHINING (HarperCollins), penned by the late poet laureate and Pulitzer Prize winner, Gwendolyn Brooks and illustrated by Coretta Scott King Award-winner, Jan Spivey Gilchrist, is among the 2018 Notable Social Studies Trade Book for Young People in the K-2 category.

Jan Spivey Gilchrist has a good deal of experience speaking to many different types of audiences and is available for presentations to home schooling groups, conferences, festivals and children in school settings. For descriptions of her programs and other details, visit Balkin Buddies or give us a call. We’re always happy to help.

#Picture book#picture book poetry#gwendolyn brooks#2019 Coretta Scott King Honor Award#we are shining#jan spivey gilchrist#u.s. poet laureate#pulitzer prize winner#african american poet#african american poetry#african american picture book#diveristy#shared humanity#life-affirming#illustrator appearances#illustrator visits#school visits#educational conferences#home schooling groups#library conferences#2018 Notable Social Studies Trade Books for Young People#balkin buddies

0 notes

Link

Danielle A. Jackson | Longreads | September 2019 | 16 minutes (4,184 words)

The late summer night Tupac died, I listened to All Eyez on Me at a record store in an East Memphis strip mall. The evening felt eerie and laden with meaning. It was early in the school year, 1996, and through the end of the decade, Adrienne, Jessica, Karida and I were a crew of girlfriends at our high school. We spent that night, and many weekend nights, at Adrienne’s house.

Our public school had been all white until a trickle of black students enrolled during the 1966–67 school year. That was 12 years after Brown v. Board of Education and six years after the local NAACP sued the school board for maintaining dual systems in spite of the ruling. In 1972, a federal district court ordered busing; more than 40,000 white students abandoned the school system by 1980. The board created specialized and accelerated courses in some of its schools, an “optional program,” in response. Students could enter the programs regardless of district lines if they met certain academic requirements. This kind of competition helped retain some white students, but also created two separate tracks within those institutions — a tenuous, half-won integration. It meant for me, two decades later, a “high-performing school” with a world of resources I knew to be grateful for, but at a cost. There were few black teachers. Black students in the accelerated program were scattered about, small groups of “onlies” in all their classes. Black students who weren’t in the accelerated program got rougher treatment from teachers and administrators. An acrid grimness hung in the air. It felt like being tolerated rather than embraced.

My friends and I did share a lunch period. At our table, we traded CDs we’d gotten in the mail: Digable Planets’s Blowout Comb, D’Angelo’s Brown Sugar, the Fugees’ The Score. An era of highly visible black innovation was happening alongside a growing awareness of my own social position. I didn’t have those words then, but I had my enthusiasms. At Maxwell’s concert one sweaty night on the Mississippi, we saw how ecstasy, freedom, and black music commingle and coalesce into a balm. We watched the films of the ’90s wave together, and while most had constraining gender politics, Love Jones, the Theodore Witcher–directed feature about a group of brainy young artists in Chicago, made us wish for a utopic city that could make room for all we would become.

Kickstart your weekend reading by getting the week’s best Longreads delivered to your inbox every Friday afternoon.

Sign up

We also loved to read the glossies — what ’90s girl didn’t? We especially salivated over every cover of Vibe. Adrienne and I were fledgling writers who experimented a lot and adored English class. In the ’90s, the canon was freshly expanding: We read T.S. Eliot alongside Kate Chopin and Chinua Achebe. Something similar was happening in magazines. Vibe’s mastheads and ad pages were full of black and brown people living, working, and loving together and out front — a multicultural ideal hip-hop had made possible. Its “new black aesthetic” meant articles were fresh and insightful but also hyper-literary art historical objects in their own rights. Writers were fluent in Toni Morrison and Ralph Ellison as well as Biggie Smalls. By the time Tupac died, Kevin Powell had spent years contextualizing his life within the global struggle for black freedom. “There is a direct line from Tupac in a straitjacket [on the popular February 1994 cover] to ‘It’s Obama Time’ [the September 2007 cover, one of the then senator’s earliest],” former editor Rob Kenner told Billboard in a Vibe oral history. He’s saying Vibe helped create Obama’s “coalition of the ascendent” — the black, Latinx, and young white voters who gave the Hawaii native two terms. For me, the pages reclaimed and retold the American story with fewer redactions than my history books. They created a vision of what a multiethnic nation could be.

* * *

“There was a time when journalism was flush,” Danyel Smith told me on a phone call from a summer retreat in Massachusetts. She became music editor at Vibe in 1994, and was editor in chief during the late ’90s and again from 2006 to 2008. The magazine, founded by Quincy Jones and Time, Inc. executives in 1992, was the “first true home of the culture we inhabit today,” according to Billboard. During Smith’s first stint as editor in chief, its circulation more than doubled. She wrote the story revealing R. Kelly’s marriage to then 15-year-old Aaliyah, as well as cover features on Janet Jackson, Wesley Snipes, and Whitney Houston. Smith was at the helm when the magazine debuted its Obama covers in 2007 — Vibe was the first major publication to endorse the freshman senator. When she described journalism as “flush,” Smith was talking about the late ’80s, when she started out in the San Francisco Bay. “Large cities could support with advertising two, sometimes three, alternative news weeklies and dailies,” she said.

‘There is a direct line from Tupac in a straitjacket [on the popular February 1994 cover] to ‘It’s Obama Time’ [the September 2007 cover, one of the then senator’s earliest].’

The industry has collapsed and remade itself many times since then. Pew reports that between 2008 and 2018, journalism jobs declined 25 percent, a net loss of about 28,000 positions. Business Insider reports losses at 3,200 jobs this year alone. Most reductions have been in newspapers. A swell in digital journalism has not offset the losses in print, and it’s also been volatile, with layoffs several times over the past few years, as outlets “pivot to video” or fail to sustain venture-backed growth. Many remaining outlets have contracted, converting staff positions into precarious freelance or “permalance” roles. In a May piece for The New Republic, Jacob Silverman wrote about the “yawning earnings gap between the top and bottom echelons” of journalism reflected in the stops and starts of his own career. After a decade of prestigious headlines and publishing a book, Silverman called his private education a “sunken cost” because he hadn’t yet won a coveted staff role. If he couldn’t make it with his advantageous beginnings, he seemed to say, the industry must be truly troubled. The prospect of “selling out” — of taking a corporate job or work in branded content — seemed more concerning to him than a loss of the ability to survive at all. For the freelance collective Study Hall, Kaila Philo wrote how the instability in journalism has made it particularly difficult for black women to break into the industry, or to continue working and developing if they do. The overall unemployment rate for African Americans has been twice that of whites since at least 1972, when the government started collecting the data by race. According to Pew, newsroom employees are more likely to be white and male than U.S. workers overall. Philo’s report mentions the Women’s Media Center’s 2018 survey on women of color in U.S. news, which states that just 2.62 percent of all journalists are black women. In a write-up of the data, the WMC noted that fewer than half of newspapers and online-only newsrooms had even responded to the original questionnaire.

* * *

According to the WMC, about 2.16 percent of newsroom leaders are black women. If writers are instrumental in cultivating our collective conceptions of history, editors are arguably more so. Their sensibilities influence which stories are accepted and produced. They shape and nurture the voices and careers of writers they work with. It means who isn’t there is noteworthy. “I think it’s part of the reason why journalism is dying,” Smith said. “It’s not serving the actual communities that exist.” In a July piece for The New Republic, Clio Chang called the push for organized labor among freelancers and staff writers at digital outlets like Vox and Buzzfeed, as well as at legacy print publications like The New Yorker, a sign of hope for the industry. “In the most basic sense, that’s the first norm that organizing shatters — the isolation of workers from one another,” Chang wrote. Notably, Vox’s union negotiated a diversity initiative in their bargaining agreement, mandating 40 to 50 percent of applicants interviewed come from underrepresented backgrounds.

“Journalism is very busy trying to serve a monolithic imaginary white audience. And that just doesn’t exist anymore,” Smith told me. U.S. audiences haven’t ever been truly homogeneous. But the media institutions that serve us, like most facets of American life, have been deliberately segregated and reluctant to change. In this reality, alternatives sprouted. Before Vibe’s launch, Time, Inc. executives wondered whether a magazine focused on black and brown youth culture would have any audience at all. Greg Sandow, an editor at Entertainment Weekly at the time, told Billboard, “I’m summoned to this meeting on the 34th floor [at the Time, Inc. executive offices]. And here came some serious concerns. This dapper guy in a suit and beautifully polished shoes says, ‘We’re publishing this. Does that mean we have to put black people on the cover?’” Throughout the next two decades, many publications serving nonwhite audiences thrived. Vibe spun off, creating Vibe Vixen in 2004. The circulations of Ebony, JET, and Essence, legacy institutions founded in 1945, 1951, and 1970, remained robust — the New York Times reported in 2000 that the number of Essence subscribers “sits just below Vogue magazine’s 1.1 million and well above the 750,000 of Harper’s Bazaar.” One World and Giant Robot launched in 1994, Latina and TRACE in 1996. Honey’s preview issue, with Lauryn Hill on the cover, hit newsstands in 1999. Essence spun off to create Suede, a fashion and culture magazine aimed at a “polyglot audience,” in 2004. A Magazine ran from 1989 to 2001; Hyphen launched with two young reporters at the helm the following year. In a piece for Columbia Journalism Review, Camille Bromley called Hyphen a celebration of “Asian culture without cheerleading” invested in humor, complication, and complexity, destroying the model minority myth. Between 1956 and 2008, the Chicago Defender, founded in 1905 and a noted, major catalyst for the Great Migration, published a daily print edition. During its flush years, the Baltimore Afro-American, founded in 1892, published separate editions in Philadelphia, Richmond, and Newark.

Before Vibe’s launch, Time, Inc. executives wondered whether a magazine focused on black and brown youth culture would have any audience at all.

The recent instability in journalism has been devastating for the black press. The Chicago Defender discontinued its print editions in July. Johnson Publications, Ebony and JET’s parent company, filed bankruptcy earlier this year after selling the magazines to a private equity firm in 2016. Then it put up for sale its photo archive — more than 4 million prints and negatives. Its record of black life throughout the 20th century includes images of Emmett Till’s funeral, in which the 14-year-old’s mutilated body lay in state, and Moneta Sleet Jr.’s Pulitzer Prize–winning image of Coretta Scott King mourning with her daughter, Bernice King. It includes casually elegant images of black celebrities at home and shots of everyday street scenes and citizens — the dentists and mid-level diplomats who made up the rank and file of the ascendant. John H. Johnson based Ebony and JET on LIFE, a large glossy heavy on photojournalism with a white, Norman Rockwell aesthetic and occasional dehumanizing renderings of black people. Johnson’s publications, like the elegantly attired stars of Motown, were meant as proof of black dignity and humanity. In late July, four large foundations formed an historic collective to buy the archive, shepherd its preservation, and make it available for public access.

The publications’ written stories are also important. Celebrity profiles offered candid, intimate views of famous, influential black figures and detailed accounts of everyday black accomplishment. Scores of skilled professionals ushered these pieces into being: Era Bell Thompson started out at the Chicago Defender and spent most of her career in Ebony’s editorial leadership. Tennessee native Lynn Norment worked for three decades as a writer and editor at the publication. André Leon Talley and Elaine Welteroth passed through Ebony for other jobs in the industry. Taken together, their labor was a massive scholarly project, a written history of a people deemed outside of it.

Black, Latinx, and Asian American media are not included in the counts on race and gender WMC reports. They get their data from the American Society of News Editors (ASNE), and Cristal Williams Chancellor, WMC’s director of communications, told me she hopes news organizations will be more “aggressive” in helping them “accurately indicate where women are in the newsroom.” While men dominate leadership roles in mainstream newsrooms, news wires, TV, and audio journalism, publications targeting multicultural audiences have also had a reputation for gender trouble, with a preponderance of male cover subjects, editorial leaders, and features writers. Kim Osorio, the first woman editor in chief at The Source, was fired from the magazine after filing a complaint about sexual harassment. Osorio won a settlement for wrongful termination in 2006 and went on to help launch BET.com and write a memoir before returning to The Source in 2012. Since then, she’s made a career writing for TV.

* * *

This past June, Nieman Lab published an interview with Jeffrey Goldberg, editor in chief of The Atlantic since 2016, and Adrienne LaFrance, the magazine’s executive editor. The venerable American magazine was founded in Boston in 1857. Among its early supporters were Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, and Harriet Beecher Stowe. It sought to promote an “American ideal,” a unified yet pluralistic theory of American aesthetics and politics. After more than a century and a half of existence, women writers are not yet published in proportion to women’s share of the country’s population. The Nieman piece focused on progress the magazine has made in recent years toward equitable hiring and promoting: “In 2016, women made up just 17 percent of editorial leadership at The Atlantic. Today, women account for 63 percent of newsroom leaders.” A few days after the piece’s publication, a Twitter user screen-capped a portion of the interview where Goldberg was candid about areas in which the magazine continues to struggle:

GOLDBERG: We continue to have a problem with the print magazine cover stories — with the gender and race issues when it comes to cover story writing. [Of the 15 print issues The Atlantic has published since January 2018, 11 had cover stories written by men. — Ed.]

It’s really, really hard to write a 10,000-word cover story. There are not a lot of journalists in America who can do it. The journalists in America who do it are almost exclusively white males. What I have to do — and I haven’t done this enough yet — is again about experience versus potential. You can look at people and be like, well, your experience is writing 1,200-word pieces for the web and you’re great at it, so good going!

That’s one way to approach it, but the other way to approach it is, huh, you’re really good at this and you have a lot of potential and you’re 33 and you’re burning with ambition, and that’s great, so let us put you on a deliberate pathway toward writing 10,000-word cover stories. It might not work. It often doesn’t. But we have to be very deliberate and efficient about creating the space for more women to develop that particular journalistic muscle.

My Twitter feed of writers, editors, and book publicists erupted, mostly at the excerpt’s thinly veiled statement on ability. Women in my timeline responded with lists of writers of longform — books, articles, and chapters — who happened to be women, or people of color, or some intersection therein. Goldberg initially said he’d been misquoted. When Laura Hazard Owen, the deputy editor at Nieman who’d conducted the interview, offered proof that Goldberg’s statements had been delivered as printed, he claimed he had misspoken. Hazard Owen told the L.A. Times she believes that The Atlantic is, overall, “doing good work in diversifying the staff there.”

Taken together, their labor was a massive scholarly project, a written history of a people deemed outside of it.

Still, it’s a difficult statement for a woman writer of color to hear. “You literally are looking at me and all my colleagues, all my women colleagues and all my black colleagues, all my colleagues of color and saying, ‘You’re not really worthy of what we do over here.’ It’s mortifying,” Smith told me. Goldberg’s admission may have been a misstatement, but it mirrors the continued whiteness of mainstream mastheads. It checks out with the Women’s Media Center’s reports and the revealing fact of how much data is missing from even those important studies. It echoes the stories of black women who work or worked in journalism, who have difficulty finding mentors, or who burn out from the weight of wanting to serve the chronically underserved. It reflects my own experiences, in which I have been told multiple times in a single year that I am the only black woman editor that a writer has ever had. But it doesn’t corroborate my long experience as a reader. What happened to the writers and editors and multihyphenates from the era of the multicultural magazine, that brief flash in the 90’s and early aughts when storytellers seemed to reflect just how much people of color lead in creating American culture? Who should have formed a pipeline of leaders for mainstream publications when the industry began to contract?

* * *

In addition to her stints at Vibe, Smith also edited for Billboard, Time, Inc. publications, and published two novels. She was culture editor for ESPN’s digital magazine The Undefeated before going on book leave. Akiba Solomon is an author, editor of two books, and is currently senior editorial director at Colorlines, a digital news daily published by Race Forward. She started an internship at YSB in 1995 before going on to write and edit for Jane, Glamour, Essence, Vibe Vixen, and The Source. She told me that even at magazines without predominantly black staff, she’d worked with other black people, though not often directly. At black magazines, she was frequently edited by black women. “I’ve been edited by Robin Stone, Vanessa DeLuca [formerly editor-in-chief of Essence, currently running the Medium vertical ZORA], Ayana Byrd, Kierna Mayo, Cori Murray, and Michaela Angela Davis.” Solomon’s last magazine byline was last year, an Essence story on black women activists who organize in culturally relevant ways to fight and prevent sexual assault.

Solomon writes infrequently for publications now, worn down by conditions in journalism she believes are untenable. At the hip-hop magazines, the sexism was a deterrent, and later, “I was seeing a turn in who was getting the jobs writing about black music” when it became mainstream. “Once folks could divorce black music from black culture it was a wrap,” she said. At women’s magazines, Solomon felt stifled by “extremely narrow” storytelling. Publishing, in general, Solomon believes, places unsustainable demands on its workers.

When we talk about the death of print, it is infrequent that we also talk about the conditions that make it ripe for obsolescence. The reluctant slowness with which mainstream media has integrated its mastheads (or kept them integrated) has meant the industry’s content has suffered. And the work environments have placed exorbitant burdens on the people of color who do break through. In Smith’s words:

You feel that you want to serve these people with good and quality content, with good and quality graphics, with good and quality leadership. And as a black person, as a black woman, regardless of whether you’re serving a mainstream audience, which I have at a Billboard and at Time, Inc., or a multicultural audience, which I have at Vibe, it is difficult. And it’s actually taken me a long time to admit that to myself. It does wear you down. And I ask myself why have I always, always stayed in a job two and a half to three years, especially when I’m editing? It’s because I’m tired by that time.

In a July story for Politico, black journalists from The New York Times and the Associated Press talked about how a sophisticated understanding of race is critical to ethically and thoroughly covering the current political moment. After the August 3 massacre in El Paso, Lulu Garcia-Navarro wrote how the absence of Latinx journalists in newsrooms has created a vacuum that allows hateful words from the president to ring unchallenged. Lacking the necessary capacity, many organizations cover race related topics, often matters of life and death, without context or depth. As outlets miss the mark, journalists of color may take on the added work of acting as the “the black public editor of our newsrooms,” Astead Herndon from the Times said on a Buzzfeed panel. Elaine Welteroth wrote about the physical exhaustion she experienced during her tenure as editor in chief at Teen Vogue in her memoir More Than Enough. She was the second African American editor in chief in parent company Condé Nast’s 110 year history:

I was too busy to sleep, too frazzled to eat, and TMI: I had developed a bizarre condition where I felt the urge to pee — all the time. It was so disruptive that I went to see a doctor, thinking it may have been a bladder infection.

Instead, I found myself standing on a scale in my doctor’s office being chastised for accidentally dropping nine more pounds. These were precious pounds that my naturally thin frame could not afford to lose without leaving me with the kind of bony body only fashion people complimented.

Condé Nast shuttered Teen Vogue’s print edition in 2017, despite record-breaking circulation, increased political coverage, and an expanded presence on the internet during Welteroth’s tenure. Welteroth left the company to write her book and pursue other ventures.

Mitzi Miller was editor in chief of JET when it ran the 2012 cover story on Jordan Davis, a Florida teenager shot and killed by a white vigilante over his loud music. “At the time, very few news outlets were covering the story because it occurred over a holiday weekend,” she said. To write the story, Miller hired Denene Millner, an author of more than 20 books. With interviews from Jordan’s parents, Ron Davis and Lucy McBath, the piece went viral and was one of many stories that galvanized the contemporary American movement against police brutality.

Miller started working in magazines in 2000, and came up through Honey and Jane before taking the helm at JET then Ebony in 2014. She edits for the black website theGrio when she can and writes an occasional piece for a print magazine roughly once a year. Shrinking wages have made it increasingly difficult to make a life in journalism, she told me. After working at a number of dream publications, Miller moved on to film and TV development.

Both Miller and Solomon noted how print publications have been slow to evolve. “It’s hard to imagine now, particularly to digital native folks, but print was all about a particular format. It was about putting the same ideas into slightly different buckets,” Solomon said. On the podcast Hear to Slay, Vanessa DeLuca spoke about how reluctant evolution may have imperiled black media. “Black media have not always … looked forward in terms of how to build a brand across multiple platforms.” Some at legacy print institutions still seem to hold internet writing in lower esteem (“You can look at people and be like, well, your experience is writing 1,200-word pieces for the web and you’re great at it, so good going!” were Goldberg’s words to Nieman Lab). Often, pay structures reflect this hierarchy. Certainly, the internet’s speed and accessibility have lowered barriers to entry and made it such that rigor is not always a requirement for publication. But it’s also changed information consumption patterns and exploded the possibilities of storytelling.

Michael Gonzales, a frequent contributor to this site and a writer I’ve worked with as an editor, started in magazines in the 1980s as a freelancer. He wrote for The Source and Vibe during a time that overlapped with Smith’s and Solomon’s tenures, the years now called “the golden era of rap writing.” The years correspond to those moments I spent reading magazines with my high school friends. At black publications, he worked with black women editors all the time, but “with the exception of the Village Voice, none of the mainstream magazines employed black editors.” Despite the upheaval of the past several years (“the money is less than back in the day,” he said), Gonzales seems pleased with where his career has landed, “I’ve transformed from music critic/journalist to an essayist.” He went on to talk about how now, with the proliferation of digital magazines:

I feel like we’re living in an interesting writer time where there are a number of quality sites looking for quality writing, especially in essay form. There are a few that sometimes get too self-indulgent, but for the most part, especially in the cultural space (books, movies, theater, music, etc.), there is a lot of wonderful writing happening. Unfortunately you are the only black woman editor I have, although a few years back I did work with Kierna Mayo at Ebony.

* * *

Danielle A. Jackson is a contributing editor at Longreads.

Editor: Sari Botton

Fact checker: Steven Cohen

Copy editor: Jacob Z. Gross

0 notes

Text

Seven Sisters' Surge: Applications to Women’s Colleges Spike

Women are breaking records in 2019: six women so far are running for president, 127 women are serving in Congress and there has been a significant increase in applications to women’s colleges.

Over the past five years, Barnard College, the women's college of Columbia University, has seen a 64% increase in applications.

Japan Says Name for New Era of Naruhito Will Be 'Reiwa'

"Barnard has continued to widen its reach nationally and globally to find young women who are intellectually engaged, who want to impact the world around them and appreciate the unique qualities Barnard presents," Barnard’s vice president for enrollment Jennifer Fondiller said.

Barnard is not the only women’s college that has seen a sharp increase in applications. Over the past five years, applications at three elite institutions in Massachusetts have also spiked: Mount Holyoke was up 23.6%, Smith 25% and Wellesley 40%. Admissions at Bryn Mawr in Pennsylvania went up by 23.1%.

US Man Charged With Trying to Steal Item From Auschwitz

Mount Holyoke President Sonya Stephens believes there are many factors that contribute to the rise, "including but not limited to a growth in interest in social movements," she said.

Joy St. John, dean of admission and financial aid at Wellesley said, "We've seen growth in applications from every major geographic region; and among our most recently accepted class, 57% are domestic students of color and 17% are the first in their families to attend a four-year college."

American Airlines Holds Mock Flight for Children With Autism

Nathan Grawe, author of the book "Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education," said the surge in women's college applications "is particularly notable given that in the country as a whole, we are in a time of stable to falling numbers of high school graduates."

He said that while changes to the admissions process can affect the numbers, "on the face of it, a surge in applications over the last five years makes you sit up and ask, 'What is causing this?'"

A study called "What Matters in College After College" prepared for the Women’s College Coalition found that women’s colleges alumnae were more likely than any other group to complete a graduate degree. The study also found that women’s colleges receive higher effectiveness ratings than all other colleges and universities for helping students be prepared for their first job.

These statistics do not surprise students like Barnard senior Xonatia Lee. “When women are exposed to powerful female role models, they are more likely to endorse the notion that women are well suited for a leadership role," Lee said. "It is important to invest in a women’s education and build their leadership skills."

Students who graduate from women’s colleges have high success rates in the workforce. Barnard’s class of 2018 had a 93 percent placement rate in work or graduate schools.

Barnard College president Sian Beilock explained, "We attract fantastic young women and then we work to make them even better and more inspired."

Martha Casey, a lawyer who graduated from Wellesley College in 1977, said she finds women who went to women’s colleges working on Capitol Hill, in top law firms, and trade associations.

"Wellesley grads are just everywhere. I think that they step easily into leadership positions," Casey said. “When we were running our school, dominating our own classes, and interacting with one another as undergrads, it seemed natural to us."

Rebecca Glass, a senior at Barnard College, never thought she would end up attending a women’s college. She started her education at Penn State and decided to transfer because she felt "the social infrastructure [Greek life] relied on disempowering women."

At Barnard, Glass said she feels constantly empowered as she is always "surrounded by women who are so ambitious, inspirational, kind, and supportive; it is the exact opposite."

"We need women’s colleges in order to continue to bolster, strengthen, and uplift young women today, especially women who are not upper middle class and white," Glass told NBC.

Glass is not the only woman who has had this experience. Amy Iwanowicz, a recent graduate of Smith College, a women’s liberal arts school in Massachusetts, transferred to Smith after a year at Syracuse. “At Syracuse a lot of people rallied around sports and I think at Smith people rallied around ideals,” she said.

"Even though women have made so much progress, I think that women are still facing things like being scared to speak up in the classroom, they feel like they are overshadowed by men," Iwanowicz said. "Women’s colleges have historically served as a place to empower and inspire women."

In the 1960s, the United States had 281 women's colleges. With the exception of Cornell, most Ivy League Schools were not fully co-ed until the 1970s. In fact, Columbia University’s undergraduate college did not start accepting women until 1983.

Today there are approximately 34 active women’s colleges in the United States. The most predominant of these colleges are known as the Seven Sisters. Five of the seven institutions are still all-female colleges today: Barnard College, Bryn Mawr College, Mount Holyoke College, Smith College and Wellesley College. Vassar College became a co-ed college in 1969 and Radcliffe become fully merged with Harvard in 1999.

"In a time in our world where we are talking about the importance of having women in leadership roles, having women at the table, a place that focuses on empowering women is a great place to start," said Beilock.

Photo Credit: Emma Barnett/NBC This story uses functionality that may not work in our app. Click here to open the story in your web browser. Seven Sisters' Surge: Applications to Women’s Colleges Spike published first on Miami News

0 notes

Text

When American Media Was (Briefly) Diverse

Danielle A. Jackson | Longreads | September 2019 | 16 minutes (4,184 words)

The late summer night Tupac died, I listened to All Eyez on Me at a record store in an East Memphis strip mall. The evening felt eerie and laden with meaning. It was early in the school year, 1996, and through the end of the decade, Adrienne, Jessica, Karida and I were a crew of girlfriends at our high school. We spent that night, and many weekend nights, at Adrienne’s house.

Our public school had been all white until a trickle of black students enrolled during the 1966–67 school year. That was 12 years after Brown v. Board of Education and six years after the local NAACP sued the school board for maintaining dual systems in spite of the ruling. In 1972, a federal district court ordered busing; more than 40,000 white students abandoned the school system by 1980. The board created specialized and accelerated courses in some of its schools, an “optional program,” in response. Students could enter the programs regardless of district lines if they met certain academic requirements. This kind of competition helped retain some white students, but also created two separate tracks within those institutions — a tenuous, half-won integration. It meant for me, two decades later, a “high-performing school” with a world of resources I knew to be grateful for, but at a cost. There were few black teachers. Black students in the accelerated program were scattered about, small groups of “onlies” in all their classes. Black students who weren’t in the accelerated program got rougher treatment from teachers and administrators. An acrid grimness hung in the air. It felt like being tolerated rather than embraced.

My friends and I did share a lunch period. At our table, we traded CDs we’d gotten in the mail: Digable Planets’s Blowout Comb, D’Angelo’s Brown Sugar, the Fugees’ The Score. An era of highly visible black innovation was happening alongside a growing awareness of my own social position. I didn’t have those words then, but I had my enthusiasms. At Maxwell’s concert one sweaty night on the Mississippi, we saw how ecstasy, freedom, and black music commingle and coalesce into a balm. We watched the films of the ’90s wave together, and while most had constraining gender politics, Love Jones, the Theodore Witcher–directed feature about a group of brainy young artists in Chicago, made us wish for a utopic city that could make room for all we would become.

Kickstart your weekend reading by getting the week’s best Longreads delivered to your inbox every Friday afternoon.

Sign up