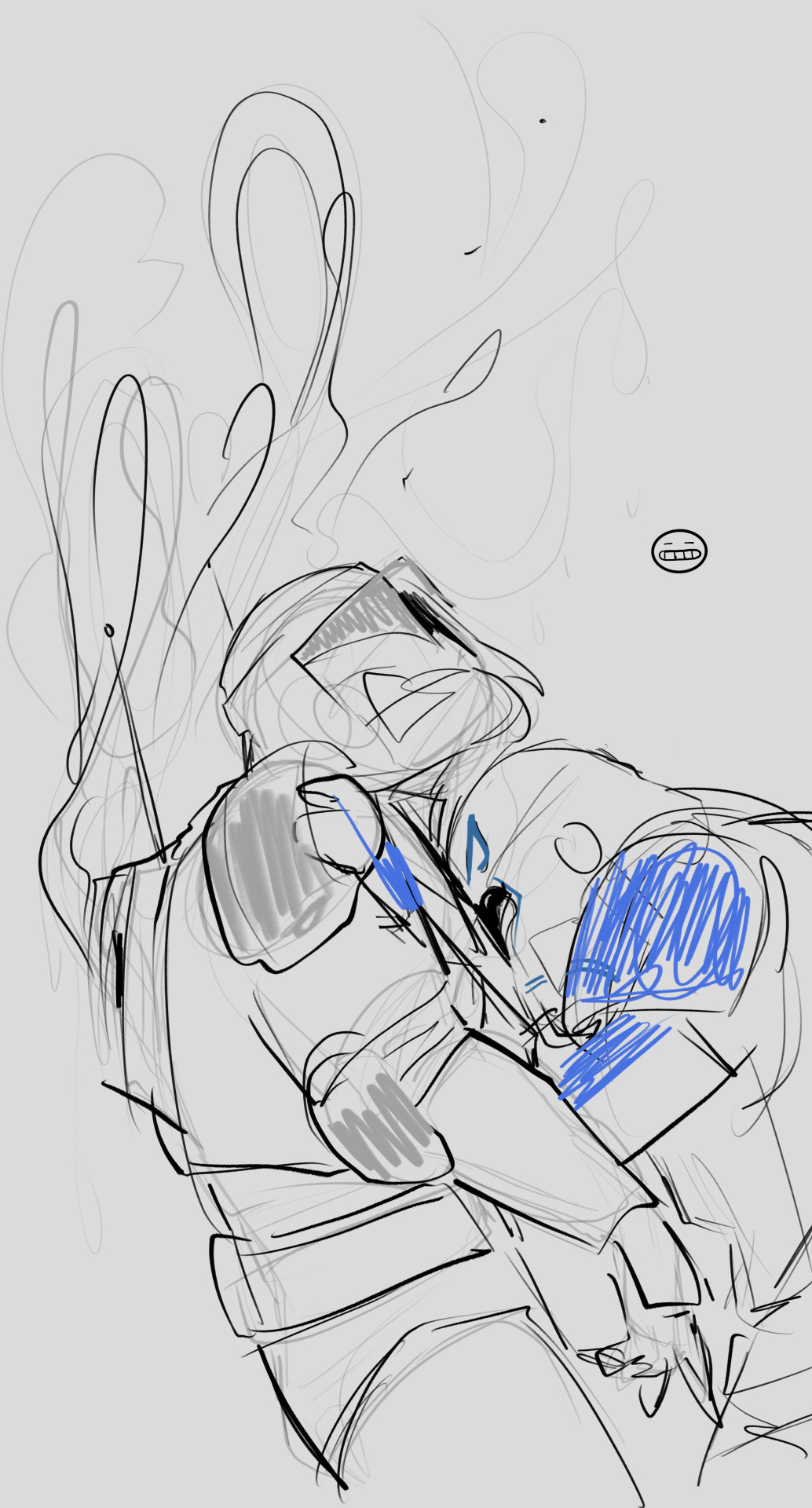

#*slaps scene* This baby can fit so much melodrama into it

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

GUT. PUNCHER. PLEASE. Ö

(also I see the Plo Coon WIP and I’m in the microwave)

In an instant CC-2224 sees the blue on the other clone and recognizes his enemy — knows it is CT-7567 and knows the name he took and the color of his hair.

All that is in him that is screaming — was (always?) screaming — quietens. His finger does not depress upon the trigger. His hand does not twitch towards the backup blaster on his hip.

An instant, a moment, a breath, and a single thought—

I’m no soldier.

CT-7567’s finger is as quick as he knew it would be. Between one moment and the next, Cody is free.

———

Re: Plo Coon — huehue, yess get microwaved (affectionate) (I’m very excited to show you)

#fan art#artists on tumblr#star wars: the clone wars#commander cody#captain rex#The opposite of a fix-it AU#wip tag game#OmPu Ask Hours#*slaps scene* This baby can fit so much melodrama into it#But also I do every now and then like to consider taking canon seriously in the rare points where it can bear the weight#And frankly if Cody does somehow throw off the effects of the chip IN CANON I will be frustrated because it will feel like retcon fanservic#CW: Major Character Death (implied)#CW: Guns#CW: Death#CW: Unhappy Ending (ish)#wip art

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

When A Bird Dies

Pair: Alcina/Mia

Summary: After Mother Miranda’s death, Alcina feels lost. She uses wine to cope and Mia tries to help her find a purpose.

AN: This one shot was inspired by Rosegarden Funeral Party’s Once In A While. It’s my first time writing Mia so apologies if it’s somewhat OOC. Ngl I was kind of just typing here and hoping for the best xD

Sometimes when she gets insecure, she gets drunk. And the lady is a woefully sloppy and unrefined drunk. Sometimes she drinks when she is sad. Mia doesn’t understand why she does this, the drinks only heighten her sorrow and leave her a sobbing mess.

On these nights, Mia wishes that she could carry the lady to bed. Lift her right off her feet and tuck her in. Perhaps rub her back until she comes back to herself. Her poised and fierce self. Back to the Alcina who speaks of skinning men alive and tasting their delectable blood.

But sometimes, the woman curled up and sobbing on the floor isn’t of any intrigue to Mia. She is a pitiful thing. And sometimes a disgusting sniveling thing. Really, Mia thinks that she ought to take the woman’s wine from her. Sometimes she grows tired of what it can reduce Dimitrescu to.

“You would do this in front of your daughters?” Mia asks.

“My daughters aren’t here.”

“Yes, they’re off fetching and bedding maidens.” She comments dryly. Sometimes bitterness gets the best of her. Sometimes she finds herself slipping and lapsing into something that she isn’t proud of, not even slightly. Maybe the woman in front of her is wearing off on her. Maybe it is this village infecting her just as swiftly as the mold.

“How dare you?” Lady Dimitrescu growls. She wipes her eyes, smearing mascara and foundation. Her face is twisted into a furious, almost feral snarl. Double so with crimson of blood-wine staining her teeth. “Talk about my daughters like that…” she slurs. “I’ve never said an ill word of that Rose.”

She could slap the woman. She very well should. Dimitrescu knows well that Rose is a subject not to be spoken of. Even years later it still stings to think of having to let the baby go. To think of having to let Ethan go. To have watched them make their way out of the village with only a glance back.

To know that the mold has infected and warped her so beyond repair that she had to let the two of them go and remain here amid the other freaks and monsters. And only this one, this sorry drunk had taken pity on her. Mia supposes that calling her a drunk is a bit of a stretch. She only drinks when she thinks. And lately she has been doing a lot of thinking. She says that she thinks until her head hurts. Undoubtedly she misses Mother Miranda, the wretched beast.

Without Mother Miranda she is both stronger and weaker. She is bolder, freer. Bolder, freer, and sadder. Though sometimes Mia thinks that it is merely a melodrama, that the mutant just wants attention. And with nothing better to do, Mia gives it to the woman. Most of the time she only dimly recalls having received any affection at all.

And maybe it is her maternal side that does the talking and moving. Her maternal side that compels her to help the tall lady to her unsteady feet. “You’re going to have to stop this.” Mia sighs. “You’re a lot stronger than this.”

.oOo.

Alcina shakes her head. These days she doesn’t feel much like that. Between Mother Miranda’s great fall and her own at the hands of Ethan Winters, she has found herself feeling rather inadequate.

Her weakness now runs so deep that she can’t even bring herself to go through with her vengeance. To drive a claw through one end of Mia and out the other and deliver the corpse straight to her husband and his wretched daughter.

Right now her head hurts too much to stand, let alone skewer a woman. And even if she had the ability she is coming to find that she has quite a soft spot for Mia. To think that she has fallen so low that she finds herself fancying a human. She is lucky that her daughters aren’t here to see this. She resents it with a fury, but Mia is right. She needs to get herself together.

“Sit with me?” She pats a spot on her lap. The woman hesitates. “Sit with me.” She still hesitates but climbs into her lap all the same. “You know that I was thinking of bleeding you out? I was going to chain you to the ceiling just the way I did your husband.” She pauses, trying to detect fear or hatred on the woman’s face. It remains blank. Impassive and unphased. “I was going to taste your blood on my tongue, surely it tastes better than your husband’s. Woman…” she leans closer, hovers her lips over Mia’s exposed neck. “Women taste better. Sweeter, richer. They aren’t so dirty and stale.”

“And how does your blood taste, Lady Dimitrescu?”

She furrows her brows, admittedly, the question has thrown her. “My blood…”

“I don’t bleed.”

“Everyone bleeds, Lady Dimitrescu.” Mia seems to study her face. “You just bleed differently. I imagine that your blood tastes like wine. You drink enough of it.”

Her face colors. It helps her case very little that she is already quite tipsy. Tipsy and absurdly emotional. She understands why Mia isn’t quite so intimidated by her today. “I do not bleed.” She repeats again.

“You would hemorrhage if your daughters died. Mother Miranda died and look at you...you’re bleeding all over the place.” She reaches up and wipes a tear from Alcina’s eye. “It’s depressing and fascinating to watch.” She pauses. “I’ve looked after a mutant before. Eveline. The infected definitely bleed. The hurt and cry just the way we do. You wouldn’t even know that some of them are mutated.”

Alcina cringes, “don’t you dare compare me to…”

“Humans?” Mia asks. “You were human once.”

“That...that was a very long time ago.” And there is not one part of her that wishes to return to that feeble, delicate state. “You’d do well not to bring it up again.” Where did she put the wine bottle? But the words have already well and settled upon her, she doesn’t think that more wine can drive them out this time.

Evidently she isn’t sure what to do. Isn’t sure that she has a purpose at all anymore. Donna has her dolls and Karl has his machines. She never thought that she would find herself near the same level as Salvatore--confused and lost.

She could continue to export her wines, she supposes. But that has lost its charm now that Mother Miranda won’t be around to stop in for a taste. To dully express a fondness for the drinks.

She has her girls but they have their own lives to live and now that the weather is warming, they are out and about more often.

“What shall I do, Mia?” She murmurs.

Mia’s face softens and the woman brings a hand to her cheek. Her hand is somewhat cold but the gesture has a warmth to make up for it. “About what? Your startling bloodlust?”

“What shall I do now that Mother Miranda is gone?”

“First you can put down the bottle.” She takes it right from Alcina’s hands and puts it aside. “And then you can start living your own life again. Your way.”

She isn’t sure that she remembers how.

“You used to enjoy jazz, yes?”

“Quite well.” She nods. And she still enjoys digging out an old record every now and then.

“Well, why don’t you put a record on, we can have dinner, and discuss how to get you back into the music industry.”

“I don’t believe that I fit into the scene anymore.” And she means it most literally.

“That’s what we’ll be talking about. I’d love to get out of this village every now and again. Perhaps you can do the singing and I can do some lip syncing?”

It isn’t such a horrid plan. If nothing else, it gives her something to fantasize about. Something to look forward to. And perhaps if she doesn’t kill the woman or corrode her soul completely--they might make a fine duo.

Mia casts a smile over her shoulder.

Sometimes, Alcina loses herself. At least this time she may have help finding herself.

18 notes

·

View notes