#(the creator is literally a friend of julie 'i was inspired to create legacies after the parkland shooting' plec)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

anyway the roswell new mexico show is also indescribably funny because i don't think anyone on this show is bilingual at all

#personal#they always have these moments where the hispanic characters mutter to themselves in spanish#but like extendedly and as if they forgot there aren't any people around#like these writers think if you're bilingual it's like Spicy tourette syndrome or smth#like that's not how being bilingual WORKS even if you're currently not speaking your first language#whenever i speak french i don't just randomly spout off in english every once and a while#i THINK in english but i stay speaking french#the most is that you might switch out sentences when speaking to someone with similar language capabilities#like you start a conversation in one language but then eventually you say a sentence in another and then continue on in that way#also they appear to have demanded that everyone who is meant to be hispanic be as obvious with it as possible#(like there's a character named 'rosa' and all the hispanic character do a hard rolling of the r in her name)#(even when speaking in unaccented american english and it is SO jarring)#(but what does one expect from a show that definitely started because the creators got socially conscious about latin american issues)#(for the first time in their entire lives and decided to spin a show around it)#(the creator is literally a friend of julie 'i was inspired to create legacies after the parkland shooting' plec)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Rise & Fall of Joss Whedon; the Myth of the Hollywood Feminist Hero

By Kelly Faircloth

“I hate ‘feminist.’ Is this a good time to bring that up?” Joss Whedon asked. He paused knowingly, waiting for the laughs he knew would come at the creator of Buffy the Vampire Slayer making such a statement.

It was 2013, and Whedon was onstage at a fundraiser for Equality Now, a human rights organization dedicated to legal equality for women. Though Buffy had been off the air for more than a decade, its legacy still loomed large; Whedon was widely respected as a man with a predilection for making science fiction with strong women for protagonists. Whedon went on to outline why, precisely, he hated the term: “You can’t be born an ‘ist,’” he argued, therefore, “‘feminist’ includes the idea that believing men and women to be equal, believing all people to be people, is not a natural state, that we don’t emerge assuming that everybody in the human race is a human, that the idea of equality is just an idea that’s imposed on us.”

The speech was widely praised and helped cement his pop-cultural reputation as a feminist, in an era that was very keen on celebrity feminists. But it was also, in retrospect, perhaps the high water mark for Whedon’s ability to claim the title, and now, almost a decade later, that reputation is finally in tatters, prompting a reevaluation of not just Whedon’s work, but the narrative he sold about himself.

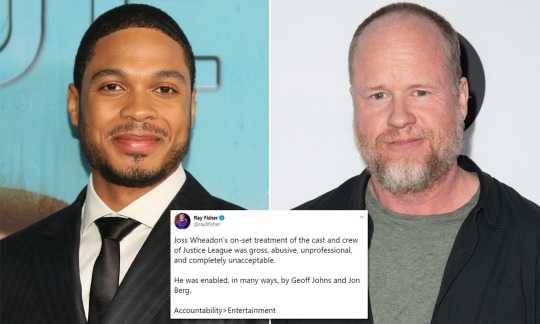

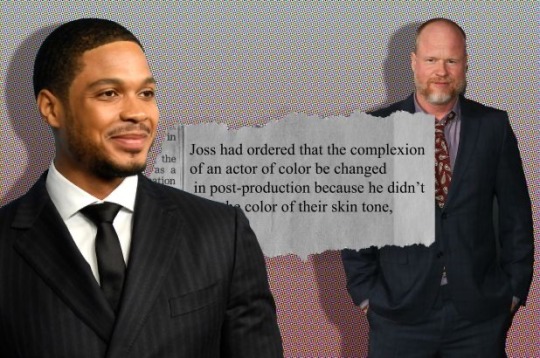

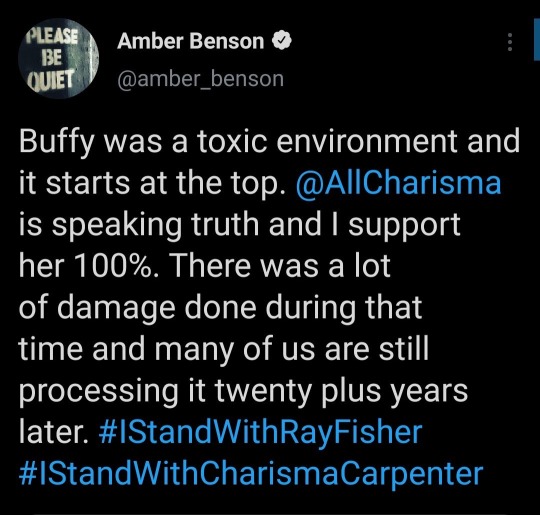

In July 2020, actor Ray Fisher accused Whedon of being “gross, abusive, unprofessional, and completely unacceptable” on the Justice League set when Whedon took over for Zach Synder as director to finish the project. Charisma Carpenter then described her own experiences with Whedon in a long post to Twitter, hashtagged #IStandWithRayFisher.

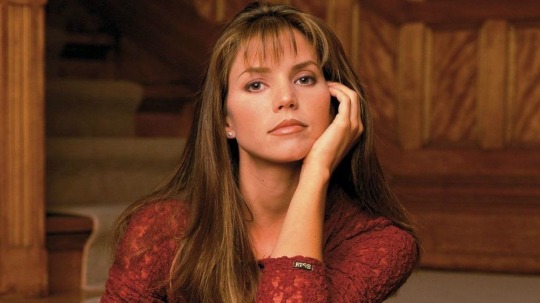

On Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel, Carpenter played Cordelia, a popular character who morphed from snob to hero—one of those strong female characters that made Whedon’s feminist reputation—before being unceremoniously written off the show in a plot that saw her thrust into a coma after getting pregnant with a demon. For years, fans have suspected that her disappearance was related to her real-life pregnancy. In her statement, Carpenter appeared to confirm the rumors. “Joss Whedon abused his power on numerous occasions while working on the sets of ‘Buffy the Vampire Slayer’ and ‘Angel,’” she wrote, describing Fisher’s firing as the last straw that inspired her to go public.

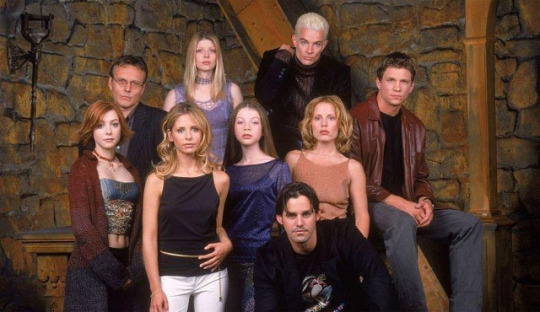

Buffy was a landmark of late 1990s popular culture, beloved by many a burgeoning feminist, grad student, gender studies professor, and television critic for the heroine at the heart of the show, the beautiful blonde girl who balanced monster-killing with high school homework alongside ancillary characters like the shy, geeky Willow. Buffy was very nearly one of a kind, an icon of her era who spawned a generation of leather-pants-wearing urban fantasy badasses and women action heroes.

Buffy was so beloved, in fact, that she earned Whedon a similarly privileged place in fans’ hearts and a broader reputation as a man who championed empowered women characters. In the desert of late ’90s and early 2000s popular culture, Whedon was heralded as that rarest of birds—the feminist Hollywood man. For many, he was an example of what more equitable storytelling might look like, a model for how to create compelling women protagonists who were also very, very fun to watch. But Carpenter’s accusations appear to have finally imploded that particular bit of branding, revealing a different reality behind the scenes and prompting a reevaluation of the entire arc of Whedon’s career: who he was and what he was selling all along.

Buffy the Vampire Slayer premiered March 1997, midseason, on The WB, a two-year-old network targeting teens with shows like 7th Heaven. Its beginnings were not necessarily auspicious; it was a reboot of a not-particularly-blockbuster 1992 movie written by third-generation screenwriter Joss Whedon. (His grandfather wrote for The Donna Reed Show; his father wrote for Golden Girls.) The show followed the trials of a stereotypical teenage California girl who moved to a new town and a new school after her parents’ divorce—only, in a deliberate inversion of horror tropes, the entire town sat on top of the entrance to Hell and hence was overrun with demons. Buffy was a slayer, a young woman with the power and immense responsibility to fight them. After the movie turned out very differently than Whedon had originally envisioned, the show was a chance for a do-over, more of a Valley girl comedy than serious horror.

It was layered, it was campy, it was ironic and self-aware. It looked like it belonged on the WB rather than one of the bigger broadcast networks, unlike the slickly produced prestige TV that would follow a few years later. Buffy didn’t fixate on the gory glory of killing vampires—really, the monsters were metaphors for the entire experience of adolescence, in all its complicated misery. Almost immediately, a broad cross-section of viewers responded enthusiastically. Critics loved it, and it would be hugely influential on Whedon’s colleagues in television; many argue that it broke ground in terms of what you could do with a television show in terms of serialized storytelling, setting the stage for the modern TV era. Academics took it up, with the show attracting a tremendous amount of attention and discussion.

In 2002, the New York Times covered the first academic conference dedicated to the show. The organizer called Buffy “a tremendously rich text,” hence the flood of papers with titles like “Pain as Bright as Steel: The Monomyth and Light in ‘Buffy the Vampire Slayer,’” which only gathered speed as the years passed. And while it was never the highest-rated show on television, it attracted an ardent core of fans.

But what stood out the most was the show’s protagonist: a young woman who stereotypically would have been a monster movie victim, with the script flipped: instead of screaming and swooning, she staked the vampires. This was deliberate, the core conceit of the concept, as Whedon said in many, many interviews. The helpless horror movie girl killed in the dark alley instead walks out victorious. He told Time in 1997 that the concept was born from the thought, “I would love to see a movie in which a blond wanders into a dark alley, takes care of herself and deploys her powers.” In Whedon’s framing, it was particularly important that it was a woman who walked out of that alley. He told another publication in 2002 that “the very first mission statement of the show” was “the joy of female power: having it, using it, sharing it.”

In 2021, when seemingly every new streaming property with a woman as its central character makes some half-baked claim to feminism, it’s easy to forget just how much Buffy stood out among its against its contemporaries. Action movies—with exceptions like Alien’s Ripley and Terminator 2's Sarah Conner—were ruled by hulking tough guys with macho swagger. When women appeared on screen opposite vampires, their primary job was to expose long, lovely, vulnerable necks. Stories and characters that bucked these larger currents inspired intense devotion, from Angela Chase of My So-Called Life to Dana Scully of The X-Files.

The broader landscape, too, was dismal. It was the conflicted era of girl power, a concept that sprang up in the wake of the successes of the second-wave feminist movement and the backlash that followed. Young women were constantly exposed to you-can-do-it messaging that juxtaposed uneasily with the reality of the world around them. This was the era of shitty, sexist jokes about every woman who came into Bill Clinton’s orbit and the leering response to the arrival of Britney Spears; Rush Limbaugh was a fairly mainstream figure.

At one point, Buffy competed against Ally McBeal, a show that dedicated an entire episode to a dancing computer-generated baby following around its lawyer main character, her biological clock made zanily literal. Consider this line from a New York Times review of the Buffy’s 1997 premiere: “Given to hot pants and boots that should guarantee the close attention of Humbert Humberts all over America, Buffy is just your average teen-ager, poutily obsessed with clothes and boys.”

Against that background, Buffy was a landmark. Besides the simple fact of its woman protagonist, there were unique plots, like the coming-out story for her friend Willow. An ambivalent 1999 piece in Bitch magazine, even as it explored the show’s tank-top heavy marketing, ultimately concluded, “In the end, it’s precisely this contextual conflict that sets Buffy apart from the rest and makes her an appealing icon. Frustrating as her contradictions may be, annoying as her babe quotient may be, Buffy still offers up a prime-time heroine like no other.”

A 2016 Atlantic piece, adapted from a book excerpt, makes the case that Buffy is perhaps best understood as an icon of third-wave feminism: “In its examination of individual and collective empowerment, its ambiguous politics of racial representation and its willing embrace of contradiction, Buffy is a quintessentially third-wave cultural production.” The show was vested with all the era’s longing for something better than what was available, something different, a champion for a conflicted “post-feminist” era—even if she was an imperfect or somewhat incongruous vessel. It wasn’t just Sunnydale that needed a chosen Slayer, it was an entire generation of women. That fact became intricately intertwined with Whedon himself.

Seemingly every interview involved a discussion of his fondness for stories about strong women. “I’ve always found strong women interesting, because they are not overly represented in the cinema,” he told New York for a 1997 piece that notes he studied both film and “gender and feminist issues” at Wesleyan; “I seem to be the guy for strong action women,’’ he told the New York Times in 1997 with an aw-shucks sort of shrug. ‘’A lot of writers are just terrible when it comes to writing female characters. They forget that they are people.’’ He often cited the influence of his strong, “hardcore feminist” mother, and even suggested that his protagonists served feminist ends in and of themselves: “If I can make teenage boys comfortable with a girl who takes charge of a situation without their knowing that’s what’s happening, it’s better than sitting down and selling them on feminism,” he told Time in 1997.

When he was honored by the organization Equality Now in 2006 for his “outstanding contribution to equality in film and television,” Whedon made his speech an extended riff on the fact that people just kept asking him about it, concluding with the ultimate answer: “Because you’re still asking me that question.” He presented strong women as a simple no-brainer, and he was seemingly always happy to say so, at a time when the entertainment business still seemed ruled by unapologetic misogynists. The internet of the mid-2010s only intensified Whedon’s anointment as a prototypical Hollywood ally, with reporters asking him things like how men could best support the feminist movement.

Whedon’s response: “A guy who goes around saying ‘I’m a feminist’ usually has an agenda that is not feminist. A guy who behaves like one, who actually becomes involved in the movement, generally speaking, you can trust that. And it doesn’t just apply to the action that is activist. It applies to the way they treat the women they work with and they live with and they see on the street.” This remark takes on a great deal of irony in light of Carpenter’s statement.

In recent years, Whedon’s reputation as an ally began to wane. Partly, it was because of the work itself, which revealed more and more cracks as Buffy receded in the rearview mirror. Maybe it all started to sour with Dollhouse, a TV show that imagined Eliza Dushku as a young woman rented out to the rich and powerful, her mind wiped after every assignment, a concept that sat poorly with fans. (Though Whedon, while he was publicly unhappy with how the show had turned out after much push-and-pull with the corporate bosses at Fox, still argued the conceit was “the most pure feminist and empowering statement I’d ever made—somebody building themselves from nothing,” in a 2012 interview with Wired.)

After years of loud disappointment with the TV bosses at Fox on Firefly and Dollhouse, Whedon moved into big-budget Hollywood blockbusters. He helped birth the Marvel-dominated era of movies with his work as director of The Avengers. But his second Avengers movie, Age of Ultron, was heavily criticized for a moment in which Black Widow laid out her personal reproductive history for the Hulk, suggesting her sterilization somehow made her a “monster.” In June 2017, his un-filmed script for a Wonder Woman adaptation leaked, to widespread mockery. The script’s introduction of Diana was almost leering: “To say she is beautiful is almost to miss the point. She is elemental, as natural and wild as the luminous flora surrounding. Her dark hair waterfalls to her shoulders in soft arcs and curls. Her body is curvaceous, but taut as a drawn bow.”

But Whedon’s real fall from grace began in 2017, right before MeToo spurred a cultural reckoning. His ex-wife, Kai Cole, published a piece in The Wrap accusing him of cheating off and on throughout their relationship and calling him a hypocrite:

“Despite understanding, on some level, that what he was doing was wrong, he never conceded the hypocrisy of being out in the world preaching feminist ideals, while at the same time, taking away my right to make choices for my life and my body based on the truth. He deceived me for 15 years, so he could have everything he wanted. I believed, everyone believed, that he was one of the good guys, committed to fighting for women’s rights, committed to our marriage, and to the women he worked with. But I now see how he used his relationship with me as a shield, both during and after our marriage, so no one would question his relationships with other women or scrutinize his writing as anything other than feminist.”

But his reputation was just too strong; the accusation that he didn’t practice what he preached didn’t quite stick. A spokesperson for Whedon told the Wrap: “While this account includes inaccuracies and misrepresentations which can be harmful to their family, Joss is not commenting, out of concern for his children and out of respect for his ex-wife. Many minimized the essay on the basis that adultery doesn’t necessarily make you a bad feminist or erase a legacy. Whedon similarly seemed to shrug off Ray Fisher’s accusations of creating a toxic workplace; instead, Warner Media fired Fisher.

But Carpenter’s statement—which struck right at the heart of his Buffy-based legacy for progressivism—may finally change things. Even at the time, the plotline in which Charisma Carpenter was written off Angel—carrying a demon child that turned her into “Evil Cordelia,” ending the season in a coma, and quite simply never reappearing—was unpopular. Asked about what had happened in a 2009 panel at DragonCon, she said that “my relationship with Joss became strained,” continuing: “We all go through our stuff in general [behind the scenes], and I was going through my stuff, and then I became pregnant. And I guess in his mind, he had a different way of seeing the season go… in the fourth season.”

“I think Joss was, honestly, mad. I think he was mad at me and I say that in a loving way, which is—it’s a very complicated dynamic working for somebody for so many years, and expectations, and also being on a show for eight years, you gotta live your life. And sometimes living your life gets in the way of maybe the creator’s vision for the future. And that becomes conflict, and that was my experience.”

In her statement on Twitter, Carpenter alleged that after Whedon was informed of her pregnancy, he called her into a closed-door meeting and “asked me if I was ‘going to keep it,’ and manipulatively weaponized my womanhood and faith against me.” She added that “he proceeded to attack my character, mock my religious beliefs, accuse me of sabotaging the show, and then unceremoniously fired me following the season once I gave birth.” Carpenter said that he called her fat while she was four months pregnant and scheduled her to work at 1 a.m. while six months pregnant after her doctor had recommended shortening her hours, a move she describes as retaliatory. What Carpenter describes, in other words, is an absolutely textbook case of pregnancy discrimination in the workplace, the type of bullshit the feminist movement exists to fight—at the hands of the man who was for years lauded as a Hollywood feminist for his work on Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel.

Many of Carpenter’s colleagues from Buffy and Angel spoke out in support, including Buffy herself, Sarah Michelle Gellar. “While I am proud to have my name associated with Buffy Summers, I don’t want to be forever associated with the name Joss Whedon,” she said in a statement. Just shy of a decade after that 2013 speech, many of the cast members on the show that put him on that stage are cutting ties.

Whedon garnered a reputation as pop culture’s ultimate feminist man because Buffy did stand out so much, an oasis in a wasteland. But in 2021, the idea of a lone man being responsible for creating women’s stories—one who told the New York Times, “I seem to be the guy for strong action women”—seems like a relic. It’s depressing to consider how many years Hollywood’s first instinct for “strong action women” wasn’t a woman, and to think about what other people could have done with those resources. When Wonder Woman finally reached the screen, to great acclaim, it was with a woman as director.

Besides, Whedon didn’t make Buffy all by himself—many, many women contributed, from the actresses to the writers to the stunt workers, and his reputation grew so large it eclipsed their part in the show’s creation. Even as he preached feminism, Whedon benefitted from one of the oldest, most sexist stereotypes: the man who’s a benevolent, creative genius. And Buffy, too, overshadowed all the other contributors who redefined who could be a hero on television and in speculative fiction, from individual actors like Gillian Anderson to the determined, creative women who wrote science fiction and fantasy over the last several decades to—perhaps most of all—the fans who craved different, better stories. Buffy helped change what you could put on TV, but it didn’t create the desire to see a character like her. It was that desire, as much as Whedon himself, that gave Buffy the Vampire Slayer her power.

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

Michelle Cadore

Michelle Cadore is the Designer, CEO, and visionary behind YES I AM, Inc, which she established in 2016. From an early age, Michelle has always been passionately involved in entrepreneurship and inspiring others.

As a graduate of the Zicklin School of Business with a degree in Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management, Michelle has built a career around helping others realize their personal, professional, and entrepreneurial goals. She spent three years in Public Administration as a Small Business Program Manager where she helped entrepreneurs expand their workforce. She now serves as an Assistant Director with the longest standing community-based organization in Brooklyn helping NYC residents to dream and do. A true renaissance woman, Michelle is also the Co-Owner and Managing Partner of a unique fashion boutique in the heart of DUMBO called DA SPOT NYC that houses 25+ independent minority owned fashion and creative brands. When Michelle is not grinding 24/7, she is spending time with family, traveling abroad and helping other small businesses.

Michelle is a big advocate for speaking positive words into your life and manifesting your goals into existence. She encourages others to stay inspired with the tagline “Brand Your Self.” Through YES I AM, Michelle plans to continue building a platform for others to be encouraged, share their own stories of triumph and own it! We spoke to Michelle about her work and being a creative.

Black Girls Create: What do you create?

I create inspirational and empowerment t-shirts. My brand is called YES I AM Clothing. I try to stick to positive messages that will keep people lifted. One of my sayings is “But, she didn’t quit though,” which I started using I try to figure out the next moves in my career and for my business. It’s really to keep myself motivated as well as others.

I’m also building a network. I have a shop called DaSpot NYC where I house 32 minority-owned brands including my own. Our goal is to connect independent and local minority-owned brands with the public, giving them that platform, and also to build a bigger network of creatives and professionals to further build Black power, money, everything.

BGC: What made you get into apparel and creating your own brand?

I was actually working for the Department of Small Business Services as a Program Manager, giving funding to small businesses. I was going for a promotion, but when I got up the nerve to ask for the promotion, I was told “we’ll see who else is interested.” That was like a slap in the face for me, because I’d been doing this job for about two years, pretty much doing the role for which I was trying to interview for free. I realized then that I needed to create my own opportunities.

That night I went home, feeling a little down. It was raining and I was standing on the corner, and a cab came by and splashed me from head to toe. I took that as a sign from the universe that I needed to get my stuff together. I reminded myself that I’d done amazing things before and that I would continue to do amazing things after. I am who I say I am.

That was when I realized I wanted to create a brand called YES I AM, to create clothing to inspire people. And that’s exactly what I did. I went home that night and I went to work, and the brand was born. That was November 16, 2015.

"I appreciate the “no,” it keeps you going." -- Michelle Cadore

I officially launched on July 17, 2016 after getting prepared, getting a mentor to guide me. Having YES I AM afforded me enough to open DaSpot. Having my business and having my mentor — who eventually became my business partner — took me down the journey I think God meant for me. Sometimes you need to have that push and be in the place of discomfort. I find we grow when we’re not comfortable. We have to challenge ourselves. So I always look back at that job that said “no” and I say “thank you.” I appreciate the “no,” it keeps you going.

BGC: What has been one of the top learning moments in starting your own business?

I think the top learning moment for me was to do your due diligence, which I tend to do very well. Also don’t respond to negativity. I had this very interesting situation where I was accused of ripping off someone’s design. I had no idea these people even existed — they were all part of the same circle of Black entrepreneurs. My name and brand ended up being dragged all through the internet streets. Rather than come to me professional to professional, business woman to business woman, Black person to Black person, it was just drag. I got a cease and desist the day I started my new job, with an ask for $10,000.

I wanted to so defend my name, but my partner was like don’t even answer, let your lawyer handle it. So that’s exactly what I did. After my lawyer looked at the papers, he asked me, “do you want a T-shirt, or do you want a brand?” And it really reminded me to focus on what’s important. Four months later he stumbled across the [location for our] shop and we opened up our second business.

So my lesson is basically to always give people the benefit of the doubt in business. Handle things professionally. And at the same time, there are certain things you don’t need to respond to. It’s better to not fuel and give in to certain things, to keep your eyes focused and make sure you have a good team around you who can guide you so that you’re making the right decisions and not getting messy in the streets. That was my biggest lesson, having to humble yourself not to say anything when you really want to say something because it’s not even important.

BGC: Who is your audience?

My audience really started off as everybody, but I’ve noticed that as the years pass my core audience is mostly women of color. It’s expanding, but basically anyone who is seeking or identifies with the messages, who look for inspiration and motivation, they’re drawn to the brand. I just focus on delivering the message. But I definitely say women are the majority. We are the biggest buyers, so it’s no surprise.

BGC: Who or what inspires you to keep going?

My mom is part of my inspiration because she was a nurse for 40 years (she’s retired) and she has been a business woman on the side even through having her own career. I’ve seen her do a lot of businesses and when it might not work out she’ll try something else. I know that she really wants to see us continue with that legacy, generational wealth building, just having our own. So I’m super proud to have built something and to say that I’ve seen my mom start her own businesses like I started my own business that I’ve managed to keep going. I’m doing what she’s been wanting to do, finding that thing that works. She’s my biggest inspiration because I know that she knows I’ll be okay. I can find my way.

BGC: Why is it important as a Black person to create?

God bless the child that’s got his own. We are inherently entrepreneurs, from times when we didn’t have a choice because they didn’t want us in their schools, their banks. We had to build our own. I’m all about Black wealth and building our economy, being financially strong, and also creating that legacy. I want to leave a legacy and build generational wealth for my family. We have to keep building and remember who we are and keep it going.

BGC: How do you balance creating with the rest of your life?

I have no idea. For the last two years I have literally run between a full time job — I’m an Assistant Director during the day, managing two teams — and then going to the shop and creating sometimes until 3am. And then I take care of my mom, and I have my personal life. It’s been a lot. I realized in the last two years that every time it comes to December, my body would crash. So this year I’ve made a vow to myself to put self care at the top of the list and make sure that I take pride in my appearance, in taking care of myself. I schedule in time to do the things that are important to me. I actually created a list for the summertime of like 35-40 things I want to do this summer, which includes everything from rock climbing and kayaking on the East River to hanging out with friends, having picnics, or whatever. And I’ve been crossing things off. And I’m dating, so I’m trying to schedule time and really balance. I’m actually super happy I’m at this point. This has by far been the best summer, the best year compared to the last two.

It can be really hard to take time for yourself. For one, I’m usually on autopilot. And for another, sometimes I think that if I focus on that, I’m taking away from my business, I’m not putting my all in. But I find that you can put your all in and then you’re dead, you’re gone. You’re not as rich if you’re not building those relationships around you and you’re not feeding the things that nurture you. If your business is gone tomorrow, what do you have left? It’s important to live a full life. I’m trying as best as I can little by little.

BGC: Any advice for young and new creators?

Fail. Fail and fail often. Get a mentor, because then you have someone to help guide you. But when you’re early on in the process, it’s better to learn the hard lessons then, rather than when you get bigger and your business is booming because it will probably be more costly. Don’t be afraid to do whatever it is you want to do. If it doesn’t work out, it’s okay, you find another way to do it. You have to be okay with trying and failing.

"Be bold enough and ready to jump and do it. Better to live passionately than not live at all. " -- Michelle Cadore

You also have to be okay with success. Everybody wants to be successful, but they’re afraid of when they actually have a level of success. Some people are afraid of jumping, they want it but they don’t want to jump. And I’m here to say do it. That was my biggest fear when I started, ironically. It was like what if people don’t like it. I had a mentor who pushed me. And when I made my first shirt and first sale, I was like “oh my god they like it, this works.” So I look back now like what the hell was I afraid of? I can’t even imagine not starting another business just out of fear. Be bold enough and ready to jump and do it. Better to live passionately than not live at all.

BGC: If you had unlimited resources, what is something you would love to do?

I’m already writing it down, trying to manifest like millions of dollars. I definitely would love to see YES I AM as a store in different locations. And beyond just being clothing, the brand is inspiration. So I want it to be on that level where the person would go to YES I AM just for that dose of daily inspiration.

For DaSpot, we have the boutique side and we have a production space now as of February. We now print for brands and businesses, and we also give artists and brands space to showcase their work. So ideally I would love to have DaSpotNYC, Atlanta, London, Paris, South Africa, just going to different markets and really working with independent artists in those places. If I had the people and the money to really make it big, that would be the goal. And of course you have a social responsibility of giving back, teaching entrepreneurs how to grow their businesses. Some consulting and building creatives. We just need the money.

BGC: Future projects?

I have a few things brewing for the summer. Mainly we have festivals, so I’ll be at We Of Color at WeWork for their Juneteenth event, doing Pride fests, and Airbnb has us for another festival as well. I’m also launching a consultancy business for people trying to grow their businesses. I’ve been doing it for years so I’m giving myself until the end of the month to have everything completed and finalized so that I can really start taking that leg of business to the next level. And I’m writing a book called Nathan Does South Africa, which is loosely based on my experiences on a trip for my 31st birthday where I traveled through South Africa solo. It’s basically a little boy, Nathan (named after my nephew), who is about 6 years old and traveling for the first time. It’s important for minority kids to get comfortable and familiar with traveling and being exposed to different countries and customs. He’s someone who looks like them. So I’m excited about that.

You can find YES I AM, Inc. and DaSpot NYC online, but also in Dumbo, Brooklyn!

0 notes