#茶ナル

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

2024/8/10

音家atお茶の水NARU

#canon#キヤノン#canon photos#canon powershot g7 x mark ⅲ#powershot g7 x mark ⅲ#音家#otoie#お茶の水ナル#お茶の水NARU#tomonao hara#yuki oka#hatsune hirakura#riku takahashi#toyoaki sekine#原朋直#岡勇希#平倉初音#高橋陸#関根豊明

0 notes

Text

2024/2/16 Otoie at NARU

2/16(金) お茶の水 ナル "音家"

Open18:00 Start19:00 Music charge¥3,500+order

原朋直/tp, 岡勇希/sax, 平倉初音/p, 高橋陸/b, 関根豊明/ds

NARU 03-3291-2321, http://ocha-naru.com

#jazz#ジャズ#tomonao hara#原朋直#trumpet#music#トランペット#音楽#音家#平倉初音#hatsune hirakura#yuki oka#riku takahashi#岡勇希#高橋陸#関根豊明#toyoaki sekine#ochanomizu naru#naru#お茶の水ナル#otoie

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

【顔出し】〇〇〇フェイスに艶々お肌のTHE癒し系清楚。敏感なカラダは可愛い顔が崩れる程に感じまくる!は怒られちゃうからたっぷり腹出し&お掃除F - 無料動画付き(サンプル動画)

【顔出し】〇〇〇フェイスに艶々お肌のTHE癒し系清楚。敏感なカラダは可愛い顔が崩れる程に感じまくる!は怒られちゃうからたっぷり腹出し&お掃除F - 無料動画付き(サンプル動画) スタジオ: FC2 更新日: 2024/12/15 時間: 61分 女優: こんにちは 男優の『成せばナル』です 実は前回、約束外のをかまして彼女を怒らせてしまいました。 とても性格が良さそうなこだったけど、それとはこれとは話が違う様です。当たり前ですよね、、、 私が勝手にをした訳じゃなく、師匠の指示でした。 怒ってしまいシャワーを浴びてる彼女に 『なだめて、もう一度撮影させろ』と言われ駆り出されました。 正直、無茶苦茶すぎです、、、しんどかったです。 そしてなんとか理由を説明して許せてもらえたんです。。。 階段を登りながらフェラをさせたりと、面白い事をして機嫌を取りました。 【DVDハッピー】 https://dvd-happy.com/ ストリーミング・ダウンロード・DVD $1.49~ 正規品最安値保障 ***********************************

0 notes

Text

【顔出し】〇〇〇フェイスに艶々お肌のTHE癒し系清楚。敏感なカラダは可愛い顔が崩れる程に感じまくる!は怒られちゃうからたっぷり腹出し&お掃除F - 無料動画付き(サンプル動画)

【顔出し】〇〇〇フェイスに艶々お肌のTHE癒し系清楚。敏感なカラダは可愛い顔が崩れる程に感じまくる!は怒られちゃうからたっぷり腹出し&お掃除F - 無料動画付き(サンプル動画) スタジオ: FC2 更新日: 2024/12/15 時間: 61分 女優: こんにちは 男優の『成せばナル』です 実は前回、約束外のをかまして彼女を怒らせてしまいました。 とても性格が良さそうなこだったけど、それとはこれとは話が違う様です。当たり前ですよね、、、 私が勝手にをした訳じゃなく、師匠の指示でした。 怒ってしまいシャワーを浴びてる彼女に 『なだめて、もう一度撮影させろ』と言われ駆り出されました。 正直、無茶苦茶すぎです、、、しんどかったです。 そしてなんとか理由を説明して許せてもらえたんです。。。 階段を登りながらフェラをさせたりと、面白い事をして機嫌を取りました。 【DVD村】 https://uradvd-mura.com/ ストリーミング・ダウンロード・DVD 大手メーカーから個人撮影まで $1.49~ ***********************************

0 notes

Text

【顔出し】〇〇〇フェイスに艶々お肌のTHE癒し系清楚。敏感なカラダは可愛い顔が崩れる程に感じまくる!は怒られちゃうからたっぷり腹出し&お掃除F - 無料動画付き(サンプル動画)

【顔出し】〇〇〇フェイスに艶々お肌のTHE癒し系清楚。敏感なカラダは可愛い顔が崩れる程に感じまくる!は怒られちゃうからたっぷり腹出し&お掃除F - 無料動画付き(サンプル動画) スタジオ: FC2 更新日: 2024/12/15 時間: 61分 女優: こんにちは 男優の『成せばナル』です 実は前回、約束外のをかまして彼女を怒らせてしまいました。 とても性格が良さそうなこだったけど、それとはこれとは話が違う様です。当たり前ですよね、、、 私が勝手にをした訳じゃなく、師匠の指示でした。 怒ってしまいシャワーを浴びてる彼女に 『なだめて、もう一度撮影させろ』と言われ駆り出されました。 正直、無茶苦茶すぎです、、、しんどかったです。 そしてなんとか理由を説明して許せてもらえたんです。。。 階段を登りながらフェラをさせたりと、面白い事をして機嫌を取りました。 【DVDハッピー】 https://dvd-happy.com/ ストリーミング・ダウンロード・DVD $1.49~ 正規品最安値保障 ***********************************

1 note

·

View note

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (74b): Ten Poems that Nambō Sōkei Found on Rikyū’s Wastepaper (Part 2).

〽 Large is large, small is small. [And with respect to] the five kane, [irrespective of] whether [the object] is round or square, [it should be handled] according to the attributes it possesses¹.

〽 The kane are nothing but the Kogitsunemaru’s imaginary hammerman; refrain from hitting the blade [squarely] on its [sharp] edge, [but also] from missing the blade [entirely]².

_________________________

¹Dai ha dai shō ha shō naru itsutsu kane, maruki mo hō mo sonawari ni keri [大ハ大小ハ小ナル五ツカネ、圓キモ方モソナハリニケリ].

Dai ha dai shō ha shō naru [大は大小は小成る] means the large are large, the small are small.

Marui mo hō mo [丸いも方も] means whether it is round or square (rectangular)....

Sonawari ni keri [具わりにけり]: sonawari ni [具わりに] means according to the attributes that (the object) possesses; keri [けり] means to be settled.

In other words, the shape of the object is not important. The way it is handled depends on its size, since this is the determining attribute in so far as kane-wari is concerned.

If, for example, the object is small, so that it contacts only one kane, then it should be arranged on the daisu or other sort of tana, or directly on the mat, accordingly (taking care that it is oriented, relative to the kane with which it is supposed to be associated, appropriately); and if it is large (such as a kuguri-bon), so that it contacts multiple kane, then that (and the effect it produces on the kane-wari total) must be taken under consideration when placing it.

The diction of this poem is better compared with the poetic conventions of the late seventeenth century than to those found in any of the poems known to have been composed by Rikyū (such as in his additions to the Chanoyu hyaku-shu [茶湯百首] -- Hundred Poems -- and those that were included in his various densho [傳書]).

==============================================

Shibayama explains that “this poem is intended to focus our attention on the kane value of yin or yang [based on how many kane the object crosses].”

——————————————–———-————————————————

Tanaka writes, “kane-wari is not something that is only applicable to the subdivision of the tenjō [天井]* or the ji-ita [地板] of the daisu. [Rather,] the 1-ken toko, too, as well as the 2-ken toko, and also to the [shelves of] the 1-shaku 5- or 6-bu small tana†, the 9-sun or 1-shaku [wide] tsuri-dana, as well as to the round or rectangular trays that are placed on the daisu: in all of these settings, the rules of kane-wari can be applied perfectly.

“For this reason, when the 1-shaku 3-sun dai-maru-bon [大丸盆] is placed on the daisu, the tray naturally binds together the yin and yang of the five kane‡ [in such a way] that the tray becomes yang**; but when the 1-shaku 6-sun [shaku-naga]-bon [尺長盆] is placed [on the ten-ita of the daisu], because the yin[-kane] preponderate [among those over which the tray extends], the yin-yang plainly guide [the way things are done]††. It is for this reason that, when handling the various kinds of utensils, the rule of tsuzuki-kane is applied [in other words, the principal utensils are associated with successive yang kane].

“But on the other hand, when we display a suzuri and ken-byō, or fude-kake on a 1-ken [wide] tsukue-doko [机床]‡‡, the issue of continuance becomes more complicated***. When a scroll is hung up in a wide toko, the function of the yin and yang is [also] called into being; and the problem of whether [the kane] are bound together or not becomes an insoluble problem†††.

“Large is large, small is small -- and things are as they are. And so the problems [of this sort that we encounter] with the five kane are inevitable. In short, no matter where we are [in the shoin or the sō-an], or the size of the object, and irrespective of the wideness or narrowness [of the space where it will be displayed], there is no place that is exempt from the influence of the five kane -- this is what the poem says.

“The reason why five kane are specified here is because the five kane [system] includes the idea of yin and yang, while the seven kane [system] does not. As a result [in the latter setting] the problematic ideas engendered by the five-kane do not arise‡‡‡.” __________ *Tenjō [天井] (which means ceiling) or tenjō-ita [天井板], are other names for the ten-ita [天板] -- the upper shelf of the daisu.

†Tana of this sort, which were derived from the half of the fukuro-dana on which the mizusashi was displayed, are also referred to as mizusashi-dana [水指棚].

‡This use of “five-kane” to mean the eleven-kane is, of course, an attempt to fit Imai Sōkyū’s eleven kane into the terminology of the original five-kane system (where only the original five yang-kane -- which represented the folds and edges of the shiki-shi [敷き紙] -- were recognized and used as the basis for the arrangements).

**In other words, the tray is oriented in such a way that it covers more yang kane than yin, thereby (according to the logic employed by the author of this entry) making it yang. (Of course, if only the yang-kane were recognized, as was originally the case, necessarily trays that were arranged on the daisu would have been yang as a matter of course.)

††Again, this assertion goes against the classical teachings, introducing complications that were a hallmark of Imai Sōkyū’s approach to chanoyu (this is the aspect to which the modern secrets-based way of teaching chanoyu traces its origins).

‡‡The tsukue-doko [机床] is the built-in writing desk in the shoin room.

***In other words, this is alluding to the case where something like the ken-byō [硯屛] or fude-kake [筆架] joins the interstitial yin-kane to the neighboring yang-kane, so that the yin becomes an extension of the yang. (As explained in the previous post, this seemed logical because the separation between the yin and yang kane on the 1-ken wide tsukue-doko is the same as between the yang kane on the daisu -- in both settings the kane are approximately 5-sun apart. And so, for this reason, placing some of the writing implements on the yin kane looked appropriate, since the separation was identical to the separation between the utensils on the daisu.)

†††The proportions of the scroll were naturally based on the size of the painting or writing that was being mounted. The question of how many yin or yang kane the resulting scroll would cross was never a matter of consideration (indeed, because the principal hook from which the scroll is suspended is in the exact center of the wall, the scroll was naturally yang, regardless of how many yin or yang kane it ultimately crossed -- though, because of this line of theorizing that was articulated by Imai Sōkyū, the scroll could technically be rendered yin if it crosses more yin kane than yang, and this is the issue that is so perplexing to Tanaka Senshō).

‡‡‡If the yin were not added into the mix, then the difference would be not between whether the yin are considered or not, but between the nature of the setting: the five-kane system was based on the shiki-shi, while the seven-kane system was created in the absence of the shiki-shi (which could not be used in the inakama room: simply reducing the size of the shiki-shi would be meaningless, since the utensils would no longer retain the same sorts of relationships as in the original setting)

==============================================

²Kane ha tada Kogitsune-maru no mu-sō tsuchi, hoko ni na ate so hoko na ha zushi so [カネハ只小狐丸ノ夢想槌、ホコニナ當テソホコナハヅシソ].

Kogitsunemaru [小狐丸] was the name of a famous sword created by the semi-legendary late Heian period master swordsmith Sanjō Kokaji Munechika [三條小鍛冶宗近; dates unknown], the founder (shiso [始祖]) of the Sanjō-ha [三条派] (Sanjō School)* of swordsmithery. The name refers to the creation legend that accompanied the sword (I have translated this account from the Sanjyokokajimunechika.com website):

“One night, Emperor Ichijō [一條天皇; 980-1011] had a strange dream, and sent Michinari Tachibana as an imperial envoy to order Munechika, a renowned craftsman of the day working in Sanjō [south of the Imperial Palace compound], to strike a sword.

“Although Munechika accepted the commission, he felt he was unable to strike the sword by himself. But as he was troubled over the fact that none of his contemporaries were good at hammering [iron], he resolved to put his faith in the kami. So he went to his guardian deity, Inari myōjin [稲荷明神]†, to pray for assistance.

“In answer to his prayers, a magical boy appeared and, strangely enough, this child already knew about the imperial command. The child reassured him with the words ‘as you have been blessed [by Inari myōjin], the sword will certainly come to be made [successfully].’

“He then told [Munechika] stories about the great virtues of the famous [historical] swords, both domestic and foreign‡ -- and, in particular, he related the story of Yamato Takeru’s [日本武尊]** Kusanagi [草薙] sword in detail; and he said, ‘I will change the magical powers of my body into an ability, which I will pass over [to you],’ after which he disappeared into Mt. Inari.

“Munechika returned to his compound, set up his anvil surrounded by a shime-nawa [標���]††. And, as he prepared to hammer the sword according to the [magical] child’s instructions, he prayed; and while he paused, a fox-messenger from Inari myōjin appeared. And this divine messenger helped to strike the sword‡‡.

[The Kogitsunemaru sword (or possibly an Edo period copy), as it exists today.]

“Presently the sword was completed. It bore the inscription Kokaji Munechika [小鍛冶宗近] on the front side of the blade; and, on the back, Kogitsune [小狐]***.

“When the sword was presented to the Imperial Envoy, the fox-messenger returned to Mt. Inari.”

Musō-tsuchi [夢想槌] means imaginary hammer -- this is a reference to the fox-messenger who assisted Munechika to hammer the sword.

Kane ha tada Kogitsunemaru no musō-tsuchi [カネは只小狐丸の夢想槌] means that the kane are nothing but the magical assistants that help us to arrange the utensils correctly.

Hoko [鋒; also written 切っ先] means the edge of a blade (and can be understood as being equivalent to the kane in this poem).

Waka poems have two halves -- the kami-no-ku [上の句] (which consists of three lines of 5, 7, and 5 syllables), and the shimo-no-ku [下の句] (consisting of two lines of 7 syllables each). In this poem, the shimo-no-ku presents us with the two possible situations that demand our attention:

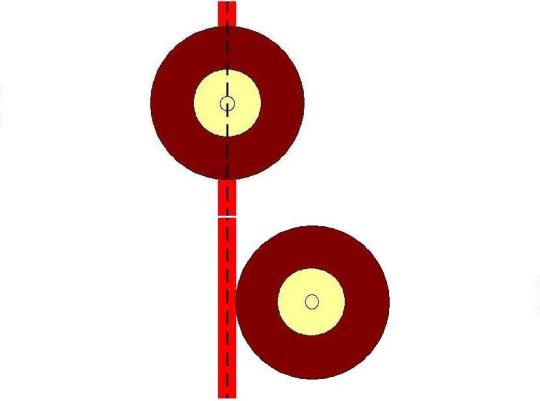

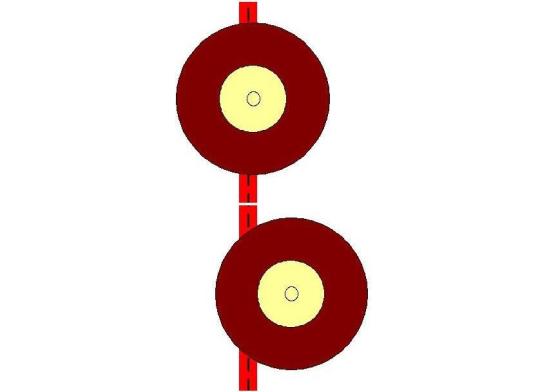

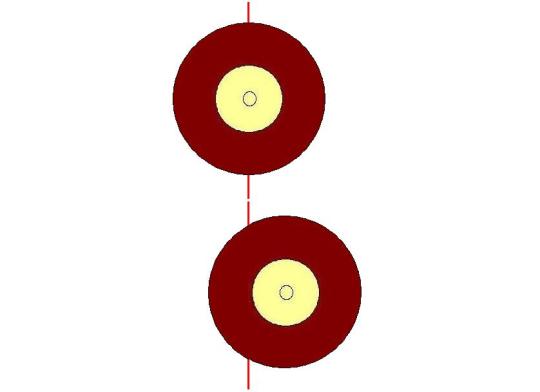

◦ hoko ni na ate so [鋒にな當てそ]††† means do not hit squarely on the edge of the blade -- this should be interpreted to mean “do not place the utensil so that its exact center aligns with the exact center of the kane” (this is the situation depicted in the upper sketch);

◦ hoko na hazushi so [鋒な外しそ] means do not miss the blade‡‡‡ -- again, this should be interpreted to mean that “the utensil should not be displaced fully from the kane with which it is supposed to be associated” (lower sketch).

In other words, this poem is discussing the way in which each utensil (not just the chaire) should be aligned with its kane when displayed on the daisu (or in some other place)**** -- placing it so that it is exactly centered on the kane, as well as obviously disassociating it from the kane, are both to be avoided.

Once again, this poem, which draws on the poetic conventions of the late seventeenth century (such as citing obscure historical references, and employing Edo period idiomatic usages), would have been highly aberrant for someone like Rikyū. ___________ *The forge he established continues to this day at a site in Nara.

†Inari myōjin [稲荷明神], also referred to as Inari-no-kami [稲荷神] (the name is also read Inari-jin) is a grain spirit and agricultural god, who symbolizes rice (this god is also considered synonymous with the god Uka-no-mitama [御食津神]; and, indeed, Uka-no-mitama is the deity who is usually enshrined in the Inari shrines, including in the Fushimi Inari taisha [伏見稲荷大社], which is generally regarded to be the principal Inari shrine in Japan). He is usually depicted as a humanoid fox-spirit, or an anthropomorphised god riding on the back of a magical fox.

Originally the god of grains and agriculture, he was later considered to be the god of all types of production, and so including commerce and industry within his purview. As a result, he is one of the most widely worshiped gods in Japan.

Inari-kami has also been conflated with the Buddhist goddess Dakini-ten [荼枳尼天] (Ḍākiṇī [डाकिनी], a type of female spirit, goddess, or demon in Hinduism and Buddhism, who often functions as a sort of sky-mother) in Shintō-Buddhist syncretism, so this entity is sometimes enshrined in Buddhist temples as well. As a result of the conflation with Inari-kami, representations of this deity usually partake of Inari’s fox imagery to a greater or lesser extent.

‡The expression used in the story is wa-kan [和漢]. Though generally interpreted in a narrow sense by the nationalist scholars of the early 20th century to mean Japan and China, historically this compound means (things) from Japan and (things) from the continent. Most “Chinese” things were imported (and interpreted) through Korea.

**Yamato Takeru no mikoto [倭建命; his dates of birth and death are unknown -- in later documents, usually those with a more nationalist bent, his name is often written 日本武尊命], was a son of the legendary twelfth Emperor of Japan. Takeru is said to have disguised himself as a maidservant so he was able to approach their chieftain (in order to stab him to death) in a successful plot to eliminate the leaders of the Kumaso [熊襲] tribe in Kumamoto [熊本] (in west-central Kyūshū, across the Ariake Sea from the island of Nagasaki -- though the Kumaso’s territory probably extended all the way to the southern tip of the island), in his efforts to bring the island of Kyūshū under his father’s sway.

The sword Kusanagi [草薙] was originally known as Ame-no-Murakumo-no-Tsurugi [天叢雲剣], which means “Heavenly Sword of the Gathering Clouds.” This is the sword that is part of the Imperial Regalia (and, according to the accounts of Western-trained Japanese scholars who examined this sword early in the previous century, it, like the mirror and the jewel, were all of Korean origin -- which is why it has been forbidden for the regalia to be exhibited since the early 20th century, rather than on account of its rather dubious “divinity”). This sword was originally preserved in the Ise shrine, and was given to Takeru by his aunt (who was serving as the high priestess of that shrine) so that he might use it to subdue a rebellion against the Imperial Court in the “eastern land” (which was not yet incorporated into the Japanese state).

††The Shintō rope made of rice-straw, from which white paper streamers depend, that defines or demarcates an area of ritual purity.

‡‡The act of hammering the iron into a blade, called ai-zuchi [相鎚], requires two smiths, who alternate their strikes. This was why Munechika had been so perplexed after receiving the commission from the Emperor Ichijō -- because, while Munechika was renowned for his skill, there was no one else skilled enough to handle the second hammer. Yet since there was no one else, he had to do it by himself by altering his rhythm -- imagining that each second stroke was coming from an imaginary, mystical hammerman.

***Kogitsune [小狐], which means Little Fox, was apparently an abbreviated form of the name of the divine fox-messenger (which would, in full, have been Kogitsunemaru [小狐丸] -- the kanji -maru [-丸] was commonly suffixed to child’s names).

†††The construction na...so [な...そ], where these two particles bracket a verb -- hoko ni na ate so [鋒にな當てそ] hoko na hazushi so [鋒な外しそ] -- means “don’t do (whatever the verb says).” Therefore, na ate so [な當てそ] means do not hit (the exact center of the kane), and na hazushi so [な外しそ] means do not displace (from the the kane).

‡‡‡The image is that of the second swordsmith, who alternates his strokes with the first. If he hits squarely on the sharpened edge of the blade, he will destroy it, while if his stroke hits the anvil, rather than the blade, it will all be in vain.

****There are several other possible interpretations of what this poem is suggesting that have been advanced by Nampō Roku scholars:

◦ Some commentators discuss this poem specifically as it relates to the concept of mine-zuri [峯摺り] (where the utensil is centered on its kane) versus san-bun-ichi kakari [三分一掛り] (where it overlaps its kane by one-third).

◦ Others, however, focus on the idea that even when the object should be fully aligned with its kane, to align it perfectly (so that the center of the object matches the exact center of the kane) is presumptuous. Therefore, these scholars assert, it is always better to be reticent -- the exact center of the object should be ever-so-slightly displaced from the true center of the kane.

To understand the origin of these ideas, we must remember that the three central kane on which objects are displayed on the daisu (and which derived from the folds of the shiki-shi) were originally 3-bu wide (the outer two were simple lines, corresponding to the edges of the shiki-shi). Thus, for the center of the object to be located anywhere within that strip would still mean it was fully aligned with its kane, while placing the edge of the object’s foot to the left or right of that strip would constitute san-bun-ichi kakari (overlapping the kane by one-third).

In the above sketches, the upper shows the chaire as it should be aligned with its kane (this is what is usually called mine-zuri in the Nampō Roku, meaning that the exact center of the utensil is displaced slightly from the center of the kane); while in the lower one it overlaps its kane by one-third (the foot touches the right edge of the kane without entering onto it).

Of course, once the kane were uniformly reduced to simple lines (when the edges of the temae-za were pulled inward, so that the temae-za would end at the inner edges of the heri, rather than in the middle of the heri), the question of ma-boko versus mine-zuri became much more subtle (aligning the center of the utensil so that it is immediately to the side of a Euclidean line would be virtually the same as placing it squarely on the line -- so this would be more of an idea or intention than a matter of brute fact, since it will not be obvious to the guests).

==============================================

Shibayama writes, “with respect to mine-zuri [峯摺り]*, one should avoid [hitting] the [cutting] edge of the blade [since doing so will dull it†]. Sensitivity is the secret when tempering a sword, so this is intended to teach us [the importance of] evocation.” ___________ *Mine-zuri [峯摺り] literally means to rub against the peak. Thus, it is not on the peak, but slightly to one side, as if rubbing against it. Arranging a utensil in this way will evoke its being centered on its kane, while also subtly deprecating it.

†Shibayama’s brief comment involves several complicated word-plays based on the vocabulary of the swordsmith.

——————————————–———-————————————————

Tanaka, meanwhile, begins by narrating what is essentially the same story as was recounted above, regarding the way that the Kogitsunemaru sword came into being -- as it was told to him by a famous swordsmith of his village, named Inoue Sadakane [井上貞包*].

He then concludes his remarks with “hoko [鋒]† refers to the line of the kane. Orienting a utensil so that it is exactly aligned with the very center of that line is called “ma-boko” [眞鋒]; but this is unpleasant‡. [The utensil] should be moved very slightly to the right or left.

“This is what is called mine-zuri no kane [鋒摺りの曲尺]. If we [avoid] ‘hitting’ the edge of the blade, but then [go further by] displacing [the utensil] from the edge, it becomes the way that ordinary utensils are arranged by overlapping [their kane] by one-third**.

“With respect to this [mine-zuri] displacement, it should not be obvious to the eye††. The right way to do this is to barely [displace it] -- it is like Kogitsunemaru’s imaginary hammer, Inari myōjin’s magic hammerman [who aimed his strokes with divine care]. This is the example suggested by the story of Sanjō Kokaji Munechika and Kogitsunemaru. Mine-zuri no kane is explained in this way‡‡.” ___________ *Inoue Sadakane’s dates do not seem to have been recorded, though his blades are renowned and treasured even today.

†Hoko [鋒] means the sharp edge of a blade.

‡It is disliked because arranging a utensil in this way implies that the host treasures his utensil too much. A certain reticence, especially regarding one’s own possessions, is always preferred.

**This interpretation of hoko na hazushi so [ホコナハヅシソ] as being a reference to san-bun-ichi kakari is not subscribed to by any of the other commentators -- and, in the original poem, the implication seems to be that this matter of being (perhaps inadvertently) displaced from its kane is something that should be avoided just as strenuously as orienting the utensil squarely on its kane. Tanaka also seems to be ignoring the construction na...so (that was discussed in sub-note “†††” above), which gives this statement a negative implication. (That said, it is possible that he is arguing that, if the focus of the poem is on the idea of mine-zuri, then displacing the utensil so that it overlaps its kane by one-third is, in itself, an error.)

††At a glance, the utensil will appear (to the guests) to be centered on its kane. It is only the host who will truly know the intention behind the way he has arranged his utensils -- and, in this case, his purpose is to evince humility (even when using a greatly treasured utensil).

‡‡Tanaka’s meaning seems to be that displaying a utensil so that it is exactly centered on the kane is tantamount to a swordsmith’s striking the sword he is creating squarely on the edge of the blade (which, of course, will damage it). The way to preserve the sharpness of the edge is to strike the blade a slight distance away. This idea is then applied to the orientation of a treasured utensil vis-à-vis its kane.

==============================================

◎ If these translations are valuable to you, please consider donating to support this work. Donations from the readers are the only source of income for the translator. Please use the following link:

https://PayPal.Me/chanoyutowa

1 note

·

View note

Text

第二次ハイパーロボット対戦 ※非ガンダム連合編:2nd

※注意書き※

※クロスオーバー注意

※精神的男リョナ注意

※ちょいグロ注意

※デスゲーム&殺し合い展開注意

※ChatGPT-4生成文章

※色々日本語が無茶苦茶

ファルゲン(マッフ)とエルガイム mk-2とレイズナーの死合が見れます。随分マニアックな(人選ならぬ)ロボ選ですね()。

エルガイム mk-2vsレイズナー

あなたは普通に優秀な戦闘デジ��ルシミュレーターです

以下のデータからエルガイム mk-2とレイズナーによる本気の殺し合いをシミュレーションして下さい

ルール

・1対1の闘いが原則である(仲間や援軍を呼んだ場合呼んだ者を即敗北とした後、処刑)

・機体の登場パイロットが死亡するか、もしくは、機体が完全破壊された及び機体が完全停止した側を敗北とする

・各機体の搭乗者は一人とする(仲間とサブパイロットを乗り込ませた場合即敗北とした後、処刑)

・この勝負に敗北したパイロットは強制公開処刑

・パイロットは指定無し

----

エルガイム mk-2とレイズナー、両機体ともに高い性能と多彩な武装を持つが、サイズや重量、機動性から分析すると、以下のようなシミュレーション結果となる。

1. **サイズと重量**: エルガイム mk-2は約23.9m、36.8t。対照的に、レイズナーは約9.52m、13.75tと小さく軽量。サイズが小さいレイズナーは、機動性で優れる可能性がある。

2. **動力と機動性**: エルガイム mk-2はソーラーパワーによって動作し、レイズナーは燃料電池を動力として使用。レイズナーはロケット推力やアポジモーターにより、高度な機動性を持つ。

3. **武装**: エルガイム mk-2の武器は多彩で強力。特にバスターランチャーやパワーランチャーなどのビーム兵器が優れている。一方、レイズナーの速射型レーザードライフルやナックルショットも非常に強力。

4. **戦術**: エルガイム mk-2はプローラー形態に変形することで、地上での高速移動が可能。レイズナーのV-MAX技は、突撃時のエネルギーフィールド発生が特徴。

シミュレーション結果:

戦闘の初め、レイズナーの機動性を生かしてエルガイム mk-2の攻撃を回避しつつ接近。しかし、エルガイム mk-2のプローラー形態での突破攻撃やバインダーからのSマインなどの多彩な攻撃に対応しつつ、ナックルショットやレーザードライフルで反撃。しかし、両機ともに装甲が厚いため、決定的なダメージを与えるのは難しい。

最終的には、エルガイム mk-2の高出力のビーム兵器とプローラー形態の機動性、レイズナーの高度な機動戦術とV-MAX技のどちらが上回るかは一概には言えない。しかし、サイズと火力面でエルガイム mk-2が優れているため、わずかながらエルガイム mk-2が有利と考えられる。

ただし、パイロットの技量や戦場の状況なども大きく影響するため、結果は100%確定的ではないことを理解してください。

V-MAXで特攻してパイロットごと破壊すればいいのでは

V-MAXはレイズナーの強力な技の1つであり、エネルギーフィールドを発生させての突撃が特徴です。この技を使用すると、レイズナーは短時間だけ圧倒的なスピードとパワー���発揮できます。そのため、V-MAXを正確にエルガイム mk-2の弱点に向けて使用す��ば、エルガイム mk-2を破壊する可能性が高まります。

しかしながら、V-MAXの使用はリスクも伴います。特攻はパイロット自身にもダメージを与える可能性があり、また、一度使用した後は一時的にレイズナーの動きが鈍ることも考えられます。そのため、V-MAXを使用するタイミングや状況が非常に重要となります。

もしレイズナーがV-MAXを使い、エルガイム mk-2の予測しづらい位置や弱点に特攻を成功させれば、確かにエルガイム mk-2を破壊する可能性が高まります。しかし、その逆にV-MAXがエルガイム mk-2の攻撃によって中断された場合、レイズナーは非常に危険な状態になるでしょう。

結論として、V-MAXは強力な技ではありますが、成功の鍵はその使用タイミングと状況判断にあると言えるでしょう。

頭部破壊狙いの場合は エルガイム mk-2のコクピットは胸部に、レイズナーのコックピットは頭部にあります

頭部破壊を狙う場合、機体のコクピットの位置は極めて重要です。

1. **エルガイム mk-2**: コクピットが胸部に位置しているため、頭部を狙う攻撃はパイロットにダメージを与えることは少ないでしょう。しかし、センサーや通信機器などが集約されている可能性があるため、頭部を損傷すると戦闘能力が低下する可能性があります。

2. **レイズナー**: コックピットが頭部に位置しているため、頭部への直接の攻撃はパイロットに致命的なダメージを与える可能性が非常に高いです。この情報を知っているエルガイム mk-2のパイロットは、戦略としてレイズナーの頭部を狙うことが考えられます。

シミュレーションを考慮すると、エルガイム mk-2は強力なビーム兵器やバスターランチャーを使ってレイズナーの頭部を狙う戦術を取るでしょう。一方、レイズナーはその機動性を活かして頭部を守りつつ、エルガイム mk-2の胸部を狙うことになるでしょう。

レイズナーのV-MAXを考慮すると、エルガイム mk-2の胸部を狙った特攻も考えられますが、その際には頭部を守ることが非常に重要となります。

結論として、レイズナーのコックピットが頭部に位置していることは、戦略的な観点から大きなディスアドバンテージとなる可能性があります。しかし、正確な戦術とタイミングを持って戦うことで、このディスアドバンテージを乗り越える可能性もあります。

V-MAX特攻するのが一番?

V-MAXを使用した特攻は、レイズナーの主要なトランプの一つです。エネルギーフィールドを発生させての突撃により、大きなダメージを与える可能性があります。特に、コックピットの位置が敵に知られている場合や、一撃で決着をつける必要がある状況では、V-MAXを使った特攻は有効な戦術となるでしょう。

しかしながら、以下の点を考慮する必要があります:

1. **リスク**: V-MAXを使った特攻は非常に強力ですが、同時にリスクも高まります。成功すれば大きなダメージを与えることができますが、失敗した場合、レイズナー自体が大きなダメージを受ける可能性があります。

2. **タイミング**: V-MAXを使用するタイミングは非常に重要です。敵の予測しづらいタイミングや、敵の武装や動きに隙がある時に使用することで、成功率を高めることができます。

3. **他の武器の活用**: レイズナーにはV-MAX以外にも多くの武装があります。これらの武装をうまく組み合わせて使用することで、V-MAXの特攻をより効果的にすることができます。

結論として、V-MAXを使用した特攻は非常に強力な戦術であり、一撃で決着をつける可能性があります。しかし、それを実行するには正確なタイミングと状況判断が必要となります。

勝率比出して下さい

エルガイム mk-2とレイズナーの対決の勝率比を計算するには、各機体のスペック、武装、戦術、そして環境などの多くの要因を考慮する必要があります。以下は、提供された情報を元に、一般的な評価を基にした勝率比の推定です。

**エルガイム mk-2**:

- 有利点: サイズと火力がレイズナーに比べて大きく、多彩な武装を持っている。

- 不利点: 相対的にレイズナーに比べて機動性が低い可能性がある。

**レイズナー**:

- 有利点: 高い機動性とV-MAXによる高威力の特攻技を持つ。

- 不利点: サイズと火力がエルガイム mk-2に劣る。特にコックピットが頭部にあるため、攻撃を受けやすい。

シミュレーション結果として:

- エルガイム mk-2の勝率: 60%

- レイズナーの勝率: 40%

これは一般的な推定であり、戦場の状況やパイロットの技量、そして戦術の選択などによって、実際の勝率は変動する可能性があります。特にレイズナーのV-MAXをうまく活用できるかどうかが、勝敗を大きく左右する要因となるでしょう。

中の人追加で

(※プロフィールのデータ省略)

アルバトロ・ナル・エイジ・アスカとダバ・マイロード、両パイロットともに高い操縦技術を持ち、また非戦闘的な性格を持っています。彼らの性格と信念を考慮して、勝率比を再評価します。

**アルバトロ・ナル・エイジ・アスカ (レイズナーのパイロット)**:

- 有利点: 揺るぎない信念を持ち、高い操縦技術を有している。

- 不利点: 暗い性格と不殺主義者であるため、決定的な攻撃を躊躇する可能性がある。また、メンヘラの性格が戦闘中に影響を及ぼす可能性がある。

**ダバ・マイロード (エルガイム mk-2のパイロット)**:

- 有利点: 高い操縦技術と肉体的な強さを持っている。頑固で、決めたことを最後までやり遂げる性格。

- 不利点: 敵のパイロットを殺さない優しい性格であるため、攻撃を躊躇する可能性がある。

再評価したシミュレーション結果として:

- エルガイム mk-2(ダバ・マイロード)の勝率: 55%

- レイズナー(アルバトロ・ナル・エイジ・アスカ)の勝率: 45%

両パイロットともに敵を殺すことを好まない性格を持っているため、実際の戦闘は戦術や技術的な優越性よりも、彼らの信念や決意が大きく影響すると考えられます。特に、どちらのパイロットも状況に応じて相手の機体を破壊することを避ける可能性があるため、この勝率比は非常に接近していると考えられます。

お互いに不殺主義なので、攻撃と戦法に戸惑い、死合が進まずそのテンポが悪くなることがあると思いますか?

はい、その通りです。両者ともに不殺主義を持つパイロットである場合、以下のシチュエーションや戦術的な特徴が考えられます。

1. **攻撃の躊躇**: パイロットたちはコクピットやパイロットを直接的に狙うような攻撃を避けることが考えられます。これにより、通常の戦闘よりも攻撃の選択肢が制限される可能性があります。

2. **戦術的な動き**: 戦闘の主目的が敵機体の機能を停止させる、または戦闘不能にすることになるため、機体の特定の部分を狙う、または非致命的な武器や技を使用する戦術が取られる可能性があります。

3. **長引く戦闘**: お互いに致命的な攻撃を避けるため、戦闘は長引くことが考えられます。これにより、エネルギーの消耗や機体の損傷が進むことで、戦術の選択肢が変わる可能性もあります。

4. **コミュニケーション**: 両者ともに戦闘を好まない性格を持つため、戦闘中や戦闘前にコミュニケーションをとることで、戦闘そのものを避ける解決策を模索する可能性も考えられます。

結論として、お互いに不殺主義のパイロットである場合、通常の激しい戦闘よりもテンポが遅く、戦略的な動きや非致命的な攻撃が主となる可能性が高いです。また、そのような戦術の選択により、戦闘の流れやテンポが不規則になることが考えられます。

勝利した後により深く後悔するのどっちですか

アルバトロ・ナル・エイジ・アスカとダバ・マイロードの性格を考慮して、勝利後の後悔の度合いを考察します。

**アルバトロ・ナル・エイジ・アスカ**:

彼は非常に��情的な性格をしており、暗い一面やメンヘラ的な要素も持っています。彼の過去の経験から、自分の搭乗機が暴走して人を殺した事実に対して深く悩み、涙を流していることが示されています。このような性格から、もし彼がダバ・マイロードを破った場合、深い罪悪感や後悔に苛まれる可能性が非常に高いと考えられます。

**ダバ・マイロード**:

ダバは優しい性格を持ち、戦闘中も敵パイロットを殺さないように努めています。彼のこの性格は、彼自身の人生や存在意義を深く考える性格から来ていると思われます。彼がアルバトロを破った場合、その行動に対する後悔や罪悪感を感じることは間違いないでしょう。しかし、アルバトロほど感情的に後悔することは少ないかもしれません。

結論として、アルバトロ・ナル・エイジ・アスカが勝利した場合の後悔の度合いは、ダバ・マイロードが勝利した場合よりも深く、感情的になる可能性が高いと考えられます。

どちらかが事故を装い大会の主催者である人間を撃ち屠って死合をなかったことにすることはありますか??

アルバトロ・ナル・エイジ・アスカとダバ・マイロードの性格や過去の行動を基にして、そのようなシナリオの可能性を考察します。

**アルバトロ・ナル・エイジ・アスカ**:

彼は感情的で暗い一面があり、搭乗機の暴走や戦闘による死者に対して深く悩むことが示されています。彼の不殺の信念やその他の性格的特徴から考えると、大会の主催者を直接攻撃するような行動は彼の性格と合致しないと考えられます。ただし、大会自体や戦闘を強要する状況に対する反感や怒りは持っている可能性があります。

**ダバ・マイロード**:

ダバは優しく、他者を傷つけることを避ける性格をしています。彼の人生や存在意義を深く考える性格から、大会の主催者を攻撃するような行動は彼の性格と合致しないと考えられます。しかし、彼もまた、大会や戦闘を強要する状況に対する疑問や不満を持っている可能性があります。

結論として、アルバトロ・ナル・エイジ・アスカとダバ・マイロードの性格や過去の行動を考慮すると、大会の主催者を攻撃して死合をなかったことにするというシナリオは、彼らの性格や信念とは合致しないと思われます。しかし、彼らが大会や戦闘に対して持っている感情や考えに基づいて、別の方法で大会を中止させるような行動をとる可能性は考えられます。

その大会の主催者が邪悪な悪党の場合

邪悪な悪党としての大会主催者が絡む場合、アルバトロ・ナル・エイジ・アスカとダバ・マイロードの対応も変わるかもしれません。

**アルバトロ・ナル・エイジ・アスカ**:

彼の感情的で暗い性格と、不殺の信念を持つ一方で、強い正義感や邪悪に対する反感も考えられます。悪党としての主催者に対して直接的な攻撃を選ぶかは不明ですが、そのような主催者を止めるための何らかの行動をとる可能性は高いでしょう。彼の感情的な一面を考慮すると、一時的な感情の爆発で極端な行動を取る可能性も考えられます。

**ダバ・マイロード**:

ダバは他者を傷つけることを避ける優しい性格でありながら、正義感や困難な状況での決断力も持っています。彼は、邪悪な主催者の行動や目的を静かに観察し、最良の方法でその主催者を止めようとするでしょう。彼���頑固な性格を考慮すると、一度決意した行動は最後までやり遂げる可能性が高いです。

結論として、邪悪な悪党としての大会主催者がいる場合、アルバトロとダバの両方とも、それぞれの方法で主催者の邪悪な行動や目的に反対する行動を取る可能性があります。具体的なアクションは、その状況や背景、彼らの過去の経験や情報によって異なるでしょう。

どちらかが事故を装い大会の主催者(邪悪な悪党)である人間を撃ち屠って、死合をなかったことにすることはありますか??

アルバトロ・ナル・エイジ・アスカとダバ・マイロード、両者ともに戦いを好まず、不殺主義の性格を持っていることを考慮すると、彼らが大会の背後にいる邪悪な主催者に対して共闘する可能性は十分考えられます。

事故を装って主催者を排除する行動は、両者が共通の敵に対して協力し、自らの信念や正義感を守るための手段として取られる可能性があります。特に、大会の目的や主催者の真の意図が彼らの信念や価値観に反している場合、彼らは主催者に対して行動を起こすことを選ぶかもしれません。

ただし、そのような行動を取るには、以下の点を考慮する必要があります:

1. **情報収集**: 大会の真の目的や主催者の意図を知るためには、十分な情報収集が必要です。

2. **計画**: 事故を装う行動は、高度な計画と協調が必要です。両者がしっかりと連携し、計画を実行する能力が問われるでしょう。

3. **結果**: 主催者を排除した後、大会の続行や他の参加者との対応など、さまざまな結果を考慮する必要があります。

結論として、アルバトロとダバが共闘して事故を装い主催者を排除する可能性はあります。しかし、その行動を実行するためには、彼らの信念や正義感、そして計画や連携能力が大きく影響するでしょう。

…。

「レイズナー」と「ファルゲン マッフ」の仕様を理解しました。以下のシミュレーション結果を提供します。

---

**宇宙戦**

*結果*: ファルゲン マッフ 7 - レイズナー 3

ファルゲン マッフは出力や装甲の厚さ、そして武装の多様性で勝るため、宇宙空間での機動性と攻撃能力を活かして勝利します。しかし、レイズナーの速射型レーザードライフルやカーフミサイルも時折ファルゲンにダメージを与えます。

---

**地上(昼戦)**

*結果*: ファルゲン マッフ 6 - レイズナー 4

ファルゲン マッフの合成ゴム「シモーレックス」を用いた装甲は地上での小規模な爆発や衝撃に非常に効果的です。しかし、レイズナーのナックルショットや速射型レーザードライフルが明るい昼間の視界を利用して有効に使用されます。

---

**地上(夜戦)**

*結果*: ファルゲン マッフ 5 - レイズナー 5

夜戦では双方とも視界が制限されるため、近接戦が中心となります。レイズナーのナックルショットやV-MAX(体当たり)がより効果的になり、ファルゲンのレーザーソードも活躍します。結果、双方が均衡を保ちつつ戦います。

---

以上の結果から、全体的に「ファルゲン マッフ」の性能が「レイズナー」を上回るものの、環境や戦況に応じて「レイズナー」も一定の戦果を上げることが確認されました。

中の人載せてやって下さい

「マイヨ・プラート」と「アルバトロ・ナル・エイジ・アスカ」というパイロットを加味したシミュレーションを行います。

---

**宇宙戦**

*結果*: ファルゲン(マイヨ) 6 - レイズナー(アルバトロ) 4

マイヨはエースパイロットとしての経験を活かし、ファルゲンを巧みに操る。しかし、アルバトロの不殺主義による非戦闘的な動きや戦術が時折マイヨを混乱させる。

---

**地上(昼戦)**

*結果*: ファルゲン(マイヨ) 5 - レイズナー(アルバトロ) 5

マイヨの近接戦の苦手さとアルバトロの戦いを好まない性格が両者の動きを均衡させる。双方とも高度な機動戦を繰り広げるが、明確な勝者は出ない。

---

**地上(夜戦)**

*結果*: ファルゲン(マイヨ) 4 - レイズナー(アルバトロ) 6

夜戦の場面で、アルバトロの不殺主義とその信念が更に影響を及ぼす。彼の搭乗機が暴走で人を殺す事実への悩みや涙が、深い闇の中でより一層彼の戦術や動きに影響を与え、マイヨの近接戦の苦手さを利用して数点を稼ぐ。

---

パイロットの性格や背景が戦いに大きな影響を与えることが確認されました。特にアルバトロの不殺主義や過去の経験が彼の戦術や動きに深く影響しており、これがシミュレーションの結果にも反映されました。

…。

0 notes

Photo

お久しぶりの #茶ナル にて #荒巻バンド #荒巻茂生 b #竹内直 sax #吉澤はじめ p #本田珠也 ds (ナル 御茶の水) https://www.instagram.com/p/Bym7seDFbwY/?igshid=q06c3hgkd2af

0 notes

Video

youtube

"Dark Dance" by Tomonao Hara December 5, 2018 at NARU - Ochanomizu, Tokyo

Tomonao Hara Group(原朋直グループ)Tomonao Hara/tp(原朋直)Jun Miyakawa/p(宮川純)Takuma Asada/g(朝田拓馬)Hiroshi Ikejiri/b(池尻洋史)Dennis Frehse/ds(デニス・フレーゼ)

#jazz#Tomonao Hara Group#Tokyo#trumpet#Tomonao Hara#Takuma Asada#Hiroshi Ikejirri#Dennis Frehse#Jun Miyakawa#ジャズ#原朋直グループ#原朋直#宮川純#朝田拓馬#池尻洋史#デニス・フレーゼ#お茶の水#ナル#NARU#Gaumy Jam Records

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

桜林美佐の「美佐日記」(209)

在日米海軍中尉の交通事故、その後

桜林美佐(防衛問題研究家)

───────────────────────

おはようございます。桜林です。「男もすなる日記

といふものを、女もしてみむとてするなり」の『土

佐日記』ならぬ『美佐日記』、209回目となりま

す。

本格的な春の訪れを感じるようになりました。送

別会のシーズンでもあり、私は米国に帰る友達、英

国に行く友達それぞれと会う時間がありました。

最近、気づいたのは、いわゆる女子会とかママ友

会みたいな集まりとみられる女性たちが昼からワイ

ンやビールを飲んでいる姿が多いということです。

で、私もそうしたところに参加��ることがあると、

他の人がみんな当たり前のようにアルコールを注文

することにちょっと驚きます。

他のテーブルを見ると、確かに女子会みんな飲ん

でいる・・・。

私自身はランチミーティング的な感覚しかなく、そ

もそもその後に片付けなくてはならない仕事が残っ

ていたりしますので、長くなりそうなら途中で退席

することになりますが、こういう世界があるんだな

ーと、つい女性グループの昼飲みをまじまじと観察

してしまっています。

ご興味ある方は、平日の昼時に女子好みのお店に

行ってみて下さい。そのようなグループを必ず発見

できることでしょう(ただし、これを発見しても何

の収穫にもなりませんが)。

さて、以前、加藤さんのメルマガでも心配されて

いた在日米海軍の士官が交通事故を起こし85歳の

女性と54歳の男性の日本人2人が死亡した事故に

関して、動きが活発になってきています。

この事故は2021年、当時、横須賀基地に所属

していたリッジ・アルコニス中尉が家族と共に富士

登山をした後に、車を運転して帰る途中で居眠りと

みられる事故を起こしたものです。アルコニス中尉

の家族は「高山病によって意識を失った」と主張し

ています。

禁固3年が言い渡された後に控訴したものの、高

裁判決でも「居眠り運転」という一審判決が支持さ

れました。

家族らは、アルコニス中尉は逮捕されて3週間以上

独房に入れられたために、容疑を晴らしたかもしれ

ない診察を受ける機会を与えられなかったと主張し

ています。

また、同家族は被害者の遺族に100万ドル(約1

億3500万円)以上の慰謝料を払ったとも言って

います。

アルコニス中尉はモルモン教徒で、日本でも宣教

活動をしていたと言います。彼がキリスト教ではな

いということも、この事案が米国全体の感情問題に

まではまだ拡大しておらず、今のところ、一部にと

どまっている要因なのではないかと私は想像してい

ます(日本人は宗教の違いが分からないかもしれま

せんが)。

モルモン教は酒を飲まないため、飲酒運転の疑い

は全くないですが、確かコーヒーやコーラ、お茶も

飲まないはずですので、奥さんと子ども3人を連れ

て富士山に登った帰りの運転は、やはり無理があっ

たと思われます。

この判決を不当として、ユタ州のマイク・リー議

員はアルコニス中尉の米国への送還を求め「トマホ

ークの日本への売却もやめるべきだ」と訴えていま

す。また日米地位協定は日本優位すぎるとも怒りを

あらわにしています。

ユタ州と言えば人口の68%がモルモン教であり、

マイク・リー議員自身もそのようですので、同氏が

立ち上がるのは自然な流れなのだと思います。ただ、

日米同盟をやり玉にあげられていることは、今まさ

に中国を睨んだ両国の防衛協力が最重要である時だ

けに懸念されるとこ���です。

この事件に関しては、ウォールストリートジャー

ナル紙やヘリテージ財団なども日本の司法に対する

不信感やアルコニス中尉の米国への返還が必要だと

表明しています。

アルコニス中尉の妻や協力者たちは「彼を家に帰

して」という署名を集め、カマラ・ハリス副大統領

と面会し、2月7日にはバイデン大統領にも直接訴

えています。

先述のマイク・リー議員はツイッターなどで岸田

首相への批判を強めており、以前ここでも書いた在

日米軍基地のシビリアンに対する医療問題も引き合

いに出し地位協定の不備を訴えています。

日米の外務当局者は頻繁な協議の場を持っている

と聞きますので、おそらく私が心配するまでもなく

話し合いを進めているのだろうとは思いますが、日

本の司法をくつがえすようなことになれば政権にと

って重大な痛手になるでしょうし、一方で、このま

ま米国内の日本への不信感が広がるようなことにな

れば日米関係、特に今、急がれる安全保障体制構築

に影響を及ぼしかねません。

とにかく、日本としては先延ばしにせずに、早期の

円満解決を願うばかりです。

今週も最後まで読んで頂きありがとうございまし

た!皆様にとって素晴らしい1週間となりますよう

に!

1 note

·

View note

Photo

2018/6/13

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

2025/4/29 Otoie at NARU

4/29(火) お茶の水 ナル "音家"

Open13:30 Start14:00 Music charge¥3,500+order

原朋直/tp, 岡勇希/sax, 平倉初音/p, 高橋陸/b, 関根豊明/ds

NARU 03-3291-2321, http://ocha-naru.com

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

【かいわいの時】天正十六年(1588)二月十六日:出雲大社の巫女、大坂天満宮で神歌・小歌踊りを演じる(大阪市史編纂所「今日は何の日」)。

安土桃山時代の公家、山科言経の日記『言経卿記』の同日条に、「出雲国大社女神子色々神歌、又小歌等舞之間」とあります。この女神子が、後に歌舞���を始める出雲の阿国であったといわれています(下記)。『当代記』慶長八年(1603)四月条に「此頃カフキ踊ト云事有。出雲国神子女(名ハ国、但非好女)出仕、京都へ上ル、縦バ異風ナル男ノマネヲシテ、刀、脇差、衣装以下殊異相也」とあり、「かぶき踊」の名称がこの頃に定着したと考えられます。

言経は京都西梅津の土地をめぐる争いがきっかけで正親町天皇の不興を買い、天正13年夏、上京柳原の邸宅を売却して、妻子や冷泉為満・四条隆昌らとともに京都を去り、堺の念仏寺(俗称大寺)の子院明王院に身を寄せます。言経の妻が本願寺の一家衆(一族)興正寺顕尊の親族であった縁を頼って、同じ年の秋に冷泉為満らとともに天満寺内町に移り住んだのです。言経は町家で暮らすようすを日記にしたためました〈略〉言経は市内見物をしたり様々な階層の人々との交流をもちました。寺内町で盂蘭盆会にあわせて催される踊も見物しています。毎月25日の天満天満宮へのお参りも楽しみでした。この日天満宮は、弓行事などさまざまな催し物で賑わいました。とりわけ連歌会は言経が楽しみにしたものです。天満宮には秀吉の御伽衆でもあった大村由己がおり、大坂・天満における文化交流の拠点でもあったのです。また、大村由己宅では出雲大社女神子の舞も見物しています。一説にはこれが、後に歌舞妓を始める出雲の阿国であったともいわれています(野高宏之)。『編纂所だより 28』2007所収「山科言経と天満寺内町」より。

(写真)▼「山三郎お国ら歌舞の図」 『奈良絵本 國女歌舞妓繪詞』1604-30(京都大学附属図書館蔵)所収。表見返しに旧蔵者墨書識語の貼紙あり(青々斎1850)

なごさん(名古山)さまは おくり申さうよ こはた(木幡)まで、こわた山路に 行暮て ふたりふしみ(伏見)の草まくら、八千夜そふとも なごさん(名古山)さまに なごりをしきは かぎり なし。()内編注

お國はもはや念佛踊の衣裳ではなく、男装して銀の長創を挾み、右手に「茶屋のおかか」即ち茶屋の女、後ろに猿若を控え、最後に以上四人*の総踊りの図を以��終つている。*かぶき者(お国)、茶屋のおかか、猿若に加えて名古屋山三の亡霊の四人。

0 notes

Photo

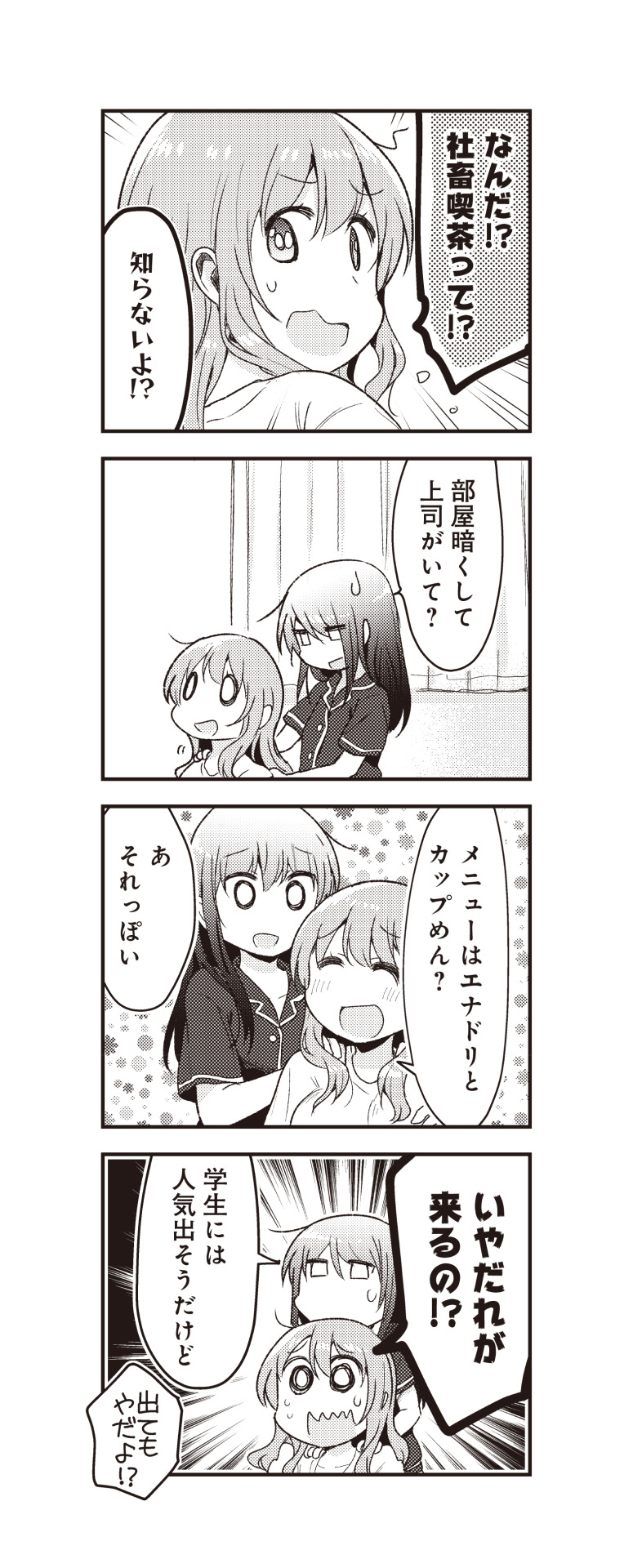

【本日更新!】タツノコッソ先生『社畜さんと家出少女』第34話がニコニコ静画「きららベース」で無料公開中! 文化祭で喫茶店をやることになったユキちゃん。 どんな喫茶店がいいかナルさんにも案を聞いて出たのは…社畜喫茶!? 本編はこちらから! https://t.co/JJFKKcCtTE https://t.co/6VP7TsmlPP Source: https://pic.twitter.com/6VP7TsmlPP

1 note

·

View note

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (8): the Biographies of Nambō Sōkei's Contemporaries (2): Sumiyoshi-ya Sōmu [住吉屋 宗無].

9) Sumiyoshi-ya Sōmu is an authentic chajin of the old school¹.

As an example of this: [before including] that chaire, that chawan, [or] that mizusashi [in a tori-awase], he earnestly scrutinizes [each piece] carefully, so as to thoroughly judge its suitability².

However, with respect to [his] arrangements and other doings, because [he] always does everything the same way, people who lack indepth training [comment that] there is little worth seeing [at his gatherings]³. Yet, even though people say that [his chakai] are uninteresting [when considered superficially]⁴, as a consequence of his focus on [acting in] the moment -- each day, each night -- there is a unique intensity and conviction to everything he does⁵.

[Sumiyoshi-ya Sōmu] prefers to host his gatherings only at night⁶. Because of this, [his] maturity deepens year by year⁷ -- since the night gathering, in particular, [demands] an especially admirable hataraki⁸.

Also, because [Sōmu] has a profound resolve to study Zen, there are many things that make [his chakai] interesting⁹.

Depending on the person, [I] was told that [Sōmu’s] chanoyu is [considered to be] excessively strict¹⁰. Nevertheless, [Ri]kyū praised [Sōmu] even more [because of his adherence to the orthodox way of doing things]¹¹.

At present, though a little creativity might be allowed¹², an excess of hataraki, rather than being a mistake [as it is felt to be nowadays], was, in the past, preferred [over a lack of creativity] -- and would have been judged worthy of praise¹³.

_________________________

◎ In the case of this entry, Shibayama Fugen’s teihon [底本] agrees with the Enkaku-ji text (as printed in the Sadō Ko-ten Zen-shū [茶道古典全集] edition), albeit with the usual occasional differences where one text has a word written in kanji, while the other has the same word spelled out in kana.

And while Tanaka Senshō’s primary source also agrees with the other two (and in the same way), he brings to light the text of this entry as found in a handwritten manuscript of the Nampō Roku that circulated very widely in the Edo period (I have personally seen three different copies of this “popular” version -- one in the collection of a multi-generations-old tea utensil shop Kyōto, one in the personal library of an amateur chajin in Ōsaka, and the third in the library of a Dai Nihon Sadō Gakkai-affiliated scholar in Tōkyō, though his copy has no connection with the one mentioned by Tanaka -- and so I can corroborate Tanaka’s observations). While the bulk of this entry is also the same as in the other sources, the beginning and end of the passage are drastically different -- characterizing Sumiyoshi-ya Sōmu as a maligner of the orthodox tradition. I have included translations of this variant in the relevant footnotes (in sub-note “‡“ under footnote 1, and at the end of footnote 13).

This is an unfortunate consequence of the decision to restrict access to the Enkaku-ji manuscript, while also prohibiting anyone from writing anything down while still within the temple precinct. Perhaps a Japanese scholar of chanoyu will be able to explain why this kind of foolish secrecy was considered a virtue; all I can say is that, so far as I can see and understand, it merely provided an opportunity for errors of this sort to spread, errors which would eventually come back and cast doubt on the veracity original text (once the fallacious version had been disseminated throughout the tea community).

¹Sumiyoshi-ya Sōmu ha, kofū mate-naru chajin ni te [住吉屋宗無ハ、古風眞手ナル茶人ニテ].

Kofu [古風] means old school; someone who follows the original traditions (of chanoyu)*. A practitioner who adheres to the original way of doing things†.

Mate-naru [眞手なる] means true-handed‡, in the sense of someone who does things correctly; someone who is skillful at incorporating the original practices of chanoyu into his gatherings.

I have translated mate-naru with the word “authentic.” __________ *Sōmu incorporated the traditional elements into the format of the chakai formalized by Jōō and Rikyū; he did not stage gatherings in the way that tea was served prior to the appearance of Jōō’s chakai.

†This included the idea of having a very small collection of utensils -- often only one of each of the necessary pieces -- that frequently included things like a magemono-mizusashi if the chajin had failed to acquire an appropriate ceramic or bronze piece.

Collecting a number of newly-made pieces, and playing with the rules of kane-wari to accommodate pieces that were not strictly according to the classical sizes, and trying to create a “fresh” atmosphere by changing many of the utensils each time, was antithetical to the chanoyu that people like Sōmu espoused.

‡This differs quite a bit from the modern sense of this word, which usually means both hands, aligning the hands, left and right (hands) together; or (when pronounced shi-no-te) a character written in the regular script (i.e., a hand-written script that replicates the printed form of the kanji).

Furthermore, Tanaka Senshō mentions an alternate idea that, rather than mate [眞手], the actual word was either matsudaira [眞平] or shinko [眞乎]. Matsudaira would mean something like “[Sōmu] flatly refused (to follow the old teachings).” Shinko has no meaning, but Tanaka believes (since this is what was found in the copy that he reviewed) it was a miswriting of the word matsudaira.

This word-change would characterize Sōmu as an anti-establishment radical (which would make us wonder why Rikyu was so full of praise for his doings). Nevertheless, this theory is based on the text that is found in one of the early manuscripts -- unfortunately one that enjoyed an especially wide circulation from the Edo into the early-modern period.

²Tatoeba kono chaire ni ha, kono chawan, kono mizusashi to, hi-goro kure-gure ginmi-shite sadame-oki [タトヘハ此茶入ニハ、此茶碗、此水サシト、日ゴロクレ〰吟味シテ定メヲキ].

Tatoeba [例えば] means for example.

Hi-goro [日ごろ] means day in and day out, normally, habitually.

Kure-gure [くれぐれ = 呉々] means repeatedly, over and over again.

Ginmi-suru [吟味する] means to examine something very closely; scrutinize.

Sadame-oki [定め置き] means something like to judge (an object’s) suitability -- to verify the fitness of something according to the classical rules and precedents.

In other words, before using any utensil, Sōmu carefully scrutinizes it, to make sure it confirms with things like the teachings of kane-wari. This was different from many of his contemporaries (and even more so, people of later generations), who selected utensils based purely on their visual appeal.

As for what this “careful scrutiny” means, in the case of a chawan, not only should the mouth be of the appropriate size (3-sun 8-bu to 4-sun 2-bu for a small chawan; 4-sun 8-bu to 5-sun 2-bu for a large chawan), but the foot should also be one-third the diameter of the mouth, so that when placed so that the foot is immediately adjacent to its kane, the bowl “overlaps” that kane by one-third.

He makes sure that not only the individual utensils are of the correct sizes, but also that the relationship between them agrees with the classical models, so that after placing one utensil, the positions of the others can be determined easily*. A simple example of this is that, when the chawan is brought out, after the chaire has been moved in front of the mizusashi, the chawan will be correctly aligned with its kane when placed 2-sun, or 1-sun 5-bu, to the left of the chaire.

When, in olden times, they talked about showing ones utensils to a “tea master” in order to judge their suitability, it was to this practice that they were referring†. It is also why Rikyū insisted that something like a chaire be submitted to him when he was asked to make a chashaku for it -- so that he could arrange the utensil on the mat, and so decide what was suitable. For Rikyū, suitability and preference were entirely different matters: he often certified utensils as suitable for chanoyu that he would not personally care to use when serving tea -- because preference is directly connected with the host’s personal likes and dislikes, but suitability is concerned with the rules of kane-wari and tai-yō, and has nothing to do with what anyone “likes” or “dislikes.”

Once the rules of kane-wari and tai-yō were forgotten (after the death of Rikyū and the other masters of his generation), this activity degenerated into the matter of whether the tea master personally liked the object, or not -- which makes this request for a judgement a fallacy‡. This, of course, remains the case today; and it is part of the reason why followers of the orthodox tradition (such as the chajin in Kyūshū) eschewed the practice of iemoto hakogaki -- even when that iemoto offered to sign their boxes for free. ___________ *This is the teaching known as tai-yō [體用].

†Even in the days of Jōō and Rikyū, these teachings were not well known. It was only the followers of the orthodox tradition, the students of people like Kitamuki Dōchin, who were informed in such matters.

Even Jōō, who was regarded as the first master of his generation (on account of his huge collection of meibutsu utensils) did not know these things -- hence his attempt to cultivate Dōchin (who studiously refused to answer his questions -- at least according to the history that has come down to us from that period). Indeed, it was for this reason that Dōchin introduced the young Rikyū to Jōō (since, in his impoverished state, he imagined that Jōō would be able to entice Rikyū into revealing enough of the secrets to assuage Jōō’s curiosity) -- though what Rikyū would tell was probably much less that what Dōchin could have revealed, and that may have been why Dōchin considered Rikyū to be the better vehicle through which to make these matters known. It may also have been why, once he had gained some understanding, Jōō also was not inclined to pass this information on to most of his own disciples, preferring to rest on the laurels of his meibutsu utensils (which implied that the owner also possessed the secrets of their use -- though, if Jōō took care not to use them all that often, and refused to part with them, he would not be challenged to reveal those secrets that he might not have known).

Imai Sōkyū, for example, though married to Jōō’s sister and named the guardian of Jōō’s young son, apparently had not been told, and this was part of the basis for the malicious that he held toward Rikyū -- especially when Rikyū decided to teach the secrets to Jōō’s son Sōga. (And, unfortunately, Sōkyū’s stubborn ignorance became general in chanoyu through his machi-shū followers, which group included Shōan and his son Sōtan, leading to the situation as it exists today.)

‡Where it is extremely rare for utensils, thus certified by the recent generations of grand masters, to conform to the teachings of kane-wari (except in those rare instances where the utensil being appraised was actually carefully copied from one of the old pieces that was so certified by someone like Rikyū).

When the rule is that the professional is not supposed to have any interest in the topic of his profession -- actually enjoying chanoyu, for example, being considered the attitude of the amateur -- we must not expect that the professional will do any more to further his own knowledge than what is minimally necessary in order to maintain the façade of his supremacy. Thus, though the teachings are accessible (if one makes the effort), it has been easier to denounce such things as fraudulent and spurious, than to expend the effort to learn, and then, using that understanding, to correct the misapprehensions of ones progenitors. It is easier to quote sources, when pressed; and if the quoted information eventually turns out to be wrong, it is not the fault of the quoter, but of his source -- and, if the original source has mysteriously “vanished” or “been lost” (which is easy enough to claim when no evidence can be found that the source ever existed in the first place), then it is apparently nobody’s fault at all. The problem with this system should be easy enough to see; but it is, unfortunately, the system on which chanoyu scholarship is, and has (at least since the Edo period) always been based.

³Oyoso oki-awase nado mo, jōjū ichi-yō ni serareshi yue, mijuku no yakara no midokoro sukunaku [凡置合ナドモ、常住一樣ニセラレシユヘ、未熟ノ輩ノ見所スクナク].

Jōjū [常住] means constantly, every time, always.

Ichi-yō [一樣] means unvarying.

Serareru [せられる] means to do (used when describing actions of other people).

In other words, because Sōmu practiced chanoyu according to the original way of doing things (which included the idea of scrutinizing each utensil carefully and only using it when satisfied that it agreed with the classical teachings), his collection of utensils would have been small; and, because of his classical roots, he tended to arrange the utensils and perform his temae in much the same way on every occasion.

An idea of what is being described here can be deduced by looking at Uesugi Kenshin’s [上杉謙信; 1530 ~ 1578] collection (virtually the whole of which is shown in the photo, below).

Here we see that Kenshin -- who was universally acknowledged to be one of Jōō’s principal disciples -- owned a small chawan, a chasen, an ivory chashaku, a large chawan, a temmoku-chawan and temmoku-dai, a shin-nakatsugi (provided with a shifuku)*, a ceramic kake-hanaire, and a bronze oki-hanaire. All of which he kept in a Chinese carrying box. The only other things needed to serve tea would have been a kakemono† and a kama‡ (the koboshi would have been a mentsū [面桶], the mizusashi a magemono piece**, and the futaoki made from bamboo). There are only so many ways in which this small set of things could be arranged††, and so Kenshin, too, would have had very little variation between one gathering and the next. Thus, every time the same people came for tea, the arrangements would have seemed to be the same as well.

Mijuku no yakara [未熟の輩] means immature people.

Midokoro sukunaku [見所少く] means little worth looking at; little to see.

In other words, because Sōmu's arrangements were almost always the same, his fellow chajin (who, because of their inexperience, were unable to understand what Sōmu was doing‡‡) considered his gatherings to be boring. __________ *The karamono ko-tsubo chaire [唐物小壺茶入] known as the Uesugi hyōtan [上杉瓢箪] was not owned by Uesugi Kenshin. It entered his family’s collection when Kenshin’s adopted son Kagekatsu [上杉景勝; 1556 ~ 1623] was given it by Hideyoshi (who had received it from Ōtomo Yoshimune [大友義統; 1558 ~ 1610], as an apology for his having committed a military blunder).

Ōtomo Yoshimune was the son of Ōtomo Sōrin [大友宗麟; 1530 ~ 1587], from whom Yoshimune had inherited this chaire.

†Since imported kakemono were preferred, most practitioners usually had only one scroll.

‡There are no records of the kama he owned,

**For people who had not found a mizusashi, Jōō created the magemono mizusashi.

††The dai-temmoku was only used when serving tea to a nobleman, and the other two chawan would have been used according to the guests to whom he was serving tea.

The kake-hanaire was used when the flower he was arranging was something that grew above eye-level, and the oki-hanaire was used when the flower was something that grew near to the ground. The flower, therefore, determined how it was displayed, so Kenshin had nothing to choose.

‡‡To people unschooled in the orthodox rules and teachings, the continued repetition of the same sort of arrangement would have seemed boring -- especially after Jōō and his followers made frequent changes in their tori-awase fashionable.

The necessary insight is derived from Zen; but, to those who lacked this kind of insight, superficially everything just seemed to be the same.

⁴Kyō-naki-yō ni hito-bito omoi kere-domo [興ナキヤウニ人〻思ヒケレドモ].

Kyō-naki-yō ni [興なきように] means lacking in entertainment/amusement value; uninteresting; boring.

⁵Sono hi・sono yo no setsu ni ōji, omoi-ire aru-koto wo serareshi nari [其日・其夜ノ節ニ應ジ、思入アルコトヲセラレシ也].

Sono hi・sono yo no setsu ni ōji [其日・其夜の節に應じ] means “as a consequence (ōji [應じ]) of the unique aspect of each particular occasion (setsu ni [節に]*), on that day or night (sono hi・sono yo no [其日・其夜の]) when the gathering occurred.”

Even though the utensils are all the same, and the temae is the same, it was Sōmu’s ability† to manipulate these things, and his sense of presence, that made each occasion seem unique, memorable.

Omoi-ire [思い入れ] means things like earnestness, intensity (of feeling), devotion, and single‐mindedness.

In other words, Sōmu was able to use his utensils with total conviction, and this attitude projected itself to (those of) his guests (who were open to receiving it).

This sentence hints at the Zen training‡ that underpins everything he does; Sōmu is constantly “acting in the moment.” __________ *Setsu ni [節に] is difficult to translate, because the equivalent words in English are not used in the same way. It means things like seasonality and temporality, but it also includes the nuance of a specific chance (a favorable or fortuitous concatenation of circumstances) or opportunity (a suitable moment).

†This is the result of complete familiarity. Sōmu was absolutely comfortable with each of his utensils, so he did not have to expend any thought on the mechanics of using them.

‡See footnote 9, below.

⁶Moppara yo-kai wo kononde [專夜會ヲ好テ].

Moppara [専ら] means things like only, solely, exclusively.

Yo-kai [夜會] is the preferred pronunciation, in the context of chanoyu*.

Kononde [好んで] means preferably; ones preference; (doing something) by choice. ___________ *Probably because the more usual pronunciation, ya-kai [夜會], sounds too much like yakkai [やっかい = 厄介], which means troublesome, bothersome, a nuisance (which many students of chanoyu consider the yo-kai to be -- on account of the numerous “troublesome” rules and conventions that were concocted over the course of the Edo period, and into the early 20th century).

⁷Toshi-doshi jukushi-keru yue [年〻熟シケルユヘ].

Toshi-doshi [年々] means year by year.

Jukushi-keru yue [熟しける故]* means “because (yue [故]) becomes more mature (jukushi-keru [熟しける]).”

In other words, “because, year after year, Sōmu’s maturity increases....” __________ *In all other versions of this entry, the word is jukushite [熟して] meaning to (have) become ripe.

⁸Yo-kai hitoshio shushō ni hatarakare-shi nari [夜會一入殊勝ニハタラカレシ也].

Hitoshio-shushō [一入殊勝]: hitoshio [一入] means especially, conspicuously, prominently; shushō [殊勝] means things like admirable, laudable, commendable, praiseworthy. Thus, and especially praiseworthy (hataraki).

At a night gathering, the host has total control over the lighting, and in this way he can manage the effect much better than if he were limited by the light that comes in through the windows (since it naturally changes with the passage of time).

⁹Zen-gaku ni kokorozashi fukakari-shi yue, ki-mi omoshiroki-koto ōshi [禪學ニ志フカヽリシユヘ、氣味面白キコト多シ].

Zen-gaku [禪學] means the study of Zen, practicing Zen.

Ki-mi omoshiroki-koto ōshi [気味面白いこと多い], more literally, means “there are many things that give a feeling of interest (to his chakai).”

¹⁰Hito ni yori chanoyu, shimeri-sugutaru to ittari [人ニヨリ茶ノ湯、シメリ過タルト云リ].

First of all, this sentence is mispunctuated (at least as it is quoted in the Sadō Ko-ten Zen-shū). The first phrase should be limited to hito ni yori [人により].

Also Sōmu’s name, which precedes the word chanoyu (and so indicates that the chanoyu that is judged to be “too strict” is Sōmu’s chanoyu), is missing from that version.

Shimeri-sugitaru [閉めり過ぎたる] means to become exceedingly strict, to be extremely rigid.

Once again, the reference is to Sōmu's adherence to the teachings of kane-wari, together with the mannerisms associated with things like the gokushin-temae. To people used to chanoyu performed with a more casual or lighthearted approach, this kind of tea would likely strike them as being highly mannered and inflexible.

¹¹Kyū ha ichi-dan homerare [休ハ一段ホメラレ].

Kyū [休], of course, means Rikyū.

Ichi-dan [一段] means even more, still more, much more.

Homeru [譽める] means to praise, admire.

¹²Ima sukoshi hatarakase-taku ha are-domo [今少ハタラカセタクハアレドモ].

Ima [今] means now, at present. Though whether this refers to Nambō Sōkei's time (which was also when Rikyū and Sōmu were alive and active), or (perhaps more likely) the first century of the Edo period, is not really clear from the text.

Hatarakase-taku [働かせたく]* seems to mean to make use of ones hataraki; employ ones creativity.

Are-domo [有れども] means something like "even though (a little creativity) is acceptable....†" __________ *Unclear. Perhaps the -taku component is a parallel case to taku [炊く, 焚く, 燒く], meaning to set on fire, set to boiling, kindle, fire up, and so forth. In other words the mechanism by which one expresses their hataraki.

Notably, both Shibayama Fugen’s teihon and that used by Tanaka Senshō have hatarakase-do ha [働かせ度は] rather than hatarakase-taku ha. Hatarakase-do means “the degree of hataraki” (i.e., “how much” hataraki) that will be employed (in a given situation).

†More literally, “even though (a little creativity) exists....” Creativity is being used to translate the word hataraki, since the meaning and nuance are similar.

¹³Hataraki sugi-taru ayamari yori ha, haruka ni mashi nari to, izure yori mo homesare-tari [ハタラキ過タルアヤマリヨリハ、遙ニ增ナリト、イヅレヨリモ被賞タリ].

Hataraki sugi-taru [働き過ぎたる] means when the hataraki becomes excessive.

Ayamari [誤りより] means more than being wrong, far from being erroneous.

Haruka ni [遥かに] means far away, in the distance, remote -- the word is used both spatially, and also temporally (and here, specifically, it is referring to the separation in time; “in the past”).

Mashi [増し] means preferable, better than, less objectionable, the lesser of two bad options.

Homesare-tari [誉めされたり] means to be praised, worthy of praise.

In other words, while it might seem that too much hataraki (creativity) would be wrong today, in the past, at least, this option was preferable to too little hataraki.

Once again, the widely-circulated manuscript mentioned by Tanaka (see the last sub-note under footnote 1) has a different ending. After the words “Rikyū praised [Sōmu’s hataraki] even more” (see footnote 11), the entry concludes with: ika-sama hataraku-bekitsubo ni, nani-koto mo naki-koto ga naki-yō ni mo omowaruru, tadashi, hataraki no sugi-tari yori ha maji no aru-beki [イカサマハタラクベキツボニ、何事モナキ事ガナキヤウニモ思ハルヽ、但、ハタラキノ過タルヨリハマジニアルベキ].

This means: “certainly, when [circumstances demand that] one needs to [display] his hataraki, in every case -- as long as what [you want to] do is not impossible -- it seems to be [allowable]. However, excessive hataraki is not desirable.”

Perhaps the last sentence is a veiled criticism of Sōmu’s behavior.

1 note

·

View note

Text

2021年8月以降の演奏予定

8/11(水) 成城学園前 カフェブールマン 初共演 ファルコン(g)

8/15(日) 仲町台 Tommy's By The Park 17:00"ZCLOCCA QUOKKA" 松尾由堂(g)

延期になりました。8/22(日) 吉祥寺 Strings 17:30 栗林すみれ(pf)ソロ

8/28(土) 柏 Nefertiti 13:00 松丸契(as)

9/ 2(木) 18:00金山 Mr.Kenny's "sumireiko" 山本玲子(vib)

9/ 4(土) 高山 飛騨高山ジャズフェステイバル "sumireiko" 山本玲子(vib) 無観客ライブ配信

9/ 7(火) 渋谷 公園通りクラシックス19:00 "くりばやしばやし" 林正樹(pf)

二重奏北海道ツアーは延期となりました。

9/10(金) 室蘭 MUTEKIROU "二重奏" 金澤英明(b)

9/11(土) 蘭越 パームホール 18:30 "二重奏" 金澤英明(b)

9/12(日) 函館 jazz spot Leaf 17:30 "二重奏" 金澤英明(b)

9/20(祝月)14:00 渋谷公園通りクラシックス sumireiko10周年記念コンサート 山本玲子vib

9/24(金) 中野 スイートレイン "二重奏" レコ発 金澤英明(b)

中止となりました。9/25(土) 御茶ノ水Naru 14:00 太田剣Quartet 西嶋徹(b) 河村亮(ds)

9/26(日) 本八幡 cooljojo 14:00 蜂谷真紀(vo,voice)初共演

9/28(火) 渋谷 公園通りクラシックス 19:30 西嶋徹(b)

9/29(水) 中野 スイートレイン 石井智大(vn) 金澤力哉(b) 高橋直希(ds)

10/ 2(土) 朝霞台 停車場 千北祐輔(b) 大井澄東(ds)

10/ 6(水) ��谷 公園通りクラシックス "二重奏"レコ発 金澤英明(b)

10/ 9(土) 水戸 Girl talk 18:00 石井彰(pf)

10/11(月) 横浜 エアジン 栗林すみれ(pf) ソロ

10/13(水) 渋谷 公園通りクラシックス 19:30 福盛進也(ds)

10/15(金) 中野 スイートレイン 中牟礼貞則(g)

10/20(水) 柏 ナーディス 小牧良平(b) 高橋直希(ds)

10/22(金) 小岩 COCHI 荻原亮(g)

10/23〜二重奏 東北ツアー

※変更になる場合があります。御来場前に必ずご確認下さい。詳細は各お店ごとにお問い合わせ下さい。

二重奏 東北ツアー

10/23(土) 秋田 THE CAT WALK

10/24(日) 弘前たけや(この日のみピアノソロ)

10/25(月) 盛岡 すぺいん倶楽部

10/27(水) 多賀城 HARI☀️SUN CAFE

10/28(木) 山形 Noisy Duck

10/29(金)高畠ちゅうしん蔵

10/31(日) 南陽・川西 3蔵巡り

11/ 4(木) 渋谷 公園通りクラシックス 19:00 "くりばやしばやし" 林正樹(pf)

11/ 8(月) 金山 Mr.Kenny's 19:30 "二重奏 Ⅲ" レコ発 金澤英明(b)

11/ 9(火) 豊橋 BUZZLE BUNCH 19:30 "二重奏 Ⅲ" レコ発 金澤英明(b)

11/10(水)沼津サティ 二重奏

11/13(土) 御茶ノ水 NARU 太田剣カルテット

11/14(日) 上福岡 音喫茶 一乗 18:00 "二重奏 Ⅲ" レコ発 金澤英明(b)

11/27(土)丸ノ内コットンクラブ "Remboato"リリース記念ライブ(1st set only)

12/3 山形ノイジーダック shiho vo

12/4 多賀城 shiho vo

12/9(thu) 19:30 池袋アップルジャンプ セバスティアンカプティーンds DUO

12/19(sun) 14:30OPEN 15:00START 成城学園前カフェブールマン ファルコンgt MC=3300円 +2drinks order

12/21(tue)鹿児島ジャズフェス

12/25 公園通りクラシックス nagalu presents 『3 pianos』 2台のグランドピアノと更に小型ピアノ”ピアニーノ”を導入しお送りするスペシャル企画!

栗林すみれ (p)林正樹 (p)佐藤浩一 (p)guest 福盛進也 (ds)

open: 19:00/start : 19:30 reservation/door : ¥4,000

ご予約・お問合せ:公園通りクラシックス 03-6310-8871 koendoriclassics.com

協力:ALT.NEU.Artistservice Co,.Ltd 主催:nagalu

12月31日(金)大晦日のDUO 渋谷公園通りクラシックス 西嶋徹b 開場15時00分/開演15時30分 3,500円

1/6(thu)柏ナーディス 小牧良平b高橋直希ds

1/9(sun) 吉祥寺strings 栗林すみれソロ

1/13(木) 公園通りクラシックス 2台ピアノ with石井彰p

1/15 本八幡cool jojo 蜂谷真紀vo

1/22 小岩コチ 類家心平tp

1/29 御茶ノ水ナル 太田剣カルテット

1/30 U3chi 藤本一馬gt

0 notes