#タクミくんシリーズ 長い長い物語の始まりの朝。

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

School Culture & Male Androphilia in Japan

[This is part of a series on Takumi-kun 6. The aim of this piece is to discuss the origins of student culture and male androphilia & how it plays out in Takumi-kun series.]

Takumi-kun series is an early BL novel by Shinobu Gotoh with an enduring legacy. It is also an on-going work as we follow Takumi-kun and others beyond their student (gakusei) days and into adult (shakaijin) life.

Takumi-kun series is mostly set in an all-males boarding school Shido Academy. As I have mentioned in my previous posts, pre-modern Japan has a long tradition of male androphilia[1], much of which was age-stratified, class-stratified or both and involved strict/normative inserter/insertee dichotomy. BL has inherited (such as in seme/uke dynamics) and bastardized (such as with younger seme/older uke pairing) traditions of male androphilia in its tropes. Let's discuss a bit of the history before diving into how Shinobu Gotoh plays around with the setup of boarding school male-male sexuality that emerged in the Meiji period.

Part 1

[ Main resource used for this part of the write-up is the chapter titled “Toward the Margins: Male-Male Sexuality in Meiji Popular Discourse” from the book Cartographies of Desire: Male-Male Sexuality in Japanese Discourse, 1600-1950 by Gregory M. Pflugfelder. ]

What Review of Senryu From Meiji Japan Reveals

Meiji period Japan saw transformation of Japanese customary male-male sexuality ‘within the newly established framework of a centralized nation-state’.

…male-male sexuality, which had enjoyed a prominent and respectable place in Edo-period popular texts, came during Meiji times to be routinely represented as “barbarous,” “immoral,” or simply “unspeakable.”

The marginalization of male-male sexuality can be traced through its representation in senryü verse composed during that period. In post-Meiji Restoration popular humor Yoshichö districts of Edo well-known for organized sex work was no longer associated with the kagema or male sex worker. Instead, it was associated with female geisha, mirroring the 18th centuary decline of kagema teahouse and their shutdown by local authorities'. Once mainstream male-male sex work had to go underground and faded from popular memory.

Just as old customs were forgotten, new ones emerged in senryu of 1880.

Two figures […] associated with male-male sexuality were the bantö and detchi—clerk and apprentice, respectively, in a commercial house. The bantö wielded considerable authority over other employees, and had been portrayed in senryü since the Edo period indulging his lechery with young male coworkers. The detchi, on the other hand, may be seen as the merchant version of the priestly chigo or samurai page boy: male adolescents for whom the favor or disfavor of senior males might have significant consequences for their professional advancement.

Meanwhile male-male sexuality involving Buddhist priests went from being considered ‘a lesser transgression than fornication with women’ and a ‘contradiction between the priest's personal indulgence and the ascetic ideals of his religion” to an “emblem of “ancient evils” (kyühei) in dire need of reform’ and ‘a criminal offense’.

Following period saw state regulation of representation of sexuality in media (print media, theatre and paintings - artist Kawanabe Kyösai’s erotic drawing of Meiji oligarch Sanjö Sanetomi & a male foreigner landed him in jail; not much different from jailing of ero BL creators in present day[2]) and a shift in popular discourse that deemed that male-male eroticism has no place in the “civilized” environment of Meiji. Male-male sexuality was further marginalized through silence resulting from ‘state censorship, editorial discretion, authorial inclination, public taste’, etc. Meiji journalists continued reporting on male-male sexuality but adopted a tone of moralistic outrage and condemnation.

In the demarcation of civilized behavior, male-male sexuality was relegated to ‘the Japanese past, the southwestern periphery, and the world of adolescence’.

Japanese Past

‘Male-male erotic practices lay in the past’ which was seen as ‘a backward and “feudal” age, whose institutions and customs Japan must abandon in order to achieve “civilization.”’

Meiji era authors depicted male-male sexuality with historical backdrop (such as samurai society of the Sengoku and Edo eras) that would excuse their representation in the name of historical accuracy. [This is in contrast to say depiction in cinema which has largely avoided depiction of nanshoku with exception of Taboo (1999) and Kubi (2023).]

Pflugfelder gives a couple of examples:

Higeotoko (Man with a Beard; 1890–1896) by Köda Rohan – very shonen ai about the whole thing – involved light hand-holding and fade to blank.

Kagema no adauchi (Kagema's Vendetta; 1899) by Jöno Denpei –about a professional “love boy”. As a person born in 1832 Jöno was familiar with male sex workers like the protagonist from his childhood. But the practice has thoroughly disappeared from the cultural fabric by 1899 that Jöno had to introduce the protagonist whose profession was “disgraceful” “from today's perspective” and his gender identity ambiguous.

Marginalization of Male-Male Sexuality Was Japan's Southwestern Periphery

Centered around Kagoshima prefecture (the former domain of Satsuma), the region encompassed various parts of Kyushu, Shikoku, and Honshu. During the Meiji period, it was popularly believed that male-male erotic practices were more prevalent here than in the rest of Japan. Other than the obvious geographic distinction, there was a social reason too for this distinction. It was believed the region was a stronghold of old customs with lasting imprints of samurai class and the high concentration of warrior families. Satsuma had customary homosocial groups with strict sex-segregation practices such as hekogumi and gojü until the Restoration.

Male-male erotic interaction […] was reportedly common within such groups.

… the martial ethos of the samurai class slowly dissolved under the pressure of social change and “civilized morality.” Contemporary observers correlated the deterioration of shiki or “warrior morale” with a decline in male-male erotic practices.[3]

During the Meiji period, southwestern region (Kagoshima in particular) was known for its male-male sexual practices. These practices were seen as regional peculiarities, distinct from the mainstream culture centered in Tokyo. The southwestern region was viewed as a “feudal” backwater, and the association of male-male erotic practices with this area underscored their perceived “uncivilized” nature. Instead of being seen as a universal practice [the way shudo was percieved], male-male sexuality was considered a “folkway” (füzokü) surviving on the cultural margins of a newly “civilized” nation-state. In the 20th century, sexologists further marginalized these practices by diagnosing regions like Kagoshima with a hereditary condition called “regional same-sex love” (chihôteki döseiai). This effectively contained male-male sexuality within specific geographical and cultural boundaries.

Moreover, from Kagoshima men’s regional identity imperial navy and seafaring got associated with male-male eroticism in Meiji Japan.

male-male sexuality & the world of adolescence

… the sexual object in shudö had always been defined as a young male. In Meiji popular discourse, as in that of the Edo period, it was generally understood that youthfulness formed one of the conditions of male-male erotic desirability. More and more commonly, however, the desiring party too was presumed to be an adolescent, older than his partner as a rule, but neither of them yet an adult.

‘Adolescence (seishun) as an “institutionalized moratorium between childhood and adulthood” [allowed for a] social space where adult standards did not fully apply’. This also allowed male-male sexuality which had gained the status of uncivilized behavior to be excused as ‘youthful folly’.

Institutions of formal education were around since Edo period and so was male-male erotic practices in them. Not only that but also ‘violence between rivals in love’. Following the Restoration, schools mushroomed throughout Japan with an added emphasis on education as a vehicle for social mobility. Students, tasked with future nation building, were expected to be diligent in their study and to stay away from sexual diversion. Male-male sexuality in schools were not just that in discourse of the day but was inextricably linked with ‘shifting definitions of masculinity, regional and political rivalries, and the ongoing “civilization” of morality’.

Mori Ögai - father of Mori Mari who wrote the first BL

Two terms born out of Mori Ögai's 1909 novel critiquing naturalism[4] Wita sekusuarisu (Vita Sexualis) köha and nanpa were used in discourses surrounding male-male sexuality among students. The term köha (translated as “roughnecks” by Pflugfelder and “queers” by Kazuji Ninomiya and Sanford Goldstein) referred to students who eschewed interest in male-female eroticism instead engaged in male-male sexual relations. This was in contrast to their nanpa (translated as “smoothies” by Pflugfelder and “mashers” by Kazuji Ninomiya and Sanford Goldstein) classmates.

[These are penetrator roles but not fixed categories. Students did move from one category to another even in Mori's novel. "Boy" (shonen) who were penetrated could take up penetrator role later on.]

“Smoothies” […] did not tuck up their sleeves or swagger about with menacing shoulders like their “roughneck” peers, but instead dandified themselves in silk kimonos and white socks (tabi) in order to win the favor of women.

In Mori’s school köha student were mostly from Kyushu and southwest Honshu prefecture of Yamaguchi while nanpa were from northeastern region. This regional distinction shows up in Tsubouchi Shöyö's novel Tösei shosei katagi (Spirit of Present Day Students; 1885–1886) wherein Kiriyama Benroku a quintessential köha is a native of Kyushu who wears coarse garb and is contrasted against his classmates womanizing peers not only by his leaning towards samurai ideals of masculinity but also by his interest in his companion Miyaga.

The köha-style of masculinity was modelled on engaging brute strength even in erotic dealings. Moreover ‘the strict age hierarchy that prevailed in student society constrained the very notion of consent, since junior males were in principle supposed to obey the dictates of senior schoolmates.’

In such an environment, male-male sexual practices often took a predatory form, with younger students providing fodder for older ones.

However, there were also non-forced köha-shonen sexual relations too.

Mori describes, for instance, a set of crude hand signals whereby a “boy” could consent to or refuse a senior male's overtures; subtler forms of seduction involved treats, favors, and the prospect of “special protection” (tokubetsu na hogo) by the older party.

Meiji newspapers was eager to cover köha violence wherein the older students who preyed upon “beautiful boy” in the streets of Tokyo and other Meiji cities or fought over a “beautiful boy”. They stood to gain readership especially those from middle- and upper-class who were likely to send their kids to boarding schools. It also fit well in the political context with journalistic crusade aimed at male-male sexuality & exploitation as a “Satsuma habit” in a time when ‘domination of the national government by the so-called “Satsuma clique” (Satsubatsu) faced mounting criticism’.

The portrayal of köha by journalists in post-Restoration Japan led to a strong association between male-male sexuality and adolescence. This association was so strong that any discussion of male-male sexuality would inevitably reference student societies and dormitories as common places for such relationships. Furthermore, accounts of school life often highlighted the culture of male-male eroticism as a distinctive feature. This is evident in memoirs by several notable figures such as Ösugi Sakae (himself a former köha), Iwaya Saza-nami, Ubukata Toshirô, as well as in literary works by Dazai Osamu, Hori Tatsuo, Kawabata Yasunari, Mushanoköji Saneatsu, Origuchi Shinobu, Satomi Ton, Tanizaki Jun’ichirö, and Uno Köji.

Chigo-nise ties (that is, erotic relationships between junior and senior youths) were reportedly common [in Kagoshima] as late as the 1940s, while student memoirs and other accounts describe similar attachments in schools outside the region. With the twentieth-century rise of the notion of [döseiai] “same-sex love,” however, popular representations of such relationships would come increasingly to focus on their psychological features, rather than on physical predation of the Meiji type.

The other half of the ‘asymmetric dyad that made up a male-male erotic relationship’, the sexually penetrated partner, is referred to as ‘shonen’ (boy) in student lingo. By then a mix of inherited knowledge from various arena – Japanese past, classical Chinese, and contemporary forensic pathology – entered public discourse such as seen in Kömurö Shujin's Bishönenron (On the Beautiful Boy).

In Kömurö Shujin's work, the primary effect of this paradigm was to bring to the fore the psychology and physiology of the “beautiful boy” in a manner that would become increasingly common as the century progressed. Kömurö Shujin cited an impressive array of Western authorities on “same-sex love,” most of them doctors or scientists who believed that the “passive” partner in male-male intercourse differed from others of his sex on the basis of certain mental and physical peculiarities, both inborn and acquired. At the same time, the author's understanding of Western sexology was filtered through a set of native assumptions, emerging in a form that often differed in telling ways from the intentions of the original theorists.

Masculinity of wakashu was rarely ever problematized during Edo period. But with the medicalization of male-male sexuality led to attribution of “effemination” with “passive” partner put forth by Western sexologists as Richard von Krafft-Ebing to gain traction in Japan and persist.

[Parallels can be found in bishonen (beautiful boy) stock in BL deemed feminine by readers unfamiliar with the bishonen aesthetics. For example, misattribution bishonen Ayase even when contrasted with feminine Someya in No Money. This also extends to treatment of seme/uke dynamics as though it is a reflection of heterosexual pairing when it is in fact a pairing of two different masculine aesthetics, not to ignore the misogynistic, xenophobic and colonial conception of men who do not fit into specific masculine aesthetics being deemed unmanly/feminine.

Interestingly, Miki Koichiro the director (and screenwriter) of Pornographer, Given, Zettai BL, Bokura no Micro na Shuumatsu etc. is well versed in the male androphilic traditions (among other queer traditions). We can see him using the term “shonen” when instructing the young actor playing Mob-san’s brother’s friend who has a crush on Mob-san. His usage was perfect, proving that he knows what he is doing.]

Part 2

Relics of traditional androphilia in Takumi-kun series

The norm or at least the expectation is that senior students (senpai) pursue pretty boy (bishonen) juniors (kouhai).

This is what outsiders expect even within the universe the novel series is set in as is seen from the conversation between Gii, his best friend Akaike Shouzou and Namiko (Shouzou’s girlfriend) in Sorera Subete Itoshiki Hibi (Those Were Precious Days), a part that never got live action adaptation.

This plays out in Takumi-kun series in various ways. There are two notable bishonen in Takumi-kun’s batch: Gii with his exotic beauty and the princess-like Takabayashi Izumi. In case of pursuit of Gii plays out in a pretty straight forward manner. He is relentlessly chased by seniors who are interested in Gii and their numerous attempts at wooing him.

Takumi-kun 4 - Gii & Sagara

Notable pursuer is Sagara Takahiro who was in the third year when Gii joins Shidou. Sagara as the school president organized many recreational events hoping Gii would participate and they would grow closer. But Gii refuses to participate except for in the final one which took place in Sagara’s absence, the Shinto Shrine Hunt event that is depicted in Takumi-kun 6. Even though the pursuit plays out straight forwardly, it come to nothing since Gii is not there to be pursued. He is there to pursue Takumi-kun.

In case of Takabayashi Izumi, he turns his most ardent pursuers into a band of followers. This obedient little group of lackeys help him to stir up trouble for his love rival Takumi. Moreover, Takabayashi is one of Gii’s pursuers. This pursuit also doesn’t yield any result as Gii doesn’t entertain any pursuit.

Thus, both bishonen of Takumi’s batch subverts expectations surrounding bishonen by being pursuers.

Takabayashi’s plot gets further complicated when he falls in love with Yoshizawa Michio. Their pairing is that of weak seme x weak uke type – both are reluctant to actively pursue each other and requires external intervention to set their ship in motion.

Meanwhile Misu Arata wishes to be the target of his senior Sagara Takahiro’s affections. He actively participates in Sagara’s events wanting to get close [and they do get close as schoolmates] but Sagara is only interested in Gii.

Takumi-kun 4 - Shingyouji & Misu

Misu’s plot further deviates from the pursued bishonen track when a junior (Shingyouji Kanemi) pursues and eventually gets together with him in a clear inversion of the norm.

Takumi is also pursued by his seniors. Aso Kei’s pursuit is depicted in Takumi-kun 6 while Nozaki Daisuke’s attempts at courtship is depicted in Takumi-kun 1.

Aso Kei is the only one Takumi is comfortable interacting with apart from Katakura Toshihisa (Takumi’s best friend). Aso’s pursuit is aided by Gii who wholeheartedly wishes for Takumi’s happiness irrespective of whom he gets together with. Gii creates opportunities for Aso and Takumi to meet by delegating library duty to Takumi when Aso is around thus getting them to interact. Aso’s courtship fails and he takes it out on Gii by showing off – he lies to him that Takumi agreed to shrine hunt with him. When Gii notices that Takumi doesn’t reciprocate Aso’s feelings, he decides to actively pursue Takumi and turns from Aso’s enabler to rival in love.

Nozaki Daisuke’s pursuit of Takumi plays out within the senior pursuing junior set up. Another classic trope is that of love rivals fighting over a bishonen with both literary and in real life precedents. This is evoked in a race between Gii and Nozaki in Takumi’s name from Takumi-kun 1. Here the love rival’s competition is complicated since Gii is a bishonen who is fought over by many others (Takumi, Takabayashi, Nogawa Masaru*, etc).

* Nogawa Masaru is not depicted in any of the movies as far as I can remember.

Even though the novel series is called Takumi-kun series, there are many parts that doesn’t involve Takumi-kun and some of them are exclusively from the point of view of other characters. All in all, Takumi-kun series is like an anthology of many many love stories involving characters who are directly or indirectly connected to Takumi-kun. There are other stories involving younger pursuer and older pursued with all sorts of seme/uke arrangements. Here are some that I can recall right away:

Even guys who are not androphilic such as Akaike Shouzou gets pursued by seniors (Shibata Shun in Shouzou’s case). But these courtships are doomed from the get go.

Younger guy pursues older – senior & junior, teacher & student, etc.

senior x junior pursuit abandoned to establish senior x senior romance (Moriyama & Shibata) or junior x junior romance.

senior x junior romance sometimes end in heartbreak. (Takumi-kun 2)

senior x senior relationships are abandoned in pursuit of senior x junior relationship.

Sometimes seniors employ their seniority to retain power imbalance. (Misu and Shingyouji)

In case it is not clear, who pursues who has got nothing to do with who is seme, uke or riba and vice versa. Since the novel series involves many pairings, we get to see all sorts of seme/uke/riba dynamics (if we are to call it that given Takumi-kun is a June novel).

-

Footnotes

[1] I prefer using male androphilia because queerness is a bit too vague and in most case in inappropriate since it was the norm. Academics usually use male-male sexuality, male-male desire, male-male eroticism, etc. Male androphilia must not be confused with the narrower term homosexuality.

[2] Danmei author Tian Yi and her companions were sentenced for 10 years for profiting from obscene content on male-male sexuality.

[3] while the courting of “beautiful boys” was a “barbaric custom” (banpü), domain authorities during the Edo period had tacitly encouraged it as a means of preventing young men from going “soft” (nyüjaku) through erotic involvement with women (joshoku).

[4] In the Company of Men: Representations of Male-Male Sexuality In Meiji Literature by Jim Reichert (199-208)

-

Takumi-kun meta series

1.Trailer plus

2.School culture and male androphilia in Japan. (you are here)

3.How does the movie compare with the source novel?

4.How does the movie compare with previous adaptations?

#takumi kun series#takumi-kun 6#japanese bl#タクミくんシリーズ 長い長い物語の始まりの朝。#タクミくんシリーズ#Gotoh Shinobu#Takumi-kun Series 6: The Morning of the Beginning of a Long#Takumi-kun Shirizu 6#タクミくんシリーズ6#Takumi-kun: The Dawn of the Long Tales#takumi kun 6#takumi kun 1#takumi kun 2#takumi kun 3#takumi kun 4#takumi kun 5#Takumi-kun Series 1: And The Spring Breeze Whispers (2007)#Takumi-kun Series 1: And The Spring Breeze Whispers#Takumi-kun Series 1#Soshite Harukaze ni Sasayaite#Takumi-kun Series 2: Rainbow Colored Glass (2009)#Takumi-kun Series 2: Rainbow Colored Glass#Takumi-kun Series 2#Takumi-kun Series 2: Nijiiro no Garasu#Takumi-kun Series 3: The Beauty of Detail (2010)#Takumi-kun Series 3: The Beauty of Detail#Takumi-kun Series 3#Takumi-kun Series 3: Bibou no Detail#タクミくんシリーズ3「美貌のディテイル」#タクミくんシリーズ3

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

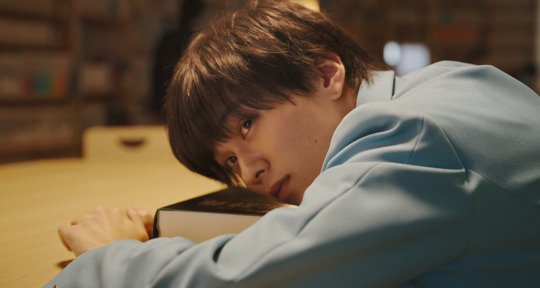

nakayama satsuki in 'takumi-kun series 6' interview (2023)

#nakayama satsuki#cloudiegifs#my gifs#jdrama gifs#タクミくんシリーズ 長い長い物語の始まりの朝#タクミくんシリーズ#takumi-kun series#takumi-kun#takumi-kun series 6#takabayashi ikumi#中山咲月#i love his smile#nakayama satsuki gifs

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

人気学園BL映画『タクミくんシリーズ 長い長い物語の始まりの朝。』森下紫温×加藤大悟「意図せず、ギイとタクミの関係に」撮り下ろしインタビュー

http://dlvr.it/SqPRRB

0 notes

Photo

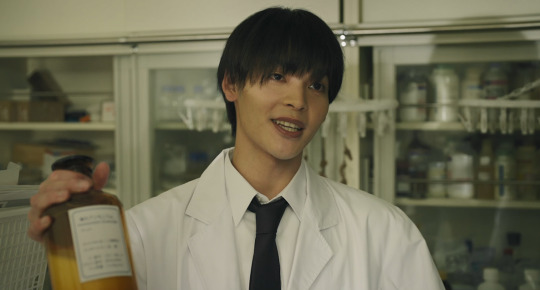

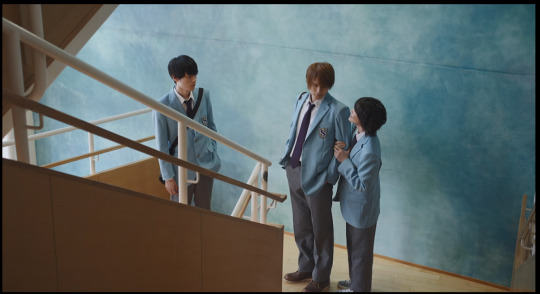

Takumi-kun Series 6: Nagai Nagai Monogatari no Hajimari no Asa | Official Trailer

Japanese Movie - 2023

~~ Adapted from the novel series "Takumi-kun Series" (タクミくんシリーズ) by Gotoh Shinobu (ごとうしのぶ )

Okay I feel like I should revisit all the previous five movies and GIF them now. This is a remake of the first one, which holds a special place in my heart. But very interested to see because of how far Japanese BL’s have evolved since way back in 2007.

#Takumi-kun series 6#LGBTQ+#Romance#Youth#Gay Male Lead#High School#Adapted from a Novel#Japan BL#Asian Movie#Japan#Morishita Shion#Kato Daigo#Takahashi Rio#Nakayama Satsuki#Uemura Souta#Nagashima Ryunosuke#Post: Trailer 2023#Takumi-kun Series 6: The Morning of the Beginning of a Long Long Story#タクミくんシリーズ 長い長い物語の始まりの朝

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Takumi-kun 6 – trailer plus

Takumi Kun Series: The Dawn of The Long Tales

youtube

[Here’s a bit of an introduction to characters and plot. Covers the material directly lifted from the description box of the trailer. Contains mild spoilers.

The movie has been fan-subbed by @furritsubs.]

Introduction

The beginning of Takumi and Gii’s sparkly days

Over 15 years since the first 2007 film adaptation of the Takumi kun Series, a popular “boys’ love” novel series with over 5 million copies in print, a new series has been launched with a new cast and story. The film is a combination of three titles from the Kanzen-ban 1 (omnibus edition) of the original novels—

Akatsuki wo Matsumade (tr. Until I Wait for the Dawn)

Soshite Harukaze ni Sasayaite (tr. And Then, I Whisper into the Spring Breeze)

Nagai Nagai Monogatari no Hajimari no Asa (tr. The Morning of the Beginning of a Long, Long Story).

[This is the order in which the stories appear in the omnibus edition. Third story is new addition to the novel series.]

It portrays Takumi’s encounter with Gii on the day of Shido Academy’s entrance exam and the beginning of their sparkly days.

Takumi Hayama, one of the main characters, is played by Shion Morishita, a new actor stepping into the spotlight in 2023

Giichi Saki (Gii), the other main character, is played by Daigo Kato, who is a musician as well as a cast member of musicals Touken Ranbu and HYPNOSIS MIC Division Rap Battle Rule the Stage.

Other fresh talent in the cast adds vibrance to Shido Academy:

Satsuki Nakayama of Kamen Rider Zero One as Izumi Takabayashi

Rio Takahashi, who models for magazine MEN’S NON-NO, as Shozo Akaike

Yusuke Noguchi of Hi☆Five as Toshihisa Katakura

Souta Uemura, an actor popular with teenagers, as Michio Yoshizawa

Ryunosuke Nagashima, who performed in HYPNOSIS MIC Division Rap Battle Rule the Stage, as Kei Aso

Kosei Tsubokura from a play called Promise of Wizard as Kenji Suzuki

Tsubasa Kizu, who acted in the stage adaptation of Tokyo Revengers, as Arata Misu

Screenwriter Hiroko Kanasugi and Director Kenji Yokoi, the same duo from the previous film who know the Takumi kun Series inside and out, are back together again. With a new screenplay and a new cast, they light the torch to the beginning of a beautiful, sparkly Takumi kun Series.

Story

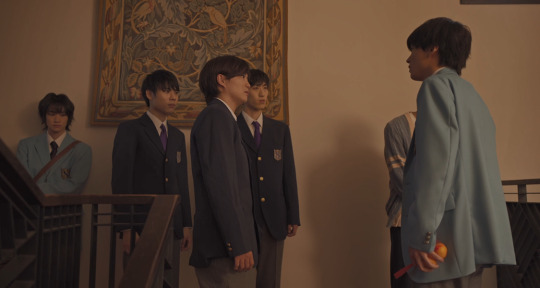

On the day of Shido Academy’s entrance exam, Takumi witnesses Gii for the first time--

On the day of Shido Academy’s entrance exam, Gii (Giichi Saki), who stands out in a crowd with his striking presence, walks past Takumi Hayama in the hallway. Takumi is mesmerized by Gii’s exotic, attractive appearance.

[fan-subbed by furritsubs]

When school starts, Takumi is treated like a freak by his classmates because of his fear of touching and being touched by other people.

But Takumi manages to get by, thanks to Toshihisa Katakura, his only good friend and roommate in the dorm. However, the peaceful days don’t last very long.

In the library, third-year student Kei Aso asks Takumi to participate in the campus “shrine hunt” event with him.

Izumi Takabayashi, who’s head over heels in love with Gii, and students who idolize Takabayashi start picking on Takumi.

When Takabayashi realizes that his beloved Gii not only shrugs him off but is also interested in Takumi the freak, he gets consumed with jealousy and masterminds an attack on Takumi.

Spring comes, and Takumi and Gii are now second-year students. They’re assigned to the same room in the dorm, and their relationship gets much closer.

Then Takabayashi makes another move and drives Takumi into a corner. Gii realizes Takabayashi’s plot and tries to save Takumi, however...

And thus starts Takumi and Gii’s long, long sparkly story.

-

Fan-subbed by furritsubs

-

This post is planned as a part of a series:

1.Trailer plus (you are here)

2.School Culture & Male Androphilia in Japan

3.How does the movie compare with the source novel?

4.How does the movie compare with previous adaptations?

#takumi kun series#takumi-kun 6#japanese bl#タクミくんシリーズ 長い長い物語の始まりの朝。#タクミくんシリーズ#Gotoh Shinobu#Takumi-kun Series 6: The Morning of the Beginning of a Long#Takumi-kun Shirizu 6#タクミくんシリーズ6#Takumi-kun: The Dawn of the Long Tales#multi bl#asian lgbtq dramas#asian bl series#asianlgbtqdramas#jbl#takumi kun 6#japanese gay#japanese films

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

学園BLの金字塔実写化!映画『タクミくんシリーズ 長い長い物語の始まりの朝。』予告編&場面写真16点一挙解禁

http://dlvr.it/SkbcbC

0 notes