#“the best north african player? certainly not moroccan”

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"just because you are moroccan it doesn't mean you have to care about moroccan players" I say, as I'm absolutely going to judge you for being moroccan and not caring about moroccan players

#when i see moroccans acting all superior and big like:#“ziyech? overrated”#“hakimi? overrated”#“bounou? overrated”#“morocco? i mean we got lucky”#“the best north african player? certainly not moroccan”#all I think is: why u gotta downplay ur own people like this while u also stan white players so bad?#what kind of western brainwashing is that

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Constantine – As told to me by my Grandma

One of my favorite books, Invisible Cities, by Italo Calvino portrays a surrealistic journey through imaginary magical cities. Despite its actual existence, I have always imagined Constantine, Algeria as one of the cities portrayed in Calvino’s book. Constantine’s ancient history and its dramatic scenery of mountains and bridges certainly justify its legendary appeal. However, my connection to Constanine goes deeper than that as it is the hometown of my grandparents. And even though chances of visiting are slim, Constantine is alive in my imagination through the stories told to me from early childhood and through the flavors and aromas of the dishes prepared in my grandma’s kitchen, such as Algerian couscous (see recipe below).

(Above: A city view of Constantine)

Despite these vivid memories, the story of the Constantine Jewry and the Algerian community in general, one of the largest Sephardic communities, is widely unfamiliar. Growing up in Israel, being of an Algerian ancestry was somewhat exotic. In a country that thrives on stereotypes of different Jewish ethnic groups, there are no jokes about Algerian Jews, simply because they are not widely represented in society. Given various reasons, primarily the weak Zionist infrastructure in Algeria during the first half of the twentieth century and the strong Francophile sentiments, most of Algerian Jews live in France. My family first immigrated to France and then to Israel the 1970’s. A smaller percentage immigrated to French Canada and to the United States and finally Israel.

But even in France, where most of them reside, Algerian Jews go practically unnoticed and often confused with their regional neighbors, Tunisian or Moroccan Jews. Benjamin Stora, a leading historian in France and a native of Constantine, refers to this phenomenon in his semi family memoire-semi historical book, Les Trois Exils. Juifs d'Algérie- The Three Exiles of Algerian Jewry (from French H.M.):

“The image of Sephardi Jews in France is normally associated with the Tunisian Jews in the movie "Truthfully, I am not lying” marching on the shores of Deauville or bustling around the Santier quarter. These are clichés, of course, but they fit the image of (Jewish) people from Tunisia or Morocco ... But where, are the Jews of Algeria? Their "invisibility" in the French society is striking. It is only at time of death that we learn that a certain personality was born there, as it was recently the case with (philosopher) Jacques Derida” (Stora, 9).

Stora argues that the “invisibility” and in some cases the hiding of the Algerian past of well-known figures (including, Nobel price winners, Olympic champions, authors, philosophes, film producers and fashion designers) stems from deep assimilation of Algerian Jews in French society. In fact, it seems that most Algerian Jews, including members of my family, identify themselves simply as French Jews. In order to explain this phenomenon, Stora unfolds his historical thesis, titled like his book, the three exiles or the three major shifts, which gradually pushed Algerian Jews to blend in French culture.

The First Exile, the depart from Jewish tradition, happened in 1871 (approximately 40 years after Algeria was annexed to France) when Algerian Jews were granted French citizenship. The collective naturalization, also known as the Crémieux Decree, opened the door for Algerian Jews to integrate in the French society, and as a result drastically changed the face of the community. Eagerly, Jews fostered French as their main language instead of Judeo-Arabic and Ladino, enrolled their children in French public school, acquired jobs in the French colonial administration, joined the French army, and participated in the national and municipal elections. The exposure to western ideas and way of life gradually diminished the supremacy of traditional rabbinical authorities. The secularization was encouraged by the French state, which imported “modern” rabbis from mainland France to Algeria, and enforced a pledge of allegiance to France in religious institutes. Within this framework, Constantine was the exception. The city, which was known in the pre-French era as “Little Jerusalem” because of its many Talmudic scholars, remained rather respectful to Jewish tradition. Yet, Constantine was not entirely exempted from the general trends, and according local records, eating shellfish post prayer time with the rabbi was a not a rare sight.

(Above: A photo from a French public school in Constantine. My mother’s cousin, Annie, is in the first row, first on the right).

While the mass naturalization presented Jews with great opportunities, it also sparked strong anti-Semitic sentiments among the European settlers in Algeria, who called for the abrogation of Cremièux Decree. The animosity against the Jews was nourished from Old Catholic anti-Jewish myths and later fueled by the racial ideologies spread in Europe in the first half of the twentieth century. Under this uncomfortable climate, Jews did their best to prove their absolute devotion to France and its ideals. However, they were not successful, as in some cases, the colonial propaganda, spurred hostility between Jews and Muslims. The pogrom in Constantine (August 3-5, 1934) was the most infamous example for that. During three days 23 Jews were murdered by their Muslim neighbors as French law enforcement officers did nothing to stop the violence. In age 93, my grandma still recalls the state of fear while hiding from the Muslim rioters.

The bloodshed in Constantine was a sad prelude to the Second Exile: the bitter rejection from the Patrie or the denial of their French nationality under the sovereign of the pro-Nazi collaborationist Vichy regime during World War II. In 1940, Marshal Philippe Pétain, the former World War I hero, who was appointed by the Germans to rule the southern part of France and its colonies overseas, pleased both the Germans and the racist settlers by immediately abolishing the Crémieux Decree, and promulgating a set of anti-Jewish laws, aiming to remove the Jews from positions of power. One of the most traumatic measures was the banishment of Jewish students from the French public schools and universities. My Grandma was one of those students summoned to the principle’s office. When asked if she was Jewish, she proudly shares how instead of feeling ashamed, she lifted her head up and replied “yes”.

(Above: My grandma in Constantine)

(Above: My grandma in constantine, in the second row, wearing a white outfit)

Beyond the legal restrictions, the loss of their French citizenship was mentally painful. Algerian Jews could not grasp how their beloved France, which they served loyally, turned its back to them. One of the responses to the circumstances was the foundation of the French resistance group, which consisted mostly of Jewish members. Fearing a direct German intervention, many young Jews chose to take an active stance and clandestinely assist the Allies’ attempt to establish a new front in North Africa by landing on the shores of Algeria. On November 8, 1942, after months of preparations, the resistance staged a Coup-d'etat, and took over the capital Algiers by neutralizing the police headquarter, several army camps and the local radio station. The successful execution of their plan, assured the smooth landing of the Allies, and in the longer run paved the way for the Allies’ victory in the North African campaign in World War II. Israeli researcher, Gita Amipaz Silber, who studied the resistance closely, argued the members were motivated by their “Jewish pride”. Nonetheless, testimonials of former members, backed by other academic works, show that they operated as French patriots striving to bring France back to its original pre-Vichy values.

The restoration of their civil rights and the fall of the Vichy regime did not end the tragic chapter in the history of Algerian Jews. The postwar era and particularly the emergence of the Algerian National Movement, created an uncomfortable environment for the Algerian Jewry. The hierarchy between Jews and Muslims created by French colonialism, forever tarnished the relationship and created a rupture that is still present in France today (as demonstrated in Maud Mandel’s excellent book, Muslims and Jews in France: History of a Conflict). Therefore, the Third Exile was the physical exodus of Algerian Jews from their native birthplace to their aspired homeland, France. Indeed, the immigration experience was relativity easy as many Jews were able to retain their old positions in French administration (as did my grandfather), and there were no language barriers. Yet, many emigrants kept longing for their original home across the Mediterranean.

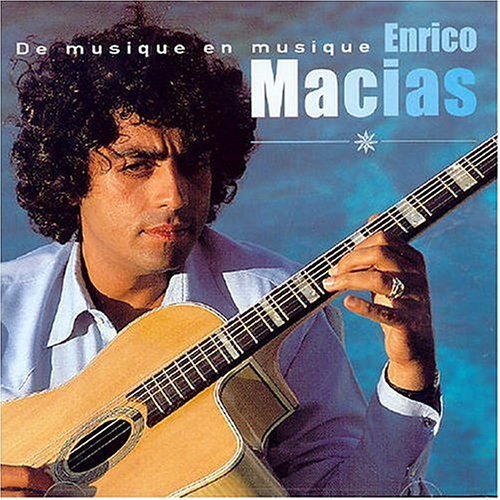

Perhaps the one, who captures best this spirit of yarning, is Singer Enrico Macias, an old neighbor of my Grandma in Constantine (so she claims). Macias’ lyrics discuss both the experience of immigration, the actual boarding on the boat and the looking back at the white rocks; alongside the amazement with the new land, and primarily its elegant capital, Paris. In addition, Macias is a virtuoso guitar player, and his melodies inspired by Andalusian and Arabic music traditions, add a beautiful oriental twist to his French singing. One of my favorite songs, Non je n'ai pas oublié- No, I haven’t forgotten (click the hyperlink for English lyrics and video) is an example of the tension between past and present. He is much admired the general French public and he has a special place in the French hall of fame next to Edith Piaf and Charles Aznavour.

(Above: Enrico Macias)

Music is not the only reminder for Algerian Jews about their origin. Food also plays an important role in maintaining cultural distinction. Within my grandma’s French bubble in Israel, which included frequently serving endives salad, baguette avec beurre, Camembert cheese and apple tart (not to mention that TV-5 was almost always in the background), there was a special place for traditional dishes. Being located on the southern- western shores of the Mediterranean, the Jewish Algerian Cuisine is heavily influenced by the aromas of the Iberian Peninsula. The repopulation of the North African communities with Spanish and Portuguese refugees after the Spanish expulsion (beginning in the late 15th century) definitely added to this strong Iberian thread, which includes dishes, such as Merguez sausage, sautéed spinach with garbanzo beans, ground beef triangle pastels and fried fish. There are also classic North African dishes, such as Macbooba (burnt vegetable salad), honey dipped dough cigars, Mafroom (potato stuffed with ground beef) and, of course, Couscous (recipe ahead). Thus, in a nutshell, Algerian cuisine can be defined as Sephardic-Mediterranean kitchen with North African accents and a French touch.

And now for the Couscous. Algerian Jews are very particular about their couscous. They will never eat it in a restaurant, or out of the box, and refuse to even taste couscous made by Jews from other North African communities (i.e. Tunisian, Moroccan and Libyan Jews). Their couscous (and I am just echoing everything I heard growing up) is superb because its refined texture resembling tiny sand grains, its minimal seasoning (other than Merguez, Algerian cuisine is not spicy) and its perfectly cooked vegetables (not too mushy- not too hard). In other words, or as they put it themselves, it’s the French version of couscous! It is truly incredible how one dish can encapsulate so much attitude!

In their defense, the making of Algerian style couscous, the way my grandma and my mom cook it, is very laborious. In the few times, I made it myself I used shortcuts, such as substituting a food processor for manually sifting the grains over and over again. In addition to the rewarding nature of the process, the final result is very delicious and hearty. During Friday night dinners at my grandma house, everybody was waiting for this one dish, this white mountain decorated with colorful vegetables in an unassuming glass bowl. Despite the abundance of foods on the table, my grandma and my mother always had to go back to the kitchen to refill the bowl. These days I am glad to witness my young son devouring a plateful of my favorite semolina nosh.

Before finally handing the recipe, a couple of helpful notes:

A. Couscous is a seasonal dish. The cold winter months are ideal for filling your stomach with it.

B. Toppings may change. In my household, we served it with garbanzo beans, turnips, zucchinis and carrots. Hard boiled eggs are also a great addition. Some people like eating couscous with a zesty salad (shredded carrots in lemon) or raw vegetables (radishes) on the side.

C. Sauce is traditionally meat based. However, couscous is veggie friendly, and the sauce is delicious also in its vegetarian version.

D. Clear some time. This is not a quick recipe and even with shortcuts, the process of steaming and sifting the grains several times, is quite long even for experienced cooks.

E. The cooking of Couscous requires a special pot called a couscoussier, a traditional double-chambered steamer. For those who don’t have it, a pasta pot with a steamer or just placing a steamer or a colander on a regular pot should work as well.

(Above: My mother making couscous)

My Family Recipe for Couscous

Couscous Grains

Ingredients:

2.2 Ib. (1 kg) semolina (thick grain)

(About) 5 cups water

5 tbs. oil

1 tbs. salt

Directions:

-Fill a large pot with water and bring to a boil.

-Place semolina grains in a big fine mash strainer on top of a large bowl. Pour water over the grains (1 ½-2 cups) and knead the grains, so they will absorb the water. Then sift them through the strainer. Try as much as possible to avoid little balls. Use food processer if you are having difficulty in creating this fine texture.

-Put the grains in the steaming basket on top of the boiling water in the couscoussier (or your alternative pot), cover and cook on medium heat for 30 minutes.

-Remove from heat and place the grains in the strainer again on top of the bowl.

-Once you are done sifting, pour additional 3 cups of water, oil and salt.

-Mix the grains in the bowl and use hands to create tiny little grains.

-Put the grains back in the steaming basket and steam for additional 30 minutes.

-Pour the grains in in a bowl and let cool.

(Repeat the sifting and steaming process for a third time if the grains are too coarse).

Couscous Sauce

Ingredients:

3 cups of garbanzo beans soaked overnight

4 zucchini peeled and cut halfway through

4 carrots peeled and cut halfway through

3 small turnips quartered

2 lbs. meat – beef or lamb (optional)

3 bay leaves

Salt and Pepper

Directions:

-Layer ingredients in a big pot in the following order: garbanzo beans, meat, bay leaves and vegetables.

- Cover with water and bring to a boil on high heat.

- After 40 minutes reduce heat to simmer, add salt and pepper and cook for another 2 ½ to 3 hours until vegetables, meat and beans are soft but not too mushy. Remove bay leaves.

(Above: The different stages of the process)

For serving:

Place couscous grains in a bowl. Arrange vegetables, meat and beans on top and add one or two scoops of the sauce. Basically just to moisten the grains a little bit. Pour the rest of the sauce in a separate sauce for extras.

Bon Appetit!

0 notes