#// of course ozus would be up for it they love money

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

[PROFIT] ASTARION suggests selling the completed crown. (if they ever get to complete it, that's it ❤️)

( equinox event prompts. || accepting! )

*

❝ sell it? ❞ ozus regards astarion with a wide-eyed look and a slightly bewildered part of their lips. the deer-in-headlights look doesn't last for much longer before they relax a bit, a smile curling onto their lips. ❝ how much do you think we could get for it? a lot? ❞

*

—@charmsperson—

#asked & answered.#charmsperson#EquinoxEvent_2023#// of course ozus would be up for it they love money

1 note

·

View note

Photo

A Leaf in a Stream.

The matriarchs of Minari—Youn Yuh-jung and Han Ye-ri—talk to Aaron Yap about chestnuts, ear-cleaning, dancing, Doctor Zhivago and their unexpected paths into acting.

A delicate cinematic braid that captures the sense of adventure, sacrifice and uncertainty of uprooting, Lee Isaac Chung’s Minari might be the closest approximation of my immigrant experience on the big screen yet. Sure, Arkansas is a world of difference from New Zealand. But those dynamics and emotional textures of a family in the process of assimilation—authentically realized by Chung—remain the same.

The film is a wonder of humane storytelling, with the American-born Chung encasing deeply personal memories in a brittle, bittersweet calibration that recalls the meditative, modest glow and touching whimsy of an Ozu or Kore-eda. As Jen writes, “To describe Minari? Being embraced in a long, warm hug.” Or perhaps, it’s like Darren says, “floating along peacefully like a leaf in a stream”.

Neither is alone in their effusive praise. Minari rapidly rose to the top of Letterboxd’s Official Top 50 of 2020, and by year’s end our community had crowned it their highest-rated film. Despite its cultural specificity—a Korean family shifting to the Ozarks in the 1980s—the film has transcended barriers and stolen hearts. Run director Aneesh Chaganty says, “I saw my dad. I saw my mom. I saw my grandma. I saw my brother. I saw me.” Iana writes, “Its portrayal of assimilation rang so true and for that, I feel personally attacked.” The versatile herb of the title, Kevin observes, is “a marker of home, of South Korea, but it can grow and propagate as long as there is water.”

Though a large portion of Minari was vividly drawn from Chung’s childhood, a few of the film’s most quietly memorable moments were contributions from its Korean-born cast.

Youn Yuh-jung as Soonja in ‘Minari’.

Veteran actress Youn Yuh-jung, who’s extraordinary as the visiting, wily grandmother Soonja, traces the origins of the scene where she cracks open a chestnut in her mouth and hands it to seven-year-old grandson David (Alan Kim), to her time living in America. “I’ve seen one grandmother visiting at the time—we don’t have chestnuts in Florida—she brought them all the way from Korea. Actually it was worse than the scene. My friend’s mother brought [the] chestnut. She chewed it and spit it out into a spoon and shared it with her grandson. Her husband was an Irishman. He was almost shocked. We didn’t do that, but I shared that kind of thing with Isaac.”

Most viewers watching this scene will likely recoil in horror, as David does, but co-star Han Ye-ri, playing Soonja’s daughter Monica, notes the practicality of the gesture: “If you give a big chunk to children they could choke on that, so it’s natural for them to do that for their children.”

In another brief, beautifully serene scene—one that is so rarely depicted in American cinema that it’s almost stunning—Monica is seen gently cleaning David’s ears. Han came up with the idea. “Originally it was cutting the nails for David,” she says. “Cleaning your wife and husband’s ears is such a common thing in Korea. Initially the producer or somebody from the production opposed the idea because they regarded it as dangerous, but because it is something that is so common in our daily lives I thought we should go with the idea.”

Neither actress comes from a traditional movie-oriented background. With no acting ambitions, Youn began her fifty-year career with a part-time job hunt that led her to distributing gifts to an audience at a TV station. “It was freshman year from college and they gave me pretty good money. So I thought, ‘Wow, that’s good!’.”

“I’m kind of ashamed about that, as nowadays all the kids plan their future,” she says. “When I talk to the younger generation, they start having dreams about being an actor in the sixth grade. In the sixth grade, I was just playing—nothing. I didn’t plan anything. [Laughs.]”

Han Ye-ri and Noel Kate Cho in ‘Minari’.

Before acting, Ye-ri trained as a professional dancer, and while she wasn’t specifically inspired by movies to cross over into acting, she was an avid film watcher in her formative years. “Working as an actress made me realize how many films I’ve seen growing up.”

“My first memory of a non-Korean-language film left such a strong impression on me, especially the ending,” she says. “The film is called Doctor Zhivago. I saw it on TV and not in theaters. The first film I saw in theaters was Beauty and the Beast. But even growing up I remember because Koreans love films so much they would have films on TV all the time. I watched a lot of TV growing up because both my parents were busy, and in retrospect that really helped become the basis of my career. [Laughs.]”

She also grew up “taking reference from Miss Youn’s body of work to study from, as did many other actresses”. Grateful for the opportunity to work with her on Minari, Ye-ri says, “On set working with her, it made me realize how wonderful it is that this person still carries her own distinct color and scent. And seeing her taking part in this production in a foreign country—she’s over 70—it just really encouraged me that I should be more fearless like her.” She adds: “One of the things that I really want to learn from her is her sense of humor but I think I’m going to have that for my next life. [Laughs.]”

As for Youn’s adventures in early movie-going, she recalls the first Korean film she saw with her father was the 1956 historical drama Ma-ui taeja, based on a popular Korean fairy tale. “I was so scared. I cried so my father had to take me out of the theater.”

“At [the] time, we always had to watch the news on the screen before the movie. It started with a national anthem and every audience from the theater would need to stand up and pledge to the Korean flag. It’s a very stupid thing for you guys but it was like that 60 years ago.”

Han Ye-ri as Monica in ‘Minari’.

For Minari fans who want to discover more of Youn’s work, she recommends starting with the first movie she made with the late, great director Kim Ki-young, Woman of Fire—a remake of his own 1962 Korean classic The Housemaid. “A long time ago I couldn’t see it. Of course I first saw it when it was shown at the theater back when I was twenty. But later on we had a retrospective, so I saw that movie 50 years later. Wow, he was very genius. I was very impressed. That time we had censorship and everything but with that crisis he made that film. That was a memorable movie to [me].”

Youn admits finding it difficult to be emotionally invested watching a film starring herself, including Minari. “It’s terrible, it’s killing me,” she says. “I always think about why I did this and that scene like that. I’m just criticizing every scene so I’m not enjoying it at all.”

Asked which films she enjoys, she offers: “Some other people’s movies like Mike Leigh and Kore-eda Hirokazu. Your Chinese movies I fell in love with. Zhang Yimou when he started. Then later on when he became a big shot, I don’t enjoy [them]. [Laughs.]”

During the shoot, members of the cast and crew caught Lulu Wang’s The Farewell, 2019’s powerful, heartfelt Chinese-American immigrant story. While Youn missed it (“I was just staying home trying to memorize the lines and resting”), Ye-ri watched with interest: “That film also had a grandmother character, so did ours, and these two are completely different. But at the same time from both films you can feel the warmth and thoughtfulness of grandmothers in different ways. To me they are both very lovely films.”

Of her recent viewings, Ye-ri reveals she found Soul made her as emotional as Minari did. “It made me look back at how I live and my day. It’s not necessarily for children but I think it’s a film for adults. [Pauses.] I’m Thinking of Ending Things. I love that film also.”

‘Minari’ is out now in select theaters across the US and other territories, with virtual screenings available to US audiences in the A24 screening room.

#minari#a24#lee isaac chung#lulu wang#the farewell#hirokazu koreeda#Youn Yuh-jung#han ye-ri#han yeri#steven yeun#korean film#korean director#korean films#letterboxd

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

yes that was phrased badly idc abt Hollywood specifically so just 30-60s stuff in general mhm. And if you have some recs of your own that would b lovely thank u <3

i was abt to amend my original answer before u sent this nfdjkfdsnjfd but: keep in mind that with older films its up to archivists/preservationists etc to make them accessible to modern audiences which is of course a matter of money and is very heavily influenced by the western world+critics which will always prioritize their own white cinema. AND i only speak english and a lot of older, non-english movies simply werent made with export to english-speaking countries in mind so even if i were able to find a copy of some older movie i wouldnt be able to watch it anyways unless someone had prepared a translation. ANYWAYS w all that said heres some recs i can give. im starting w the 20s because theres some i wanna rec there too

within our gates (1920)

picadilly (1929)

apart from you (1933) - mikio naruse would be a good one to explore as hes a little less talked about though ive only seen this so far

kurosawa, mizoguchi, masaki kobayashi, ozu obviously

gate of hell (1953)

godzilla (1954)

the bedford incident (1965)

pather panchali (1955), the big city (1963) and the hero (1966) - satyajit ray is another major name here, but unfortunately south asian cinema is a huge blindspot for me still which i hope to fix this year lol

jigoku (1960)

all night long (1962)

hiroshima mon amour (1959)

pigs and battleships (1961)

deus e o diabo na terra da sol (1964)

black orpheus (1959) - the racial politics of this one are a little iffy imo but it is a beautiful movie

la noire de... (1966) and mandabi (1968) - sembène is really good

pitfall (1962)

the house is black (1963)

the night of counting the years (1968)!

soleil o (1970)

i am somebody (1970)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

University Challenge 2019/20, Episode 37: THE FINAL

UNICHALL FINAL, BRAP BRAP! An Oxbridge versus a Russell Group! Boys! Shirts! ’What will we do on Monday nights?’ said Andy, bewildered. I didn’t know how to answer him.

‘Well, I hope you enjoy it,’ said Jez, with the same grim smile as a man about to make eight chaps walk a plank into a pool of sharks.

Corpus Christi, Cambridge (CCC): 105

Imperial College: 275

Team Vibe: Corpus Christi, Cambridge:

Imperial:

Grandad Count: Imperial were slightly the older, with an average age of 23.

Gender Diversity Count: Yes, well, I knew it was coming. 8 boys (at least some racial diversity in there). Props to Captain Wang for this:

Style News: Quite a few jackets and open-necked shirts in there, like they’d all got an invite to their first party with their lecturers to drink mid-priced white wine and chat about trans-dimensional strings. Not Brandon of course, bringing in another of his delightful sweatshirts - this one had an iconic Greek NYC deli advert on it – plus, of course, his ‘NOT HERE TO MAKE FRIENDS’ badge. Captain Wang of CCC also brought a bouncy knitted star-patterned jumper which was Very Good.

Cult Hero Of The Episode: HOLY GUACAMOLE! Here we were, lazily going on about Brandon vs Wang, only for Brandon to have a relatively quiet one and literally the whole of Imperial coming out with all guns blazing. I think the whole series was a hustle for them – pretending that Brandon was the one to fear, and then BOOM! Brooks gets the first starter, McMeel gets several and they all confer utterly equally. Poor CCC didn’t know what had hit them; despite answering the film and music bonuses at the speed of light, it wasn’t enough to keep up. ‘You get three bonuses on physics,’ said Jez, and Imperial all looked so delighted. But goodness, this episode’s A-Lister was Captain Caleb Rich: he was all over the early bonuses, and bagged almost every starter going in the second half. He was like a quiet, deadly assassin disguised as a South London hipster, killing everyone with his knowledge of poison ivy, symphonic suites and postcolonial theory. I was AGOG.

Also, love this:

Wang & Brandon being shocked by Rich's buzzer #UniversityChallenge pic.twitter.com/W4CA0hNooA

Captain Rich now has an even more marvellous beard, making him look the absolute spit of avant-garde singer-songwriter David Thomas Broughton, and which you can fawn over on Bobby Seagull’s YouTube interview with the Fab Four here!

Handsome Person of the Episode: An even match between beaming Gunasekera of CCC and calmly impassive Captain Rich of Imperial, both wearing under-par shirts. Let’s give it Captain Rich, because he deserves everything today!

Horror Bonus Question: ‘Your bonuses are on experiments performed on board the International Space Station: the STPH5EHD experiment tested a cooling system in which cooling fluid is pumped without the need for fragile mechanical parts; for what sub-field of physics do the letters EHD stand for here?’

‘Electrohydrodynamics,’ said Andy, nonchalantly.

Regular Music Fail By Composition PhD-owning Composer, Kerry Andrew: ‘Your bonuses are on popular music in the irregular time of 7/4,’ said Jezter. ‘YASSSSS!’ trumpeted I, with a fist in the air. I got 2/3 because CCC’s Stewart is the sort of person who knows Peter Gabriel singles and I am not. Brubeck and Pink Floyd’s ‘Money’, phew, answered just about at the same time as Wang, ie in 0.0000023 seconds. Elsewhere, CCC’s Gunasekera was even faster with the tone poems. I got the Rimsky-Korsakov starter and the Mallarmé, hooray.

Dream Bonus Question Round: Crusades journey maps, 2/3! I have recently listened to a (much-recommended) You’re Dead to Me podcast, and the Eleanor of Aquitaine episode helped me out here. 2/3 in the Sight and Sound best ever films – was stoked to get Tokyo Story by Ozu.

STOP PRESS! I have just seen that Captain Wang, definitely the cineaste of the series, writes on film - here is an article of his in fabulous alt-culture bible The Quietus.

Jezza-Watch: Pretty nice again! I think he wore out all his insults on the Courtauld Institute of Art.

Bonus Trophy-Giving Feature: Andy and I had made a bet on who would appear to give away the (hideous) trophy in the always-awks ceremony at the end; I went with Mary Beard and he went with Simon Armitage. Instead, Jezzo introduced a tall, bland-looking chap called Andrew Wiles. ‘Who the fuck is that?’ I said. ‘Pttth,’ said Andy. But then we are rather humanities-biased. ‘They say maths is a young man’s game. I’d say University Challenge is a young man’s game,’ said Andrew Wiles. Hmm, yes, it does still seem that way, bruv.

The best thing of course is seeing what a) the bottom half of contestants looks like and b) how tall they are. Brooks is wearing well skinny jeans! Stewart’s huge, like a glossy champion horse! Brandon is teeny-tiny!

They underscored the ceremony with some slushy orchestral music, as if we were watching the end of a particularly weepy love story. Perhaps we were.

Kerry and Andy’s Score: 21, divided equally (we shouted ‘LEILA SLIMANI!’ at exactly the same time), or 105 points.

Brain Food: Leek and chard soup and salad

Tweets of the Day:

Please feel free to share, retweet, shout about this blog. I’m mostly a musician but a writer now too, and every little helps. And here’s me on Instagram.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

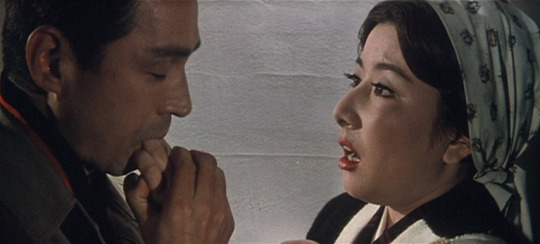

Jokyō (女経, A Woman’s Testament, 1960) by Kozaburo Yoshimura, Kon Ichikawa, Yasuzo Masumura

Jokyo is a 1960 Japanese anthology film, one of a few examples of this genre from the years of Golden Age of Japanese cinema. Three novels are shot by different directors Kozaburo Yoshimura, Kon Ichikawa, and Yasuzo Masumura and tied together by a theme of a strong woman who had discredited the men and learned not to trust them, under any circumstances.

The first story by Yoshimura depicts a female protagonist Kimi in quite an unpleasant light. She works in a club squeezing money from all the men approaching her. She excels in cynism and decayed moral. The motivation and background of Kimi played Ayako Wakao remain unclear causing no sympathy to her. Kimi is a sort of courtesan, and this is tribute Yoshimura pays to one of the most prominent themes of Japanese Golden Ages films. For instance, it has been one of the most significant themes for the acclaimed classic of Japanese cinema Kenji Mizuguchi. Ayako Wakao played a similar character in Mizuguchi’s final film Street of Shame. Though, in that film, her motivation was pretty much understandable. She’s been living with other geishas for years hoping to buy her way out of business. Very few women were able to do that, but Wakao’s character was shown very smart, emotionally stable and down-to-earth. Street of Shame was a poignant drama of geishas, while Yoshimura’s short film just tells heroine’s fiancée had dumped just before the wedding. So she ended up this way hating the men and thinking they are not worth any consideration and trust. It is certainly true in many situations, but Kimi doesn’t radiate anything positive. The viewers can express respect to her sense for business, but it is not quite clear why she ended up this way and why all the other women around are also shown to illustrate such way of interaction between men and women is the only thing that works out. Of course, 10 years back women in Japan had no chance to live the life as Wakao’s character lives so it’s a good thing she can be independent. But from the other hand, the entire idea is quite bleak, and at some point, it seems like director conveys that men always lie to women, and women are meant to scam them in return. And that’s about it, there is no alternative.

Even though I was not really fond of the first story, I must say Ayako Wakao always colours me amazed of her roles, and this case was no exception. She is one of the most outstanding leading ladies of the late Japanese Golden Age.

The second story shot by Kon Ichikawa brings a different tone. Kon Ichiwaka casts here another shining star of Japanese cinema of the 1950-s and one of his favourite actresses who collaborated with him several times – 1950 Miss Nippon Fujiko Yamamoto. In cinema industry, she’s primarily known for her role in Yasujiro Ozu’s Higanbana, but from my point of view in this film, she has one of her most stellar roles. Yamamoto portrays a woman agent tricking men into buying an expensive property. With elaborate decoys, she makes the men fall in love with her and convince them to help her buying the things belonging to her husband who passed away (though, the property belongs to the agencies she works for). In this story, she meets a writer who seemingly falls under her charm too and buys an almost rundown house for a huge amount of money. Later, the plot twists and the viewers come to know that the writer knew initially about the woman’s plan and decided to keep playing this game. A character portrayed by Yamamoto is adorable, mesmerizing, enthralling and tantalizingly enchanting. However, despite her nasty business she appears to be the type who just hasn’t met her love yet, but she is not as cynical as a character played by Ayako Wakao in the first novel. This story ends happily with the characters meeting each other and realizing they have nothing for each other, but joint affinity. The performance and emotions of one of the most beautiful Japanese actresses Fujiko Yamamoto make this story visually wonderful. Also, a short appearance of Hitomi Nozoe in one of her first roles in the cinema is very remarkable. She would get her spot of the top star of Japanese cinema later than the Golden Age faded away.

The third story is directed by Yasuzo Masumura. This novel stars a famous kabuki actor Ganjiro Nakamura famous for his roles in Ozu’s Floating Weeds, The End of Summer and many other famous Golden Age Japanese films. Also, it stars Rashomon’s star Machiko Kyo who played in a duo with Nakamura several times before this film. Machiko Kyo’s roles of the 1960-s are often even much impressive than her breakthrough performances of the early 1950-s. In Masumura’s novel, she plays a former geisha Omitsu who is currently a businesswoman. She has money now, yet she lacks happiness and emotional connections with people. As she gets older, she loses the hope to be happy with someone since she had learned the women should not trust men. This is what she tells her younger relative, a girl who intends to get married. Omitsu has been through many problems and social pressure during her life, and she tries to teach the young girl in a skeptical manner. However, in the end, she realizes that the young people are very vivid and passionate and they are supposed to experience ups and downs themselves. Eventually, she gives up agreeing to finance the future wedding and says one day she hopes to be happy in a family as well. The subplot with a schoolboy meeting an accident also helps her to soften her feelings and attitude. She is shown as a very experienced and strong woman who doesn’t interfere with the other lives, though. And I really liked this character Machiko Kyo plays in the story.

All-in-all, Jokyo tells three very different stories of women of a new Japanese generation who have been raised on the necessity to be strong and independent. This theme is crucial for the films of Japanese Golden Age of the 1950-1960-s as the social behaviour and roles of genders in social construct change radically in Japan at this time. This theme has been pivotal for Ozu, Mizoguchi, Mikio Naruse, Masaki Kobayashi and other famous Japanese masters of the Golden Age.

#jokyo#女経#kozaburo yoshimura#kon ichikawa#yasuzo masumura#Ayako Wakao#若尾 文子#fujiko yamamoto#山本 富士子#Machiko Kyo#京 マチ子#Ganjiro Nakamura#中村鴈治郎

8 notes

·

View notes