There are songs to sing, there are feelings to feel, there are thoughts to think. That makes three things, and you can’t do three things at the same time. The singing is easy, syrup in my mouth, and the thinking comes with the tune, so that leaves only the feelings. Am I right or am I right? I can sing the singing. I can think the thinking. But you’re not going to catch me feeling the feeling. No, sir.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The island is filled with the sounds of the sea. In Anglo-Saxon poetry, the metaphor of the ship was used as a token of movement and of composition itself, the narrative becoming a vessel which had to be driven across the face of the deep. The ship also became the frail form of the human being tossed on the ocean of life, with faith and hope and charity as its three anchors. King Alfred continually resorted to nautical imagery, and his own experience of the sea in peace and in war informs his writing; he declares, for example, that ‘a good steersman, by the raging of the sea, is aware of a great wind ere it come. He bids furl the sail and sometimes lower the mast, and let go the cables, and by making fast before the foul wind he takes measures against the storm.’ He uses many compound variants for the sea—egorstream, hronmere, laguflod, fifelstream, merestream—as if its reality could only be understood as shifting and multitudinous. It rises, too, in other Anglo-Saxon prose: in Byrhtferth’s invocation of ‘the salt sea-strand’, for example, and in Werferth’s description of ‘the person who approaches land in a frail ship’. In The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle we read of ‘the tossing waves, the gannet’s bath, the tumult of waters, the homeland of the whale’, this fervent litany calling up the spirit of the deep. The poetry of the sea is deeply implicated in the Anglo-Saxon imagination with its ‘sealte saestreamas ond swanrade’, the salt sea-currents which are the swans’ path, running into all subsequent English verse. The sea is also ‘calde waeter’ with lines which vary ‘the emphasis on the “depths” to “space” to “terror”’ suggesting the English fear of the ocean. In Anglo-Saxon poetry it is as if the island of Britain were truly the home or harbour. This in turn has informed the pastoral dream of England as a calm and tranquil haven. The exile or wanderer, in contrast, in customarily depicted as surrounded by ‘the sea booming—the ice-cold wave’.

Peter Ackroyd, Albion: The Origins of the English Imagination (2002)

#peter ackroyd#the sea#medievalisms#old english#psychogeography#england#of cabbages and kings#uploads

0 notes

Text

Louise Glück, from a poem titled "Fugue," featured in Averno: Poems, originally published in 2006

374 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Japanese Anemones and Michaelmas Daisies - Francis Hamel , 2009.

English , b.1963 -

Oil in linen. , 42 x 32 cm. 16.5 x 12.5 in.

352 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flatiron District, NYC.

Shot on Kodak Gold 200.

951 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Edward Alenius. Central Park Lake. 1937

693 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Hidden Beauty in the Mundane

Physicist Sidney Nagel has spent his career on topics that are somewhat unexpected: how coffee stains form, how droplets splash – or don’t, and how fluid flows into viscous fingers. Often this means looking at the mechanics of everyday occurrences that we otherwise take for granted. (Image credit: S. Nagel and K. Norman; via Quanta) Read the full article

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wayne Thiebaud - River Levee and Dock, 1966, oil on canvas, 30.5 x 25.1 cm

(christie's)

510 notes

·

View notes

Photo

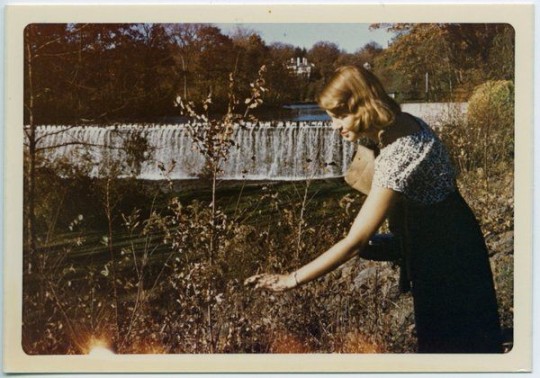

Sylvia Plath . Unkown photographer

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

jolie porcelaine | by porcelainehouse

7K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Orson Welles at the Mercury Theatre, 1938.

«Don’t give them what you think they want. Give them what they never thought was possible.»

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

““Is your novel an open work or not?” How should I know? That is your business, not mine. “With which of your characters do you identify?” For God’s sake, with whom does an author identify? With the adverbs, obviously.”

— Umberto Eco, Postscript to the Name of the Rose

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Decorative front cover of "Posson Jone'" and Père Raphaël by George W. Cable. Binding design by Margaret Armstrong.

Published 1909 by Copp, Clark Co.

Fisher - University of Toronto

archive.org

130 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nobuyoshi Araki / Sakura polaroids series, Tokyo

5K notes

·

View notes