Posts/ reblogs about the history of the Southeast Asian region (before the year 2000). The countries included in this definition are: Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, The Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Timor Leste, and Vietnam.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

“The Vietnamese people fully support the Palestinian people’s liberation movement and the struggle of the Arab peoples for the liberation of territories occupied by Israeli forces.” – Ho Chi Minh, North Vietnamese President, at the International Conference for the Support of Arab Peoples (1969). [x]

(1) Published by Arabs and Jews for a Democratic Palestine, c. 1970.

(2) Paul Thomas Chamberlain, The Global Offensive: The United States, the Palestine Liberation Organisation, and the Making of the Post Cold-War Order, 2012.

(3) 'Vietnam Passes the Banner of Victory to Palestine', published by the Palestine Liberation Organisation, 1972.

152 notes

·

View notes

Photo

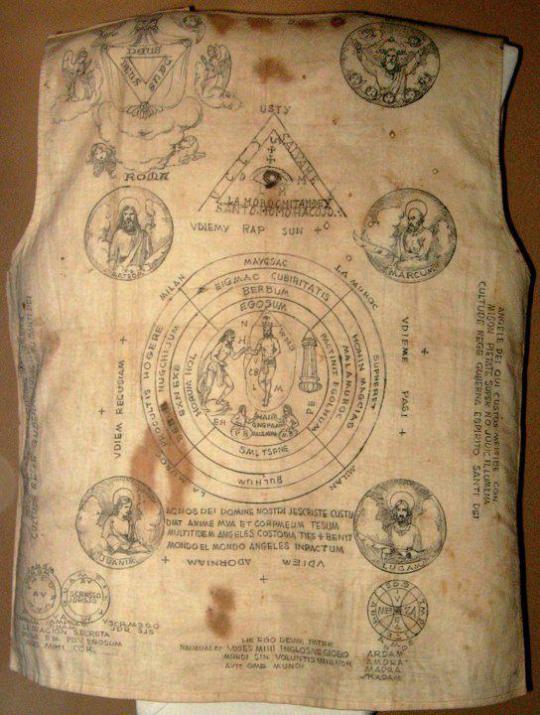

An “Agimat” (Talisman) Vest worn by a Filipino Revolutionary during the Philippine Revolution ca. late 1890s-early 1900s. Contains Folk-Catholic prayers in a Filipino peasant’s butchered Latin, and instructional diagrams on when or where the shirt would work. [544x720]

959 notes

·

View notes

Text

S. A. Ganapathy's date of birth is contested, with claims that he was born in 1912 refuted by a former colonial official who asserted that he was born in 1917. Ganapathy joined the Malayan Communist Party in 1939, fought with the Indian National Army during the Second World War, and was elected the President of the Pan Malayan Federation of Trade Unions in 1947, the first union party in Malaya and a significant threat to the British colonial powers that reoccupied the territory upon the end of the war. In 1949, in the midst of the Malayan Emergency, Ganapathy was charged with the illegal possession of a firearm (forbidden by Emergency laws) and sentenced to death by hanging. He was executed on 4 May 1949.

A. Ganapathy was a Malaysian milk trader who was arrested by Malaysian police in February 2021 to 'assist' them in their investigations of one of his brothers. While under police custody, he was repeatedly assaulted (with claims that the assaults included beatings with a rubber hose) necessitating the amputation of one of his legs and reports of kidney issues. Ganapathy passed away from his injuries in Selangor on 18 April 2021, leaving behind two children.

#malaya#malaysia#malayan emergency#trade unions#poetry#language and literature#you will never kill ganapathy.

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

To be clear, I don’t mean to hanker after a pre-national form of ‘Malayness’ that draws upon the rich cultural resources of the Nusantara. The desire to instead identify with some notional pan-Malay identity, and in solidarity with those based in Malaysia or Indonesia stems, I think, from some confusion as to what precisely happened when the Malayan project, of which Singapore was to partake in, failed. The door to a wider, expansive regionalism was firmly shut the moment Singapore formally separated from Malaysia and declared itself an independent country. Overnight, the Malays in Singapore found themselves reconfigured as one of four possible demographic groups. Singaporeanness, if once yoked to the Malayan project, now had to be recalibrated anew, and cruelly, as the story of migrants choosing to place roots, above planning the route for the journey onward. Smaller, transient journeys between islands became exercises in entering and leaving ports of entry. If colonialism first provided a mirror with which we could perceive some version of ourselves apparently unbroken by the line of history, Separation represented a clean, psychic break from the possibility of maturing that ‘Malayness’ with a regionalist bent. The Malays became, ironically, landlocked and had to once again adapt to significant cultural transformations—though all of this would be internal. Re-integration into the region was only possible after this new, multicultural Singaporeanness was formulated. In the preface of The Poetry of Singapore, Edwin Thumboo provided an overview of what was then a burgeoning Singaporeanness and its consequences for poetics on the island. He writes of the other communities feeling themselves adrift from their particular traditions, which were located elsewhere. For the Malays, he thought, not so much—the syair and other oral traditions were across the Causeway, but not really lost to geography like in the case of the Chinese and the Indians. He wrote, “the Malays apart, a sense of irrevocable belonging to place had yet to develop for a majority of the [other races]”. I think he was partially correct. The Malays in Singapore had slipped away from themselves in the present, and vanished, become strangely diasporic in their own homes. Maddeningly, the island and all surrounding islands remained firmly in place.

Hamid Roslan, Saya Orang Dibawah Angin, 2021

#singapore#malay identity#nusantara#southeast asia: as a region#archipelagic thought#national identity

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"But what selfhood was to be determined in the Indies? What were its common ties, and where did its boundaries lie?

Leaders voiced very different ‘nations of intent’. The rallying cry of Ernest Douwes Dekker before the war, of the Indies for the Indier, suddenly lost force. The word ‘Indies’ too closely evoked both British India and the Dutch state, as did its variant, Insulinde . Some preferred the term Nusantara, literally the ‘islands within’ or ‘between’. It broke with the linguistic inheritance of Dutch; it was archipelagic in compass. But its origins lay in a chronicle of the world-conqueror from fourteenth-century Majapahit, Gajah Mada, and this made it too Java-centric for nationalists from the outer islands. The term ‘Indonesia’ had been used by early British ethnographers and then by some Dutch scholars at Leiden University to designate a wider cultural region of island Southeast Asia. Suddenly it began to acquire imaginative force. In late 1917 the exile Soewardi and others established an ‘Indonesian Association of Students’ at Leiden. Some of its members were Dutch, such as the Semarang-born H. J. van Mook, who had attended the same Surabaya high school as Sukarno, where his father taught. Men like van Mook expected to participate in and to lead an ‘Indonesia’, but they did not yet see it as a nation. Others saw ‘Indonesia’ as a common destiny of the island peoples, in the struggle for which Europeans, Eurasians, Chinese and Arabs might be allies but not full members. But there was also a claim for a more equal belonging, where, in Soewardi’s phrase, ‘whoever is a citizen of the Indonesian state is also an Indonesian’. The question of the new nation’s ethnic and cultural foundations remained unresolved and untested in the Indies itself."

Underground Asia, Tim Harper.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

This notebook, “The Rainforest Speaks: Reimagining the Malayan Emergency,” gathers writers, translators, filmmakers, artists, historians, and critics to revisit a significant period of Southeast Asian history—the Malayan Emergency. The Emergency, which took place from 1948 to 1960, was a war between British colonial forces and communist fighters mostly based in the Malayan rainforest. The history and analysis of this war—including British initiatives that forcibly resettled half a million people, primarily ethnic Chinese Malayans, into heavily surveilled New Villages, and deported thousands to China—is fragmented and complex. Not only is the history split across different languages such as Malay, Chinese, and English, it is often eclipsed by the British colonial depiction of the fight as an “emergency” incited by communist “terrorists,” instead of an anti-colonial struggle.

The writers featured in “The Rainforest Speaks,” edited by Min Ke (民客), attempt to recover this elusive past and address those not well-represented in the historical record, including the communist guerrilla fighters, rural Chinese Malayans, Indian plantation workers, the indigenous Orang Asli people, and the rainforest itself. The contributors, who Min Ke notes are “all a generation or more removed from the events of the Emergency,” contend with these gaps through original translated stories, essays, criticism, and art. The resulting collection of work resists a singular narrative about the Emergency and instead traces the many perspectives of those involved. “The urge to return to scenes of the Emergency, to look beyond the colonial archive, is not only a painstaking task of recording imperial wrongs that persist in the present,” writes Min Ke in the editor’s note to the notebook. “It is, above all, an imaginative task, one that cannot be captured by an individual or group.”

Each piece in “The Rainforest Speaks” features art by Sim Chi Yin.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The conceptualization of Southeast Asia as a coherent region and episteme was born of local anticolonial regional collaboration; World War II military objectives; Japanese imperialism; Chinese and Japanese studies of nanyang and nan’yō (South Seas), respectively; and the post–World War II U.S. academy that invested heavily in area specialists. Postwar area studies academics later identified persistent shared traits to justify their discipline and the categorization of Southeast Asia as a single region: bilateral kinship, high levels of female autonomy, leadership by “men of prowess,” a concept of animating “soul stuff,” spirit propitiation, houses resting on poles, and a rice-fish diet."

Asian Place, Filipino Nation: A Global Intellectual History of the Philippine Revolution, 1887-1912, Nicole CuUnjieng Aboitz, 2020.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

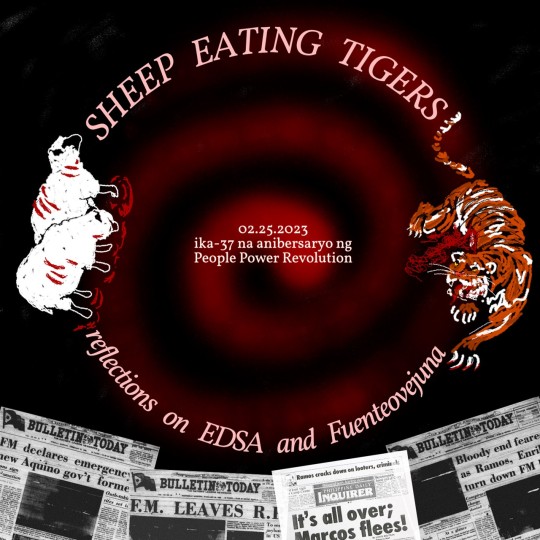

Sheep Eating Tigers: reflections on EDSA and Fuenteovejuna

[ID: a 15 page comic.

Page 1: Sheep Eating Tigers: reflections on EDSA and Fuenteovejuna. 02.25.2023, ika-37 na anibersaryo ng People Power Revolution. The words are in circular form, with illustrations of wounded sheep licking at blood and a tiger with its intestines out surrounding the text. A spiral serves as the backdrop. Several newspapers detailing the EDSA revolution are placed on the bottom of the image.

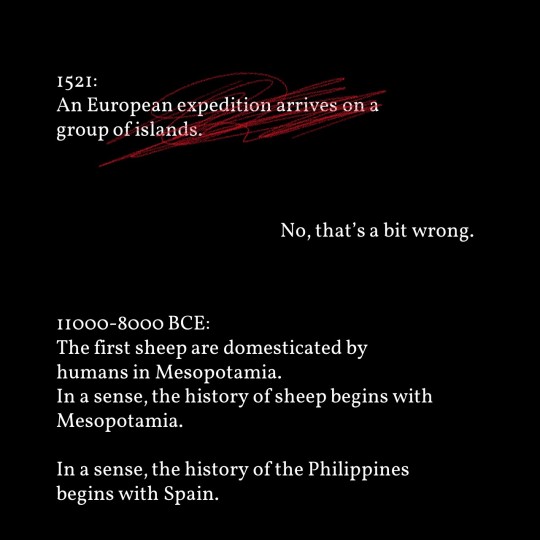

Page 2: 1521: An European expedition arrives on a group of islands. (This line is crossed out) No that’s a bit wrong. 11000-8000 BCE: The first sheep are domesticated by humans in Mesopotamia. In a sense, the history of sheep begins with Mesopotamia. In a sense, the history of the Philippines begins with Spain.

Page 3: Over time sheep are bred and traded over large swathes of land to address a number of human needs: meat, milk, wool, skin, sacrifice. (A sheep skull is in the background) 6000-1000 BCE: Sheep are introduced and bred in Europe. Spain becomes particularly wealthy from the production and trade of merino wool.

Page 4: Some facts about domesticated sheep (Ovis aries): (what follows are screenshots from Wikipedia) Sheep are herbivorous animals sheep have a strong tendency to follow frequently thought of as unintelligent animals however, sheep are usually silent in pain peripheral vision may be greatly reduced by “wool blindness” little ability to defend themselves

Page 5: The image is text interspersed with Wikipedia screenshots. More facts about domesticated sheep (Ovis aries) Followers of Christianity are often referred to as a flock, with Christ as the Good Shepherd. 1521: An European expedition arrives on a group of islands. Christianity is introduced to what we now call the Philippines. little ability to defend themselves 1521: Ferdinand Magellan attacks Lapulapu’s forces in a gesture of superiority (this is slashed) goodwill to Datu Zula. He is killed. Domestic sheep provide a wide array of raw materials 1564-1898: Spanish colonial era in the Philippines. Agriculture in the Philippines is used to supply tobacco, sugar, abaca, etc. for use and trade, most notably in the Manila-Acapulco Galleon trade.

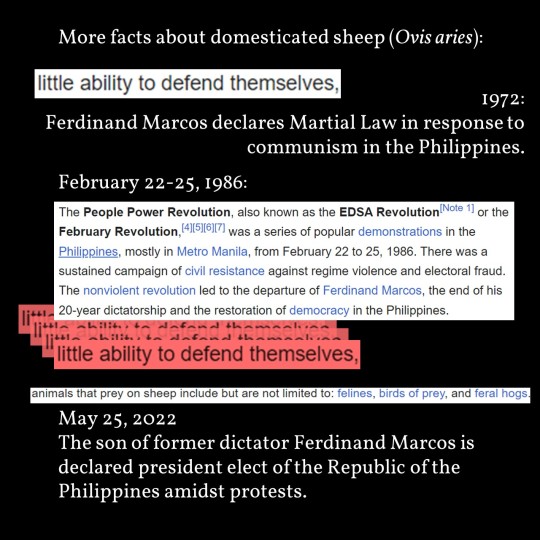

Page 6: 1580 - 1681: Siglo de Oro or, the Spanish Golden Age of Baroque Literature. More facts about domesticated sheep (Ovis aries): little ability to defend themselves 1972: Ferdinand Marcos declares Martial Law in response to communism in the Philippines. Marks the period of the Philippine “Golden Age” and the “Tiger Economy”.

Page 7: More facts about domesticated sheep (Ovis aries): Sheep themselves may be a medium of trade in barter economies August 1898: The Treaty of Paris is signed by the Spanish and US governments, transferring ownership of some Spanish territories, including the Philippines, to the US. This marks the beginning of the American colonial era. In the English language, to call someone a sheep or ovine may allude that they are timid and easily led. December, 1898: A policy of “benevolent assimilation” is declared, putting the Philippines under American governance.

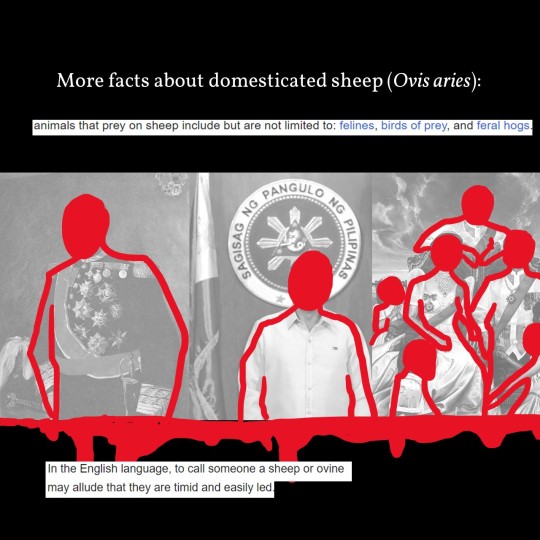

Page 8: More facts about domesticated sheep (Ovis aries): animals that prey on sheep include but are not limited to: felines, birds of prey, and feral hogs. Three images of a governor general, a president, and a family portrait follow, faces covered by red dots and figures outlined in red. A screenshot also reads “In the English language, to call someone a sheep or ovine may allude that they are timid and easily led.”

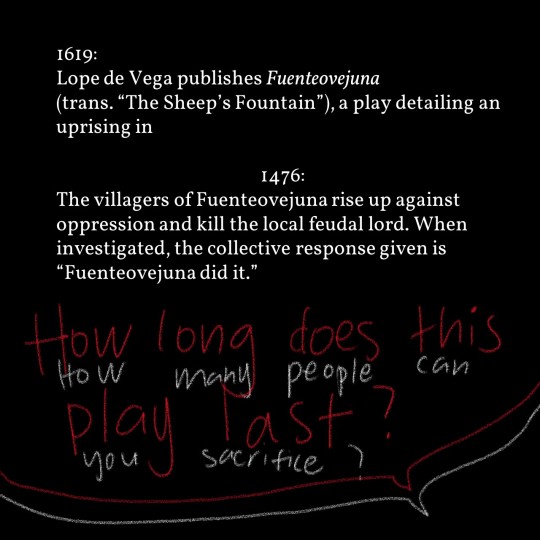

Page 9: 1619: Lope de Vega publishes Fuenteovejuna (trans. “The Sheep’s Fountain”), a play detailing an uprising in 1476: The villagers of Fuenteovejuna rise up against oppression and kill the local feudal lord. When investigated, the collective response given is “Fuenteovejuna did it.” February 22-25, 1986 “The People Power Revolution, also known as the EDSA Revolution or the February Revolution, was a series of popular demonstrations in the Philippines, mostly in Metro Manila, from February 22 to 25, 1986. There was a sustained campaign of civil resistance against regime violence and electoral fraud. The nonviolent revolution led to the departure of Ferdinand Marcos, the end of his 20-year dictatorship and the restoration of democracy in the Philippines.” Below the snippet, the line “little ability to defend themselves” is repeated.

Page 10: The two previous snippets on Fuenteovejuna is repeated. January 17-20 2001 The Second EDSA Revolution, also known as the Second People Power Revolution, EDSA 2001, or EDSA II (pronounced EDSA Two or EDSA Dos), was a political protest from January 17–20, 2001 which peacefully overthrew the government of Joseph Estrada, the thirteenth president of the Philippines. Following allegations of corruption against Estrada and his subsequent investigation by Congress, impeachment proceedings against the president were opened on January 16. The decision by several senators not to examine a letter which would purportedly prove Estrada’s guilt sparked large protests at the EDSA Shrine in Metro Manila, and calls for Estrada’s resignation. Below the snippet, the line “little ability to defend themselves” is repeated

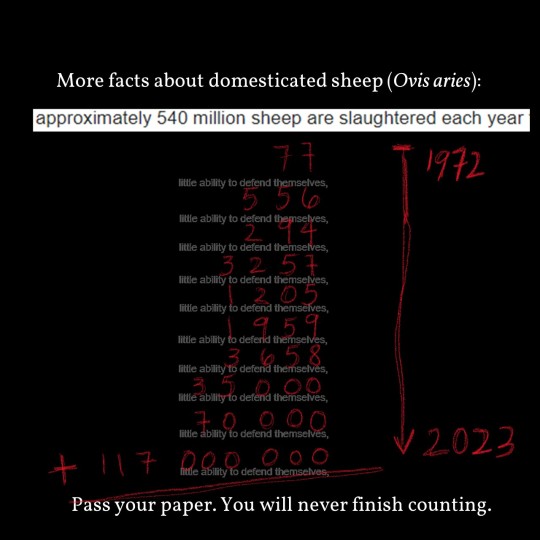

Page 11: More facts about domesticated sheep (Ovis aries): Approximately 540 million sheep are slaughtered each year. A sum from 1972 to 2023 follows, interspersed with the line “little ability to defend themselves”. The numbers are: 77, 556, 294, 3257, 1205, 1959, 3658, 35000, 70000, 117000000. A line reads “Pass your paper. You will never finish counting.”

Page 12: More facts about domesticated sheep (Ovis aries): little ability to defend themselves 1972: Ferdinand Marcos declares Martial Law in response to communism in the Philippines. February 22-25, 1986: The People Power Revolution, also known as the EDSA Revolution or the February Revolution, was a series of popular demonstrations in the Philippines, mostly in Metro Manila, from February 22 to 25, 1986. There was a sustained campaign of civil resistance against regime violence and electoral fraud. The nonviolent revolution led to the departure of Ferdinand Marcos, the end of his 20-year dictatorship and the restoration of democracy in the Philippines. The line “little ability to defend themselves is repeated. animals that prey on sheep include but are not limited to: felines, birds of prey, and feral hogs. May 25, 2022 The son of former dictator Ferdinand Marcos is declared president elect of the Republic of the Philippines amidst protests.

Page 13: 1619: Lope de Vega publishes Fuenteovejuna (trans. “The Sheep’s Fountain”), a play detailing an uprising in 1476: The villagers of Fuenteovejuna rise up against oppression and kill the local feudal lord. When investigated, the collective response given is “Fuenteovejuna did it.” Below, two handwritten speech text: How long does this play last? How many people can you sacrifice?

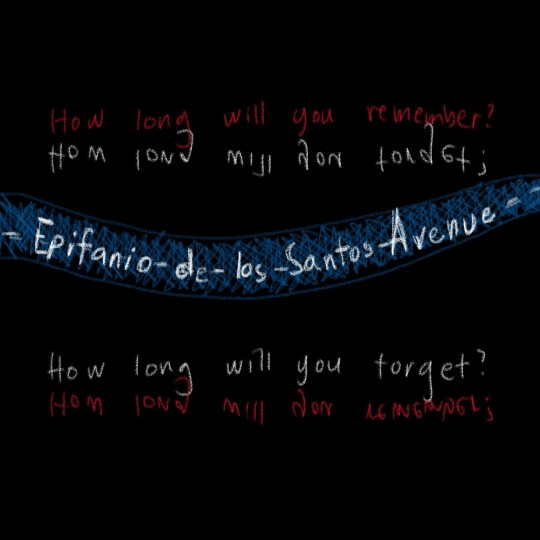

Page 14: Handwritten: How long will you remember? is reflected by How long will you forget? A road with the name Epifanio de los Santos Avenue is drawn below. Below both is another handwritten text: How long will you forget? reflected by How long will you remember?

Page 15: Text: Based on your reading of Isaiah 11:6, heaven is paradise for? A handwritten note reads: Tick only one. Three checkboxes follow, one for sheep, one for tiger, one for the one who eats. Pen marks dot the checkboxes. Text under reads “Pass your paper. The play is about to start.” The artist signature is in the corner. /end ID]

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

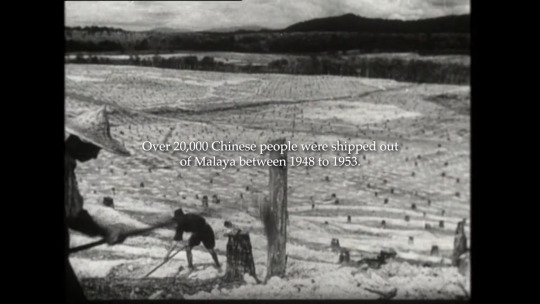

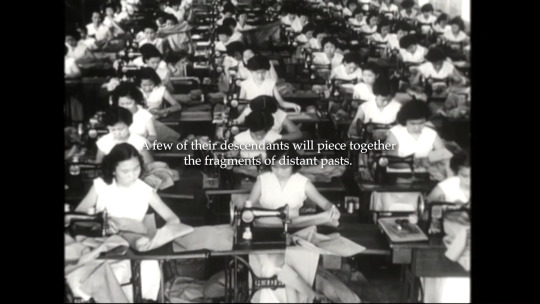

Chinese Go Home, a film by historian Rachel Leow (2021); 18:33 runtime.

Available for free viewing here.

Between 1948 and 1953, over 20,000 Chinese people were deported from what was then British Malaya to China. Both the countries they were leaving and going to were embroiled in war and revolution. "Chinese Go Home" tells the story of this extraordinarily complex historical moment through the voices of two women whose families were sundered in its aftermath.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Songs We Sang, dir. Eva Tang, 2015, Singapore.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

youtube

At its best, phleng phuea chiwit (เพลงเพื่อชีวิต, translated as songs for life) is a genre of music that communicates the immense perseverance of the working-class in the face of continued oppression. A genre of music that champions the rights of the working-class with songs that inspire solidarity.

[...]

The origins of phleng phuea chiwit can be traced back to the 1970s during the popular movement preempting the October 1973 uprising. The popular music of the day, luk thung, featured troupes of dancers, loud instruments, and extravagant stage shows. It was born from the era of social engineering perpetuated by Phibunsongkhram. Students criticized the genre and did not see it as a viable form of protest music. Thus, phleng phuea chiwit was born.

‘“When I was young I listened to Luk Thung, but I was looking for something else. We wanted to shout at the government. Luk Thung lyrics did not deal with serious issues.” – Nga Caravan (Vater, 2003).

The songs of phleng phuea chiwit were influenced by the aforementioned genres, as well as Isaan melodies and the prominent folk music scene in America (e.g. Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and Pete Seeger). Inspired by Jitt Phumisak and his ‘Art for Life’ ideology, the songs were criticisms of social hierarchies, imperialism, and championed the rights of laborers, farmers, and the rest of the working-class.

It was student activists that formed many of the genre’s bands; Caravan was formed by student activists (Surachai Jantimathawn (Nga Caravan) and Wirasak Sunthawnsi) from Ramkhamhaeng University. The period from 1973 to 1976 is when Caravan and other phleng phuea chiwit artists enjoyed their first peak in popularity. It was the October 6 1976 massacre and subsequent coup that forced Thai communists (including Caravan and many other phleng phuea chiwit artists) to flee into hiding.

While in hiding, artists and students were responsible for writing and recording communist propaganda (e.g. Ramwong neung thanwa and Ramwong su rop).

The communist insurgency began to decline with PM Prem Tinsulanonda’s amnesty in 1980. Over the following years more and more CPT members, students, artists, and others in hiding began to return to the public sphere. Caravan began releasing albums again, and in a move that echoed their Western counterparts, soon went electric.

Music for Life - Revisited

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Whether sung in Sanskrit or in Vietnamese, or played on renêt or modern violin, '…music in Southeast Asia is dominated by a well-integrated, highly cultivated style which is characteristic of the whole area.' This collection of Music of Southeast Asia features both the popular and traditional music of Myanmar, Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand, China and Laos and captures the influence, and in certain cases the rejection, of the Western musical tradition on the music of this region."

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Over the week that we spend in Bali, Pak Arwen, the minivan driver, becomes friendly with my father. This happens because they are both Indonesian-Chinese – which is to say that they share a shiver down the spine regarding certain historical dates, political figures and tribalist slurs.

At some point, when it became too difficult to be Chinese in Sumatra, each man's family gambled the present for its future. My father's fled for Singapore and Pak Arwen's for Bali. Decades later, the two men occupy different stations in life: my father plays a tuan to Pak Arwen's supir. But their shared memory of this gamble – and the conditions that forced it – levels the playing field a little.

Both men, being Christian-Chinese, have lived the parable about the pillar of salt. They understand the importance of moving forward, eyes fixed to the line on the horizon.

Is Pak Arwen looking forward or backward when he tells us: This is too much? He says this as we drive past a large banner, stirring in the breeze by the side of the road. The banner is bright red, with a slogan in block capitals: TOLAK REKLAMASI TELUK BENOA. Resist the reclamation of Benoa Bay.

This is one of the first non-English signs that we've seen all day, which makes me think that it's not for tourists. Or perhaps it's for a specific kind of tourist – the kind that's stayed here long enough to perceive that something isn't on offer to them, and want a part in it anyway.

My father asks: What do you mean?

And Pak Arwen responds, one hand circling the steering wheel for eloquence: Nothing is good enough here. Roads, land, water…

The road in front of us is marked by potholes; the banner speaks of land problems. What about water? I sprint through some figures: say there are 5,000 hotels here plus hundreds of unregistered villas, and each one has a pool…

I think about the news stories that I have read, on The Jakarta Post and Al Jazeera. Impossible to describe how much of this island's water goes into making, and maintaining, glamour. Each week, scores of foreign developers reach into Bali's south coast, summoning up yoga studios and restaurants by the dozen. Trump shakes hands with Harry Tanoe and a golfer's empire materialises, sun-bleached and thirsty by the gallon.

But all this diverts water from the poorer North, where most locals live. In this land of glassy infinity pools, more than half the rivers have already run dry. Streams still criss-cross the terraced rice fields of Ubud. But deeper underground, the freshwater banks are pulling back from parched earth. Bali's farmers live the reality that its tourists cannot see – at night, they sleep in their fields with one eye open for irrigation thieves.

Later, I root around online for more stories about Benoa Bay. I learn that Tommy Winata, the Indonesian billionaire, is trying to reclaim land there. He wants to coax hectares of malls, theme parks and an F1 track out of swampland. But this floating world will crush the coral reefs that protect Bali's coastline and keep the sea at bay. Eventually it will flood the island, dragging whole villages into the sea.

In a place like Bali – I tell myself – the supply of pleasure must always meet the demand for it. Even if it costs the future for some people; even if it means death.

After all this is paradise, where nothing ever runs out.

.

Let me tell you another story about Bali that I know. This one is a creation story, concerning the beginnings of paradise.

Imagine that the year is 1906. Bali is an island divided. Dutch forces have occupied the northern territories, leaving three Hindu kingdoms where once there were six. Today, they begin the march south to complete their reign, winding downwards from Tabanan to Badung to the offshore court of Klungkung.

This story is an old one, whose basic tenets are familiar to many people around the world. At heart, it is a story about mismatched means and ends: guns versus kris, ambition versus ancestral claims.

The Dutch troops begin their journey. Quickly, they pass through the city of Kesiman to reach their first stop, Denpasar. At first, the city streets seem too quiet: where is the resistance that they come ready to meet? But as the soldiers advance, they hear something stirring in the distance, from the direction of Denpasar palace: the faint but unmistakable pulse of drums.

And so they go on. As they near the palace, a procession of silent figures files out from its gates. From a distance, they spy the Raja on his palanquin surrounded by courtiers and priests, wives and guards, and children and servants. There are hundreds of people now, robed in white with dusty feet. Flowers laced into their hair.

Both parties, the Dutch and the Balinese, advance. Now there are 200 paces between them; now, 100. The gap between two worlds is narrowing. Then it closes for the century to come, and possibly forever: a puputan commences. The Raja steps down from his palanquin and gives a signal. Instantly someone lunges forward and knifes him in the chest. Motion erupts across the landscape as men force weapons into their children, then stab themselves. Women fling jewels into the air and then topple, wailing, onto their knives.

Dark liquid starts to fill the ground. A metallic scent rises. But Balinese people keep emerging from the palace in a slow, unstoppable stream. When they're within sight of the Dutch troops, they plunge forward onto their daggers, then collapse into the growing snarl of limbs.

Their bodies cover the ground, both protest and decree.

By this point the Dutch soldiers have opened fire, then ceased fire, then opened fire again. They don't know what to do. Several centuries of colonial rule have left them untrained for situations involving consent – and this seems like more than consent, seems close to an invitation. Eventually, they resort to doing what they know best – which is to seize what isn't on offer, looting the corpses for anything that gleams through the sticky mess of fluids.

There will be two more puputans before Bali falls completely, both of them photographed. Eventually, these pictures will cause a kind of moral backlash in Europe, with the thumping of Bibles and pontifical braying. Desperate to hold on to their empire, the Dutch will announce a new resolution: from now on, they will protect Balinese culture and not gun it down. In fact, they resolve to protect Balinese culture so soundly that it never changes from its present state or experiences the advancements of modern life.

Let the world move slowly here, their edicts declare. Progress is not for the pure of heart. Which is what the Balinese people are, presumably – puputans notwithstanding.

For decades to come, Dutch laws will force the Balinese people to wear Baju Endek and not linen pants – to converse in local dialects and not Malay, the regional code of rebellion. All over the island, atap roofs will sprout over modern innovations in galvanised iron. Whole dances will be invented for the Balinese people to perfect, then unleash upon large groups of tourists.

Soon, these tourists will be everywhere, scouring the island with their notepads at the ready – fresh from the war in Europe, and hungry for visions of innocence. Look at this place, they'll say, pointing at random to rice fields and bare-chested women. What authentic culture; what happy natives! So simple and contented with their lot.

They'll forget about the puputans, the cold carpet of bodies.

Bali becomes a paradise on earth.

Island Paradise, Tjoa Shze Hui

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpts from The Jakarta Method, Vincent Bevins

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

There are many stories of how this song came to Nusantara. One of them goes: there was a regular steamer service between the Seychelles and Singapore. One of them goes: the daughters of the exiled Sultan heard the song on Mahé and loved it, and taught it to their brother, who taught it to another brother, who whistled it to a British administrator, who made it Perak’s state anthem. One of them goes: this happened in 1888. One of them goes: this happened in 1902. One of them goes: the whistler was in fact the private secretary to another Sultan, a musician himself. One of them goes: the tune was already popular in Perak, which is why it was whistled. One of them goes: the Sultan in exile composed it himself. One of them goes: the Sultan, returning from exile, was required to live in Singapore, and heard the tune there. One of them goes: this happened in 1901. One of them goes: more than one story can be true. One of them goes: it is pure coincidence that two songs have the same tune, inilah yang dikata seni muzik itu sejagat, this is why it is said the art of music is universal.

[...]

What was gained by turning “La Rosalie” into the official anthem of Perak, and then Malaysia? Certainly these two versions are more confident, more rousing and unifying in their attempts to bring Negeri, and then Negara together. The imaginative boundaries of the song seem to have expanded from a passionate lover or sibling to all the people of a state and a nation. With the expansion comes a corresponding narrowing too. The rain on Rosalie’s back, the moon, golden sand, the falling flower of a slain sister, a pair in a rowboat, again the moon, the audacity of swearing upon a crocodile are all swept away by grand orchestral arrangements. Instead of revenge, or pining, or a heart that cannot have any peace, there is harmony between people, ruler, land and God, at least in the lyrics.

[...]

—when it was first announced to the public, it was thought of as undignified, after all, the tune coursed through every jukebox, every dancehall—

—a Cantonese one, too, but the lyrics are so sickly sentimental, barely saved by the language—

—all other versions banned by statute—

—the union's response to the synthesiser was to try to ban it, because it put string players out of work—

—made his breakthrough while at university in Taiwan… calls for his citizenship to be revoked… considered charging him with sedition—

—the idea began sprouting in Iowa, but my first draft was ignored by the editors of a local publication, so I shelved—

—Tan Sri Dato Abdul Mubin Sheppard, born Irish, joined the Malayan Civil Services, married in Singapore, imprisoned during World War II, converted to Islam the year of Malaysian independence, performed the Haj, documented several accounts of our tune, died Malay—

—accusations of plagiarism fly furiously all over the internet, each comment a little flea—

—but there are no records of it in de Béranger’s extant published songs, and he wasn’t a composer anyhow, but a lyricist, so who could have written the tune—

—in Dutch it seems to have been about a slavegirl pining for her master, who has sailed off leaving her with a blue-eyed child—

—Saidah Rastam, who I am in debt to, says, my country is an emotion… When the Federation of Malaya was born, hardly anyone knew what Malaya should be. There were so many desires, conflicting beliefs. It could all have fallen apart so easily—

—Sheppard had the sense of adventure to send the anthem to the Seychelles in the 1960s, and an old woman recognised it instantly on the radio—

—video of schoolkids singing the anthem in Chinese translation went viral; investigations found Chinese textbooks with the offending versions and unearthed Tamil ones too, except the Tamil text is sung phonetically, based on the Bahasa Malaysia—

—my peer reviewer said “Terang Boelan” was one of numerous cultural texts that propelled the Japanese fascination with and longing for “the South” before and during the Second World War—

—ruled that the Chagos Islands have to be returned to Mauritius, but the UK says it has every right to them, and so the Chagossians keep waiting—

—a malaise called time is upon us all, and it makes us forget—

—also performed by Felix Mendelssohn's Hawaiian Serenaders, Mamula is, as far I as I can tell, an imaginary island, as imaginary as Sawoba, itself as beautiful as Hawaii—

—Wayang Kassim made it a hit from Penang to Singapore and beyond—

—there might have been a lyric-writing competition forgotten or obscured by the official narrative, with Indonesian-Malaysian composer and musician Saiful Bahri winning and writing the words to the anthem—

—isn’t there something in the silver voice, the grey ship, the tin—

—it could all have fallen apart so easily, the miracle is, it didn’t—

—hum it, now, all together, take a deep breath, and—

A History of Negaraku in Seven Rumours, Tse Hao Guang

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Perhaps the Emergency may be envisioned in sites of memory, infusing material objects—texts, monuments and moments of silence—with the will to remember. “We speak so much of memory because there is so little of it left,” Pierre Nora (7) writes. Perhaps misleadingly, he reduces memory into archival form, a “gigantic and breathtaking storehouse of a material stock of what it would be impossible for us to remember” (13). Even more than the solemn heights of the National Monument, perhaps the Emergency’s most salient sites may derive from the besieged police station at Bukit Kepong. A diorama of the officers killed defending their posts against guerrillas stands at the Royal Malaysian Police Museum; the incident is refought in film, literature and the syllabus, each of them also circulating the binary logic of race. Perhaps it would be better for us to think of memory as being multidirectional—as being knotted, rather than as distinct sites—a notion which “cuts across genres, national contexts, periods, and cultural traditions” (Rothberg 18). To transcend the limited imagination of the nation-state and a forgetting of the effects of empire on the periphery. Thus Bukit Kepong can be remembered together in our collective memory with the dying volunteers at Imphal, the jungle trials, Singapore’s 1964 riots, the massacres at Thammasat University or on the islands of post-Konfrontasi Indonesia, all cast together in the long shadow of (de)colonisation. [3]

[...]

Sir Robert Thompson, supposedly the greatest mind in counterinsurgency operations, exported Malayan tactics to the South Vietnamese, including the forced resettlements (Beckett 41). A sort of military memory was being exercised, a lineage which began with the British in South Africa; later the Americans resettled the Filipinos rebelling against unwanted occupation into “suburb[s] of hell”, and such camps became “a tool in the arsenal of nearly every country” as they took on horrific iterations (Pitzer and the Zócalo Public Square). Systematic containment extended to refugees—Sir Robert’s strategies could not stop the arrival of the so-called “boat people”, and sites such as Pulau Bidong became notorious, which—if I recall correctly, but I’m an unreliable narrator—a former supervisor of mine once spent time in. Their general malaise permeated literary memory—an unnamed Malaysian camp was described at length in Kim Thúy’s Ru, her novel another campaign in what Viet Thanh Nguyen describes as the perpetuation of “war memories through art, literature, cinema, photography, memorials, and museums” (144). But memories of containment and fixed boundaries are an aberration in a region where kingdoms and states were once defined by connectivity. Sultan Mansur, in a fifteenth-century correspondence with the King of Ryukyu extolling the virtues of maritime commerce, declared how: “All the lands within the seas are united in one body, and all living things are nurtured in love; life has never been so affluent in preceding generations as it is today” (cloud projects). Perhaps this flux gave rise to the word “merantau”, which Wang Gungwu latched upon as a more encompassing term than its English equivalent, considering that:

the technical use of the word ‘migration’ […] recognises that there are really two distinct acts involved in most human migrations, first to migrate or move from one place to another and then to decide to stay and not return home. The act of migration in itself is normally an incomplete and indecisive one. (Wang 169)

This seems a kinder understanding, one that allows for a U-turn, when memory gives way to imagining a future. There is comfort knowing that the future, much like the past, is not necessarily permanently counted in generations, doomed to repeating the narrative of foreignness. [7]

Memory of the Left, William Tham Wai Liang

#southeast asia: as a region#malaysia#the philippines#indonesia#thailand#vietnam#literature#emergency

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two poems in translation from Malay by the late Malaysian writer, Usman Awang.

Greetings to the Continent

I

They separate us the passports visas frontiers all names for barriers they rob us with their laws sending bullets wrapped in dollars forcing us to choose and choose we must there is no other way

II

Friend, you have chosen guns and bullets many leaders prefer their dollars for this you must soak your clothes red grass, red river children’s weeping the blood of the exploited

III

You squeeze cactus and grind stones to make food and drink girls toil decorated in dust little children sling on their weapons you darken the sky with exploding pipelines others sing in prisons for the freedom of Palestine

IV

We strive in drying rice fields daring peasants have begun to clear the virgin jungle small beginnings in a cloudlike calmness a calmness that nips us in the bud we the few are still learning from all your experiences, and our own

we shall consolidate the May eclipse at the true target of this archipelago

V

Greetings without visa passport gulf colour to humanity, people, of all continents.

1970

(Translated by Muhammed Hj Salleh)

Beloved

I'll twine the froth of the sea into a rope to tie you

I'll weave the waves into a carpet for your bedchamber

I'll spin the clouds into a veil for your hair

I'll sew the mountain clouds into a nightgown for you

I'll pluck the star of the East a brooch to sparkle on your breast

I'll bring down the darkened moon a lamp to light my desire

I'll sink the sun embrace your seas of night drink your crystals of honey

My beloved how many dreams murder reality with illusions of heaven

1971

(from Cempaka: An Anthology, published by Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka (DBP) in 1992)

10 notes

·

View notes