Scattered thoughts on FromSoftware's fantasy action RPGs. Updates irregularly. Enjoy!

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

So today I learned that you can hear Gwyndolin begging for help while being cannibalized by Aldrich if you stand next to the walls of his room before his boss fight. Miyazaki wtf

Added the transcript because it’s kind of hard to make out

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

[first day as a woman in a fromsoft game] go, then. And carry mine tidings with you. Let the hope I hold for you carry you into the dark. *waits until the player is gone* okay jesus christ my feet are fucking freezing you sure I can’t wear some socks in here

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

"To be realistic, I feel something beautiful needs something ugly — something that's depraved or tragic to heighten and embolden that beauty. I think that's a much more realistic depiction of beauty, to have something small and beautiful inside something tragic and decaying. Something that's just plainly, outwardly always beautiful doesn't have a sense of reality to me." — (Hidetaka Miyazaki)

"I remember when I was drawing the Undead Dragon, I submitted a design draft that depicted a dragon swarming with maggots and other gross things. Miyazaki handed it back to me saying, 'This isn't dignified. Don't rely on the gross factor to portray an undead dragon. Can't you instead try to convey the deep sorrow of a magnificent beast doomed to a slow and possibly endless descent into ruin?'" — (Masanori Waragai)

774 notes

·

View notes

Text

Something that I've been anticipating lately is a renewed appreciation for, FromSoftware's post-King's Field "medievalist" releases which de-emphasize speed and spectacle; that is, Demon's Souls, Dark Souls, and Dark Souls 2.

I'm a little surprised that there hasn't been much commentary on the gradually diverging artistic shift we can track from Demon's Souls to Elden Ring. Mostly, the discursive possibilities have been limited to remarking upon whether or not Elden Ring is "too hard" relative to some earlier title. This focus on design has tended to occlude observations on the aesthetic consequences of a divergence.

In a variety of ways, Elden Ring is not only (in an abstract, although probably very often also in an actual, sense) a much harder game than Demon's Souls; it also represents something of the upper limit of a type of grandiosity of combative expression, whether that has to do with a boss' design or the capabilities of our avatar. Were we to be dismissive, and maybe a little culturally reductive, we could use the term "anime" for critical shorthand when describing how one of Shadow of the Erdtree's bosses has a magical sword attack that encompasses the entire space of a fairly large arena.

On the one hand, Elden Ring represents a sensible evolutionary point of a mechanical foundation established by Demon's Souls. On the other hand, Rellana's courtyard-sweeping attack, and other things, like very nearly anything to do with the second phase of the DLC's final boss, are the sort of stuff I joked about as an inevitability after finishing Dark Souls 3's DLC. Pretty much any major opponent from Dark Souls and its sequel seems like a quaint, jerky windup toy when compared to Elden Ring's bosses.

I wonder, though, if that relative restrictiveness won't come to be newly valued for the differentiation it represents internally to these games -- perhaps most visibly with Dark Souls 2, which not too soon after its release, and ever since, has tended to be spoken of as an outcast in need of either a dunking or a defense, or has confused people obsessed with ranking their media diet. It's highly unusual that Dark Souls 2's development team would decide to make a game which is more slow and methodical than its two forebears. This is a very uncommon progression -- so uncommon that a lot of people would, I am sure, consider it to be a regression. But, perhaps, we now have an opportunity to see this slowness with different eyes.

In a previous post, I wrote, of Shadow of the Erdtree:

There’s a lot of good level design to be found here among the dungeons, castles, and forts, yet the abundance and enormity of it all seems to have deprived the game of significant contrasts, and those special spatial moments, which I found much easier to locate and reflect upon with, say, Dark Souls or Bloodborne. Sure, the sky-piercing spiral of Enir-Ilim is a sight to behold; but soon enough the sequences of grand staircase upon grand staircase, great bridge upon great bridge, creates a perpetual climatic grandiosity that diminishes the very effect of a climax.

This "climax fatigue" is similarly applicable to Elden Ring's weapons, a good number of which have some dramatic, slick, or acrobatically superhuman secondary function. Whereas Dark Souls has almost no obviously "cool" weapons, most being within a range of utilitarian swords, maces, clubs, and spears, Elden Ring has so many superlative offensive items and skills that, after a while, these flourishes become lost among a fantastical morass of melodramatic aesthetics. And whereas Demon's Souls is undeniably much simpler when compared to Elden Ring, there is something satisfying about the older, "inelegant" design where you can feel the proximity to the dungeon crawler sensibility: blunt, rough, and chunky.

The recently unveiled Nightreign would appear to represent one kind of developmental compartmentalization at FromSoftware between more frequently released offshoots and principle works with longer developmental cycles. I'm curious if it might not also represent a forthcoming differentiation between the faster, more spectacular type of gameplay and a slower, less flashy type of gameplay which may be calling back to Miyazaki after years of an intensifying emphasis on the big and bold "anime" side of things.

29 notes

·

View notes

Note

i love how hornsent (npc) is unnamed and how it seems that in hornsent culture names are maybe are only for those of high rank (elder inquisitor jori is the only named hornsent, hornsent calls his family "mother, wife, and child" and refers to leda as "the woman" despite leda clearly having introduced herself to her other comrades and also announcing her name before the enir-ilim battle, but calls marika and miquella by their names, then calls messmer just "the impaler" before clarifying his name) and how it makes you address your ability to have compassion for someone who doesnt like you and doesnt want to be your friend and doesnt give his name. but also its so difficult to talk about hornsent (npc) and hornsent (people) because of this. do we call him the hornsent man??? do we keep going hornsent (npc) forever. to be clear i dont want to him to have a name but its so awkward..

yeah I think it’s super intentional that Hornsent doesn’t have a name; I don’t think it’s because that’s a part of hornsent culture tho because we do have a few other named hornsent of varying roles in society… in addition to Jori there’s also Curseblades Labirith and Meera, Divine Bird Warrior Ornis, and we don’t know if Romina and Midra are themselves hornsent but they’re at least culturally aligned with the hornsent… the Curseblades were not well regarded in hornsent society at all, and were in fact imprisoned before the time of Messmer’s invasion… so I do think that all hornsent did have names in the past, and the reason we don’t know a lot of them is more for thematic reasons

in one way I can see the lack of named hornsent as a testament to how thoroughly they’ve been decimated and erased from history, but I think even more importantly, we have to remember our character is grace-given, so living people like Hornsent and Hornsent Grandam have every reason to be suspicious of us and withhold their names! both respond to us in a very guarded and standoffish way, with good reason!

I also really like the idea that Hornsent no longer uses names from his past because his old self “died” in the fires alongside his family (@katyspersonal puts it really well in this post), like he’s making a choice to be nameless because he can never be that same person again! (also re: Leda I think he just didn’t care enough about her to use her name LOL)

but I 100% agree on the idea that the hornsent NPCs not having names is like, addressing your compassion as the player… these guys aren’t soft, weepy victims who are looking to be your friend… they’re angry, they’re hurting, and they want nothing to do with you! and why should they? their entire world was destroyed! I really dislike the attitude that if you’re not the “right” kind of victim, you clearly deserved everything you got. which is unfortunately how a lot of people have responded to the DLC

with all that said you’re so right that Hornsent just being called “Hornsent” is really confusing lol… I made a post somewhat recently about Hornsent not being able to heal (using the flasks of crimson tears) and like half the replies thought I was talking about ALL hornsent enemies healing lmaoooo it really is a problem… I try to differentiate by exclusively using capital-H Hornsent for our guy and lowercase-h for the hornsent as a whole because that’s how it is in game but it’s still not super distinct. oh well I guess I’ll have to keep typing Hornsent (guy)

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

what i like about elden ring is sometimes when you connect the scattered dots, even if you can’t get a full story, the emotions it evokes could still punch you it the guts

540 notes

·

View notes

Text

someone said that Messmer is hot only in fanart and he actually "looks like weird dried squid in game". well guess what, buddy, THIS is what we call hot in soulsborne fandom.

631 notes

·

View notes

Text

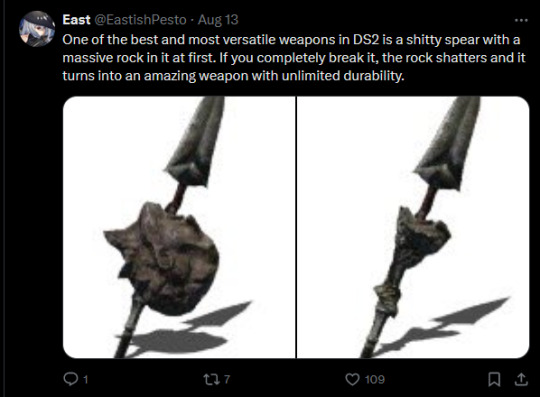

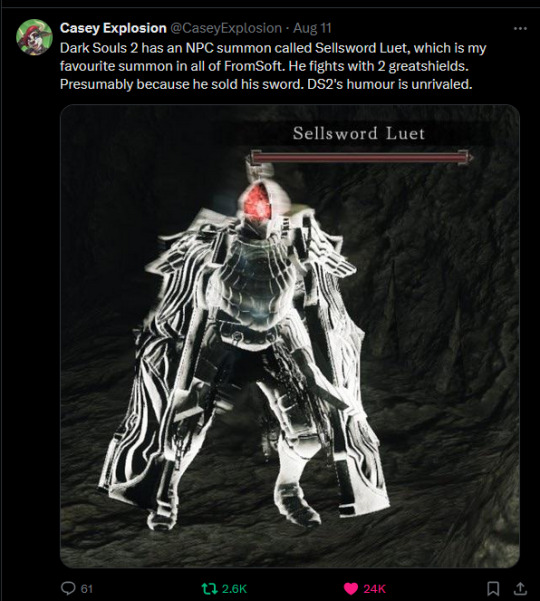

Twitter has had a days long discussion about things they like about dark souls 2 stemming from this post so here's some highlights

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

"Given the very, very small number of lines Igon has in Elden Ring, Lintern expected his recording session, taking place at a studio in Central London, to be short, maybe 40 minutes. It was not. He recalls being in the booth for maybe five or six hours, and that he had to return a week later to a follow-up session. “It was epic in there.”

“I would perform one of the lines,” he recalls. “And then there would be a quite extensive conversation between Mr. Miyazaki and various other people around him in the room. Largely, I think the way things worked was, one of the other people would then speak to Adam, and explain what direction Mr. Miyazaki wanted to move in. But he, the mysterious figure in the center of the room, was very much in control of the entire operation.

“I remember thinking when I left, A, I'm exhausted. That's never happened to me before. I'm absolutely, my voice is wrecked and I'm physically exhausted, and I'm emotionally exhausted as well. B, that was quite an experience. There were a lot of people in there…We were doing lines hundreds of times, literally hundreds, because if I was there for five hours, the actual total amount of lines that I spoke, I could've done in seven minutes.”

For Lintern, Elden Ring was an “eye-opening” experience, one that’s led him to appreciate the emotional possibilities offered by video game stories. But even though he went through a wide gamut of different types of expression, he notes that never once was he asked to bring his emotional levels back down, or temper or mute them in any way. He says every single note he received in that five hours was along the lines of “Do you have more? Can you explode?”

“I'm standing there with my arms outstretched,” he recalls. “And I think at the time, I don't think I even knew that Bayle was a dragon. I think I might've thought Bayle was a person. Anyway, I can't remember, but I'm giving it as much as I possibly can, vocally, emotionally, neck stretching, vocal cords ripping, everything. And then we would come back, and then there'd be silence again, during which I'd have a glass of water. And then we'd come and do it again with a tinge of sorrow, or with a tinge more rage, or slower, or faster, or whatever it happened to be.

“The attention to detail that was given to the character and the performance was pretty much greater than anything I've experienced before,” he adds. “Comparable with characters in Shakespeare that I've played and stuff. People were taking it extremely seriously.”

190 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kids these days don't remember what a fuckimg headache these bitches were

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Miquella's Golden Epitaph just looks like Ostrava's Rune Sword from Demon's Souls...

(The Miquella Art belongs to @fooly_8 from Twitter and the Godwyn Drawing is by @momijigari from Tumblr...)

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

me: *watching a demon's souls playthrough* nobody, absolutely nobody: me: oooo the healing items are dandelions because they were medicinal herbs used in 10th century europe and named after the lunar phases because dandelion flowers represent the sun and the moon and

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

thousands of soulsfans inexplicably angry at great hero ahead wholesome chungus general radahn being incestuously groomed by a catamite despite that exact dynamic having been a core part of dark souls since before i dropped out of college

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maiden Astraea and the Grief of Lost Faith

Many Souls fans liken the Maiden Astraea fight in Demon's Souls to Great Grey Wolf Sif in Dark Souls, describing both as tearjerkers that made them "feel like the bad guy."

The comparison always rubbed me the wrong way—not because it was misplaced or dishonest, but because it was shallow.

It centers how the player feels, and only that. To be fair, this is an understandable response, and definitely an overt part of the text. Against both Astraea and Sif, the player's success in combat, which has thus far been their primary means of progress, is now being scrutinized in a way that casts them unfavorably. They're being forced to reckon with the personhood of the enemy, with their enemy's good intentions and noble virtues.

Suddenly the assumption underpinning most video games—that your actions are good because they're yours—is overturned, and the mechanical rewards for combat are now complicated by emotional punishment. You're fighting a good person, and so you, the player, might just be a bad person.

This is very much in tune with the video gaming zeitgeist of the early 2010s. Dark Souls released just a year before Spec Ops: The Line, which does this same trick on an enormous scale, to well-deserved critical success. Players are placed in the mind of a paranoid American soldier in the Middle-East, and slowly slip into moral depravity as they go from "fighting terrorists" to "suppressing insurgents" to dropping white phosphorous on a refugee camp.

"Are we the baddies?" was really quite a novel idea at the time. It was novel enough that it could be the driving thesis of an entire game.

Perhaps this is why it still stands as the prevailing sentiment around Maiden Astraea—especially when Great Grey Wolf Sif, whose boss fight falls pretty squarely in line with the trend, is such an immediate point of comparison.

But the fight with Maiden Astraea and Garl Vinland is saying something more than that, I feel. The comparison to Sif is what crystallized this vague feeling into a clear, certain thesis for me. It's not just that the player is set against someone "good" or "noble" in Astraea, in the way that Sif is a good dog.

Astraea sets the player against someone human, who is experiencing the height of human loss: the loss of faith.

On some level, all of Demon's Souls is about our human yearning for the sublime, be it supernal or infernal, and the horrible failure that comes when we reach too far.

King Allant reaches for sublime power. In so doing, he achieves a new perspective that shatters his previous understanding of the world—including the values of feudalism and nationalism that drove him to seek power in the first place.

Sage Freke reaches for sublime truth. He believes that with knowledge that is normally forbidden to mortals, he can achieve the just and equitable world that is normally denied to mortals. In the end, however, he fails to consider his own mortal limitations, and he succumbs to the influence of the demon souls.

So on and so forth. The pattern is a familiar one. As Arthur Machen says in his supernatural horror story, "The White People," true sin comes in the "attempt to penetrate into another and higher sphere in a forbidden manner." This plays out with many key characters of Demon's Souls, each one exploring this cardinal sin from a new angle.

Saint Astraea does this too, yet she does it from an angle that I, as a former Catholic, find uniquely sympathetic. It begins when she reaches out for God, and catches only empty air.

"Dear Lord, you are too cruel... You have abandoned us. Is that not punishment enough?"

It's never stated what exactly causes this realization in Astraea—that the God of her world is a distant watchmaker at best, a cruel absent parent at worst. It could have been a direct revelation, such as King Allant received from the Old One, but this doesn't seem likely.

From what the text offers us, I think that Astraea's faith was broken by the Valley of the Defilement itself.

We hear from Biorr that King Allant "fought vigilantly against the vile and depraved," and we see through Yuria's torture that these labels were used for people on the fringes of society, to justify their persecution. Surely this extends also to the "lost and ill-fortuned souls" who were driven to the Valley of Defilement. The land was presumably called the "Valley of Defilement" well before the demon scourge broke out, and so it's the inhabitants themselves—the poor, the diseased, the unwanted—who are the "defilement." Them, and the rubbish and waste that are disposed of there.

The fact that we see aborted fetuses at various points throughout the Valley, mingled with the muck and the refuse and the remains of animals, speaks to the dire state of living there. As the filthy beggar woman says, it's "all the rot of the world, living or not," and it leaves no room for sanity or dignity.

Whatever can be said of the exact circumstances that produced this, or of the land itself, the fact remains that the misery of the Valley's inhabitants is of decidedly human origin.

Bear this in mind when you consider that the Church of Demon's Souls sends missionaries there—as if the Valley folk were suffering from some natural calamity, and not from the malice of the ruling class.

Perhaps that's all the Church could do. After all, the real-life Catholic Church has always been a powerful political entity, but never have they been able to erase poverty or prejudice, or directly stop a monarch from doing something. The same must apply to the definitely-not-Catholic Church of this fictional world, which is pretty committed to realism in that regard.

But even so, it should come as no surprise that every missionary who entered the Valley of Defilement was killed, either by the people or by the land itself.

These missionaries come from the very society that drove the Valley's inhabitants to such inhumane lows. How would they, who live in relative comfort, know how to navigate this treacherous hellhole? And why would anyone accept charity from the hand that beats them down?

So when Saint Astraea enters the Valley of Defilement, full of genuine compassion and goodwill, what does she see?

She sees the sheer magnitude of human suffering, the depth of the squalor, the inhumanity that it represents... and no relief from anywhere. Not from the Church she serves, and not from God on high. Not even in this end-of-days scenario, when demons walk the earth and miracles are witnessed again, does God's supposed mercy reach the Valley.

Saint Urbain might be a deluded, bigoted fool, but he might not be entirely wrong when he calls the people of the Valley "those left behind by God." Perhaps all of mankind has been left behind, and only in the Valley of Defilement is that truth laid bare.

What can anyone do in the face of such a horrible truth?

If you don't run away from them, how do you answer people who are suffering and dying on this scale? If they need miracles, and God does not provide, what do you do?

These questions don't pertain solely to the fiction of Demon's Souls. These are questions that have echoed across human history, philosophy, theology, and myth. Reckoning with the impossible scale of human suffering—the inevitability of it, the ubiquity of it, the horrible depths of it—has been the preoccupation of our greatest thinkers for, well, pretty much all of our time on this planet.

Even when some of us arrive at an answer, it's never a wholly satisfactory answer, and it's usually contingent upon an existing framework of values and beliefs. The Pope says one thing, the Dalai Lama says another, so on and so forth, and the greater share of humanity continues to suffer all the while.

As for Astraea's answer, I'll once again quote the prologue to Machen's "The White People":

"[H]oliness works on lines that were natural once; it is an effort to recover the ecstasy that was before the Fall. But sin is an effort to gain the ecstasy and the knowledge that pertain alone to angels, and in making this effort man becomes a demon."

She does this quite literally. She cannot access the power of God, so she accepts a demon's soul, and uses its power to bring relief to the Valley of Defilement.

Because this power is infernal, not supernal, she cannot purify the foul stagnant waters of the swamp, nor can she cure the diseases of the poor. Rather, she gives the Valley's inhabitants an affinity for filth and disease; it becomes their sustenance rather than their bane, their strength rather than their weakness. The natural order is inverted completely.

This is why Astraea is "the most impure demon of all." Her demonic power imitates the divine mercy that she longs for, yet the results couldn't be more different—perhaps, also, because she extends her mercy to those deemed impure themselves. The description of the spell Death Cloud, made from Astraea's demon soul, says as much.

And in a cruel twist of irony, Astraea's damnation does not ease the pain and misery of the Valley's inhabitants. The Archstone before Astraea's boss room reads, "The poor journey to this rotten place to offer their souls [to Astraea] so that they might be freed from their suffering." They might be sustained by the Valley's filth now, but they are still suffering from it.

They find lasting relief only in giving up their souls to feed Astraea's power, thus perpetuating the whole horrible system.

Astraea's wounds bleed perpetually, never closing, never healing. Her blood fills the grotto where she sits as an object of adoration, still performing the functions of a religion that failed her. All she can say, over and over, is that God has abandoned her, abandoned the world—she has no fewer than three separate voice lines saying this.

Notably, though others might call her a witch, she never turns to "witchcraft" in the archetypal sense. Her grief never turns to anger; she never rails against God. She never discards her clerical robes, she never dons a pointed hat, and she never casts curses or spells. She is stuck as Maiden Astraea, Saint Astraea, frozen in a state of loss.

The moment of her trauma, of her loss of faith, is extended into perpetuity. Even the boss music reflects this:

youtube

The melody loops and loops and loops, and any resolution feeds immediately into another loop. It's a textural piece more than anything, but you can't help getting lost in the endless repetition of that simple, incomplete melody.

Astraea's knightly bodyguard, Garl Vinland, also seems to be lost in unending grief. He rests in a pile of corpses, never removing the armor that is the sign of his holy vow. If you kill Astraea before him, he simply stands in shock, unable to move or speak or act. Unable to move on.

Anyway, uhh...

All of this? A wound that never heals, a grief that never ends?

Yeah, that's... that's how it feels to have lost your faith.

That's how I feel, anyway.

As you probably gathered already, this reading of Astraea is informed by my perspective as an ex-Catholic, now agnostic. My own loss of faith was very painful. It spanned the entire length of my adolescence, into young adulthood—as my rational mind was growing, my queerness was rising to the level of conscious feeling, and nearly every support system in my life was failing me.

My parish community was run by hypocritical bullies, and harbored an actual, real, pedophile priest, but still I reached out to God for answers. I looked to theology instead of community, to study and meditation and prayer. I looked for answers to my own suffering, and to the world's suffering. I looked for resolutions to all the insane contradictions. I looked for something to sustain the faith that was being asked of me. Surely God wouldn't abandon me, even if my parents and teachers and peers were all against me.

In the end, it all fell out from under me. I found plenty to admire, but even more to doubt and disdain.

I couldn't stop loving God or Jesus, but now it felt like they were dead at my feet, and that rot and maggots were visibly eating the corpses—and that everyone around me was politely pretending that they weren't.

I remember crying to my mother when my dog died around this time, and she tried to comfort me with talk of heaven, and I was just inconsolable. All I could say, as I cried for this sweet little animal who had loved me, was that I was "scared for the world." That nothing could ever possibly be right, nothing in the whole wide world, if God weren't there. I could no longer imagine a good, just end to any human life or endeavor, because the only end was death.

I've since recovered from that very low point in my life, and grown into a much happier adult. The grief never left me entirely, though.

The loss of my faith is likely the single most impactful event in my life. Because I'm no longer Catholic, I was able to transition, and I was able to find friends and partners who mean everything to me...

...but because I was Catholic, and still feel that small aching hole inside, I've spent the greater part of my life immersed in art, literature, and philosophy that explores the space where God once lived in my heart. I've spent years studying apocalyptic religions and their various underpinnings—political, social, theological, and narratological. I've become a literary critic, and a scholar of Victorian religion. My first published article is about how Elizabeth Gaskell positions the Victorian working class as an "apocalyptic demographic."

My favorite musical is The Hunchback of Notre Dame. My favorite author is Arthur Machen. My favorite video game is Demon's Souls. The grief that I feel for my lost faith is hardly all of me, but it has touched every part of me.

So when people who have never experienced such grief compare Maiden Astraea to the big sad wolf from Dark Souls, I feel a little frustrated. As a character and a symbol, she's so much more than that.

I could go on, and resolve this rambling, messy, emotional essay in some kind of critical statement about Demon's Souls... but I think I'll just leave it at that. I suppose I just wanted other people to understand what I feel, to see what I see, and to know why this video game is special to me.

If you made it this far, thanks for reading. Umbasa.

#Demon's Souls#Maiden Astraea#video game analysis#personal essay#religion#Catholicism#Apostate#ex Catholic#FromSoftware#Dark Souls#Youtube

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh god Messmer is literally Fromsoft’s version of the Onceler. Oh my god no. We’re so fucked if he breaches containment and infects the greater tumblr ecosystem noooo jumps out the window

54 notes

·

View notes