Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Why do you think that this prison scene is significant when compared to other scenes in Avatar? Also, is it mentioned in the show that there are separate ethnic groups, as opposed to nationalities?

Avatar: The Last Airbender, the Formalist Symbolism of Shot Composition

Link to Video Essay

The series, Avatar: the Last Airbender, remains one of the most critically acclaimed animated shows over a decade after its original debut in 2005. Intricate world-building, an immersive score, and themes of genocide, totalitarianism, Stockholm Syndrome, redemption, and spiritual balance are partially what cultivate and cement ATLA’s memorability to a degree that prompts recognition from outlets such as Vanity Fair, IndieWire, and general audiences years after its premier. It is a heroes’ journey about restoring balance, cross-cultural understanding, and peace after the Fire Nation waged war. However, it is also filled with striking visual storytelling, its awareness of semiotic significance and the delicacy through which it handles visual rhetoric.

While lighting, camera angles, and shot composition are used as formalist signifiers throughout the entire show, I will specifically be focusing on the scene where Zuko visits Iroh in the jail cell. For context, Zuko has been accepted back into the Fire Nation by conforming to their current ideals of ethnocentrism and helping their efforts in the war. Simultaneously, Iroh has been othered and imprisoned for treason because of his rejection of these same ideals. Thus, we know contextually that the two characters are performing and interpreting their racial identities differently. The composition of the scene through its lighting and camera angles, however, adds another layer of commentary to the duality of these two characters. It communicates that while Iroh is physically othered and imprisoned for his enlightened perspective on what it means to perform his racial identity, Zuko is embraced and accepted for his antithetically ignorant perspective on the Fire Nation.

Through its use of light and dark imagery as symbolic concepts within the scene, ATLA demonstrates what Sergei Eisenstein describes as “a cinema that seeks the maximum laconicism in the visual exposition of abstract concepts” in his article, “Beyond the Shot [The Cinematographic Principle and the Ideogram].”[1] The light streaming in from the small window in Iroh’s prison cell represents the concept of enlightenment and awareness while Zuko kneels helplessly in the shadows. This is a subversion of expectations, as Iroh is imprisoned, looked down on, and othered within his nation, yet the light implies he should be treated antithetically. The role reversal between the isolated yet enlightened prisoner and the idolized yet ignorant prince is further emphasized through the stark duality of light and shadow. Eisenstein describes the composition of shots and visual symbolism as a necessary type of collision, writing “What then characterizes montage and, consequently, its embryo, the shot? Collision. Conflict between two neighboring fragments. Conflict. Collision.”[2] Few visual elements mirrored across hundreds of years of symbolic imagery more aptly demonstrate conflict and collision within a shot than the light and the dark—the collision, conflict, and interplay between shadows and the sun that expels them.

Applying the argument for collision within a shot to lighting specifically, Eisenstein states, “The same applies to the theory of lighting. If we think of lighting as the collision between a beam of light and an obstacle, like a stream of water from a fire hose striking an object, or the wind buffeting a figure, this will give us a quite differently conceived use of light from the play of ‘haze’ or ‘spots.’”[3] Through this framing, there is not only the existence of light and shadow within a shot but a battle between them—an apt description considering the broader plot of war between ethnocentrism and cross-cultural unity that permeates Avatar’s world, as well as Zuko and Iroh’s representations of these ideologies respectively. Light and shadow can coexist, yet this coexistence is constantly implicated with the power struggle between the two. Avatar’s shots in the prison scene put light and dark imagery similarly in conflict, further explaining why one must be othered and the other accepted by their nation.

Eisenstein explains, however, that these abstract concepts necessitate an intertextual basis that grounds them in signified meaning. Speaking to how visual signifiers develop culturally understood meanings over time and in relation to the context clues around them, Eisenstein writes that within forms like the Haiku and Tanka, “The method, reduced to a stock combination of images, carves out a dry definition of the concept from the collision between them.”[4] Avatar’s visual rhetoric plays out similar to poetic communication, drawing on the idea that shadows and light, when placed together create meaning. Bolstering the significance of this collision with the shot is a history of cultural ideas and philosophical texts that perpetuate similar associations. Eisenstein recognizes how this type of intertextuality strengthens symbolism, writing, “The same method, expanded into a wealth of recognized semantic combinations, becomes a profusion of figurative effect.”[5] The integration of atramentous and brightened hues into common modern cultural perceptions is seen through how it manifests in language, with common expressions like being in the dark. However the meaning behind the use of shadows is strengthened even further when considering what is perhaps the most famous use of dark and light symbolism across millenia—Plato’s acclaimed allegory of the cave. Plato paints a visual picture of prisoners who live in an underground cave and can only see a wall where the shadows of various objects are projected. Thus, they believe shadows to be reality. Once a prisoner escapes and sees not only the objects that were originally creating the shadows, but also the sun above, he is described as enlightened, having a fuller view of reality.

The shot plays on this symbolism by intentionally depicting Zuko staring down at the shadows of the prion bars while Iroh stares at Zuko directly. This indicates that, much like the prisoners in Plato’s allegory, Zuko is shrouded in ignorance, unable to see how his compliance with ethnocentrism is not inherently necessitated by him being the prince of the Fire Nation. Iroh, on the other hand, sees the real prison bars and from his perspective, Zuko is the one behind those bars, as is emphasized by the camera angles in the scene being shot from inside the cell looking out. Iroh sees a clearer version of reality, understanding a racial performance detached from the Fire Nation’s current culture, and realizing Zuko is mentally imprisoned.

The prison scene is a poignant example of the type of formalism that Eisenstein explores. ATLA’s montage demonstrates “precisely what we do in cinema, juxtaposing representational shots that have, as far as possible, the same meaning, that are neutral in terms of their meaning, in meaningful contexts and series.”[6] The series of shots that comprise this scene strengthens its visual storytelling, as each shot—its perspective and composition—further emphasizes the dichotomy between the two characters within it. Astoundingly, a 3 minute scene has the capacity to communicate the “collision” of othering versus acceptance; cultural enlightenment versus ignorance; and ethnocentrism versus global unity personified between two of the show’s protagonists.

[1] Sergei Eisenstein,“Beyond the Shot,” Film Theory and Criticism, (2009): 15

[2] Eisenstein, “Beyond the Shot,” 19

[3] Eisenstein, “Beyond the Shot,” 21

[4] Eisenstein, “Beyond the Shot,” 15

[5] Eisenstein, “Beyond the Shot,” 15

[6] Eisenstein, “Beyond the Shot,” 15

@theuncannyprofessoro

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why does the poster for The Boys that you chose represent a Banksy piece? Do you think that there is any significance in the fact that street art was chosen as a style to portray this show in summary through the form of a poster? How does this relate to the ideological message that you allude to?

Psychoanalytic Theory in The Boys

In his article titled ”Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Apparatus”, Jean-Louis Baudry concludes that “cinema [appears] as a sort of psychic apparatus of substitution, corresponding to the model defined by the dominant ideology” and that its ultimate and “primarily economic” goal is to prevent any form of deviations or exposure of the dominant ideology as a model.[1] Referencing Freud, Derrida, and even Plato, Baudry dissects and examines the ways in which the cinema works as an ideological tool for the dominant narrative of the culture that produces it, both in its mechanisms and its results. Through this same psychoanalytic lens, I will analyze how the narrative structure and ideological messaging of The Boys others characters through their respective identities while simultaneously upholding and sternly reinforcing the dominant ideology of American society. The Boys, an Amazon Prime original adaptation of the 2006 comic book series of the same name, follows a wide cast of characters; many of which are othered in some way, whether they are a superhero or a normal human being. Therefore, in order to keep this post in scope I will only be discussing one of the main characters, Starlight, examining her othering in the show and the ideological effects it creates.

In order to properly examine how Starlight is othered by the narrative and ideological structure of the show, we must first discuss the ways in which the cinema as a whole is a tool of ideological reproduction. To clarify, when Baudry refers to the term cinema he is discussing the literal structure and composition of a movie theatre, regarding both the presentation of reality in front of the audience and the origin of that reality being projected from behind them. However, I will be referring to cinema as the general idea of an abstract and presented reality—such as The Boys television series—through which all of the same concepts of the representation of the self apply. Baudry argues that “The ‘reality’ mimed by the cinema is first of all that of a ‘self.’ But because the reflected image is not that of the body itself but that of a world already given as meaning, one can distinguish two levels of identification.”[2] The first of these two levels is attached to the image itself, the relation and identification that we feel with the characters presented to us on the screen. While it is not a literal or physical reflection, we can still deeply relate and empathize with them as they go through the trials and tribulations of the story, such as Starlight’s sexual assault and her fight to get justice. And this action, the events, and the problems that the cinema presents us with is the second identification that the reality of cinema mimics. Baudry goes on to argue that what constitutes the images on screen, such as the mise-en-scene or stylization of a work, is of “little importance” as long as the capability of identifying with them is still possible.[3] The question is not one of form or mise-en-scene but one of ideology; of whether or not the camera will permit the subject (the self) to “constitute and seize itself in a particular mode of specular reflection.”[4] As such, cinema becomes an “apparatus destined to obtain a precise ideological effect,” as we inherently relate to and relocate our sense of self in relation to the events that are controlled by the cinema.[5]

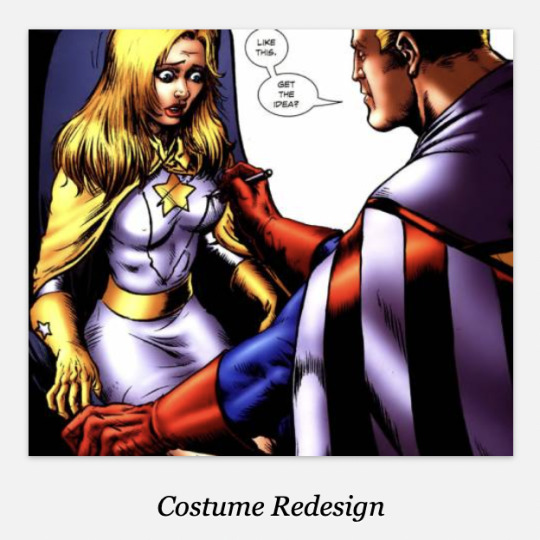

Therefore, despite having lost the literal spatial similarity to Plato’s cave that movie theatres have, television series such as The Boys are no less of an illusion than the movies projected from behind our heads to in front of our eyes. Speculative media is a projection of ideology made into a representative form of reality. What this mechanism produces in the case of The Boys is a carefully articulated reality in which those that are othered, such as Starlight or A-Train or Maeve—characters that we place our idea of self into—are never allowed by the camera to fully seize their (our) hopes for morality or justice, thereby disallowing the viewer to ideologically “constitute and seize itself” in specular reflection.[6] This is particularly true with Starlight’s character arc. Despite being one of the most powerful characters in the show, Starlight is the first in the show to be othered by the structures and dynamics of power in the show. This othering of her gender and sexuality—as well as her ideas of morality and right and wrong—happens on her very first day of work at “Vought”—the international conglomerate responsible for both the creation and management of superheroes—when she is sexually assaulted by her coworker and subsequently reprimanded by her boss for speaking out about the issue. While this is an important event for both her character and the dominant narrative of the show, in the ideological and psychoanalytic sense it is only the beginning of a much larger and more concerning narrative. Throughout the episodes that follow this event, we see an eerily familiar story play out. Her assaulter, The Deep, goes on an apology publicity tour and is suspended for a brief amount of time only to eventually be brought back onto “The Seven” over other, more diverse, and far more qualified superheroes. In spite of her objections to this and to the overall corruption present throughout Vought, Starlight is othered by the rest of “The Seven” and Vought executives for her sexuality, gender, and ideology and is barred from having a say. In the structural narrative of the show, Starlight and characters like her who are othered for various reasons are unable to act, to seize any sense of control over the dominant narrative of the world unless they act immorally. This is evident throughout the show, particularly in the episode after Starlight is assaulted, when she speaks out about the assault and is almost fired, which she only avoids by blackmailing her boss with the threat of loss of profit for Vought.

Although there are flashes and brief instances of morality and humanism in the show, such as Starlight’s relationship with Hughie, another one of the main characters, these moments are few and far between and are becoming increasingly rare as the show is reaching season 4. I would argue that these moments of humanity are small cessions made in spite of the dominant ideology in order to maintain the illusion of self-reflection, allowing the show’s characters to maintain a level of humanity that we can relate to while simultaneously maintaining the dominant narrative that humanism and morality fail to defeat the capitalist powers that be like Vought or Amazon itself.

By delineating the viewer’s self to a character like Starlight—a subject upon which we can reflect ourselves and our desires—and creating an overall narrative that then stifles that sense of self from seizing any form of control or creation of change from the current power structures and ideology of the reflected reality, The Boys is able to effectively portray a speculative reality that has a deceiving duality, hiding it’s ideological message while ostensibly presenting another. The viewer is given a work that allows them to identify with the characters extremely well as they go through hardship and othering while also making those characters incredibly powerful and self-reliant through means of superpowers, such as Starlight. However, this reflection of the powerful and virtuous self that the viewer is presented in the show is at some point, without fail, corrupted or shown to fail when faced against the power structures and dominant, capitalist narrative of the world within the show, ultimately reaffirming and strengthening the dominant, capitalist realist narrative of America and Hollywood.

[1] Baudry, Jean. “Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Apparatus” Narrative, Apparatus, Ideology, 296.

[2] Baudry, Jean. “Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Apparatus” Narrative, Apparatus, Ideology, 295.

[3] Baudry, Jean. “Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Apparatus” Narrative, Apparatus, Ideology, 295.

[4] Baudry, Jean. “Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Apparatus” Narrative, Apparatus, Ideology, 296.

[5] Baudry, Jean. “Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Apparatus” Narrative, Apparatus, Ideology, 295.

[6] Baudry, Jean. “Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Apparatus” Narrative, Apparatus, Ideology, 296.

@theuncannyprofessoro

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why do you think they chose Arabic as a spoken language?

Critical Race Theory in the CW Series: Arrow

Transcript: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1SK4r5rn2i3Dz-4ymnkxqZKCOHO811h-41PcMA-WOxqA/edit?usp=sharing

Arrow (2012-2020) is a CW superhero show surrounding Oliver Queen, a millionaire playboy who gets stranded for 5 years on an island called Lian Yu after a Yacht trip with his father goes wrong. Upon getting rescued by a Chinese fishing boat, Oliver returns home with an agenda. He vows to protect his city as a vigilante, whom the police captain of the series later names “Green Arrow.”

My video essay discusses Critical Race Theory in relation to Arrow. Television, while fictional, is ultimately a reflection of societal values and the show runner’s world view. Critical Race Theory is the concept that the biased perception of race in society impacts the representation accepted in media, which leads to unintentionally distorted depictions of characters of color.

In chapter 5 of Ella Shohat and Robert Stam’s book, Unthinking Eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the Media, Shohat and Stam discuss the diffulcty for the media to properly represent people of color due to their obsession with “realism” in a eurocentric society. This theory is especially reflected in the character Diggle, the only person of color for a while in the eight years that Arrow runs for. Diggle, played by David Ramsey, is introduced in the very first episode as Oliver’s bodyguard, a respected but nevertheless inferior position to our protagonist. In Shohat and Stam’s section “The Racial Politics of Casting,” they point out the recurring theme that “Europans and Euro-Americans have played the dominant role, relegating non-Europans to supporting roles and the status of extras. By episode 3, Diggle displays his abilities, fighting off an assassin from Oliver and his “friend,” Laurel. Throughout this exchange, Diggle gets caught in a headlock, forcing Oliver to come to the rescue and skillfully strike a knife into the hand of the assassin to give Diggle a leg up. Thus, Diggle is placed inferior to Oliver in both employment and physical skill. While some may find this sidekick role is crucial to the superhero narrative, it is also reflective of the level of representation accepted in the media. When looking at other pieces of media, it becomes evident that this relationship of white protagonist and black sidekick is a pattern. Examples of this trope can be found between Captain America and Falcon, and Iron Man and War Machine. Arguably, in both these situations, in the MCU, both Falcon and War Machine are no longer sidekicks - this also eventually becomes true for Diggle, which I’ll discuss later in this post. However, it took years for this to happen and these are only recent developments to their character.

Arrow further displays Eurocentric practices in its depiction of foreigners and foreign countries. “Inscribed within the play of power, language becomes caught up in the cultural hierarchies typical of Eurocentrism. English, especially, has often served as the linguistic vehicle for the projection of Anglo American power, technology, and finance” (Shohat 191). In Arrow, whenever a foreigner shows up, Oliver never has difficulty communicating with them because they all speak English. Even when Oliver is known to be fluent in another language such as Russian or Mandarin, both Oliver and the character(s) he is addressing opts for English. Examples of this can be seen in episode 3, where Oliver immediately assumes that Yao Fei, the skilled Chinese hunter also stranded on Lian Yu, speaks English. Despite Yao Fei answering in mandarin, his immediate understanding of Oliver’s English reflects a Eurocentric presence in the show.

In season 3, the show revolves around Nanda Parbat, a made up land that serves as the headquarters for the League of Assasins, who’s native language is Arabic. The show designs the headquarters with influences of South Asian and Hinduist architecture styels. Nevertheless, the immortal leader of the League of Assasins, Ra’s Al Ghul consistently chooses to speak English, even in private conversation with his daughters Nyssa and Talia Al Ghul. Some may argue that as an immortal being, it makes sense for Ra’s to be fluent in multiple languages such as English. However, Eurocentrism is also present in the wedding scene between Nyssa and Oliver, where the marriage officiant conducted the entire ceremony in English.

Delving deeper into the relationship between language and power in media, Shohat and Stam point out that ““People do not enter simply into language as a master code; they participate in it as socially constituted subjects whose linguistic exchange is shaped by power relations” (193). The correlation between language and power is prevelant in season 1 episode 3. In this episode, Oliver must prove himself to be Bratva, a Russian mob group of this universe, in order to gain the respect of two mechanics representing the Bratva. Oliver asserts his credibility, Oliver begins the conversation in fluent Russian. Upon confirming Oliver’s position as Captain in the Bratva, the two mechanics adapt their speech to suit Oliver’s most comfortable form of communication by speaking in English. This switch in language indicates the switch in power that Shohat and Stam were referencing in their book, as when Oliver wanted something, he appealed to the mechanic’s first language and vice versa.

Arrow, while conforming to Critical Race Theory in many questionable ways, ultimately readjusts its treatment of POC characters by the end of the series. This is done most noteably through the addition of the new Team Arrow, which consists of all POC heroes who, unlike the dynamic between Oliver, Felicity, and Diggle, see each other as equals and dismantle the hierarchy among teammates. This adjustment is still a reflection of Critical Race Theory as the show is aligning itself with society’s push for equal and proper representation of marginalized groups in 2016. 2016 was the year Trump was elected President, exposing a deep divide in America in regards to race, ethnicity, and culture. “The sensitivity around stereotypes and distortions largely arises, then, from the powerlessness of historically marginalized groups to control their own representation” (Shohat 184). Reflecting upon this point, the changing demographics of the Arrow cast in 2016 is reflective of the social scene during this time.

Lastly, as mentioned before, Diggle becomes much more than Oliver’s sidekick by the end of this series. Diggle’s character is most reflective of Critical Race Theory as he goes from being Oliver’s bodyguard to his best friend to his sidekick to his replacement when Oliver goes missing. Each of these identities however, while he becomes a more important and well loved character, is dependent on Oliver’s relationship to him. Furthermore, in Robert Stam and Louise Spence’s work titled “Colonialism, Racism and Representation: An Introduction,” they point out that “We should be equally suspicious of a naive integrationism which simply inserts new heroes and heroines, this time drawn from the ranks of the oppressed, into the old functional roles that were themselves oppressive” (757). Thus, by having Diggle become the Arrow in place of Oliver, Arrow supports the biased fantasy of a black man slipping into the role of a white vigilante without consequence. Nevertheless, by the end of the series, Diggle begins to form his own identity outside of what it is in relation to Oliver. Diggle begins to prioritize his wife and children, and by the last episode, he makes the decision himself to turn down the opportunity to become Green Lantern. This decision is momentous because in the earlier seasons, Diggle wanted more than anything to be a hero and measure up to Oliver’s legacy. By allowing Diggle to choose his own narrative that swerves from audience expectations, Arrow reflects the shift in racial bias and the progress within the television industry, as showrunners are now taking initative to minimize the othering of POC characters. After all, “a film inevitably mirrors its own processes of production as well as larger social processes” (Shohat 187).

Braudy, Leo, and Marshall Cohen. Film theory and criticism: Introductory readings. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Shohat, Ella, and Robert Stam. Unthinking Eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the media. London: Routledge, 1994.

@theuncannyprofessoro

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do you think that casting an Asian actor in a role that is normally played by White actors could be considered progress, when compared to white-washed casting despite the fact that the Asian actor's identity isn't explored?

A Cultural Studies Analysis on Invincible

In my video essay, I looked at Prime Video’s Invincible (2021-) and analyzed the various themes of identity that appear throughout the show, all revolving around the main protagonist of the series, 17-year-old Mark Grayson. I pair this up with various Critical Studies sources that cover reception theory and critical race theory and intersect some of the arguments made to highlight cases of othering within the show. As mentioned, the analysis is centered around Mark’s identity as a superhero, as a young adult, and as a half-Human and half-Viltrumite, as he develops his powers and ‘learns the ropes’ of the superhero job.

In regards to his identity as a superhero, I look at how Mark/Invincible is othered in the scope of superhero media through how his origin story diverts the theme of loss and redemption. Stuart Hall’s reception theory delves into the coding and decoding of messages in certain texts.[1] I pair his argument on how instances of codes can be made to appear as though they haven’t been constructed anymore because of how popular or generally used they’ve become in certain communities with Max Horkheimer’s and Theodor W. Adorno’s argument that in the production of mass culture, more specifically in media, the audience can more or less easily predict the structures and narrative elements of the piece.[2] Superhero media is one of the highest-grossing genres currently across both television and film, meaning that audiences have grown accustomed to the stories of the genre. A result of that is a discourse that mirrors the arguments made by Hall, Horkheimer, and Adorno. Fingers have been pointed specifically at large corporations such as Disney, who mass-produce superheroes in a manner that utilizes the same molds and structures repetitively and has greatly influenced superhero media across the Western production world especially. Attempts at creating unique texts in this genre have been made, resulting in the subgenre of ‘capepunk’, a genre that aims to tell more grounded and realistic superhero worlds and critique mainstream superhero media while making use of adult themes and explicit content. This genre has been popularized in recent years thanks to shows like The Boys (2019-) and Invincible, however, arguments have been made that these types of media eventually end up becoming the media that they’re trying to subvert and critique. I acknowledge that Invincible certainly does appear similar to the media it makes critiques on. It’s not convoluted or unique and fits the descriptions of media that Hall, Horkheimer, and Adorno describe. I do argue that it presents several cases in which it can break off from the mold and create new and refreshing cases that are coded.

The instance I look at in-depth is how Mark continuously faces loss and how this plays into his identity as a superhero. Comparing his journey to a common superhero origin story that is presented in most popular instances of the genre, Mark ticks most of the boxes, but one thing he manages to keep doing is losing. And it ends there. He doesn’t have some kind of redemption or resolution within the episode of the season or the next season, Mark will lose a fight and the episode will end there. We move on to whatever conflict he has to face in the following episode. This is an important aspect of Mark’s origin story, as it not only grounds his story but also reflects his ideology and how it changes. As he physically endures countless beatings and is left unconscious multiple times, his belief in what it means to be a superhero is challenged and broken each time. This repeated loss, however, is interpreted negatively in large circles in online forums who have expressed their annoyance at Invincible’s inability to win fights, or even whether he should be able to call himself ‘Invincible’, causing Mark to be othered from his superhero counterparts across the genre. Mark’s case is seen as unique, in some respects, an early failure in the image of a superhero. I believe this perspective is evidence of being unable to decode the message of the creators on the constant battle that Mark endures in his belief system, which is also symbolized by the title sequence of the show. The “INVINCIBLE” title card is splattered with more blood each episode of the first season, mirroring the repeated damage that Mark endures, while in the second season, the title card is completely covered in blood and begins to crack. The cracks grow in each episode, revealing a new layer underneath.

I bring up how this is made more clear in the second season, more specifically in the mid-finale, and present clips and narration on a case where Mark’s ideology takes a drastic shift. The entire premise of learning to fight with the mentality of killing the opponent creates an opportunity where Mark can go toe to toe with his opponent, yet this ideology conflicts with his identity as a superhero, and this conflict causes him to ultimately lose the fight. This ideology is not only tied into Mark’s identity as a superhero, as additionally, it is also his racial identity. As mentioned in the video, the Viltrumite alien race is coded with the definitions of colonialism, imperialism, and racism that Robert Stam and Louise Spence present.[3] They use their superhuman abilities to kill and conquer different alien races across the galaxy. Mark, the only Viltrumite in the entire galaxy that opposes this idea and seeks to protect his Earth, is othered by other Viltrumites. Interestingly enough, physically and biologically, Mark is a Viltrumite, but they are completely indistinguishable from humans apart from the supernatural abilities they possess and their prolonged life spans. Mark seeks to other himself as much as possible from the Viltrumites. This is symbolized by his superhero outfit that sports a color scheme of yellow, blue, and black and has a unique design, which is completely different from the white and grey uniforms that Viltrumites wear, depicting the uniformity of military garments. Mark’s father, Omni-Man, wears a unique combination of the base of the Viltrumite uniform with a human superhero design on it, symbolizing how he is caught in between these two worlds which is explored more in the second season of the show.

Mark steers away from conforming to Viltrumite ideologies and fights and prepares to save or liberate Earth (and potentially the galaxy) from Viltrumite's influence. I mention how his Asian identity fits the mold of Stam and Spence’s argument on naive integrationism, as the creators substitute an Asian character into a role dominantly played by white characters and never truly explore his Asian identity, however, I argue that Mark’s role as an active opposer of the coded ideologies Viltrumites embody, and therefore doesn’t play Stam and Spence’s argument.[4]

Invincible creates a unique plot in a medium that is saturated with the elements that the show subverts. Mark embodies roles that while othering him from his counterparts both beyond and within the scope of the show, present the case for an unlikely superhero who may be able to surpass those around him. Especially when he’s able to win his first major fight.

[1]Stuart Hall, “Encoding, Decoding,” 551

[2]Max Horkheimer, Theodor W. Adorno, “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception,” 98-99

[3]Robert Stam, Louise Spence, “Colonialism, Racism and Representation: An Introduction,” 753

[4] Stam, Spence, “Colonialism, Racism and Representation: An Introduction,” 757

@theuncannyprofessoro

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

How diverse would you say the casting of True Blood is, considering that it focuses on racism? Does the show only pertain to Black/White relations, or does it involve other ethnic identities as well?

Where is the true racism in True Blood?

While vampires are notoriously known for being sexy outsiders, HBO’s True Blood amps up the sexiness and takes the vampires out of the darkness and into the light of the public eye. True Blood aired in 2008 and is set in the fictional town of Bon Temps, Louisiana. The town resides in a version of the world where vampires “came out of the coffin” two years ago via “The Great Revelation” where they made their existence known to the world. They were able to do so because synthetic blood was created, called True Blood, that allows vampires to get their sustenance from it rather than needing human blood. Although vampires are now allowed to enter mainstream society now, they are not treated as equals. The American Vampire League is a political group that is lobbying to get the Vampire Rights Amendment (VRA) passed that would put an amendment in the constitution, permitting vampires to have the same rights as humans. As interesting as it is, vampire politics are not the main focus of the show and are just embedded in through references, and some TV interviews with the AVL spokesperson, Nan Flanigan. The show actually follows Sookie Stackhouse, a waitress with telepathy, who falls in love with the first vampire she meets, Vampire Bill (underwhelming name, I know), as it is only with vampires that she doesn’t worry about reading their minds. The first season of the show focuses on a murder mystery, as bodies of women who have had sex with vampires –referred to as “fangbangers”, a derogatory term– keep piling up in Bon Temps.

In the show vampires are “othered”, having parallels with Black people and Gay people in America, with the VRA being reminiscent of the Civil Rights Act and the “God Hates Fangs” image in the title sequence being reminiscent of the homophobic Westboro’s church slogan, among other things. While there’s plenty to say about these parallels and critical race theory, what I am going to analyze is the treatment of Black people in the first season of True Blood, in comparison to the new vampire minority group.

First of all, with the shows being set in the south there are mentions of The Civil War being a significant moment of history, but no outright condemnation of it. For some reason there is a trend of making vampires confederate soldiers. The Vampire Diaries did it with Damon Salvatore, Twilight with Jasper Hale, and in True Blood it is the main love interest of Bill Compton. Since Bill is a Vampire who’s been around a bit and was an original resident of Bon Temps, Sookie’s grandma presumes he was a confederate soldier. When it is confirmed, she gets excited and wants Sookie to ask him to speak at a meeting of her Civil War historical group, The Descendants of the Glorious Dead. As the title implies they’re not going to shame Bill for having fought to keep slavery, instead he is an honored speaker at their meeting, where as you can see the confederate flag also makes an appearance

The only stance he makes on his views of the war, was that he and the other soldiers didn’t understand what they were really fighting for or had a choice, which seems a bit revisionist Despite this we are meant to believe that none of the people of the town are explicitly racist towards Black people. Sookie’s grandma’s love of the confederacy isn’t a problem for Sookie’s Black best friend Tara, who sees her as more of a mother figure than her own mother. In fact, when Tara is the only one to actually acknowledge Bill’s role in the war by asking if he owned slaves–which he responds his family did!– she is the one that gets chastised for “spoiling the mood”, while Bill having owned slaves is not confronted.

This leads to a disconnect between the southern setting of the show and its treatment of Black people as all the racism has been displaced onto the Vampire race, who are mostly white. As Sabrina Boyer describes, “In Southern texts by many Southern writers, white characters tend to experience ways of becoming black, which is a recognition of a racist region, as well as a moderately progressive way to comment on racial relations within the South”[1].She argues that True Blood’s use of “white characters that embody blackness” is part of this larger Southern trend that puts racial “otherness” on white characters to confront racism. While, she does acknowledge that this is not unproblematic and makes an argument against it later on. I disagree with the initial progressive analysis of this phenomenon. White characters will never be able to actually embody Blackness and True Blood’s take on this is problematic. The attempt to show racism through “othering” vampires–again the main being a confederate soldier–- panders to white audiences and is a weak hegemonic negotiation. Especially as the show makes no references towards intersectionality with Black vampires who rarely appear. Boyer concludes, “the series, while it] attempts to counter the hegemonic forces surrounding racism in our culture, doesn't critically engage with the fact that people of color, because of their skin or when in the act of passing they are discovered, are immediately othered”[2]. Now, this statement I agree with because True Blood’s displacement of racism onto vampires takes away from actual racism. In doing so True Blood fails its two Black characters by undermining their acknowledgment of racism and putting the oppression of actual minorities below Vampires.

Overall, True Blood takes the metaphor of othering its vampire population too far when its paralleling of oppression of actual minorities takes away from legitimizing racism towards its human population. Despite its Southern setting and call backs towards confederacy, the show does not properly tackle actual racism to justify its use of those images. By not acknowledging the racism of white people towards Black people in favor of vampire othering, the show fails its Black characters and is not as complex as it could be within concepts of intersectionality.

@theuncannyprofessoro

1. Boyer, Sabrina. “‘Thou Shalt Not Crave Thy Neighbor’: ‘True Blood’, Abjection, and Otherness.” Studies in Popular Culture 33, no. 2 (2011): 21–41. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23416382. Pg. 28

2. Ibid. Pg. 36

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

In terms of this issue of gender normativity that you mention, is the entirety of the show's theme aligning with this characterization, or is it isolated to certain parts?

Critical Television Analysis: The Good Place

On the surface, The Good Place is well-loved, hilarious, and surrounds a diverse cast with characters that differ from identity-related stereotypes. The show surrounds Eleanor, who wakes up in heaven, referred to as the “Good Place,” alongside Tahani, Jason, and Chidi (who is labeled her soulmate). Michael is the supposed leader of the “Good Place,” but we later discover that–in alignment with Eleanor’s selfishness–he is actually a devil and this is the “Bad Place.” The characters’ out-of-placeness (except for Tahani and Chidi, who initially think they belong) is meant to be their eternal torture, but Eleanor’s repeated solving of this mystery results in endless reboots and failures. The series ends when the humans team up with Michael and they realize that the entire system is off, as everyone is being sent to the “Bad Place” based on its unattainable, binary measures of morality. They successfully reform the system, resulting in Michael’s transformation into a good being–and living out his fantasy of being a ‘human’ on Earth–and Eleanor, Chidi, and Jason transforming into blissful nothingness while Tahani helps to design a better afterlife.

Photo: Michael and Eleanor.

Although we eventually learn that everyone is being sent to the “Bad Place,” the show’s group of focus is diverse (through their sexuality, gender, or race), generalizing “Bad” people to be those who defy hegemonic norms. This mirrors our current society, especially with those in control being white men (like Michael & the other Devils, and one white female judge) with outdated ideology–I explore this further in my video essay. While the final message of the show recognizes this point system as flawed, revealing the lack of a binary good/badness (the main point of my video essay), it doesn’t at all explore the sexual, gendered, and racial aspects of the characters’ intersectional experiences, making the show more hegemonic than not. I analyze the portrayal of specific characters and how these may be negatively interpreted by viewers despite this show’s positive overall message.

Photo: Tahani, Jason, Eleanor, and Chidi as they stand before the judge and request the chance to 'start' life--and their "Good" vs "Bad" point count--from scratch.

I critique responses to The Good Place that commend its progressiveness based on the fact that its cast is racially diverse and they don’t align with traditional stereotypes, and instead suggest that in this case, “not all representation is good representation” (Hsu, 2021). The show fails to reconstruct intersectional identities in a positively ‘different’ way due to its “color-blind” approach, which disregards, rather than reconstructs, gendered and racialized oppression throughout history. The non-hegemonic aspects of characters’ racial or gender identities are dampened through their adoption of traits that reinforce hegemonic ideology; this is particularly prominent among the female characters, however I address the male characters prior to my conclusion. Primarily, each female character represents an atypical, but similarly problematic form of femininity that continues to reflect the male gaze; Eleanor’s narrative control as a woman is dampened through her alignment with hegemonic masculinity–this is heightened by Chidi’s femininity (perpetuating an innate gender binary), Janet’s non-binary identity is overridden by their similarity to the ideal, domesticated woman (reasserting heteronormativity as the norm), and Tahani’s Pakistani background is misportrayed through her assumption of a privileged white-washed identity (making racial histories invisible) (Kaplan, 2010). Kaplan, Shohat, and Diawari note that the significance of media’s portrayal of gender and race lies in its influence on the minds of its viewers; what media constructs is perpetuated and eventually, realized within our own reality, pointing to the significance of recognizing ideological media as such before its perpetuation. While the presence of three female characters in the show’s main ensemble provide us with the illusion of gender equality, upon closer analysis it is clear that each reinforces problematic stereotypes surrounding race and gender.

Primarily, the protagonist is a white woman–the show opens with a shot of her face, bright and glowing, and follows her perspective throughout the narrative. Eleanor’s non-feminine, general indifference is framed as the essence of her personality, and resultantly, the reason behind her punishment. Kaplan notes that attempts to reconstruct female characters in defiance to gender norms can fail through their consistent creation of a male/female binary; “our culture is deeply committed to clearly demarcated sex differences.” Eleanor illustrates Kaplan’s point that emerging female “representation” remains binarized, as she adopts a specifically masculine position that is characterized by her lack of “traditionally feminine traits,” particularly, her “cold and manipulative” personality (Kaplan, 2010). Flashbacks of Eleanor’s life on Earth revealed that everyone hated her because of her manipulative ways and carelessness surrounding others’ feelings. On Earth, Eleanor used to get drunk before going out with her work colleagues on the night she was designated driver, just to joke that the only place she’d be driving was through the “loophole” she found in the system… When she’s (finally) forced to stay sober and drive, she pretends to be doing it out of care for her friends to get the bartender’s attention, and later chooses going home with him while stranding her drunk friends at the bar. Needless to say, Eleanor isn’t invited to go out with her colleagues again.

This careless emotionlessness is counteracted by Chidi’s “kindness, humaneness, and motherliness,” evident in the fact that his personality surrounds his nervous awkwardness and indecisiveness based on a desire to make the most moral, utilitarian decisions possible (Kaplan, 2010). Many viewers think Chidi illustrates “positive masculinity,” but his emotionality and indecisiveness–alongside a resulting inability to “take action” in the way Eleanor does–suggest he may align with the feminized role as described by Kaplan (Kaplan, 2010). Moreover, Chidi is used to counteract Eleanor’s masculinity and keep the gendered binary “structure intact” despite the supposed stray from hegemonic gender norms (Diawara 2014, Kaplan, 2010).

The idea of Eleanor’s defiance of traditionally feminine gender norms is directly framed as related to her “badness” through her narrative arc, in which her transformation into a “good person” directly aligns with her acceptance of hegemonic femininity; she adopts “kindness, humaneness, and motherliness” and heteronormativity (Kaplan, 2010). When the humans are given the chance to live again and restart their point count, Eleanor struggles; as soon as Chidi kisses her and they recognize their feelings, she finally does better on Earth and becomes “good.” While one could argue the arc’s alignment with heteronormativity is purely coincidental, it contrasts with the show’s previous focus on Eleanor’s bisexuality, aka, its queerbaiting of Eleanor. Throughout early seasons, Eleanor frequently commented on Tahani’s attractiveness, and even came close to kissing Simone (Chidi’s gf at the time); the usage of her bisexuality is, in itself, framed inappropriately comically, and coincides with her previously “masculine” traits– carelessness, moral indifference, and lack of romantic interest in Chidi–suggesting non-heteronormativity to be similarly negative. Moreover, the fact that Eleanor is a woman does not necessarily mean she’s a progressive character, as is evident in her adoption of a non-feminine, but similarly binary form of masculinity, the presence of Chidi as a feminine counterpart , and the show’s aligning of her bisexuality with “badness.”

Photo: Eleanor and Tahani

Janet, a white character, is framed as the perfect woman, which is problematic due to their identification as non-binary, both because it is transphobic and frames servitude (her main purpose) as innately feminine. Primarily, I noticed that Janet mirrors our assignment of femininity to technological sources of servitude: Siri, Alexa, GPS navigation, “the number you have dialed is not in service…” Like these objects, Janet’s “servitude and obedience” are viewed as innately feminine, and are thus assigned a feminine identity (James, 2018). Despite Janet’s attempts to reclaim their lack of alignment with societal labeling norms through the consistent assertion that they are not female, but rather a vessel of knowledge (equating themself to AI), characters always call them a “girl.” Janet never argues with this misgendering, and instead responds with a smile and a kind, “Once again, I’m not a girl” (Beck, 2023). While Janet’s character could have been an opportunity to explore a non-hegemonic perspective, the show harms non-binary identities more than it supports them, by enabling characters to misgender Janet and using their feminine appearance (always fresh, made-up, and in a dress) and feminine subservience to justify this assumption as comically obvious and justifiable (Beck, 2023). The show actually perpetuates their femininity so much that their character is referred to as a girl both within and out of the narrative (among characters and audience members). In the end, Janet is framed as a woman in nature despite their assertion of being non-binary, both aligning femininity with object-ness and servitude and framing non-binary identities as lacking personhood. The show uses Janet as a diversity point without truly questioning binarized views of gender; Janet’s consistent positivity and agreeability disregard the harm of misgendering, and actually works to justify the characters who misgender her by framing Janet’s “femme” physicality and personality as evidence of their ‘obvious’ femininity (Beck, 2023).

Just as Janet’s intersectionality is subdued through their over feminization, the only other intersectional identity (and the only non-white woman) of focus–Tahini–is made palatable through the show’s white-washing of her personality. While Tahani is a first generation Pakistani in the United Kingdom, her struggle-free experience in white-dominated high society disregards a perspective representative of non-white culture, and instead hides it with a British accent and Tahani’s infinite wealth. Tahani’s lack of race-related struggles are completely disregarded through her defining trait: selfishness. Even her greatest deeds, such as organizing charities on Earth, were all based on selfish intentions surrounding her parents’ validation. Her biggest struggle is framed as her sister’s fame, specifically, her parents’ heightened love of her sister, which aligns with Tahani’s inherent self-focused attitude. In this way, UK’s historical colonization of Pakistan and the current othering of British Pakistani are made invisible. (Aljazeera, 2023). As noted by Shohat, attempting to re-frame gendered and racial history (patriarchy and colonialism) is not always done in an “unproblematic” way, just as The good Place’s color-blindness to Tahani’s racial history actually perpetuates social ignorance of historical oppression. In alignment with Shohat’s explanation of the “mark of the plural,” in which any “negative behavior” (Tahani’s personality-defining selfishness) is viewed differently based on the characters’ race, Tahani’s characterization is more likely to be generalized to Pakistani people than Eleanor’s would be to white people (Shohat, 2014). Tahani’s obliviousness to her culture’s oppression projects a falsely generalized idea of this racialized history as insignificant among Pakistani despite its continued prevalence.

While I mainly focus on female identities (complicated by Janet), The Good Place frames the experiences of Jason, and Chidi (in addition to Tahani) as completely unaffected by their race. Jason’s ability to pass as a Taiwanese monk due to him being Asian–despite the fact that he’s from Florida and is not a monk–perpetuates essentialist ideology surrounding sameness based on race, and his heightened lack of intelligence is a poor choice for the only Asian representation throughout the show. Chidi’s violation of hegemonic masculinity (through his emotionality, indecisiveness, etc.) being framed as the reason he resides in the Bad place aligns with problematic characterizations of Black characters “playing by hegemonic rules and losing” (Diawara, 2014). More broadly, the fact that Chidi, Jason, and Tahani are supporting characters for a white woman–like many other characters of color–repaints white-washed film narratives in which POC don’t hesitate to “protect” the “same order that has punished and disciplined” them (Diawara, 2014).

The afterlife’s similarity to Earth suggests its culture as to be reminiscent of our own, however, the color-blind attitude of the main characters disregards the rampant racism that we still work to subdue. Unfortunately, The Good Place’s opportunity to explore an array of perspectives and lived experiences through characters’ diverse backgrounds is lost, even just based on the nature of their show; they do not take into account that the negative representations assigned to each of its characters have a different impact on their community. The fact that a white man created “The Good Place” isn’t surprising, and points to Shohat’s recognition of the necessity for “historically marginalized” groups to “control their own representation” to avoid reproducing something from a white audience’s lens of “pleasure” (Shohat, 2014).

Photo: Tahani and Jason.

Works Cited:

Beck. “‘I’m Not a Girl’: Janet, Nonbinary Representation and ‘The Good Place.’” The Spool. Accessed December 12, 2023.

Diawara, Manthia. "13 Black Spectatorship: Problems of Identification and Resistance." Black American Cinema (2012).

Hsu, Leina, Ruchi Wankhede, Ayan Omar, and Jennifer Ammann. “No, the Good Place’s Jason Mendoza Does Not Defy Asian Stereotypes.” Women’s Republic, March 1, 2021.

James, et al. “The Other Secret Twist: On the Political Philosophy of the Good Place.” Los Angeles Review of Books, October 13, 2018.

Kaplan, E. Ann. "Is the gaze male?." (2010).

Shohat, Ella, and Robert Stam. Unthinking Eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the media. Routledge, 2014.

Staff, Al Jazeera. “Braverman Words on British Pakistani Men Discriminatory: Pakistan.” Al Jazeera, April 5, 2023.

@theuncannyprofessoro #oxyspeculativetv #speculativetvanalysis

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Critical Race Theory in the Dragon Ball Z Namek Saga

While the overall theme of the Namek Saga is that of colonialism and genocide against the Namekian people, episodes 44-48 seemed to possess dialogue and events that most pertains to ideas of critical race theory. While neither the protagonists nor the oppressors are composed of a homogeneous species, the populace of Namek is of a singular species that is being genocided and extorted by Frieza for their dragon balls. Though Frieza’s army is composed of many types of alien species, he practices the imperial methodology of arriving to planets and conquering them with the goal of exploiting the resources and species that exist on the planet.

Although Japan hasn’t been considered to be a part of the Third World, there is a cultural significance of colonialism translated into the show, given that Japan has the history of being both a colonizer and colonized nation. Largely, this section of the show seems to depict a mix of saviorist and anti-colonial ideas. The saviorist aspect of the plot involves the protagonist’s efforts to protect Namek while collecting the dragon balls. There seems to be a greater focus, though, on depicting Frieza’s tyrannical wrath, resembling Third World anti-colonialist filmmaking, having “attempted to counterpose the objectifying discourse of patriarchy and colonialism with a vision of themselves and their reality as seen ‘from within’”(Stam & Spence, 757). Though the show doesn’t make any explicit imitation of a historical imperial power, the actions of Frieza could be potentially compared to either Western colonizers or early 20th-century Imperial Japan. As a result of this alignment, the viewership can look critically at colonialism from the perspective of the oppressed, as the show supersedes and interacts with traditional colonial portrayals.

The first episode that we will be looking at is episode 44. This is the first moment in the Namek Saga where all of the major characters arrive on planet Namek. As a result, the episode more-so lays out the plot as opposed to solely depicting battle scenes or dialogue insignificant to the plotline. Two of the protagonists, Krillin & Gohan, express their first impression of Namek with a comparison between Piccolo's place of residence on earth and the terrain of Namek. This remark is interesting because it is a commentary on the issue of migration and assimilation. Though unrelated to the saga’s dynamic of colonialism and genocide, the mention of Piccolo’s choice to reside in a Namek-like location on earth indicates that the creators of the show are interested in approaching this saga with the topic of othering in the form of species, in this case. It also is an interesting remark because it shows that an explanation of the idea of non-homogenous society to the show’s Japanese audience is necessary, given that Japan is almost entirely homogeneous(Bridges, 779). While a non-Japanese audience might be familiarized with the dynamics of assimilation, Japan’s lack of immigration increases the necessity for the characters to address the Namekian Piccolo’s background as an anomaly.

The cultural significance of Japanese homogeneity is also important in that this saga’s focus on alienism is an approach that breaks a set of strict Japanese communal anchors, such as ethnicity, and culture, in a sense suspending disbelief by disassociating from traditional Japanese ideas or symbols(Bridges, 779). In such a dissociation, it seems now, more convenient for the show to approach a more abrasive concept like race or colonialism, which otherwise would remain a political discussion that only exists from the perspective of homogeneity. Vegeta’s arrival at Namek is another important moment which reiterates the saga’s theme of imperialism. Though Vegeta’s personality had previously been introduced, this moment highlights his newfound rebelliousness against his tyrannical emperor, though his rebelliousness bears no consideration for ethics.

Arguably the center of this saga’s anti colonialist plotline, Frieza and his army are introduced in Namek with a scene of them murdering a Namekian to gain possession of a dragon ball. In literal terms, his use of violence against a less militarily powerful group of people for the purpose of extracting resources bears a close resemblance to colonization or imperialism that has taken place worldwide. This depiction of Frieza aligns with anticolonialist films such as Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, which provides the depiction of “colonialism in Africa as ‘just robbery with violence, aggravated murder on a grand scale’”(Stam & Spence, 755). Though Frieza’s actions aren’t driven strictly by racism, his actions fit a colonial characterization of carrying out mass acts of robbery and murder against a single group of people.

In episode 45, there are several other pieces of dialogue that contribute to the characterization of the Namek saga as being anticolonialist. Firstly, the protagonists encounter two of Frieza’s minions who offhandedly mention their job description of committing genocide. Since science fiction is often regarded as a representation of international politics, it is easy to see how this statement could be compared to an Eichmann style of justifying oppression, where low-level perpetrators see themselves as order followers within a code of imperial conduct(Dyson, 461). In essence, though, it becomes further affirmed that Frieza’s army is meant to be portrayed as an army commiting genocide.

Vegeta’s juxtaposition within the colonial theme is also elaborated in this episode, with his remark that he wants to become a Saiyan emperor of the universe and overthrow Frieza. Vegeta’s case further indicates the shows’ adherence to anti-colonialist filmmaking, aligning with the idea that “In many consciously anticolonialist films, a kind of textual uneven development makes the film politically progressive in some of its codes but regressive in others”(Stam & Spence, 764). To elaborate, rather than depicting all of Frieza's rebels as being benevolent, the distinction is made that these oppressed people are just as capable of expressing selfishness. Mentioning his race explicitly, his motives despite being an “ally” of sorts against Frieza, remain non-egalitarian and racist in his goal of perpetuating Saiyan supremacy.

In episode 47, Frieza’s dialogue introduces the element of language into the saga’s broader colonialist theme: “Speak to us in a language that we can all understand”. This quote from Frieza aligns closely with a characterization of Namekians as being Third World, with his expectation of the Namekians to speak his language on their planet. This remark seems like an imitation of Western depictions of colonialism, where “The languages spoken by Third World peoples are often reduced to an incomprehensible jumble of background murmurs, while major ‘native’ characters are consistently obliged to meet the coloniser on the coloniser’s linguistic turn”(Stam & Spence, 756). Though the show employs Namekian language in such a way, it is done in an anticolonialist fashion where the antagonist of the plot is made to fit this characterization, as opposed to the protagonists.

In episode 48, there is one clear scene that elaborates the saga’s theme of colonialism and imperialism. In this scene, Frieza’s henchmen start slaughtering the village, but Gohan steps in and saves a child, who is the final surviving Namekian in the village. While this scene further justifies Frieza’s comparison to a real-world colonial or imperial force, Gohan’s character employs geopolitical realist ideology that takes oppressed groups into account. To elaborate, this scene aligns closely with ideas of progressive realism that are promoted by many oppressed groups or Third World filmmakers(Stam & Spence, 757). Though the goal of the protagonists is the realist goal of collecting all of the dragon balls before Frieza or Vegeta, it seems that there is a revelation on the part of the protagonists that they must become the protector of the Namekian people, in an effort to combat Frieza’s hegemonic threat. On some level, Gohan’s actions could be interpreted as being saviorist, in the sense that he justifies his own attempted exploitation of Namek’s resources with his efforts to prevent Namekian genocide. At the very least, though, this scene paints Gohan as an ally who considers humanitarian ideals as being fundamental in accomplishing his largely realist and selfish objective.

To summarize the point of this video, it appears that Dragon Ball Z’s Namek saga purposefully attempts to imitate the dynamics of colonialism though Frieza and his army’s genocide of planet Namek. Consequently, other parties in the show such as the protagonists, Vegeta, or the Namekians expand on this dynamic through their responses to Frieza’s actions and speech. By placing an antagonistic imperial power, the show demonstrates an anticolonialist interpretation of history, and allows viewers to experience the issue from the perspective of the oppressed. Given the context of Japanese homogeneity, the alienist focus of the show disassociates its Japanese audience from real-world cultural boundaries, therefore suspending their disbelief further. Gohan and Krillen exhibit their progressive realist ideals, as they interfere in the slaughter of a village and save the last surviving child. The saga’s anticolonialist perspective is thoughtfully, yet prominently shown in these introductory episodes of the saga. Though this plotline isn’t directly translatable to any specific piece of colonial history, it certainly involves a variety of scenes that are comparable to both Western and Third World depictions of colonization.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

How necessary do you think it was for the show to include superpowers in terms of conveying the political or cultural messages?

Superhero Roundtable

Gen V (2023)

The series Gen V is a spin-off of The Boys series on Prime, it aired very recently with the season only wrapping up on November 3rd of this year. The show takes place in the same universe as The Boys and its timeline is meant to align and intersect a bit with the new season. Instead of focusing on the main adult superheros of the universe, Gen V chooses to center its narrative on the younger victims of compound V (Which is the drug people can take to potentially get powers). The show is set in a college that only ‘Supes’ can attend (think Sky High). There they are ranked and all aim for the number one spot and to be a part of the famous ‘7’ supe group. The show is similar to what I talked about in my Buffy roundtable but here demons are swapped with superpowers for adolescent woes metaphors.

How do structural mythology, cultural studies, and cultural history reflect the series?

As the show came out this year it's cultural studies and history is all very recent, and it specifically caters toward Gen Z. In doing so the cast is much more diverse than The Boys and earlier superhero shows. The main character is a young Black woman named Marie who’s love interest is a bigender Korean American who can shapeshift between two different genders of masculine and feminine. The friend group she also meets up with also consists of others diverse in background and ethnicity. The call for more diverse superheroes is definitely a product of more recent cultural values and changes, especially with younger people being the target demographic. The politics of the show also represent the recent political timeline with our generation's disappointment in the actions and lack of actions the government has taken on corruption with capitalism, climate change, etc . This can be seen with Vought International, the multibillion dollar conglomerate that founded the famous 7 and manages ‘supes’. The company also does entertainment, news, weapons, fast food chains etc. The corruption of the company and its supes, most notably its most powerful supe Homelander who’s villain arc mirrors Trump, really fits the current post Trump political climate. The structural mythology of supes in the show is interesting as well. Instead of the show having the classic Hero’s journey with its superheroes and their gaining of powers. The main characters of the show got their powers from their parents injecting them with Compund V so they could profit off of their abilities. The superpowers they have are often the root of their trauma. The main character, Marie, has blood controlling powers that manifested on her first period and led her to accidentally kill her parents in front of her sister. Overall, this pessimistic view of superheroes and their powers is really reflective of our current political and cultural landscape.

In what ways are the superheroes and their abilities informed by their racial, gender, sexual, and cultural identities?

One superhero that exemplifies the concept of their abilities being informed by their identities—specifically gender—is Jordan Li, the bigender Korean American who can shapeshift between two different genders of masculine and feminine that I previously mentioned. Through Jordan Li’s super powers the show is able to mythologize gender fluidity and identity struggles. In this clip, Jordan is talking to their parents who are upset that their developing powers gave them the ability to shift from a boy to a girl. Jordan has to explain that they are still themselves in both forms and have always been the same, but their father still disapproves.

In what ways do costumes and concealing identities further separate the superheroes from normal society? How necessary is it for the superheroes to hide their true identities to successfully achieve their goals?

In the Gen V the superheroes identities aren’t concealed from the public but they do have superhero personas that they are more known by in the public and media sphere. The celebrity-like status they have with their super personas is used to other them and commodify their powers to entertain others as a spectacle. One example of this is with the character Emma whose superpower is her ability to make herself change size. At school she is majoring in becoming a super influencer basically and goes by the persona ‘Little Cricket’ for her popular youtube channel. While her channel is popular we learn that it really is her mother wanting to profit off of her abilities and doesn’t care that she has to throw up and purge in order to change herself. Her power is also fetishized by a male classmate who wants her to get small while they are intimate. So in Gen V the creation of separate identities is not used to achieve their own personal goals but is instead taken advantage of by non-supes to capitalize off of.

How do the economic, political, and social events that occurred during the series’ creation and broadcast cultivate and inform the superheroes’ decisions and actions?

In the series there is a very ‘us vs. them’ mentality between the supes and non-supes that is reminiscent of the current political climate. In episode 7 a senator comes to the school for an interview and it ends in a riot. The senator runs the Federal Bureau of Superhuman Affairs which seeks to monitor and investigate Supes and stop them from harming others. In the panel Senator Neuman is trying to pander to both sides, with boos and applause for each statement as the students are split between wanting to punish Supes like Homelander for killing innocent people or for thinking that not supporting him is Anti-super. As the episode description shows,

Calling all God U #Hometeamers! Today we’re protesting Socialist Victoria Neuman’s town hall on campus! Let’s show Neuman and her Supe-hating woke mob that we won’t put up with their anti-Superhero agenda! THEY WILL NOT CONTROL US! #MakeAmericaSuperAgain #SupeLivesMatter

The supe vs non-supe divide is very politicized with it mirroring liberal and conservative ideals of the spectrum. The situation is very polarizing and the “Supelivesmatter” crowd ends up disrupting the panel and it becomes very violent. The show is not very subtle with its mirroring of Blue Lives Matter and MAGA, especially with Homelander being a stand in for Trump. This is the central conflict between America’s general super population and their actions demonstrating the impact of our own political news cycle on the show.

How do the superheroes question themselves, each other, and their obligations and duties to the people around them?

In the show characters are constantly questioning intentions, who to trust, and what is right and wrong–especially within the supes and non supes dichotomy. The main characters are grappling with if the pain and violence that their powers have inflicted on others unintentionally are actually their fault and dealing with their guilt and self hatred for it at the same time.

This really leads to the central conflict of if their obligations are to use their powers to protect themselves or the non-supes that put them in the position of having these powers in the first place. The show is really complex in its portrayal of this as in the final scene of the show you are really left wondering what is the right thing to do alongside the characters as they decide who they should side with. Gen V is unique because while in The Boys the superheroes are more villainized but in Gen V it’s more unclear as we are able to see through following the adolescent super perspective it wasn't their fault. It is only at university that Marie and other students are able to begin to realize that the violence and trauma their powers have inflicted on their families and other non-supes is not their own but their parents' fault for injecting them with compound V in the first place.

The fact that their parents did in want of fame and fortune promised by Vought International, really shows that capitalism has been the real villain all along.

“Your parents shot you up with a dangerous drսg when you were a baby to make a buck off you. Don't spend a fսcking minute crying over them”

@theuncannyprofessoro

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do you think that the show's heroes are supposed to be relatable?

The Venture Bros.

The Venture Bros. takes many assumptions from the Golden and Silver Age of comics and comments on them. It parodies certain elements of comic book history, including ‘the boy adventurer’ (Jonny Quest) trope and space-age fiction themes and aesthetics. The series follows Dr. Thaddeus “Rusty” Venture, a sad failure of a Super Scientist living in the shadow of his late larger-than-life father, Dr. Jonas Venture. Rusty is a superhero in title but not in practice, yet he still has a rotating cast of villains and sidekicks around him. His arch nemesis is a villain called The Monarch, who I focus on for this piece. I think Rusty represents the more cynical, morally ambiguous Silver age of comics while his father represents the authoritarian Golden age, to put it into Williams’ framework from “(R)Evolution of the Television Superhero”. The Venture Bros contributes to a misanthropic view of superhero narratives. All of the characters have major flaws directly connected to their association with Super Heroism and its flipside, Super Villainy. Changes in values over time are shown in the narrative through flashbacks and convoluted storylines involving many characters over several seasons. Overall, though, the series pokes fun and levies criticism against prevalent superhero notions.

The Monarch, Dr. Venture’s Arch Nemesis, is a scrawny, goateed, middle-aged white male who has made a career out of being evil. In some ways, he is very successful, with an awesome spaceship headquarters, a team of devoted henchmen, and a sexy villainess girlfriend. However, the Monarch is shown to oscillate between overconfident and insecure, as seeking validation, and as unable to thwart his self-proclaimed nemesis, no matter how many opportunities he gets.

The Monarch represents an attitude of dissatisfaction among men who actually have quite a bit going for them. I feel like this reflects a culture of misplaced victimhood held by some men as the liberation of women and other oppressed groups makes them feel like they are losing some kind of power or status.

The Venture Bros. is all about funny costumes and character design. The Monarch has leaned all the way into his butterfly-and-insect-themed villainy. His costume is an integral part of his character, and he is rarely seen without it.

His voice and mannerisms are enough to make the Monarch recognizable even when he is not in costume, but he derives much of his power from his outfit, the consistent theme of his evil operation, and his flashy technology. The Monarch has a hard time performing villainy when not in costume. In this universe, Villany is a career, and the job requires a uniform.

The show is definitely influenced by 9/11 and the entrance of Gen Xers into the media scene. The show debuted in 2003, when the Cold War Kids (not the band) were finally entering the workforce and the public eye and expressing their feelings and attitudes about social and political realities of the time. The Monarch is an expression of social, economic and political disillusionment that can go in divergent directions and lead to extremism. Venture represents apathy and adherence to established systems, despite their idiocy.

In Season 1 Episode 5 of the Venture Bros., the viewer gets a glimpse into the more neighborly side of superheroes and supervillains as they are introduced to members of The Guild of Calamitous Intent when Venture hosts a yard sale at his compound and invites all the Villains he works against, with the understanding that no harm can come to him because it is not guild-approved and therefore the villains have no legs to stand on in terms of evil. Even so, the Monarch, Dr. Venture’s sworn enemy, wreaks non-approved havok at the yard sale. In search of a suitable bathroom, Monarch and Dr. Girlfriend walk through the compound and see the sad emptiness of Dr. Venture’s life. For a moment it seems the Monarch has a realization about his Villainy and almost gives up “Arching” Dr. Venture, but when the security team gives him a fright, the Monarch vows to destroy Dr. Venture and reconstitute the Nemesis status.

I think this faltering of ideology that the Monarch experiences shows how perceived obligations are subject to change situationally. This applies to foreign relations because attitudes about domestic policy, domestic views on other countries, and also relationships between nations and states are products of history but also are fluid.

@theuncannyprofessoro

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

How would you compare this show's use of race to The Black Panther?

Falcon and the Winter Solider (2021)

youtube

"The Falcon and The Winter Soldier" picks up the narrative immediately after the events of "Avengers: Endgame." The series navigates the post-Captain America era, with Sam Wilson (Falcon) grappling with the decision of accepting or rejecting the iconic shield. Simultaneously, a new government-appointed Captain America, John Walker, enters the scene. Against the backdrop of global conspiracies involving the Flag Smashers and the mysterious Power Broker, the storyline weaves together the struggles of identity, legacy, and responsibility. Within this narrative, the series tackles themes of racism, socio-economic disparity, and the quest for justice, elevating it beyond the confines of traditional superhero storytelling.

How do structural mythology, cultural studies, and cultural history reflect the series’ world and world-building around superheroes?

Structurally, the series follows the archetypal hero's journey, exploring the burdens and responsibilities that come with wielding superhuman abilities, particularly in the context of the iconic Captain America shield. This mythological framework serves as a foundation for the characters' development and the overarching narrative.

In terms of cultural studies, the show delves into contemporary societal issues, addressing systemic racism, socio-economic disparities, and displacement. The decision-making around Sam Wilson's acceptance of the Captain America role reflects a nuanced exploration of racial identity and societal expectations, contributing to a broader discourse on representation within the superhero genre.