Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Cultural Appropriation: Chintz in Fashion

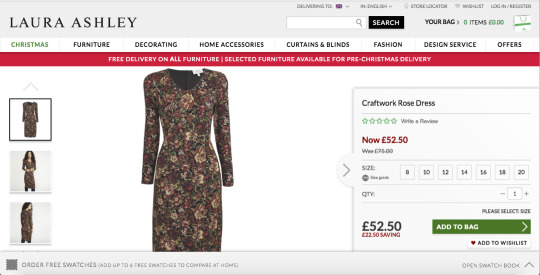

Most people would describe the fabric chintz as a floral pattern that has traditionally been used for upholstery and older styles of clothing, particularly that of the 17th Century. It is one of the most recognisable fabrics in the UK, thanks to inherently British companies such as Laura Ashley, Liberty London and Harrods having used the style in their collections for years.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

However, the material itself isn’t actually British in any way. Nowadays, it’s created from intricate designs that have been printed onto a cotton base, but traditionally, these designs were painstakingly hand painted onto the material by workers and seamstresses in India, using a process known as mordant and resist dyeing. It gradually became popular in British fashion after being imported and eventually, “It was so popular at one time that Western countries banned its import in fear of economic instability in their local textile trades.” (Fotheringham, 2015)

Fig. 4

The brightness of the colours on these fabrics are partly what made them so popular; women of the time had never seen such defined colours matched with the intricacy of design, so it was no surprise that they wanted to buy this new, exotic style instead of their locally sourced clothing. “What was most attractive about Indian chintz was the brilliance and fastness of its colours...When word spread that Queen Mary had decorated a bedroom with calicoes, the use of chintz hangings on walls, floors and furniture became widespread. Later, chintz became highly fashionable for the costumes of both ladies and men.” (Lal, 2015)

Fig. 5

Chintz continues to be popular today, and has become a staple of Britain’s fashion industry, though its roots are hidden about its true origins, raising the question of how much we really know about where our clothing comes from.

Bibliography:

Fotheringham, A. 2015. Guest Post: Renuka Reddy’s Adventures in Chintz. [Blog] The Fabric of India. Available at: http://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/fabric-of-india/guest-post-renuka-reddys-adventures-in-chintz [Accessed 7 Nov 2017]

Lal, S. 2015. Guest Post: Indian Chintz - A Legacy of Luxury. [Blog] The Fabric of India. Available at: http://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/fabric-of-india/guest-post-indian-chintz-a-legacy-of-luxury [Accessed 7 Nov 2017]

Figure list:

Figure 1: Laura Ashley. 2017. Craftwork Rose Dress. [Online] Available at: http://www.lauraashley.com/uk/dresses/craftwork-rose-dress/invt/md917 [Accessed 6 Nov 2017]

Figure 2: Liberty London. 2017. Department: Women’s Clothing. [Online] Available at: http://www.libertylondon.com/uk/department/women/clothing/ [Accessed 6 Nov 2017]

Figure 3: Harrods. 2017. Dolce & Gabbana Floral Peplum Dress. [Online] Available at: https://www.harrods.com/en-gb/dolce-and-gabbana/floral-peplum-dress-p000000000005792173 [Accessed 6 Nov 2017]

Figure 4: Cooper Hewitt. N.A. Textile (India), 1725-50; cotton’ Hx W: 292.1 x 69.9cm (9 ft. 7 in. x 27 1/2 in.); Museum purchase through gift of Julia Hutchins Wolcott and various donors; 1968-79-2. [Online] Available at: https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18467307/ [Accessed 7 Nov 2017]

Figure 5: The Met Museum. N.A. Wentke (Dutch), mid-18th Century; cotton, linen; Purchase from Isabel Shults Fund; 2012

0 notes

Text

Object Review: Debenhams 2005 synthetic fur scarf with polyester lining

This synthetic fur scarf with chocolate brown polyester lining is an object from Modip, the only museum in England based on plastics. It has a slit on the right, designed to be used to wrap the scarf around the wearer. As it’s made with synthetic fur, the price would have been much lower than that of a real fur scarf, suggesting the wearer wouldn’t have been very wealthy, but due to Debenhams being a mid-high range brand, they would most likely have been from the middle class.

The use of synthetic fur brings up the current arguments regarding whether popular fashion houses need to use real fur in their products anymore. Incidentally, in October of this year, the luxury fashion house Gucci announced that they will be removing all fur from their collections starting with their Spring/Summer 2018 collection: “We’ve been talking about it, Alessandro [Michele] and I, for a few months. Technology is now available that means you don’t need to use fur. The alternatives are luxurious. There is just no need.” (Pithers, 2017)

This decision can be linked to Stella McCartney’s influence on fashion. Her strong view on how haute couture doesn’t need to use real fur brought about a debate in the industry that continues even today. “When asked whether she finds it frustrating that the fur ebate is still raging in 2016, McCartney responds: “Yes, extremely. Everyone should be aware of our world we live in. To respect animals and to be aware of nature, to understand that we share this planet with other creatures.”” (Denman, 2016)

Using fur in fashion will always be a relevant debate, although in modern fashion, more and more alternatives are being created using innovative technological techniques which will allow for a more ethical approach to the issue.

Bibliography:

Pithers, E. 2017. Gucci Announces It Will Be Going Fur-Free. [Online] Available at: http://www.vogue.co.uk/gallery/gucci-announces-it-is-going-fur-free. [Accessed 3 November 2017]

Denman, S. 2016. Stella McCartney on fur in fashion: ‘It’s completely barbaric’. [Online] Available at: https://www.thenational.ae/stella-mccartney-on-fur-in-fashion-it-s-completely-barbaric-1.153732. [Accessed 3 November 2017]

0 notes

Text

Object Review: Handmade 1950s synthetic dress with matching satin lined shawl

This sweetheart bust ball gown is made from a synthetic material with boning throughout the bust, giving it structure and definition. The matching shawl is made from the same material and has a silver satin lining.

Corsetry was hugely popular for women during the 19th and 20th Century: “It has often been suggested that working-class women eschewed corsetry altogether, or alternately donned the garments on Sundays and special occasions. This may have been true for some women, however a critical examination of extant material culture and primary source references indicates that many working class women wore corsetry as frequently as middle-class women.” (Summers, 2002).

This garment is assumed to be from the early 1950s, and this can be seen through the boning technique used; the stays are most likely made from baleen, which is “the keratinous material found around the upper jaws of baleen whales, used to filter plankton and krill” (Lynn, 2010). This technique was used around the mid-19th to the early 20th Century, before the use of baleen stays was gradually taken over by the use of steel. The material used was changed to steel because “steel was easily flexible, but far easier to manufacture and use, and considerably less expensive than baleen.” (Holloway-Scott, 2010).

Due to the lack of any labels, it is most likely that this is a handmade garment, probably made for an event by someone who couldn’t afford to buy a new dress, but due to the quality of the stitch work, it can only be assumed that the creator had a talent for this kind of work, perhaps due to a history of creating garments either for themselves or as part of a business. Creating pieces like this was also a very popular trend for the time, so it’s not unusual that this would have been the normal thing to do, rather than reusing an older outfit or piece.

Bibliography:

Summers, L. 2002. Yes, They Did Wear Them: Working-Class women and Corsetry in the Nineteenth Century. Costume, [Online]. Volume 36, Issue 1. Available at: http://www.euppublishing.com/doi/pdfplus/10.1080/cost.2002.0007 [Accessed 4 November 2017]

Lynn, E. 2010. Well-Rounded. [Online] Available at: http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/gallery/2010/11/wellrounded.html [Accessed 29 October 2017]

Holloway-Scott, S. 2010. More About Corsets: Baleen Ho!. [Online] Available at: http://twonerdygirls.blogspot.co.uk/2010/04/more-about-corsets-baleen-ho.html [Accessed 29 October 2017]

0 notes

Text

The History of Dior

In December of 1946, Christian Dior decided to create his own unique fashion house situated in Paris on 30 Avenue Montaigne with The Boussac Group after what he described as “fate” telling him what to do. He bumped into his childhood friend Georges Vigouraux three times consecutively, who had told him of Boussac’s wish to find a designer who could inject new life into his company: “the humdrum shape of a childhood friend… now the director of Gaston, a couture house in the rue Saint Florentin.” (Dior, 1957). In February of 1947, he made history by releasing his first collection, which quickly gained the name “The New Look” and threw Dior into the limelight, something he struggled with initially but grew to accept after creating an alter ego of sorts for his public appearances, as he was a very private, shy man. This collection featured iconic pieces such as the bar jacket and the passe-partout suit, which exhibited his interest in traditional styling methods, such as lining his clothing with taffeta, a technique that had previously been lost due to the restrictions placed upon fashion during the war. Dior’s designs appealed to the side of women of the time that wanted to feel sexy and feminine after such a dark period. His focus on the natural curves of women and how to accentuate these curves celebrated femininity, so much so that his designs were initially seen to be outrageous at the time, although this only made his customers want them more. After an incredible first year for Maison Dior, the fashion house expanded significantly, even after Dior’s shocking death in 1957. The house continues to release new and innovative lines, regularly changing their creative directors to keep the approach fresh and young. Since Dior’s death, they have expanded into markets such as leather goods, jewellery, makeup, shoes, and even have individual watch lines.

References:

Dior, C., 1957. Dior by Dior, 1st ed., N.A, Weidenfield.

0 notes

Text

Balenciaga: Shaping Fashion Exhibition Review

Cristóbal Balenciaga, the mysterious and private Spanish designer born in 1895, was famed for his extraordinary approach to fashion. Full of daring cuts, intricate embellishments and perfectly engineered internal framework, his creations continue to influence and engage with modern day fashion, with current celebrities such as Beyoncé and Kim Kardashian becoming marketing tools for the brand’s clothing.

At the Victoria & Albert museum in London, Balenciaga’s history and origin story is shown through “over 100 pieces crafted by ‘the master’ of couture, his protégées and contemporary fashion designers working in the same innovative tradition.” (https://www.vam.ac.uk/exhibitions/balenciaga-shaping-fashion)

The famous envelope dress was just one of many of Balenciaga’s iconic moments in fashion, each one highlighting his interest in exploring the manipulation of the female figure. Being one of his passions regarding his designs, there were many pieces that showed the creative process behind experimental dresses that appeared to hold their shape almost mid-air, an accomplishment that was amazingly innovative and foreign at the time.

In the upper part of the exhibition, you are taken into a well lit, spacious room, full of glass cases for Balenciaga’s more modern pieces as well as those of his students - a definite contrast to the darkly lit, deep wooden viewing cabinets in the main exhibition which only allowed one point of view.

These cases gave a clear, unfiltered view of the intricacy and care that contributed to the more modern pieces by Balenciaga and his protégées. These pieces were much more daring in their styles and forms, a clear indicator of the development in the confidence and skill that Balenciaga had learnt and passed onto his students.

Oscar de la Renta is one of these famed students, and Balenciaga’s influence is obvious. Here, you can see the delicacy of embroidery on this silk organza over tulle dress, created for the Oscar de la Renta Spring/Summer 2015 New York fashion show. The information card below further highlights this influence: “In the late 1950s, Oscar de la Renta worked briefly as a sketch artist at Balenciaga’s Madrid salon, Eisa. Hr credited this, along with apprenticeships in Paris, for the high standards he later applied to garments for his own New York label. His work is indebted to his Dominican and Spanish roots. As in Balenciaga’s creations, floral patterns and flamenco ruffles are recurring motifs.”

Overall, the Balenciaga exhibition brings attention to the air of mystery that this designer always had about him. His magical creations inspired and amazed those that were lucky enough to see them, and though it gives an insight into how he created them, I personally don’t think anyone can ever truly understand Balenciaga’s complex creativity. Mary Blume summarises this perfectly in her biography The Master of Us All: Balenciaga, by writing “His clothes do not evoke nostalgia because nostalgia is a lightweight emotion, but they do inspire respect, a nearly unknown word in the throwaway world of fashion”.

0 notes

Text

The World of Anna Sui at the Fashion & Textiles Museum, London

Anna Sui is a world renowned American fashion designer, born in Detroit. Known for her expressive colours and distinct textures, she has always been passionate about creating her own looks based on pre-existing garments and trends. From the age of four, she would watch her mother creating pieces and pulling together outfits, thus sparking her dream of becoming a fashion designer and contributing to her incredible success now, having just had a critically acclaimed ready-to-wear Spring 2018 collection at New York Fashion Week.

Throughout the exhibition, the development of Sui’s identity and creative process are clear, shown through the numerous photos and timelines in the corridors between each room. They are often accompanied by photos, videos and narrations by Sui herself of the key events that defined her success. In the introduction room, you’re met with a summary of Sui’s beginnings, narrated by the designer. She talks about her style inspirations and how they were shaped by her introduction to Western culture, as well as the meticulous research she did once she discovered what it would take to become a fashion designer.

The main event of the exhibition was the hall filled with pieces and collections that are the expression of Sui’s aesthetic and passion for what she does. Though there was an obvious experimentation in her technique with colours, fabrics and styles of garments as well as the accessories used to pull the pieces together, Sui’s image and personal style is clear throughout. In a makeshift boutique painted in the glorious ‘Prince purple’, with bright red flooring and black lacquered furniture and accents, the hall brought together everything that represents the iconic designer.

The rest of this exhibition, shown upstairs, was full of the concepts behind pieces and outfits; mood boards, fabric samples and ideas that never made it to the final shows. They encapsulated the sometimes difficult and time consuming process behind runway looks and thus highlighted Sui’s raw talent for grasping and transforming an idea into something that compliments her collections. The exhibition then takes you into a separate, completely white spacious room - a sharp contrast to the grungy, distinctive style of the main exhibition - where you see another timeline. Based on the branding of Sui’s designs, posters and advertising further highlights the way she intends her work to be seen - a fun, ‘free for all’ style. Accompanied by a homemade montage of behind the scenes footage collated by her closest friends at her earliest shows, it gives a sense of The World of Anna Sui.

0 notes