Text

RMCS Practice #18: Loupes!

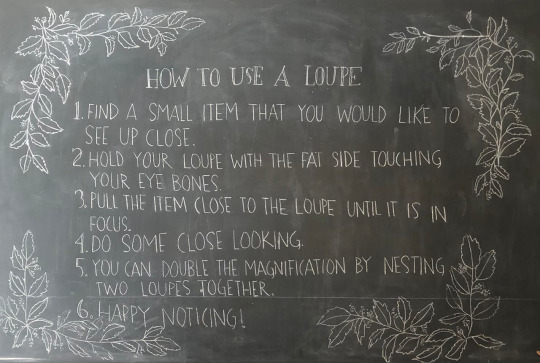

How to Use a Loupe

1. Find a small item that you would like to see up close.

2. Hold your loupe with the fat side touching your eye bones.

3. Pull the item close to the loupe until it is in focus.

4. Do some close looking.

5. You can double the magnification by nesting two loupes together.

6. Happy noticing!

A loupe is a tool to enhance nature study, and nurture the habit of observation. It is a portal into enchanted worlds of moss beds, aphid covered plants, or a drop of water. This magical magnification device makes the world of small large and the invisible visible. It helps children and adults alike shut out the competing visual distractions of the world. We are aided in the scientific method and wonder is multiplied. I like to use my loupe to help me answer these prompts as I engage in nature study: “I notice…”, “I wonder…”, and “It reminds me of… “.

“To pay attention, this is our endless and proper work.”

Mary Oliver

0 notes

Text

RMCS Practice #17: Earthworm farms!

How to Create an Earthworm Farm

Dorothy Childs Hogner writes in the book Earthworms “Boys and girls everywhere are intrigued with the small creatures of the earth. From a very early age they watch with fascination and interest the activities of spiders, insects, bugs, and small wiggly creatures of all kinds, especially earthworms. The story of the earthworms has never been adequately covered. This book presents the earthworm as important, though a small and simple creature. The habits, biological construction, and habitat of the earthworm are described in an interesting way...We often feel that it is hard to believe some things unless we see them happen with our own eyes."

Author Hogner offers the following steps to catch glimpses of earthworms constructing miracles.

You will need the following material:

a pint Mason jar, without cover

a few pieces of broken flower pot

sandy yellow earth, or plain sand, to nearly fill the Mason jar

a few tree leaves or cabbage leaves

1/4 teaspoon of brown sugar

1 teaspoon of coffee grounds

from 2 to 12 garden worms

Place the pieces of broken flower pot on the bottom of the Mason jar, then add the yellow earth or sand. Water, just enough to dampen the earth. Do not let water stand in the bottom of the jar.

Now, put the worms in the jar, and watch. It will take the worms time to start burrowing. Usually they will crawl around and around, trying to poke their way through the glass. (They do not like yellow soil or sand, but this is necessary for the experiment, because of the color.)

Once the worms make up their minds that they cannot escape, they will try to burrow out of sight. Because sand packs hard, you may want to help them start. Make small holes with an ice pick, then watch the worms disappear. Then dampen the leaves and lay them on top of the soil. Sprinkle lightly with brown sugar and coffee grounds. From then until the end of the experiment, that is all you have to do except to keep the sand or soil moist, but not boggy.

0 notes

Text

RMCS Practice #16: Copybooks

1. Find an empty notebook. Plain or fancy but preferably empty.

2. Read anything. ANYTHING! History, Science, Poetry, Biography, Fiction, Nonfiction, Bible, Quran

3. When your heart skips a beat over a sentence or passage because it explains what you've been attempting to articulate, copy it word for word into your journal. When the word choice takes your breath away, copy it word for word into your journal. When you want to remember an idea forever, copy it word for word into your journal. When you are beginning the habit, copy a passage word for word into your copybook.

4. Date your entry and reference the book from which your copywork was chosen.

5. Do this everyday. Start when you are learning to write.

6. In one year, read back through your copywork and enjoy the journey that has instructed your conscience this year.

The copybook or the commonplace book is one of the habits of a Mason education that can begin as soon as a child learns to write. In first grade, it may be a book of favorite lines from A.A. Milne and R.L. Stevenson; in the 3rd-12th grade the habit of the copybook is kept everyday and the child chooses from any of the readings. It is not unusual for a child to ask for the "morning time book" only to go searching and find that another student has retrieved it for their copywork. By the 5th-6th grade, it has become such a habit that teachers are not surprised to end a reading from a book and hear a child whisper, "I want that for my copywork today." For a student that struggles to write narrations, we ask that they choose a passage of copywork from their difficult text. Mason was brilliant in her use of the copybook as a portal into difficult text, beautiful language, grammar, ideas, and the careful molding of a student's ultimate ability to compose their own language. This habit of listening, choosing, and copying is a simple practice that becomes faceted by the keeping of the habit and desire of each student. It nourishes personhood, choice, particularity. This notebook will be as unique as a child's fingerprint.

The keeping of a copybook was not unique to Charlotte Mason; it was a practice utilized in education for hundreds of years. My fourth graders read of the copybook that George Washington kept-- Washington's Rules of Civility;

Just today, I was astonished to read about Isaac Newton's copybook in this article from Maria Popova's endeavor "Brain Pickings:"

When Newton was sent home from college due to plague, he "built bookshelves and made a small study for himself. He opened the nearly blank thousand page commonplace book he had inherited from his step-father and named it his Waste Book. He began filling it with reading notes. These mutated seamlessly into original research. He set himself problems; considered them obsessively; calculated answers, and asked new questions. He pushed past the frontier of knowledge (though he did not know this). The plague year was his transfiguration. Solitary and almost incommunicado, he became the world’s paramount mathematician."

Excuse me. . .I must put this in my copybook!

0 notes

Text

RMCS Practice #15: How to Adopt a Tree

How to Adopt a Tree:

1. Find a wooded spot near your home or school or place of work.

2. Walk around until you find a tree that is just right for you.

3. Spend some time with your tree once a month.

4. Observe your tree closely.

5. You might want to do a bark rubbing or a nature study painting.

6. Touch your tree, smell your tree, hug your tree.

7. You may wish to identify and label your tree.

8. Notice what lives on, in, near your tree.

9. Notice how your tree changes over time.

10. This tree is yours.

Careful observation is built in to many Charlotte Mason methods. She says “scenes must be fully seen to be remembered”. In choosing a tree to adopt, we decide to “fully see” with all of our senses over a period of time. We are developing our habit of observation while entering into an intimate relationship with one tree (this tree becomes our friend). We begin to notice subtle changes that take place across the seasons, and this may translate to recognizing other trees of the same species.

Our loving of “our” tree hopefully helps us begin to love the natural world, develop an ecological literacy, cultivate our innate sense of wonder, and maybe lead us to more sustainable patterns of living?

“If we want children to flourish, to become truly empowered, then let us allow them to love the earth before we ask them to save it.”

David Sobel

0 notes

Text

RMCS Practice #14: Hatching Eggs

For Tumblr:

How to Hatch Duck Eggs:

1. Acquire some duck eggs either through mail order or from a local farm.

2. Plug in your incubator.

3. Using a thermometer/hygrometer to accurately measure, set the incubator to 99-100 degrees fahrenheit.

4. Add water to the troughs to set the humidity to 65%.

5. Place your eggs in the incubator fat side up.

6. The eggs need to be turned 4 times a day (by hand or in an electric turner).

7. On day 23 stop rotating the eggs.

8. Increase the humidity to 75-85%. You can add a wet sponge to help with this!

9. Wait patiently, and listen for peeping inside the egg (the duckling has pipped!).

10. Around day 28 your ducklings should start to hatch!

11. Remove the ducklings from the incubator when they are dry and fluffy!

Charlotte Mason wrote this about nature study: ���We are all meant to be naturalists each in his own degree, and it is inexcusable to live in a world so full of the marvels of plant and animal life and to care for none of these things. “

Our yearly spring practice of hatching some domesticated fowl has helped produce budding naturalists at RMCS. The shared responsibility of tending the incubator, the experience of candling the eggs (“Miracle of miracles, there is a tiny heartbeat in there!”), the vigil of waiting and watching for the ducklings to make their way out of the egg, and the gentle care of these new babies create lovers of the natural world.

This experience never gets old for me. I find this up-close practice of becoming a surrogate mother duck to be incredibly humbling and rewarding. I see many benefits to our children as well. Participating in this process is a useful work (not simply chores but real contributions in the caring of animals). The students are learning about responsibility, lifecycles, and some hard truths about death (sometimes a duckling doesn’t make it). They are closely watching and building the habit of observation when they study: how the duckling makes its way out of the egg, how it finds food and water, how it walks and swims… They are able to feel its downy feathers, see the remnants of an egg tooth that assisted with hatching, hear the nasally peep, and delight in how a duck truly “takes to water”!

From the blastodisc (tiny spot on the yolk) to a peeping duckling, participating in this practice is participating in the renewal of life. Only 16 more days till our new clutch hatches!

0 notes

Text

RMCS Practice #13: Maundy Thursday

For over 40 years I heard the story of the ‘washing of the feet’ from the Bible, but for me, it was as abstract as a fairy tale. Until 2008. In Holy Week of that year I attended All Saints Episcopal’s Maundy Thursday Service. If there is any question about whether or not I knew what the night would hold one only needs to know that I wore tights with my skirt that evening. I had no idea that on that night my faith would become sight in a new, tangible way. When I realized that the priest would be washing feet l i t e r a l l y, I rushed to the restroom and took off my tights, and put my clogs back on without them. That evening I decided that I did not want our school children to think of this story as a fairy tale or symbolic gesture. I wanted them to experience it as a reality, much the way the disciples must have. Washing feet does not have the cultural sense of necessity that it once did, and maybe back then people were used to this kind of thing, but feet, really?

Although each year we gather to wash our students feet it never feels less awkward or weird. But with the reticence comes a holy hush and a sense of reverence for the bodies of the children in our care. I love the moments and the gazes that pass as the child comes forward and allows his foot to enter the water. I love the gentle massaging it with soap and the quiet rinsing. We usually do this out of doors and we are aware of birdsong and new flowers blooming. I love patting the foot dry and smiling at the child to let them know I’m done. I love it when they whisper back,” thank you.”

We don’t force the children to do it, and there is no shame in not wanting your feet washed but it is a practice that I hope we always keep.

One year, as we all sat quietly, waiting for all the classes to be done, Mrs. Deter’s class invited Mandy to the basin and began to wash her feet. Other classes since then have sometimes offered to wash the teacher’s feet after we have washed our classes feet. Each time that happens we remember the first time it happened and there is a sacred blessing on each of us because of what that class first did for Mandy. We recognize that tender quality in a teacher that makes her approachable to her students.

Our work is reciprocal and collaborative, round and whole. There is a lot of love here. And washing eachother’s feet is a hint at the edge of this love.

“Not my feet only, Lord Christ, but all of me.’

1 note

·

View note

Text

RMCS Practice #12: Morning Time

Illustration from “The Princess and The Goblin,” one of our favorite morning time reads!

0 notes

Text

RMCS Practice #11: The Liturgical Calendar

“The liturgical rhythms of the seasons resonate because they illuminate the entire scope of the human experience.” Mary Bea Sullivan

The liturgical calendar is our portal for the habits we hold dearest at our school. The soul rises to meet God, the Psalmist says. Paying attention to and entering the church year has proven over and over to be a gentle, efficient, and simply way of soul care.

Although all of these seasons have a spiritual root we have found them to offer practical benefits as well. Our closing words for Morning Time and Chapel reflect the church year. During Advent we learn new handiwork and say, ‘We wait with hope.” At Christmas we are hearthside for an entire three weeks. We return to school to celebrate the Great Feast of Epiphany and the Service of Lights and say together, “Arise, Shine, your light has come.”

At Lent we say with Mother Theresa, “Love has a hem to her garments that reaches the very dust. It sweeps the stains from the streets and lanes and because it can, it must.’ We wash feet on Maundy Thursday and then return Hearthside for the Great Feast of Easter, staying close to home for Good Friday, Easter and Holy Monday. Then we enter the 50 days of Easter saying together, “He is not here. He is risen,” recognizing all the good gifts we enjoy as a fruit of our hidden life with Christ. We end our year with our St. George Feast which is our Pentecost celebration celebrating victory, new names, gifts and anticipating summer’s harvest.

0 notes

Text

By Mary Oliver

Our Sunday poem this week is by Mary Oliver. At RMCS, we observe the liturgical calendar, so our poem today is in honor of Palm Sunday. 🌿

0 notes

Text

RMCS Practice #10: Schedules

“Grammarphobe” tells us that the phrase ‘in my wheelhouse’ has evolved from meaning a place to store wagon’s in the 19th century to a captain’s domain by the end of the 1800’s to to a hitter’s sweet spot in the 20th century to anyone’s strong suit or chief interest in the 21st century. I heard two of my good friends use this phrase just yesterday in different conversations. One said, “Melanie, let me help you with this Payroll Protection form, this is my wheel-house!” The other said, “Melanie, technology is not my wheelhouse! I’m doing the best I can with zoom/youtube/etc!”

So, in the night I began to think, What is RMCS’s wheelhouse? Silly me, I did not even know of this phrase’s fascinating history. I was picturing Thomas the Train and the Roundhouse, but if you know me, you know I am always confusing my idioms and using the wrong words for things. My grandmother often said she was flustrated, which is a lovely combination of frustrated and flustered. Which might be how we’re all feeling these days. Along with frenetic, frenzied, frantic and fretfull.

Which leads me back to the wheelhouse.

Schedules and habit training often get a bad rap. But in Mason land these two things are portals into all we hope for life to bring our way. In an interview with Marilynne Robinson in 2011 Jason Byasee asks,

“In Gilead you write, ‘I hope you will put yourself in the way of the gift.’ Can you talk about “the way of the gift”?

“I think that we’re given many, many rich means to access greater and greater understanding. Things like music and arts and books and all kinds of things, and experience. And seeking them out is putting oneself in the way of the gift.”

Saint Benedict told us to do the work of the heart throughout the day in the daily prayers (google ‘divine office’ if you want to know more about this), work of the mind in the morning hours and work of the hand in the afternoon. Brother Lawrence taught us that light and life are to be found in every act of presence to the Other in a subject. So, at RMCS we bend our knee to include at least 23 different subjects in a week. Some subjects take up more of our schedule than others and some lessons might only be a 10 minute slot in a day. But when an RMCS student looks back at his week he will find that he has interacted with

Handwriting, maybe calligraphy or Spencerian, poetry, current events, Literature, Sciences, nature study, natural history, art, an artist, a composer, grammar, Latin, the language of our neighbor, local history, state, history, our nation’s history, our neighbor’s history, handicraft, song, music theory through solfege, fable or tale, Shakespeare, Plutarch, the Bible, recitation, mathematics, geometry, computation, citizenship, geography, and so much more.

“Process becomes content,” writes Donavon Graham in Teaching Redemptively, one of our shaping reads. The way one faces the book or thing is equally as significant as the book or thing. RMCS children rarely think of one subject as more interesting than another. They have found that all subjects hold something just for them.

Our middle schoolers recently gathered knowledge they have gained from a variety of subjects, from art to science to natural history to geometry to create phenology wheels. We will include another entry on this practice in time, but today these works stand as a picture of all kinds of knowing rolled (pun intended!) into one.

The schedule is our wheelhouse. Bend into it. Return to it. Trust it.

0 notes

Text

RMCS Practice #9: Chapel

During Assessment Weeks RMCS teachers often ask children to list and describe our chapel practices. In much the same way as 'the garden makes the gardener,' 'Chapel makes the person.' All of ourselves, mind, body, emotions and spirit are invited to chapel. Chapel charms us over and over with the evidence that 'the child is born a person.'

Here are all the parts:

1. Kindergarten rings bells to call the rest of the school to chapel to recall to mind that 'A little Child shall lead them.'

1. Dressing the Table - We include the Christ Candle, a vase of flowers, a statue of The Good Shepherd or St. Francis, the Bible, possibly an art print or some other useful/ beautiful thing and sometimes bread.

2. Opening words include "I was glad when they said unto me, Let us go into the House of the Lord.' or "My house shall be called a house of prayer for all people."

3. Hymns - Some of our favorites include: 'Jesus Christ, the Apple Tree,'

'The Church's One Foundation,' 'Ten Thousand Times Ten Thousand,' 'O Love That Will Not Let Me Go,' 'The King of Love.' During Lent we add 'Stricken, Smitten.' During Advent we add 'O Come O Come Emmanuel' and 'Who Is This?'

4. Prayer of the Ark - This collection is a perennial favorite at our school, a shaping book for sure. I found some helpful information on goodreads and will post it below!

5. Scripture Reading to reflect the Liturgical Calendar. We usually start with the birthday of the earth which is called Rosh Hashanah in the Jewish Tradition. We then follow with more stories selected from the history of the Hebrew people.

At Advent we read the Messianic prophecies.

After Christmas we celebrate the Feast of the Epiphany in a big way and then read stories from the life of Christ. Sometimes we read parables or work through the Lord's Prayer during Lent. In our early days our students wore burlap robes for the lenten weeks but that seemed a little over the top. After Easter we read about the times that the Risen Christ was seen by his followers. St. George Day is a hint at our Pentecost Celebration, thinking about gifts, vocation and the parousia.

6.. Narration of Scripture - Children retell what they heard in the scripture.

7.. Sometimes we have a picture study by Dore' or another artist that reflects the Bible Story:

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/8710/8710-h/8710-h.htm

8. Pass the Peace - In peace times (not during the time of the coronavirus) we touch hands with each other and say, 'peace to you' or 'God's peace to you.'

9. Feel the Minute (read more about this on March 30, 2020's entry.)

10. Bread - Sometimes a class bakes bread or we buy bread and every one gets a small piece. Someone says, 'The Gift of God for the people of God.'

11. We close with a simple song. 'Go now in peace. May the love of God surround you everywhere you go.'

0 notes

Text

The Prayer of the Ark

Helpful information from Goodreads!

Carmen Bernos De Gasztold was one of the five children of a poor family in Arachon, a small town somewhere in France. Her father was a good man but didn't know how to earn enough for his family (like the father in Gabrielle Roy's The Tin Flute). He became unhinged and died when Carmen was only sixteen. During the second world war she worked in a laboratory of a silk factory, helping her mother and her young siblings endure the hunger and countless deprivations brought by the German occupation. It was then, during her free moments, that she began to write her poems.

In 1945 Carmen's mother died. They likewise lost their home at Arachon, and she became a governess of a French family in Lisbon where she became engaged to a man. On the eve of their marriage, unsure of her feelings, she backed out and broke the engagement. Later, she seemed to have found her true vocation, teaching little children. For some reasons, however, she suffered serious physical and mental breakdown. Her siblings were in no position to help her, having troubles of their own. Fortunately, a lifelong family friend, a nun in a monastery, heard about her plight and took her in. There, for many years, the nuns took care of her until she got well. They encouraged her to continue writing and printed her work for local use.

Ms. Rumer Godden was once helping the nuns clean out a cupboard in the convent and there she accidentally discovered Carmen's poems. Captivated by their charm she translated them from their original French to English. "Prayers from the Ark" are what Carmen imagined the animals in Noah's Ark (and Noah himself!) were praying for. These poems brought Carmen renown, becoming a bestseller in Europe. "The Creatures' Choir" likewise have poet animals declaiming, but no longer in supplication. Whereas the animals in the Ark plead, those in the Choir seem to complain or just say whatever it is that's in the minds. All the poems in both books, however, are addressed to God and end with an Amen.

Penguin (the book company, not the animal) first published this one-volume edition in 1976 and has since undergone several reprinting. Let me now give you two examples of the Ark poems--

THE PRAYER OF THE LITTLE BIRD

Dear God,

I don't know how to pray by myself

very well,

but will You please

protect my little nest from wind and rain?

Put a great deal of dew on the flowers,

many seeds in my way.

Make Your blue very high,

Your branches lissom;

let Your kind light stay late in the sky

and set my heart brimming with such music

that I must sing, sing, sing...

Please, Lord.

Amen

THE PRAYER OF THE LARK

I am here! O my God.

I am here, I am here!

You draw me away from earth,

and I climb to You

in a passion of shrilling,

to the dot in heaven

where, for an instant, You crucify me.

When will You keep me forever?

Must You always let me fall

back to the furrow's dip,

a poor bird of clay?

Oh, at least

let my exultant nothingness

soar to the glory of Your mercy,

in the same hope,

until death.

Amen

The cock, dog, goldfish, little pig, little ducks, foal, donkey, bee, monkey, butterfly, giraffe, owl, cricket, cat, glow-worm, mouse, goat, elephant, ox, ant, tortoise, old horse, raven, dove and Noah himself also have their own prayer-poems.

THE OYSTER

Moist, glaucous,

in my mother-of-pearl house,

its door tightly shut

against intruders,

I drink in a dream from the sea:

Oh, let an iridescent pearl--

a milky dawn,

a faerie sheen--

find its tints in the heart of my life.

Then if, slowly,

day by day,

this mysterious seed

grows more perfect,

for my joy

and Your glory,

Lord,

nothing else will matter.

If it must be, I shall die

to let it reach its fullest splendour,

shining--only for You,

Lord--

at the bottom of the sea.

Amen

0 notes

Text

RMCS Practice #8: Feeling a Minute

RMCS students can be loud, busy, even boisterous. We love a big party and have lots of moments that are expansive and rapturous. Our practices are designed to help children hear and affirm their own desire, the voice in their head, their entire, particular, personal tremor.

RMCS is also a place that values silence. Have you found this to be true? Inner stillness is something that is created. There is a kind of silence that feels overly managed, controlled, subservient, even oppressive. This is not a silence we want in our atmosphere and we think that 'Feeling the Minute' has worked miracles in teaching us all how to create silence that is meaningful, fruitful and whole.

A child asks another to 'time him.' He then says, 'Go.' The rest of us keep silence with him, without fidgeting, whispering or communicating with another. We are all simply with ourselves. When the child feels that a minute has passed he says, 'Stop.' The timer then tells him exactly how much time was 'spent.' The goal is to try to feel as close to a minute as possible, in your own bones. After many years it is amazing that the children come within seconds of a minute.

One time a grandfather came to our school and invited us to listen to a Beethoven Symphony with him. He thought that the children would get bored and might only need to listen to a smidgen of it. But we assured him our children could listen to it in its entirety. Which they did. I am convinced that our years of 'feeling the minute' have made us better listeners.

'Silence is the sleep that nourishes wisdom,' wrote Francis Bacon. May we make time for this habit in our days.

0 notes

Text

RMCS Practice #7: Reciting Poetry

Instructions and illustrations from Melissa Shultz-Jones

0 notes

Text

On Sundays we will take a break and get a glimpse into the thought behind Red Mountain community school. #wendellberry

0 notes