Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Tara Donovan

Uses everyday manufactured materials (plastic cups, straws, tape) to create large organic installations.

Transforms synthetic materials into natural, cloud-like or rock-like forms.

Explores accumulation, transformation, and the uncanny beauty of disposable items.

0 notes

Text

Chris Jordan

Creates photographic works documenting mass consumption and waste.

Famous for Midway series, showing birds filled with plastic.

Highlights environmental impact of plastic pollution and human excess.

0 notes

Text

Week 6

The theme this week was re-contextualising objects. I was paired with Rupit, who had short blue wiper snipper cables, while I had a clear sushi tray. At first, we experimented by melting the plastics to see how they interacted, but we discovered they didn’t bond. Instead, we placed the cables inside the tray and heated them, which produced unexpected transformations. The clear plastic became cloudy white, while the blue melted into soft streaks that looked like sky and clouds. Conceptually, it reminded me of the overwhelming presence of plastic in our world, taking on the appearance of a strange new “natural” form. As we continued, the melted mass turned into a blob resembling a rock or lollipop. The dark sticky residue that formed during the process made me think about plastic’s origins in oil, as though it was reverting to its raw state. The whole process felt like a conversation between nature and synthetic permanence.

0 notes

Text

Jessica Stoller

Uses porcelain to create surreal, hyper-detailed sculptures.

Her works often blur the line between beauty and grotesque, organic and artificial.

Themes of femininity, excess, and the body connect to ideas of transformation and enclosure.

0 notes

Text

Recheng Tsang

Works with porcelain, creating delicate and repetitive clay forms.

Their practice often references memory, ritual, and the slow accumulation of time.

The fragility of porcelain connects to ideas of nature, cycles, and organic transformation.

0 notes

Text

Week 5

This week I was away from class, so I worked on the project at home. The theme was the continuum between the organic and geometric/mechanical, with the task of later placing our clay works into a Photoshopped background. Some classmates told me they responded to the weather since it was a stormy, rainy day, but I decided to draw on my own practice and interest in organic forms. Using non-fired clay, I created two spiralling shapes that resemble native New Zealand ferns. Their curled forms feel organic, almost like they are growing or unfurling. I photographed them and later placed the pieces into a digital field setting, enlarging them to look like monumental land sculptures. I liked how they transformed from small studio objects into something that felt powerful and immersive. The process reminded me of how scale and setting can completely shift the meaning of a work.

0 notes

Text

Gordon Matta-Clark is known for his radical interventions in architecture, often cutting into buildings to reveal hidden spaces and question their function. His “building cuts” expose walls, floors, and voids, turning domestic and urban structures into sites of exploration. By removing material rather than adding it, Matta-Clark emphasises absence and presence simultaneously, showing how spaces can confine, contain, or open up possibilities. His work challenges conventional ideas of home and enclosure, revealing that the structures we inhabit are not fixed, they are mutable, layered with both physical and social meaning.

0 notes

Text

Louise Bourgeois Louise Bourgeois often used the home as a symbol of memory, trauma, and psychological experience. Her Cells series, for example, enclosed objects and personal materials within cage-like structures, evoking both protection and confinement. For Bourgeois, architectural forms such as houses, rooms, and enclosures became metaphors for the body and mind—spaces where safety and fear coexist. Her work suggests that the home is never a neutral space but one charged with emotional and often painful histories.

0 notes

Text

Week 4 – Enclosure vs Field

This week we explored the idea of enclosure versus field. My first idea was to make something that resembled a hotel or unit block as a way of reflecting on city living, where homes are becoming smaller and more condensed. Once I began experimenting, the work shifted direction. Instead of a literal building, the piece began to take the form of a floor plan, or even abstract road systems and grids. While different from my original design, I think it still communicates similar ideas—systems of living, movement, and enclosure.

Using metal for this work felt appropriate. Metal is strongly associated with construction, so the material itself connects to ideas of building, housing, and restriction. I imagine a viewer could read this connection and relate it back to the concept of enclosure in urban environments.

Thinking about the home as a symbol of enclosure also led me to Louise Bourgeois. In her practice, the home becomes a recurring metaphor for memory, trauma, and psychological space. Bourgeois often used architectural forms—cells, houses, or cages—as expressions of safety and confinement at the same time. This connection helped me reflect on how structures are never neutral; they hold emotions, histories, and constraints.

0 notes

Text

Giuseppe Penone Giuseppe Penone’s sculptures often reveal presence and absence through processes of carving, imprinting, and erasure. In works where he strips away the outer rings of a tree trunk to expose its younger core, he highlights the absence of what has been lost to time while making the earlier presence of the tree visible again. Similarly, when he presses his hands or body into natural materials, the impression remains as a trace of presence, while the body itself is absent. His work reminds us that absence is not emptiness but a record of something that once existed.

0 notes

Text

Rachel Whiteread Rachel Whiteread often works with casting to make absence visible. By filling the negative space of objects—like the inside of a house, a mattress, or a chair—she creates solid forms that represent what is no longer there. Her work suggests memory and presence through absence, showing how space itself can hold traces of life.

0 notes

Text

Week 3 – Presence and Absence

This week we discussed positive and negative space, and how ideas of absence and presence could be shown using simple materials like blocks of wood, cane, or dowel. In the classroom we began with collaborative prompts, such as making a piece that could fit into someone else’s work, or having one person only add while the other only removed.

For my own experiment, I drilled holes into a flat piece of wood and inserted cane sticks of different lengths. The structure reminded me of trees stripped bare, with only their trunks left standing. Thinking about how a second person might respond to this, I made another work that etched the presence of leaves into a separate piece of wood—suggesting the absence of what was missing in the first.

Although I wasn’t especially excited by the outcome, I did find it useful to think about how absence can be expressed visually, not just as emptiness but as something implied. I also used a tool I hadn’t worked with before, which was a good learning experience. This exercise helped me reflect on how presence and absence often rely on each other to create meaning.

0 notes

Text

Kaari Upson: House to Body Shift

Kaari Upson’s work has always circled around the idea of the home and the body, treating them as deeply connected spaces. From her early Larry Project to her later works made from objects salvaged from her childhood home, she explored how memory, trauma, and family histories live inside both architecture and the body. House to Body Shift brings these ideas together, showing how domestic space becomes almost like a second skin- absorbing experiences, emotions, and generational stories.

Her sculptures and installations blur the line between physical structure and psychological state. Walls, furniture, and everyday objects are transformed into something unstable, fragile, and surreal, much like memory itself. There’s a haunting quality in Upson’s work, a sense that the house is never just a neutral backdrop but a container for hidden tensions and desires.

House to Body Shift reminds us that the spaces we inhabit shape us, just as our bodies hold the imprint of the homes and histories we come from.

0 notes

Text

Wim Delvoye’s Cloaca is a series of installations that replicate the human digestive process through mechanical means. These machines are fed food, which then passes through a system of laboratory-like apparatuses that mimic the stomach and intestines. The process concludes with the production of material that looks and smells like human faeces. Since its debut in 2000, Delvoye has created several iterations of Cloaca, each one refining or expanding the technology involved. The work raises provocative questions about the body, waste, consumer culture, and the boundaries between the organic and the mechanical.

0 notes

Text

As a group we discussed the reading, and others suggested some general ideas to get us started in the workshop. As a class we decided to look at the “body” as a cycle. Thinking both about the cycle of life and the cycles that occur within the body, such as digestion in the stomach. We also considered growth and decay, and how textures of hair, nails, and skin might be translated into material form.

My first idea was to soak cardboard and repeatedly walk across it, pressing my body into the softened surface until it collapsed into mush. For me, this would have represented the endless act of living: walking, moving, performing, until the body inevitably breaks down. However, given the short timeframe, this process was impractical.

Instead, I worked directly with plywood using chisels. I repeated the act of carving into the surface, scratching marks over and over, then collected the resulting wood dust and chips onto cardboard. The fragments resembled residues of the body - like clipped nails, shed hair, or flakes of dry skin. The chiselling itself felt physical and emotional, an almost aggressive scratching at the wood, evoking frustration, anger, or perhaps another body of an animal like a cat scratching.

As a group we collected all works together to create one body or one cycle.

Through this process, I connected the cycle of making and unmaking to bodily remains, turning simple gestures into an abstract representation of presence, residue, and decay.

0 notes

Text

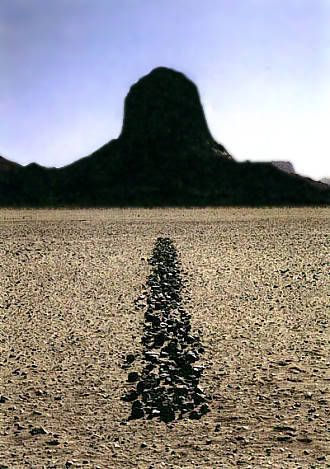

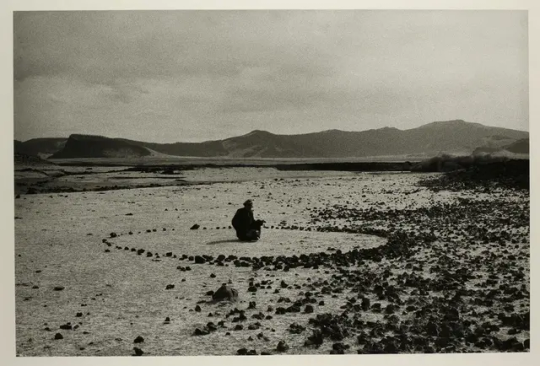

Richard Long

Richard Long is a British land artist known for walking-based works that merge sculpture, minimalism, and nature. He creates interventions in the landscape (such as lines made by walking or arranged stones) and documents them through photographs, maps, and text. Long’s practice emphasises simplicity, process, and presence, using the act of walking as both a sculptural and spiritual gesture. His work does not seek to dominate nature but to mark a quiet human trace within it.

0 notes